CPF Magazine Winter 2020 Issue

A national network of volunteers, parents and stakeholders who value French as an integral part of Canada. CPF Magazine is dedicated to the promotion and creation of French-second-language learning opportunities for young Canadians.

A national network of volunteers, parents and stakeholders who value French as an integral part of Canada. CPF Magazine is dedicated to the promotion and creation of French-second-language learning opportunities for young Canadians.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

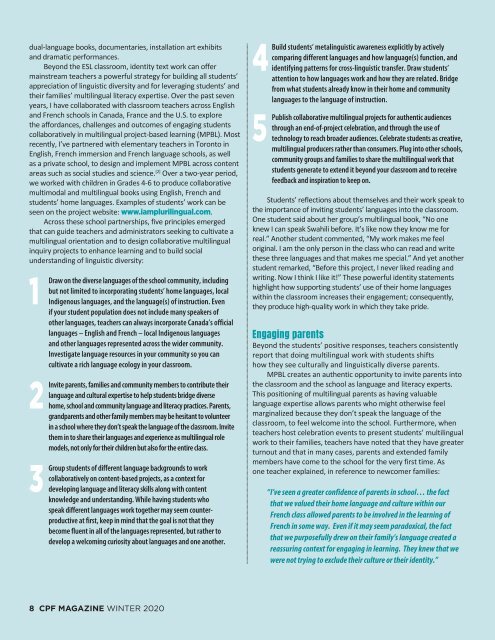

dual-language books, documentaries, installation art exhibits<br />

and dramatic performances.<br />

Beyond the ESL classroom, identity text work can offer<br />

mainstream teachers a powerful strategy for building all students’<br />

appreciation of linguistic diversity and for leveraging students’ and<br />

their families’ multilingual literacy expertise. Over the past seven<br />

years, I have collaborated with classroom teachers across English<br />

and French schools in Canada, France and the U.S. to explore<br />

the affordances, challenges and outcomes of engaging students<br />

collaboratively in multilingual project-based learning (MPBL). Most<br />

recently, I’ve partnered with elementary teachers in Toronto in<br />

English, French immersion and French language schools, as well<br />

as a private school, to design and implement MPBL across content<br />

areas such as social studies and science. [2] Over a two-year period,<br />

we worked with children in Grades 4-6 to produce collaborative<br />

multimodal and multilingual books using English, French and<br />

students’ home languages. Examples of students’ work can be<br />

seen on the project website: www.iamplurilingual.com.<br />

Across these school partnerships, five principles emerged<br />

that can guide teachers and administrators seeking to cultivate a<br />

multilingual orientation and to design collaborative multilingual<br />

inquiry projects to enhance learning and to build social<br />

understanding of linguistic diversity:<br />

1<br />

Draw<br />

2<br />

Invite<br />

3<br />

Group<br />

on the diverse languages of the school community, including<br />

but not limited to incorporating students’ home languages, local<br />

Indigenous languages, and the language(s) of instruction. Even<br />

if your student population does not include many speakers of<br />

other languages, teachers can always incorporate Canada’s official<br />

languages – English and French – local Indigenous languages<br />

and other languages represented across the wider community.<br />

Investigate language resources in your community so you can<br />

cultivate a rich language ecology in your classroom.<br />

parents, families and community members to contribute their<br />

language and cultural expertise to help students bridge diverse<br />

home, school and community language and literacy practices. Parents,<br />

grandparents and other family members may be hesitant to volunteer<br />

in a school where they don’t speak the language of the classroom. Invite<br />

them in to share their languages and experience as multilingual role<br />

models, not only for their children but also for the entire class.<br />

students of different language backgrounds to work<br />

collaboratively on content-based projects, as a context for<br />

developing language and literacy skills along with content<br />

knowledge and understanding. While having students who<br />

speak different languages work together may seem counterproductive<br />

at first, keep in mind that the goal is not that they<br />

become fluent in all of the languages represented, but rather to<br />

develop a welcoming curiosity about languages and one another.<br />

4<br />

Build<br />

5<br />

Publish<br />

students’ metalinguistic awareness explicitly by actively<br />

comparing different languages and how language(s) function, and<br />

identifying patterns for cross-linguistic transfer. Draw students’<br />

attention to how languages work and how they are related. Bridge<br />

from what students already know in their home and community<br />

languages to the language of instruction.<br />

collaborative multilingual projects for authentic audiences<br />

through an end-of-project celebration, and through the use of<br />

technology to reach broader audiences. Celebrate students as creative,<br />

multilingual producers rather than consumers. Plug into other schools,<br />

community groups and families to share the multilingual work that<br />

students generate to extend it beyond your classroom and to receive<br />

feedback and inspiration to keep on.<br />

Students’ reflections about themselves and their work speak to<br />

the importance of inviting students’ languages into the classroom.<br />

One student said about her group’s multilingual book, “No one<br />

knew I can speak Swahili before. It’s like now they know me for<br />

real.” Another student commented, “My work makes me feel<br />

original. I am the only person in the class who can read and write<br />

these three languages and that makes me special.” And yet another<br />

student remarked, “Before this project, I never liked reading and<br />

writing. Now I think I like it!” These powerful identity statements<br />

highlight how supporting students’ use of their home languages<br />

within the classroom increases their engagement; consequently,<br />

they produce high-quality work in which they take pride.<br />

Engaging parents<br />

Beyond the students’ positive responses, teachers consistently<br />

report that doing multilingual work with students shifts<br />

how they see culturally and linguistically diverse parents.<br />

MPBL creates an authentic opportunity to invite parents into<br />

the classroom and the school as language and literacy experts.<br />

This positioning of multilingual parents as having valuable<br />

language expertise allows parents who might otherwise feel<br />

marginalized because they don’t speak the language of the<br />

classroom, to feel welcome into the school. Furthermore, when<br />

teachers host celebration events to present students’ multilingual<br />

work to their families, teachers have noted that they have greater<br />

turnout and that in many cases, parents and extended family<br />

members have come to the school for the very first time. As<br />

one teacher explained, in reference to newcomer families:<br />

“ I’ve seen a greater confidence of parents in school… the fact<br />

that we valued their home language and culture within our<br />

French class allowed parents to be involved in the learning of<br />

French in some way. Even if it may seem paradoxical, the fact<br />

that we purposefully drew on their family’s language created a<br />

reassuring context for engaging in learning. They knew that we<br />

were not trying to exclude their culture or their identity.”<br />

8 <strong>CPF</strong> MAGAZINE WINTER <strong>2020</strong>