LWRS June 2020 Volume 1, Issue 1

Inaugural Issue co-edited by Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa and Isabel Baca

Inaugural Issue co-edited by Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa and Isabel Baca

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Inaugural <strong>Issue</strong>: Recovery and Transformation<br />

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

Special Guest Editors<br />

Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

Isabel Baca<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>Issue</strong> 1 <strong>June</strong> <strong>2020</strong>

Latinx Writing and<br />

Rhetoric Studies<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>Issue</strong> 1 <strong>June</strong> <strong>2020</strong><br />

Senior Editor: Iris D. Ruiz<br />

Special Guest Editors: Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

Isabel Baca<br />

Production Editor: Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

Copy Editors: Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

Isabel Baca<br />

Editorial Board: Sara P. Alvarez, Queens College, CUNY<br />

Damián P. Baca, University of Arizona<br />

Isabel Baca, University of Texas at El Paso<br />

Christina Cedillo, University of Houston – Clear Lake<br />

Candace de León-Zepeda, Our Lady of the Lake University<br />

Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa, Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi<br />

Cruz Medina, Santa Clara University<br />

Jaime Armin Mejía, Texas State University<br />

Iris D. Ruiz, University of California, Merced<br />

Raúl Sánchez, University of Florida<br />

Helen Sandoval, University of California, Merced<br />

Jasmine Villa, East Stroudsburg University

Journal of the NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus<br />

ISSN 2687-7198<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly<br />

journal published and supported by the NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Articles are<br />

published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-<br />

Noncommercial-NoDerivs). Some material is used with permission.<br />

Copyright © <strong>2020</strong> <strong>LWRS</strong> Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and<br />

contributors.<br />

Publication website – https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com<br />

Permissions: All materials contained in this publication are property of <strong>LWRS</strong><br />

Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and contributors. No parts of this<br />

publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher<br />

and/or contributors.<br />

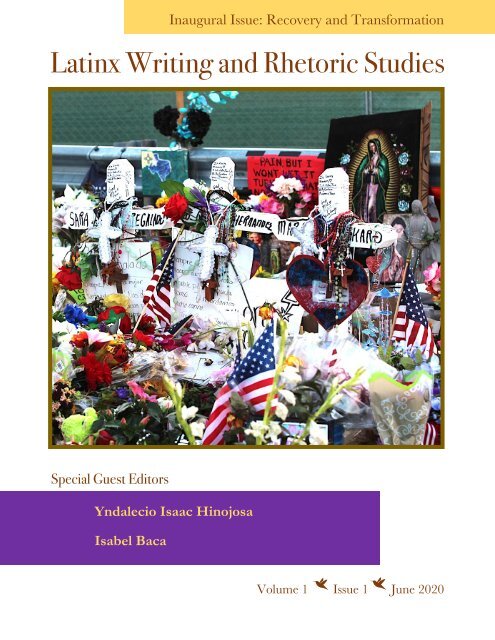

Journal Cover: The crosses for the victims flowed with flowers that visitors watered<br />

consistently until the memorial was moved to Ponder Park. Photo taken by Antonio<br />

Villaseñor-Baca. Villaseñor-Baca (he/they) is a Xicanx bilingual multimedia journalist,<br />

photographer, and poet/writer. Born in the Sun City of El Paso, TX and on the border<br />

with Ciudad Juárez, he spends all his time listening to records and going to concerts.<br />

He has 16 tattoos, his favorite of which are of Chilean musician Mon Laferte and one<br />

of an axolotl- his favorite animal. He is currently pursuing his MFA in creative writing<br />

at the University of Texas at El Paso where is also a professor in the FYC program at<br />

UTEP. He has his own music magazine titled Con Safos, is the online editor for Minero<br />

Magazine, writes for YR Media, and has bylines in El Paso Inc. and Borderzine.com.<br />

Accurately reporting on the border is a priority for him because of the constant<br />

misnarratives about his hometowns. Other images captured by Villaseñor-Baca will<br />

appear throughout this issue.<br />

This issue also features photographs taken by Gaby Velasquez.<br />

See article by Elvira Carrizal-Dukes in this issue for more information on Velasquez.

Special Guest Editor Bios<br />

Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa is an Assistant Professor of English at Texas A&M<br />

University-Corpus Christi and co-editor of Open Words: Access and English Studies, a<br />

refereed scholarly journal. His scholarly contributions focus on the intersections<br />

between Chicana feminist theory and Writing Studies under the lenses of border<br />

theory, gender, sexuality, and race. His most recent work is Bordered Writers: Latinx<br />

Identities and Literacy Practices at Hispanic-Serving Institutions, a co-edited collection (with<br />

Isabel Baca and Susan Wolff Murphy) of testimonios and scholarly articles that<br />

examine innovated writing pedagogies and the experiences of Latinx student writers<br />

at Hispanic-Serving Institutions nationwide. Other related published works include:<br />

“Localizing the Body for Practitioners in Writing Studies” in El Mundo Zurdo 5 and<br />

“The Coyolxauhqui Imperative in Developing Comunidad-Situated Writing Curricula<br />

at Hispanic-Serving Institutions,” co-authored with Candance de Leon-Zepeda in El<br />

Mundo Zurdo 6. He is the recipient of the <strong>2020</strong> Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi<br />

University’s Excellence in Research and Scholarly Activity Award.<br />

Isabel Baca is Associate Professor of English, Director of the Community Writing<br />

Partners Program, and Director of the Bilingual Professional Writing Certificate<br />

Program at the University of Texas at El Paso. She is co-editor (with Yndalecio Isaac<br />

Hinojosa and Susan Wolff Murphy) of Bordered Writers: Latinx Identities and Literacy<br />

Practices at Hispanic-Serving Institutions. She edited also Service-Learning and Writing: Paving<br />

the way for Literacy(ies) through Community Engagement (2012) and Borders (2011). She is a<br />

2017 University of Texas System Regents’ Outstanding Teaching Award recipient and<br />

a 2018 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Humanities Initiatives at<br />

Presidentially Designated Institutions Grant recipient. Her research interests include<br />

service-learning in writing studies, bilingual professional writing, second-language<br />

writers, and community engagement in higher education.<br />

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is the professional journal for the college scholarteacher<br />

interested in both national and international literacy events dealing with Latinx<br />

Communities, Diaspora, and Identity and Cultural Practices. <strong>LWRS</strong> publishes articles<br />

about literature, rhetoric-composition, critical theory, creative writing theory and<br />

pedagogy, linguistics, literacy, reading theory, pedagogy, and professional issues related<br />

to the teaching and creation of Latinx epistemologies. <strong>Issue</strong>s may also include review<br />

essays. Contributions may work across traditional field boundaries; authors represent<br />

the full range of institutional types.

Photographs – 2019 El Paso, Texas mass shooting memorial at Walmart<br />

Photo by Antonio Villaseñor-Baca<br />

A signed Walmart uniform hangs on the Gateway West among the makeshift<br />

memorial in El Paso, Texas outside of the Walmart.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | vi

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

CONTENTS <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>Issue</strong> 1 <strong>June</strong> <strong>2020</strong><br />

1 Editor’s Introduction: Honoring our Past, Living our Present, and<br />

Fighting for our Future – La Lucha Sigue<br />

Isabel Baca and Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

11 The Fourth Movement: Founder’s Letter for Latinx Writing and Rhetoric<br />

Studies<br />

Iris D. Ruiz<br />

19 Rhetorics of Translation in Tino Villanueva’s Cronica de mis años perores<br />

(Chronicle of My Worst Years)<br />

Aydé Enríquez-Loya<br />

49 Interview with the El Paso Strong Mural Artist Gabe Vasquez<br />

Elvira Carrizal-Dukes<br />

57 Pardon My Acento: Racioalphabet Ideologies and Rhetorical Recovery<br />

through Alternative Writing Systems<br />

Kelly Medina-López<br />

81 Mexican Food, Assimilation, and Middle-Class Mexican Americans or<br />

Chicanx<br />

Jaime Armin Mejía<br />

97 Inventing PLEA: A Social History of a College-Writing Initiative at a<br />

Chilean University<br />

Ana M. Cortés Lagos

121 Cont. Interview with the El Paso Strong Mural Artist Gabe Vasquez<br />

Elvira Carrizal-Dukes<br />

127 Poets in the Classroom: What We Do When We Teach Writing<br />

Laurie Ann Guerrero, with<br />

Sabrina San Miguel and Cecilia Amanda Macias<br />

135 Always Been “Inside”<br />

J. Paul Padilla<br />

161 Rhetorical Herencia: Writing Toward a Theory of Rhetorical Recovery and<br />

Transformation<br />

Cristina D. Ramírez<br />

179 Cont. Interview with the El Paso Strong Mural Artist Gabe Vasquez<br />

Elvira Carrizal-Dukes<br />

185 Review of Bordered Writers: Latinx Identities and Literacy Practices at Hispanic-<br />

Serving Institutions<br />

Juan C. Guerra<br />

191 Review of Brokering Tareas: Mexican Immigrant Families Translanguaging<br />

Homework Literacies<br />

Marlene Galván<br />

196 Call for Submissions

Photographs – 2019 El Paso, Texas mass shooting memorial at Walmart<br />

Photo by Gaby Velasquez<br />

People gather outside the Walmart where the mass shooting took place<br />

and begin to place items to memorialize the victims.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | ix

Photographs – 2019 El Paso, Texas mass shooting memorial at Walmart<br />

Photo by Gaby Velasquez<br />

Woman brings a carnation for the memorial developing outside of the Walmart.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | x

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

Vol. 1, No. 1, <strong>June</strong> <strong>2020</strong>, 1–9<br />

Editor’s Introduction: Honoring our Past, Living our Present,<br />

and Fighting for our Future – La Lucha Sigue<br />

Isabel Baca<br />

University of Texas at El Paso, on land of the Tigua and Mescalero people. 1<br />

Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi, on land of the Karankawan people. 2<br />

De nuestra gente, con nuestra gente y para la gente.<br />

We proudly introduce Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies (<strong>LWRS</strong>), a refereed<br />

academic journal sponsored by the NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Founded by then<br />

caucus co-chair Iris D. Ruiz, <strong>LWRS</strong> will play an integral part for enacting the vision<br />

and mission of the NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. <strong>LWRS</strong> is a venue to “exchange<br />

ideas,” a repository of information to “serve as a resource for members, the<br />

educational community and the general public,” and a network of writers to “support<br />

activities that promote the learning and advancement of students and teachers of<br />

color” (Latinx caucus, p. 1). Our platform is meant for the scholar-teacher (and we<br />

might add scholar-activist) whose interests include writing or rhetoric studies that<br />

center on Latinx communities, diaspora, identity, and cultural practices. As editors of<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, our primary goal will be to provide readers with a robust multimodal and<br />

dynamic publication that features articles about literature, rhetoric-composition,<br />

critical theory, creative writing theory, reading theory, border theory, applied<br />

linguistics, literacy, and professional issues related to the teaching and creation of<br />

Latinx epistemologies. To achieve this goal, we aim to publish authors and scholars<br />

that represent the full range of institutional types through their intellectual and<br />

community labor and whose contributions to <strong>LWRS</strong> will transcend the traditional<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies ISSN 2687-7198<br />

https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly journal published and supported by the<br />

NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Articles are published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-<br />

Noncommercial-NoDerivs) ISSN 2687-7198. Copyright © <strong>2020</strong> <strong>LWRS</strong> Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and<br />

contributors. Some material is used with permission.

Isabel Baca and Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

boundaries of our disciplines to offer not only new knowledge but also shape existing<br />

knowledge.<br />

Indeed, it has been an honor to serve as the first guest editors for this inaugural<br />

issue, an issue we themed on recovery and transformation. Recovery as a way to make<br />

visible what may have been lost, and transformation to lead us into what may lie ahead<br />

for us all. From the moment we were appointed as editors, we strived to bring forth<br />

an issue that would embody the beauty of the diverse cultures and languages that make<br />

up Latinx peoples. Yes, we would like to place an emphasis on the plurality and diversity<br />

that is Latinx. At the same time, we also wanted to demonstrate the challenges that<br />

we, as Latinx, continue to face and the individual and collaborative efforts de nuestra<br />

lucha in and outside academia as well as in our respective fields of study. We made a<br />

commitment to one another to establish <strong>LWRS</strong> as an instrument that could carve out<br />

a new discursive space, where the places made within that space are done so by nuestra<br />

gente, con nuestra gente y para la gente. We envisioned <strong>LWRS</strong> to serve as national and<br />

international voices that could cut across disciplinary and geopolitical borders. For this<br />

issue, we felt that the contributions selected will add, through forms of recovery and<br />

transformation, to our Latinx history, experience, and identity; for the range and depth<br />

of each piece speaks to the heart, spirit, and intellectual vigor of our gente and of our<br />

work as editors.<br />

Our Work as Editors<br />

There’s work to be done for our profession, for people of color in our profession and in our<br />

classrooms, work to be done for Latinos.<br />

– Victor Villanueva, Jr.<br />

In 2018, we began our work to produce the first issue of <strong>LWRS</strong>, but we must<br />

acknowledge that this work is built upon the work of others in our community. <strong>LWRS</strong><br />

extends a legacy that first began with the Capirotada newsletter, founded and first edited<br />

by Alfredo Celedon Lujan for NCTE’s Latino Caucus. Published in the summer of<br />

1994, this first newsletter, made as a one-page trifold, featured a column by then caucus<br />

co-chair Victor Villanueva Jr. 3 In his column, Villanueva calls us to action: “[t]here’s<br />

work to be done…”. Cecilia Rodriquez Milanes, who was later charged with producing<br />

and editing the newsletter, told us that Capirotada was “important work,” important<br />

because it “gave folks who couldn’t make it to the conferences a sense of ‘who we<br />

were,’” an expression she directly tied back to Lujan’s “¿Quién somos?” question that<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 2

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

he first posed to readers in that first newsletter. Now, almost twenty-five years later,<br />

as editors we recognized that there is still much more “work to be done” as Villanueva<br />

put it back then, and that that work can begin by designating <strong>LWRS</strong> as a discursive<br />

space where we as Latinx can express and define quién somos on our own terms. So,<br />

we set out to form <strong>LWRS</strong> in ways that can support our profession, our people of<br />

color, and our gente.<br />

To begin, we were charged by Senior Editor Iris D. Ruiz to develop and create<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong> for our rhetoric and composition / writing studies profession, and to do so<br />

with the vision and mission of the NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus in mind. This meant<br />

that we needed to ensure <strong>LWRS</strong> was a refereed academic publication, first and<br />

foremost. We needed a publication that would serve not only as a venue to exchange<br />

ideas but also as a resource for learning and as a vehicle that could provide<br />

opportunities for our Latinx caucus members to advance, both in their profession or<br />

comunidades. So, with that in mind, we set out to produce the first issue and sent out<br />

a call for submissions to various listservs, including our own Latinx caucus listserv, on<br />

January 24, 2019. 4 In our call for submissions, we asked contributors to consider the<br />

following questions:<br />

1. What do transformative modes of leadership look like for Latinx, our gente?<br />

2. What are possible transformative pedagogies that can be effective when<br />

teaching Latinx populations?<br />

3. What transformative modes of engagement best serve or embrace<br />

interconnectivity for identity formation, theorizing, or social change?<br />

4. In terms of recovery, how can activism play a role for Latinx communities?<br />

5. What cultural or pedagogical practices aid rhetorical recovery?<br />

6. How can Latinx develop rhetorical concepts or approaches in and out of the<br />

classroom to account for rhetors who are excluded from traditional rhetoric?<br />

We received numerous submissions by our March 25, 2019 deadline, and we called<br />

then upon the <strong>LWRS</strong> Editorial Board to blindly review submissions. 5 For further<br />

assistance and where appropriate expertise was necessary, we sent other submissions<br />

to the Editorial Board of Open Words: Access and English Studies, a refereed publication<br />

co-edited also by Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa (with Sue Hum and Kristina Gutierrez).<br />

When it came to the peer review process, we made it our priority to break away from<br />

what seems to be the norm in publication processes, oppressive methodologies in<br />

the rituals and editorial practices found throughout the profession. To set us apart,<br />

we set a priority to offer <strong>LWRS</strong> contributors something we felt publication processes<br />

within the field lacked, mentorship.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 3

Isabel Baca and Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

As editors, we set into place editorial practices for mentoring writers,<br />

especially young scholars – young Latinx scholars emerging in the field. First, we<br />

voiced our goal to mentor writers in our invitation to peer-reviewers: “Part of our<br />

mission as co-editors at <strong>LWRS</strong> is to provide mentorship, especially if a manuscript<br />

has the potential to make a significant contribution to the field, so we encourage not<br />

only constructive but also ‘productive’ feedback in ways that can strengthen<br />

manuscripts.” 5 In the review process, we called for productive feedback from our<br />

reviewers. Often, as is the case with blind reviews, criticism and/or constructive<br />

comments over the work may leave authors with little to no clear path on how best<br />

to strengthen their work. To solicit productive feedback from reviewers is to ask<br />

reviewers to go above and beyond and provide ways for how best authors can<br />

improve their manuscripts. Second, we performed additional editorial reviews after<br />

authors submitted revised manuscripts that underwent a revise and resubmit process.<br />

That means that any contribution to <strong>LWRS</strong> will go through at least four reviews: two<br />

blind reviews and two editor reviews. During our editorial reviews, we reached out to<br />

several authors to discuss the status of the manuscript, options for making the work<br />

more accessible to readers, thoughts on how best to further strengthen areas, and/or<br />

the significance of their contribution to <strong>LWRS</strong>, especially for our Latinx audience.<br />

Thus, in most cases, our editorial review called for an additional set of revisions.<br />

Some minor. Some major. But all revisions performed were done so as part of our<br />

process to work with our contributors closely. Together, we engaged in mentored<br />

writing.<br />

We learned early on that mentoring writers also required providing writers<br />

with resources, especially if those resources were to play an instrumental role to<br />

further develop the quality of submissions. So, as editors, we extended our editorial<br />

practices to include, at times, supportive measures, such as intellectual labor in<br />

locating resources and expenditures at our own expense. These measures were, in a<br />

small way, our opportunity to support scholars, especially scholars of color in our<br />

profession. When institutional and financial support is limited, as one of our<br />

contributors put it, that limitation can be “another barrier of research” for scholars<br />

of color. To aid contributors, when necessary, we provided much needed resources<br />

at the direction of our reviewers’ comments or our editorial feedback. We sent<br />

various books to some of our contributors (when access or resources to that material<br />

was limited) directly from Amazon.com or other web ordering services. In addition<br />

to books, we sent book chapters or articles in PDF to some of our contributors too.<br />

Our supportive measures took place not only to provide access to such material but<br />

also to strengthen our contributors’ arguments or to connect their work further with<br />

current scholarship in the field.<br />

Lastly, as previously mentioned, <strong>LWRS</strong> carves out a new discursive space in<br />

our profession, but to support that space, we need to align that space with structures<br />

that promote success and retention for scholars of color in our profession, especially<br />

in terms of promotion and tenure. We met several times with founder Iris D. Ruiz to<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 4

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

discuss how (in moving forward) this journal could offer our gente<br />

acknowledgement, accomplishment, and advancement. Our discussions led us to<br />

consider several ways on how to meet these goals.<br />

First, we placed land acknowledgements into the design of our publication.<br />

All institutional affiliations associated with contributors are designated a land<br />

acknowledgement. The acknowledgements serve to remind readers of our ongoing<br />

responsibilities to the Indigenous peoples of these lands. As editors, we recognize<br />

the criticisms and the performativity engendered by this practice, but in the end, such<br />

acknowledgements as our practice provide readers the opportunity to be unsettled or<br />

disrupted to know that la lucha sigue.<br />

Second, we committed to develop <strong>LWRS</strong> into a top tier journal in the field.<br />

We applied for an International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) designation with the<br />

Library of Congress. Our designation helps to acknowledge <strong>LWRS</strong> as an official<br />

academic publication on record. The ISSN distinguishes this publication from other<br />

publications and records our issues with the Library of Congress. In addition to our<br />

official status, we hope that our laborious review process and our editorial practices<br />

(all aimed at providing support and mentorship in the publication process) pave the<br />

path forward to establish <strong>LWRS</strong> as the sought-out venue to publish. We want<br />

practitioners and scholars in our field to recognize <strong>LWRS</strong> publications as noteworthy<br />

contributions to the field and/or vigorous accomplishments from our contributors.<br />

Third, we decided to organize the editorial management structure in such a<br />

way to provide editorial mentorship and extend the professionalization merits de<br />

nuestra gente. Much like the work that began with Capirotada, our work at <strong>LWRS</strong> is a<br />

community effort, and such work is done so in the spirit of helping to advance our<br />

communities. At <strong>LWRS</strong>, Senior Editors will administrate and oversee the journal and<br />

provide a final review of copy for publication. Procedures for soliciting submissions,<br />

assigning blind peer-reviews, conducting editorial reviews, and producing annual<br />

issues shall fall to our appointed Guest Editors. On a two-year appointment, our<br />

Guest Editors are charged with the responsibility, production, and release of two<br />

consecutive issues. We will stagger their appointment schedule so that there is a oneyear<br />

overlap between editors. The benefit for this overlap is twofold: (1) to maintain<br />

a level of congruency in our editorial practices and in our issues and (2) to establish a<br />

rotation where the incumbent guest editor mentors the newly appointed guest editor<br />

throughout the publication processes. Whereas Senior Editors are accredited with<br />

service to the profession in academia, appointed Guest editors are accredited with<br />

the publication of an edited journal issue. Our management structure offers Guest<br />

Editors not only mentorship in editorial work for <strong>LWRS</strong> but also activity in scholarly<br />

work for promotion and tenure. In some small way, this journal and its editors and<br />

contributors encompass altogether the work to be done for Latinx.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 5

Isabel Baca and Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

Our Contributors’ Work in this <strong>Issue</strong><br />

We are excited to present the <strong>2020</strong> inaugural issue of Latinx Writing and Rhetoric<br />

Studies (<strong>LWRS</strong>), and we are grateful for the scholars, practitioners, students, poets and<br />

artists who contributed scholarship or creative work that centered on recovery and<br />

transformation themes. A letter from Iris D. Ruiz, founder of the <strong>LWRS</strong> journal and<br />

long-time member and former co-chair of the NCTE/CCC Latinx Caucus, opens our<br />

issue. In her letter, Ruiz reminds us of the importance of self-representing and<br />

advocating for publication venues within the field of Rhetoric and Composition. With<br />

the publication of this issue, we are closer to this goal, closer to a transformative<br />

change.<br />

Throughout the pages in this issue, you will find images by photographers<br />

Antonio Villaseῆor-Baca and Gaby Velasquez. These images depict the memorial<br />

honoring the victims (listed below) from the Walmart mass shooting in El Paso, Texas<br />

on August 3, 2019.<br />

Jordan Anchondo<br />

Andre Anchondo<br />

Arturo Benavides<br />

Jorge Calvillo García<br />

Leo Campos<br />

Maribel Hernandez<br />

Adolfo Cerros Hernández<br />

Sara Esther Regalado<br />

Angelina Englisbee<br />

Raul Flores<br />

Maria Flores<br />

Guillermo “Memo” Garcia<br />

Alexander Gerhard Hoffmann<br />

David Johnson<br />

Luis Juarez<br />

Maria Eugenia Legarreta<br />

Ivan Filiberto Manzano<br />

Gloria Irma Márquez<br />

Elsa Mendoza<br />

Margie Reckard<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 6

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

Javier Amir Rodriquez<br />

Teresa Sanchez<br />

Juan de Dios Velázquez<br />

The Walmart shooting in El Paso urged us to address this tragedy. We witnessed how<br />

it brought our gente together; how it transformed a border community; and how<br />

together people worked toward recovery, an ongoing process and journey. In addition<br />

to the images, the article “Interview with El Paso Strong Mural Artist Gabe Vasquez”<br />

provides readers excerpts (both in texts and video form) from an interview with Gabe<br />

Vasquez. Vasquez, the artist responsible for creating the El Paso Strong mural, was<br />

interviewed by Elvira Carrizal-Dukes, who recounts her lived experience of that day<br />

as she discusses and presents her interview with the artist. We hope the images and<br />

excerpts allow you, as reader, to pause and reflect on recovery and transformation as<br />

you read longer articles found in this issue.<br />

For this issue, our lead article, “Rhetorics of Translation in Tino Villanueva’s<br />

Cronica de mis aῆos peores (Chronicle of My Worst Years),” is by Aydé Enríquez-Loya. By<br />

examining translations, including her own, Enríquez-Loya recovers Villanueva’s work<br />

and demonstrates how this work becomes a story suppressed by translation informed<br />

from various influences, such as migrant worker history or her own background as a<br />

Texas Chicana. What her examination shows is that translations are a reinterpretation<br />

of a text filtered through a translator’s ideological, rhetorical, and cultural<br />

understandings.<br />

Next, we present work by Kelly Medina-López, who exposes the Western<br />

colonial alphabet as a sustained and systematic technology of colonial oppression in<br />

“Pardon My Acento: Racioalphabetic Ideologies and Rhetorical Recovery through<br />

Alternative Writing Systems.” By using testimonio to support her argument, Medina-<br />

López explores processes of naming and disnaming and proposes using alternative<br />

writing systems to provide a method for reclaiming agency and autonomy. She calls<br />

on readers to consider alternative writing systems as a tool for marking difference. To<br />

underscore her argument, she utilizes emoticons throughout the text to engage and<br />

exemplify an alternative writing system.<br />

Found also in this issue is Jaime Armin Mejía, who offers his essay titled<br />

“Mexican Food, Assimilation, and Middle-Class Mexican Americans or Chicanxs.” In<br />

this essay, Mejía addresses the field of Rhetoric and Composition by exploring how<br />

teaching a course on Mexican food may allow us to address many of the rhetorical<br />

dimensions we use in our writing classes. In his essay, Mejía simultaneously highlights<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 7

Isabel Baca and Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa<br />

the deeply rooted issues of assimilation and our identities as middle-class Mexican<br />

Americans or Chicanxs.<br />

Addressing a college-writing initiative, doctoral student Ana M. Cortés Lagos<br />

describes the creation and development of a first writing program in a Chilean<br />

university in her article, “Inventing PLEA. A Social History of a College-Writing<br />

Initiative at a Chilean University.” Her work is of significance because she stresses the<br />

importance and necessity of historicizing projects like this in order for local traditions<br />

to develop disciplinary awareness and enter a dialogue with other writing studies<br />

traditions on a global scale.<br />

“Poets in the Classroom: What We Do When We Teach Writing” features<br />

Laurie Ann Guerrero, with students Sabrina San Miguel and Cecilia Amanda Macias.<br />

Guerrero held consecutive positions as Poet Laureate of the city of San Antonio (2014-<br />

2016) and the State of Texas (2016-2017). In the spirit of reaching out to the<br />

community, Guerrero, the Writer-in-Residence at Texas A&M University-San<br />

Antonio, introduces two up and coming student poets. Guerrero shares their work<br />

with our readers because of “their persevering commitment to their education, to their<br />

art, and to their brave and difficult emotional / physical / spiritual work.” We are<br />

happy to showcase Guerrero and her students in this issue for our readers.<br />

Switching gears, in the essay “Always Been ‘Inside,’” J. Paul Padilla offers<br />

readers a form of alternative rhetoric by stringing together vignettes as a way to<br />

meditate on rhetorical recovery and transformation. These vignettes offer readers an<br />

opportunity to see how writers, like Padilla, can engage in critical analysis through<br />

personal meditation. His work explores the dynamics of doxa and kairos and delinks<br />

readers from the genre of traditional scholarly writing. His meditations relate to<br />

cultural definitions of, and self-definitions for, Latinx communities.<br />

In our final article, “Rhetorical Herencia: Writing toward a Theory of Rhetorical<br />

Recovery and Transformation,” Cristina D. Ramírez explores how Latinx scholars can<br />

develop rhetorical concepts and/or approaches in and out of the classroom to account<br />

for rhetors who are excluded from traditional rhetoric. Ramírez does this by<br />

introducing and defining the concept of rhetorical herencia (heritage) while focusing on<br />

her grandmother’s recovery work.<br />

We conclude our issue with two book reviews. Juan C. Guerra examines the<br />

scholarly collection Bordered Writers: Latinx Identities and Literacy Practices at Hispanic-<br />

Serving Institutions edited by Isabel Baca, Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa, and Susan Wolf-<br />

Murphy. Marlene Galván assesses Steven Alvarez’s Brokeing Tareas: Mexican Immigrant<br />

Families Translanguaging Homework Literacies.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 8

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

We are breaking ground with <strong>LWRS</strong>, the first journal in the field with an all<br />

Latinx editorial board and with a focus on solely Latinx writing and rhetoric. We are<br />

grateful for the opportunity to guest edit this inaugural issue. This issue and all<br />

subsequent issues can be found online at https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com,<br />

a website initiated by Christian Rivera. It is with hope that we look onto the future. It<br />

is with courage and determination that we continue our work. Our lucha is far from<br />

over. Let <strong>LWRS</strong> be a space of expression, opportunity, and dialogue.<br />

Con respeto a todos y gratitud,<br />

Isabel y Isaac<br />

Endnotes<br />

1. Land acknowledgement – Shepherd, J. P. (2019, March). "Indigenous El PASO":<br />

How the Humanities help us SEE El Paso as a native place. Retrieved March 21,<br />

<strong>2020</strong>, from https://humanitiescollaborative.utep.edu/project-blog/indigenousel-paso-how-the-humanities-help-us-see-el-paso-as-a-native-place<br />

2. Land acknowledgement – Lipscomb, C. A. (2016, May). “Karankawa Indians.”<br />

Retrieved <strong>June</strong> 9, <strong>2020</strong>, from<br />

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/bmk05<br />

3. The first newsletter (and a few others) can be found under the archive section on<br />

the <strong>LWRS</strong> website.<br />

4. The call for submission for our inaugural issue can be found in the archive on<br />

the <strong>LWRS</strong> website.<br />

5. The invitation for review can be found in the archive on the <strong>LWRS</strong> website.<br />

References<br />

Latinx caucus. (n.d.). Retrieved <strong>June</strong> 7, <strong>2020</strong>, from<br />

https://ncte.org/groups/caucuses/latinx-caucus/<br />

Villanueva, V., Jr. (1994). Abrazos. Capirotada: NCTE’s Latino Caucus Newsletter, 1,<br />

1.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies ISSN 2687-7198<br />

https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly journal published and supported by the<br />

NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Articles are published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-<br />

Noncommercial-NoDerivs) ISSN 2687-7198. Copyright © <strong>2020</strong> <strong>LWRS</strong> Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and<br />

contributors. Some material is used with permission.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 9

Photographs – 2019 El Paso, Texas mass shooting memorial at Walmart<br />

Photo by Antonio Villaseñor-Baca<br />

A flag made up of both the Mexican and the US flags<br />

displayed at the memorial at the Walmart in El Paso, Texas.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 10

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

Vol. 1, No. 1, <strong>June</strong> <strong>2020</strong>, 11–16<br />

The Fourth Movement: Founder’s Letter for Latinx Writing and<br />

Rhetoric Studies<br />

Iris D. Ruiz<br />

University of California Merced, on land of the Yokuts and Miwuk native<br />

people. 1<br />

Writing this introductory letter as a founding member of this journal gives me<br />

wondrous and chontzin feelings of gratification. This first issue of Latinx Writing and<br />

Rhetoric Studies (<strong>LWRS</strong>) has special significance in that the inaugural issue is guest edited<br />

by Drs. Isabel Baca and Yndalecio Isaac Hinojosa, fellow NCTE/CCCC Latinx<br />

Caucus members.<br />

From the perspective of a former member of twenty years and a co-chair of<br />

the NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus (2015-18), I must say that getting to this point has<br />

proven to have been a journey of camaraderie, self-reflection, activism, and<br />

transformation. Often, Caucus members would discuss in listserv discussions and at<br />

CCCC meetings the politics of citation. We noticed that while we were playing fairly;<br />

we were also playing on an unequal playing field, and through past leaders, like Felipe<br />

de Ortega y Gasca, we understood that these citation politics had a history that was at<br />

least fifty years old. I won’t go into too much detail about this history, but I will say<br />

that the publication of the first issue of <strong>LWRS</strong> is timely in that it accompanies a<br />

recently published historical book about and by the Caucus: Viva Nuestra Caucus:<br />

Rewriting the Forgotten Pages of our Caucus (2019), now available through Parlor Press with<br />

the help of Dr. Stephen Parks, a longtime advocate for the Latinx Caucus. This<br />

historical record documents how we engaged deeply to recover these matters, and in<br />

doing so, we pursued the documentation of our archival presence in the field since at<br />

least 1968. I encourage our readers to check out that history. This issue also includes<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies ISSN 2687-7198<br />

https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly journal published and supported by the<br />

NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Articles are published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-<br />

Noncommercial-NoDerivs) ISSN 2687-7198. Copyright © <strong>2020</strong> <strong>LWRS</strong> Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and<br />

contributors. Some material is used with permission.

Iris D. Ruiz<br />

some very important history in the introduction that was shared with us by Cecelia<br />

Milanes, former co-chair of the CCCC Latinx Caucus and lead editor of “Capirotada.”<br />

Milanes provides our audience a glimpse of what the Caucus has been up to for the<br />

past few decades as we have celebrated each other’s accomplishments even while<br />

we’ve been underrepresented.<br />

Still, today, it is very important for the Caucus to continue to self-represent<br />

and advocate for publication venues within the field of Rhet/Comp. Notable about<br />

this journal is that it is the first one in the field to possess an all Latinx editorial board<br />

and to concentrate solely on Latinx issues related to literacy, writing studies, rhetoric,<br />

and pedagogy through various means of aesthetic and creative expression. We are in<br />

the midst of a political climate, for example, that has painted a very negative picture<br />

of Latinx identities within the United States while the Latinx population is growing as<br />

the largest minoritized ethnic group in the United States. This journal is meant to be<br />

seen as providing a counter-vision to these negative cultural images in service to<br />

creating a better-informed “cultural imaginary.” It is meant to serve as a space where<br />

we, as engaged and informed citizens, can speak back with scholarly inquiry and<br />

creative expression to the current political backlash against Latinxs and to matters that<br />

are important to Latinxs.<br />

There are many examples that the editorial group and contributors could cite<br />

to demonstrate this necessity to highlight and showcase our work and the progress<br />

that is yet to come with the help of an accomplished Latinx scholars editorial board.<br />

Since 2008, the battle for Mexican American Studies and HB 2281, has shown<br />

conservative school board officials possess an unfounded fear toward consciousness<br />

raising curricula and pedagogy. Barrio Pedagogy, for example, laid the critical<br />

foundation for Mexican American Studies in Tucson, Arizona but was rejected by John<br />

Huppenthal and Tom Horne. Our history with struggle for cultural knowledge goes<br />

back much further than 2008, however. For example, Latinx civil rights student<br />

organizations, such as MEChA and even our Caucus, have been partially predicated<br />

upon a reclamation of MesoAmerican culture and history. Like other activist groups,<br />

such as The Black Panther Party seeking to claim a nationalist identity, MEChA<br />

demanded a recognition of the southwestern United States as their ancestral<br />

homeland, “Aztlán,” 2 since 1969, and an end to the inferior and demeaning<br />

perceptions commonly held about them by xenophobic, racist white people.<br />

Today, many “identity” based political groups, such as MEChA and our Latinx<br />

Caucus, are thought of by some as being unnecessary “safe spaces” that claim<br />

“victimhood” status and who do not want to play a part in American meritocratic<br />

culture and/or the “pull-yourself up by your own bootstraps” mentality. Stephen<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 12

The Fourth Movement<br />

Miller, current Senior Advisor for Policy for the Trump Administration, for example,<br />

advises the president on important matters related to immigration policy, the Dream<br />

Act, DACA, and Latinx, Aztlan-seeking and dwelling populations. There is<br />

documentation that illustrates his disdain for student activist groups, such as MEChA,<br />

UNIDOS, the Black Student Unions, and other identity-based groups, and for those<br />

who identified as Mexican, Mexican-American, and/or Chicana/o/x (Gumble, 2018).<br />

However, what people like Miller need to accept and become open to is that Latinx<br />

gente have a culture that departs from settler-colonial cultural understandings, and<br />

white people also have a culture that needs to be reclaimed (Dutch, Irish, Welsh,<br />

Danish, and English, among many others). The historical and cultural dismissal is still<br />

evident today in that settler-colonial schools have failed to account for MesoAmerican<br />

cultural accomplishments, memories, epistemologies, ways of knowing, writing,<br />

reading, healing, and other cultural attributes in a much-needed Ethnic Studies<br />

curriculum. Without highlighting or at least teaching these attributes, forms, or<br />

experiences, there continues to be a clear disregard for those who have suffered from<br />

colonial trauma and a resistance to allowing colonized populations to re-discover their<br />

history, humanity, and existence within the North American, South American, and<br />

Central American imaginary, or as José Martí would call it, “Nuestra América.” It<br />

seems to be faulty reasoning to assume that Latinx’ attempts at cultural reclamation<br />

and sustainability is in inherent dialogue with and opposition to the “American”<br />

culture and that it is anti-American propaganda.<br />

Building from the Naui Ollin (four movement) Mexica philosophy as a<br />

foundation for Barrio Pedagogy, I’d like to briefly consider how one learns resilience<br />

while experiencing political angst through activism and community. When I began my<br />

service as co-chair, I immediately began the process of deep self-reflection about my<br />

role, about the Caucus membership, about the civil rights struggle, about OUR place<br />

within the academy, and about my being a colonized Latina, now representative of<br />

many other gente with colonial pasts. I began to reflect on what all of this meant to<br />

me and about how intimidation and crass behavior would be obstacles to overcome.<br />

The precious knowledge I gained from these self-reflections manifested into a vision<br />

for the Caucus: greater representation, greater visibility, and a visibly greater group<br />

identity both offline and online. We set out to increase our precious knowledge as a<br />

collective, so on a path toward further knowledge attainment, we began to study what<br />

had happened in the past, where we were headed, and how NCTE and CCCC<br />

represented us and valued us. With that goal in mind, the Caucus went to Oregon in<br />

2017 and held another spectacular workshop, “Latinxs Taking Action In and Out of<br />

the Academy,” with local activists, poets, writers, peers, and artists, musicians who<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 13

Iris D. Ruiz<br />

performed culturally conscious rhetorics. We wanted to celebrate and showcase the<br />

Latinx voice and presence in Portland, Oregon.<br />

The lesson gained in Portland was something I documented and wrote about<br />

in Latino Rebels (2017). In a nutshell, there were clear examples, which I videotaped, of<br />

a continued distance between the Latinx Caucus workshop and the broader CCCC<br />

conference proceedings. “Latinxs Taking Action In and Out of the Academy”<br />

showcased local activists, poets, writers, peers, and even musicians performing<br />

culturally conscious rhetorics to showcase the Latinx voice and presence in Portland,<br />

Oregon. I think as a more seasoned Caucus leader, I was compelled to start<br />

decolonizing this divide--the way I saw how it affected members, myself, and those<br />

not present. In short, I tried to call attention to this divide in a conference review that<br />

I wrote and published “rogue” through Latino Rebels.<br />

I began to seriously work with decolonial theory and practice in 2015, roughly<br />

the same year that I was voted in as the Latinx Caucus co-chair along with Raúl<br />

Sánchez. I became interested in this work when I wanted to problematize what it<br />

meant to occupy the problematic trope of the “student of color.” Doing so was the<br />

early stage for creating our edited collection Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition: New<br />

Latinx Keywords for Theory and Pedagogy (2016), a collection of “decolonized keywords”<br />

to mentor emerging scholars and provide a venue to publish and expose more of our<br />

Latinx “gente.” We were invited to present at the Conference on Community Writing<br />

in the fall of 2017, where Steven Alvarez, Candace de Leon-Zepeda, and Jose Cortez<br />

spoke about the empowering process of being able to write for this collection from a<br />

decolonial lens. In addition, we saw the Caucus continue to grow. We gained and were<br />

sharing precious knowledge, the second movement.<br />

In 1968, the Caucus was only a handful of people struggling with many of the<br />

same issues we experience today. Now, we have over 100 members, and we are<br />

experiencing a Latinx literary and scholarly renaissance that I will refer to as the third<br />

movement of the Nahui Ollin: Huitzilopochtli. Within the past decade, it is apparent<br />

that we’ve discovered our “will to act” in addition to our previous moments of deep<br />

self-reflection (Tezcatlipoca), gaining precious knowledge (Quetzalcoatl). I predict that<br />

as with the fourth movement of the Nahui Ollin, our Caucus is now moving into the<br />

fourth state of transformation (Xipe Totec) (Arce, 2016).<br />

More recently our activism has been visible through our work on anti-racism<br />

and against white supremacy. In 2018, we voted to boycott CCCC 2018 in Kansas<br />

City, Missouri. We initiated what became the Joint Caucus Statement on the NAACP<br />

Travel Advisory, and we contributed to the Joint Caucus Response as well. Without<br />

going into too much detail with these documents, because they speak for themselves,<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 14

The Fourth Movement<br />

we witnessed our initial will to act and to speak about the CCCC organization’s<br />

responses to our concerns with the creation of the Social Justice Action Committee<br />

(SJAC) and the SJAC all-conference event that we feel emulates our regular<br />

Wednesday workshops where we invite local activists, writers, poets, musicians, and<br />

scholars. We also recently added our joint bibliography to CompPile. <strong>LWRS</strong> is the<br />

continuance of our transformative potential, our Xipe Totec, through which we will<br />

continue to seek transformative change through collective action, self-representation,<br />

and actualization, and we welcome everyone aboard!<br />

Endnotes<br />

1. Land acknowledgement – Diversity statement: University of California, Merced.<br />

(<strong>2020</strong>). Retrieved February 26, <strong>2020</strong>, from<br />

https://diversity.ucmerced.edu/accountability/policies-principles/diversitystatement<br />

2. “Aztlán,” is the mythical homeland of all MesoAmerican people who reside on<br />

both sides of the United States and Mexican border but were colonized by the<br />

Spanish in the 1500’s and by the English and other European settlers in 1848.<br />

These people claim indigenous roots to this geographical territory that was once<br />

the location of the fierce and intelligent Mexica, Aztec, Mayan, Mixtec, Toltec<br />

and other tribes who intermixed and were said to live harmoniously in the region<br />

before colonization. While “Aztlán” is largely regarded as a mythical homeland,<br />

its location is debated and is thought to be most of the southwestern United<br />

States.<br />

References<br />

Arce, S. M. (2016). Xicana/o indigenous epistemologies: Toward a decolonizing and<br />

liberatory education for Xicana/o youth. In D. M. Sandoval, A. J. Ratcliff,<br />

T. L. Buenavista, & J. R. Marín (Eds.), White Washing American Education: The<br />

NewCulture Wars in Ethnic Studies (pp. 11–42). Praeger ABCCLIO.<br />

García, R., Ruiz, I. D., & Hernández, A. (Eds.). (2019). Viva nuestro caucus: Rewriting<br />

the forgotten pages of our caucus. Parlor Press.<br />

Gumbel, R. (2017, February 22). Stephen Miller was no hero fighting left-wing<br />

oppression at Santa Monica High School. LA Times.<br />

Ruiz D. (2017, March 29). A Decolonial CONFERENCE Review: Meditations on<br />

inclusivity and 4 c's '17 in Portland, Oregon. Retrieved February 29, <strong>2020</strong>,<br />

from https://www.latinorebels.com/2017/03/29/a-decolonial-conferencereview-meditations-on-inclusivity-and-4-cs-17-in-portland-oregon/<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 15

Iris D. Ruiz<br />

Ruiz, I. D., & Sánchez, R. (2016). Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies: New<br />

Latinx Keywords for Theory and Pedagogy. Palgrave Macmillan.<br />

About the Author<br />

Iris D. Ruiz earned her Ph.D. from the University of California San Diego and is a<br />

Lecturer at the University of California Merced. Noteworthy publications in rhetoric<br />

and composition include Reclaiming Composition for Chicanos/as and Other Ethnic Minorities:<br />

A Critical History and Pedagogy (2016), Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition: New Latinx<br />

Keywords for Theory and Practice (2016), and Viva Nuestro Caucus: Rewriting the Forgotten Pages<br />

of our Caucus (<strong>2020</strong>).<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies ISSN 2687-7198<br />

https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly journal published and supported by the<br />

NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Articles are published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-<br />

Noncommercial-NoDerivs) ISSN 2687-7198. Copyright © <strong>2020</strong> <strong>LWRS</strong> Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and<br />

contributors. Some material is used with permission.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 16

Photographs – 2019 El Paso, Texas mass shooting memorial at Walmart<br />

Photo by Gaby Velasquez<br />

Mourners at the memorial.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 17

Photographs – 2019 El Paso, Texas mass shooting memorial at Walmart<br />

Photo by Gaby Velasquez<br />

Memorial for David Johnson<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 18

Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies<br />

Vol. 1, No. 1, <strong>June</strong> <strong>2020</strong>, 19–47<br />

Rhetorics of Translation in Tino Villanueva’s Crónica de mis años<br />

peores (Chronicle of My Worst Years)<br />

Aydé Enríquez-Loya<br />

California State University Chico, on land of the Mechoopda people. 1<br />

In the rhetorics of translation, in the system of discourse we use to translate meaning,<br />

there is a gap between what is written in the original text and what is understood<br />

through the act of translation. 2 A space of disruption is created in the attempt to reinscribe<br />

what a text says and what a translator claims it says. Edgar Andrés Moros<br />

(2009) argues that the binary distinctions between the theoretical and practical<br />

understandings of translations and translation studies are problematic. He states that<br />

the “distinctions are seen as arbitrary and culturally determined” and “generally used<br />

to maintain power differentials,” and he goes on to explain that these oppositions are<br />

unnatural human constructs (Moros, 2009, p. 8). Moros maintains that despite the<br />

belief that the practice of translation is free from theoretical or ideological choices, the<br />

fact remains that “even if translators do not write about these choices as theory, there<br />

is an implicit theory that they have created and followed, and which may be inferred<br />

at a later time” (2009, p. 11). Furthermore, Jose M. Davila-Montes (2017) argues,<br />

“Translations advertise the existence of a text by, paradoxically, causing it to<br />

‘disappear’ in its original form and then by taking over its identity; a translation is the<br />

very illusion of reading” the original text (p. 1). In addition, translators are typically<br />

given the creative freedom to translate while adhering to the overall message of a text,<br />

but before translators can translate, they must interpret the text from and for their<br />

own understanding. And so, their translation is a reinterpretation of a text filtered<br />

through their own ideological, theoretical, rhetorical, and cultural understandings.<br />

Their translation is a re-inscription of a story upon the original text.<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies ISSN 2687-7198<br />

https://latinxwritingandrhetoricstudies.com<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>: Latinx Writing and Rhetoric Studies is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly journal published and supported by the<br />

NCTE/CCCC Latinx Caucus. Articles are published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-<br />

Noncommercial-NoDerivs) ISSN 2687-7198. Copyright © <strong>2020</strong> <strong>LWRS</strong> Editors and/or the site’s authors, developers, and<br />

contributors. Some material is used with permission.

Aydé Enríquez-Loya<br />

Tino Villanueva is a prolific Chicano poet, relying on memory to serve as his<br />

muse to write about oppressive educational systems, the erasure and denial of Mexican<br />

American history, learning to defend himself in a foreign language, and interrogating<br />

and coming to terms with Indigenous heritage. In Crónica de mis años peores (Chronicle of<br />

My Worst Years), Villanueva tells the story of his childhood growing up in Texas as a<br />

disillusioned self-recognition of himself as an encumbering remnant of conquest and<br />

domination to America. 3 In the process of telling this story, however, Villanueva loudly<br />

denounces the continued perpetuation of a colonial history deeply embedded within<br />

every fiber of the American education system. Still, while this story is a story that he<br />

tells, this story is not the story that is translated. Villanueva utilizes Spanish almost<br />

exclusively within his Crónica de mis años peores publication. In doing so, he displaces<br />

readers whose first language is not Spanish and who must resort to English translations<br />

of his work. The English translation provided by James Hoggard creates a slightly<br />

different story that adheres to the binary Moros refers to in that Hoggard asserts the<br />

colonial gaze, seeks to control the text, and is dismissive of the decolonial strategies<br />

exhibited in the work. Villanueva’s rhetorical choices of Spanish for this collection is<br />

reminiscent of Gloria Anzaldúa’s resistance to write only in English or to avoid too<br />

much Spanish. Anzaldúa (2007) proclaims that “[her] tongue will be illegitimate” if she<br />

had to accommodate English speakers by not speaking in Spanglish, and that she’s<br />

constantly forced to choose between English or Spanish and or to translate to English<br />

(p. 81). Like Anzaldúa, Villanueva’s use of Spanish throughout the text almost<br />

exclusively marks his text as an act of defiance, and when he refuses to translate himself<br />

by bringing someone else to do it, this substitution is, in and of itself, an act of<br />

resistance.<br />

Before I go any further, let me pause and first position myself in order to<br />

contextualize the source of my resistance based on my embodied experience. My<br />

positionality is based on the experiential recognition that translations are complicated<br />

by cultural histories, time, and geographic location. Furthermore, as someone who<br />

grew up on the border, I learned early on to read in-between the lines across bordered<br />

spaces as a matter of survival, both literal and metaphorical. I was born in El Paso,<br />

Texas, and I spent most of my childhood in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua Mexico. I did<br />

not learn to speak English until I was 8 years old, and the dual languages are still a<br />

source of tension, especially when my students question whether they should take an<br />

English class from me, given my Spanish last name. Growing up translating for my<br />

mother taught me that the practice of translation is complicated. Some things cannot<br />

be translated. Words are not always enough. As a child, I found myself utilizing<br />

memories, senses, and even dreams to try to capture the words I needed to convey<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 20

Rhetorics of Translation in Tino Villanueva’s Cronica de mis años peores<br />

meaning to my mom saying things such as, “Es como decía mi Abuelita, o huele como<br />

cuando la tierra se hizo mala.” I’m not sure how successful I was in trying to convey<br />

the right meaning to my mother, but I do know that this lived experience led me to<br />

constantly question how Spanish and English is translated. 4 As a rhetorician now, it’s<br />

led me to interrogate the intentionality and source of mis/translations and implications<br />

of mis/translations on the original text and on their various audiences. Thus, I insist<br />

that there is a gap or space created between translations that calls for scrutiny and<br />

interrogation. This practice can inform and transform both texts in its ability to<br />

unmask the process of translation, show the subtle shifts in meaning and their<br />

implications, and ultimately hold translators accountable.<br />

The interrogation of a translation is more complicated than simply finding the<br />

equivalent or near equivalent word in a different language. I base this understanding<br />

both from my lived experiences and from the established work in cultural rhetorics<br />

and translation studies. Cultural rhetoric scholar, Angela Haas (2008) explains that<br />

language is culture specific; memory and stories are culturally and locally based (p. 9-<br />

10). Similarly, in translation studies, Laura Gonzales (2018) writes that “language is a<br />

culturally situated, embodied, lived performance” and thus calls for “[c]ountering<br />

traditional notions of translation that limit the analysis of language transformation to<br />

written alphabetic texts alone” (p. 3). Thus, as a cultural rhetorician my approach to<br />

reading these poems by Villanueva involves trying to understand the subtle shifts in<br />

the language used to make meaning and to always remember that language and culture<br />

are inextricably linked. My reading of Crónicas de mis años peores is heavily influenced not<br />

only by his history but also by Chicano and migrant worker history in Texas and by<br />

my own history growing up on the border. My readings of these poems are my way of<br />

recovering a story that has been suppressed by the translation, specifically by<br />

Hoggard’s translation.<br />

My scholarship has always been rooted at the crossroad of rhetorics and<br />

poetics, specifically by writers of color, building and or maintaining real and rhetorical<br />

alliances, and creating a discursive community that seeks to aid in our mutual survival.<br />

I was initiated into this path by Native American writers such as Leslie Marmon Silko<br />

(1977), 5 Lee Maracle (2015), and Malea Powell (2012). 6 Powell taught me about the<br />

power of stories and storytellers, but from all of them, I have come to understand that<br />

story is theory. Reading stories as theory makes me cognizant that as I theorize, I am<br />

also in the process of creating another story and aware of the ethics that must underline<br />

my practice. In this article, I will first situate the presence and necessity of third space<br />

as a rhetorical framework to recover Villanueva’s story. Second, I will propose<br />

different rhetorical strategies that can be used as a decolonial praxis within Villanueva’s<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 21

Aydé Enríquez-Loya<br />

text. Lastly, I will put theory into practice by building a story that showcases how the<br />

rhetorics of translation can be used to tease out a decolonial story and in that expose<br />

the dangers of mis/translations. This final section will present a close rhetorical and<br />

translational analysis of a few selected poems from Crónica de mis años peores.<br />

Third Space Politics of Rhetorics and Poetics<br />

The understanding and denial of a relationship between a translator and a text creates<br />

a situation where the actual text and the translation of it can be two separate and highly<br />

divergent narratives. While they are both attempting to tell the same story, the<br />

translation of a text carries an imposed meaning dependent on the translators’ personal<br />

ideologies and theoretical understandings of the text. For example, as a graduate<br />

student, I first encountered Tino Villanueva’s poem “Haciendo Apenas La<br />

Recolección” in the anthology Literature and the Environment edited by Lorraine<br />

Anderson, Scott P. Slovic, & John P. O’Grady (1999). Immediately, I was struck by<br />

the editors’ loose translation of the title and synopsis provided in the introduction to<br />

the poem. “Haciendo Apenas la Recolección” originally from Villanueva’s poetry<br />

collection Shaking Off the Dark (1984/1998) is translated by the editors as “Barely<br />

Remembering” (Anderson, Slovic, & O’Grady, 1999, p. 219) The editors’ translation<br />

of the title suggests the grasping of threads of memory, a faint remembrance that needs<br />

more work. The use of “barely” also carries connotations of scarcity and insufficiency,<br />

suggesting that there are only scarce or insufficient memories. But that is not the case.<br />

“Haciendo apenas la recolección” can also be translated as “Barely Making<br />

Recollection” or “Just Now Making Recollection.” 7<br />

The key to understanding the real significance of this title and the poem is by<br />

recognizing the theoretical and cultural discourses Villanueva’s narrative has created.<br />

Alfonso Rodriguez (1998) suggests, “As a former migrant worker, [Villanueva] has<br />

personally experienced the struggle, and he has developed a way to deal with his<br />

attitudes and frustrations through the creative process in the form of poetry of social<br />

commitment” (p. 84). Furthermore, in “Haciendo apenas la recolección,” Villanueva<br />

retraces the routes of his childhood and reality as a migrant worker in Central Texas.<br />

The journey he undertakes in the poem is the recovery of his story—one that provides<br />

a “sense of peace and liberation” through the process of retelling his story (Rodriguez,<br />

1998, p. 85). As such, in either of my suggested translations, the speaker is not grasping<br />

at faint memories but is instead just now initiating the process of recalling these<br />

events. Additionally, there is a significant difference between Recolección and<br />

Recordar, which is the literal translation of “to remember.” Recolección, to recollect,<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 22

Rhetorics of Translation in Tino Villanueva’s Cronica de mis años peores<br />

has a more physical and active presence. The act of physically bringing things together<br />

and, even more pointedly, bringing things together that have been together and somehow<br />

belong together.<br />

So, despite the editor’s translation of the title and by association the poem<br />

itself, Villanueva’s memory is not failing. He is just getting started. The distinct<br />

difference between the text and the imposed reading creates a rhetorical space, an<br />

intermediate space, that exists between the original text and the imposed text. One in<br />

which we must ask, how much of the language we use cannot be translated with words<br />

alone but requires an embodied and lived understanding of the text beyond language?<br />

And what happens in the space created between the text and its mistranslation? Whose<br />

story are we really hearing in a translation? And, how can we tell the difference?<br />

Within the space, the space created between the original and translation of a<br />

text, the audience can interrogate the imposition of a translation, the colonial gaze of<br />

a text, and denounce it. Allow the text to speak for itself. But doing so calls for an<br />

alternative discourse and rhetorical framework. As Haas (2008) & Gonzales (2018)<br />

explain, in order to begin the interrogation process, we must consider Villanueva’s<br />

cultural underpinnings and position the text in the borderlands. In Borderlands/La<br />

Frontera: The New Mestiza, Gloria Anzaldúa (1987/2007) describes the borderlands as<br />

rupturing spaces where time, history, and peoples collide. To live in the borderlands is<br />

carrying the weight of history on your back, to carry the “hispana, india, negra, española,[y]<br />

gabacha” on your back (Anzaldúa, 1987/2007, p. 216). To live in the borderlands is to<br />

recognize that in this space<br />

you are the battleground<br />

where enemies are kin to each other;<br />

you are at home, a stranger,<br />

the border disputes have been settled<br />

the volley of shots have shattered the truce<br />

you are wounded, lost in action<br />

dead, fighting back; (Anzaldúa, 1987/2007, p. 216)<br />

It is within this context that the rhetoric of the borderlands emerges. It is rhetorically<br />

informed by history, bodies, tongues, scars, and open wounds. It is rhetoric<br />

challenging presence over absence, erasure, and denial. As the child of migrant<br />

workers, Villanueva expresses these precise feelings of being stranger at home and<br />

carrying the weight of his people’s history on his back. In addition, Adela Licona<br />

(2005) terms this as a “(b)orderlands’ rhetorics,” which she argues “move beyond<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 23

Aydé Enríquez-Loya<br />

binary borders to a named third space of ambiguity and even contradiction” (p. 105).<br />

Strategically, Licona places parentheses around the “b” in borderlands in order “to<br />

materialize a discursive border” and to “interrupt any fixed reading of the notion of<br />

(b)orderlands” (p. 105). The materialization of this discursive space is necessary for<br />

stories like Villanueva, both to materialize and counter the narratives that have been<br />

written about marginalized communities, in this case migrant workers. Villanueva’s<br />

story is a borderland story where the weight of history and the oppressive education<br />

system seek to consume him. In a state of ambiguity, he is led to feel like a walking<br />

contradiction. Ni de aquí, ni de allá. But as he negotiates history and the imposition of<br />

history upon his body and memory, Villanueva shows that borderland stories challenge<br />

us to consider how these spaces are and should be about decolonial work. However,<br />

Hoggard’s imposed translation undermines its capacity, ignores the decolonial work,<br />

and perpetuates a colonial imposition and erasure upon brown bodies.<br />

Through Hoggard’s translation, Villanueva’s story is trapped and bound by<br />

colonial practices. Emma Pérez (1999) in The Decolonial Imaginary discusses this third<br />

space as the “practice that implements the decolonial imaginary” (p. 33). It is within<br />

this space of the decolonial imaginary that we as scholars can interrogate and renounce<br />

the colonial presence within academia. Furthermore, Pérez argues that a decolonial<br />

imaginary utilizes third space feminisms to contradict and challenge dominant<br />

discourse (1999, p. xvi). She says, “the decolonial imaginary in Chicana/o history is a<br />

theoretical tool for uncovering the hidden voices of Chicanas that have been relegated<br />

to silences, to passivity, to that third space where agency is enacted through third space<br />

feminism” (Pérez, 1999, p. xvi). The decolonial imaginary is a tactic by which to<br />

challenge the colonial history embedded within the lands, bodies, and stories.<br />

Additionally, Chela Sandoval (2000) shows that third-space feminism is “a theory and<br />

method of oppositional consciousness” and that such theory is “not inexorably<br />

gender-, nation-, race-, sex-, or class-linked” (p. 197). Utilizing third space<br />

methodology, we can build theory to illustrate the intricate process of decolonizing the<br />

translation of a text. By purposefully reading Villanueva’s work through these<br />

methodologies, we are enabled then to recognize the different colonial histories that<br />

are embedded within this bordered space, trapped by coded languages and colonizing<br />

legacies. Our task is to actively resist this colonial history by reclaiming and recovering<br />

Villanueva’s history. Enacting this process of reclamation and recovery is mediated by<br />

positioning ourselves in direct opposition in theory and in practice to the colonial<br />

history of the border. We must carve out a space to make this work happen. Other<br />

scholars, such as Licona (2005), have also articulated the intricacies and complexities<br />

of third space sites that can also shift from not only a practice, as Perez (1999) argues,<br />

<strong>LWRS</strong>, <strong>2020</strong>, 1(1) | 24

Rhetorics of Translation in Tino Villanueva’s Cronica de mis años peores<br />

but also a location (p. 105). Licona writes, “As a location, third space has the potential<br />

to be a space for shared understanding and meaning-making. Through third-space<br />

consciousness then dualities are transcended to reveal fertile and rhetorical<br />

performances into play (2005, p.105). Third spaces as practices and locations for the<br />

decolonial work provide the methodology for oppositional thinking that, in the<br />

Villanueva’s case, can be enacted in both capacities. Within Villanueva’s collection,<br />

readers have multiple narratives that overlap and counter each other: his original text<br />

and Hoggard’s translation. Teasing out the embedded story, as I have performed in<br />

my own translation, provides an alternate narrative, and this third space allows us to<br />

transcend beyond the text and engage the decolonial process as a performative action.<br />

Additionally, Villanueva’s role within the Chicano movement speaks to his<br />

positioning within the context of this third space. Heralded as a Chicano poet,<br />

Villanueva’s work, shaped by Chicano activism and the Vietnam war, was foundational<br />

to the Chicano Renaissance (Lee, 2010, p.174). Within Chicanismo, scholars have<br />

problematized the invocation of indigenous identity or a mestizaje as central to identity<br />

formation or legitimacy. 8 This is important to note since Villanueva self-identifies as a<br />

Chicano and asserts his position within the Chicano movement. And within his<br />

collection, Villanueva includes poems that interrogate and reclaim his Indigenous<br />

heritage, such as “Cuento del cronista,” where he invokes Tlacuilo, an Aztec scribe,<br />

and chastises Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca as a “maldito explorador” (“Cuento del<br />

cronista,” 1987/1994, p. 42). In this poem, he asks Tlacuilo for a blessing, to keep him<br />

honorable, to keep him from forgetting his lineage, and in the end, Villanueva comes<br />

to terms with the violence of his heritage and history. Iris Deana Ruiz (2018), for<br />

example, explains this instance as the invocation of “La indigena” trope which, she<br />

says, “seeks to revisit and revitalize the knowledges … and cultural practices of Pre<br />

Columbian indigenous peoples in MesoAmerica [who]…left behind priceless, even<br />