The Sea Around Us - Online Catalogue

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

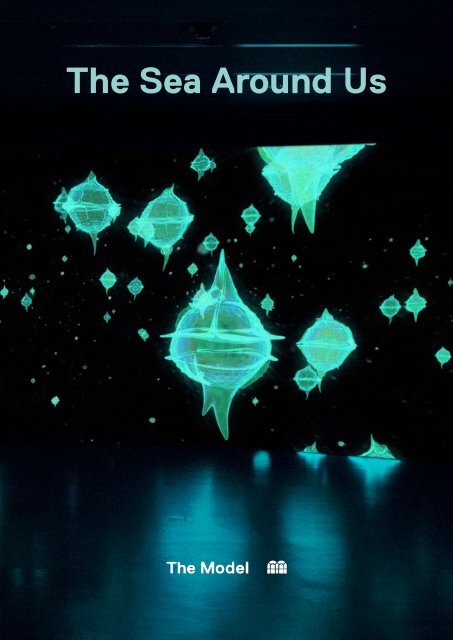

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong><br />

1

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong><br />

John Akomfrah (GH/GB), Forensic Oceanography and<br />

Forensic Architecture (GB), Shaun Gladwell (AU), Karen<br />

Power (IE), Susanne M. Winterling (DE).<br />

Curated by Emer McGarry<br />

<strong>The</strong> Model;<br />

home of <strong>The</strong> Niland Collection<br />

29 Feb. – 31 May 2020<br />

2

Contents<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page | 4<br />

Rosie O’ Reilly . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page | 8<br />

John Akomfrah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page | 16<br />

Forensic Oceanography and Forensic Architecture . . . . . Page | 32<br />

Shaun Gladwell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page | 48<br />

Karen Power . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page | 56<br />

Susanne M. Winterling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page | 66<br />

1<br />

2

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> sea offers us the idea of the infinite, the unknowable. A huge<br />

expanse that invites us to wonder about the limits of our world and<br />

reality. <strong>The</strong> sea has been a source of inspiration to artists, thinkers<br />

and writers for hundreds of years – its sometime serenity juxtaposed<br />

with its sublime terrifying power. <strong>The</strong> sea’s seemingly inexhaustible<br />

abundance and the promise of what lies beyond, have invited humankind<br />

to strike out in exploration in an effort to understand its vastlessness,<br />

and to enrich themselves with the knowledge, sustenance and treasure<br />

they find out there.<br />

<strong>The</strong> sheer immensity of the sea, means it cannot be seen as a clear-cut<br />

theme or topic that can be easily explained or understood. It has many<br />

aspects, and our relationship with it is complex and contradictory. <strong>The</strong><br />

sea is a channel that enables communication and trade, and that casts<br />

knowledge and ideas up on many distant shores. While the sea is a<br />

source of life and abundance, it is also a graveyard, not only for ancient<br />

civilizations, but for the many who bravely risk its depths in search of<br />

peace today. Life within the sea, which once seemed so limitless, has<br />

fallen victim to the actions of the Anthropocene age, and the effects of<br />

this are becoming more scientifically clear all the time.<br />

<strong>The</strong> works in this exhibition invite the viewer to consider the sea as<br />

a setting where a multiplicity of mostly unseen and unknown dramas<br />

are played out, dramas that are at times non-human and at times<br />

inhumane. Through these visual and sound-based works, we invite you<br />

to contemplate the ebb and flow of the ocean, and humankind’s<br />

multi-faceted relationship with it.<br />

<strong>The</strong> show is accompanied by a new music performance and sound<br />

installation by composer and sound artist Karen Power, and a specially<br />

commissioned essay by artist Rosie O’Reilly (IE).<br />

Emer McGarry, 2020<br />

4

5<br />

6

IT DAZZLES ME SLOWLY<br />

by Rosie O’Reilly<br />

Slipping under the surface of the sea I enter an otherworldly<br />

sensorium. Muffled sounds draw my body under, I’m teased<br />

with a feeling of weightlessness and an ability to shapeshift not<br />

always possible on land. I hold my breadth and wonder what it<br />

is that makes this place feel so like home.<br />

7<br />

Asking this question sends me into a speculative<br />

spin where we journey to understand the world<br />

through many different lenses, axes and planes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> boundless possibility of the ocean opens up<br />

an aquatic world of symbolic meaning that I want<br />

to unknot again and again and again. In this place<br />

I am all sensory. This under water place reaches<br />

out and in. Tilting my head, the tidal ripples<br />

lay a hazy path in the sand in front of me. I’m<br />

reminded that these are the tidal patterns that<br />

dictate our terrestrial lives. <strong>The</strong> resonances of<br />

these currents are felt everywhere and it seems<br />

vital to tell the entwined stories of this place. No<br />

one knew this more it seems than Jack B. Yeats<br />

whose abstract brush stokes seem to dance across<br />

different aquatic planes and whose oily figures<br />

shift between the land and sea of his boyhood<br />

town of Sligo. This ability to envisage a new world<br />

through mark and gesture, welcomed strangers<br />

to the west coast of Ireland. Perhaps it is this<br />

ability to view the world through other lenses that<br />

makes art essential now. Never has it been more<br />

important to imagine new worlds, to welcome<br />

strangers and make work that does not stay still<br />

- that comes to meet you in its story telling. Art<br />

then plays a crucial role in helping us ‘stay in the<br />

trouble’ as the cultural theorist and philosopher<br />

Donna Haraway tells us. 1<br />

And these are troubled and stirred up times.<br />

Looking below the surface to investigate led me<br />

to an invasive algae, Undaria pinnatifidais, which<br />

I began tracking in Porto in 2017. I find it today in<br />

Kilmore Quay, Waterford, and in Dún Laoghaire<br />

harbour. 2 Originally from Japan, it is migrating<br />

slowly around the coast of Ireland; hitchhiking<br />

on our leisure vessels and being welcomed by<br />

the warming waters of this new world. While<br />

its population expands and proliferates in local<br />

waters, we watch as the sixth greatest species<br />

extinction gets closer. In Dublin Port gallons<br />

of ballast water from container ships empty<br />

thousands of its spores among other species into<br />

the water, while in the belly of the vessels climatedisplaced<br />

humans risk their lives in refrigerated<br />

units. Coastal areas have always been collision<br />

points for these entwined human and non-human<br />

stories and now, in order to understand these<br />

strange and difficult times, we must unknot them<br />

as they wash up together on sandy shores.<br />

I am drawn down; resisting the urge to breathe I<br />

dive deeper. Again I hear Haraway ‘... it matters<br />

what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it<br />

matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts<br />

think thoughts’. 3 What stories can this aquatic<br />

space reframe if we let it? <strong>The</strong> ocean and tides<br />

challenge borders, carrying and depositing as they<br />

move. <strong>The</strong>se global waves offered our ancestors<br />

an escape to another world as they lifted their<br />

oars and let the current guide them. It is easy to<br />

see how our island ancestors saw this place as<br />

one of mythology and magic, a place to escape<br />

entrapment. Moving with it means an acceptance<br />

of new cycles and paths and of the unknown.<br />

Things ripple and reoccur unresolved on the<br />

same shore. This is the thinking of the ocean;<br />

unknotting our entwined relationship with it<br />

may offer refuge and build new worlds in these<br />

dangerous times.<br />

Unknotting an Evolutionary Tale:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> and <strong>Us</strong><br />

It is May 2007, Stephen Munro, an archaeologist<br />

at Australian National University began<br />

photographing a collection of shells gathered in<br />

Java in 1891 by Dutch anthropologist Eugene<br />

Dubois as he searched for the link between homo<br />

sapiens and ape. <strong>The</strong> photographs revealed<br />

overlooked fossilised evidence that has now<br />

become part of an alternative story of human<br />

8

evolution. Under examination the shells showed<br />

deliberate zigzag markings and small punch holes<br />

made with a shark tooth. Dating placed them as<br />

the oldest markings made by our kind and points<br />

to the bountiful intertidal zone as playing a key<br />

role in our evolution. 4 It seems the Neanderthal’s<br />

recognised the potential of this aquatic foraging<br />

zone too with recent excavations of skull bones in<br />

coastal areas showing the occurrence of Surfer’s<br />

Ear, a condition where dense bony growths<br />

protrude into the external auditory canal after<br />

continued submersion of the skull in water. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

too knew the value of the ocean for survival and<br />

learned to dive for food like clams and seaweed<br />

in order to do so. Could it be we learnt to swim<br />

before we walked? 5<br />

However, the standard story of our evolution in<br />

the 20 th century is the Savannah theory. A harsh<br />

theory that proposes that we separated from<br />

our primate cousins when the forests receded<br />

and we were forced to venture onto the African<br />

Savannah, evolving to bipedal mammals in order<br />

to hunt and kill, to survive, with the male of the<br />

species leading the fight. <strong>The</strong> ability to use tools<br />

developed in order to achieve these primary goals.<br />

This story has fit nicely with many powerful<br />

stories since it became dominant in the 1920s. <strong>The</strong><br />

dangerous stories of warfare and technological<br />

advancement at any cost seems closely allied<br />

with a theory of evolution that focuses on one<br />

species, one gender, fighting to survive. But as<br />

with all stories, ‘it matters what stories we tell<br />

these stories with’ and from the 1960s on, many<br />

academics and researchers have asked ‘did human<br />

kind begin on the dry wide Savannahs as hunters<br />

of Africa, or were our origins beside lakes, rivers<br />

and the sea shore, foraging and shallow diving in<br />

the intertidal zone?’<br />

<strong>The</strong> Aquatic Ape theory, developed by the British<br />

Biologist Alistair Hardy in the 1960s, was met<br />

by contemporary ridicule. 6 He proposed that<br />

certain apes evolved into humans when they<br />

descended from the trees to live, not on the<br />

Savannah but beside the sea, where they could<br />

follow tidal patterns and harness its bountiful<br />

aquatic resources, learning to walk with water as<br />

a support to transition into bipedal beings. One<br />

key question that pointed Hardy towards this new<br />

thinking was asking why, in particular in women,<br />

do humans have a thick layer of sub-cutaneous<br />

fat under their skin? We share this only with the<br />

aquatic mammals he pointed out - nowhere is it<br />

seen in terrestrial kind. Mostly ignored, Hardy’s<br />

ideas were picked up by a popular science<br />

enthusiast and feminist playwright, Elaine<br />

Morgan. Hugely frustrated by the Savannah theory<br />

that left women out of the narrative of human<br />

evolution, Morgan became dedicated to weaving<br />

an alternative story and published ‘<strong>The</strong> Aquatic<br />

Ape’ in 1982. While there isn’t the space here to<br />

offer up both sides of this argument, it is safe to<br />

say that her book has been key in the turning of<br />

the tide. As fossil evidence is continually revisited<br />

and prominent figures like the palaeontologist<br />

Philip Tobias and Sir David Attenborough get<br />

behind the theory, there is at last an aquatic lens<br />

firmly on the story of our evolution.<br />

<strong>The</strong> telling of our evolutionary story through a<br />

watery lens makes my focus soften. <strong>The</strong> status<br />

quo becomes blurred and I’m shifting planes,<br />

building a world view where our greatest resource<br />

was the sea, and the earliest art was scraped on<br />

shells in sea caves. As we followed the ebb and<br />

flow of the tide, we learnt to understand the world<br />

through an aquatic lens.<br />

Swimming in the Mesh:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> as a Sensorium for New Thinking<br />

If we allow the story of our evolution to be tied<br />

closely to this place, the ocean offers ample<br />

metaphorical space to be dazzled. Thinking in<br />

this watery way draws me to two prominent<br />

cultural theorists whose writing ushers us to<br />

think across planes and axes in order to create<br />

space for new visions and tales. In doing so they<br />

propose new modes of aesthetic and ethical<br />

relationship with nature - with the non-human and<br />

with the ocean. Both lay down new tools for us to<br />

rediscover the potential of the sea as something<br />

with which to think and build new worlds. Donna<br />

Haraway’s hybrid thinking binds both human<br />

and non-humans together through what she<br />

calls ‘speculative fabulation’. This is a space very<br />

different to the use of ‘narrative’ in literary theory.<br />

It is a world of wild facts; facts that are never<br />

still, constantly moving and reforming. Drawing<br />

from the metaphor of fables, this is a webbed-like<br />

mesh structure for exploring ontological questions.<br />

Infinite layers exist with no definite backgrounds<br />

or foregrounds, structures are porous and<br />

existence is everywhere. Timothy Morton echoes<br />

Haraway’s interspecies ‘fabulations’ through<br />

his Dark Ecology, 7 a similar mesh-like structure<br />

where the romantic framework of nature as<br />

something ‘over there’ comes crashing down. We<br />

are confronted with the realisation that we exist<br />

in the shadow of a strange ‘other’. This strange<br />

stranger is the recognition that our social space is<br />

in fact borderless and we co-exist with the nonhuman;<br />

be it the ocean, the climate, a sea snake<br />

or a sardine. Haraway and Morton both point to a<br />

strange mesh where the ocular does not dominate<br />

and multisensory languages communicate across<br />

boundaries. I cannot help but think this is the<br />

language of the oceans.<br />

Rediscovering the ocean as a metaphor to<br />

challenge frameworks and communicate with<br />

is evident throughout history, from Melville’s<br />

great whale to the writing of Barbadian poet and<br />

historian Kamu Braithwaite. His poetry springs<br />

from the Atlantic and his ‘tidalectic’ thinking is the<br />

focus of a publication by the same name edited<br />

by the Thysseen-Bornemisza Academy and MIT. 8<br />

Tidalectics brings artists into focus who, like<br />

Yeats use the sea to welcome people to another<br />

world. Brathwaite’s thinking frames these works,<br />

and diving into his world we enter the realm of<br />

the ocean, ‘his poetry mirrors the fluctuating<br />

rhythmic soundings of the waves at sea and their<br />

curling ripples as they wash to the shores’. 9 He<br />

proposes the ‘tidalectic’ as a rejection of western<br />

linear thinking. <strong>The</strong> tide never returns to the same<br />

shore and, as with the tides, his words swell and<br />

dissolve terrestrial modes of thinking; ‘a being<br />

dedicated to water is a being in flux’ Briathwaite<br />

tells us.<br />

A <strong>Sea</strong> in Crisis<br />

<strong>The</strong> 20 th century has seen humankind defined by<br />

linear thinking and not by thinking in flux. With<br />

this we have lost the ability to grasp the expanse<br />

of the water bodies that make up two thirds of our<br />

planet. This detachment brings crisis. <strong>The</strong> sea is<br />

the most dynamic and sensitive component of our<br />

living planet, yet the least known. It is now in a<br />

new phase of its history, markedly shaped by the<br />

impact of human activities on the earth system.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Fifth Assessment Report published by the<br />

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change<br />

(IPCC) in 2013 tells us the ocean has ‘absorbed<br />

93% of the extra energy from the enhanced<br />

greenhouse effect, with warming now being<br />

observed at depths of 1,000m’. 10 <strong>The</strong> result has<br />

been changes in ocean currents, depleted oxygen<br />

zones, extinction of marine species, and shifts<br />

in growing seasons. <strong>The</strong> list goes on. All of this<br />

defies borders and yet ironically this place has also<br />

become the site of border and political conflict.<br />

As these watery bodies between bordered land<br />

masses become pathways for migrants escaping<br />

warfare and climate displacement they become<br />

graveyards; the Mediterranean alone has claimed<br />

the lives of at least 19,164 migrants since 2014. 11<br />

In another twist to this tale, these ocean graves<br />

are now battlegrounds for deep-sea mining<br />

contracts as demand for global resources pushes<br />

the focus into the ocean. <strong>The</strong> true impact on<br />

biodiversity of deep-sea mining is immeasurable;<br />

more people have walked the lunar landscape<br />

than have seen the deepest parts of the seabed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Rescue<br />

Breaking the surface I refill my lungs. <strong>The</strong> horizon<br />

appears with ocular clarity but I can’t ignore the<br />

sounds in the distance of the making and doing<br />

of this terrestrial world. I’m still craving the<br />

boundless space below the water, the muffled<br />

and unfocused rippling that occupied my mind<br />

and body. Craving the world of Melville’s whale,<br />

where many meanings and mythologies reveal<br />

themselves. <strong>The</strong> painter and poet Etel Adnan’s<br />

words flood in, ‘<strong>The</strong>re’s sea, ocean, and turbulent<br />

rivers, and there are the great lakes, matrix of<br />

storms, last refuge for mythologies, sailing ports<br />

and platforms for interstellar voyages.’ 12 She, like<br />

many artists, gives us the gift of showing the<br />

potential of aquatic thinking to break bad old<br />

habits and the dialectics that underpin them; and<br />

in many ways that is the great achievement of<br />

works exhibited in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong>.<br />

Rescuing ourselves from the disconnected tapestry<br />

that is mapped out above will require new tools<br />

and it is here where art can carefully darn and<br />

repair. <strong>The</strong> first thread is its ability to host an idea<br />

we haven’t yet articulated or we don’t see the<br />

need for. Nowhere is this more relevant than in<br />

the work of Forensic Oceanography, whose work<br />

embodies the cross-disciplinary entanglements<br />

that can make the unseen seen. <strong>The</strong>ir broader<br />

practice brings architects, artists, and forensic<br />

scientists together to ‘investigate state and<br />

corporate violence, human rights violations<br />

and environmental destruction all over the<br />

world.’ 13 <strong>The</strong> footage on view here is harrowing.<br />

<strong>The</strong> increasing human entanglement with the<br />

ocean as a passage to refuge is exposed in two<br />

Mediterranean crossings by migrants. In bringing<br />

Vertigo <strong>Sea</strong>, 2015 by John Akomfrah to Sligo the<br />

exhibition welcomes not narratives but situations,<br />

both political and ecological. <strong>The</strong>re is a powerful<br />

positioning of Akomfrah’s work as the opening<br />

piece in this exhibition. His three-screen mix<br />

seems to actualize Haraway’s fabulations, pulling<br />

wild facts and fiction together to journey through<br />

aquatic stories of whaling, colonialisation and<br />

migration. <strong>The</strong> work is intense and assaulting;<br />

there is little more to do than ‘stay in the trouble’,<br />

a second tool in reconnecting us. In commissioning<br />

9<br />

10

the composer Karen Power to produce new audio<br />

work for the show it fully commits to the nonocular.<br />

<strong>The</strong> piece, entitled no man’s land, is based<br />

on specially made field recordings that uncover<br />

the unique sonic profile of the Sligo seaboard.<br />

Power, in collaboration with soprano Michelle<br />

O’Rourke, open the exhibition with a performance<br />

immersing us in the tonality of the ocean and<br />

reconnecting us with this otherworldly sensorium.<br />

In Shaun Gladwell’s Storm Sequence, 2000<br />

Morton’s ‘strange stranger’ is evoked, with the<br />

oncoming storm as the ‘other’. <strong>The</strong> mesmerising<br />

work slowly unfolds with a skateboarder and<br />

the storm dancing together, waves rising behind<br />

him on Bondi Beach, until the storm’s intensity<br />

ends the entanglement; the rhythms of the storm<br />

become too powerful for it to continue. This<br />

feeling of otherness is evident too in Susanne M.<br />

Winterling’s work, planetary opera in three acts,<br />

divided by the currents, 2018; through sound and<br />

image she inverts the relationship between the<br />

ocean and us. We are immersed in a multi-species<br />

experience, where space becomes borderless and<br />

we co-exist with the maritime. Another tool with<br />

which to build new worlds is opened up.<br />

All the works speak on our behalf and in talking<br />

loudly, the complexity of our relationship with<br />

the sea is revealed. <strong>The</strong> works don’t stand still;<br />

they break the bad habit of viewing the ocean as<br />

something over there and in doing so reconnect<br />

us. Our terrestrial realities blur and new worlds<br />

are built. <strong>The</strong> words of Emily Dickinson flow in,<br />

‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant’. 14 <strong>The</strong>se words<br />

seem to fit this aquatic storytelling place.<br />

I break the surface one last time. Underwater<br />

shards of light shift my gaze – they cut through<br />

planes and I see things slant through the blue<br />

watery world. ‘<strong>The</strong> truth must dazzle gradually’<br />

Dickinson tells us. Glancing up from the sandy<br />

bottom the light splits and splits again.<br />

Rainbowing, it dazzles me slowly.<br />

Rosie O’Reilly, 2020<br />

Works Cited<br />

1<br />

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the trouble,<br />

Making Kin in the Chthulucene. 2016, Duke<br />

University Press. Durham and London<br />

2<br />

https://maps.biodiversityireland.ie. 28/01/2019<br />

3<br />

Ibid Haraway.<br />

4<br />

‘Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool<br />

production and engraving” https://www.nature.<br />

com/articles/nature13962. 14/02/2020<br />

5<br />

External auditory exostoses among western<br />

Eurasian late Middle and Late Pleistocene humans.<br />

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/<br />

article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0220464.<br />

14/02/2020<br />

6<br />

<strong>The</strong> Waterside Ape. BBC Radio 4 Documentary.<br />

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07v0hhm<br />

07/01/2020<br />

7<br />

Morton, Timothy. Dark Ecology. For a Logic of<br />

Future Coexistence. 2016, Columbia University<br />

Press. New York<br />

8<br />

Tiadalectics. Imagining an Oceanic Worldview<br />

through Art and Science. Edited by Stefanie<br />

Hessler. 2018. TBA21-Academy, London. <strong>The</strong> MIT<br />

Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London.<br />

9<br />

Ibid Hessler.<br />

10<br />

https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/<br />

ocean-and-climate-change. 05/12/19<br />

11<br />

https://www.iom.int/news/iom-mediterranean-<br />

arrivals-reach-110699-2019-deaths-reach-1283-<br />

world-deaths-fall. 05/02/2020<br />

12<br />

Etal Adnan. <strong>Sea</strong> and Fog. 2012, Nightboat Books,<br />

New York<br />

13<br />

https://forensic-architecture.org/about/agency.<br />

06/02/2020<br />

14<br />

<strong>The</strong> Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading<br />

Edition, <strong>The</strong> Belknap Press of Harvard University<br />

Press, 1998<br />

11<br />

12

13

John Akomfrah (b.1957)<br />

Vertigo <strong>Sea</strong>, 2015<br />

three channel HD colour video installation, 48 mins<br />

In this work, filmmaker John Akomfrah explores man’s<br />

relationship with the sea and its role in the history<br />

of slavery, migration, and conflict. A meditation on<br />

the aquatic sublime, Vertigo <strong>Sea</strong> brings together a<br />

collection of oblique tales and histories that speak to the<br />

multiple significances of the ocean and humankind’s<br />

often troubling relationship with it.<br />

With sweeping and hypnotic imagery of the aquatic and<br />

cetacean worlds, Vertigo <strong>Sea</strong> washes in waves over its<br />

audience, bringing with it the traumas, memories and<br />

the hopes of a fractured world.<br />

Touching upon migration, the history of slavery and<br />

colonisation, war and conflict and current ecological<br />

concerns, Vertigo <strong>Sea</strong> is a narrative on humankind and<br />

nature, on beauty, violence and on the precariousness of<br />

life.<br />

Shot on the Isle of Skye, the Faroe Islands and the<br />

Northern regions of Norway, and including footage<br />

from the BBC’s Natural History Unit, Vertigo <strong>Sea</strong> draws<br />

upon two remarkable books: Herman Melville’s Moby<br />

Dick (1851) and Heathcote Williams’ epic poem “Whale<br />

Nation” (1988), a harrowing and inspiring work which<br />

charts the history, intelligence and majesty of the largest<br />

mammal on earth.<br />

Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery,<br />

London.<br />

15<br />

16

17<br />

18

19<br />

20

21<br />

22

23<br />

24

25<br />

26

27<br />

28

29<br />

30

Forensic Oceanography<br />

and Forensic Architecture<br />

Forensic Oceanography is a project initiated within the<br />

Forensic Architecture agency by Charles Heller and<br />

Lorenzo Pezzani, in the wake of the Arab uprisings of<br />

2011. It seeks to critically investigate the militarised<br />

border regime imposed by European states across the<br />

EU’s maritime frontier, analysing the political, spatial<br />

and aesthetic conditions that have turned the waters<br />

of the Mediterranean <strong>Sea</strong> into a deadly liquid for the<br />

illegalised migrants seeking to cross it. <strong>The</strong> more than<br />

30,000 migrants who have died at and through the sea<br />

over the last 30 years are the victims of what Forensic<br />

Oceanography call “liquid violence”.<br />

By combining human testimonies with traces left<br />

across the digital sensorium of the sea constituted by<br />

radars, satellite imagery and vessel tracking systems,<br />

Forensic Oceanography has mobilised surveillance<br />

means ‘against the grain’ to contest both the violence<br />

of borders and the regime of (in)visibility on which it is<br />

founded.<br />

While the seas have been carved up into a complex<br />

jurisdictional space that allows states to extend their<br />

sovereign claims through police operations beyond the<br />

limits of their territory, but also to retract themselves<br />

from obligations, such as rescuing vessels in distress,<br />

Forensic Oceanography has sought to locate particular<br />

incidents within the legal architecture of the EU’s<br />

maritime frontier, so as to determine responsibility for<br />

them. Forensic Oceanography’s reports have served<br />

as the basis for several legal cases against European<br />

states.<br />

31<br />

32

Presented here is a video<br />

diptych that is part of<br />

investigations undertaken<br />

by Forensic Oceanography<br />

concerning different phases<br />

in the evolving border regime<br />

since 2011. <strong>The</strong> diptych<br />

brings together <strong>The</strong> Crime<br />

of Rescue - <strong>The</strong> Iuventa<br />

Case (2018), which offers a<br />

counter-investigation of the<br />

accusations of collusion used<br />

to justify the seizure of the<br />

rescue NGO boat Iuventa;<br />

and Mare Clausum - <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Sea</strong> Watch vs Libyan Coast<br />

Guard Case (2018), which<br />

reconstructs a confrontation<br />

event in which the Libyan<br />

coast guard attempted to<br />

intercept migrants while<br />

the rescue NGO <strong>Sea</strong> Watch<br />

sought to rescue them.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se videos, both of which<br />

have been produced in<br />

collaboration with Forensic<br />

Architecture, point to the<br />

two entangled dimensions<br />

of the strategy currently<br />

implemented by Italy and<br />

the EU to seal off the central<br />

Mediterranean route:<br />

criminalising solidarity, and<br />

outsourcing border control<br />

to the Tripoli-based Libyan<br />

government and militias.<br />

33<br />

34

35<br />

36

Forensic Oceanography<br />

and Forensic Architecture<br />

Mare Clausum – <strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> Watch vs<br />

Libyan Coast Guard Case, 2018<br />

video installation, 28 mins<br />

On the 6 November 2017, the NGO <strong>Sea</strong> Watch and<br />

the Libyan coast guard were involved in a highly<br />

confrontational event, after both were requested to<br />

rescue a boat carrying more than 130 migrants. <strong>The</strong><br />

intercepted migrants however sought to evade their<br />

fate of violence at the hands of their Libyan captors<br />

by swimming towards the rescue NGO vessels, which<br />

offered the prospect of safety in Europe instead.<br />

<strong>Sea</strong> Watch managed to recover 59 people who were<br />

brought to Italy, while 47 passengers were pulled-back<br />

to Libya, where several were subjected to grave<br />

violations. At least 20 passengers died before and<br />

during the rescue. This video reconstruction offers a<br />

striking illustration of the lethal outcomes of Italy and<br />

the EU’s policy of externalisation of border control.<br />

It is part of the “Mare Clausum” report by Forensic<br />

Oceanography, which has served as the basis for a legal<br />

complaint against Italy submitted to the European Court<br />

of Human Rights.<br />

Project team Forensic Oceanography: Charles Heller,<br />

Lorenzo Pezzani, Rossana Padeletti<br />

Project team Forensic Architecture: Stefan Laxness,<br />

Stefanos Levidis, Grace Quah, Nathan Su,<br />

Samaneh Moafi, Christina Varvia, Eyal Weizman<br />

Produced with the support of the Watch<strong>The</strong>Med<br />

platform, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the<br />

Republic and Canton of Geneva<br />

37<br />

38

Forensic Oceanography<br />

and Forensic Architecture<br />

<strong>The</strong> Crime of Rescue – <strong>The</strong> Iuventa<br />

Case, 2018<br />

video installation, 33 mins<br />

On 2 August 2017, the ship Iuventa of the German<br />

NGO Jugend Rettet (‘Youth Rescue’) was seized by the<br />

Italian judiciary under suspicion of “aiding and abetting<br />

illegal immigration” and collusion with smugglers. <strong>The</strong><br />

video presented here offers a counter-investigation of<br />

the authorities’ version of the events, and a refutation<br />

of their accusations. While the latter operate by<br />

decontextualising factual elements and recombining<br />

them into a spurious chain of events, our analysis<br />

attempts instead to cross-reference all elements of<br />

evidence into a coherent spatiotemporal model. This<br />

video has been part of the legal defence of Jugend<br />

Rettet. <strong>The</strong> Iuventa remains to this day under custody of<br />

the Italian police in the port of Trapani, Sicily.<br />

Project team Forensic Oceanography: Charles Heller,<br />

Lorenzo Pezzani, Rossana Padaletti, Richard Limeburner<br />

Project Team Forensic Architecture: Nathan Su,<br />

Christina Varvia, Eyal Weizman, Grace Quah<br />

Produced with the support of Borderline Europe, the<br />

Watch<strong>The</strong>Med platform and Transmediale<br />

39<br />

40

41<br />

42

Forensic Oceanography<br />

<strong>The</strong> European Union’s Lethal<br />

Maritime Frontier: Illegalised<br />

Migration, Bordering and Deaths at<br />

<strong>Sea</strong>, Central Mediterranean,<br />

2011–2018 (2019)<br />

vinyl timeline<br />

Presented here is a video diptych that is part of<br />

investigations undertaken by Forensic Oceanography<br />

concerning different phases in the evolving border<br />

regime since 2011. <strong>The</strong> content on each screen analyses<br />

and contests a particular mode of border violence, all<br />

the while drawing a political anatomy of the fluctuating<br />

patterns of border control and (non)assistance at<br />

sea, and their dramatic consequences for the lives of<br />

migrants. <strong>The</strong>se broad trends are here summarised in a<br />

timeline.<br />

Project team: Charles Heller, Lorenzo Pezzani,<br />

Gian-Andrea Monsch, Bob Trafford, Robert Preusse<br />

Courtesy Forensic Oceanography and Forensic<br />

Architecture.<br />

43<br />

44

45<br />

46

Shaun Gladwell (b.1972)<br />

Storm Sequence, 2000<br />

single channel digital video, colour, sound, 8 mins<br />

Shaun Gladwell is an Australian contemporary artist<br />

who works predominantly in video and performance.<br />

His works are shot within natural and urban<br />

environments, and explore the relationship between<br />

landscapes and people while simultaneously drawing<br />

deeply from art and literary history.<br />

Storm Sequence is a deceptively simple work. It depicts<br />

the solitary action of a skateboarder – the artist, Shaun<br />

Gladwell – freestyling on the edge of a concrete drop<br />

in front of the ocean at Bondi Beach in Sydney. <strong>The</strong><br />

camera hardly moves and concentrates only on his<br />

movements, as he pirouettes and spins. Incorporating<br />

an organic, liquid-like soundtrack by Sydney composer<br />

Kazumichi Grime, the footage is presented at a reduced<br />

framerate to give the illusion of slow motion. Movement<br />

which in real time would have a jerky rhythm becomes<br />

graceful, emphasising the relationship between the<br />

individual, the ocean and the oncoming storm.<br />

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.<br />

47<br />

48

49<br />

50

51<br />

52

53<br />

54

Karen Power (b. 1977)<br />

no man’s land, 2020<br />

eight channel audio installation, 40mins<br />

no man’s land is a multifunctional composition<br />

presented as both an eight channel sound installation<br />

and a live performance for voice and composed field<br />

recordings, all of which lie in conversation with the<br />

major surrounding artworks of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong>.<br />

This entire composition is based on Power’s field<br />

recordings of the sea from many locations, including<br />

new site-specific recordings made throughout Sligo’s<br />

waterways over the six-month period of this project.<br />

Subtle additions to the installation had being planned,<br />

mapping local and seasonal sea changes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> concept and structure of this sound installation<br />

emulates the living and ever-changing state of our<br />

ocean, as simultaneously constant and fleeting, fragile<br />

and robust, volatile and calm, while at the same time<br />

being mesmerising, beautiful, alluring, harsh, and<br />

encompassing all of life and death.<br />

Courtesy the artist, supported by the Arts Council<br />

Music Project Awards.<br />

55<br />

56

57<br />

58

59<br />

60

61<br />

62

63<br />

64

Susanne M. Winterling (b.1971)<br />

planetary opera in three acts, divided<br />

by the currents, 2018<br />

12 channel sound installation, 7 mins<br />

planetary loop of gravitation, 2018<br />

4K projection mapping, 7 mins<br />

flags of the miracular (welcome to<br />

the algae empire), 2018<br />

textile, bamboo<br />

planetary opera in three acts, divided by the currents<br />

is a composition of natural and synthetic, as well<br />

as documentary and imaginary sounds, including<br />

hydrophone recordings of algae, the sound of green<br />

turtles hatching, crabs rubbing their claws together and<br />

other ecological marvels. <strong>The</strong> opera is accompanied by<br />

planetary loop of gravitation, and flags of the miracular<br />

(welcome to the algae empire), both 2018. <strong>The</strong>se works<br />

immerse the spectator in a field of floating particles<br />

- at once reminiscent of the sky, the deep sea, and<br />

interplanetary space - as gargantuan algae whirl and<br />

dance around them.<br />

65<br />

66

<strong>The</strong>se pieces enact a sensory<br />

inversion of the dominant<br />

anthropocentric logics<br />

which govern our awareness<br />

through their dramatic<br />

reversals of scale and focus,<br />

deploying historical forms<br />

of media usually associated<br />

with the internal drama<br />

of humankind, to instead<br />

express the drama of the<br />

planet. Participants are<br />

immersed within a grand<br />

marine imaginary which<br />

aims to generate a new sense<br />

of interspecies alliance with<br />

the creatures that dwell<br />

within planetary space and<br />

through the currents.<br />

Courtesy the artist and<br />

Empty Gallery, supported by<br />

the Goethe Institut Irland.<br />

67<br />

68

69<br />

70

Cover: Susanne M. Winterling, planetary opera in three acts, divided by the currents, 2018.<br />

12-channel sound installation. planetary loop of gravitation, 2018. Computer generated imagery<br />

mapped projection for curved screen 4K, 9 min. Photo: Michael Yu. Courtesy the artist and Empty<br />

Gallery.<br />

71<br />

72

73<br />

74

75<br />

76

77<br />

78

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Around</strong> <strong>Us</strong><br />

John Akomfrah (GH/GB), Forensic Oceanography and Forensic<br />

Architecture (GB), Shaun Gladwell (AU), Karen Power (IE),<br />

Susanne M. Winterling (DE).<br />

Curated by Emer McGarry<br />

<strong>The</strong> Model; home of <strong>The</strong> Niland Collection<br />

29 Feb. – 31 May 2020<br />

Publication design<br />

Concepta Boyce<br />

Image credits<br />

Installation Shots<br />

Heike Thiele, Daniel Paul McDonald and Barry McHugh<br />

John Akomfrah<br />

© Smoking Dogs Films, courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson<br />

Gallery<br />

Forensic Oceanography and Forensic Architecture<br />

© Forensic Oceanography and Forensic Architecture<br />

Shaun Gladwell<br />

© Shaun Gladwell, courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery<br />

Karen Power<br />

Page 57, images by John Godfrey<br />

Susanne M. Winterling<br />

© Susanne M. Winterling, images by Michael Yu, courtesy the artist<br />

and Empty Gallery<br />

This exhibition is sponsored by Hazelwood House, Sligo.<br />

With additional support from Goethe Institut Irland, Ecclesiastical Insurance and Arts<br />

Council Music Project Award.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Model; home of <strong>The</strong> Niland Collection<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mall, Sligo | (071) 9141405 | themodel.ie<br />

Registered Charity No. CHY 12212<br />

79<br />

80

81