You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

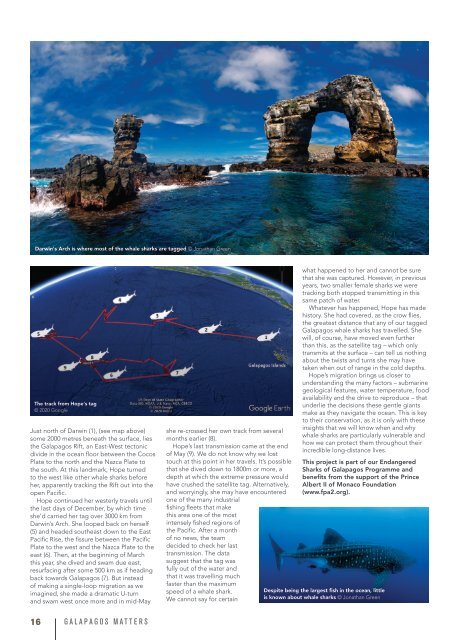

Darwin's Arch is where most of the whale sharks are tagged © Jonathan Green<br />

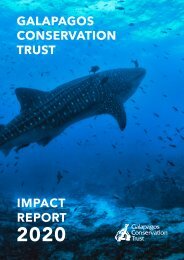

The track from Hope's tag<br />

© <strong>2020</strong> Google<br />

Just north of Darwin (1), (see map above)<br />

some 2000 metres beneath the surface, lies<br />

the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Rift, an East-West tectonic<br />

divide in the ocean floor between the Cocos<br />

Plate to the north and the Nazca Plate to<br />

the south. At this landmark, Hope turned<br />

to the west like other whale sharks before<br />

her, apparently tracking the Rift out into the<br />

open Pacific.<br />

Hope continued her westerly travels until<br />

the last days of December, by which time<br />

she’d carried her tag over 3000 km from<br />

Darwin’s Arch. She looped back on herself<br />

(5) and headed southeast down to the East<br />

Pacific Rise, the fissure between the Pacific<br />

Plate to the west and the Nazca Plate to the<br />

east (6). Then, at the beginning of March<br />

this year, she dived and swam due east,<br />

resurfacing after some 500 km as if heading<br />

back towards <strong>Galapagos</strong> (7). But instead<br />

of making a single-loop migration as we<br />

imagined, she made a dramatic U-turn<br />

and swam west once more and in mid-May<br />

she re-crossed her own track from several<br />

months earlier (8).<br />

Hope’s last transmission came at the end<br />

of May (9). We do not know why we lost<br />

touch at this point in her travels. It’s possible<br />

that she dived down to 1800m or more, a<br />

depth at which the extreme pressure would<br />

have crushed the satellite tag. Alternatively,<br />

and worryingly, she may have encountered<br />

one of the many industrial<br />

fishing fleets that make<br />

this area one of the most<br />

intensely fished regions of<br />

the Pacific. After a month<br />

of no news, the team<br />

decided to check her last<br />

transmission. The data<br />

suggest that the tag was<br />

fully out of the water and<br />

that it was travelling much<br />

faster than the maximum<br />

speed of a whale shark.<br />

We cannot say for certain<br />

what happened to her and cannot be sure<br />

that she was captured. However, in previous<br />

years, two smaller female sharks we were<br />

tracking both stopped transmitting in this<br />

same patch of water.<br />

Whatever has happened, Hope has made<br />

history. She had covered, as the crow flies,<br />

the greatest distance that any of our tagged<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> whale sharks has travelled. She<br />

will, of course, have moved even further<br />

than this, as the satellite tag – which only<br />

transmits at the surface – can tell us nothing<br />

about the twists and turns she may have<br />

taken when out of range in the cold depths.<br />

Hope’s migration brings us closer to<br />

understanding the many factors – submarine<br />

geological features, water temperature, food<br />

availability and the drive to reproduce – that<br />

underlie the decisions these gentle giants<br />

make as they navigate the ocean. This is key<br />

to their conservation, as it is only with these<br />

insights that we will know when and why<br />

whale sharks are particularly vulnerable and<br />

how we can protect them throughout their<br />

incredible long-distance lives.<br />

This project is part of our Endangered<br />

Sharks of <strong>Galapagos</strong> Programme and<br />

benefits from the support of the Prince<br />

Albert II of Monaco Foundation<br />

(www.fpa2.org).<br />

Despite being the largest fish in the ocean, little<br />

is known about whale sharks © Jonathan Green<br />

16 GALAPAGOS MATTERS