34-37 Degrees South - 2023

This anthology from the South Coast Writers Centre presents fresh country poetry from emerging and award-winning local writers.

This anthology from the South Coast Writers Centre presents fresh country poetry from emerging and award-winning local writers.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

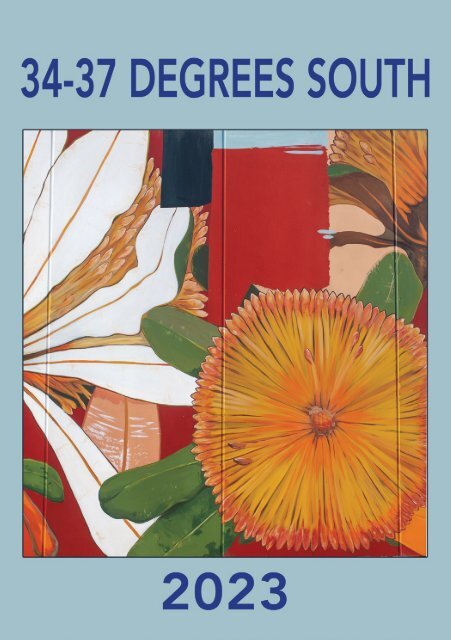

<strong>34</strong>-<strong>37</strong> DEGREES SOUTH<br />

COUNTRY<br />

<strong>2023</strong><br />

An Anthology of Poetry<br />

from the <strong>South</strong> Coast Writers Centre Membership

Published <strong>2023</strong> by <strong>South</strong> Coast Writers Centre, southcoastwriters.org<br />

Copyright © <strong>2023</strong>. All rights reserved. Copyright of individual poems<br />

is retained by the authors.<br />

Cover image: Ash Taylor, Mural Port Kembla 2022 (detail). Part<br />

of the Wonderwalls Project Port Kembla 2022 commissioned by<br />

Wollongong City Council as part of its public art program. The<br />

mural is located on the corner of Wentworth Street and Church Street<br />

Port Kembla. Ash Taylor is a muralist and multi-disciplinary artist<br />

captivated and inspired by the beauty found in Australian landscapes<br />

and our natural environment. http://ashtaylr.com<br />

ISBN: 978-0-9803987-7-9<br />

Photo credits. All photos Peter Frankis except p.1, David Clode<br />

https://unsplash.com/@davidclode<br />

Typesetting: Peter Frankis<br />

Printed: Print Media, Wollongong<br />

ii

Acknowledgement of Country<br />

This publication was produced on unceded Wadi Wadi land and<br />

the poems were written by poets living and working on the unceded<br />

lands of Aboriginal people throughout the <strong>South</strong> Coast, Illawarra and<br />

<strong>South</strong>ern Highlands of NSW and wider parts of Australia. On behalf<br />

of the poets in this edition, the editors acknowledge and pay respect<br />

to the Traditional Custodians and Elders of these lands, our nation’s<br />

first storytellers and poets, and their continued spiritual and cultural<br />

connection to, and custodianship of, Country.<br />

iii

Foreword<br />

Based at Coledale, near Wollongong, the <strong>South</strong> Coast Writers Centre<br />

serves writers and the public between Helensburg and Eden and west<br />

into the <strong>South</strong>ern Highlands (approximately <strong>34</strong> to <strong>37</strong> degrees <strong>South</strong><br />

latitude).<br />

This is the second anthology from poets in the SCWC membership,<br />

focused this year on the theme of Country with poems ranging from<br />

haiku and tanka, through sonnets and free verse to prose poetry.<br />

In this lively collection, I’m pleased to see some of our well-published<br />

poets such as Tim Heffernan, Dr Elanna Herbert and Erin Shiel. Joining<br />

them are newer writers to give the reader a sense of the variety and<br />

diversity of writers working today. The anthology also features a piece<br />

from Ms Fatima Sayed, a Syrian-Australian who we invited to write<br />

about her refugee experience.<br />

Sadly, <strong>2023</strong> saw the passing of Ron Pretty AM, after a long illness.<br />

Ron was instrumental in establishing the SCWC along with Five<br />

Islands Press. He was a remarkable poet and teacher, known to many<br />

in the Illawarra and Australia-wide. The collection closes with a poem<br />

in tribute to Ron’s work from local poet Moira Kirkwood.<br />

I congratulate and thank every poet who submitted to this second<br />

anthology. It is available in both hard-copy and in digital form. In<br />

addition, this year we are bringing you the voices of the poets reading<br />

their work on the website.<br />

I am delighted to present <strong>34</strong> to <strong>37</strong> <strong>Degrees</strong> <strong>South</strong> for <strong>2023</strong>.<br />

Dr Sarah Nicholson<br />

Director, <strong>South</strong> Coast Writers Centre<br />

November <strong>2023</strong><br />

v

Introduction<br />

Between My Country—and the Others—<br />

There is a Sea—<br />

But Flowers—negotiate between us—<br />

As Ministry.<br />

Emily Dickinson, Verse 905<br />

Whatever your politics, however you voted on the Voice Referendum,<br />

country remains a foremost concern to modern Australians, whether it’s<br />

the journey of reconciliation between Australia’s original inhabitants and<br />

a settler society, the tension between urban Australians and the bush, or<br />

finding ways to nurture country in times of global environmental change.<br />

Sometimes country can mean finding a place of comfort; sometimes it<br />

can appear as strange and unfamiliar.<br />

One of the many delights in editing this volume has been enjoying each<br />

poet’s creative response to the theme. Here you’ll find thirty unique<br />

perspectives, ranging from the personal and the intimate to the grand;<br />

poems about trauma, change and hope, and some wry humour too.<br />

The collection is divided into three chapters. ‘You Are Here’ gathers<br />

poems with local concerns: the passing of two beloved chickens,<br />

swimming in the Murrumbidgee River at Wagga Wagga or a salutary<br />

re-take on Dorothea Mackellar’s I Love a Sunburnt Country. The poems<br />

in ‘Voyages’ explore international concerns: returning to a graveyard in<br />

Silesia, learning Spanish at a picnic or remembering a garden in Tokyo.<br />

The final chapter, ‘Inland Empires’, explores more personal issues:<br />

loss, transitions and the body itself as a territory marked by signs and<br />

experience.<br />

vi

The editorial committee, Linda Godfrey, Zohra Aly and Peter Frankis<br />

would like to thank each of the poets who submitted work to this, our<br />

second anthology. To those who were selected, bravo; to those who<br />

missed out this time, keep writing, keep working at this most difficult<br />

craft.<br />

Our thanks also to this year’s reader panel—Linda Albertson, Amelia<br />

Fielden, Kai Jensen and Erin Shiel, who along with the Editorial<br />

Committee read all the submissions and provided clear feedback and<br />

guidance. And a special thanks to Ms Sky Carrall, SCWC’s intern for<br />

this project.<br />

We hope you enjoy reading these poems and also listening to the<br />

poets performing their works and talking about the making of these<br />

poems.<br />

vii

Contents<br />

Acknowledgement of Country<br />

Foreword<br />

Introduction<br />

iii<br />

v<br />

vi<br />

1. YOU ARE HERE 1<br />

walking country Judi Morison 2<br />

By the saltwater lake Alisha Brown 4<br />

at wagga beach Tim Heffernan 5<br />

Country Song Myfanwy Williams 6<br />

Winter solstice Kai Jensen 7<br />

After the fires, January 2020 Melanie Weckert 8<br />

My Country Not My Country Stephen Meyrick 9<br />

Red Joni Braham 12<br />

Funeral birds Alisha Brown 13<br />

“Everyone knows I cry” Linda Albertson 14<br />

(response to Meaghan)<br />

Illawarra Haiku— Lajos Hamers 16<br />

Cardinal Points—Ordinary Lives<br />

She’s Not A Sun-Burnt Country Linda Mcquarrie-Bowerman 18<br />

2. VOYAGES 21<br />

Eggplant Elizabeth Walton 22<br />

Looking for the missing gravestones Elanna Herbert 24<br />

The Country Upstairs Amelia Fielden 26<br />

Go Go Jonathan Cant 28<br />

Princes Highway / Sunset / Winter Elias McKinley 29<br />

water cycle Tim Heffernan 30<br />

After the funeral Linda Albertson 31<br />

Road Trips Brid Morahan 32<br />

Tears of Homeland Fatima Sayed <strong>34</strong><br />

Language swap Stella Hatzis 36<br />

viii

3. INLAND EMPIRES 39<br />

signage Sandra Renew 41<br />

Memento mori with<br />

swallowtail butterflies Erin Shiel 42<br />

Life by the lake Kai Jensen 43<br />

Strange country Kathleen Bleakley 44<br />

‘Life’s a beach, and then you die’ Christine Sykes 46<br />

Country of Mind, Country of Love Janette Dadd 47<br />

My country Bríd Morahan 48<br />

On the poet’s country Moira Kirkwood 50<br />

NOTES ON THE POETS 53<br />

ix

1. YOU ARE HERE<br />

1

walking country<br />

Judi Morison<br />

at the waterhole<br />

feet tread black soil, connect with earth<br />

walaaybaaga ngiyani yanawaanha<br />

we are walking country<br />

we call out to the Old Ones<br />

tell them our names<br />

ask them to guide us<br />

follow bandaarr tracks along the bank<br />

past boundary-markers<br />

—gulabaa, bilaarr, yarraan<br />

past wounds proud on scar trees<br />

that gifted tools the people shaped<br />

—coolamon, shield, canoe<br />

we make a fire and sit<br />

while sweet smoke whispers<br />

welcome home<br />

listen to the creek<br />

hold its breath<br />

as it rests in morning light<br />

until a skein of wood ducks<br />

soars, pulsates<br />

arcs across the sky<br />

2

and opposite, with rippling wake<br />

head up, whiskers dry<br />

gumaay the water-rat hunts<br />

we find his mate downstream<br />

drowned in a cotton-cockey’s yabby trap<br />

walaaybaagabala ngiyani yanawaanha yaluu<br />

still we are walking country<br />

3

By the saltwater lake<br />

Alisha Brown<br />

I stripped like a stonefruit<br />

leaving<br />

only the hard seed<br />

not yet sweet or bitter<br />

ripe or rotten<br />

just a rough, round likeliness<br />

tea trees ached their creaky necks<br />

and, carefully<br />

I dodged the shoremouth spittle<br />

searching for a soft place to be born<br />

or to die<br />

or whatever grace occurs<br />

when things become<br />

my knees found the sand<br />

and it held me<br />

simply<br />

there was silence, and<br />

then sound<br />

blue echoes on the surface<br />

a small fish<br />

me, nameless<br />

and<br />

remaining<br />

4

at wagga beach<br />

Tim Heffernan<br />

on the weekends and after school you went down<br />

to the beach and this was when you were young and<br />

worrying about pubic hair, breasts and dickheads.<br />

it was about a decade since you almost drowned<br />

in the murrumbidgee at hay and well past that<br />

memory of the woman who dragged you up when<br />

you were heading down, downstream. seeking<br />

shade those summers we unfurled our towels under<br />

the red gums down at the beach where the river’s<br />

curve stopped the sand. we walked upstream past<br />

the caravan park to the rocks where we slid into the<br />

river and swam to the other side, swinging on the<br />

rope and jumping from the trees that overhung.<br />

mostly we went with it and floated down to the<br />

beach on tractor tubes or just with our bodies. it<br />

was nice, waiting for the five o’clock wave. a kiss on<br />

the other bank. a glimpse of your breast. walking<br />

you home. it was a place to skim tennis balls.<br />

but then once, across the river where the current<br />

undercut, where we all jumped from the bank into<br />

the river, someone decided to<br />

dive<br />

5

Country Song<br />

Myfanwy Williams<br />

here now on Biripi land<br />

where country hugs<br />

city ravaged soles<br />

into ancient ravines<br />

perched on red gums<br />

black cockatoos sing of<br />

coming rain and later later<br />

sister sings murder<br />

ballads/ First Nations meets Tennessee<br />

and there is something<br />

about grief when sung in language<br />

something about rage<br />

when chanted in hymn.<br />

morning wakes with the kookaburras<br />

the lychees twinkle holy on<br />

their stems red baubles<br />

in post-rain<br />

iridescence.<br />

Note. Biripi land is located on the mid-North Coast of NSW.<br />

6

Winter solstice<br />

Kai Jensen<br />

The calendar’s stuck<br />

on a picture of two crested grebes<br />

courting on a <strong>South</strong> Island lake<br />

June goes on forever<br />

sinking into darkness<br />

the cold deepening<br />

winter doonas, heavy quilts<br />

on the bed and possums<br />

shivering on the front deck<br />

longer by far than the year’s<br />

first five together<br />

this month lingers<br />

hangs about like wood smoke<br />

in the chill night air<br />

when the waves’ drum beats loud<br />

and in the dark of the moon<br />

just above our roof<br />

the galaxy wheels.<br />

7

After the fires, January 2020<br />

Melanie Weckert<br />

Grey tree fringes on the silent hill-corpse<br />

sprout from the pelt of fire slaughtered slopes.<br />

Once green—grasses, bushes, trees<br />

teeming with power and life<br />

the rustle of echidnas, lyre birds, skinks.<br />

Now silent, the brittle charcoaled limbs<br />

the wombat burrows of burnt flesh<br />

singed fur<br />

bones<br />

feathers<br />

beaks.<br />

I recall the agony through aching eyes<br />

of black carcasses plunged from burning sky.<br />

Now, dense undergrowth over hill contours consumed<br />

so bright rocks show through burnt soil skin<br />

above, a lone black cockatoo squeals,<br />

Gone<br />

Gone<br />

Gone.<br />

8

My Country Not My Country<br />

Stephen Meyrick<br />

I<br />

D’harawal country. Stolen country, never ceded.<br />

Ancestors’ country, Spirit country. Story country.<br />

Goanna country; Black Snake country; not whitefella country.<br />

The website says that Cataract Dam’s our heritage.<br />

It notes the barbecues, and that the loos are clean:<br />

‘here you can have a picnic and enjoy the view.’<br />

There is nothing of Captain Wallis, though we know.<br />

About fourteen killed by troopers, though we know.<br />

About the severing of heads, although we know.<br />

Gerontion’s cry: ‘After such knowledge, what forgiveness?’<br />

II<br />

O’Brien’s folk, from County Clare, had English overlords,<br />

five acres and two pigs; they scratched a peasant living—<br />

until the Hunger came. John Frost, the Newport rebel,<br />

was first condemned to death, but (as an act of mercy)<br />

was sent out here in chains; and fifty thousand blackbirds<br />

came as human cargo to cut white sugar cane.<br />

John Grushka fled the Nazis in nineteen-thirty-nine;<br />

Mirjam swam the Elbe, and left a life behind;<br />

Fatima lost a son on Christmas Island’s reef.<br />

Heidegger knew Gerworfenheit must be Dasein’s ground.<br />

9

III<br />

Some came here with intent to plant the Empire’s flag.<br />

Some came to dig for gold or build the Snowy scheme;<br />

to find some space to breathe, or for adventure’s sake.<br />

Their children’s children mine and farm on land that knew<br />

another people’s feet; or squat in cities where<br />

the track is harder to remember than forget.<br />

But love was never bound by right, doled out to each<br />

according to desert. And country’s polyamorous;<br />

she will embrace all those who know and care for her<br />

and hold all kinds of lover in her many-chambered heart.<br />

10

Notes.<br />

The Goanna Man and the Black Snake Woman feature in the story Bah’naga<br />

and Mun’dah told by Auntie Frances Bodkin in the D’harawal Dreaming<br />

Stories series. https://dharawalstories.com/<br />

Captain Wallis led the troopers in the Appin massacre, which took place in<br />

the vicinity of the Cataract Dam.<br />

‘After such knowledge, what forgiveness?’. cf. T.S. Eliot, Gerontion.<br />

Collected Poems: 1909-1962 (2020) Faber and Faber.<br />

Most of the references in this section are to documented individuals. (The<br />

exception is Fatima.) See Conversations with a survivor: John Grushka.<br />

https://sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au/shop/events/survivor-talk/survivor-inconversation-john-grushka/.<br />

Mirjam K. from Monica G. Durrer’s Migrating<br />

Identities Across Time and Space: Life Experiences of East German Migrants to<br />

Australia. PhD thesis, UWA, 2016.<br />

Blackbirds. Between 1863 and 1908, over 50,000 people from Pacific<br />

Island countries were brought to Australia to work in primary industries<br />

in Queensland and NSW. Some were kidnapped and forcibly removed;<br />

many were persuaded to come by promises that were never fulfilled; most<br />

were abused in one way or another; almost one-quarter died. This practice<br />

was referred to as ‘blackbirding’, and the people conducting this trade as<br />

‘blackbirders’.<br />

‘Heidegger claimed Gerworfenheit must be Dasein’s ground.’ Heidegger’s<br />

terms are notoriously difficult to pin down and translate, but Gerworfenheit<br />

is usually translated as ‘thrownness’, meaning that ‘we did not choose that<br />

into which we were sent, yet it forms, shapes, and influences our past,<br />

present, and future’. Dasein is usually translated as Being.<br />

11

Red<br />

Joni Braham<br />

Red as a shearer’s careless nick<br />

on an unsuspecting sheep,<br />

Red as the wool press<br />

waiting for its fill,<br />

Red as the Kelpie<br />

taut and wired for action,<br />

Red as the roustabout’s blood dripping<br />

from a cloven hoof fight back,<br />

Red as the chalk cross<br />

across the next sheep to slaughter,<br />

Red as the dirt stirred through my nostrils.<br />

Red as the blood all over the country,<br />

all over unceded land.<br />

Red.<br />

12

Funeral birds<br />

Alisha Brown<br />

There are six black cockatoos<br />

scattered through the squiggly gum<br />

that homesick siren screech<br />

sharpening my bones<br />

shaking the sun free from its rosy basket<br />

to yolk across the sky<br />

delightfully<br />

I’m not sure why people call them funeral birds<br />

when this is surely a wedding<br />

let me find my abalone earrings<br />

I wish to be an ornament atop morning’s mantelpiece<br />

another lucid dewdrop<br />

teasing colour from everything<br />

God! let me hold all of this –<br />

the birds, the sun<br />

and the crisp significance of it all—<br />

within a finite<br />

sort of intimacy<br />

The cockatoos, they<br />

hop from branch to branch<br />

doing nothing<br />

but the very thing itself<br />

13

“Everyone knows I cry” (response to Meaghan)<br />

Linda Albertson<br />

Let your tears flow.<br />

Let their moisture<br />

revive<br />

the colours<br />

of the spirits<br />

who stir up<br />

your courage.<br />

Your tears mark the path<br />

revealed to you by your ancestors,<br />

who step out with you into<br />

twisting waterways<br />

through Country.<br />

Let each tear<br />

drip<br />

into the cracks of my heart<br />

split<br />

by ignorance<br />

and guilt<br />

and sorrow.<br />

Your heart lets me see you in the waters,<br />

your grace allows me into the waters with you,<br />

to stumble<br />

in your slipstream<br />

as you let the healing flow.<br />

14

Note. Meaghan Holt is a poet, performer (Sassi Spirit) and truth-teller born<br />

on Gunai–Kurni land to an English–Scottish mother and Wakka Wakka–<br />

Pitjara father. Linda first met Meaghan on the lands of the Djiringanj<br />

people and wrote this poem in response to a talk Meaghan gave on her own<br />

Facebook Live which started by Meaghan saying, “Everyone knows I cry.”<br />

15

Illawarra Haiku—Cardinal Points—Ordinary<br />

Lives<br />

Lajos Hamers<br />

northern villages<br />

black diamond’s last sentinel<br />

the dormitory fringe<br />

cartography trains<br />

trace lines of metal & sand<br />

the tides shift the shore<br />

✵ ✵ ✵<br />

escarpment west<br />

spies writer, spies painter, spies muse<br />

veiled untimely dusk<br />

the painter’s hand falls<br />

in the dark tor’s ill shadow<br />

the Berry hills mourn<br />

✵ ✵ ✵<br />

eastern horizons<br />

road, green zone, sand, ocean, sky<br />

clouds punctuate thought<br />

Sandon Point corellas<br />

far from habitat, annoy worms<br />

another migrant tale<br />

✵ ✵ ✵<br />

16

southerly change hints<br />

chill winds & potential harm<br />

un-ceded land<br />

last exit to somewhere<br />

& smeared suburban boundaries<br />

given every latitude<br />

✵ ✵ ✵<br />

17

She’s Not A Sun-Burnt Country<br />

Linda Mcquarrie-Bowerman<br />

she’s a well-fed mongrel dog, a bitsa,<br />

runt of the litter birthed first to a pair of strays<br />

who locked like dingos and stayed that way until one let go<br />

in death: a wave surging and rolling, sacrificing itself<br />

on some shore somewhere with regular monotony;<br />

not fashioned in the shape of one country or another, all flat plains<br />

butted up against softly curving hills descending<br />

into the odd valley or two where rain pisses down, or not, depending on<br />

her seasonal climate, the sun definitely shining (sometimes) out of someplace<br />

south of her border or so some have said, and that tongue<br />

gibbering one language and stumbling over several others<br />

with its unforked flicker.<br />

18

2. VOYAGES

Eggplant<br />

Elizabeth Walton<br />

(after Eggplant, Peter Balakian)<br />

So much wrapped<br />

in the leaves of stuffed cabbage,<br />

the sweetness of late-season love apples, and slow-roasted romas.<br />

My laptop played “Eggplant” in my homeland, my kitchen,<br />

while I sliced mad fruit—<br />

listening to the mussel stock brew—<br />

listening to Balakian’s voice<br />

journey his purpled mood.<br />

I cried at the white dishes on his table—<br />

how the moon looked in that part of the world.<br />

Sunday, I travelled the state, to homelands of old,<br />

for Dad’s birthday. I carefully refrigerated the stock for the soup.<br />

There were no platters at his house anymore<br />

they’ve been given to neighbours,<br />

and grandchildren, who threw them away<br />

before they went overseas. No plans to return.<br />

I arranged the prawns and mirin drenched peaches<br />

22

for the guests on a plate from next door.<br />

Dad did not wait for me to ladle his lunch. He used his<br />

nonagenarian hands.<br />

Note. Peter Balakian’s poem Eggplant, published in New Yorker<br />

May 28, 2018<br />

23

Looking for the missing gravestones<br />

Elanna Herbert<br />

Under the unexpectedly blue sky, canola paints itself across<br />

the horizon to the outside corner of a red cemetery wall at<br />

Tyniec Legnicki village. here, I imagine Kandinsky’s riders<br />

or Marc’s blue horses passing by, heads flicking with<br />

impatience, before the First War put an end to such flagrant<br />

expressionism. but now, in this spring, yellow floods<br />

warmth back to your church, reconfigured for the newcomers’<br />

saints, still – nothing is left of your past, even your church’s<br />

name is gone. yet somewhere, tightly buried here lie the<br />

bones of my ancestors, bundled into soil with the stoic<br />

prayers of a foreign language. inside the cemetery walls<br />

between European trees and knotted ivy, the last<br />

smashed gravestone or a broken granite cross piled to<br />

rubble is all that was left.<br />

“Niet Polskie”.<br />

the head-scarfed grandmother shrugs their absence<br />

asserting her control like a practical boot. beyond her<br />

24

neat white-painted house, those others, long tainted by<br />

war, are left to one side, to fold and slump towards your<br />

soil, as slowly as things of clay and straw and wood are<br />

bound to do. orange tile roofs collapse on themselves, as<br />

once fired ghosts of a European fairy-tale were abandoned<br />

here through fear and disdain. only in this village, where<br />

I am and I am not, can I understand the visceral wound<br />

of contested land, feel unfamiliar shadows as a hollow pit.<br />

this glorious yellow farmland was never my country, but<br />

it was yours. this soil grew thin bones into hope-filled youth<br />

this church washed a wavering soul with divine certainty, until<br />

that moment when you chose life. you changed my history.<br />

you walked away from Gross Tinz. you caught the rigged<br />

ship, and you landed on the edge of a desert, mein Auswanderer.<br />

Note. Tyniec Legnicki is a small village in Lower Silesia, south-western<br />

Poland. Prior to end of the Second World War the village was in Germany<br />

and was named was Groß Tinz.<br />

25

The Country Upstairs<br />

Amelia Fielden<br />

spring-time now<br />

in my other country<br />

the iris<br />

will be winding in bloom<br />

along Meiji Garden’s stream<br />

sixty years since<br />

my hosts took me to that shrine<br />

then Shibuya,<br />

showing off the wonders<br />

of post-war Tokyo<br />

sixty years<br />

exploring from Hokkaido<br />

to Kyushu,<br />

discovering what it is to love<br />

a foreign country<br />

in my southern home<br />

on sleepless nights I count<br />

rosary beads<br />

of natsukashii scents:<br />

new-woven tatami<br />

26

an pillows<br />

drawers of folded kimono<br />

lacquer trays<br />

sushi rice and barley tea,<br />

persimmon globes on black branches<br />

not my country,<br />

not where I will die …<br />

every year<br />

sakura in pale clouds<br />

blossom, fall, scatter<br />

Note. The Country Upstairs by Colin Simpson, 1956, is the author’s<br />

impressions of Japan following World War II<br />

27

Go Go<br />

Jonathan Cant<br />

I FLY west in a Rocket 88,<br />

I take the open road—Route 66<br />

—my freedom ride. I’d escaped from AA,<br />

just enough cash for Mexican XX.<br />

On the highway, Illinois to La La<br />

Land with its tanned band of sand where can-can<br />

dancers in cages do time in Sing Sing.<br />

Such a fan: wish I coulda seen J.J.<br />

Cale play Cocaine or those Texans—ZZ<br />

Top—headline at the Whisky a Go Go<br />

in WeHo on a go-slow, ain’t so-so.<br />

Ah, the clear waters of Bora Bora!<br />

Take me there, or give me Lomaloma.<br />

Catch the seaplane back to Savusavu.<br />

Leave Vanua Levu to write bang-bang<br />

headlines, eat phô soup and sip cold Ba Ba<br />

beer on Old Saigon boulevards. Didi<br />

outta there and home to mama Curl Curl<br />

or south to ski powder at Mount Baw Baw<br />

or north to ride the cane train at Bli Bli—<br />

I have kin there, but no kin in Kin Kin.<br />

Never Never seen the lights at Min Min.<br />

28

Princes Highway / Sunset / Winter<br />

Elias McKinley<br />

on that so-close-yet-so-far<br />

final stretch of highway<br />

between Quaama and Bega<br />

the sunsetting western sky<br />

unironically like a postcard<br />

ablaze in red and umber<br />

set against the cardboard black<br />

of the mountain range’s sharpened silhouette<br />

the majesty<br />

of coming home<br />

29

water cycle<br />

Tim Heffernan<br />

the thing that got me about it was its arrows. the diagram<br />

of the water cycle i learned to draw in high school. it was<br />

perfect too—what went up came down. transpiration<br />

evaporation precipitation—everything was clean again.<br />

water always there and pure. the water cycle had no bottles.<br />

water was storage—out of the cycle, drained from<br />

aquifers by nestlé and left plastic wrapped and shipped<br />

off to countries where water is not a human right. water,<br />

water everywhere and not a supermarket in sight.<br />

30

After the funeral<br />

Linda Albertson<br />

(On viewing Light in the Valley, Lawrence River 2019 by Caroline<br />

Bellamy at Oamaru Art Gallery, Aotearoa New Zealand.)<br />

A special blue<br />

streams over greywacke boulders and rocks,<br />

more than one tone<br />

catches the light beyond mountainous slopes.<br />

A bank of sand<br />

intersects the landscape and pulls the water<br />

towards the dip<br />

where white sheaths angle across distant outcrops.<br />

Under the un-shadowed sky<br />

I wade in the winter water towards a vastness,<br />

my eyes magnetised<br />

by the bleu céleste above an almost invisible<br />

halo where the hard rocks<br />

bruise, where my grief will melt.<br />

31

Road Trips<br />

Brid Morahan<br />

Remember that one when I sang along with the chorus of ‘Flame Trees’<br />

on the AM band, roared it out the open window on the road to Bourke?<br />

Just to keep my spirits up—no aircon in the Datsun<br />

and over fifty in the car.<br />

How about the manic humming, the fog was thick and hazy<br />

on the road from Bright with the heater on full-bore?<br />

Eye-skin peeled back peering into white to avoid hitting the bikes<br />

and going off the edge.<br />

No music on the road from Walgett on dusk with roos all over,<br />

head gasket blown, fuel light on, no water and no phone,<br />

no coverage anyway, seventy-five clicks and busting for a wee<br />

til I made it to the Ridge.<br />

That time I rolled the car on a backroad of Uralla<br />

and stepped out through where the windscreen used to be—<br />

the bush looked the same all round and when you found me, I was walking<br />

the wrong way—back to where I’d come from.<br />

I remember petrol rations—odds and evens on the rego plates,<br />

the locust plague gumming up the grille and the time Snow the cat<br />

jumped out the window on the road to Warrnambool—she was waiting on the<br />

doorstep when I got home two weeks later.<br />

32

The one with the girls: we stopped to pick some cotton outside Narrabri,<br />

picnicked at Sawn Rocks. The songs were swapped for games,<br />

questions big and small, and too many where the answer was ‘George<br />

Bush,’<br />

but so much laughter.<br />

Now I drive the long road south through the Eurobodalla forest.<br />

Wattle stains the air and wind whips the bark off stringys,<br />

I’ve picked up the brandy snaps, the songs are lusty on my lips.<br />

Soon I’ll be dancing to the music,<br />

soon I’ll be back home, with you.<br />

33

Tears of Homeland<br />

Fatima Sayed<br />

The calamities did not stop crushing us, they stabbed us in the heart<br />

of life, the pains became great, and the responsibilities weighed heavily<br />

on our shoulders.<br />

We are a nation that embraced death until we became familiar with it,<br />

and it became part of our daily routine. We are no longer afraid of it.<br />

The war has been going on for more than twelve years, which claimed<br />

millions of lives and has not ended.<br />

Some of the people became displaced, refugees in a country of different<br />

languages, culture, customs, religion, and laws. They missed their<br />

family; some of them left their parents in old age. Parents who had<br />

raised them and still tried to take care of them even at this stage, but<br />

they went, leaving tears and broken hearts.<br />

As for others in inhumane prisons, they faced trumped-up charges<br />

and torture to death, daily. They wished to die a thousand times while<br />

they are alive. The cells are overcrowded, and the number are huge. All<br />

because they demanded freedom from the dictator whose policy was<br />

based on genocide, killing, displacement, compulsory conscription,<br />

and stole the country’s capabilities. This was the price of freedom paid<br />

by the Syrians.<br />

<strong>34</strong><br />

For the people who migrated across the sea their options were limited.<br />

Either death in their home country or death by drowning, facing the<br />

high waves for a better life in Europe. Syrians have become food for<br />

fish, many of them died, and lost in the middle of the sea. The bodies<br />

of children and women were scattered on the beaches, and their<br />

symbol was Ryan

Many Syrians left their homes because of shelling and sniping to live<br />

in worn-out tents for fear of the bombing. Water entered from all<br />

sides, the cold was unbearable, the children’s clothes were wet, and the<br />

mattress was full of water and mud. The children’s dreams became a<br />

heater and a plastic sheet to patch their tent—this in a country rich in<br />

oil resources.<br />

In the end, the Syrians paid the highest price. They sacrificed their<br />

children as martyrs, homes, money, to find freedom away from injustice<br />

and exclusion to live in dignity.<br />

Note. Ryan was Olivia Espie’s five-year old son who drowned after falling<br />

into a swimming pool while on holidays. The pain of loss came rushing back<br />

after seeing images of two young Kurdish brothers washed up on a beach in<br />

Turkey in 2015. They had drowned along with their mother as they made<br />

a desperate bid to escape the violence in Syria. Olivia started a fundraising<br />

drive to help refugees fleeing war-torn countries.<br />

35

Language swap<br />

Stella Hatzis<br />

A sunny day in a week of autumn chill. “I was too sick to cook,” she<br />

apologises, “and I didn’t get to study any Greek.” She leans over the<br />

picnic basket, bumping her straw hat into mine, and produces a bottle.<br />

“I brought milk for... Oh, no.” “For the tea?” “I forgot the tea.”<br />

bright clouds<br />

competing<br />

with white linen<br />

Cake crumbs scatter, shaken off loose sheets of Spanish vocab. The air<br />

smells of orange. “Will you be wanting this back?” I follow her pointing<br />

hand to the cream cheese, freckled with ants in a sticky picnic of<br />

their own. She studies my face. “Want me to teach you how to say<br />

‘damn ants’?”<br />

36

3. INLAND EMPIRES

signage<br />

Sandra Renew<br />

to you, in all our uncharted newness<br />

my lesbian body is freshly inked country,<br />

a tattooed archaeology.<br />

you ask me what happened here?<br />

Queer Queensland happened, gay hate crimes<br />

I am somebody, a body with history.<br />

broken ribs, hips replaced, sun-blemished skin,<br />

scars and marks etch topography,<br />

lay down in palimpsest on skin and bone<br />

vein and nail, a map, an artistry of landscape<br />

my life on record—discovery,<br />

sites and artefacts, evidence in sediment of a time<br />

before us.<br />

a body is signage I say, to help you find<br />

a way through the terrain<br />

to the middle of somewhere<br />

to the heart of us<br />

41

Memento mori with swallowtail butterflies<br />

Erin Shiel<br />

Swallowtails enter the open door and fly<br />

out the window unaware of any walls<br />

or roof. One day they will reclaim it all<br />

and trees will grow through<br />

the floor, their branches prodding the timber<br />

boards until they jemmy the cracks. The rain will teem<br />

through the roof sending shards of terracotta tiles back<br />

to the earth. The swallowtails will polish my bones and shine<br />

my skull as their wings brush through one eye socket and out<br />

of the other. Contented with the quietened world they will<br />

lay eggs in the crevices. From the remnants of my desk<br />

their spindly legs will scatter my dormant words.<br />

Down to the floor of the forest to rot<br />

with the humus and improve<br />

the tilth of the soil.<br />

42

Life by the lake<br />

Kai Jensen<br />

1.<br />

Yesterday we buried Viola, one<br />

of our two old hens, tucking her<br />

orange-feathered body gently<br />

down into the square hole,<br />

nestled on the damp clay layer<br />

that underlies our garden, then<br />

heaped on the topsoil to make a mound.<br />

Today, from my desk, I see that<br />

the joey, freshly out of the pouch, exulting<br />

in its new-found self-locomotion<br />

has made a playground of the grave,<br />

hopping up on to the pile of earth<br />

then down again, over and over<br />

beside its mother snoozing in the sun.<br />

2.<br />

Next day Miranda’s gone too – I find her<br />

keeled over in the straw of the roost box<br />

as though a pecking order and lifelong<br />

married love aren’t so different–<br />

an idea that makes me pause<br />

and think of couples I know.<br />

I fetch the spade, dig Miranda a hole<br />

close to her mate’s, remembering<br />

how they loved to get involved<br />

in garden excavations, so, Hamlet-like,<br />

among other closing remarks, I say:<br />

Okay, now here’s your grave.<br />

The good news is, it has lots of worms;<br />

the bad news, you don’t eat them.<br />

43

Strange country<br />

Kathleen Bleakley<br />

Disenfranchised Stanley is hospitalised: seizure after seizure,<br />

muscles collapsing<br />

he wakes, tries to stand, alarm goes off<br />

they won’t let him walk unaided<br />

There’s been a mistake, it was just a fall<br />

Disoriented<br />

Pearl takes Stanley to the bathroom<br />

no flush - she finds him standing between<br />

door and wall<br />

Stanley tells me he can’t find his way around<br />

this big place full of oddballs.<br />

Dad, I point to the sign above his door:<br />

Mr Stanley Lane<br />

he smiles<br />

Discombobulated What do you think of this place, Stanley asks<br />

I like the gardens and the light, I say<br />

he nods but don’t you think it’s strange?<br />

Distanced<br />

Nurse says Stanley, your wife Pearl and<br />

sister Beth are here<br />

He stands on the other side of the room<br />

Beth has flown across the country<br />

Nurse walks him over, Stanley stares at Beth<br />

44

Disheartened<br />

Stanley is found by Nurse at the servo<br />

Have you seen my wife and dogs?<br />

Moved to the secure ward<br />

seeking his wife and dogs<br />

Stanley gets to the door at the end of the corridor<br />

—won’t open<br />

Dissipated<br />

Disillusioned<br />

Stanley’s stomach growls, roast chicken and<br />

potatoes wafting<br />

his mouth is gummed up, jaw stuck,<br />

it’ll be a pureed lunch<br />

In the courtyard: There’s a fence, you can’t get out<br />

I pick a sprig of lavender, place it in his palm<br />

On the phone: he knows who I am today<br />

How are you?<br />

The food is good but everyone wants to be home<br />

45

‘Life’s a beach, and then you die’<br />

Christine Sykes<br />

Message on a banner: It doesn’t matter where you go in life...<br />

as long as you go to the beach.<br />

Standing on the foamy, driftwood littered shore,<br />

after-storm waves lapping at my ankles,<br />

I imagine a green-aged bottle.<br />

Bobbing in the waves, pushed onto the wet sand,<br />

drawn back into the swell, as if toying with me.<br />

I reach—it disappears under the seventh wave.<br />

The next one drops the bottle at my feet.<br />

Touching the green slime glass. Lifting it to the gleaming sun.<br />

Seeing inside a parchment scroll.<br />

I twist turn the sealed bottle stopper,<br />

wriggle wrestle the paper out and read the Sea Poem.<br />

Message in a bottle: The meaning of life lies between the waves and the<br />

shore.<br />

It is both the beginning of earth and the end. There<br />

in that split second, that infinitesimal space where sea meets land.<br />

Now you see it, now you don’t.<br />

The space shifts constantly moving with each grain of sand.<br />

A whole beach oscillates, becomes hard, yet not fixed.<br />

Water on rock. In the melee of motion,<br />

the instant remains. Pure. Sparkling.<br />

Catch it if you can—see<br />

The depths of darkness. The lightness of being<br />

The infinite in nothing. The lost and the found.<br />

There it is. Now it’s gone.<br />

46

Country of Mind, Country of Love<br />

Janette Dadd<br />

I<br />

In the country of mind currawongs play seed pod maracas<br />

their power beaks of divination freeing seeds of truth.<br />

Faithful apostle birds gather and divide<br />

always the number true, but country changing<br />

so patterns, contours, gradations of experience wear away old<br />

tropes<br />

and new seeds of enlightenment are tended,<br />

held in the quiet centering of being.<br />

II<br />

In the country of love green birds explore the winter garden<br />

dappled light revealing tonal sheen. Sisters together,<br />

no male seen, content in harvesting, investing in futures.<br />

Spring’s epicormic flush sees a bower constructed and bright<br />

eyes tempted<br />

by refracted light of gathered blue, a gambit for one who entered<br />

intrigued<br />

while the others flew, not bound to nest and eggs,<br />

choosing solitary journeys to pursue.<br />

47

My country<br />

Bríd Morahan<br />

Warm breezes swarm to cross blue mountains where splayed gums reach high, skyward<br />

and where once I showered beneath Wentworth’s falls, bathed in the tea-stained pool below,<br />

rich umber from a long-stood pot—beautiful to me, but foreign<br />

Tufted grasses hug the golden rock shelf where yellow sunshine brights Balmoral’s dusky sand<br />

and where once I plunged beneath the kelpy waters, bathed in salty aquamarine with<br />

fallen leaves from drains—vital to me, but strange<br />

Frosted crystals settle over purple fields where hedgerows plump with finches sing and sway.<br />

I late trekked the pebbled shore at Blackpool’s seaside, bathed—just my toes—in granite-grey water,<br />

shadowed by the oil rig, blanching at the cold—familial to me, but dreadful<br />

The holy scree slope stands as sentry to Clew Bay’s silver strands, the vivid green and blue<br />

when sunshine whispers. I late slipped between the rocks, bathed in island’s lee, and the sparkle of the sea<br />

cleared ages from my skin, my breath was sharp like fortress rocks—special to me, but like any oddity<br />

48

In sleep I float above the earth seeing wonder hung in darkness spinning soft and deft on its axle wound<br />

hard edges and soft curving, deep trenches and the blue, cutting land in segments of function, force and form.<br />

I bathe in merest starlight—but all is alien here<br />

From Wentworth Falls, Balmoral Beach, Blackpool and Clew Bay, from all the world and all of space I return—<br />

I go within<br />

I see the ancient peoples, I hear the laughing children, I taste the cod and chips, I smell the peaty soils<br />

I soak in all the waters of lands inside myself:<br />

potch and clay and loam and silt and grit and rock and soil<br />

streams and brooks and rivulets and rivers, lakes and seas<br />

all scour and wash, abrase and rinse<br />

until it is all clear—<br />

my country<br />

49

On the poet’s country<br />

Moira Kirkwood<br />

(in memory of Ron Pretty)<br />

He says: I’m here every day. Moves<br />

easily, anticipates where the land falls<br />

away and when it’ll vanish into cloud.<br />

I don’t think I’m built for this. The bush<br />

crowds me, pushy as a commuter on<br />

a peak-hour bus. My feet whimper.<br />

He asks: What are you working on?<br />

I trust him with my overworked scrap.<br />

He reads but more, he listens. Waits.<br />

For a moment there’s a Presence and<br />

I’m electric. I think about messages<br />

from birds, a smudge of smoke telling on<br />

the horizon.<br />

My teeth chatter, but then he’s talking,<br />

making room so we walk side by side.<br />

I feel oddly, wonderfully grown up.<br />

50

NOTES<br />

ON THE POETS<br />

53

Originally from Aotearoa New Zealand, Linda Albertson has lived<br />

in Bega on the lands of the Djiringanj people for the last twenty-two<br />

years. Her poetry explores family and connection against a backdrop of<br />

reconciling the tension between belonging and the heartache of leaving.<br />

Linda’s poetry has been published by Ginninderra Press and The Canberra<br />

Times.<br />

Kathleen Bleakley lives primarily in Wollongong, second home is<br />

Milton. kb has six published collections (poetry with some prose). Her<br />

latest three: chapbooks, available www.ginninderrapress.com.au<br />

Joni Braham, artist, musician and writer, lives on unceded Dharawal<br />

country. Retirement has opened up wonderful opportunities and time<br />

for writing. Joni’s poetry and short stories have been published and she is<br />

currently navigating the tricky landscape of memoir.<br />

Alisha Brown is a poet and traveller. She won the 2022 Joyce Parkes<br />

Women’s Writing Prize and has featured in Westerly, The Australian Poetry<br />

Anthology, and other major Australian literary publications. You can find<br />

her on Instagram @alishalouisebrown.<br />

Jonathan Cant won the <strong>2023</strong> Banjo Paterson Writing Award for<br />

Contemporary Poetry. His poems have appeared in Cordite, Otoliths and<br />

Live Encounters.<br />

Janette Dadd completed her Bachelor of Fine Arts in February of this<br />

year and held her first solo exhibition in July. She is now working on her<br />

third book of poetry.<br />

54<br />

Amelia Fielden, a professional Japanese translator, mostly writes Japanese<br />

form poetry in English. Her new collection, Adagio Days, was launched<br />

in October.

Lajos Hamers is a storyteller of Hungarian folk tales, writer, actor and<br />

musician. He recently completed a stint as writer in residence at the<br />

SCWC space in the Creative Studios in Wollongong where he began<br />

writing a dramatic monologue about his 25+ years as Santa Claus.<br />

Lajos also recently had a poem published in the Admissions:Voices<br />

within Mental HealthAnthology which formed the basis of an episode<br />

of the A Good Mind To … podcast series.<br />

Stella Hatzis is a lover of all things lexical and has a background in<br />

epic and digital poetry.<br />

Tim Heffernan was born on the Murrumbidgee and moved upstream<br />

to Wagga and Cooma. He now lives in Wollongong. He mostly writes<br />

within these latitudes.<br />

Elanna Herbert lives on Yuin country, NSW <strong>South</strong> Coast. Her<br />

writing appears in numerous literary journals and anthologies.<br />

Elanna’s first book of poetry, sifting fire writing coast, is available<br />

through Walleah Press. Elanna holds a PhD in Communication.<br />

https://elannaherbert.blogspot.com<br />

Kai Jensen has had poems published in many leading Australian and<br />

New Zealand literary journals. Kai lives at Wallaga Lake.<br />

Moira Kirkwood is aiming for one step at a time through the fog.<br />

She has to remind herself to stay humble, grateful and bendy.<br />

Elias McKinley exists in the bush, trying to figure out how to live<br />

in a time of climate crisis. He tries to write poetry. He wishes he<br />

wrote more often, but he writes a lot more than he did when he was<br />

stuck on that city-life treadmill. Sometimes he likes what he writes,<br />

sometimes he’s indifferent. But he always likes how he feels when he<br />

writes.<br />

55

Linda Mcquarrie-Bowerman lives and writes poetry in Lake Tabourie,<br />

NSW. She is completing her Degree in Creative Writing at Curtin<br />

University.<br />

Stephen Meyrick was born in Wales and raised in Perth and now lives<br />

and writes in Wollongong. His work has been shortlisted for the ACU<br />

and Calanthe poetry prizes. His aspiration is to write well-crafted poems<br />

that are accessible to, and can be enjoyed by, a broad audience.<br />

Bríd Morahan is a writer living on the <strong>South</strong> Coast of New <strong>South</strong> Wales,<br />

where she writes, reads, swims and plays.<br />

Judi Morison is a Gamilaroi writer whose work has been published<br />

in various literary journals. She is the recipient of the 2022 Boundless<br />

Indigenous Writer’s Mentorship.<br />

Sandra Renew’s recent poetry collections are Apostles of Anarchy and It’s<br />

the sugar, Sugar, Recent Work Press. The Ruby Red’s Affair, Ginninderra<br />

Press, is a prose/poetry narrative exploded moment. Her web page<br />

is sandrarenew.com<br />

Fatima Sayed was born in Aleppo, Syria. After war broke out she moved<br />

in 2012 to Lebanon with her family. In 2015, she completed a degree in<br />

nursing and began working as nurse. Fatima arrived in Australia 2017<br />

and is now living and working in Wollongong. In 2022, she won first<br />

prize in the Illawarra Multicultural Services Refugee Week Writing<br />

Competition.<br />

56

Erin Shiel won the SCWC Poetry Award in 2022. Her first<br />

collection, Girl on a Corrugated Roof, was published in <strong>2023</strong> by<br />

Recent Work Press. Website: erinshielpoetry.com Instagram: Erin<br />

Shiel (@erinshielpoetry)<br />

Christine Sykes has three published books: her award-winning<br />

memoir, Gough and Me: My Journey from Cabramatta to China and<br />

Beyond and two novels: The Tap Cats of the Sunshine Coast and The<br />

Changing Room.<br />

Elizabeth Walton is a musician and writer working on the<br />

<strong>37</strong> th parallel south. She received the Macquarie University Award<br />

for Academic Excellence in her Masters of Creative Writing and is<br />

completing a Masters of Research and PhD in Creative Writing.<br />

Recent works: WA Poetry Anthology, Swamp, Overland, Guardian,<br />

ABC. Elizabeth received the Anne Edgeworth fellowship in 2022 and<br />

was second place in the 2022 Woollahra Digital Literary award.<br />

Melanie Weckert is a retired environmental microbiologist. She now<br />

lives in Merimbula on the Far <strong>South</strong> Coast of NSW and spends her<br />

time writing poetry and fiction.<br />

Myfanwy Williams is a poet and novelist, who grew up on the <strong>South</strong><br />

Coast of NSW. Her writing explores ecology, conservation, politics<br />

and intergenerational trauma. She is currently working on her first<br />

poetry collection and her second novel. Her Instagram handle is<br />

@writermyf<br />

57

The Editors<br />

Linda Godfrey lives and works on the land of the Wadi Wadi people and<br />

is thankful to be here. She writes prose and poetry, but especially prose<br />

poetry<br />

Zohra Aly is a latent pharmacist whose work been published in various<br />

literary journals and anthologies. She also curates and chairs panels for<br />

writing festivals.<br />

Sky Carrall writes on Dharawal land. She is a UOW creative writing<br />

graduate and facilitates SCWC Young Writers workshops. She is currently<br />

writing a young adult manuscript.<br />

Peter Frankis lives and write on Wadi Wadi land. His first poetry<br />

chapbook, Shorely, was published in 2022 by Ginninderra Press and<br />

his poem 8 ways to look at an octopus was joint winner of the 2022<br />

Wollongong Art Gallery Prize.<br />

58

This anthology from the <strong>South</strong> Coast Writers Centre<br />

presents fresh country poetry from emerging and awardwinning<br />

local writers including: Judi Morison, Alisha<br />

Brown, Tim Heffernan, Myfanwy Williams, Kai Jensen,<br />

Melanie Weckert, Stephen Meyrick, Linda Albertson,<br />

Joni Braham, Lajos Hamers, Linda Mcquarrie-Bowerman,<br />

Elizabeth Walton, Elanna Herbert, Amelia Fielden,<br />

Jonathan Cant, Elias McKinley, Brid Morahan, Fatima<br />

Sayed, Stella Hatzis, Sandra Renew, Erin Shiel, Kathleen<br />

Bleakley, Christine Sykes, Janette Dadd and Moira<br />

Kirkwood.