Young Writers Collective

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

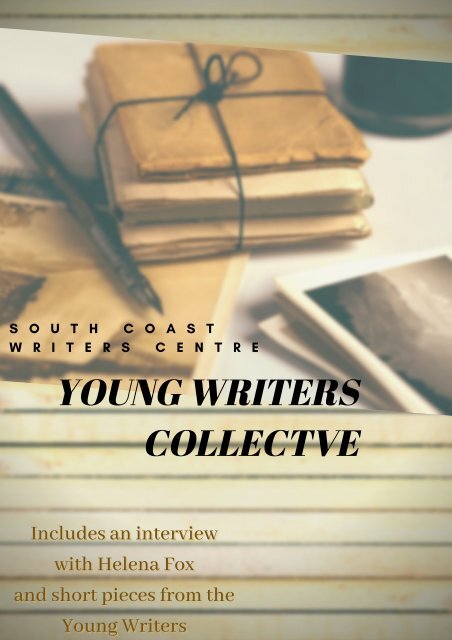

S O U T H C O A S T<br />

W R I T E R S C E N T R E<br />

YOUNG WRITERS<br />

COLLECTVE<br />

Includes an interview<br />

with Helena Fox<br />

and short pieces from the<br />

<strong>Young</strong> <strong>Writers</strong>

An Interview with Helena Fox<br />

about the <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Writers</strong> <strong>Collective</strong><br />

by Leon Vasilakis<br />

Helena Fox is the program facilitator of the SCWC <strong>Young</strong><br />

<strong>Writers</strong> <strong>Collective</strong>, a dynamic group of teenagers who meet<br />

throughout the year to write in a variety of genres. Helena has<br />

had a wonderful career in the arts so far, and is a graduate of<br />

the MFA Program for <strong>Writers</strong> at Warren Wilson College in<br />

North Carolina.<br />

Her debut YA novel How it Feels to Float was released in<br />

Australia and New Zealand in 2019 by Pan Macmillan, and<br />

published in North America by Dial/Penguin Random House. It<br />

is a profound, moving tale of living with mental illness, with a<br />

warm-hearted, funny character named Biz. This makes Helena<br />

perfectly positioned to run an amazing series of workshops for<br />

our young writers—so if you’re interested in joining, please<br />

contact the Centre!

I believe the program has helped many young writers grow<br />

more confident about their writing, learn a great deal about the<br />

writing process, and develop unique writing voices. The<br />

program has also provided young writers with many new<br />

experiences, including regularly sharing their work with others,<br />

providing constructive feedback to their peers, having public<br />

readings, and seeing their work published in the annual zine.<br />

The writers have also had a welcoming and safe space to come<br />

to every week, to share their stories and feel heard.<br />

It is very rewarding to see how supportive the Centre is towards<br />

young writers. Not only does the Centre happily provide a yearround,<br />

workshop-based program that offers young writers a<br />

space to gather, share ideas, and build their community, the<br />

Centre also offers many opportunities for young writers to read<br />

their work publicly and publish their work.

The <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Writers</strong> program began mid-2014, with a threemonth<br />

course that focused on various writing forms. Different<br />

tutors ran monthly sessions and Centre staff ran extra support<br />

sessions. At the end of the course, I offered to run out-of-season<br />

workshops until the 2015 program, which ran again with a<br />

similar format.<br />

In 2016, due to the high interest and enthusiasm of the<br />

young writers, the course became a regular, year-long program<br />

of fortnightly sessions run by me, with some guest tutors. In<br />

2017, again due to the eagerness of the young writers, the<br />

program began running weekly. Today, the <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Writers</strong><br />

<strong>Collective</strong> (aged 14 and up) meets throughout the school year to<br />

explore prose, poetry, scriptwriting and non-fiction writing,<br />

and they appear at numerous public readings. The <strong>Young</strong><br />

<strong>Writers</strong> program is thriving; the numbers in the <strong>Collective</strong> are<br />

consistently full, and there is a waitlist.

Helena Fox is a writer and<br />

creative mentor. Born in Peru,<br />

Helena spent time in Spain,<br />

the UK and Samoa throughout<br />

her childhood, settling in<br />

Australia at age eleven, and<br />

gained a Master of Fine Arts in<br />

the United States. She runs<br />

workshops on creative writing<br />

and is proudest of her work<br />

helping young writers find<br />

and express their voice.<br />

Her workshops and her<br />

writing have a focus on<br />

improving mental health.<br />

Helena's novel How it Feels<br />

to Float won the Victorian<br />

Premiers Literary Award for<br />

Writing for <strong>Young</strong> Adults.

I think the program has worked so well because the focus of the<br />

workshops has been on exploring and having fun with writing,<br />

rather than on ‘teaching’ young people how to write. Through<br />

experimentation, discussion, and responding to challenging and<br />

fun prompts, the writers have naturally learnt many important<br />

writing skills. There are no grades or assessments, and there is a<br />

great deal of room for risk taking.<br />

The young writers have become much more comfortable<br />

trying new ideas and sharing their work, and they have<br />

developed powerful and unique writing voices. I think the<br />

program thrives because this is their community. The space is<br />

safe, supportive, and non-judgemental, and from the moment<br />

they step through the door, these talented young people are<br />

seen as writers, sitting amongst fellow writers and learning from<br />

each other.

One of the biggest highlights for me has been watching the<br />

young writers read their work in public and seeing the effect of<br />

their words on the listeners. I also love how every week these<br />

writers blow me away with their sensitive, funny, and<br />

extraordinarily powerful words. I love how they don’t hesitate to<br />

try new ideas. I admire the fearlessness in their writing, and also<br />

how they face their fears in reading their work out to each<br />

other. And I love how much we laugh every week in our little<br />

community space.<br />

I should also mention there is a school-based <strong>Young</strong><br />

<strong>Writers</strong> program offered by the Centre, where tutors go into<br />

schools to run workshop-based sessions for children aged 12-18.<br />

One such program ran very successfully at Albion Park High<br />

School in 2017. The course ran for ten weeks, and the students<br />

explored both short story and poetry writing, creating a great<br />

deal of interesting work over the term. At the end of the<br />

program, the students submitted their favourite work to the<br />

Centre, and Ron Pretty, the poetry tutor, turned it into a book<br />

which was launched by the students at the school.

Responses to the sculpture<br />

'Love' by Alexander Milov<br />

Image reproduced with permission from French photographer<br />

Gerome Viavant (geromeviavant.com)

The architects used your birth certificate as a blueprint: that’s<br />

why your skeleton looks like scaffolding. I see a glimpse of you<br />

behind the robust, never rusting bars. The remnants of your<br />

handprints are on some of your bones, stubborn and refusing to<br />

fade. Did you build this behemoth, or were you trying to<br />

deconstruct? Sometimes, I think you leave a space between your<br />

ribs so I can stick my hand through and hold your heart, only<br />

we never know when the hole will be plastered. Maybe they will<br />

lay the brick, or maybe your fingers will stain the steel.<br />

we were both caged when we met.<br />

you were almost slender enough to slip through your bars.<br />

i wanted your voice to<br />

stroke me like a paintbrush, and i wanted your fingers to lay<br />

against my neck.<br />

(your touch would taste like peppermint).<br />

when you saw me, you wanted me closer. you wanted to<br />

hear me not from a<br />

distance but from that shallow space beside you, chin resting in<br />

that perfect hollow next to your shoulder.<br />

(my voice would sound like silver).<br />

we wanted to slip from that space between ourselves and<br />

admire each other like mirrors. we wanted to move, to touch, to<br />

tangle.<br />

(but we loved our cages too much to break free).

Somewhere, teenage renegades are falling in love to rebel<br />

anthems and watered-down booze, leaving stories in the bottom<br />

of their boots and growing gardens of somedays and maybes,<br />

knowing perhaps they won’t make it but hell if they aren’t going<br />

to try.<br />

Here, it’s different. There’s the same spark, but it’s<br />

breathing in dirt and crying soil, trapped, like them—the<br />

anxious kids who don’t have somedays, who don’t know the<br />

meaning of maybe, only tomorrow, and it’s hanging on by its<br />

fingertips.<br />

The renegades don’t flinch; they paint their skin in wild<br />

colours and cut their hair or their clothes and shout, ‘I’m alive<br />

and I’m young, I tore off the shackles with my teeth.’ While the<br />

anxious kids make friends with the shadows, and fall in love<br />

with one a.m. because they are still bound with phantom<br />

restraints the powerful put there.<br />

Why do the children with black and white actions get to walk<br />

under the golden sun? Why are we putting stickers on the vests<br />

of children who are learning what men already do? Why are we<br />

not encouraging their rebellion, their desires to do what men do<br />

not? Shouldn’t we tell our infants to explore the empty<br />

moments they will soon encounter in Kindergarten? Shouldn’t<br />

we show them the way to dive into their marvellous brains? We<br />

teach our children to swim at a young age so they don’t use<br />

floaties at age twelve. I am approaching adulthood and I am still<br />

learning to breathe through my own thoughts.

Rufus was awoken by the sound of a crying baby. Why the hell<br />

was there a—<br />

Oh, it was his baby. Damn. He’d forgotten about that.<br />

He glanced across at Jodie, lying beside him in the bed on<br />

her stomach, head tilted to the side so he could see her smooth<br />

cheek. They would be married soon, he suspected. Reaching out<br />

to stroke her face, he tried to smile, but as the baby started<br />

bawling again, the smile slowly drooped.<br />

Goddamn. If only his father could see him now …<br />

Rufus glanced at the clock. It was three a.m. Perfect. As the<br />

baby continued to scream, Rufus occupied himself by trying to<br />

plan Jodie’s eighteenth birthday party.<br />

Hidden love<br />

Pregnant? That couldn’t be. Pregnant? Not me. Not with this<br />

child. No.<br />

I slowly lift up my top to see a small bump, seeing the<br />

bruises and scratches littering a canvas that wasn’t meant to be<br />

drawn on. I put my hand on my stomach, stare at myself in the<br />

mirror and put a hand over my mouth to mask the pitiful sobs.<br />

He can’t know. Not now, not ever. For your sake.<br />

*<br />

The day he found out, it was hit after hit.<br />

Then snap. Pain, and that’s how easy it was—you were gone<br />

forever.

Sit under the yellow lights, old man,<br />

That flicker and blink above you.<br />

Consider your life<br />

Lived, and then spent,<br />

As you ride the train to somewhere.<br />

Hunch your shoulders and sigh, old man—<br />

That’s just the world pressing down<br />

On jaded lungs<br />

That stifle fancies of laughter.<br />

Run your hands through your hair, old man,<br />

But don’t let them wander further—<br />

There’s no time to search<br />

For fire or fuel<br />

In this desert of existence.<br />

Pull your collar over your ears, old man.<br />

Ignore the red-coated children<br />

Who giggle uncontrollably<br />

At knock-knock jokes told wrong.

‘YOU ARE THE BEST HOPE FOR THE SURVIVAL OF THE<br />

HUMAN RACE!’<br />

The training camp sergeant roared at his newest recruits.<br />

The two babies were simultaneously screaming for their<br />

mother and wearing two of the deadliest bio-mechanised suits<br />

of armour ever designed. The sergeant began to roar again.<br />

‘STOP SCREAMING LIKE BABIES, AND START FIGHTING FOR<br />

REAL.’<br />

The two babies screamed louder. The sergeant seemed to<br />

realise his screaming was doing little to help, and in a quiet,<br />

kind manner, approached the babies.<br />

One of the babies reached out, the suit mirroring its action,<br />

and closed its fist around the sergeant’s throat. He began to<br />

gasp, then to turn purple, then to gurgle, before finally falling<br />

silent.<br />

The baby giggled.<br />

I used to look deep into her eyes, face to face. These days, it<br />

seems we are more often back to back, refusing to meet each<br />

other’s gaze. I believe in the soul, and I believed ours were<br />

intertwined. Now, though, my soul is like a little child, wobbling<br />

on its undeveloped feet as it once again learns to walk alone.<br />

I sometimes wonder if our souls miss each other. If, behind<br />

my back, mine is reaching out for hers. I sometimes still feel<br />

that gentle touch, the innocence of young love, blissfully<br />

unaware of the reality that is yet to come.

Two broken cages, sitting amidst the lonely company of nature.<br />

Each with their own sorrows. They sit there, abused and beaten.<br />

By whom? By society. The draining days and nights at the office,<br />

all the hard work. For what? Just to get scolded by the boss, cut<br />

by the files and drowned in their own tears.<br />

Where did the magic of life go? Where did the happiness<br />

and joy go? Where did childhood go? When they were young,<br />

they were told that adulthood was something to look forward to,<br />

so they spent all their time wishing that they were grown up, not<br />

fully appreciating childhood.<br />

Amidst the lonely company of nature sit two broken cages,<br />

wishing to be children again.<br />

In the city centre, most preferred death. Humane morality had<br />

developed entirely separately to the surrounding world—an<br />

isolated ecosystem of ideas. Lives spent in such close proximity<br />

that they began to overlap one another, experienced in unison.<br />

The city centre was collapsing, reaching critical mass of flesh<br />

and bone. The pregnant cowered in darkened valleys between<br />

grim battlements, wagering on the life of another. Losing. Their<br />

debts invariably claimed by the detestable flightless vultures<br />

who crawled along the gutters. Abandoned husks piled along<br />

the walls of alleys until wandering shamans came, uttering<br />

benedictions and spreading holy water, dissolving through<br />

flesh, revealing their fractured scaffolding or the unformed<br />

features of those untouched by the scavengers.

I could feel fists beating, bawling, at the insides of my stomach<br />

again, clawing to get out. I fell to the concrete, cried for help.<br />

But no one came.<br />

I heard a sob, echoing up from within. A familiar raw-voiced<br />

plea for freedom.<br />

The little voice would’ve ripped me apart from the inside—kept<br />

clawing until I was bled dry and he’d drowned in the blood, so I<br />

thrust my hand down my throat.<br />

Tiny hands scaled up my arm, nails digging trenches into my<br />

skin.<br />

I vomited the thing up in a scatter of viscera. Smattered with<br />

blood, sitting atop the pile of organs, was an infant, staring up<br />

blindly at the midday sun, smiling.<br />

He was free; I was rid of him. Yet, in that moment, the wind<br />

whistled through me. Inside, I was hollow.<br />

The nuke<br />

It’s been fifty years since they fired the nuke at us. No one<br />

knows why they did. Maybe we shot first. I can’t remember.<br />

All I know is that sometimes, when someone is affected by<br />

it, they just sit there. They just sit side by side and wait to die.<br />

Sure we could help them, but we would be force feeding<br />

them at this point. No one has time for that. Not even me. The<br />

guy who writes these pages for …<br />

Why do I write them?