Romulus 2018

Wolfson's Literary magazine Romulus

Wolfson's Literary magazine Romulus

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

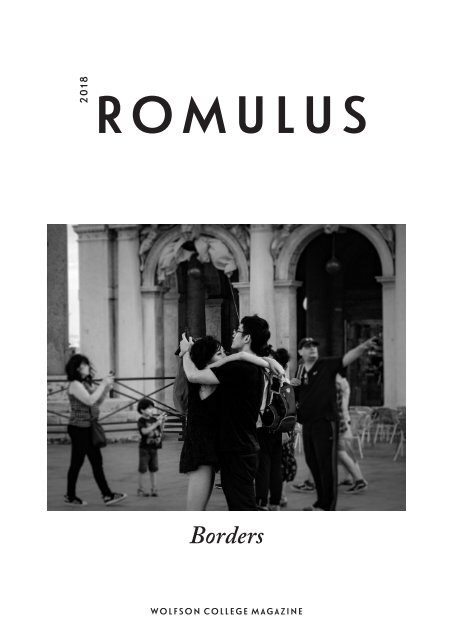

<strong>2018</strong><br />

ROMULUS<br />

Borders<br />

WOLFSON COLLEGE MAGAZINE

CONTENTS<br />

Editorial Board’s Column<br />

Lorenzo Petralia, ‘Dreaming Barbwire’<br />

Interview with Tim Hitchens<br />

Lisa Heida, ‘Sammy’.<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

11<br />

Nicholas Pierpan, ‘The Swells’.<br />

Yasser Khan, ‘Nothing Is Harder on the Soul,<br />

Than the Smell of Dreams, While They Are Evaporating.’<br />

- Mahmoud Darwish<br />

Emese Végh ,“Crossing Borders in Hungary<br />

During the Communist Era”<br />

Lorenzo Petralia, ‘See You on the Other Side’<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

17<br />

ALESSANDRO VATRI, ‘NO SIGNAL’. Taken in Venice, 2016.<br />

Even though a man and a woman are as physically close as they can be in<br />

public, technology creates a border between each individual, as well as the<br />

place they are in.<br />

Yasser Kahn, ‘And I Tell Myself,<br />

a Moon Will Rise from My Darkness’<br />

- Mahmoud Darwish<br />

Eduardo Paredes Ocampo, “Two Poems”<br />

David Yuxin Wang, ‘Zero Hour’<br />

Alessandro Vatri, ‘The Wall’.<br />

Asmi Khushi, ‘Do I Draw Borders Around Myself ?’<br />

Álex Sartoris, “Like the Human Heart”<br />

Cristina Blanco Sío-López, ‘The Warping of Winds’<br />

Yasser Khan, ”A Person Can Only Be Born in One Place.<br />

However He May Die Several Times Elsewhere: In the Exiles and<br />

Prisons, and in a Homeland Transformed by the Occupation and<br />

Oppression into a Nightmare.”- Mahmoud Darwish<br />

Merryn Williams, ‘On the Towpath’<br />

Lisa Heida, Editor of <strong>Romulus</strong>, in Conversation with Sabira Yameen<br />

“It’s like I Am Being Punished for Just Being Deaf ”<br />

Lorenzo Petralia, ‘On the Same Side’<br />

Rebekah Vince, ‘Frontline Love’<br />

Alessandro Vatri, ‘Lost’<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

26<br />

28<br />

29<br />

30<br />

35<br />

35<br />

36<br />

2

Editorial Board’s Column<br />

The editorial team of <strong>Romulus</strong> consists of people from six different countries with<br />

diverse cultural backgrounds, and each person is embedded in different academic<br />

disciplines. Yet we have all shared the same experience over the past several<br />

years: cultural and political practices of protectionism, austerity and resurging<br />

nationalism have re-erected and deepened borders between people. When we<br />

chose the topic of ‘borders’ for this year’s edition of our literary magazine, we<br />

thought of the brutality people face in the US-Mexican border territory, in which<br />

over four-hundred migrants died last year alone trying to cross the fence, the<br />

desert and the Rio Grande. Other similar border conflicts immediately comes<br />

to mind, be it the ongoing struggle of refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea<br />

or those stranded in Calais hoping to reach Great Britain. With Brexit looming<br />

over all our lives, another border inside Europe has been assertively redrawn with<br />

unpredictable consequences.<br />

Paradoxically, we noted that we also live in a time that carries the promise of<br />

boundless, borderless connections through technology, social media and global<br />

mobility. Travelling around the world and communicating with people near and<br />

far has never been easier and more accessible than it is now. If you belong to<br />

the privileged group of young, well-educated and sometimes even well funded<br />

academics, then crossing borders, both the literal kind between countries and,<br />

more figuratively speaking, between disciplines and contexts, is expected and<br />

encouraged.<br />

However, in the midst of all that border-crossing, networking and connecting,<br />

a deep sense of loneliness and isolation often grows. We chose our cover piece<br />

because it so poignantly shows how that which connects us can also separate us –<br />

the very definition of what a border is.<br />

We are grateful to Wolfson College for giving us the opportunity to explore the<br />

paradoxical character of borders in our magazine. We firmly believe that academics<br />

as well as artists ought to make seen that which is hiding in plain sight, not simply<br />

recording and reproducing the visible, but, as the painter Paul Klee famously said,<br />

making things visible. The borders we encounter might sometimes be structures<br />

made from concrete and barbed wire, but often they are immaterial. They take<br />

shape in our institutions, our work and family life and in what we imagine to be<br />

our most private moments. Through images and poems, essays and short stories,<br />

<strong>Romulus</strong> depicts and dissects borders as a multi-facetted phenomenon.<br />

Faced with the reconstruction of borders we had hoped to cross and overcome<br />

for good, affecting all of our lives, we hope to contribute in some way to a critical<br />

and creative engagement with the borders both in and around us.<br />

Lorenzo Petralia, ‘Dreaming Barbwire’<br />

EDITORIAL BOARD:<br />

Eduardo Paredes Ocampo<br />

Emese Végh<br />

Lisa Heida<br />

Laura González Salmerón<br />

Gesa Jessen<br />

GRAPHIC DESIGN:<br />

Agnese Tauriņa<br />

PROOFREADING:<br />

John Francis Davis<br />

4 5

INTERVIEW WITH TIM HITCHENS<br />

Tim Hitchens, President of Wolfson College, might be the most eminent person to talk to<br />

about borders. He served as Chief Executive of the Commonwealth Summit Unit, after<br />

being Director-General, Economic and Consular at the Foreign and Commonwealth<br />

Office. He has over thirty years of experience as a diplomat, which has taken him to parts<br />

of the world as diverse as Pakistan and Afghanistan. Most recently he spent four years as<br />

British Ambassador to Tokyo. We talk about the international character of Wolfson College<br />

and, unavoidably, Brexit.<br />

“Life is not about<br />

solving things forever;<br />

it is about creating<br />

the conditions for peace<br />

so ordinary life can get on<br />

while you deal decently<br />

and in a civilized manner<br />

with disagreement.”<br />

<strong>Romulus</strong> in conversation<br />

with Tim Hitchens, President of Wolfson College<br />

You have spent a great part of your professional<br />

life working in the diplomatic service, how does<br />

your experience on the field translate into your<br />

work at Wolfson, the College being known for<br />

its international community? And on the same<br />

note, yesterday The Guardian published a note<br />

on the University of Oxford’s failure to improve<br />

diversity among students. What do you think of<br />

this?<br />

I think that particularly in these Brexit times,<br />

it’s even more important that Oxford is open<br />

and international. Maybe the reason why the<br />

College elected me was precisely because they<br />

wanted somebody who brings that international<br />

experience. Certainly, I’ve worked in diplomatic<br />

service for 35 years, and I see every issue and<br />

every problem from its international dimension.<br />

I find it difficult not to do that. What I hope<br />

to bring to the job therefore is openness to the<br />

international dimension. By that I mean seeing<br />

every issue from several sides. Seeing it from the<br />

side of the UK, and seeing it from the side of<br />

the rest of the world. I think that is probably<br />

what I will contribute.<br />

On the question of Oxford and access, clearly<br />

we in Wolfson are, if we focus on the graduate<br />

level, in a rather different situation. The whole<br />

access debate is one that is primarily UK-focused<br />

and focused on the question of undergraduate<br />

entry. To an extent we are on the sideline, but it<br />

does affect the reputation of Oxford as a whole.<br />

I think there is quite a lot to be said. On the<br />

positive side about a College like Wolfson, it has<br />

a range of diversity, in terms of nationality,<br />

gender, and ethnicity, which looks and feels very<br />

different from a number of other Oxford colleges.<br />

Nevertheless, I think we do have things we can<br />

bring to debate. For example, we don’t have any<br />

data on the socioeconomic background on our<br />

students; should we be considering that?<br />

But I’m very pleased that here in our college we<br />

look like the world; and that is what Wolfson<br />

was intended to do.<br />

The relations between the countries where you<br />

have worked and Britain have not always been<br />

as cordial as they are now. What is your stand on<br />

topics like colonial reparation? Do you think that<br />

Britain, through fields such as foreign diplomacy<br />

and academia, has addressed these topics?<br />

I think that there is no doubt that the Britain,<br />

which foreign ministry I joined in 1983, fills<br />

a very different place now from then. In 35<br />

years, we have moved on an enormous amount.<br />

There has been recognition by successive British<br />

governments that the experience of colonialism<br />

was in most cases traumatic. And I think it<br />

is fair to say that there are some countries<br />

where we have moved on from that debate<br />

and where we have a very healthy 21st century<br />

relationship. I know Nigeria and Ghana very<br />

well and what happened in the 20th and 19th<br />

centuries is pretty irrelevant to our current<br />

relationship. There are other countries where<br />

history still weighs heavily it all depends on<br />

your perspective. You bring either baggage or<br />

responsibility to the relationship, and we still<br />

have a lot of work to do to work these things<br />

through to their conclusion.<br />

It’s an interesting academic question, how long<br />

it takes before something “becomes history”.<br />

I think Britain probably consigns things to<br />

history quite quickly; in other countries history<br />

will become history after a rather long period.<br />

Often the most difficult relationships are those<br />

6 7

where our sense of how far back history goes is<br />

different. It always used to be said that Britain<br />

knew very little of the history of the Republic<br />

of Ireland, and that the Republic of Ireland<br />

knew rather too much. That produced some of<br />

the differences. And yet in my career, during<br />

the last 35 years, the relationship between<br />

the Republic of Ireland and the UK has been<br />

utterly transformed. So I tend to be optimistic<br />

about the direction. Yet it’s really important as a<br />

country like the UK never to brush history and<br />

the colonial era under the carpet, because it does<br />

still have a major impact upon the way relations<br />

are seen. If you think about our relationship<br />

with Kenya, you cannot separate that from the<br />

historical experience.<br />

You mentioned Nigeria and Ghana, and that<br />

what happened is irrelevant to our current<br />

relationship with these countries, but there are<br />

also other countries that feel more resentment.<br />

I would say that there’s much more complexity<br />

in those relationships. For example, if one looks<br />

at Zimbabwe, there’s still an awful lot of history<br />

that affects that relationship. I think that clearly<br />

Argentina is a country where we moved into<br />

a significant new relationship, but you can’t<br />

pretend that we haven’t had complex relations<br />

quite recently. Ironically, if you go even further<br />

back, Argentina is probably the country in Latin<br />

America that Britain is closest to and most like,<br />

in some ways, but that more modern experience<br />

is there. For the last year and a half I have been<br />

working on a lot of Caribbean countries, and<br />

relations with Western Union countries are still<br />

very much linked to the colonial experiences. I<br />

would also say that for a lot of these countries,<br />

particularly in the Caribbean, it was Britain’s<br />

decision to join the European Union that caused<br />

one of the biggest ruptures in our relationship,<br />

rather than things that happened even further<br />

back. History can be 1973-history.<br />

It was said that one of the positive things of<br />

Brexit was that there is going to be a stronger<br />

connection with countries of the Common Wealth<br />

and the Caribbean.<br />

It was certainly one of the lines given by<br />

the Brexiteers that this would open up new<br />

opportunities, and it definitely does; but if<br />

you look at Britain’s trade with the rest of the<br />

European Union, it’s about 40-50% of our<br />

trade, whilst Britain’s trade with the whole of<br />

the Common Wealth is about 8-10%, so they<br />

are very different kind of relationships.<br />

There is a border conflict that stems directly<br />

from the colonial past. Recently it has flared up<br />

again. I’m talking about the tension between<br />

Israel and Palestine. Do you think that Britain’s<br />

involvement has been sufficient (historically and<br />

present) in addressing the conflict?<br />

There are many people who would say that<br />

Britain’s involvement was too large in certain<br />

areas! All I can say is that I think our position<br />

at the moment, the British position -on the case<br />

of the two-state solution, and that there should<br />

be no resolution of the status of Jerusalem until<br />

the broader issues are settled- that seems to be<br />

absolutely the right kind of position, because it<br />

reflects the broad consensus in the region across<br />

the key parties. The former British foreign<br />

secretary, Peter Carrington, once said to me<br />

that there are a number of issues in the world<br />

that aren’t going to be resolved this year or next<br />

year; they feel utterly intractable, but a time will<br />

come when the stars will align, and they’ll be<br />

open to change. And you need to be ready and<br />

prepared for that moment. It has always felt to<br />

me like the Middle East peace process between<br />

Israel-Palestine is one of those that none of us<br />

can see a way through, this year or this decade.<br />

But there will come a time, and we need to keep<br />

on being ready for that time. I don’t know when<br />

that time will come, but it will be absolutely<br />

critical that we take hold of it when it comes.<br />

What does being prepared mean?<br />

Being prepared means investing in knowledge<br />

so that you keep on being in touch with the key<br />

players. We should stay close to the Palestinian<br />

key players, and the Israeli authorities. And we<br />

should remain influential in the US. Those are<br />

the ways you remain active. Keep on having<br />

seminars and policy-making discussions to<br />

think of ways you could work it through.<br />

Another one of those tense, long-term conflicts<br />

is the one between India and Pakistan, which<br />

at the moment feels like a relationship that is<br />

always blocked, but there will come a moment<br />

when the stars will align and you need to be<br />

invested in both of those countries and their<br />

opinion-formers to be able to move.<br />

It’s interesting to think about this alignment of<br />

stars in a conflict that has lasted not only since the<br />

colonial past, but also since biblical times.<br />

Well, I think there are definitely academics<br />

who quite rightly say that you never solve an<br />

international relations problem. You allow the<br />

friction to exist in peace until it blows up again.<br />

If you look at the experience of the last 300<br />

years, there are very few problems that have<br />

been solved forever. But life is not about solving<br />

things forever, it is about creating the conditions<br />

for peace so ordinary life can get on while you<br />

deal decently and in a civilized manner with<br />

disagreement.<br />

The great part about a college environment like<br />

ours is that there are people from Palestine, from<br />

Mexico, from everywhere in the world, and<br />

each person will bring their own interests and<br />

concerns. You can listen to their concerns and<br />

allow them to speak freely. Give them the space<br />

to express their views, but also bring opposing<br />

views together in this safe environment, which<br />

is a college. People should be allowed to say<br />

things that they probably couldn’t say on the TV<br />

or the radio. I do think that there’s a problem at<br />

the moment where there are lots of things we<br />

are not allowed to say in public because you’re<br />

criticized for saying them. And we need to get<br />

better at creating a space for people to express<br />

strong views. In some ways, the Brexit debate<br />

did show that if people are not allowed to say<br />

certain things, pressure builds up inside the<br />

system, which will erupt in unexpected ways.<br />

What is interesting is that the alt-right<br />

movement was saying the same thing. It is true<br />

that there is a call from many interest groups in<br />

this society for more freedom of speech, complains<br />

about democracy creating its own auto censor...<br />

There is an interesting quote by the philosopher<br />

Kierkegaard, who talks about the freedom of<br />

thought, which is more important than the<br />

freedom of speech. We need at least for our own<br />

heads to be able to think freely, even if we can’t<br />

always speak freely. A friend of mine in Pakistan<br />

said they have freedom of speech, but what they<br />

don’t have, is freedom from not being arrested<br />

immediately after exercising their freedom of<br />

speech.<br />

To anchor the issue more in a context closer<br />

to home: What is your stand on Brexit as the<br />

President of Wolfson, and what would you say<br />

to the people who are going to be affected by yet<br />

another border?<br />

This is quite difficult for me to answer, because<br />

I’m coming from a background of working<br />

35 years for the government. My practice has<br />

always been not to say anything that disagrees<br />

with the government. This is producing a real<br />

challenge for our beliefs and democracy. There<br />

is no doubt that British people voted for Brexit<br />

and if one believes in democracy, then one has<br />

the obligation to introduce Brexit. That is where<br />

I end up coming from, but I believe profoundly<br />

in democracy. The question is when to give<br />

people a choice, but if you do give them one,<br />

then you have to go with that. There are many<br />

different versions of this, though. One would be<br />

of a United Kingdom that is inward-looking and<br />

small-minded, and there is one where Britain<br />

comes through as a country with the same<br />

character, outward-looking, international, and<br />

embracing the world. For me the key task is to<br />

make sure that Britain is this outward-looking,<br />

international country that it traditionally has<br />

been. This is the biggest task for all of us who<br />

are British here in the UK. For me, this is one of<br />

the great attractions of coming to Wolfson, as it<br />

seems to be a very good place to make sure that<br />

we stay highly open and international.<br />

To stay on the topic of Brexit, it seems to be about<br />

a conservative vote rather than the testimony<br />

of an outwards-looking view of the world. It<br />

was more like a step back from an international<br />

Britain towards one that wants to be more<br />

inward-looking.<br />

I am not sure I agree; we don’t have the data.<br />

There are loud voices that argue for the smallminded<br />

Britain, but I know many people who<br />

voted Brexit because they wanted more freedom<br />

and disliked bureaucracy, and others who didn’t<br />

8 9

elieve the European Union represented a<br />

successful international organisation. To be<br />

honest, I don’t know why most people voted the<br />

way they did. I think there is at least a variety<br />

of opinions and reasons, and that’s why I don’t<br />

think it’s a closed story. This is a story with<br />

two different possible outcomes. And one is an<br />

outward-looking Britain.<br />

I suppose it also depends on the government<br />

that is going to implement Brexit and how the<br />

country is then going to look like. It also probably<br />

has to do with the whole international panorama<br />

of a new kind of populism and nationalism that is<br />

growing in the world, and the pressure this could<br />

put on Britain.<br />

Yes. I think, and I followed European masses now<br />

for thirty years or so, it has always gone through<br />

various phases. Sometimes the European Union<br />

economically is doing rather badly, and in those<br />

cases Britain tends to be rather Euro-sceptic.<br />

And then, when the European Union’s economy<br />

is doing rather well, Britain has become more<br />

pro-European Union. And at the moment the<br />

European economy is on an upswing, and if one<br />

would ask British people: “Would you prefer to<br />

be a German economy, a French economy or<br />

a British economy?” people would tend to be<br />

seeing the European economies as something<br />

to admire. I think that will impact people’s<br />

attitudes.<br />

There was something interesting about Brexit,<br />

about how that in the big cities and the cities<br />

with big universities people voted to remain, and<br />

it was the rural areas, where education is, let’s<br />

say, not as advanced or as available as in the big<br />

cities, where people voted for Brexit. So, again,<br />

this is connected to my point on the inwardness<br />

and outwardness of Britain...<br />

But I think this is where you need to be really<br />

careful about elitism, because that sort of<br />

approach does suggest that the better educated,<br />

the richer, the city-livers are right, and that<br />

they really ought to be in charge and make the<br />

decisions, and that the rest, the poorer, less welloff,<br />

rural people – they don’t know what they<br />

are talking about. That is why I’ve mentioned<br />

the crisis of democracy, because if you believe in<br />

democracy, you have to be really worried about<br />

that kind of division. And what that needs to<br />

impel you to do is address the interests of the<br />

less well-off in our society or the less welleducated.<br />

And so I fear that a number of people<br />

who are remainers have become angry with the<br />

majority, when we ought to be thinking about<br />

how do we change the nature of our society, so<br />

that the interests of all are reflected in the way<br />

we make policy.<br />

It is probably fair to say that remainers and<br />

urban elites have probably had it pretty good<br />

for most of the last fifty years, because they’ve<br />

had all the privileges, the politics have gone<br />

their way, and they’ve been able to describe<br />

some of the feelings, that others have, as not<br />

politically acceptable, whereas everyone’s<br />

opinion in our society is acceptable. We need to<br />

listen to those who contradict us. That’s why I<br />

think – returning to my earlier point – the need<br />

to create safe spaces, where you can hear what<br />

everyone is saying, becomes so important.<br />

Is there a border you would like to erase – taking<br />

into account your professional experience?<br />

To raise or erase?<br />

To erase. But raising would also be an interesting<br />

question!<br />

Well, there is a very good quote by a friend<br />

of mine, in which he says that there is no<br />

international situation to which the right<br />

answer is to build a wall. So I don’t think there<br />

is a border I would want to raise anywhere. Now<br />

on to the ones I would love to get rid of… In<br />

my experience with the border between India<br />

and Pakistan, it would be wonderful if that<br />

border could become a much more open one,<br />

but that clearly relies on those two countries<br />

finding a better mode of communicating and<br />

understanding each other.<br />

As I professionally spend a lot of time working<br />

with Madrid, Gibraltar and the UK on their<br />

relationship, I would love it if in the context of<br />

that border, that frontier, we could find a way in<br />

which the three parties involved there could just<br />

live with a frictionless border, or a frictionless<br />

frontier. But we haven’t gotten there yet.<br />

Lisa Heida, ‘Sammy’.<br />

10 11

Nicholas Pierpan, ‘THE SWELLS’.<br />

There are houses even<br />

now without a road, re-enclosed<br />

by birch and maple.<br />

They tempt us out on Sunday<br />

past the far county<br />

bends: a place to drink<br />

in peace, see walls surface<br />

within the oaks and brown ash.<br />

A cry and we stop the Ford,<br />

crawl out one by one<br />

through summer undergrowth,<br />

like savages gaining on<br />

some lost and wounded beast,<br />

last looks decide who goes<br />

in first – makes sure we’ve found<br />

the swells of an empty house<br />

abandoned to the forest,<br />

still sheltering dead<br />

furniture, insides<br />

misshapen by dust and<br />

the shit of infinite mice.<br />

We smash every<br />

window in the place<br />

and drink a toast.<br />

*<br />

Years later – Somerset,<br />

England. No longer turning<br />

vagrant corners.<br />

I met you here, but<br />

distance remains that<br />

neither will ferry.<br />

Visiting your kindly parents<br />

we take a walk through nearby<br />

woods, say little until a field<br />

breaks up the trees: livestock’s<br />

summer-refuge. Cattle graze<br />

this shaded pastureland<br />

and then a house appears –<br />

farmer-like, familial,<br />

but no road in any direction.<br />

There is only the field, the trees,<br />

that house, now mirrored in your eyes.<br />

Tell me who lives in that place.<br />

YASSER KHAN: ‘NOTHING IS HARDER ON THE SOUL,<br />

THAN THE SMELL OF DREAMS, WHILE THEY ARE<br />

EVAPORATING.’ - MAHMOUD DARWISH<br />

(pen on paper).<br />

(The title of Yasser Khan’s sketches are verses from poems written by the<br />

Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Their focus is the impact of borders on<br />

the psychology of those who suffer. The face, the eyes, the atmosphere are all<br />

expressive of the turmoil which manifests itself in a complexity of emotions<br />

much beyond the capacity of language.)<br />

12 13

I recently had a conversation with my parents,<br />

who were visiting me here in Oxford from<br />

Hungary. Although they have visited me many<br />

times already and we used to travel a lot together<br />

when I was a child, they still feel the urge to<br />

mention how easy it is just to take a plane and<br />

cross one border after another. It got me thinking<br />

how mobility of individuals was different before<br />

I was born. Of course, I heard many stories<br />

from my parents, having come from Hungary,<br />

an ex-socialist country. The following article<br />

was created from a long chat, or interview if<br />

Emese Végh<br />

“CROSSING BORDERS IN HUNGARY<br />

DURING THE COMMUNIST ERA”<br />

you like, with my parents about their personal<br />

experiences with borders. They were born at the<br />

end of the 1950s, so they experienced the worst<br />

restrictions, the moderately bad, and winds of<br />

change in the 1990s.<br />

Hungary was a satellite state under the<br />

political control of the Soviet Union from 1949-<br />

1989. There were three large waves of emigration<br />

from the country: in the 1930s many people left,<br />

after 1945 most of the aristocrats fled the country,<br />

and then the final wave in 1956. The latter wave<br />

was due to the fall of the 1956 nationwide<br />

revolution against the communist-government,<br />

when many people left the country and fled to<br />

West (i.e. non-communist countries), mostly to<br />

the United States and Canada. Because of this<br />

wave of emigration, the government declared<br />

all those who wanted to travel towards the West<br />

“suspicious”, and assumed nobody would want<br />

to return once they left the country. During the<br />

1960s nobody could cross the Hungarian border<br />

towards the West, except athletes competing<br />

in international competitions, artists, and<br />

researchers.<br />

Travelling from Hungary in the<br />

1970s<br />

From the end of the 1970s citizens could<br />

acquire a passport and had the right to travel<br />

to foreign countries with permits given by the<br />

police. If you received this permit they stamped<br />

your passport at the police station. Whether you<br />

received this permit or not was completely up to<br />

the mood of the policeman. If people wanted to<br />

make sure they received a permit they had to<br />

find a contact, a man on the inside, working at<br />

the police station and let them know they were<br />

coming, which demonstrates the corruption of<br />

the system. People could go once every three<br />

years to non-socialist countries and once a year<br />

to countries in the Eastern Bloc. However,<br />

they could only carry money up to the value<br />

of $50 per person. This amount of cash would<br />

have only been enough for two days, so people<br />

exchanged as much money as possible and<br />

hid it wherever they could. Common hiding<br />

places included cigarette boxes, underwear,<br />

and even inside baked cakes. My mother, for<br />

example, went for a three-week trip to Split in<br />

today’s Croatia (former Yugoslavia) after her<br />

graduation. In order to have enough money<br />

for her holiday, she extracted the tobacco from<br />

the tube of the cigarettes and rolled 10 Dinar<br />

notes (the currency of former Yugoslavia) into<br />

each cigarette. Although if caught she would<br />

have been incarcerated, everyone knew people<br />

had more money with them than allowed.<br />

When people wanted to ensure they would<br />

not get caught, they put a $100 note into their<br />

passports for the border force officer. The bribe<br />

ensured that the border control would not open<br />

the cars or check people’s clothes and personal<br />

belongings. The border control was more relaxed<br />

when entering Austria because they were a<br />

capitalist country. When visiting other socialist<br />

countries people had to experience the same<br />

terror twice: once when entering the country<br />

and again on their return. People who worked<br />

in high-ranking jobs for the police forces could<br />

not leave the country even for holidays, because<br />

the government was afraid they would act as<br />

spies and because they could easily stay in the<br />

West. Since a large part of the population had<br />

relatives in Western countries, their families<br />

could ensure that they pay for Hungarians’<br />

travels and holidays. If those relatives left in<br />

1956, they were discriminated against and were<br />

not likely to receive a permit for the visit. Those<br />

outside of the country could not visit their<br />

families until the mid-1980s.<br />

Many Hungarians had German origins. If<br />

they could prove this, they only had to receive a<br />

permit for a holiday to West Germany and then<br />

Germany would grant them citizenship and<br />

they could settle down there. Other capitalist<br />

countries gave political asylum in special<br />

circumstances. My maternal grandfather was<br />

able to prove abuse from the socialist government<br />

of Hungary and received political asylum. The<br />

government repeatedly nationalised his family’s<br />

large properties and businesses leaving him and<br />

his family destitute. He fled Hungary while<br />

pretending to take part in an organised trip to<br />

Vienna for the blind and badly sighted.<br />

Although annual visits to a country in the<br />

Eastern Bloc were allowed, you could still only<br />

take $50 worth of currency with you. People<br />

mostly went to Yugoslavia, to the Adriatic Sea,<br />

or to East Germany because of their cheap<br />

alcohol. The lucky few that lived in a 20 km<br />

range of the Yugoslavian border could acquire<br />

a “short border-crossing passport” with which<br />

people could visit neighbouring towns in<br />

Yugoslavia eight times a year. The only big city<br />

in this range in Hungary was Szeged, where my<br />

father went to high school and university.<br />

14 15

Travelling from the West to<br />

Hungary<br />

Hungary did not have foreign currency<br />

income from goods, since it was forbidden to<br />

sell anything to the capitalist West. However,<br />

tourism from West Germany and Austria<br />

formed a large part of the economy. Many<br />

German families came to Hungary to reunite<br />

for a holiday after their countries were torn<br />

into a West and East side. For example, Angela<br />

Merkel, the current German chancellor, who<br />

grew up in East Germany came to Hungary<br />

many times to reunite with her relatives from<br />

West Germany. When tourists from the West<br />

came to Hungary for more than thirty days,<br />

they had to announce their stay at the local<br />

police station.<br />

Both of my parents had relatives in<br />

Western countries - from my father’s side, in<br />

England, and from my mother’s side, in Canada.<br />

My Canadian relative emigrated in 1956, so<br />

she could not visit her family in Hungary until<br />

the mid-1980s. She sent many presents to my<br />

mum’s family, but duty control intercepted and<br />

stole everything that looked valuable. After the<br />

repeated stealing of goods, she put the clothes<br />

into muddy water so that the duty control<br />

would not confiscate them. Her family could<br />

later clean them and sell them at the market for<br />

extra cash.<br />

Travelling from the East to<br />

Hungary<br />

Due to the “relaxed” atmosphere, the many<br />

thermal baths, and because of Balaton, the<br />

largest warm water lake of Central Europe,<br />

Hungary was an attractive destination for<br />

tourists from other communist countries.<br />

Hungary had a special position during the<br />

communist era and was called, “the happiest<br />

barrack”. Socialism was much more relaxed<br />

and “westernised” in Hungary than in any<br />

other communist country. János Kádár, the<br />

communist Hungarian leader, fought for these<br />

rights and special treatment in Hungary, and<br />

so the relationship with the other communist<br />

leaders was tense. Hungarians could travel, and<br />

some small businesses could exist, which was<br />

unimaginable in other communist countries.<br />

People from other countries could not travel to<br />

the West at all or with much larger restrictions:<br />

only researchers and athletes could travel with<br />

special permits, even in the 1970s and 1980s.<br />

Bulgaria, Romania, and East Germany must<br />

have been the hardest to live in as they were the<br />

most restricted, and experienced the harshest<br />

communism. When East Germans came to<br />

Hungary to meet their families they even risked<br />

not being able to get back to their country.<br />

In Conclusion<br />

My parents left me in shock when<br />

describing the way of life and the restrictions on<br />

the freedom of movement they grew up with. It<br />

is easy to forget how convenient travel is for us<br />

millennials, especially in the European Union.<br />

Borders in Schengen countries do not exist:<br />

you don’t need to stop or have ID when driving<br />

from today’s Hungary to another Schengen<br />

country, which was unimaginable in my parents’<br />

youth. After they noticed how sorry I felt for<br />

them and their past experiences they said it<br />

was the norm for them, and that they did not<br />

experience it that badly since they were young.<br />

Even if they had been allowed to travel more<br />

than once every three years to the West, they<br />

needed those three years to collect the money<br />

needed for a long family holiday in France or<br />

Italy. They grew up with dual consciousness;<br />

they were told completely different things in<br />

school and at university than at home. They had<br />

to listen to the ideological nonsense imparted<br />

by institutions but forget it right away. Not<br />

even the teachers believed what they said or<br />

taught, but they were told what they had to say.<br />

Although both of my parents are from a welleducated<br />

background, they believe even the<br />

worker-peasants would have not believed the<br />

communists.<br />

Lorenzo Petralia, ‘See you on the other side’<br />

16 17

YASSER KAHN, ‘AND I TELL MYSELF,<br />

A MOON WILL RISE FROM MY DARKNESS’<br />

- MAHMOUD DARWISH<br />

(charcoal on canvas)<br />

GOSSIP<br />

To cross it and step<br />

Into the place where they gossip.<br />

To become the curtain which waves<br />

Without wind<br />

And wish all friends as weightless:<br />

I will be aware<br />

Of why you want me ghost<br />

Only sixty years or so<br />

Later.<br />

For now, I hold their whispers,<br />

Senseless in the syntax of disappearance<br />

—The stuff that stays on confessionaries’<br />

wooden walls,<br />

Lingering as God’s words<br />

For the kneeled ones.<br />

But I know it’s you,<br />

Trying to remember, tooth by tooth,<br />

How having a mouth in the middle of<br />

the face tastes like,<br />

And failing to express<br />

The causes which lead you<br />

To this lipless existence.<br />

It’s them,<br />

Arranging the pieces of the puzzle<br />

By colour<br />

So I can solve it swiftly,<br />

When I finally learn the stammers<br />

They use as language:<br />

Like the art of tai chi,<br />

A life-long learning.<br />

Untold kisses, drunk, behind doors on<br />

Christmas dinners,<br />

A silence from granny, days after being<br />

diagnosed with dementia,<br />

The motives for your becoming all creaking<br />

on wooden floors<br />

On an almost written goodbye letter,<br />

All disclosed with the parlance<br />

Of gossamer:<br />

Sinful will be the secrets<br />

Kept beyond this border.<br />

Eduardo Paredes Ocampo, “TWO POEMS”<br />

WHITE SHARK’S<br />

WET DREAM<br />

A body-size tattoo<br />

Of the horizon.<br />

If asked about the story behind it,<br />

As we sometimes do with strangers at parties,<br />

He would talk of the Pacific’s sleepless nights,<br />

Restlessly roaming the coasts of Sayulita for a fix<br />

And waking up the next morning<br />

Still tasting the flesh of the virgin<br />

Who, drunk,<br />

skinny-dipped<br />

In the ocean at dawn.<br />

A border, drafting<br />

The cancellation of the vertical pulls<br />

That keep us, between bliss and abyss, floating:<br />

A scrawl, from head to tail,<br />

Which paints him<br />

In two colours:<br />

From below,<br />

The white of Archangel Gabriel’s feathers,<br />

From above,<br />

The gray of Beelzebub’s scales.<br />

But inside such a small crystal cage<br />

—the aquarium, the world, the poem—<br />

Such great creature’s prison tattoos<br />

Looked tuned down:<br />

The arms of the full-face swastika<br />

Metamorphosed into a lucky four-leaf clover.<br />

But he<br />

Still dreams of himself ink-free:<br />

A borderless flesh<br />

With no traces of his double, the albino.<br />

A dream of endless low waters,<br />

And the promise<br />

Of a fresh pair of legs<br />

With every turning of the tide.<br />

18 19

my boarding pass and my completed entry form. Both were still in there. It’s all there, I told myself.<br />

It’s all streamlined...<br />

10 minutes. Tick tock.<br />

My stomach sank lower and lower. I recalled my first ever flight experience and the number of paper<br />

bags I went through at landing. Years have gone past and the feeling of nausea has waned, but it still<br />

wasn’t comfortable. Focus. Don’t forget the mission. I need to focus.<br />

0 minutes.<br />

‘Zero Hour’<br />

David Yuxin Wang<br />

Landed. Passengers stood up to retrieve their carry-ons from their overhead cabins as the seat belt<br />

sign disengaged. Unbuckled, my duffel held tightly in my lap, I could feel a build-up of cold moisture<br />

in my palms. I restarted my mobile phone and double-checked the clock. It was about time... Ready...<br />

Go! Reset. 15 minutes. Tick tock!<br />

Heathrow is overwhelming, and 15 minutes is just an arbitrary number - sufficiently short to be<br />

physically possible and to get the job done. As swiftly and naturally as I could, I navigated past<br />

unsuspecting travellers moving at their own leisurely pace. Speed was what I needed, but there<br />

certainly was no need to make a scene. Passport - check. Wallet - check. Mobile phone - check. I was<br />

only meters away. Meters.<br />

1 minute. Tick tock.<br />

The seatbelt sign above my head lit up and instantly, a dose of adrenaline wriggled through my tiresome<br />

form.<br />

47 minutes. Tick tock.<br />

It took a few seconds for me to clear my head. Cautiously, I peered over my neighbour, who was still<br />

sound asleep, and glanced through the window. Clusters of bright lights dotted across the darkness<br />

of night, tracing each and every human activity within metropolitan London. Whilst inspecting my<br />

watch, I suddenly noticed I was still eight hours ahead. Damn, I should have turned the clock back<br />

earlier. Carefully, I corrected the time to GMT and took a deep breath.<br />

38 minutes. Tick tock.<br />

This isn’t the first time, I reminded myself. All I needed from this moment onwards was a sharp mind.<br />

This should be nothing new, but I could feel my nerves creeping up. Amidst bouts of attempts to slow<br />

my breathing and heart rate, I began to map out the plan. There is nothing difficult. Everything is<br />

under control. Everything will be okay.<br />

23 minutes. Tick tock.<br />

Everything had been packed and organised in the right places. Habitually, I slipped my hand into<br />

my inner jacket pocket and fumbled my passport. Having obtained my first passport at age six, this<br />

was my third issue. The adrenaline overdrive unwound slightly when my fingers sensed that familiar,<br />

rough texture of my passport cover. Slotted between its cover and my ID page, I traced the edges of<br />

Bad news. People. Lines of people. There must have been a couple of other flights landing at around<br />

the same time. Two, four, six, eight, ten... Too many people. Impatiently, I stood in line. This wasn’t part<br />

of the plan. Streamlined, remember? I needed a Plan B.<br />

Minus 46 minutes. Teeeee-k tooooo-k.<br />

45 minutes have passed. Waves and waves of travellers waving British and EU passports have glided<br />

past as I moved a total of six spaces down the line. Two, four, six... Never mind. What was the point<br />

of counting? I should have known this was mission impossible. Why did I place hope onto something<br />

that would only promise disappointment?<br />

There was never going to be a Plan B.<br />

As I glanced across at the two poker-faced UKBA officers sitting under a glaring sign that read ‘All<br />

Passports’, scrutinising and questioning each and every international traveller ahead of me, I let out<br />

a long sigh of defeat. The plan didn’t matter; nor did its execution. I was never going to be any faster<br />

than what the bureaucratic system demanded me to be. Stuck at the border, I, a foreigner, finally let<br />

down my guard and allowed my mind to drift.<br />

Minus 65 minutes. Tick tock.<br />

It was Saturday night. If I made it back before 2 am, a couple of beers in the Wolfson bar would make<br />

my life a bit better. If and only if.<br />

Tick tock…<br />

20 21

ALESSANDRO VATRI, ‘THE WALL’. Taken in Nicosia (Cyprus), 2015.<br />

A café by the physical border between South Nicosia and ‘no-man’s land’.<br />

Asmi Khushi, ‘Do I Draw Borders Around Myself?’<br />

III.<br />

I.<br />

Do I draw borders around myself<br />

I wipe them off to let you enter<br />

completely because I am a part of you<br />

this being a letter to every lover<br />

And one mother<br />

I am all yours, I don’t quite exist<br />

By myself<br />

My culture is of porous boundaries<br />

says a social psychology text book<br />

So I say my culture is<br />

of cackling laughter when we permit<br />

Others in, of sorrows carried together<br />

our shoulders bowed and join<br />

my caste identity is yours<br />

we’re both powerless, incapable<br />

my gender is yours,<br />

we’re both threatened, vulnerable.<br />

my religion is yours,<br />

we’re both sinners, terrorists.<br />

So I sleep in your arms restlessly<br />

hold you through every storm<br />

we drown together<br />

I taste love raw, naked and unformed<br />

like broken buildings, broken roads<br />

broken bridges,<br />

broken transport.<br />

Why do I draw borders around myself?<br />

Because borders were drawn in the first place,<br />

between the East and the West<br />

between the North and South<br />

between the hungry and the bloated<br />

between the growing and the insane?<br />

Or<br />

because the cell separated<br />

because the dolphin differs from the locust<br />

because snowflakes form in uncountable shapes<br />

because the child combined the genes of his<br />

parents<br />

to become something new;<br />

because everything beautiful and sacred<br />

must be protected to survive?<br />

And do I pick up that charcoal stick,<br />

Or the colours of spring?<br />

II.<br />

Do I draw borders around myself<br />

Now far away in a distant land<br />

in the country of the wind snow and feeble rain<br />

On another face of the globe,<br />

where faces are paler and colours fade away<br />

I walk alone heavy and pregnant<br />

with hungry children from back home<br />

Here people draw borders<br />

nice charcoal lines smooth and edgy<br />

through whipped strokes I can’t get in<br />

Water smudges charcoal lines<br />

Seeping through, leaving traces<br />

the borders run inwards, into building<br />

towers, into arches<br />

The borders smudge into cobbled streets<br />

the borders smudge into universal healthcare<br />

drawn roughly<br />

Borders break in the night,<br />

at the sacred feet of the homeless<br />

they burn and sputter and choke<br />

at the music flowing out of dim pubs<br />

they break down and people break<br />

sometimes they float into borderless domains<br />

for which they unknowingly thirst.<br />

I see them starve and thirst<br />

I can’t serve water<br />

but is it because of the lines?<br />

Or because my wells run dry?<br />

22 23

“LIKE THE HUMAN HEART”<br />

Álex Sartoris<br />

There’s something to be said about the sounds of trains in the distance: they soothe the soul. Or so I<br />

like to think, sometimes. Some other times I don’t even think I have a soul. Still, this is not my story<br />

but rather someone else’s.<br />

It was on one of the first days of fall that I walked to the place I go when I feel sad and want to<br />

be alone. It happens to be an old McDonald’s overlooking the edge of town, as the Springsteen song<br />

goes, and from its terrace you can watch trains departing an even older railway station, far enough so<br />

that they look like a line between the meadows and the sky, and yet so close you can still hear them as<br />

they speed away into the sunset at dusk.<br />

There’s something to be said about McDonald’s, too: no matter where you are in the world or if you<br />

ever get lost, be it a highway in the desert or one of those concrete jungles we call cities, you can always<br />

find solace in between their facsimile walls. God bless globalisation for these small miracles. Perhaps<br />

it is this abatement, to instantly believe I’m somewhere I know and will always know wherever I am,<br />

that draws me to this place again and again. However, as it happens, I find myself ever more oblivious<br />

to my surroundings than to my thoughts. That may be why at first I didn’t see her sitting by a table on<br />

a corner, her face towards the same sunset I had been watching until then.<br />

It took me a while to recognize her because of the years, her sunglasses and her hair – once blond,<br />

it now glowed pink as gum. Nevertheless, there was still an aura of improbable beauty around her, like<br />

snow on a summer day. I stood up and neared her.<br />

‘Claire, is that you?’<br />

She looked at me then, but said nothing.<br />

‘It’s me, Álex. You know, I was friends with your brother at school. May I sit down?’<br />

She shrugged and I took a place, unaware of the fact that I obstructed her view of the sun.<br />

‘It must have been, what? Ten years?’<br />

I really couldn’t tell how fast time had flown since I had last seen her. Before I knew, I was talking<br />

again.<br />

‘You know, I often think of him. Max, I mean. It’s been ages since I last spoke to him. And you. I<br />

sometimes think of you, too.’<br />

Her brother and I had one of those friendships that were everlasting as long as school years lasted,<br />

right until college started and we all drifted apart like castaways after a shipwreck. On summer days<br />

I’d ride my bike to their house. I couldn’t be more than twelve, and mum was always somewhere else,<br />

working. Where my dad was, that’s something she wonders still. When I think of that summer, I<br />

remember the lawn behind their house, the pool we’d jump into, the room where Max and I would<br />

play videogames or jerk off for the first times to Madonna clips on an old computer.<br />

When I think of Claire, I remember long afternoons by the pool, water dripping from her hair, the<br />

blue of her eyes. I also remember we played hide and seek with her brother, careful not to disturb their<br />

father, whom I remember always sitting in front of a TV, beer in hand. Claire and I always hid inside<br />

a closet in her bedroom which proved a perfect cocoon from the outside world. We could see the bed<br />

through the keyhole in the wooden door and hear Max’s footsteps in the corridor before he gave up<br />

on us and went somewhere else to play. We stayed a little longer, and she would hold my hand then<br />

and tell me how she often hid in there.<br />

She produced a smoke from her purse. The moment she lit it made me feel like something precious<br />

had been lost that would never be found again. She took a drag and let the smoke out through her<br />

nose, her eyes still hidden behind the shades. The sky was now the same colour as her hair, which gave<br />

her the somewhat hieratical looks of a sculpture or a ghost.<br />

When I asked Claire why she hid in there, she replied: ‘It’s because of monsters’. I thought she was<br />

old enough not to believe in monsters anymore. Now I wonder if she had ever been young at all. Back<br />

then, I still didn’t know monsters had a human face, a human smile, a human heart. Nightmares made<br />

of flesh and bone lurking in broad daylight.<br />

Her phone chirped and she held it with both hands. I could see the screen reflected on her sunglasses<br />

as she started texting.<br />

‘If you’ll excuse me, I need to go to the toilet’, she said and then she disappeared into the building.<br />

I stood there, still thinking of the last summer I spent at their house. I had biked all the way there<br />

to find that only their father was at home. His breath reeked of beer when he told me Max and Claire<br />

had gone shopping with their mother. He said they’d be coming any time soon, though, and that I<br />

could stay until then if I wanted to. He sat in front of the TV and fell asleep as if I had never shown<br />

up, so I went to Claire’s room and waited there.<br />

She used to draw a lot, I recall now. She was too shy to lend any of her pictures, and so I thought<br />

this could be my chance to take a better look at them. I was scanning through some sketches when<br />

I heard a door shut and a sense of guilt grew inside me. Afraid that she would get mad at me for<br />

being in her room without her knowing, I did the only thing that seemed reasonable at the moment:<br />

I opened the closet door, slipped inside and closed it behind me. Not a minute later, Claire walked in<br />

the room. I should have opened the door right then and explained why I was there, but I didn’t. Things<br />

might have followed a different path then. Instead I remained silent, careful not to give myself away.<br />

I wanted to see; what, I did not know then, nor could I have imagined.<br />

She pulled over her t-shirt and threw it to the floor. An ethereal steam of sweat rose from her skin,<br />

and I could see the ever more protruding shape of her breasts beneath a white bra. She unbuttoned her<br />

trousers and let them fall to the floor. From where I was, I could see the first signs of pubic hair were<br />

starting to sprout here and there on the leg openings and band of her panties. And then it struck me<br />

that she was going to open the closet looking for something to put on. Still, I could not take my eye<br />

off the keyhole. Then she turned around, and even though I could not see past her, I somehow knew<br />

her father was there, too. It smelled of beer.<br />

I never told anyone what I had seen there. For years it haunted me like a bad dream. As I grew up<br />

I sometimes found it exciting, only to feel empty afterwards and hate myself for it. In time, it became<br />

less a memory than a nightmare, or at least I wanted to think it had been nothing more than that. And<br />

though it still lingered somewhere in my mind, I came to doubt its veracity. I had to.<br />

When it happened, I was too scared or confused or simply too astonished to do anything. All the<br />

while, Claire looked toward the closet and her eyes were an infinite blue that could almost pierce<br />

through the door. Bent as she was on the bed, one of her hands was gripping the bed sheets while the<br />

other was reaching out towards me for something that wasn’t there, and then I, too, held my hand<br />

towards the door, as if trying to hold hers.<br />

Like that day, I then stretched an arm towards the emptiness she had left before me. I wanted to<br />

hold her hand and tell her how sorry I was, but there are invisible walls we cannot cross, and I could<br />

never reach out for her any more than I can reach out for you. Besides, I was and would always be late,<br />

ten years too late.<br />

By then the sky had bruised to night already and the last train had long departed the station. When<br />

it was clear she wasn’t coming back, I stood up and walked away.<br />

24 25

V.<br />

Cristina Blanco Sío-López, ‘THE WARPING OF WINDS’<br />

Slow,<br />

swimming in factors<br />

A Pedro<br />

I.<br />

Far from<br />

distant precautions,<br />

undeclared wars,<br />

tuning to loopholes,<br />

resonating crystal growing<br />

through my bones.<br />

Touch<br />

the passing river<br />

knowing<br />

when it explodes.<br />

III.<br />

II.<br />

From an embrace of sand<br />

to the whirlpools of fire.<br />

From the cluttered sky,<br />

to the soft hook of light,<br />

a swinging spectrum<br />

so wishing to fly.<br />

And now, where's your sand?<br />

where's your hand?<br />

where's the perfume of hours?<br />

the flaming desire to live and to<br />

fly?<br />

Your hand is a cloud,<br />

your wings are departing,<br />

IV.<br />

A caress of winds,<br />

a kiss of the sun,<br />

plunging in feathers,<br />

singing spheres,<br />

bathing in light,<br />

touching the water,<br />

with the widest<br />

of eyes.<br />

a sight that is seeking,<br />

the calm of the angles,<br />

a fluency of mirrors,<br />

a stroke of moonlight.<br />

Your tongue and your fingers<br />

depicting new canyons,<br />

a whisper of rivers,<br />

deluded in reasons,<br />

delighted<br />

to come.<br />

Your shadow was right:<br />

the one that you abandoned,<br />

the star on the coastline,<br />

the glimmering fragment<br />

was the key to the velvet,<br />

the whisper in secret,<br />

the water<br />

in your hands.<br />

Now,<br />

lost<br />

in the voiceless realms<br />

of games without traces,<br />

of forbidden ferments<br />

of purple and rye.<br />

But shoulders are waiting<br />

for circular dances,<br />

for pungent eclipses,<br />

for wishes amounting<br />

a swift invitation:<br />

a change of the tides.<br />

That's the step:<br />

the void is embracing<br />

a warmth that's arising,<br />

a hand is extended,<br />

it's the day of rotations,<br />

the fall of all gravity<br />

a zenith of voices,<br />

the moment of meeting,<br />

the will of the rhythms,<br />

the echo of the skin,<br />

your scent is the shadow of a<br />

blossoming spine.<br />

the open reflection,<br />

the warping of winds.<br />

26 27

Merryn Williams, ‘ON THE TOWPATH’<br />

Canals are where you head. The roving cameras,<br />

ubiquitous, can’t reach you. As I walk<br />

I hear slight sounds, from people asleep in barges.<br />

They are in no danger.<br />

I left at first dark, when the radio told me<br />

they’d crossed the border, killing as they go;<br />

packed water bottle, biscuits and my compass,<br />

and now it’s thick dark, and they’re on my trail.<br />

I trashed my papers, left my aging parents,<br />

only the strong are fit for the long trek;<br />

a few rushed words, just time to fake a story.<br />

It’s on my conscience, but they told me: Go.<br />

Yasser Khan,”A PERSON CAN ONLY BE BORN<br />

IN ONE PLACE. HOWEVER HE MAY DIE SEVERAL TIMES<br />

ELSEWHERE: IN THE EXILES AND PRISONS, AND IN<br />

A HOMELAND TRANSFORMED BY THE OCCUPATION<br />

AND OPPRESSION INTO A NIGHTMARE.”<br />

- MAHMOUD DARWISH<br />

(Charcoal on paper)<br />

Bad smells rise up, the flapping of a heron;<br />

night still, can’t tell the white thread from the black;<br />

put foot in front of foot, none walk towards me.<br />

And when light breaks? No choice but to walk on.<br />

28 29

Lisa Heida, editor of <strong>Romulus</strong>, in conversation with Sabira Yameen,<br />

an energetic, inspiring and powerful woman who happens to be deaf.<br />

“What deaf people can’t do? They can’t hear. That is all.”<br />

“IT’S LIKE<br />

I AM BEING PUNISHED<br />

FOR JUST BEING DEAF”<br />

Sabira was born in Bangladesh but now is a resident of the UK. She was a Research Scientist at the<br />

University of Oxford at the Oncology department for three years, 2009 – 2012. With only two hours of<br />

British Sign Language support a week, she felt left out. When her father died, she had a body breakdown<br />

for 7 months, suffering from extreme vertigo. She couldn’t work because of the vertigo. When she got<br />

better, she decided to put herself at top priority, and focused on her happiness. She decided to stop working<br />

at the University of Oxford – also because they test on animals, something she could not reconcile with her<br />

beliefs, being vegan. Currently she is working on self-employment, hoping to establish a cat hotel. Her<br />

passion is justice for all, and the Oxford Vegan Action group, which she set up.<br />

You visited Bangladesh for five weeks not so long<br />

ago. Bangladesh has territorial problems with<br />

India. Have you in any way experienced this<br />

during your last visit? How did you feel about it?<br />

No, I personally didn’t experience any problems,<br />

so I can’t comment on it. However, online visa<br />

application for a visit to India is available for<br />

British Citizens, which I did apply for and it<br />

was a very quick application process, but this<br />

is not the case for Bangladesh Citizens, as my<br />

brother is. He has to go through an interview to<br />

obtain a visa, which took a while; it’s clear that<br />

India has a different attitude towards British<br />

Citizens and Bangladeshi Citizens, despite<br />

being neighbor countries.<br />

Since last August, more than 668,000 Rohingya<br />

refugees have fled from Myanmar for camps<br />

over the Bangladesh border. Myanmar’s actions<br />

are labelled by the United Nations as “ethnic<br />

cleansing” and said it cannot rule out considering<br />

it as an act of genocide. What do you think of this<br />

situation?<br />

I think this is a very sad situation. I was at Cox’<br />

Bazar where many refugees are, but I didn’t go to<br />

the refugees’ camp. However, I saw many of UN<br />

vans at the hotels, where UN staffs are staying.<br />

I believe it was a genocide act committed by<br />

Myanmar from watching interviews given<br />

by the survivors, where people get killed and<br />

driven out for no reason other than they are of<br />

different ethnic and religion.<br />

The camp of the Rohingya refugees is set up on the<br />

narrow strip of land just beyond the Myanmar<br />

border fence. The area is formally still within the<br />

country’s territory, but it is widely referred to as<br />

“no man’s land”. The governments of Bangladesh<br />

and Myanmar say they plan to repatriate<br />

hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees<br />

within two years, a timeframe humanitarian<br />

actors warn is too fast for a safe and voluntary<br />

return. How do you feel about this?<br />

As long as it is not in Myanmar country but in<br />

Bangladesh, I see no reason why there will be<br />

further attack, even though it is considered as<br />

“no man’s land”. The border right next to the<br />

land should be guarded at all times to prevent<br />

any possible further attack.<br />

According to various articles, deafness is a major<br />

public health problem in Bangladesh. “The country<br />

has a population of over 130 million, and about 13<br />

million people are suffering from variable degrees<br />

of hearing loss of which 3 million are suffering<br />

from severe to profound hearing loss leading to<br />

disability.”<br />

The article I cited uses words like suffering,<br />

leading to disability, public health problem, etc.<br />

How do you feel about the negative discourse these<br />

academics (presumably hearing academics) use to<br />

describe being deaf ?<br />

Deafness is only a problem if society doesn’t<br />

provide equal access for deaf people. Deaf<br />

children have the full capacity to learn at equal<br />

measure as hearing children can, but it can<br />

only be done with equal access to education<br />

and opportunity. All the negative words are<br />

incorrectly placed on deafness, all the negative<br />

should be placed at the lack of access and lack<br />

of opportunities. I experienced it first-hand; I<br />

used to go to deaf school from age of 3 and half<br />

to 6 years old in Bangladesh, and the school was<br />

poorly organised, and I wasn’t learning much,<br />

so my parents pulled me out of the school and<br />

put me in a hearing school which was much<br />

better organised, however I was left out by<br />

other hearing children due to communication<br />

issue. At the end, my parents decided that we<br />

needed to move to the UK for better education.<br />

I went to a deaf school in the UK, and I thrived<br />

better. However, it was an oral school, so there<br />

wasn’t any sign language involved, which is<br />

such a shame. My parents later on admitted<br />

that it was mistake that we didn’t learn sign<br />

language since I was diagnosed with deafness,<br />

but such information was not easily available<br />

in Bangladesh, also sign language back in<br />

old time in 1980s and 1990s was severely<br />

discouraged, because it was believed that<br />

learning sign language will hinder integration<br />

of deaf people among hearing society as no one<br />

knows sign language, and there was no sign<br />

language interpreter available in Bangladesh, so<br />

everything was geared toward oral and speech<br />

ability in deaf children.<br />

30 31

Now that you live in the UK, do you feel like there<br />

is a difference between how people act around<br />

you? Would you say the UK is more accepting of<br />

deaf people than Bangladesh, or is it the other<br />

way around?<br />

In Bangladesh, people tend to underestimate<br />

deaf people more, unlike in the UK. Not<br />

surprising, as there is no proper access or support<br />

for deaf people to education, they often fall<br />

behind in classes and have lower achievement.<br />

This is really sad, because I do know that deaf<br />

people can do anything, as long as society and<br />

family allows them to, by providing the access<br />

and support, but if they receive none of those,<br />

it is much harder to progress. We have to<br />

remember that most deaf children are born to<br />

a hearing family: often they never have met a<br />

deaf person before until their own deaf child<br />

came along, and sadly the usual narrative is that<br />

they don’t provide enough support to the child.<br />

It does happen in UK as well to lesser extent<br />

unless the child has very loving and supportive<br />

family.<br />

I have such supportive family who gave<br />

everything to ensure that I get equal opportunity<br />

in education, that is how I managed to have a<br />

Bachelor and Master degrees and I used to work<br />

in University of Oxford as a Research Scientist<br />

on oncology for 3 years, and my research work<br />

(co-authored) was published in 5 journals.<br />

In Bangladesh, government and general public<br />

don’t take much notice of deaf people, they don’t<br />

provide subtitles on TV, and they don’t provide<br />

interpreters, it’s as if we don’t exist. It was same<br />

story in UK many decades back, but I am sure<br />

things will change in Bangladesh in the future.<br />

Having said this, the UK may be much better<br />

than Bangladesh, but still has a long way to go.<br />

In the UK, many of cinemas are not subtitled,<br />

they usually screen a certain movie with subtitles<br />

just once a week at an inconvenient time. If<br />

it’s advertised that there will be subtitles, too<br />

often deaf people arrive and find that there<br />

are no subtitles. Many of services including<br />

government’s branch offices don’t offer BSL<br />

interpreters, even at request, and would say that<br />

if I want BSL interpretation, I would need to<br />

book it myself, and pay for it myself, which is<br />

unbelievable, it’s like I am being punished for<br />

just being deaf. Many times when I need to<br />

make an appointment, it only offers phone<br />

number for me to call, which I am unable to call.<br />

I believe that the government should put more<br />

money aside for equal access for deaf people,<br />

and provide BSL interpreters, and increase the<br />

number of BSL interpreters by encouraging<br />

people to learn BSL by making the courses<br />

much cheaper, and also introduce BSL courses<br />

in schools as part of curriculum, like they do<br />

with French and German languages already.<br />

Also to provide online chats with staff on<br />

website as an alternative for deaf people instead<br />

of just a phone number which deaf people can’t<br />

use.<br />

BSL is even more of importance as it is a<br />

language belonging to our own country instead<br />

of a foreign country’s language, considering the<br />

fact that there are 125,000 deaf adults in the<br />

UK who use BSL, plus an estimated 20,000<br />

children, and 9 million of people in UK face<br />

hearing loss, which is 1 in 7.<br />

Were you born deaf ? Do you remember the moment<br />

you first realized you were deaf ?<br />

I wasn’t born deaf. I was born 2 months premature<br />

and acquired life threatening lungs infection as<br />

my immunity system was not fully developed,<br />

doctors gave me antibiotic drug which saved my<br />

life, but the medicine caused profound deafness.<br />

My family didn’t realise that I was profoundly<br />

deaf till I was nearly 2 years old, because I wasn’t<br />

responding to the noise behind me, and I spoke<br />

very few words. Originally, they thought it was<br />

just normal delay. I particularly didn’t take much<br />

notice of it, until I was fitted with hearing aids<br />

device! I struggled to understand what others<br />

were saying to each other, especially among<br />

my cousins, who were my playmates, I felt bit<br />

isolated, that is the moment when I realised<br />

that I am different from others.<br />

How did you feel about being deaf ?<br />

So many times that there was no access, no<br />

subtitles at cinema, no interpreter at meetings or<br />

at talks, and it is extremely hard in a big group of<br />

people, there is limitation to lip-reading. That<br />

is when I get frustrated, wishing that I wasn’t a<br />

deaf person in first place. The isolation never<br />

feels nice, especially when you just simply want<br />

to know what is going on, and want to make<br />

the connection and give input, but are unable to<br />

do so. It is even more prominent when I am at<br />

the outreach that I myself organise but am left<br />

unable to communicate with public to explain<br />

the purpose of the outreach.<br />

And there are times that I completely forget<br />

that I am deaf, especially when I am with my<br />

immediate family and my partner, because we<br />

all communicate so well because of familiarity.<br />

It is usually a minimum of 3 people, any more<br />

than that becomes a bit of struggle, and in bigger<br />

groups, even more so. It is very dependent on<br />

situations.<br />

Do you feel like your surroundings treat you<br />

different in a negative way? And how do you<br />

think they treat you differently in a positive way?<br />

When I don’t understand what is being said in<br />

groups or if there is speech but there is no BSL<br />

interpreter, and often there are no subtitles on<br />

clips on social media, and so on, when I ask what<br />

they are talking about, I get told “Never mind”,<br />

“Will tell you later” which never happens.<br />

When I am out walking on the street, hearing<br />

people try to get my attention and I explain that<br />

I’m deaf, they will say “Never mind” and then<br />

walk away. This is annoying; they should take<br />

time to explain what they were trying to say and<br />

give me chance to response properly to best of<br />

my ability.<br />

I went on holiday with my friend outside the<br />

UK, and she was meeting a friend of hers, we<br />

all hanged out together for a while. Later I<br />

found out that my friend’s friend remarked to<br />

my friend’s brother that I am beautiful but very<br />

rude and snobby because I kept ignoring his<br />

communication with me, my friend’s brother<br />

laughed and responded “Didn’t you realise that<br />

she is deaf?! She didn’t ignore you on purpose”.<br />

The guy was mortified when he realised his<br />