Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

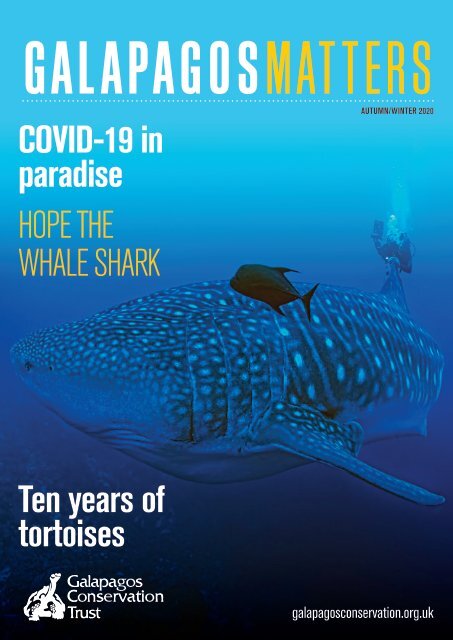

GALAPAGOSMATTERS<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

COVID-19 in<br />

paradise<br />

HOPE THE<br />

WHALE SHARK<br />

Ten years of<br />

tortoises<br />

galapagosconservation.org.uk

GALAPAGOSMATTERS<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Cover<br />

Hope the whale shark was tagged<br />

in autumn 2019 off Darwin’s<br />

Arch in <strong>Galapagos</strong>. She then<br />

travelled more than 3000km<br />

away from the Islands and back,<br />

providing the longest migration<br />

track from a whale shark to date.<br />

Sadly, however, her tag stopped<br />

transmitting in May <strong>2020</strong> in an area<br />

of high industrial fishing effort.<br />

© Jonathan Green<br />

4-5 Wild <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

6 -7 <strong>Galapagos</strong> News<br />

8 -11 The potential cost of the pandemic<br />

With help from some of GCT’s partners and friends,<br />

Clare Simm explores the effects that the COVID-19<br />

lockdown has had in <strong>Galapagos</strong> both for its residents<br />

and wildlife, and what some of the longer-term impacts<br />

might be. The latter includes the risk that invasive<br />

species such as the fly Philornis downsi pose when<br />

not controlled, as Charlotte Causton explains.<br />

12-13 Project Updates<br />

14 UK News<br />

15 -17 Whale shark migration<br />

Whale sharks are known to migrate long distances but<br />

we still have so much to learn about these endangered<br />

fish. However our understanding is increasing thanks to<br />

tagged individuals, such as Hope, whose inspiring, but<br />

sad, story Jonathan Green tells.<br />

18 Growing food at home<br />

While growing vegetables at home has become a hobby<br />

for many of us, in remote places like the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

Islands it is a vital activity. GCT’s Beth Byrne explains<br />

the importance behind one of the new projects that<br />

has grown up out of the pandemic.<br />

19 A decade of tortoise research<br />

The <strong>Galapagos</strong> Tortoise Movement Ecology Programme<br />

turned ten this year. Henry Nicholls interviews project<br />

founder Stephen Blake about what the last decade has<br />

done for tortoise conservation.<br />

20 Global Relevance –<br />

Due to the pandemic, we are more aware than ever<br />

that our wellbeing is linked to that of the environment.<br />

Sharon Deem explores the concept of ‘One Health’,<br />

the idea that the health of people, animals and the<br />

environment are all connected..<br />

21-23 Membership, Reviews, Events<br />

and Merchandise<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Charlotte Causton is a senior<br />

research scientist at the<br />

Charles Darwin Foundation<br />

with extensive experience<br />

in developing methods for<br />

controlling invasive insects in<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong>. She is currently<br />

coordinating an international<br />

effort to develop methods<br />

to control the invasive<br />

avian parasitic fly, Philornis<br />

downsi, which is threatening<br />

many endemic bird species<br />

in the Archipelago.<br />

Jonathan Green is a qualified<br />

naturalist guide, dive master<br />

and elected Fellow of the<br />

Royal Geographical Society<br />

of London who has been<br />

working in <strong>Galapagos</strong> for over<br />

25 years. In 2011, he set up<br />

the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Whale Shark<br />

Project to monitor and study<br />

whale sharks in the Islands.<br />

Having worked in Central<br />

Africa for over 15 years on<br />

a variety of conservation<br />

issues, Stephen Blake<br />

moved to <strong>Galapagos</strong> in 2008.<br />

He established the Giant<br />

Tortoise Movement Ecology<br />

Programme (GTMEP) in 2010<br />

to conduct research on the<br />

movements of<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> tortoises.<br />

Sharon Deem is a wildlife<br />

veterinarian, epidemiologist<br />

and the director of the<br />

Saint Louis Zoo Institute for<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> Medicine. She<br />

has conducted projects in<br />

over 30 counties, including<br />

over a decade of working in<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong>. Much of her work<br />

focuses on diseases shared<br />

between domestic animals,<br />

wildlife and people.<br />

2 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

FROM THE<br />

CHIEF EXECUTIVE<br />

by Sharon Johnson<br />

S<br />

ince the last issue of <strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Matters</strong>, the lives of people living in <strong>Galapagos</strong> have<br />

changed dramatically, like many around the world. In mid-March, the Islands went into<br />

complete lockdown, including an overnight curfew; non-residents were evacuated, and<br />

all conservation fieldwork stopped.<br />

© Sharon Johnson<br />

This has had a huge impact on<br />

the residents’ lives, as you can read<br />

on pages 8-11, as well as on our<br />

projects. We had to adjust fieldwork<br />

and science programmes rapidly,<br />

providing additional support to our<br />

team on the Islands to enable them<br />

to continue their vital work. While<br />

a pause in tourism provided some<br />

respite for the Archipelago’s fragile<br />

ecosystems, it brought economic<br />

hardship for the locals and the risk of<br />

illegal fishing and poaching.<br />

Knowing this is a real threat, and<br />

with support from everyone who<br />

donated to our emergency appeal,<br />

we got straight to work - reworking<br />

our educational and outreach<br />

materials in a bid to stop people<br />

turning to illegal activities; providing<br />

funding for essential PPE to safeguard<br />

locals during food production; and<br />

giving Galapagueños the tools to<br />

grow their own food (p. 18). Thank<br />

you to everyone who donated during<br />

this time.<br />

Our work to fight the impact of<br />

COVID-19 doesn’t stop there. As you<br />

will read on page 17, an immediate<br />

threat to <strong>Galapagos</strong>’ wildlife came<br />

from outside the boundary of<br />

the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Marine Reserve.<br />

An international fishing fleet has<br />

descended, threatening vulnerable<br />

migratory marine species. We are<br />

ramping up our efforts for increased<br />

protection of important migratory<br />

routes, including the creation of<br />

a protected swimway between<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> and Cocos Island, Costa<br />

Rica, which we’ve been supporting<br />

since 2018.<br />

There are other projects that need<br />

our urgent help too. The Mangrove<br />

Finch Project team was evacuated<br />

less than halfway through their field<br />

season, meaning they could not<br />

provide the protection this critically<br />

endangered finch needs against the<br />

invasive fly, Philornis downsi. It is<br />

even more crucial the team returns<br />

to the field in early 2021 to ensure<br />

the survival of the rarest finch in<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> and we need your help<br />

to make this happen (p. 22). On a<br />

more positive note, despite lockdown<br />

cutting short their field work, the Little<br />

Vermilion Flycatcher Project team was<br />

thrilled to find six chicks had hatched<br />

on Santa Cruz in nests that had been<br />

treated for P. downsi (p. 12).<br />

The recent upheaval caused by<br />

the pandemic has meant adjusting<br />

to new ways of working for our UK<br />

staff members too. At the time of<br />

going to press, we are all still working<br />

from home and we are continuing to<br />

re-evaluate how we do things. It is<br />

more important than ever that we stay<br />

in touch with you in ways that work<br />

for you, so please fill in our survey to<br />

let us know how you wish to receive<br />

communications from us in the<br />

future (p. 23).<br />

I will be sad not to see you in<br />

person this year at <strong>Galapagos</strong> Day.<br />

However, we will be running the<br />

event online instead, which I hope<br />

will not only help you remember the<br />

exquisite beauty of the Islands but<br />

it will give you the opportunity to<br />

hear more about what we are doing<br />

to reduce these increasing threats<br />

to <strong>Galapagos</strong>’ unique wildlife. I<br />

very much hope you will be able to<br />

join us (p. 23).<br />

Thank you once again for your<br />

continuing support. It really is<br />

heartwarming to have so many loyal<br />

friends. It has meant so much to us<br />

and, as you will see on the back page,<br />

it has been critically important for our<br />

partners fighting on the frontline of<br />

conservation in <strong>Galapagos</strong>. Thank you<br />

so much from us all.<br />

Sharon Johnson<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Matters</strong> is a copyright biannual publication produced for members of the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>.<br />

The information in this issue was<br />

obtained from various sources, all<br />

ISSN 2050-6074 <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

<strong>Matters</strong> is printed on paper<br />

Designer: The Graphic Design House<br />

Printer: Bishops Printers<br />

of which have extensive knowledge made from well managed forests 020 7399 7440<br />

of <strong>Galapagos</strong>, but neither GCT nor and controlled sources.<br />

gct@gct.org<br />

the contributors are responsible Editor: Henry Nicholls<br />

www.galapagosconservation.org.uk<br />

for the accuracy of the contents or Chief Executive: Sharon Johnson<br />

the opinions expressed herein. Communications and Marketing<br />

Manager: Clare Simm<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

3

4 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

WILD<br />

GALAPAGOS<br />

This <strong>Galapagos</strong> short-eared owl was awaiting GCT<br />

supporter Sarah Ahern on South Plaza island. She recalls<br />

how it appeared completely unphased by their presence,<br />

which is perfectly captured in this stunning image. One of<br />

two endemic owl species on the Islands, the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

short-eared owl is often spotted flying low over lava rocks<br />

and grassland whilst hunting for rats, lava lizards and birds.<br />

Our 2021 calendar is now available for pre-order and<br />

contains this and more incredible photographs from the<br />

<strong>2020</strong> <strong>Galapagos</strong> Photography Competition – find out<br />

more on page 23. Our 2021 competition will be<br />

opening for entries in late October, so don’t forget to<br />

enter your best <strong>Galapagos</strong> images for a chance to win!<br />

© Sarah Ahern<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

5

GALAPAGOS<br />

NEWS<br />

COVID-19 IN<br />

GALAPAGOS<br />

© Nigel Puttick<br />

It was a shock, if not a surprise, when<br />

COVID-19 reached the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

Islands. The World Health Organisation<br />

declared the outbreak of the disease a<br />

pandemic on 11 March <strong>2020</strong> and shortly<br />

after, on 14 March, Ecuador shut its<br />

borders to the world. Flights to <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

were stopped almost immediately but the<br />

country confirmed its first cases on 18<br />

March. A curfew was introduced on the<br />

Islands between 14:00 and 5:00 to try to<br />

reduce the potential spread of the disease<br />

and the Islands went into lockdown. Sadly,<br />

by 23 March the first four cases were<br />

confirmed in <strong>Galapagos</strong> thought to<br />

be residents who had returned from<br />

Guayaquil on the mainland.<br />

There were worries that the fragile health<br />

system on <strong>Galapagos</strong> would be<br />

overwhelmed. Usually anyone with severe<br />

health issues is flown to the mainland.<br />

Thankfully the cases increased slowly. By 10<br />

April, the government reported 10<br />

confirmed cases in <strong>Galapagos</strong> – six on San<br />

Cristobal, three on Santa Cruz and one on<br />

Isabela. Two Galapagueños were also<br />

reported to be ill on the mainland. Of these<br />

12, there were two deaths – one in Santa<br />

Cruz and one on the mainland. By 1 May,<br />

107 cases were confirmed, including 57<br />

cases on three boats moored within the<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> Marine Reserve. Residents from<br />

the mainland were starting to be<br />

repatriated but no one was allowed to<br />

fly without testing negative for the disease.<br />

By 4 June the cases had only risen by<br />

another 14, including cases on another two<br />

boats and accordingly, the curfew was<br />

relaxed to 21:00 – 5:00. Sadly, despite the<br />

precautions being taken, a further case was<br />

found on San Cristobal on 12 June and five<br />

more on Santa Cruz on 18 June in people<br />

who had returned on repatriation flights.<br />

Tourist sites re-opened in mid-July and,<br />

at the time of writing, there are plans for<br />

flights and cruises to resume in<br />

August <strong>2020</strong>, however this is subject<br />

to change.<br />

6 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

© <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park<br />

NEW GNP DIRECTOR<br />

The <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park (GNP)<br />

gained a new director on 1 March <strong>2020</strong>,<br />

Danny Rueda Córdova. An engineer<br />

specialising in socio-economic development<br />

and environment, Mr Rueda has spent 20<br />

years working in protected areas. Over the<br />

last ten years, he was the Director of<br />

Ecosystems for the GNP, responsible<br />

for planning the management of<br />

protected marine and terrestrial areas.<br />

The previous director of the GNP, Jorge<br />

Carrión, is now the Principal Investigator<br />

on our <strong>Galapagos</strong> Tortoise Movement<br />

Ecology Programme.<br />

The new director of the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

National Park Danny Rueda © GNP<br />

ILLEGAL FISHING<br />

26<br />

tonnes of shark fins were seized by<br />

Hong Kong customs officials in May<br />

<strong>2020</strong>, found inside two shipping containers<br />

from Ecuador and thought to be worth<br />

US$1.1 million. This seizure, which included<br />

fins from scalloped hammerhead sharks, is<br />

more than double the 12 tonnes of shark fins<br />

seized in Hong Kong in all of 2019.<br />

This year, researchers have, for the first<br />

time, been able to trace shark fins from the<br />

retail market in Hong Kong back to the<br />

location where the sharks were caught.<br />

Scalloped hammerheads, now critically<br />

endangered, are the most common and<br />

valuable species in the trade. This new<br />

research revealed that the majority of fins<br />

originated in the Eastern Pacific, an area with<br />

a lot of industrial fishing, including fleets<br />

from China. In June <strong>2020</strong>, the arrival of<br />

around 260 Chinese ships, prompted the<br />

Ecuadorian government to look into<br />

improving the protection around <strong>Galapagos</strong>,<br />

including the possibility of increasing the<br />

Ecuadorian Exclusive Economic Zone. This is<br />

a pivotal time for ensuring that key areas get<br />

the protection they need to help conserve<br />

Diego the tortoise back on Española<br />

© Andrés Cruz, GTRI - <strong>Galapagos</strong> Conservancy<br />

DIEGO RETURNS HOME TO ESPAÑOLA<br />

In June <strong>2020</strong>, 15 giant tortoises returned<br />

to Española, the only individuals from this<br />

island to survive centuries of exploitation by<br />

passing mariners. For the past 55 years,<br />

these tortoises were part of a breeding<br />

programme, where they produced more<br />

than 2,000 offspring to save the Chelonoidis<br />

hoodensis species from extinction. Among<br />

the 15 tortoises was the famous Diego who,<br />

after several decades of living at San Diego<br />

Zoo, was returned to <strong>Galapagos</strong> in 1976 to<br />

take part in the breeding programme. At<br />

over 120 years old, he will live out his<br />

retirement on Española with his<br />

descendants who have been released to<br />

the island over the last several decades.<br />

RARE SIGHTING OF RAIL CHICKS<br />

The Charles Darwin Foundation’s<br />

Landbird <strong>Conservation</strong> Group with the<br />

support of the <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park<br />

Directorate undertook a landbird<br />

population census on Santiago island,<br />

including <strong>Galapagos</strong> rails, in February <strong>2020</strong>.<br />

This year the team was lucky to be there at<br />

the height of their breeding season and saw<br />

a number of <strong>Galapagos</strong> rail chicks, which is<br />

rare as they are normally very secretive<br />

birds. Santiago is thought to have the<br />

largest population of <strong>Galapagos</strong> rails in the<br />

Archipelago, and these sightings confirm<br />

that they are doing well on the island.<br />

The <strong>Galapagos</strong> rail is listed as Vulnerable<br />

on the IUCN Red List due to threats<br />

including invasive predators and habitat<br />

destruction. They are found on six islands,<br />

including Santiago, and are locally extinct<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> rail chick on Santiago<br />

© Michael Dvorak, CDF<br />

FERAL CATS POSE A THREAT TO<br />

GALAPAGOS WILDLIFE<br />

New research by Amy McLeod<br />

investigated the threat of feral cats on<br />

San Cristobal to local wildlife. Using GPS<br />

collars to track where these cats were<br />

going, the research found that the cats are<br />

a significant threat to a range of species but<br />

particularly marine iguana hatchlings.<br />

McLeod believes that the cats might also<br />

take advantage of the emergence of<br />

hatchling green turtles. The full paper is<br />

Feral cat with marine iguana hatchling<br />

© Caroline Marmion<br />

NEW LEGISLATION FOR SHARKS<br />

In June <strong>2020</strong>, the Ministry of Production<br />

and Fisheries in Ecuador announced a<br />

multi-pronged approach to protect sharks,<br />

a result for which GCT’s project partner<br />

Dr Alex Hearn has played an integral role.<br />

“Ecuador condemns any act related to<br />

illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing,<br />

especially when these acts are linked to<br />

such a sensitive and important species in<br />

marine ecosystems as the shark,”<br />

announced the Ministry, adding that the<br />

sale and export of five new shark species<br />

will be prohibited, including the critically<br />

HOPE SPOT<br />

A<br />

vital underwater migration highway<br />

that connects the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Marine<br />

Reserve in Ecuador and the Cocos Island<br />

National Park in Costa Rica has been<br />

declared a Mission Blue Hope Spot.<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> has been<br />

supporting the proposed Cocos-<strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

Swimway since 2018 by helping our science<br />

partners gather essential evidence needed<br />

to drive forward the creation of this 120,000<br />

km² area, which is critical for protecting<br />

endangered <strong>Galapagos</strong> marine species<br />

including whale sharks.<br />

galapagosconservation.org.uk/proposed-<br />

protected-swimway-between-galapagos-<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

7

PANDEMIC IN<br />

PARADISE<br />

by Clare Simm<br />

L<br />

ife under COVID-19 has<br />

affected almost everyone<br />

around the world, with huge<br />

swathes of the global population<br />

having gone through some version<br />

of a lockdown, and <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

is no exception. Ecuador shut its<br />

borders and stopped flights to<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> on 16 March, but it<br />

was too late to prevent the virus<br />

reaching the Islands.<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> guide Pablo Valladares was<br />

on his way back from holiday in Nicaragua<br />

when he found himself trapped in Guayaquil,<br />

a city then experiencing an alarming rise in<br />

the number of new coronavirus cases. “We<br />

initially thought that we would get back to<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> within a matter of weeks, but we<br />

were still in Guayaquil more than two months<br />

later,” says Valladares. “In <strong>Galapagos</strong>, we<br />

are used to being active and watching the<br />

amazing wildlife. Even in our backyard, we<br />

have finches, yellow warblers, lava lizards<br />

and racer snakes. In Guayaquil, we were<br />

fortunate to be able to stay with my sister, but<br />

how would we manage confined to a flat in<br />

Ecuador’s second largest city?”<br />

From the windows of the flat, he could<br />

see green hills and a magnificent Ceiba<br />

tree across the street that was a draw for<br />

birds. “One of the things that brought real<br />

happiness was watching red-headed parrots<br />

flying in the morning,” he says. As each<br />

week passed, the longing that Pablo and<br />

his family felt for <strong>Galapagos</strong> grew and grew.<br />

However, they were just some of the 3000<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> residents who had been trapped<br />

on the mainland. “It was only after 68 days<br />

in lockdown that we were allowed to return.<br />

When the plane eventually touched down in<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong>, it was like being born again.”<br />

Thanks to the measures taken by the<br />

Ecuadorian government, the cases of<br />

COVID-19 identified in <strong>Galapagos</strong> did not<br />

overwhelm the fragile medical system on the<br />

Islands. However, lockdown restrictions were<br />

very strict. “Between 2pm to 5am, there was<br />

a total curfew,” says Anne Guezou, GCT’s<br />

Education and Outreach Coordinator who is<br />

based on Santa Cruz. “We had no access to<br />

beaches or the National Park and there were<br />

no flights to the mainland at all. I felt very<br />

restricted,” she says. “Also, there was the<br />

worry that if many people got sick, we were<br />

not equipped to provide intensive care.”<br />

With only a few shops open for food<br />

and other basic supplies, islanders became<br />

more resourceful, with local initiatives and<br />

entrepreneurs springing up to supply the<br />

8 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

© Charlotte Meloy<br />

“Some people<br />

are taking<br />

advantage of<br />

the situation<br />

for their own<br />

benefit.”<br />

View from the flat in Guayaquil that Pablo Valladares<br />

and his family spent their time © Pablo Valladares<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

9

OUR RESPONSE TO THE<br />

IMPACTS OF THE PANDEMIC<br />

With your crucial support, we<br />

ramped up our educational and<br />

outreach activities in a bid to stop<br />

people turning to illegal activities;<br />

we provided funding for essential<br />

PPE to safeguard locals when<br />

producing food; we were able<br />

to continue vital funding of our<br />

ongoing species projects; and we<br />

are doubling our efforts to support<br />

the creation of newly protected<br />

swimways in response to the<br />

threat of industrial fishing fleets on<br />

the boundary of the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

There is a risk that lockdown will have affected the survival of animals such as <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

giant tortoise hatchlings which are threatened by invasive species © GTMEP<br />

community. “Local farmers distributed<br />

products door-to-door and fish was always<br />

available,” says Ainoa Nieto Claudin, wildlife<br />

veterinarian and researcher at the Charles<br />

Darwin Foundation. “Our diet changed<br />

since we were not able to find the same<br />

variety, but also improved as we ate more<br />

local and organic food.” But there was a<br />

dark side to the lockdown too, she notes.<br />

“Violence against women and children<br />

increased dramatically during lockdown,<br />

with a woman killed by her partner in Puerto<br />

Ayora. There have been protests against the<br />

local authorities due to the economic crisis<br />

and some people are taking advantage of the<br />

situation for their own benefit.”<br />

The most widespread impact of the<br />

shutdown, however, has been the interruption<br />

to international tourism, the sector that<br />

underpins the majority of livelihoods in<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong>. “With no tourists we have had<br />

to close our office, our boat is at anchor in<br />

the bay and our employees have no work,”<br />

says Manuel Yepez Revelo, the owner of<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> Sharksky Travel and <strong>Conservation</strong>,<br />

a small tourism company based on San<br />

Cristobal. With the business losing money,<br />

Revelo had to be inventive to make ends<br />

meet. “I started a new business, selling fish<br />

from my scooter house-to-house.”<br />

By mid-June, the incidence of COVID-19<br />

in the Islands had stabilised, the curfew<br />

and other restrictions were easing, and<br />

researchers and conservationists were<br />

beginning to return to work. However, the<br />

interruption to fieldwork could have longterm<br />

impacts on the wildlife of <strong>Galapagos</strong>.<br />

“My main concern is the unknown, and likely<br />

negative, consequences on the survival or<br />

restoration of species or populations such as<br />

the mangrove finch, vermilion flycatcher and<br />

giant tortoise hatchlings. Disruption of data<br />

collection for long-term studies may render<br />

some data sets useless for analysis,” says<br />

Guezou. Disruption to funding streams could<br />

also impact key conservation initiatives,<br />

she says, including the project to restore<br />

Floreana and the research into the impacts<br />

of the invasive parasitic fly Philornis downsi<br />

(see Box).<br />

Another concern is that in the wake of<br />

the virus there could be an increase in<br />

uncontrolled development in an effort to<br />

compensate for lost earnings. “I am afraid<br />

that the pandemic will be used to support<br />

management decisions that will go against<br />

conservation,” says Nieto. In fact, the<br />

upheaval has created new opportunities<br />

that must be seized, she says. “Lockdown<br />

has given us the perfect scenario to start<br />

over and do things better. We need to learn<br />

from our experiences and create new rules<br />

to ensure social and ecological sustainability<br />

for <strong>Galapagos</strong>.”<br />

Birgit Fessl, coordinator of the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

Land Bird <strong>Conservation</strong> Plan at the Charles<br />

Darwin Foundation, agrees that now is the<br />

time to increase protection. “I consider<br />

invasive species to be the biggest threat for<br />

the wildlife in <strong>Galapagos</strong>. More support must<br />

be given to strengthen biosecurity at the<br />

borders of <strong>Galapagos</strong> and stop new species<br />

getting in either by accident or by people<br />

bringing them in.”<br />

For GCT Ambassador Godfrey Merlen,<br />

the absence of the usual human bustle<br />

We need to avoid an increase in unsustainable activities<br />

due to many people losing their jobs © Eva Horvath-Papp<br />

has allowed him to see these Islands in a<br />

way he’s never seen them before. “The sky<br />

has been swept with a deeper blue. The<br />

mangroves stand out with even brighter<br />

greens. The waves crest with a dazzling<br />

white and the crashing sound is louder in<br />

my ears. There is bird song everywhere,”<br />

he says. “The adversity posed by sudden<br />

cessation of the never-ending arrival of<br />

visitors has brought many in the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

community closer to each other and to<br />

the precious natural world around us.”<br />

Now is the time to increase protection<br />

against invasive species such as<br />

blackberry © Ana Mireya Guerrero<br />

10 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

HOW TO CONTROL<br />

A PARASITE<br />

The micro wasp, Conura annulifera, parasitises pupae of Philornis species on mainland Ecuador and is<br />

a potential candidate for use in a biological control program against P. downsi.<br />

© Dave Hansen, UMN<br />

to have completed some trials injecting<br />

a small amount of an insecticide into<br />

the base of the nests where the bloodfeeding<br />

larvae reside when they are not<br />

feeding on the chicks. This work, carried<br />

out by CDF, GNP and the University of<br />

Vienna, has significantly increased the<br />

survival of chicks from four threatened<br />

bird species, including the mangrove<br />

finch and the little vermilion flycatcher.<br />

In collaboration with scientists from<br />

SUNY-ESF and Syracuse University, we are<br />

also investigating whether we can use fly<br />

pheromones and bird odours to lure adult<br />

Philornis flies down from the canopy and<br />

into traps.<br />

All our efforts to control this deadly<br />

parasite require a mix of ingenuity and<br />

perseverance. We are fortunate to be<br />

working with a large group of dedicated<br />

scientists who are not deterred by<br />

setbacks like that posed by COVID-19<br />

and who will continue the work to ensure<br />

the conservation of the unique landbirds<br />

of <strong>Galapagos</strong>.<br />

by Charlotte Causton<br />

As we made preparations for this year’s<br />

fieldwork, the weather was our biggest<br />

concern. Little did we know that there would<br />

be a global pandemic that would shut<br />

down research for three-and-a-half months<br />

in the middle of the bird-breeding season,<br />

a crucial window for testing methods to<br />

control the invasive parasitic fly Philornis<br />

downsi, enemy number one of the smaller<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> landbirds.<br />

These invasive flies, introduced from<br />

mainland Ecuador by accident, are experts at<br />

locating bird nests, where they lay their own<br />

eggs. Once the maggots hatch, they feed<br />

off the blood of young chicks, sometimes<br />

killing an entire brood. To date, P. downsi is<br />

known to attack 21 different landbirds, more<br />

than half of which are species of <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

finch, and is a serious threat to the survival<br />

of at least six species including the critically<br />

endangered mangrove finch. The parasitic<br />

fly also threatens some populations of the<br />

little vermilion flycatcher, the most colourful<br />

landbird in <strong>Galapagos</strong>.<br />

In a race against time, the Charles Darwin<br />

Foundation (CDF) and the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

National Park (GNP) are coordinating a<br />

multi-institutional and multi-country project<br />

to research the biology and ecology of this<br />

little-known fly, with a view to developing<br />

effective, environmentally friendly means<br />

of control. One promising approach is<br />

biological control, which involves introducing<br />

one of the fly’s natural enemies from its<br />

native range to the Archipelago. Exploratory<br />

surveys on mainland Ecuador, led by the<br />

University of Minnesota and CDF, have<br />

identified a small wasp, Conura annulifera,<br />

that is itself a parasite of P. downsi. After five<br />

years of careful work, results indicate that this<br />

wasp is a Philornis specialist. We now have<br />

the go-ahead to bring a small number of<br />

wasps into a quarantine facility in <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

in order to assess whether it is safe to<br />

introduce the wasp to the Islands.<br />

In the meantime, we need to deploy<br />

other tools to protect the nests of those<br />

species at the greatest risk of extinction.<br />

Before COVID-19 brought put an end to<br />

our fieldwork this year, we were fortunate<br />

Philornis downsi larvae feed on the blood<br />

of bird hatchlings, often causing all of the<br />

chicks in a nest to die. © Henri Herrera, CDF<br />

Philornis downsi is one of the key threats<br />

to the critically endangered mangrove<br />

finch. Due to the COVID-19 lockdown, the<br />

Mangrove Finch Project team was not able<br />

to provide the protection that the chicks<br />

needed in the <strong>2020</strong> season, so it is unlikely<br />

that many fledged successfully. We need<br />

to ensure that the team can return in 2021<br />

so that they can combat P. downsi as well<br />

as control the invasive rat population that<br />

is also a threat to the birds. Please help us<br />

to ensure the survival of these rare birds<br />

and the other unique wildlife of <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

by supporting our appeal today.<br />

You can read more about<br />

the appeal on page 22.<br />

Protecting bird hatchlings from P. downsi is difficult because nests are<br />

typically found high up in the tree canopy. © Agustin Gutierrez, CDF<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

11

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

Female little vermilion flycatcher feeding chicks © David Anchundia, CDF<br />

Clearing invasive vegetation from little vermilion flycatcher<br />

breeding areas © Agustin Gutierrez, CDF<br />

L<br />

ast year we featured the striking black and red plumage of the little vermilion flycatcher on<br />

the cover of <strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Matters</strong> (<strong>Autumn</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> 2019 issue), alongside the launch of our<br />

‘Save Darwin’s Birds’ appeal. With your help, the first year of the ‘Saving the Little Vermilion Flycatcher’<br />

project on Santa Cruz has been a great success despite the challenges the team has faced, so<br />

thank you to everyone who supported the project.<br />

It has only been three decades since the little vermilion flycatcher<br />

was a common sight on Santa Cruz. Since then, their numbers have<br />

dramatically decreased with only 40 breeding pairs now found on the<br />

island. In response to these declines, the Charles Darwin Foundation<br />

and the <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park Directorate, in collaboration with<br />

University of Vienna, launched a three-year conservation programme<br />

in 2019. The team identified six plots in key flycatcher habitat to focus<br />

their objectives and help mitigate against the main threats to the<br />

population on Santa Cruz.<br />

Firstly, the team began restoration of the plots to improve access to<br />

vital feeding grounds. The insects crucial for chick rearing are lacking<br />

in areas heavily invaded by plant species like non-native blackberry.<br />

Furthermore, blackberry forms a dense understory leaving few open<br />

areas near the ground for adults to hunt. During the year, local workers<br />

and Park rangers continued to clear areas of invasive blackberry and<br />

sauco plants to allow native, endemic plants to grow freely. This work<br />

demands continuous effort, as invasive plants can quickly reinvade.<br />

Although all activities had to be stopped in March <strong>2020</strong> due to<br />

COVID-19, thankfully four out of the six plots were fully cleared prior<br />

to lockdown, ensuring the birds could benefit from improved hunting<br />

conditions for longer.<br />

Reducing predator pressure via rat control is the team’s second key<br />

objective. After placing bait stations in the six plots last October, only<br />

one nest out of eleven (9%) failed due to predation in comparison to<br />

22% of nests outside of the controlled plots. Further work to verify<br />

these findings will be undertaken during the next field session.<br />

Their final objective is to increase the fledging success of flycatcher<br />

nests. To do this, the team captured and banded ten individual birds,<br />

racked up over 80 hours of nest observations, and treated twelve<br />

nests with insecticide to reduce the impact of the invasive parasitic<br />

fly Philornis downsi (read more on page 11). The team saw the<br />

successful fledging of six chicks from three nests, all of which had<br />

been treated with insecticide. Again, fieldwork was stopped before<br />

the team managed to collect all the data on failed nests meaning<br />

data collection during the 2021 field season is even more important<br />

for these birds.<br />

In just the first year of implementing these conservation actions,<br />

the team has already managed to improve the breeding success<br />

for these beautiful birds compared to previous years, despite<br />

activities being suspended during lockdown. As <strong>Galapagos</strong> relaxes<br />

movement restrictions, scientists are returning to the field as quickly<br />

and safely as possible to resume clearing the plots and monitoring<br />

these vulnerable birds prior to the start of the next breeding<br />

season in November.<br />

12 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

Taking health stats and key measurements of a marine iguana at<br />

La Lobería colony, San Cristobal © Juan Pablo Muñoz-Pérez<br />

INVESTIGATING PLASTIC POLLUTION<br />

THREATS TO MARINE IGUANAS<br />

Marine iguanas are an iconic, endemic species in <strong>Galapagos</strong>,<br />

known for their incredible diving ability to feed on marine algae.<br />

The species are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened<br />

Species; however 10 of 11 subspecies are listed as Endangered or<br />

Critically Endangered. It is estimated that the San Cristobal marine<br />

iguana colony stands at just 400 individuals.<br />

Threats to marine iguanas include El Niño events, where their main<br />

algae diet disappears, and predation by introduced species such as<br />

cats and dogs. From the MV Jessica oil spill in 2001 we also know that<br />

marine iguanas are very sensitive to toxic threats. A study by Martin<br />

Wikelski and colleagues in 2002 found trace amounts of oil pollution<br />

from this spill caused a 62% die off in the Santa Fe colony. However,<br />

more recently, scientists have been asking how plastics and associated<br />

toxins (microplastics often accumulate toxins on their surface) might<br />

be impacting marine iguanas.<br />

A wildlife:plastics risk assessment by our partners at the University of<br />

Exeter identified marine iguanas as high risk for both plastic ingestion<br />

and entanglement. In response to this, between June and September<br />

2019, Jen Jones, GCT’s Head of Programmes and PhD researcher at<br />

the University of Exeter, and Juan Pablo Muñoz-Pérez, Ecuadorian<br />

IDENTIFYING PLASTIC SOURCES,<br />

PATHWAYS AND SINKS<br />

key element of our Plastic Pollution Free <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

A programme is identifying where plastics reaching the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

Islands are coming from, so we can pinpoint the most effective<br />

interventions to reduce the sources of pollution. This needs a<br />

combination of approaches, including predictions from oceanographic<br />

models and checking what is being found on the beaches.<br />

In 2019, research into developing a plastic flow model for<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> began, led by our partner and oceanographer Dr Erik van<br />

Sebille from the University of Utrecht. Early modelling work, together<br />

with beach surveys of plastics by a <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park team,<br />

is giving us the first picture of pollution sources. We now know, in<br />

general terms, that the sources are (in order of scale) likely to be a few<br />

areas of the mainland - mostly northern Peru and southern Ecuador,<br />

marine industries - fishing in particular – and, to a much lesser extent,<br />

from <strong>Galapagos</strong> itself.<br />

These findings support calls for a regional approach to tackling this<br />

issue in the Eastern Pacific to reduce the amount of plastic arriving on<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong>’ coastlines. Thousands of pieces of plastic wash up on the<br />

Islands’ beaches each year. Clean-up trips alone collect about eight<br />

tonnes each year but this is just the tip of the iceberg.<br />

PhD researcher at the University of the Sunshine Coast, undertook<br />

fieldwork to quantify the pollution risk for marine iguanas and provide<br />

recommendations to the <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park (GNP) for ongoing<br />

monitoring and conservation. Key questions include i) whether marine<br />

iguanas are ingesting plastics, ii) if location affects the probability<br />

of micro and macroplastic exposure and ingestion, and iii) whether<br />

plastics affect marine iguana health.<br />

During fieldwork, the team visited ten distinct marine iguana<br />

habitats, covering four sub-species across four islands. Data were<br />

collected to establish a baseline for large plastic items at these sites<br />

(and potential entanglement risk), using methods co-developed with<br />

the GNP rangers and our Plastic Pollution Free <strong>Galapagos</strong> research<br />

network. At each site, food availability was surveyed including any<br />

instances where marine algae interact with plastic (such as with<br />

fishing lines). Faecal samples from 98 marine iguanas were taken<br />

to investigate exposure to plastics in their diet and to complement<br />

comprehensive health surveys of these individuals.<br />

We will compare more pristine, remote sites on Fernandina and<br />

Isabela in the west of the Archipelago to the more polluted sites<br />

on San Cristobal and Floreana, which also face greater pressures<br />

from invasive species. Analysis of the data and samples is currently<br />

underway, and results will feed into a hotspot risk map that will help<br />

to identify the sites in need of priority conservation to ensure marine<br />

iguanas are protected.<br />

Marine iguana (male in the<br />

breeding season) on the<br />

lookout in San Cristobal<br />

© Juan Pablo Muñoz-Pérez<br />

Information from these trips is being supplemented by regular<br />

citizen science and drone-based surveys to help verify the model’s<br />

results and increase the accuracy of future predictions.<br />

We are also undertaking archaeological studies of collected plastic<br />

items, a discipline known as ‘garbology’ where the ‘life history’ of<br />

an item is investigated to strengthen our insight into the item’s<br />

origins and journey to <strong>Galapagos</strong>. Interestingly, local observations<br />

and preliminary studies, led by archaeologist Prof. John Schofield<br />

at the University of York, have reported numerous items with Asian<br />

labels. Erik’s modelling indicates items from continental Asia<br />

would not reach <strong>Galapagos</strong> by ocean currents, so this pollution is<br />

likely originating from a much closer source, probably the fishing<br />

fleets that operate in international waters near <strong>Galapagos</strong>. This is<br />

further supported by the items’ ‘fresh’ appearance (i.e. they were<br />

not at sea for long) and has raised important questions for marine<br />

industry waste management practices.<br />

We are now developing a high-resolution oceanography model<br />

that will, in addition to pinpointing sources more accurately,<br />

show how plastic pollution moves within the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Marine<br />

Reserve once it has arrived. This will help us focus beach cleanup<br />

efforts in a timely manner, minimising risks to wildlife and<br />

removing items before they break into microplastics that can never<br />

be removed. Garbology investigations are scaling up as well,<br />

including developing methods to involve remote citizen scientists<br />

to accelerate analysis into the life histories of items found on<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> beaches.<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

13

UK<br />

NEWS<br />

© Clare Simm<br />

2.6 CHALLENGE<br />

Thank you to everyone<br />

who took part in the 2.6<br />

Challenge on Sunday 26 April<br />

which would have been the day<br />

of the London Marathon. With<br />

your help, we raised over £500!<br />

There were some fantastic<br />

fundraising attempts. GCT<br />

supporter Dougie Poynter<br />

from McFly filmed himself<br />

putting on 26 jumpers, one of<br />

our supporters did 26 volleys,<br />

and another 26 planks in 26<br />

minutes! Nine month old<br />

baby Esther took 26 steps<br />

and Lina, aged 7 (whose mum<br />

works for our tourism partner<br />

Andean Trails), did a 2.6 km<br />

run. She had never run before<br />

but trained specifically for<br />

this challenge!<br />

GUIDED READING SESSION FOR HOME<br />

LEARNING AND TEACHERS<br />

Storytelling is a fantastic way to engage children<br />

in science and conservation. That’s why we have<br />

launched a free six-part guided reading session<br />

designed for readers aged between 7-11. These<br />

resources are for teachers, parents and carers and were<br />

developed by our Education Officer, Sarah Langford,<br />

based on our storybook Marti the Hammerhead Shark: A<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> Journey.<br />

The downloadable pack will give you all the resources<br />

you need to be able to teach, inspire and discuss Marti’s<br />

story with children whether at home or in the classroom.<br />

The book is now available to download for free as part<br />

of the pack, but you can also buy a hard copy through<br />

our online shop. Why not take this opportunity to learn,<br />

together, about the animals that call the waters around<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> home as well as the threats that these species<br />

© Kat Dougal<br />

HOW DO YOU WANT US TO COMMUNICATE WITH YOU?<br />

The pandemic has given us a chance to review the way we work,<br />

and how we communicate with our supporters. With many<br />

people now working at home, and more resources moving online,<br />

we want to give you the opportunity to let us know how you feel<br />

about digital communications. It is important that as many of you as<br />

possible let us know your views – details can be found on the back<br />

GALAPAGOS ON<br />

BBC NEWS<br />

As you will have seen earlier on page 7, around<br />

260 Chinese industrial fishing vessels were spotted<br />

on the edge of the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Marine Reserve in June,<br />

which is a shocking annual occurrence. On 17 July, the<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> Islands featured on the BBC News. President<br />

of the Governing Council of <strong>Galapagos</strong>, Norman Wray,<br />

and our Endangered Sharks of <strong>Galapagos</strong> partner, Dr Alex<br />

Hearn, were interviewed about these ships, and what the<br />

implications might be for vulnerable migratory species such<br />

as whale and hammerhead sharks. They also discussed how<br />

a large percentage of plastic pollution found on the Islands<br />

is of Asian origin, and the fact that these probably came<br />

from the Chinese fleet. You can watch the interviews on<br />

YouTube: youtu.be/b2EGEvxwXJw<br />

14 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

IN PURSUIT<br />

OF HOPE<br />

By Jonathan Green<br />

Tagging a whale shark © Simon Pierce<br />

I<br />

t was dawn off Darwin,<br />

the most northerly of all<br />

the islands in <strong>Galapagos</strong>, as we<br />

prepared for the first dive of the<br />

day on 5 September 2019.<br />

The conditions had not been in our<br />

favour and a powerful southerly current<br />

made the diving conditions difficult,<br />

threatening to pull us away from the<br />

protection of Darwin’s Arch and into the<br />

treacherous open ocean.<br />

Beneath the water, we spread out along<br />

the lava ledges, hugging the rock and<br />

maintaining visual contact, watching and<br />

waiting. Within minutes, the unmistakable<br />

shadow of a whale shark passed over us<br />

from the north. We let go of the wall in<br />

unison, swimming upwards towards the<br />

subadult female and succeeded in attaching<br />

a satellite tag without her even noticing.<br />

Hanging just below the surface, we watched<br />

as the outline of this shark slowly dissolved<br />

before us, taking tag #184027 with her into<br />

the void.<br />

It was almost two weeks later, back in port<br />

and with an internet connection, that we<br />

picked up the signal from this whale shark,<br />

an individual we decided to name Hope.<br />

Shortly after our encounter, she set out on a<br />

route that has now become familiar.<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

15

Darwin's Arch is where most of the whale sharks are tagged © Jonathan Green<br />

The track from Hope's tag<br />

© <strong>2020</strong> Google<br />

Just north of Darwin (1), (see map above)<br />

some 2000 metres beneath the surface, lies<br />

the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Rift, an East-West tectonic<br />

divide in the ocean floor between the Cocos<br />

Plate to the north and the Nazca Plate to<br />

the south. At this landmark, Hope turned<br />

to the west like other whale sharks before<br />

her, apparently tracking the Rift out into the<br />

open Pacific.<br />

Hope continued her westerly travels until<br />

the last days of December, by which time<br />

she’d carried her tag over 3000 km from<br />

Darwin’s Arch. She looped back on herself<br />

(5) and headed southeast down to the East<br />

Pacific Rise, the fissure between the Pacific<br />

Plate to the west and the Nazca Plate to the<br />

east (6). Then, at the beginning of March<br />

this year, she dived and swam due east,<br />

resurfacing after some 500 km as if heading<br />

back towards <strong>Galapagos</strong> (7). But instead<br />

of making a single-loop migration as we<br />

imagined, she made a dramatic U-turn<br />

and swam west once more and in mid-May<br />

she re-crossed her own track from several<br />

months earlier (8).<br />

Hope’s last transmission came at the end<br />

of May (9). We do not know why we lost<br />

touch at this point in her travels. It’s possible<br />

that she dived down to 1800m or more, a<br />

depth at which the extreme pressure would<br />

have crushed the satellite tag. Alternatively,<br />

and worryingly, she may have encountered<br />

one of the many industrial<br />

fishing fleets that make<br />

this area one of the most<br />

intensely fished regions of<br />

the Pacific. After a month<br />

of no news, the team<br />

decided to check her last<br />

transmission. The data<br />

suggest that the tag was<br />

fully out of the water and<br />

that it was travelling much<br />

faster than the maximum<br />

speed of a whale shark.<br />

We cannot say for certain<br />

what happened to her and cannot be sure<br />

that she was captured. However, in previous<br />

years, two smaller female sharks we were<br />

tracking both stopped transmitting in this<br />

same patch of water.<br />

Whatever has happened, Hope has made<br />

history. She had covered, as the crow flies,<br />

the greatest distance that any of our tagged<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> whale sharks has travelled. She<br />

will, of course, have moved even further<br />

than this, as the satellite tag – which only<br />

transmits at the surface – can tell us nothing<br />

about the twists and turns she may have<br />

taken when out of range in the cold depths.<br />

Hope’s migration brings us closer to<br />

understanding the many factors – submarine<br />

geological features, water temperature, food<br />

availability and the drive to reproduce – that<br />

underlie the decisions these gentle giants<br />

make as they navigate the ocean. This is key<br />

to their conservation, as it is only with these<br />

insights that we will know when and why<br />

whale sharks are particularly vulnerable and<br />

how we can protect them throughout their<br />

incredible long-distance lives.<br />

This project is part of our Endangered<br />

Sharks of <strong>Galapagos</strong> Programme and<br />

benefits from the support of the Prince<br />

Albert II of Monaco Foundation<br />

(www.fpa2.org).<br />

Despite being the largest fish in the ocean, little<br />

is known about whale sharks © Jonathan Green<br />

16 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

INDUSTRIAL FISHING<br />

The disappearance earlier this year of Hope captured global<br />

interest, especially as her tag stopped working in an area of high<br />

industrial fishing effort. Every year industrial fishing fleets gather<br />

between the boundary of the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Marine Reserve (GMR)<br />

and the Ecuadorian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) to make the<br />

most of the abundance of fish. There are serious concerns for the<br />

marine wildlife of <strong>Galapagos</strong> as many migratory species, including<br />

whale sharks, leave the safety of the GMR to travel to foraging<br />

and breeding grounds. The arrival of around 260 Chinese fishing<br />

vessels in June <strong>2020</strong> has led to the Ecuadorian government<br />

working on a ‘protection strategy’ for the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Islands,<br />

which could include extending both the EEZ and the GMR to cut<br />

off the corridor of international waters between the two areas.<br />

GCT and our project partners are very much hoping this<br />

becomes a reality and will do everything we can to support<br />

these efforts.<br />

By tagging whale sharks we are starting to understand<br />

where they go, and why © Simon Pierce<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

17

FOOD FOR THOUGHT<br />

by Beth Byrne<br />

Harvesting maracuya (passionfruit) © Ashleigh Klingman<br />

This project is a chance for the family to learn about<br />

gardening together © Ashleigh Klingman<br />

I<br />

n the first few weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown, hundreds<br />

of thousands of people in the UK searched online for advice<br />

on how to start a vegetable patch or grow fruit in containers. At<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>, we were no exception, with several<br />

staff members taking the opportunity to grow tomatoes, courgettes<br />

and other vegetables.<br />

While for many people growing vegetables<br />

at home has become an increasingly popular<br />

hobby, the ability to cultivate your own<br />

food is so much more critical in isolated<br />

places like the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Islands. Due to<br />

the pandemic, residents in <strong>Galapagos</strong> have<br />

been feeling the burden of lost income since<br />

the shutdown of tourism, which makes up<br />

more than 80% of the local economy. The<br />

poverty rate on the Islands will likely climb in<br />

<strong>2020</strong> – before the pandemic 8% of families<br />

were already living below the poverty line –<br />

meaning homegrown food is more critical<br />

than ever.<br />

Hacienda Tranquila, SA (HTSA) “Peaceful<br />

Ranch” is a sustainable agricultural farm<br />

on San Cristobal. They noticed the need<br />

for increased food security and to support<br />

Lecocarpus darwinii © Ashleigh Klingman<br />

local families during this difficult time. 97%<br />

of the Islands is designated as National<br />

Park, which leaves just 3% for community<br />

life including farming, and many families<br />

do not live in homes with accessible green<br />

space. Approximately 75% of the fresh<br />

food consumed in <strong>Galapagos</strong> is imported<br />

from the mainland. With transportation<br />

restrictions in place, access to food has been<br />

increasingly limited and significantly more<br />

expensive.<br />

It is so important to encourage and<br />

support local people as they learn to grow<br />

their own food so they can become selfsufficient.<br />

In addition to the socio-economic<br />

benefits, there is substantial research which<br />

shows that people who connect with nature<br />

as children develop stronger conservation<br />

and sustainability values. They are more<br />

likely to protect the environment when they<br />

grow up. 40% of the 30,000 Galapagueños<br />

are under 15 years old and these young<br />

people are vital for building a culture<br />

of sustainable living and environmental<br />

awareness.<br />

With our project partners HTSA, the<br />

Urban Family Gardening for Tranquillity<br />

<strong>2020</strong> project is using gardening to tackle<br />

food security during COVID-19. The<br />

project will harness HTSA’s skill of building<br />

community through purposeful humannature<br />

interactions and deepen the respect<br />

for nature with local families. It will develop<br />

a network by providing teachers with<br />

educational gardening packs and take this<br />

opportunity to support families while they<br />

adjust to the post-COVID world by helping<br />

them make their patios into a tranquil<br />

garden refuge.<br />

The educational gardening packs<br />

produced will contain fun yoga activity<br />

cards and creative character information<br />

cards that accompany two edible and<br />

two endemic plant seedlings. The project<br />

also looks to promote proper nutrition<br />

and creative cooking with a social media<br />

campaign to improve and vary diets, weekly<br />

recipe webinars and encourage sharing of<br />

recipes to inspire and motivate families. At<br />

the end of the project families will evaluate<br />

how their garden has performed and the<br />

connections they have forged with one<br />

another and nature.<br />

By facilitating the opportunity for families<br />

to grow their own food, we can help<br />

mitigate some of the financial hardship<br />

the <strong>Galapagos</strong> community faces from the<br />

sudden halt in tourism. Also, by increasing<br />

the accessibility of nature, we will inspire<br />

families and instil passion in the future<br />

ambassadors of <strong>Galapagos</strong> for the incredible<br />

wildlife that share their Islands. Without<br />

support and enthusiasm of the people who<br />

live in the Enchanted Isles, how will we ever<br />

be able to protect them?<br />

Cartoon flower and tomatoes produced<br />

for gardening packs © Sai Pathmanathan<br />

18 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

TEN YEARS IN<br />

THE LAND OF<br />

GIANTS<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> giant tortoises on southern flank of Alcedo volcano © GTMEP<br />

The <strong>Galapagos</strong> Tortoise Movement<br />

Ecology Programme (GTMEP) is ten<br />

years old. Henry Nicholls talks to ecologist<br />

Stephen Blake about how the project came<br />

about, what has been achieved over the last<br />

decade and why this work is so important.<br />

GTMEP project founder Steve Blake checks<br />

a tortoise tag © GTMEP<br />

Henry: Before coming to <strong>Galapagos</strong>, you’d<br />

spent much of your career working on forest<br />

elephants in the Congo Basin in central<br />

Africa. Forest elephants and giant tortoises<br />

seem like very different study species but<br />

there are lots of similarities aren’t there?<br />

Steve: Both are megavertebrates. They are<br />

the largest animals by far in their respective<br />

ecosystems. Both are keystone species<br />

and ecosystem engineers that exert an<br />

ecological impact that is disproportionate<br />

to their abundance. They both have very<br />

broad diets, eating well over 100 species of<br />

plant and, when fruit becomes available, will<br />

switch their diets to take advantage of these<br />

high-value foods. Tortoises and elephants<br />

eat way more fruit than any other species in<br />

their ecosystems and with a gut full of seeds,<br />

they plant them widely as they bulldoze<br />

their way through the landscape. That<br />

has important implications for the future<br />

dynamics of the habitats in which they occur.<br />

Henry: When you began the project in 2010,<br />

what did you set out to achieve?<br />

Steve: From Charles Darwin’s observations<br />

and those of park rangers and local farmers,<br />

we knew that there was a seasonal change<br />

in the distribution of tortoises, but we<br />

didn’t know the mechanics, energetics or<br />

evolutionary basis of these movements. I<br />

knew nothing about giant tortoises. I knew<br />

nothing about the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Islands. So,<br />

our initial questions were very simple: do<br />

tortoises on Santa Cruz island undergo longdistance,<br />

seasonal migrations? If they do, who<br />

moves, when, where, how and why?<br />

Henry: What did you find and why is this so<br />

important?<br />

Steve: By tracking individual tortoises<br />

across the landscape on several islands over<br />

many seasons, we now understand much<br />

better how many factors – temperature, the<br />

distribution of food, the location of nesting<br />

sites, the energetics of movement, the health<br />

of the tortoise – all determine the movement<br />

strategy of a tortoise, including whether it is<br />

likely to migrate or not. For some <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

tortoise species, migrations are important for<br />

their continued survival. However, migration<br />

routes can be degraded or even blocked,<br />

particularly on the inhabited islands. We<br />

now have a management hook to work with<br />

farmers, planning committees, local people<br />

and the <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park (GNP) to<br />

minimise potentially negative effects of the<br />

very vibrant economic growth, and land use<br />

changes, which may impact the ecology<br />

of the tortoises.<br />

Henry: What next?<br />

Steve: We’ve now had ten years of building<br />

a research agenda that’s made a successful<br />

contribution to the management, and<br />

therefore conservation, of the <strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

giant tortoises. We have a bit of a platform<br />

now to bring demonstrable technical<br />

knowledge to the table. Importantly, we<br />

have now passed on the mantle of GTMEP<br />

principal investigator to Jorge Carrión, a<br />

highly respected Galapageño who used<br />

to be director of the GNP. We have the<br />

potential to influence big decisions on the<br />

future of <strong>Galapagos</strong> that were unimaginable<br />

to us a decade ago. Hopefully we can help<br />

to integrate the needs of tortoises into the<br />

planning processes that will decide the<br />

ecological and socioeconomic future of<br />

the Archipelago.<br />

The <strong>Galapagos</strong> Tortoise Movement<br />

Ecology Programme is a multi-institutional<br />

collaboration among the Charles Darwin<br />

Foundation, the Max Planck Institute of<br />

Ornithology, the <strong>Galapagos</strong> National Park,<br />

Saint Louis Zoo Institute for <strong>Conservation</strong><br />

Medicine, the Houston Zoo and<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>.<br />

For some<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong><br />

tortoise species,<br />

migrations are<br />

important for their<br />

continued survival<br />

AUTUMN/WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

19

GLOBAL RELEVANCE<br />

ONE HEALTH: IT’S<br />

TIME TO RETHINK<br />

OUR RELATIONSHIP<br />

WITH NATURE<br />

by Sharon L. Deem<br />

I<br />

f there’s one thing that COVID-19 has laid bare,<br />

it’s that we cannot separate human health from<br />

the health of all other life on Earth. The coronavirus,<br />

SARS-CoV-2, is thought to have reached humans<br />

from a bat host, through an intermediary animal<br />

vector probably traded as a source of protein for the<br />

growing human population.<br />

Wildlife, livestock and humans live side by side in <strong>Galapagos</strong> © GTMEP<br />

The pandemic is a real wakeup call, reminding us that the way we<br />

interact with other species and the wider environment matters a lot.<br />

This is the simple message behind One Health, the collaborative<br />

effort of multiple disciplines — working locally, nationally and globally<br />

— to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment.<br />

This movement highlights the health connections of the three arms of<br />

the One Health triad – animals, humans and environments – and asks<br />

us to work together to solve the many health crises of today.<br />

By way of an illustration, I give you Pseudogymnoascus destructans,<br />

a fungus that was first detected in the United States in 2006 that<br />

infected and killed North American bats in their millions. What has<br />

this got to do with human health and wellbeing? Bats control insect<br />

pests, feeding on many species that plague human crops and vectors<br />

like mosquitoes that carry viruses such as West Nile virus and Zika<br />

virus. So, without bats, we may be at increased risk of infectious<br />

diseases and we become more reliant than ever on pesticides. Bats<br />

are also pollinators, with a role in the fertilisation of some 300 fruit<br />

varieties. Indeed, it’s been estimated that the ‘ecosystem services’<br />

provided by bats contribute almost $4 billion to US agriculture<br />

every year. We cannot continue to ignore the web of ecological<br />

connections. Put simply, a healthy planet equates to healthy humans.<br />

In <strong>Galapagos</strong>, as elsewhere, the health of humans, animals and<br />

environments are connected, and we need to pay attention to the<br />

three sides of the triangle. The overuse of antibiotics to treat human<br />

and livestock bacterial infections, for example, allows for strains<br />

of bacteria that are resistant to<br />

antibiotics to evolve. With humans<br />

in <strong>Galapagos</strong> living so close to<br />

protected areas, it’s very likely<br />

that these strains will find their<br />

way into the wider ecosystem,<br />

with consequences that may have<br />

serious negative health impacts on<br />

the endemic wildlife of <strong>Galapagos</strong>,<br />

the livestock species raised on the<br />

Islands, and the human inhabitants<br />

and tourists.<br />

With many of us now living in<br />

cities and away from nature, it is<br />

easy to ignore the importance of<br />

the profound connections between<br />

the health of humans, other species<br />

and the wider environment, but to<br />

do so is to invite a planetary heart<br />

attack. The COVID-19 pandemic<br />

provides the opportunity to reimagine<br />

a post-pandemic future.<br />

We each have a responsibility to<br />

ourselves, our communities and<br />

other species to embrace the One<br />

Health approach to ensure healthy<br />

humans, healthy animals and<br />

healthy environments.<br />

There are many ways to weave One Health into our daily lives.<br />

Buying less and reusing and recycling more will reduce your<br />

ecological footprint in an instant. Eating less meat and sourcing<br />

food from local, sustainable producers will reduce the movement<br />

of plants and animals, and hence the incidence of new zoonoses –<br />

diseases shared between human and non-human animals. Avoiding<br />

toxic chemicals when treating pests will minimise the introduction<br />

of disruptive chemicals into the environment. Picking up litter,<br />

particularly plastic waste, will contribute to the health of the oceans.<br />

And, of course, respecting the air and water on which we all depend<br />

will not only make you healthier, it also may just make you happy.<br />

For more ideas on how to help visit: stlzoo.org/diyconservation<br />

20 GALAPAGOS MATTERS

SUPPORTER PAGE<br />

© Nigel Puttick<br />

E<br />

veryone has been affected this year, with many lives changed owing to the global pandemic. The charity<br />

sector has been hit hard but your support has been overwhelming – even at a time when things will<br />

not be easy for many of you. As staff, we are always struck by your passion for the Islands. Whether recalling<br />

a trip made 30 years ago, planning a possible future trip or, in some cases, having never even set foot in<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong>, the conversations we have with you evoke the same emotions – joy, wonder and affection.<br />

We thought it would be nice to share some of the comments we have received recently, which keep<br />

us going when times are hard. Many of these we have left as anonymous because they echo so many<br />

other similar comments from others. Together we make a strong force for change in <strong>Galapagos</strong> - thank you.<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> sea lion<br />

© Elena Sabella<br />

Glad you are such a dedicated group<br />

of caring people and hope things get<br />

back to normal with your vital work ASAP.<br />

Good luck to you all.<br />

Travelling round the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Islands<br />

was a once in a lifetime experience for<br />

me. I joined <strong>Galapagos</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong><br />

<strong>Trust</strong> on my return and have supported<br />

it ever since. Good luck with everything<br />

you do!<br />

Keep up your excellent work - you are a<br />

brilliant example to us all in terms of how<br />

we should all be protecting our wildlife.<br />

“Having been supporters for<br />

several years, we have decided<br />

that the donations we will<br />

make in the next two years<br />

will be unrestricted – meaning<br />

that you can spend the money<br />

according to your most<br />

pressing needs. We believe<br />

that this type of flexible support<br />

is vital for charities in<br />

these uncertain times.“<br />

Aurum Charitable <strong>Trust</strong><br />

Hoping to revisit that magical place<br />

one day.<br />

I am a member but want to donate this<br />

small amount to help you keep up the<br />

good work.<br />

Hoping that you and your families will<br />

stay well and safe, and thinking of those<br />

on the Islands who are ill. Wishing and<br />

hoping they recover and thrive.<br />

Lucky enough to have visited - an<br />

amazing group of islands - will live in my<br />

memory for ever!<br />

In these challenging socially-distanced<br />

times, The Evolution Education <strong>Trust</strong><br />

is delighted to be able to offer a grant<br />

to help GCT develop and deliver vital<br />

nature conservation education to<br />

children on the Islands.<br />

Dr Chris Lennard, Acting CEO,<br />

Evolution Education <strong>Trust</strong><br />

I was hoping to fulfil a lifetime’s ambition<br />

and visit this year. Obviously, that’s not<br />

happened so hopefully this donation will<br />

help the Islands stay safe so I can visit in<br />

the future.<br />

A critical time for the <strong>Galapagos</strong> Islands<br />

and for GCT.<br />

Blue-footed boobies<br />

© Mia Taylor<br />

“I was very grateful to<br />

receive your magazine<br />

which really cheered me<br />

up during this strange time.<br />

Consequently, I bought<br />

one of your lovely t-shirts.”<br />

Waved albatrosses<br />

© Jose Rui da Cruz Moura Santos<br />

The overwhelming sense we get<br />

from people who have visited<br />

<strong>Galapagos</strong> is that the experience<br />