CPF Magazine Winter 2020 Issue

A national network of volunteers, parents and stakeholders who value French as an integral part of Canada. CPF Magazine is dedicated to the promotion and creation of French-second-language learning opportunities for young Canadians.

A national network of volunteers, parents and stakeholders who value French as an integral part of Canada. CPF Magazine is dedicated to the promotion and creation of French-second-language learning opportunities for young Canadians.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

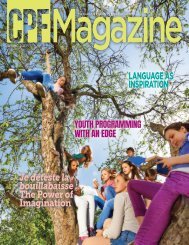

WINTER<strong>2020</strong><br />

<strong>Magazine</strong><br />

$6.95 • FREE FOR MEMBERS<br />

CANADIAN PARENTS FOR FRENCH<br />

HOW TO ACHIEVE<br />

TOTAL IMMERSION<br />

IN FRENCH WITHOUT<br />

LEAVING YOUR HOUSE<br />

Francophone<br />

or Francophile?<br />

PARENTS AS<br />

MULTILINGUAL<br />

EXPERTS

Attention French<br />

Teachers!<br />

Come join our dynamic team today!<br />

Check us out online at www.rcdsb.on.ca or see our current vacancies at<br />

www.applytoeducation.com

<strong>Magazine</strong><br />

CANADIAN PARENTS FOR FRENCH<br />

WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

www.cpf.ca<br />

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE<br />

Michael Tryon, Nicole Thibault,<br />

Towela Okwudire, Denise Massie,<br />

Lucie Newson, Marcos Salaiza<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Catherine Buchanan, Karen Pozniak,<br />

and other authors and organizations,<br />

as noted in their articles.<br />

EDITORIAL MANAGER<br />

Marcos Salaiza<br />

GRAPHIC DESIGN<br />

Stripe Graphics Ltd.<br />

PRINTING<br />

Trico Evolution<br />

SUBMISSIONS<br />

Canadian Parents for French<br />

1104 - 170 Laurier Ave. W.<br />

Ottawa, ON K1P 5V5<br />

(613) 235-1481, www.cpf.ca<br />

Advertising: Cathy Stone<br />

Canadian Parents for French<br />

Email: advertise@cpf.ca<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> is published three times per<br />

year for members of Canadian Parents for<br />

French. Our readership includes parents<br />

of students learning French as a second<br />

language, French language teachers,<br />

school board or district staff, and provincial,<br />

territorial and federal government staff<br />

responsible for official languages education.<br />

CHANGE OF ADDRESS<br />

To signal a change of address,<br />

contact Canadian Parents for French<br />

at (613) 235-1481, or email:<br />

cpf.magazine@cpf.ca<br />

Editorial material contained in this<br />

publication may not be reproduced<br />

without permission.<br />

Publications Mail Agreement No. 40063218<br />

Return undeliverable mail to Canadian<br />

Parents for French at the address above.<br />

To become an online subscriber, email<br />

cpf.magazine@cpf.ca. For an online version<br />

of this issue, visit www.cpf.ca.<br />

WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

FEATURES<br />

3 What Are Immersion Students?<br />

Francophone, Francophile or “In-between”?<br />

7 Parents as Multilingual Experts<br />

10 Celebrating 40 Years of Canadian Parents<br />

for French Saskatchewan<br />

16 5 Ways to Achieve Total Immersion in a<br />

Language Without Leaving Your House<br />

REGULAR ARTICLES<br />

2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE<br />

5 <strong>CPF</strong> TECH & MEDIA<br />

Visit Museums from the Comfort of Home – In French!<br />

6 <strong>CPF</strong> RESEARCH<br />

Summary of the State of FSL Education in Canada<br />

2019 Report – Focus on FSL Programs<br />

12 <strong>CPF</strong> EVENTS<br />

Officially 50! A Conference Marking 50 Years of<br />

Linguistic Duality and Education in Canada<br />

18 <strong>CPF</strong> RESOURCES<br />

My Experience with Encounters with Canada<br />

20 KEY <strong>CPF</strong> CONTACTS ACROSS CANADA<br />

This issue of <strong>CPF</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> is printed<br />

on 70lb Endurance Silk, using vegetable<br />

based inks. The paper is FSC certified by the<br />

Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®), meaning<br />

it comes from well-managed forests and<br />

known sources, ensuring local communities<br />

benefit and sensitive areas are protected.<br />

Canadian Parents for French is a nationwide, research-informed, volunteer organization<br />

that promotes and creates opportunities to learn and use French for all those who<br />

call Canada home.

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE<br />

A<br />

cross the country, we are in the midst<br />

of winter. Many of our regions are<br />

experiencing unusual weather<br />

patterns. Unless we are avid sports enthusiasts,<br />

most of us prefer to cocoon inside our homes<br />

with a favourite beverage and a good book.<br />

May I suggest that you consider enjoying the<br />

latest issue of <strong>CPF</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>? It is full of articles<br />

that will inform you, perhaps have you thinking<br />

a little differently, or taking up a challenge with<br />

respect to FSL education and activities.<br />

Last year was an exciting one for Canadian<br />

Parents for French: <strong>CPF</strong> Saskatchewan celebrated<br />

its 40th anniversary; many of our <strong>CPF</strong> members<br />

were able to attend the Officially 50 Conference,<br />

celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Official<br />

Languages Act; our Branches and Chapters<br />

continued to hold exciting events for students<br />

and their families, they advocated for more<br />

and better programs to serve the needs of<br />

those wanting to learn and use French; a <strong>CPF</strong><br />

Leadership Networking Event was held in<br />

October where we learned about governance<br />

issues that will make us a stronger organization;<br />

the latest report on the State of FSL was<br />

launched at that event, it was wonderful to see<br />

so many people willing and able to share their<br />

experiences with other like-minded individuals.<br />

Whenever I meet <strong>CPF</strong>ers from across the<br />

country, I am struck by their enthusiasm and<br />

willingness to volunteer; attending meetings,<br />

offering programs for students and advocating<br />

on their behalf. I am grateful for the many<br />

hours those volunteers share and spend on<br />

behalf of our organization. If you don’t know<br />

how else you could become involved in more<br />

initiatives, speak to your Branch office or<br />

your local Chapter. They will be happy to<br />

hear from you! n<br />

Nancy McKeraghan,<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> National President<br />

DON’T MISS THE BEST SUMMER<br />

OF YOUR LIFE!<br />

FRENCH IMMERSION SUMMER CAMP<br />

IN QUEBEC CITY<br />

FROM JULY 5 th TO AUGUST 7 th <strong>2020</strong><br />

Université d’Ottawa | University of Ottawa<br />

FRENCH IMMERSION<br />

at uOttawa<br />

► No minimum level of<br />

French required<br />

► French lessons each<br />

morning of the week<br />

► Housing in residence:<br />

single rooms<br />

► Many activities, games,<br />

pedagogical visits and<br />

excursions<br />

► More than 400 students<br />

from all around the world<br />

You are between 14 and<br />

17 years old, have fun with<br />

us this summer learning<br />

French and discovering a<br />

new culture!<br />

A unique opportunity<br />

with unparalleled support!<br />

• French immersion available in 86 undergraduate programs<br />

• Open to core, extended and French immersion students<br />

• Special courses to make the transition to bilingual<br />

university studies<br />

• An extra $1,000 per year for studying bilingually<br />

• An authentic bilingual environment in Canada’s capital<br />

immersion@uOttawa.ca<br />

www.immersion.uOttawa.ca<br />

2 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

CONTACT US:<br />

international@collegegarnier.qc.ca<br />

+1 418 681-0107 ext. 305<br />

garnier-international.com

What Are Immersion Students?<br />

Francophone, Francophile or “In-between”?1<br />

BY CATHERINE ELENA BUCHANAN OLBI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR AND FRENCH LANGUAGE PROFESSOR<br />

In 2017, the Régime d’immersion en<br />

français 2 of the University of Ottawa<br />

celebrated its 10th anniversary,<br />

at which the Official Languages and<br />

Bilingualism Institute (OLBI) organized<br />

a symposium. All stakeholders were<br />

present – professors, researchers,<br />

politicians, administrators and students<br />

– and a roundtable was organized where<br />

four immersion students spoke about the<br />

shaping and reshaping of their linguistic<br />

identity. The discussion touched on the<br />

confusion that often surrounds certain<br />

key concepts linked to the identity of<br />

learners of French as a second language<br />

(FSL), not only for students but also for<br />

their parents.<br />

How does your child self-identify?<br />

Does she see herself as an anglophone<br />

learning French? Does he consider himself<br />

to be a francophone, a francophile, or<br />

perhaps an “in-between”? What about<br />

the perception of others? The good news<br />

is that concepts of identity are everchanging.<br />

Your child will constantly move<br />

between languages and cultures and be<br />

the richer for it. The bad news is that<br />

they may carry strong feelings about this<br />

linguistic branding.<br />

Francophone<br />

When the etymology of the prefix franco<br />

is analyzed, it is clear that it indicates<br />

either French ancestry or the use of<br />

the French language, often in a specific<br />

region. The suffix phone, which comes<br />

from the Greek phôné, means voice or<br />

sound (Le Petit Robert, 2003). Le Petit<br />

Robert, a dictionary from France, defines<br />

a francophone as a person who, in certain<br />

circumstances, usually speaks French as<br />

either a first or second language (Le Petit<br />

Robert, p. 1125, 2006). This would include<br />

all Canadian FSL speakers, regardless of<br />

their school programs. According to the<br />

Multidictionnaire from Quebec, where<br />

language is a major political issue, a<br />

francophone is someone “whose mother<br />

tongue or language of use is French:<br />

there are more than five million<br />

francophones in Quebec” (p. 663, 2003).<br />

This would exclude most FSL learners.<br />

Finally, from a more official perspective,<br />

Statistics Canada (2010) summarizes the<br />

situation well:<br />

There is no established definition<br />

of Francophone. For historical<br />

reasons, Statistics Canada has<br />

generally used the criterion of<br />

mother tongue, that is, the first<br />

language learned at home in<br />

childhood and still understood<br />

at the time of the census.<br />

Accessed August 23, 2018 at<br />

www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/<br />

89-642-x/2010001/article/<br />

section1-eng.htm<br />

Francophile<br />

As a result, FSL learners are sometimes<br />

labeled Francophiles, which also causes<br />

confusion. Le Petit Robert defines a<br />

Francophile as someone who “loves<br />

France and the French, supports French<br />

politics "(p. 1124). The Multidictionnaire<br />

broadens the definition to include the<br />

love of francophones. Some academic<br />

institutions have taken it to include FSL<br />

learners. At the University of Ottawa,<br />

a Francophile is defined as someone<br />

who comes from the English-speaking<br />

community, but enjoys both French<br />

culture and language (Knoerr, 2016, p.50).<br />

This entanglement of francophonefrancophile<br />

affects not only FSL learners,<br />

but also those who teach French. For<br />

example, a Franco-Ontarian professor,<br />

who is an established researcher in the<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 3

field of language policy, tells how her own<br />

identity was shaken when she was told,<br />

in a conference setting:<br />

“Madame, you certainly don't expect<br />

us to consider you francophone.<br />

Francophile, yes, but you<br />

are not francophone.”<br />

In her view, in a franco-dominant<br />

context, I had no right to call<br />

myself francophone. 3<br />

(Lamoureux, 2013, p. 124)<br />

This example demonstrates the<br />

confusion inherent to these terms. The<br />

professor, born and raised in a French<br />

environment, is a true defender of<br />

her community’s rights. Some people,<br />

however, dismiss her roots and identify<br />

her as a francophile since her French is<br />

not “good enough”. What does this mean<br />

to FSL learners?<br />

"In-between"<br />

Immersion students can be defined as<br />

being “in-between” two languages . Roy<br />

(2010) and Lamoureux (2016) see them<br />

as both anglophone and francophone.<br />

However, FSL learners have a hard<br />

time seeing themselves as bilingual; it<br />

seems to be an inaccessible goal. Clearly<br />

they cannot be solely anglophone or<br />

francophone, so they are perceived as<br />

anglophones learning French (Roy, 2010).<br />

They inhabit "an in-between identity to<br />

which are attached cultural values specific<br />

to that space". (Lamoureux, 2016 p.549).<br />

They are at a crossroads.<br />

Identity<br />

These three terms – francophone,<br />

francophile and “in-between” – lead us<br />

to the dual nature of identity. Fortunately<br />

or not, one’s identity is not fixed. It is<br />

formed and reformed along with one’s<br />

environment. Identity is constructed at<br />

school, through encounters with others,<br />

and through learning, collaborating and<br />

playing (Lamoureux & Cotnam, 2012).<br />

This process continues in university and<br />

throughout life. Moreover, the concept<br />

of identity is twofold: however we may<br />

define ourselves, others may define us<br />

differently (Brosseau, 2018).<br />

Language proficiency also affects<br />

immersion learners’ identity (Séror and<br />

Weinberg, 2015). When we speak a second<br />

language, native speakers judge us and<br />

decide whether or not we are legitimate<br />

members of their community, adding to<br />

the complexity of the identity problem.<br />

The round table<br />

At the round table on linguistic identity,<br />

all of the concepts discussed in this article<br />

surfaced repeatedly in the comments of<br />

the four participants. They spoke of their<br />

immersive experiences and how their<br />

identity had evolved through school, work<br />

and social encounters. The question was<br />

put to them: How do you define yourself<br />

linguistically? The overwhelming response<br />

was that they strongly rejected all<br />

labelling. Labels carry connotations, and<br />

even those given with the best intentions<br />

can actually have the adverse effect of<br />

creating distance, or worse, exclusion,<br />

from the French-speaking community.<br />

It appears that the terms francophone<br />

and francophile carry different meanings<br />

depending on who assigns them or<br />

receives them.<br />

All participants mentioned tensions<br />

surrounding their own linguistic identity<br />

and their relationship to French. Through<br />

family and school, they took advantage of<br />

formal and informal learning opportunities<br />

that gave them access to the Frenchspeaking<br />

world. Over time, they gained<br />

self-confidence. Their experience as<br />

immersion students made them aware<br />

that their identity had been transformed<br />

and that they were ready to engage with<br />

francophones. These participants now say<br />

that they consider French as part of their<br />

identity, in an inextricable way, beyond the<br />

labels of francophone or francophile. One<br />

of them said:<br />

[RIF] gave me the confidence and<br />

tenacity to keep trying. I can draw a<br />

very straight although wiggly line from<br />

the immersion program to my job right<br />

now. I had a microcosm of that in<br />

the immersion program or through the<br />

immersion program, and that has had<br />

a big influence on me. I’m now neither<br />

francophone nor anglophone; I am me.<br />

You might ask how I, as a French<br />

professor, would define FSL learners.<br />

My answer is that I don’t really know.<br />

All of these terms are labels; some have<br />

political weight and can ignite fierce<br />

reactions. FSL learners should just be<br />

proud of the fact that they know another<br />

language. It’s a gift.<br />

When we learn a language, we<br />

take on a new identity. We appropriate<br />

its sounds and its culture and learn<br />

something of the values and norms it<br />

conveys. The round table participants<br />

showed how integral French can be to<br />

the identity of FSL learners. Whether<br />

francophone or francophile, it is up<br />

to lovers of the language to adopt all<br />

learners of French and to embrace all<br />

those who identify with its culture.<br />

This is in keeping with the vision of<br />

Tahar Ben Jelloun, a French-language<br />

Moroccan writer, who speaks eloquently<br />

of the richness of knowing multiple<br />

languages:<br />

C'est mieux qu'un simple mélange ;<br />

c'est du métissage, comme deux<br />

tissus, deux couleurs qui composent<br />

une étreinte d'un amour infini.<br />

(It's better than a simple concoction;<br />

it's a blending of two fabrics, two<br />

colours in a embrace of infinite love).<br />

(Le Monde diplomatique,<br />

2003, p. 20). n<br />

To see the complete list<br />

of references, please<br />

visit cpf.ca<br />

1. To read more on the subject: Buchanan, C. E. (2018) (Re)Shaping Identities : The impact of higher education immersion on students’<br />

sense of identity. In Knoerr, H., Weinberg, A. & Buchanan, C. E. Enjeux actuels de l'immersion universitaire / Current <strong>Issue</strong>s in University<br />

Immersion. (153-174). Montréal : Marquis<br />

2. French Immersion Stream<br />

3. « Madame, mais vous ne vous attendez certainement pas à ce qu’on vous considère Francophone. Francophile, oui, mais vous n’êtes<br />

pas Francophone ». À ses yeux, dans un contexte franco-dominant, je n’avais pas le droit de me dire Francophone.<br />

4 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

<strong>CPF</strong> TECH & MEDIA<br />

>in French!<br />

For those winter days when it’s hard to go out or simply when you want to stay cozy<br />

at home, many Canadian museums offer virtual tours in both English and French!<br />

Not only are these museums fun and interesting, they provide a great resource to<br />

experience French outside of the classroom, right at your fingertips.<br />

Royal Ontario Museum – Toronto, ON<br />

Canada’s largest museum and home to a collection of more than 13 million artworks,<br />

cultural objects, and natural history specimens. You can take a virtual tour through<br />

‘Google Art Project’ which lets you explore the different exhibition spaces and also offers<br />

online exhibitions. While most of the museum tour is in English, the museum’s website<br />

is fully bilingual and provides explanations in French about the current exhibits and galleries.<br />

www.rom.on.ca/en/exhibitions-galleries/exhibitions/online-exhibits<br />

Canadian Museum of History – Canadian History Hall /<br />

Salle de l’histoire canadienne – Gatineau, QC<br />

The Canadian Museum of History is Canada’s most visited museum and one of its oldest<br />

public institutions. The museum has 25,000 square metres of display space that highlight<br />

the country’s history and of mankind. Through their virtual gallery you can explore in both<br />

French and English the “Canadian History Hall” which opened in 2017 for Canada’s 150th<br />

anniversary. It encompasses 3 galleries dedicated to Canadian history from its early days<br />

to our modern era. www.museedelhistoire.ca/salle-de-lhistoire/visite-virtuelle<br />

Canadian Museum of War – Ottawa, ON<br />

Canada’s museum of military history in the nation’s capital has exhibitions that cover all<br />

of Canada’s involvement in historic military past, and the role it has played in the world.<br />

Besides having permanent galleries, the museum has special exhibitions throughout the<br />

year, many of which are available online! Head over to this virtual tour whether you<br />

want to learn about Canada’s role in the First World War, its naval history, or simply<br />

the chronology of the country’s military history. Fully bilingual.<br />

www.museedelaguerre.ca/expositions/expositions-en-ligne<br />

Virtual Museum of Canada<br />

The Virtual Museum of Canada is a federally funded program managed by the<br />

Canadian Museum of History that is working to build digital capacity in Canadian<br />

museums and lets Canadians access different exhibitions across the country. This<br />

museum has a great selection of exhibitions ranging from arts, history, nature, science,<br />

among many more topics from different cities around the country. Fully bilingual.<br />

www.museevirtuel.ca/virtual-exhibits/type/expositions-virtuelles<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 5

<strong>CPF</strong> RESEARCH<br />

SUMMARY OF<br />

The State of FSL Education<br />

in Canada 2019 Report<br />

In October, <strong>CPF</strong> launched the 2019<br />

edition of its research series “The State<br />

of French Second Language Education<br />

in Canada Focus on FSL Programs”, this<br />

was the third installment of the series<br />

after Focus on FSL students (2017) and<br />

Focus on FSL teachers (2018).<br />

The 2019 edition offers a review<br />

of current FSL education literature<br />

conducted by Stephanie Arnott and<br />

Mimi Masson to identify key research<br />

findings by FSL program and provide<br />

insight into pedagogical hallmarks and<br />

potential lessons that can be learned<br />

from studies across different programs.<br />

Key themes that are described include<br />

literacy instruction, grammar instruction<br />

and inclusive practices. Particular<br />

attention was paid to research in core<br />

French contexts, especially areas where<br />

innovations could inform other FSL<br />

programs, such as French immersion. Two<br />

such areas were: arts-based instruction<br />

and instructional experimentation.<br />

Given that the three FSL programs<br />

with the most amount of students are<br />

core French, intensive French, and<br />

French immersion, the report also<br />

includes articles for each of them in<br />

an ‘interview’ format with researchers<br />

from each program:<br />

n Focus on Core French:<br />

Sharon Lapkin and Stephanie Arnott<br />

underline the need to infuse new life<br />

into core French programs, calling for a<br />

‘revolution’ entailing a reconsideration<br />

of student motivation and alternative<br />

distributions of instructional time for<br />

this FSL program that serves most<br />

Canadian students.<br />

n Focus on intensive French:<br />

Wendy Carr reviews the history and<br />

successes of intensive French programs,<br />

emphasizing how a literacy-based<br />

approach along with some intensity<br />

of instructional time can provide a<br />

solid foundation for bilingualism.<br />

6 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

BY <strong>CPF</strong> NATIONAL RESEARCH SUPPORT WORKING GROUP<br />

n Focus on French immersion:<br />

Roy Lyster highlights findings from an<br />

extensive review of French immersion<br />

programs, pointing out strengths and<br />

areas for improvement identified<br />

through research. He summarizes<br />

his ‘counterbalanced approach’ to<br />

immersion instruction and outlines<br />

three key ingredients for successful<br />

FSL programs.<br />

Also in this report, an update<br />

shares how the Diplôme d’études en<br />

langue française (DELF) is being used<br />

across Canada as a common standard<br />

for describing and measuring French<br />

proficiency across FSL programs. A list<br />

of recently published documents for<br />

further reading was gathered including<br />

publications from the Council of Ministers<br />

of Education of Canada.<br />

With this report, <strong>CPF</strong> wants to inform<br />

decision makers, federal and provincial/<br />

territorial authorities on the importance<br />

The 2019 report takes an<br />

in-depth look at contemporary<br />

FSL research findings with a<br />

focus on the evolution of core<br />

French, French immersion and<br />

intensive French as well as<br />

trends in literacy instruction,<br />

grammar instruction, and<br />

inclusive practices.<br />

of equality of access for all students<br />

wishing to enroll in FSL programs and<br />

reinforce the role of education leaders,<br />

school jurisdictions and the government<br />

in assuring student achievement in French<br />

as a second language programs.<br />

The <strong>CPF</strong> recommendations include<br />

investments in official language research<br />

such as studying various delivery<br />

models, programmatic innovations and<br />

pedagogical strategies, in supporting<br />

preservice and inservice teacher<br />

education, and funding official language<br />

proficiency assessment practices such<br />

as DELF testing.<br />

We encourage our members to<br />

use this report to continue optimizing<br />

our credibility as a research-informed<br />

organization and also by influencing<br />

the FSL research agenda with factual<br />

information. To download a copy of<br />

the report, visit cpf.ca n

Parents as<br />

Multilingual<br />

Experts<br />

Leveraging families’ cultural and<br />

linguistic assets in the classroom<br />

BY DR. GAIL PRASAD<br />

Reprinted with permission of Education Canada. First published in<br />

December 2017, Vol. 57 (4) – https://www.edcan.ca<br />

Linguistic diversity has become a defining feature of Canadian<br />

classrooms today. Multilingual students, who speak different<br />

languages at home and at school, have become the norm<br />

rather than the exception, particularly in major urban centres.<br />

Take the Toronto District School Board and the Vancouver School<br />

Board: they both report over 120 languages spoken by their<br />

students and their families. It’s not uncommon for teachers today<br />

to have classes filled with students who speak many different<br />

languages at home. At a time when people are constantly on<br />

the go and technology makes it relatively easy to communicate<br />

around the globe 24/7, researchers have observed that children<br />

navigate their different language and literacy practices with<br />

natural ease; they have grown up in a world that depends<br />

on flexible language and literacy practices. Many teachers,<br />

however, don’t share students’ diverse linguistic backgrounds or<br />

experiences with growing up in a digitally mediated world. And<br />

teacher preparation programs often offer little required work with<br />

English learners and their families. Yet as classroom populations<br />

continue to diversify, the need to develop inclusive multilingual<br />

pedagogies also grows.<br />

Are there ways to bridge this divide? How can teachers draw<br />

on students’ diverse cultural assets and build on the linguistic<br />

expertise that students bring into today’s classrooms, rather than<br />

constraining it? Surely, all students should leave school with more<br />

expansive linguistic repertoires rather than losing their home<br />

languages in the process of acquiring the language of instruction.<br />

Further, how can teachers engage parents in their children’s<br />

language and literacy development if parents don’t speak the<br />

language of instruction? Teachers, naturally, don’t speak all<br />

of their students’ home languages!<br />

Multilingual learning<br />

Dr. Jim Cummins has advocated that teachers engage<br />

multilingual students in the creation of what he calls “identity<br />

texts”: students are encouraged to use their home languages<br />

and cultural understanding alongside the language of instruction<br />

to produce multimodal texts for academic purposes that reflect<br />

students’ identities in positive ways. [1] Over the past decade,<br />

researchers and teachers across the country have been putting<br />

this idea into practice through the creation of a range of<br />

continued . . .<br />

WE WANT TO KNOW WHAT YOU THINK. JOIN THE CONVERSATION @EDCANPUB #EDCAN !<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 7

dual-language books, documentaries, installation art exhibits<br />

and dramatic performances.<br />

Beyond the ESL classroom, identity text work can offer<br />

mainstream teachers a powerful strategy for building all students’<br />

appreciation of linguistic diversity and for leveraging students’ and<br />

their families’ multilingual literacy expertise. Over the past seven<br />

years, I have collaborated with classroom teachers across English<br />

and French schools in Canada, France and the U.S. to explore<br />

the affordances, challenges and outcomes of engaging students<br />

collaboratively in multilingual project-based learning (MPBL). Most<br />

recently, I’ve partnered with elementary teachers in Toronto in<br />

English, French immersion and French language schools, as well<br />

as a private school, to design and implement MPBL across content<br />

areas such as social studies and science. [2] Over a two-year period,<br />

we worked with children in Grades 4-6 to produce collaborative<br />

multimodal and multilingual books using English, French and<br />

students’ home languages. Examples of students’ work can be<br />

seen on the project website: www.iamplurilingual.com.<br />

Across these school partnerships, five principles emerged<br />

that can guide teachers and administrators seeking to cultivate a<br />

multilingual orientation and to design collaborative multilingual<br />

inquiry projects to enhance learning and to build social<br />

understanding of linguistic diversity:<br />

1<br />

Draw<br />

2<br />

Invite<br />

3<br />

Group<br />

on the diverse languages of the school community, including<br />

but not limited to incorporating students’ home languages, local<br />

Indigenous languages, and the language(s) of instruction. Even<br />

if your student population does not include many speakers of<br />

other languages, teachers can always incorporate Canada’s official<br />

languages – English and French – local Indigenous languages<br />

and other languages represented across the wider community.<br />

Investigate language resources in your community so you can<br />

cultivate a rich language ecology in your classroom.<br />

parents, families and community members to contribute their<br />

language and cultural expertise to help students bridge diverse<br />

home, school and community language and literacy practices. Parents,<br />

grandparents and other family members may be hesitant to volunteer<br />

in a school where they don’t speak the language of the classroom. Invite<br />

them in to share their languages and experience as multilingual role<br />

models, not only for their children but also for the entire class.<br />

students of different language backgrounds to work<br />

collaboratively on content-based projects, as a context for<br />

developing language and literacy skills along with content<br />

knowledge and understanding. While having students who<br />

speak different languages work together may seem counterproductive<br />

at first, keep in mind that the goal is not that they<br />

become fluent in all of the languages represented, but rather to<br />

develop a welcoming curiosity about languages and one another.<br />

4<br />

Build<br />

5<br />

Publish<br />

students’ metalinguistic awareness explicitly by actively<br />

comparing different languages and how language(s) function, and<br />

identifying patterns for cross-linguistic transfer. Draw students’<br />

attention to how languages work and how they are related. Bridge<br />

from what students already know in their home and community<br />

languages to the language of instruction.<br />

collaborative multilingual projects for authentic audiences<br />

through an end-of-project celebration, and through the use of<br />

technology to reach broader audiences. Celebrate students as creative,<br />

multilingual producers rather than consumers. Plug into other schools,<br />

community groups and families to share the multilingual work that<br />

students generate to extend it beyond your classroom and to receive<br />

feedback and inspiration to keep on.<br />

Students’ reflections about themselves and their work speak to<br />

the importance of inviting students’ languages into the classroom.<br />

One student said about her group’s multilingual book, “No one<br />

knew I can speak Swahili before. It’s like now they know me for<br />

real.” Another student commented, “My work makes me feel<br />

original. I am the only person in the class who can read and write<br />

these three languages and that makes me special.” And yet another<br />

student remarked, “Before this project, I never liked reading and<br />

writing. Now I think I like it!” These powerful identity statements<br />

highlight how supporting students’ use of their home languages<br />

within the classroom increases their engagement; consequently,<br />

they produce high-quality work in which they take pride.<br />

Engaging parents<br />

Beyond the students’ positive responses, teachers consistently<br />

report that doing multilingual work with students shifts<br />

how they see culturally and linguistically diverse parents.<br />

MPBL creates an authentic opportunity to invite parents into<br />

the classroom and the school as language and literacy experts.<br />

This positioning of multilingual parents as having valuable<br />

language expertise allows parents who might otherwise feel<br />

marginalized because they don’t speak the language of the<br />

classroom, to feel welcome into the school. Furthermore, when<br />

teachers host celebration events to present students’ multilingual<br />

work to their families, teachers have noted that they have greater<br />

turnout and that in many cases, parents and extended family<br />

members have come to the school for the very first time. As<br />

one teacher explained, in reference to newcomer families:<br />

“ I’ve seen a greater confidence of parents in school… the fact<br />

that we valued their home language and culture within our<br />

French class allowed parents to be involved in the learning of<br />

French in some way. Even if it may seem paradoxical, the fact<br />

that we purposefully drew on their family’s language created a<br />

reassuring context for engaging in learning. They knew that we<br />

were not trying to exclude their culture or their identity.”<br />

8 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

In my interviews with parents, I’ve found myself surprised by<br />

parents’ expressions of appreciation that the school affirmed to<br />

their child the value of their family’s home language and culture<br />

through MPBL. The sense that has emerged is that MPBL builds<br />

reciprocal relationships among teachers and families. One mother,<br />

for example, who had compared trying to get her daughter to<br />

learn Farsi to forcing her to eat her vegetables, recounted:<br />

“[My daughters] weren’t curious about this ‘other’ language<br />

for a long time and the writing the translation in Farsi was a<br />

good thing and [my daughter] was happy that I could actually<br />

do it for her… it kind of opened up the door a little bit. Like<br />

she now thinks she’s more interested in the language.”<br />

When schools affirm students’ home languages and cultures,<br />

parents become language and literacy experts in the eyes of their<br />

children, and multilingual parents are empowered to actively<br />

participate in their child’s learning at school and at home.<br />

Another parent further explained how valuable it is for parents<br />

to have their children’s home languages affirmed by the school:<br />

“ I think the project has been good for [my daughter] because I<br />

think sometimes you need to mirror back to a child what they<br />

have… It hasn’t been apparent to them as a gift possibly and<br />

so having the school… pay attention to that is a way of saying<br />

to them, ‘You guys have gifts! [It’s] a really lucky thing that you<br />

have access to another language!’ It’s also powerful when it<br />

comes from teachers… As a parent when you hold the mirror up<br />

to your child to say, ‘This is the wonderful gifted person I see you<br />

are,’ it’s like, ‘Whatever, Mom.’ I think [kids] dismiss it. I think<br />

they’re pleased on one level but you as a parent sometimes<br />

don’t have as much weight. But when an external person<br />

validates that, it gives them a level of thoughtfulness about<br />

themselves that they don’t necessarily get when it’s just a<br />

parent mirroring back… When it’s valued elsewhere it’s a<br />

solid reinforcement!”<br />

My current research investigates MPBL as a school-wide<br />

strategy for building multilingual language awareness and<br />

intercultural understanding with a local elementary school in<br />

Madison, Wisconsin. In this work, parents’ reflections about<br />

their children’s collaborative multilingual work continue to<br />

affirm that teachers and parents must be partners in raising<br />

children to become thoughtfully engaged citizens in our diverse<br />

world. In closing, listen to the responses of parents following<br />

the creation of multilingual class books with five Grade 1<br />

classes as part of a science unit about plants:<br />

“I was so pleased with the book I was almost brought to tears.<br />

Particularly considering the xenophobia in our culture today, it’s<br />

a wonderful way to promote the inclusion of different languages<br />

and cultures. Thank you!”<br />

“I think it was great to have [children] working on something together.<br />

This book is definitely something we will keep and reflect back on and<br />

share with other family members.”<br />

“We wished we could have contributed with a foreign language of<br />

our own! [ Our son] can recognize the different languages (mostly)<br />

on sight. He was very proud of being able to say a few sentences<br />

in Arabic.”<br />

“My sense is that seeing… languages together in the book gives<br />

children the visual reminder of other classmates’ perspective. This<br />

project seems original, creative and useful!”<br />

Around the world where racial, linguistic, religious and political<br />

differences threaten to divide communities, the need to build bridges<br />

among teachers, students and families from diverse backgrounds is<br />

critical. Affirming and leveraging students’ cultural and linguistic assets<br />

helps move towards building more inclusive schools and gives students<br />

an opportunity to learn how to work together across their differences,<br />

within the microcosm of their classrooms. n<br />

This parent’s reflection highlights that MPBL can forge<br />

mutually beneficial relationships among teachers, students<br />

and parents that multiply opportunities to affirm children’s<br />

identities as they integrate creatively their home and school<br />

language and literacy practices.<br />

[1] J. Cummins and M. Early, Identity Texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools (London: Trentham, 2001).<br />

[2] This research was generously supported by a Joseph Armand-Bombardier Canada Graduate scholarship (2010-2013) from the Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council.<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 9

Celebrating<br />

40 Years of<br />

Canadian Parents for French<br />

SASKATCHEWAN<br />

BY KAREN POZNIAK, BRANCH EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR<br />

In August 2019, Canadian Parents for French Saskatchewan<br />

formally celebrated its 40th anniversary with a President's<br />

Reception. Supporters gathered for an evening of music and<br />

camaraderie. The mood was light and friendly, the hors d'oeuvres<br />

were plentiful and delicious, the beverages were refreshing, and the<br />

crowd mixed and mingled and shared stories. What a lovely evening<br />

it turned out to be!<br />

Janet Loseth, the incoming Branch Board President, welcomed<br />

the guests by saying, “We are immensely pleased to see so many<br />

people here. There are representatives from government attending<br />

and from our Francophone partners. There are current and former<br />

members present. Hélène Grimard, our Volunteer of the Year<br />

recipient for 2018-2019, is here. For a period of time which spans<br />

36 years, Hélène has been a judge at the Provincial Final of Concours<br />

d'art oratoire. She is a shining example of our greatly appreciated<br />

volunteers. We would never have gotten to this milestone, the<br />

40th anniversary, without the Hélène's of this world ... the many,<br />

many, many dedicated volunteers, staff, partners, supporters,<br />

funders, who helped to get us to this day."<br />

The Honourable Gordon Wyant, Deputy Premier and Minister<br />

of Education, could not attend but did prepare a letter which<br />

Ms. Loseth read out to the crowd. In part, his comments included,<br />

"On behalf of the Government of Saskatchewan, I would like to<br />

commend Canadian Parents for French (<strong>CPF</strong>) Saskatchewan on<br />

celebrating 40 years of furthering bi- and multilingualism in our province<br />

and country. The opportunities provided by your organization<br />

to not only Saskatchewan's youth, but all citizens of this country, is a<br />

beaming indication of the cultural growth and diversified success of all<br />

those who call Canada home. After four decades, <strong>CPF</strong> Saskatchewan<br />

can proudly assert that they have done an outstanding job in supporting<br />

our students and citizens as they learn the French language."<br />

Derrek Bentley, Vice-President of the National Board of<br />

Directors, brought greetings on behalf of Canadian Parents for<br />

French. National Board Director Richard Slevinsky also attended.<br />

Kelly Block (Conservative Member of Parliament for Carlton Trail -<br />

Eagle Creek) and Sheri Benson (New Democratic Member of<br />

Parliament for Saskatoon West, at the time) spoke to the contributions<br />

made and the role the organization has and is playing in<br />

fostering support for official bilingualism. Ms. Benson presented<br />

Ms. Loseth with a framed commemorative certificate.<br />

Denis Simard, President of the Board of Directors of<br />

l’Assemblée communautaire fransaskoise, congratulated the<br />

volunteers and staff, and remarked, in part, "Canadian Parents for<br />

French has played one of the most significant roles in changing<br />

attitudes, influencing decision makers and molding public opinion<br />

facing our bilingualism."<br />

In conclusion, Ms. Loseth added, "For 40 years, Canadian<br />

Parents for French Saskatchewan has been an informed and<br />

passionate advocate for all who value Canada's official bilingualism.<br />

The organization has used solid research to educate the populationat-large<br />

about the value of bilingualism within the multilingual and<br />

multicultural tapestry that is Canada."<br />

After the program, guests stayed and continued to enjoy the<br />

musical styling of Crestwood, the food and the company. n<br />

10 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

“<br />

The efforts of <strong>CPF</strong> Saskatchewan truly do help to bring<br />

a positive change to our communities as we come<br />

together to broaden our linguistic opportunities. I would<br />

like to applaud you for your on-going and dedicated<br />

work in supporting the French language in our great<br />

province, and Canada as a whole. Best wishes for a fun<br />

and exciting event, and congratulations on 40 years<br />

of excellence.<br />

”<br />

The Honourable Gordon Wyant, Deputy Premier and Minister of Education,<br />

Government of Saskatchewan<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 11

<strong>CPF</strong> EVENTS<br />

Officially<br />

A Conference Marking<br />

50 Years of Linguistic Duality<br />

and Education in Canada<br />

Je suis fier d’être un canadien bilingue<br />

BY GORDON CAMPBELL WINNIPEG, MB<br />

I was fortunate to be invited to speak at this conference held in Gatineau, November 21-13, 2019, co-hosted by the Association for<br />

Canadian Studies, Canadian Parents for French and the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. The event brought together<br />

different public sectors involved and concerned with Canada’s two official languages.<br />

It was a unique opportunity where, not only educators, but civil servants, policy writers, university students and researchers were able<br />

to speak together about Canada’s linguistic duality, Canadian perceptions about language learning and official language bilingualism.<br />

DAY 1 The first day of the conference started with a keynote<br />

presentation by Matthew Hayday, history professor at the<br />

University of Guelph, who started by saying that he was also<br />

present 10 years ago at the 40th anniversary of the Official<br />

Languages Act and added that “so little has changed in<br />

regards to second language education”.<br />

Hayday noted the main challenge for immersion education<br />

is finding qualified, trained, bilingual teachers – those who<br />

have an understanding of immersion and second language<br />

pedagogy, are knowledgeable about the subject matter they<br />

are teaching and are also able to speak French fluently.<br />

Prof. Hayday emphasized that research points to the fact<br />

that students can learn in an immersion program to the same<br />

extent that students can learn in an English program, but that<br />

adequate support and resources need to be in place to support<br />

struggling learners. If adequate supports are not provided,<br />

teachers will struggle to accommodate all learners, students<br />

will leave the program and the myth perpetuates itself.<br />

12 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

<strong>CPF</strong> EVENTS<br />

Nancy McKeraghan, <strong>CPF</strong> National President<br />

Prof. Hayday also spoke about<br />

what it means to be bilingual and<br />

how Canadians in different parts of the<br />

country view bilingualism. Definitions are<br />

changing. In some instances the word<br />

Francophone now is meant to include<br />

all people who speak French and or live<br />

in the French culture. This brought an<br />

interesting perspective to the ensuing<br />

discussions. As someone who does not<br />

speak French as a first language, can one<br />

or does one consider themselves to be<br />

Francophone?<br />

One participant working in Quebec<br />

identified as a Franco-Ontarian. French<br />

was her first language. She felt that<br />

although she was perfectly bilingual<br />

and working in Quebec, she was still not<br />

integrated into Quebec’s society and<br />

culture. She was proud of her “identité<br />

de francophone minoritaire” and hopes<br />

that in speaking to people in Quebec<br />

they grow to realize that there are many<br />

Francophone people living outside the<br />

province who speak French as their<br />

primary language of communication.<br />

DAY 2 The keynote speaker,<br />

multi-disciplinary Franco-Ontarian<br />

artist/musician Yao, born in Ivory Coast,<br />

informed us that the largest French<br />

speaking city in the world is now Kinshasa<br />

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.<br />

He stated that when he is in Africa, he<br />

identifies simply as a man. In North<br />

America he first identifies as a black man,<br />

then as a black man from Ontario who<br />

speaks both French and English. Labelling<br />

who we are becomes an issue, but as<br />

language learners, identity is an issue. One<br />

Indigenous participant reminded us of our<br />

euro-centric viewpoints, and that both<br />

English and French were the languages<br />

of colonizers. The Official Languages Act<br />

does not consider indigenous languages,<br />

although we are beginning to accept<br />

and appreciate the importance of these<br />

languages to the Canadian mosaic. We<br />

speak about a linguistic duality, but there<br />

are so many perspectives and definitions<br />

that we need to broaden our understanding<br />

of the plurality that is Canada.<br />

DAY 3 This day began with a viewing<br />

of parts of the film “Bi” a Radio-Canada<br />

documentary about bilingualism in our<br />

country. Although about bilingualism,<br />

the film could not be made bilingually,<br />

or even sub-titled in English, because<br />

Radio-Canada would not fund the project<br />

if there was too much English content.<br />

Yao also referred to this challenge in<br />

the artistic community. If a French<br />

artist works with an English artist and<br />

there is too much English content then<br />

funding is not available to support<br />

the project.<br />

Media personality Tasha Kheiriddin,<br />

reinforced the idea of the two solitudes<br />

within the journalism profession<br />

in Canada, with very few journalists<br />

understanding and working in both<br />

English and French. Producers are<br />

often not interested in looking at<br />

projects from outside of the majority<br />

culture.<br />

The film pointed out some of<br />

the challenges in immersion education,<br />

but unfortunately did not look at the<br />

many positive stories from across the<br />

country, where a young population of<br />

immersion students are changing the<br />

definition of what it means to be<br />

bilingual in Canada. I felt the film,<br />

although raising many significant<br />

issues with regards to bilingualism,<br />

immersion education and identity,<br />

lacked a perspective from Western<br />

Canada, particularly Manitoba and its<br />

many successful immersion programs.<br />

In a panel discussion following<br />

the film, Graham Fraser, former<br />

Commissioner for Official Languages,<br />

spoke about the success of the French<br />

immersion program, but also about<br />

the challenges of immersion educators<br />

responding to the needs of all children.<br />

I asked him if he was familiar with Tara<br />

Fortune’s work “Struggling Learners and<br />

Language Immersion Education”, an<br />

excellent resource for all educators<br />

which dispels so many myths about<br />

second or additional language learning.<br />

French immersion educators must<br />

work diligently to dispel myths about<br />

immersion education and advocate for<br />

increased supports to help all students<br />

with their learning.<br />

I am grateful to have had the<br />

opportunity to be part of such dynamic<br />

and relevant discussions about<br />

bilingualism, identity and Canada’s<br />

linguistic duality/plurality.<br />

“ Si on me donnait un seul vœu, ce serait<br />

de parler toutes les langues qui existent<br />

et qui ont existé à travers les années.<br />

Juste à cause de la richesse culturelle<br />

que tu pourrais acquérir. »<br />

– Yaovi Hoyi (Yao)<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 13

<strong>CPF</strong> EVENTS<br />

Didn’t We Learn This Already?<br />

Fifty Years of Official Languages, Bilingualism and Education<br />

BY MATTHEW HAYDAY UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH | MHAYDAY@UOGUELPH.CA | TWITTER: @MHAYDAY<br />

Matthew Hayday<br />

PRESENTATION NOTES<br />

u In preparing my notes for my talk this morning, I realized<br />

that had spoken at a similar conference organized by the<br />

Association for Canadian Studies ten years ago, on the<br />

occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Official Languages.<br />

u I am a historian who has studied official languages,<br />

bilingualism, and second language learning in Canada<br />

over the past twenty years, and it absolutely gob-smacks<br />

me that so little progress is made on some of these fronts,<br />

and how much we see repeating from the past.<br />

u Which is what inspired the title of my talk: Didn’t we learn<br />

this already?<br />

New Threats and Opportunities<br />

u We are facing a deeply fragmented landscape at the<br />

provincial level when it comes to the questions of<br />

bilingualism and FSL and the will of provincial<br />

governments to take positive initiatives.<br />

u Recall that when it comes to polling data, Canadians<br />

tend to be most open on this issue of language learning<br />

opportunities for children – when it comes to the scope<br />

of various language-related services – things get more<br />

difficult as you progress into other sectors, and to services<br />

that are more explicitly targeted at francophones alone.<br />

Where Do We Go from Here?<br />

u A large part of the work for organizations like <strong>CPF</strong> and the<br />

OCOL, and the many francophone associations across<br />

the country is going to have to be about protecting what<br />

programs and rights currently exist against hostile regimes.<br />

u The short-term challenge is going to be to maintain pressure<br />

on Ottawa to continue its funding and advocacy role in this<br />

sector, much as we might have hoped that the provinces<br />

would have fully taken this on decades ago.<br />

u The longer-term challenge is to address the issue of bringing<br />

the mass of English-speaking Canadians – not just French<br />

immersion parents – back around to the perspective that<br />

second-language learning for themselves, and two official<br />

languages for the country as a whole is an asset for them<br />

personally and the country<br />

u Currently, there is clearly a demand – and one that goes well<br />

beyond government-based jobs – for people with language<br />

skills – in both French and other languages.<br />

u The challenge is conveying to Canadians the idea that learning a<br />

second language isn’t just something that you do if you want to<br />

work for the federal government or teach – but that it will have<br />

a much wider-based applicability and usefulness in their lives.<br />

u I think it’s important to realize that the context in which we are<br />

living has changed in some substantive ways from when the<br />

official languages regime was created and stabilized. n<br />

14 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

Discover our<br />

INTEGRATED<br />

FRENCH IMMERSION<br />

OPTION<br />

www.usainteanne.ca<br />

ASK JOSÉE<br />

about scholarships!<br />

Did you know you can earn a degree and<br />

learn French at the same time? Count<br />

French credits towards you program and<br />

graduate with no delay.<br />

FOR MORE INFORMATION<br />

In the context of today’s highly competitive<br />

job market, bilingualism is a valuable asset<br />

that opens doors to employment opportunities<br />

nationally and internationally. By living,<br />

studying, working and playing in French 24<br />

hours a day, you will develop the confidence<br />

and proficiency you need to succeed.<br />

Josée Gauvin<br />

recruitment@usainteanne.ca<br />

902-769-2114, ext. 7372

WAYS<br />

5TO ACHIEVE TOTAL<br />

IMMERSION IN A<br />

LANGUAGE WITHOUT<br />

LEAVING YOUR HOUSE<br />

BY BRANDON DERIGGS ORGANIZATIONAL CONSULTANT, WRITER AND AUTHOR<br />

We all know that the best way to learn a new language is to immerse ourselves in it. But going<br />

back to school or traveling to a foreign country isn’t always possible. Here are five surefire ways<br />

to help you learn French or English without having to leave the comfort of your home.<br />

1<br />

Change all your technology<br />

settings to French or English<br />

Standard ways of learning a language<br />

include going to a classroom, getting a<br />

tutor, and doing a bunch of drills and exercises. In other<br />

words, it usually requires some form of repetition and<br />

practice. In reality, most people tap out after a few hours<br />

of study, since studying is not exactly an activity they can<br />

do the entire day. You can, however, switch your smartphone,<br />

TV or computer settings to French or English and devote an<br />

entire day to using these devices in your second language.<br />

That means every time you look at your screens and interact<br />

with them, you’re building new language muscles with the<br />

neurons in your brain in a manner that requires your utmost<br />

attention. Now, what was second nature, such as sending an<br />

email or text, browsing the web, or watching your favorite<br />

TV show, begins to require a concentrated effort to formulate<br />

and understand words.<br />

2<br />

Listen to songs in your<br />

target language<br />

Most people listen to music, as it is one of the<br />

simple pleasures of life. It can change one’s<br />

mood and act as a bridge of communication between different<br />

cultures. To have a fully immersive experience, only listen to<br />

songs in your target language (French or English). You may not<br />

understand the words being sung, but you’ll feel the emotion.<br />

Later, you can look up the translated lyrics and keep repeating<br />

the process.<br />

3<br />

Listen to a radio station in<br />

your target language<br />

Is there a radio station you like to listen to? What<br />

about a French or English radio station? Try listening<br />

in your target language as you go about doing your daily chores<br />

and tasks. You may not catch every word, but you’re subconsciously<br />

absorbing all the new information. Certain words,<br />

certain sounds, certain feelings will pop up, and you’ll be able to<br />

make associations. As your knowledge of your target language<br />

grows, you’ll make more associations, because you’ve heard a<br />

word before but now it has meaning.<br />

16 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

4<br />

Read books in French<br />

or English<br />

Read books in your target language.<br />

Depending on your ability, you can read<br />

anything from children’s books to full-length novels. Books tell<br />

stories. Stories have emotional, meaningful events that allow<br />

them to be memorable to us. When you experience stories in<br />

a new language, you’ll have an easier time recollecting your<br />

vocabulary because of the events associated with the words.<br />

With these five methods, you’ll be well on<br />

your way to speaking French or English with<br />

ease and without having to leave your house.<br />

How about you? Are you trying to learn, or<br />

have you learned, a new language? If so, do<br />

you have any tips or strategies that you’d<br />

like to share?<br />

5<br />

Speak out loud<br />

to yourself<br />

Speak out loud to yourself if there’s no one<br />

to practise with. When people move to<br />

foreign countries, they have to speak in order to accomplish<br />

anything. If you’re at home watching a show or movie, reading<br />

a book, or listening to music, and you hear or read a phrase<br />

that you like, try repeating it and using it in as many contexts<br />

as possible. The next time you’re able to speak to a native<br />

speaker, try it on them and see what happens! n<br />

The article was first published on April 29, 2019, in the Language Portal of Canada’s Our<br />

Languages blog. A Translation Bureau initiative, the Language Portal provides Canadians<br />

with a wide range of resources to help them communicate more effectively in English and<br />

French, and publishes weekly articles by language lovers on the Our Languages Blog.<br />

www.noslangues-ourlanguages.gc.ca/en/blogue-blog/<br />

immersion-a-la-maison-immersion-in-your-house-eng<br />

D I S C O V E R<br />

INTERACTIVE ACTIVITIES<br />

LITTÉRATOUT www.litteratout.ca<br />

READ ALOUD BOOKS<br />

INTERACTIVE VIDEOS<br />

Interactive literacy activities and books<br />

to engage your child in reading,<br />

writing and speaking French!<br />

Family Junior plan now on<br />

sale for a limited time!<br />

Start your FREE trial today!<br />

www.litteratout.ca/familyplan<br />

<strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong> 17

<strong>CPF</strong> RESOURCES<br />

My Experience with Encounters with Canada<br />

BY EMILY BANCROFT<br />

Looking for an amazing, one week trip to the nation’s capital, to explore potential<br />

career options, try new things, with kids aged 14-17, from coast to coast to coast,<br />

for under $1000? Then Encounters with Canada, Canada’s largest youth forum,<br />

located in Ottawa, Ontario, is the place for you. I knew that once I heard about the<br />

program, from my high school in Delta, British Columbia, I had to apply!<br />

What better way to get out of your comfort zone and meet new people than with<br />

this program. As an aspiring journalist, looking to get a degree in communications, I<br />

chose the week of “Media and Communications”, to further my understanding of the<br />

field and learn if I am truly interested in pursuing this career. When I arrived at the<br />

Vancouver airport on Saturday morning, I was alone and nervous to start my week.<br />

In less than an hour of waiting to take off, I had made 15 new friends from my own<br />

province, who were equally excited to begin the adventure. By Sunday night, I had<br />

gotten around to knowing the name of a vast majority of the people here and learning<br />

more about the culture outside of the west coast. Growing up just outside of a big city<br />

like Vancouver, I am used to the hustle and bustle of downtown Ottawa. It was such<br />

a cool experience to be with kids who had never had the exposure of being in a city as<br />

fast-paced and exciting as this one. Each person that walks through the doors of the<br />

Historica Canada Centre has their own story to share, and by learning more about others,<br />

you begin to appreciate even more the beautiful country of Canada.<br />

In addition to the wonderful people at Encounters, we get the opportunity to<br />

participate in many cultural and theme-specific activities, meaning that the activities<br />

you do will correspond to the week you selected during the application. For my media<br />

and communications week, we were involved in many social games and activities. My<br />

personal highlights were attending a youth summit on violent extremism online, which<br />

took place at the Hilton in Gatineau, Québec, and creating a professional web video at<br />

the CBC radio headquarters in Montréal, Québec.<br />

These 2 programs and workshops gave me the chance to challenge myself as an<br />

individual. While at the conference, I had the opportunity to discuss my opinions and<br />

ideas on how hate speech and negative comments influence our views on the world.<br />

Cyber bullying is a very relevant problem in this generation, and we are always looking<br />

for new ways to prevent it. At the summit, I was able to talk about how I think we should<br />

address such issues, with professionals who are looking for a teen’s perspective. At CBC<br />

radio, I opted to participate in an all-French workshop, because I am a French immersion<br />

bilingual student, and am always looking for new ways to practice my second language.<br />

This was very challenging for me, as my French is strong in a classroom, but not so much<br />

in a less formal and more conversational setting. Throughout the day, I became more<br />

comfortable with my own speech, and I picked up a thing or two, as most of my group<br />

was from Québec. These 2 activities were so amazing to be a part of, and I would have<br />

probably never had the option to do either had it not been for Encounters.<br />

I left Ottawa with nothing but positive memories, new friendships and the<br />

reassurance that journalism and communications is the thing for me. We live in the best<br />

country in the world, and I have never been more proud to be Canadian! n<br />

YOUR TEEN CAN SPEND AN ADVENTURE-FILLED AND BILINGUAL WEEK IN OTTAWA!<br />

EXPLORE CAREER PATHS AND MEET PEERS FROM ACROSS CANADA. REGISTER TODAY!<br />

www.encounterswithcanada.ca<br />

LIMITED REBATES AVAILABLE<br />

18 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

U N I V E R S I T É D E S A I N T - B O N I F A C E<br />

OBTENEZ UNE<br />

BOURSE D’ENTRÉE!<br />

Déposez une demande<br />

d’admission avant le 1 er mars !<br />

ustboniface.ca/bourses-dentree<br />

GET AN ENTRANCE<br />

SCHOLARSHIP!<br />

Submit your application<br />

before March 1 st !<br />

ustboniface.ca/en/scholarships<br />

La seule université de<br />

langue française de<br />

l’Ouest canadien.<br />

Winnipeg, Manitoba<br />

Western Canada’s only<br />

French-language<br />

university.<br />

#VisezUSB<br />

/ustboniface<br />

ustboniface.ca

KEY <strong>CPF</strong> CONTACTS ACROSS CANADA<br />

National office<br />

1104 - 170 Laurier Ave. W., Ottawa, ON K1P 5V5<br />

T: 613.235.1481<br />

cpf@cpf.ca cpf.ca<br />

Quebec office & Nunavut support<br />

P.O. Box 393 Westmount, Westmount, QC H3Z 2T5<br />

infoqcnu@cpf.ca qc.cpf.ca<br />

British Columbia & Yukon<br />

227-1555 W 7th Ave., Vancouver, BC V6J 1S1<br />

T: 778.329.9115 TF: 1.800.665.1222 (in BC & Yukon only)<br />

info@cpf.bc.ca bc-yk.cpf.ca<br />

Alberta<br />

211-15120 104 Ave. NW, Edmonton, AB T5P 0R5<br />

T: 780.433.7311<br />

cpfab@ab.cpf.ca<br />

ab.cpf.ca<br />

Northwest Territories<br />

PO Box 1538, Yellowknife, NT X1A 2P2<br />

cpf-nwt@northwestel.net nwt.cpf.ca<br />

Saskatchewan<br />

303-115 2nd Ave. N., Saskatoon, SK S7K 2B1<br />

T: 306.244.6151 TF: 1.800.561.6151 (in Saskatchewan only)<br />

cpfsask@sasktel.net sk.cpf.ca<br />

Manitoba<br />

101-475 Provencher Blvd., Winnipeg, MB R2J 4A7<br />

T: 204.222.6537 TF: 1.877.737.7036 (in Manitoba only)<br />

cpfmb@cpfmb.com mb.cpf.ca<br />

Ontario<br />

103-2055 Dundas St. E., Mississauga, ON L4X 1M2<br />

T: 905.366.1012 TF: 1.800.667.0594 (in Ontario only)<br />

info@on.cpf.ca on.cpf.ca<br />

New Brunswick<br />

PO Box 4462, Sussex, NB E4E 5L6<br />

T: 506.434.8052 TF: 1.877.273.2800 (in New Brunswick only)<br />

cpfnb@cpfnb.net nb.cpf.ca<br />

Nova Scotia<br />

8 Flamingo Dr., Halifax, NS B3M 4N8<br />

T: 902.453.2048 TF: 1.877.273.5233 (in Nova Scotia only)<br />

cpf@ns.sympatico.ca ns.cpf.ca<br />

Prince Edward Island<br />

PO Box 2785, Charlottetown, PE CIA 8C4<br />

T: 902.368.3703 glecky@cpfpei.pe.ca pei.cpf.ca<br />

Newfoundland & Labrador<br />

PO Box 8601, Stn A, St. John’s, NL A1B 3P2<br />

T: 709.579.1776 ed@cpfnl.ca nl.cpf.ca<br />

TF: 1.877.576.1776 (in Newfoundland & Labrador only)<br />

February 3-7, <strong>2020</strong><br />

50:50<br />

French-Second-Language<br />

Education Week<br />

50 years of French<br />

immersion/ans<br />

d'immersion française<br />

50 years of the Official<br />

Languages Act/ans de la Loi<br />

sur les langues officielles<br />

20 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>

CAMP MÈRE CLARAC - SAINT-DONAT<br />

campclarac.ca • info@campclarac.ca<br />

819 424-2261 • 514 322-6912 sans frais

The method that decodes the language.<br />

read.<br />

write.<br />

speak<br />

understand<br />

lire.<br />

écrire.<br />

parler<br />

comprendre