Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Lane 1: Performance<br />

Multisystems, Overload, Adaptation Oh My!<br />

Get Faster with a Plan<br />

by Kevin Balance<br />

Last issue we talked about periodization<br />

and the need for a plan. This<br />

month’s article builds upon that concept<br />

and takes a deeper look into the<br />

contents of our mesocycle’s (4-6 week<br />

period) design. Let’s start with the<br />

different body systems we need to<br />

train.<br />

The Energy System. Ever hear of<br />

ATP? How about adenosine triphosphate?<br />

Don’t worry about that. All<br />

you need to know is that ATP is the<br />

energy source that allows muscles to<br />

both work and recover. For long distance<br />

runners, the more efficient our<br />

energy system is the better.<br />

The Neuromuscular System. If<br />

you’re a car, this is your battery.<br />

We’re talking about the nerve firing<br />

system. One of the main functions of<br />

the nervous system is to send messages<br />

to the muscles and surrounding<br />

tissues. Better have that trained well,<br />

especially when it comes to developing<br />

speed and power because it’s the<br />

most important system for sprinting in<br />

your finishing kick.<br />

The Musculoskeletal System. This<br />

system is responsible for producing<br />

force via muscle tissues. Those muscle<br />

tissues transmit force to bones and<br />

other such things that propel your<br />

body forward. Skeletal muscles, fascia,<br />

bones, joints, connective tissues:<br />

all these make up the musculoskeletal<br />

system.<br />

Even though the Energy System is the<br />

most important of the three for us runners,<br />

all of them are important and<br />

interdependent on one another. We<br />

have to train all of them—not just the<br />

Energy System—whether we like it or<br />

not. If we ignore one for the other,<br />

then that system of focus will hit a<br />

glass ceiling. Your progress will be<br />

stymied because the other two components<br />

will be holding you back.<br />

Running is supposed to be simple,<br />

right? Just put one foot in front of the<br />

other and go for as long and fast as<br />

you can. Having just reread over my<br />

first few paragraphs ( I’m the damn<br />

editor of this rag; I better proofread—<br />

still pisses me off how many “typos” I<br />

miss), I think things are getting a little<br />

too complicated. Let’s look at it another<br />

way. I think most of us get that<br />

If we just do the same runs<br />

and workouts week after<br />

week, our bodies will cease<br />

to adapt, cease to improve.<br />

we can’t do the same workout every<br />

day. Some days we go easy, some<br />

days we’re at the track, others still we<br />

practice at lactate threshold pace, and<br />

every weekend we go long. We’re<br />

training various biomotor components.<br />

Let’s put a name to each one.<br />

Endurance. We’re talking work capacity.<br />

Our ability to hold off fatigue.<br />

Progression runs, threshold runs,<br />

longer intervals (Kara Molloy Haas<br />

does 5 x 5K!) are just a couple of ways<br />

to improve endurance. We all need a<br />

high work capacity because that is<br />

what allows us to train harder and better<br />

for longer amounts of time. Somebody<br />

who can only run for 30 minutes<br />

doesn’t have nearly as much endurance<br />

as someone who can trek for 60.<br />

Strength. That’s your ability to produce<br />

force. For example, many runners<br />

do hill workouts as a means to<br />

improve strength.<br />

Speed. Yes, we all know: moving with<br />

celerity, as quickly as we can. Sprinting.<br />

We do short intervals (400s,<br />

200s, 100s) on the track or other such<br />

place to improve our speed.<br />

Now that we have put names to some<br />

of the different physiological components<br />

that we need to train, we can<br />

concentrate on how to improve them.<br />

The chief way to improve a particular<br />

facet of your training is to overload it.<br />

You have to fatigue your body to improve<br />

it. We must create training scenarios<br />

that push our bodies beyond<br />

their accustomed limits if we want to<br />

lower our PRs. Of course, it is nonsensical<br />

to train this way in every session,<br />

but you certainly need to overload<br />

your body once or twice every microcycle<br />

(7-10 day period).<br />

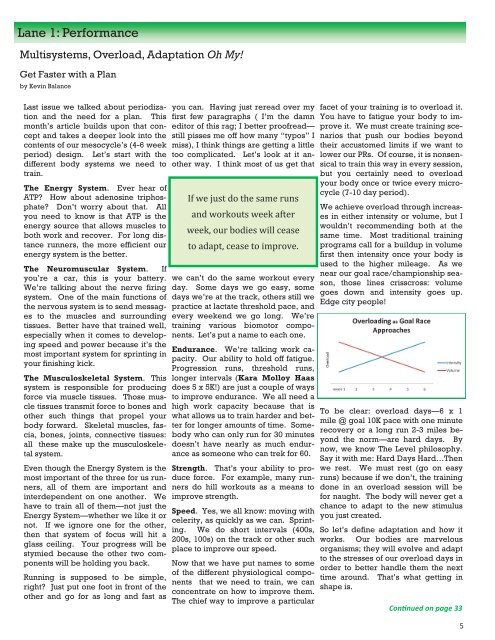

We achieve overload through increases<br />

in either intensity or volume, but I<br />

wouldn’t recommending both at the<br />

same time. Most traditional training<br />

programs call for a buildup in volume<br />

first then intensity once your body is<br />

used to the higher mileage. As we<br />

near our goal race/championship season,<br />

those lines crisscross: volume<br />

goes down and intensity goes up.<br />

Edge city people!<br />

To be clear: overload days—6 x 1<br />

mile @ goal 10K pace with one minute<br />

recovery or a long run 2-3 miles beyond<br />

the norm—are hard days. By<br />

now, we know The <strong>Level</strong> philosophy.<br />

Say it with me: Hard Days Hard…Then<br />

we rest. We must rest (go on easy<br />

runs) because if we don’t, the training<br />

done in an overload session will be<br />

for naught. The body will never get a<br />

chance to adapt to the new stimulus<br />

you just created.<br />

So let’s define adaptation and how it<br />

works. Our bodies are marvelous<br />

organisms; they will evolve and adapt<br />

to the stresses of our overload days in<br />

order to better handle them the next<br />

time around. That’s what getting in<br />

shape is.<br />

Continued on page 33<br />

5