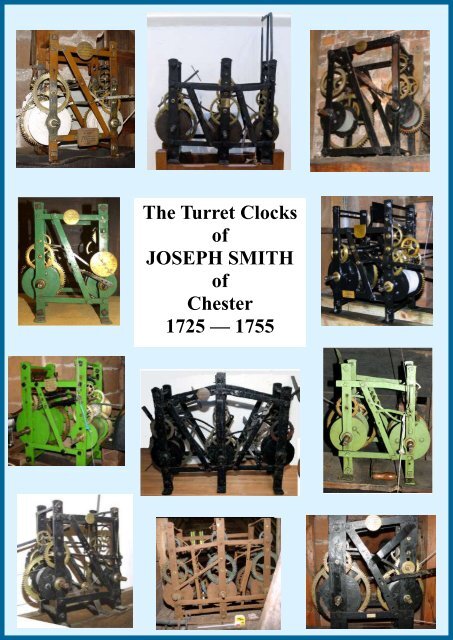

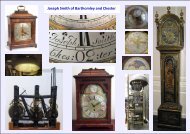

Joseph Smiths Turret Clocks

Some images and history on the surviving turret clocks by Joseph Smith

Some images and history on the surviving turret clocks by Joseph Smith

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The <strong>Turret</strong> <strong>Clocks</strong><br />

of<br />

JOSEPH SMITH<br />

of<br />

Chester<br />

1725 — 1755

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith’s turret clocks<br />

Location Date Still working in<br />

original location?<br />

Chester Cathedral 1725 Now in a private<br />

collection<br />

St Michael’s Church, Shotwick 1726 Yes<br />

Features of interest<br />

Three train ting tang clock<br />

1¼ second pendulum<br />

St Peter’s Church, Little Budworth 1727 Yes Much of the original documentation<br />

survives.<br />

Fine small clock in good condition<br />

St Lawrence’s Church, Stoak 1732 Not working when we<br />

Single hander<br />

visited but appears to<br />

be complete<br />

St John’s Church, Chester 1746 Replaced Three train movement<br />

Now in a private collection<br />

The ‘Rescued clock’ - Not working.<br />

Three train ting tang clock<br />

In a private collection<br />

St Mary’s Church, Tilston 1750 Yes Fine small clock in good condition.<br />

St Nicholas’ Church, Burton 1751 Yes Single hander<br />

St Mary’s Church, Mucklestone - Yes Much altered<br />

St Alban’s Church, Tattenhall - Yes Maybe <strong>Joseph</strong>/Gabriel(1) Smith<br />

Poulton Hall 1755 Moved a short<br />

distance<br />

Still owned by the same family.<br />

Single hander<br />

Adlington Hall 1755 Replaced but safely<br />

All clock parts retained<br />

stored<br />

Pengwern Hall - Not working when we<br />

visited but apparently<br />

Requires some restoration<br />

Single hander<br />

complete<br />

Whitmore Hall - Rusted up Still in original location

Chester Cathedral Clock 1725<br />

When <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith arrived in Chester, there was already a clock in the cathedral, which was wound and<br />

maintained by Charles Whitehead, smith and mason of the city. In September 1724, the cathedral accounts book<br />

lists £0 5s 0d spent ‘at Bargaining for a new Church clock’. This may well have been a meeting between <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

Smith and the cathedral authorities, at which the clock was offered as a ‘master piece’. No records of any monies<br />

spent on acquiring the clock have yet been found, which could indicate that it was made as a gift. Towards the<br />

end of the following year James Comberbach, timber merchant, was paid £2 11s 0d ‘for timber for ye clock case’<br />

and two months later Charles Whitehead received his final payment of £0 8s 0d for ‘tending ye old clock’.<br />

Even though religious communities relied on their clocks to timetable their lives and services, clocks were not<br />

highly valued. They are rarely mentioned in church histories, whereas bells are described in detail. The cathedral<br />

archives have been only partially indexed. The four account books contain the only known records relating to <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

Smith’s clock that were written during his lifetime. All the available indexes have been searched for other<br />

references to the clock. It was customary for a clockmaker to commit to maintain a turret clock during his lifetime.<br />

This was certainly the case with the cathedral clock. <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith was paid annually, usually at Michaelmas,<br />

for maintenance of the clock. The annual salary for the job was £0 16s 0d and remained unchanged from 1727<br />

until 1766.

Chester Cathedral Clock 1725 p2<br />

The payment was increased occasionally if repairs were required, for example one of the bells was sent to<br />

London for re-casting during the 1730s; on 18 th December 1738-9, after the bell’s return this entry was put<br />

in the accounts book: ‘To Mr Smith for cleaning and regulating the clock after the Great Bell was put up -<br />

£0 9s 0d.’<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith’s connection with the cathedral was made even closer when he sent his boys to the King’s<br />

School. The school was founded by King Henry VIII in 1541 following the dissolution of St Werburgh's<br />

Abbey, which became Chester Cathedral. It was housed in the former monastic refectory for most of the<br />

next 400 years. It was to have twenty-four poor and friendless boys aged between nine and fifteen. The<br />

boys, usually termed King's Scholars, were elected by competitive examination and received a free<br />

education and an allowance. The ‘poor and friendless’ requirement must have been less stringently<br />

enforced as the years passed. <strong>Joseph</strong>’s eldest son, John was first listed as a King’s Scholar in the account<br />

book in 1733, followed by Gabriel(2) in 1735, Thomas in 1737 and Samuel in 1742. It is not known how<br />

long the boys attended the school, but Samuel was still there in 1745.<br />

In October 1744 Thomas was paid the year’s salary for taking care of the clock and the following year, Mrs<br />

Smith collected her husband’s salary. Payments to <strong>Joseph</strong> then continued until 1763, when Gabriel(2) was<br />

paid ‘his year’s salary’. After that time, <strong>Joseph</strong> was paid for three more years, the final payment to him<br />

being on 4 th April 1766. John Smith continued the maintenance of the clock until his last salary was paid on<br />

9 th November 1781.<br />

The Smith clock continued in service until 1872/3 when it was replaced by a flatbed Westminster chiming<br />

clock made by JB Joyce & Co. of Whitchurch. Like its predecessor, the Joyce clock had no dial, but simply<br />

told the time by full quarter chiming and striking the hours. At the time of the clock’s installation, the 1867<br />

carillon was re-sited. It lessened the job of the bellringers, by playing the first lead of Bob Triples. The<br />

Joyce clock and carillon were themselves superseded by an electric chiming mechanism which was<br />

installed in the new Addleshaw Bell Tower when it was completed in 1975.

Chester Cathedral Clock 1725 p3<br />

The Smith clock was auctioned by Christies in their sale of ’Important <strong>Clocks</strong>’ on 7th December 2005.<br />

The catalogue stated:<br />

A GEORGE 1 IRON AND BRASS THREE TRAIN POSTED FRAME TURRET CLOCK<br />

DATED 1725.<br />

JOSEPH SMITH<br />

With in-line trains having rectangular section posts with splayed feet and bolted frame, oak<br />

barrels, turned iron collets, the going train with recoil anchor escapement, the quarter strike<br />

train in the centre with brass countwheel and internal brass fly, square brass signature plaque<br />

applied to the centre post engraved <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith Chester 1725, the hour strike train on the left<br />

side with iron countwheel and external fly with iron vanes.<br />

THE FRAME: 15½in x 14in x 25in (39.5cm x 36cm x 63.5cm)<br />

Three train turret clocks from this period are particularly rare. The present example has the<br />

added rarity of having the going train on the right side as opposed to the normal position<br />

between the quarter and hour trains.<br />

This clock has no ‘drive-off’, so has never driven a dial, indicating time by its strike and ting-tang<br />

quarters. Originally its pendulum was wall mounted.<br />

The clock has returned to Chester and is in a private collection.

St Michael’s Church, Shotwick, Cheshire, 1726<br />

In 1726, <strong>Joseph</strong> was approached by the<br />

churchwardens of St Michael’s Church, Shotwick, a<br />

small village north west of Chester. A new clock was<br />

required to replace an old, unreliable one in the<br />

tower.<br />

The sturdy, small, two train movement driving a<br />

single dial on the south side of the tower and striking<br />

the hours on a large bell is now electrically autowound.<br />

In common with the cathedral clock and all<br />

the turret clocks he produced afterwards, this clock<br />

has a detached, wall mounted pendulum.<br />

On the clock frame is a brass plaque bearing the following inscription in cursive script:<br />

Tho Aston minister<br />

Geo Roe John Coxon<br />

Churchwardens 1726<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith<br />

Chester<br />

The Churchwardens’ Accounts for 1726 record,<br />

‘Mr Smith of Glovers Stone for ye Church Clock<br />

£10 10s and for ye large stone weight 5s and allowed<br />

him for ye old Church Clock [Total] £10 0 0’.

St Peter’s Church, Little Budworth, Cheshire, 1727/8<br />

In 1727, <strong>Joseph</strong> received a<br />

commission from St Peter’s Church,<br />

Little Budworth.<br />

‘It is agreed this 18th day of<br />

April 1727 between John<br />

Egerton Esqre, and Mr<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith, Clockmaker of<br />

Gloverstone in Chester. The<br />

said Mr Smith for and in<br />

consideration of Ten<br />

Pounds, shall make a large<br />

substantial church clock to<br />

go a week, for Little<br />

Budworth, and to have<br />

strong brass wheels, and all<br />

other work to be firm and<br />

substantial, and to strike as<br />

loud as any week clock shall<br />

doe.’<br />

The face was to be three feet square<br />

with black characters on a white<br />

background though there had been<br />

an option for a face of two feet<br />

square of gilt and gold. It was also<br />

agreed that the parish would find the<br />

stones for the weights and a<br />

carpenter to set up the clock with<br />

boards for a case. Apparently there<br />

had been an earlier clock as <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

Smith was allowed to have the<br />

materials from it.<br />

The clock was to be ready by<br />

midsummer the following year. In<br />

addition to his payment, <strong>Joseph</strong> was<br />

to have 2s 6d a year to keep the clock<br />

in repair. The present dial is dated<br />

1785; this may have replaced the one<br />

installed when the clock was made, or<br />

it may have been simply re-painted<br />

later in the century.<br />

The clock is on the south face of the<br />

tower.

St Lawrence’s Church, Stoak, Cheshire, 1732<br />

A little north of Chester, is the small hamlet of Stoak.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith made a clock for St Lawrence’s church<br />

in 1732.<br />

The movement is built to the Smith pattern, but its<br />

dial, mounted on the west face of the tower, is single<br />

-handed.<br />

A plaque on the frame records in cursive script:<br />

JOHN WILLIAMSON AND CHARLES HILL<br />

CHURCH WARDENS<br />

AP YE 14 1732<br />

JOSEPH SMITH<br />

FECIT

St John’s Church, Chester, 1746<br />

Detail from: St John’s Church, Chester from the Queen’s Park’,<br />

drawn, engraved and published by J. Romney, 1853.<br />

It is likely that <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith made clocks for many of the village churches around Chester, and for some<br />

of the ancient parish churches in the city. Unfortunately Victorian restorations swept away many of<br />

Cheshire’s first turret clocks. <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith met with the church wardens of St John’s early in 1745 to<br />

discuss the possibility of his making a clock for the church; the church wardens’ accounts record £0 1s<br />

6d spent on Mr Smith at the meeting. A few weeks later, £0 2s 6d was paid to <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith in part<br />

payment for the clock and by the end of the year a further £15 was received in full payment .<br />

Unfortunately no description of the clock has been found. <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith received £1 in May 1746 ‘for ye<br />

Watch’; this was an internal clock for the benefit of the clergy. Records survive of a £20 bond outlining,<br />

in effect, a maintenance contract for the new clock:<br />

Date 29 th May 1746. 1 <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith of Gloverstone, clockmaker, 2 Thomas Gorbin and William Jones,<br />

churchwardens. For performance of agreement viz. that I shall every week wind up the new clock and<br />

the watchpiece to be fixed in the church, and clean the same whenever necessary, for 10s. per annum.<br />

Wit: Tho. Patten, W. Fairclough.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith was then paid annually, usually in April or May, his sum of ten shillings, augmented<br />

occasionally by extra payments, for example in October 1749, when he was paid three shillings for<br />

‘altering the watch’. Payments were for winding and cleaning, as required; there was little maintenance,<br />

just new weight ropes, some wire and a new weight, which cost £0 2s 6d. It is not clear when <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

Smith stopped winding the clock; the last entry to record ‘<strong>Joseph</strong>’ was for the year ended March 1764.<br />

For 1765, 1766 and 1768, the book has simply, ‘Mr Smith’. At the end of 1770, <strong>Joseph</strong>’s son, John Smith,<br />

received the annual salary. He continued to wind and repair the clock until replaced by Robert Cawley(2)<br />

or (3) in 1781.

St John’s Church, Chester, 1746, page 2<br />

St John’s was the ancient cathedral church<br />

which lost its status following the dissolution of<br />

St Werburgh’s Abbey. As early as the fourteenth<br />

century there were worries about the decay of<br />

the red sandstone from which it was<br />

constructed. The church suffered many<br />

disasters. The central tower fell down twice: in<br />

1468 and 1572, to be followed in 1574 by the<br />

collapse of the west tower, which was rebuilt<br />

later the same century. In 1860, in a report on<br />

the whole building's condition, it stated,<br />

"there is little chance of the repair of<br />

the fine tower [ie. the west tower],<br />

which is now in a very shattered and<br />

decayed state..."<br />

The west tower collapsed on Good Friday, 1881<br />

after many warnings. Most of the bells were<br />

rescued and it is possible that the <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith<br />

clock was also removed to a place of safety. The<br />

tower was never rebuilt on the old footprint and<br />

only the old ‘stump’ remains. Chester architect<br />

John Douglas designed the present north east<br />

belfry tower in 1886 and a clock was placed<br />

there by JB Joyce and Co. in time for Queen<br />

Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897.<br />

Above:<br />

The tower on the morning of<br />

the fall, 15 April 1881.<br />

Cheshire Archives ZCR<br />

119/1079/131<br />

Left:<br />

This clock was found ready to<br />

the scrapped in a street in<br />

Chester. It was rescued by its<br />

current owner. It may be the<br />

clock which was once in<br />

St John’s Church.

St Mary’s Church, Tilston, Cheshire, 1750<br />

The small village of Tilston,<br />

some thirteen miles south of<br />

Chester has a clock by<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith in the parish<br />

church of St Mary, operating<br />

a single dial on the north<br />

side of its tower.<br />

Tilston’s first clock, by an<br />

unknown maker, had been<br />

made in 1733 at a cost of<br />

£11. It did not perform well<br />

so a replacement was<br />

agreed in 1750. <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

Smith’s small turret clock<br />

which has given, to date,<br />

270 years of service, cost<br />

only £5 3s 0d including the<br />

lead weight.<br />

A small circular plaque<br />

records:<br />

JOHN BARKER JOHN JONES<br />

CH:WARDENS 1750<br />

JOSEPH SMITH<br />

CHESTER FECIT’.<br />

In 1784, Mr Enoch Auchison<br />

was paid £3 19s 0d for work<br />

on the clock. It cost 3s to<br />

carry the clock to him in<br />

Nantwich. In 1812, Mr<br />

Thomas Joyce of Whitchurch<br />

was paid 15s for cleaning<br />

and repairing the clock. Thos<br />

Caldecott was also paid 11s<br />

for cleaning it that year.

St Nicholas’ Church, Burton, Wirral, 1751<br />

A similar clock to that at Tilston, but driving only one<br />

hand on its single dial, was made for St Nicholas’<br />

Church, Burton, Wirral a year later. The style of the<br />

hand is very similar to that on the Stoak clock made<br />

almost twenty years earlier. Its movement is laid out in<br />

the familiar Smith style. This clock also bears a circular<br />

plaque, this time recording:<br />

‘JOHN COOPER SAM L LITTLER CH;WARDENS 1751<br />

JOSEPH SMITH CHESTER FECIT’.<br />

The engraving of this plaque is very similar to that on<br />

the Tilston clock.

St Mary’s Church, Mucclestone, Staffs.<br />

The clock in St Mary’s<br />

Church, Mucklestone closely<br />

resembles others by <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

Smith. It is much altered,<br />

now having a pinwheel<br />

deadbeat escapement and a<br />

long pendulum. The latter is<br />

offset in the Smith manner,<br />

and passes through the floor<br />

to the storey below. The<br />

clock is now auto-wound.<br />

Written records of the clock<br />

have not been traced.

St Alban’s Church, Tattenhall, Cheshire<br />

No records have been found concerning the<br />

purchase or installation of the clock at St<br />

Alban’s, Tattenhall, and its name plaque has<br />

been lost.<br />

Its size, layout and offset pendulum indicate it<br />

is without doubt a Smith clock. The movement<br />

sits in the sixteenth century tower which was<br />

spared during the 1869 restorations.<br />

Two of the six bells were cast by <strong>Joseph</strong>’s<br />

father, Gabriel Smith(1), the tenor, inscribed<br />

‘Peace and prosperity to our benefactors 1710’<br />

and bell number five, inscribed ‘God save the<br />

Queen, Peace and good neighbourhood 1710’.<br />

The pendulum is much heavier and longer than<br />

those on <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith’s clocks.<br />

It is not implausible that the clock could have<br />

been made by Gabriel Smith(1) at the same<br />

time as the bells were cast.

Poulton Hall, Wirral, 1755<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> Smith also made turret clocks for country<br />

houses in the locality; four have been found. The first,<br />

dated 1755 is at Poulton Hall on the Wirral.<br />

It was installed in an outbuilding at the hall and ran<br />

there until 1914 when it was moved and has since been<br />

replaced in its original cupola by an electrical<br />

movement.<br />

The Smith clock was moved twice more, in 1939 and<br />

1989. Its current location is inside another outbuilding<br />

with its single handed dial in a new cupola. The<br />

movement is typical, of the small <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith clocks<br />

and is in working order. Its circular brass plaque is<br />

engraved in cursive script:<br />

‘Edw d Green Esq 1755 <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith CHESTER Fecit.’

Adlington Hall, Cheshire, 1755<br />

Forty-five miles from Chester, a short<br />

distance from Macclesfield, lies the<br />

Adlington Estate. <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith made a<br />

clock for Adlington Hall in 1755.<br />

This was converted to electric auto<br />

winding during the twentieth century but<br />

has been replaced by a synchronous<br />

electric motor which now drives the<br />

clock.<br />

The Smith movement and all its<br />

component parts have been safely stored<br />

away. It is, like the example at Poulton<br />

Hall, typical of <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith’s clocks.<br />

Its plaque reads:<br />

‘CHARLES LEGH ESQ R<br />

JOSEPH SMITH<br />

CHESTER FECIT 1755’

Pengwern Hall, Flintshire<br />

We have not traced any evidence<br />

regarding the date or maker of this<br />

clock at Pengwern Hall, near<br />

Rhuddlan, Flintshire, north Wales.<br />

The estate buildings and the main<br />

hall, now belong to Mencap which<br />

runs one of its three national<br />

colleges there for young people with<br />

learning difficulties.<br />

The single handed clock was not in<br />

going condition when we saw it.<br />

All the Smith design features are<br />

present; its size, the trains and the<br />

setting of the pendulum all closely<br />

resemble others bearing the Smith<br />

name.

Whitmore Hall, Staffordshire<br />

The final clock is at Whitmore Hall in Staffordshire, but we have no confirmation that<br />

this is a clock by <strong>Joseph</strong> Smith. It is located in an old barn at first floor level; it has<br />

not been working for many years so much of its metalwork has rusted. In the roof of<br />

the building is a fine cupola housing the bell and two dials. This clock is a three train<br />

example, with the going train centrally placed between the strike and chime trains<br />

as on the ‘rescued’ clock. Records of the clock’s purchase and installation have not<br />

yet been traced.