Part 1: Introduction, first and second language acquisition ...

Part 1: Introduction, first and second language acquisition ...

Part 1: Introduction, first and second language acquisition ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

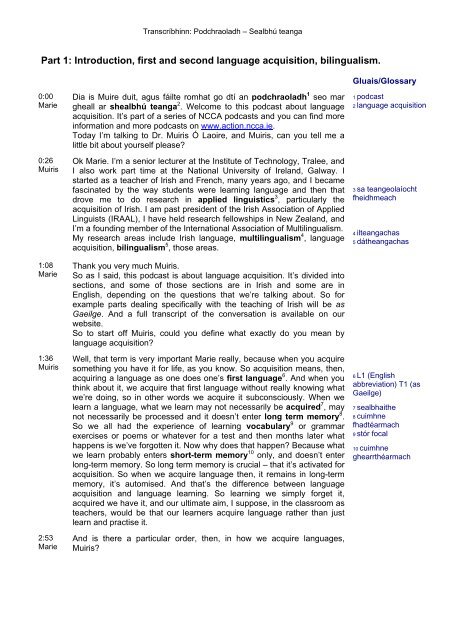

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

<strong>Part</strong> 1: <strong>Introduction</strong>, <strong>first</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>, bilingualism.<br />

0:00 Dia is Muire duit, agus fáilte romhat go dtí an podchraoladh 1 seo mar<br />

Marie gheall ar shealbhú teanga 2 . Welcome to this podcast about <strong>language</strong><br />

<strong>acquisition</strong>. It’s part of a series of NCCA podcasts <strong>and</strong> you can find more<br />

information <strong>and</strong> more podcasts on www.action.ncca.ie.<br />

Today I’m talking to Dr. Muiris Ó Laoire, <strong>and</strong> Muiris, can you tell me a<br />

little bit about yourself please?<br />

0:26 Ok Marie. I’m a senior lecturer at the Institute of Technology, Tralee, <strong>and</strong><br />

Muiris I also work part time at the National University of Irel<strong>and</strong>, Galway. I<br />

started as a teacher of Irish <strong>and</strong> French, many years ago, <strong>and</strong> I became<br />

fascinated by the way students were learning <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> then that<br />

drove me to do research in applied linguistics 3 , particularly the<br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> of Irish. I am past president of the Irish Association of Applied<br />

Linguists (IRAAL), I have held research fellowships in New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

I’m a founding member of the International Association of Multilingualism.<br />

My research areas include Irish <strong>language</strong>, multilingualism 4 , <strong>language</strong><br />

<strong>acquisition</strong>, bilingualism 5 , those areas.<br />

1:08 Thank you very much Muiris.<br />

Marie So as I said, this podcast is about <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>. It’s divided into<br />

sections, <strong>and</strong> some of those sections are in Irish <strong>and</strong> some are in<br />

English, depending on the questions that we’re talking about. So for<br />

example parts dealing specifically with the teaching of Irish will be as<br />

Gaeilge. And a full transcript of the conversation is available on our<br />

website.<br />

So to start off Muiris, could you define what exactly do you mean by<br />

<strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>?<br />

1:36 Well, that term is very important Marie really, because when you acquire<br />

Muiris something you have it for life, as you know. So <strong>acquisition</strong> means, then,<br />

acquiring a <strong>language</strong> as one does one’s <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong> 6 . And when you<br />

think about it, we acquire that <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong> without really knowing what<br />

we’re doing, so in other words we acquire it subconsciously. When we<br />

learn a <strong>language</strong>, what we learn may not necessarily be acquired 7 , may<br />

not necessarily be processed <strong>and</strong> it doesn’t enter long term memory 8 .<br />

So we all had the experience of learning vocabulary 9 or grammar<br />

exercises or poems or whatever for a test <strong>and</strong> then months later what<br />

happens is we’ve forgotten it. Now why does that happen? Because what<br />

we learn probably enters short-term memory 10 only, <strong>and</strong> doesn’t enter<br />

long-term memory. So long term memory is crucial – that it’s activated for<br />

<strong>acquisition</strong>. So when we acquire <strong>language</strong> then, it remains in long-term<br />

memory, it’s automised. And that’s the difference between <strong>language</strong><br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> learning. So learning we simply forget it,<br />

acquired we have it, <strong>and</strong> our ultimate aim, I suppose, in the classroom as<br />

teachers, would be that our learners acquire <strong>language</strong> rather than just<br />

learn <strong>and</strong> practise it.<br />

2:53 And is there a particular order, then, in how we acquire <strong>language</strong>s,<br />

Marie Muiris?<br />

Gluais/Glossary<br />

1 podcast<br />

2 <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong><br />

3 sa teangeolaíocht<br />

fheidhmeach<br />

4 ilteangachas<br />

5 dátheangachas<br />

6 L1 (English<br />

abbreviation) T1 (as<br />

Gaeilge)<br />

7 sealbhaithe<br />

8 cuimhne<br />

fhadtéarmach<br />

9 stór focal<br />

10 cuimhne<br />

ghearrthéarmach

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

2:59 This is a very very interesting question. It’s a question that has exercised<br />

Muiris quite a lot of theorising <strong>and</strong> empirical research over the years. Now to<br />

begin with I’ll talk about learning a <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> 11 . And recent<br />

research has investigated evidence that maybe yes, learners do acquire<br />

in a specific sequence 12 , what they call developmental stages 13 . And<br />

for example, two linguists, Florence <strong>and</strong> Myles, tell us that young learners<br />

of a <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> – English for example – when they’re leaning the<br />

negative 14 , you know, I did not or whatever, they might put the negative<br />

particle either at the beginning or end of a sentence, they’d say:<br />

no me playing here or me playing here no. Then they might go <strong>and</strong> insert<br />

that negative particle in a verb phrase: car not coming<br />

And then finally they manipulate it correctly. So it’s a very interesting<br />

thing then, that there seems to be an order.<br />

Now that’s based on very interesting research that took place in the<br />

1970s by Brown. And he looked at the way that children acquire their <strong>first</strong><br />

<strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> he said, yes, they pass through similar stages, from crying<br />

to cooing to babbling, to just intonation 15 , to one-word utterances 16 , to<br />

two-word utterances to inflection 17 (that means they can change words,<br />

they can add plurals for example) to questions, to negatives <strong>and</strong> then to<br />

complex sentences.<br />

And he looked at children acquiring morphemes (a morpheme 18 is the<br />

smallest meaningful <strong>language</strong> unit. It could be a word, a part of a word,<br />

like dog or even the s, that’s a morpheme too, ‘s’ in dogs). So he found<br />

for example that, in the case of English, <strong>and</strong> in other <strong>language</strong>s there<br />

seems to be this order:<br />

• a present progressive 19 : so you’d have boy singing – ‘ing’ comes<br />

<strong>first</strong>; crying, doing,<br />

• then followed by prepositions 20 : doggy in car<br />

• followed by plural 21 : sweeties<br />

• followed by past irregular: gone<br />

• possessive 22 : [for example baby’s pram]<br />

• past regular comes after that: wanted<br />

• third person singular: eats<br />

• <strong>and</strong> the auxiliary: is running<br />

There has been just one research study that I know of regarding<br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> of Irish as a <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>. It was a study done by McKenna<br />

<strong>and</strong> Wall in 1986 with two young children, Áine <strong>and</strong> Máire. Áine was 18<br />

months <strong>and</strong> Máire was 28 months, in Cnoc Fola in northwest Donegal<br />

Gaeltacht. And they studied what’s called the MLU - Mean Length of<br />

Utterance, or how long their sentences were in terms of time. And they<br />

did look at order. They found that these children began with questions,<br />

<strong>and</strong> then they went to the possessors 23 : the mo (you know–my) <strong>and</strong> they<br />

worked from there to imperatives 24 (giving orders), <strong>and</strong> ended,<br />

interestingly enough, with negatives.<br />

But more <strong>and</strong> more studies need to be done so that we can determine if<br />

that order that you refer to actually takes place in <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong><br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> <strong>and</strong> then if there’s an order in <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>.<br />

And if we know about the order in <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong> (how you<br />

acquire your mother tongue) should we … replicate that order in the way<br />

we present <strong>language</strong> to learners?<br />

11 L2 (abbreviation)<br />

T2 (Irish abbrev)<br />

12 ord, seicheamh<br />

13 céimeanna<br />

forbartha<br />

14 diúltach<br />

15 tuin chainte<br />

16 ráiteas aon‐fhocal<br />

17 infhilleadh<br />

18 morféim<br />

19 an t‐ainm<br />

briathartha<br />

20 réamhfhocal<br />

21 an t‐iolra<br />

22 sealbhach (nó<br />

ginideach)<br />

23 an aidiacht<br />

shealbhach<br />

24 an modh<br />

ordaitheach

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

6:18 And if I’m underst<strong>and</strong>ing you correctly then Muiris, that there’s a<br />

Marie difference between the order in how we acquire our L1 <strong>and</strong> how we<br />

acquire our L2 or other additional <strong>language</strong>s, are there any particular<br />

things that teachers should be aware of or watching out for when we’re<br />

thinking about teaching <strong>second</strong> or additional <strong>language</strong>s?<br />

6:36 Absolutely. I think the thing they must be aware of is what they call<br />

Muiris inter<strong>language</strong> 25 . Inter<strong>language</strong> is a mixture of the <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> the<br />

<strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong>, the mother tongue <strong>and</strong> the <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> that<br />

they’re learning. It’s like they’re meeting <strong>and</strong> the two of them are trying to<br />

co-exist side by side. Inter<strong>language</strong> is not stable – it produces errors.<br />

Young children when they’re hearing <strong>language</strong>, <strong>first</strong> of all they’re looking<br />

for the meaning in their <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>, they’re noticing how things are<br />

different.<br />

Now there can also be transfer 26 . In Irish teachers will know about for<br />

many years the Tá sé fear. This is a transfer from He is a man in English.<br />

And the transfer sometimes can be positive as well, if structures work in<br />

the same way in the <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>: Tá sé mór- he is big <strong>and</strong> that’s a<br />

positive transfer 27 . So, as I said, it causes instability. It can cause as<br />

well what they call fossilisation 28 , <strong>and</strong> actually can stay in the system<br />

forever … somebody could actually go on saying forever Tá sí liathróid.<br />

That would be regarded as fossilisation <strong>and</strong> it can be very difficult if the<br />

<strong>language</strong> is not acquired correctly then.<br />

So inter<strong>language</strong> is very complex, <strong>and</strong> I think it’s good that teachers<br />

realise that if learners make errors it’s actually part of their developmental<br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> <strong>and</strong> they have to go through the stage where sometimes they<br />

make hypotheses 29 about <strong>language</strong> themselves <strong>and</strong> say Well, it must<br />

work in this way. Then they produce something <strong>and</strong> the utterance is<br />

deviant from what’s acceptable <strong>and</strong> that is when error occurs.<br />

But it’s good to think that sometimes: errors – you’re going to meet them,<br />

it’s not necessarily that the teacher has done something incorrectly or<br />

whatever, it’s the nature of <strong>acquisition</strong>.<br />

8:20 When you talk about this developmental order <strong>and</strong> how we have to<br />

Marie accept that children will be making errors, it immediately brings to mind<br />

questions about: well at what stage <strong>and</strong> … the ages of children. Because<br />

when you think about learning Irish as <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> children start at<br />

age four. Is there any research or information about optimal ages 30 for<br />

learning <strong>language</strong>s or anything like that?<br />

8:40 Oh there is, there’s been a lot of work done in that area Marie as well.<br />

Muiris They’ve talked about, that when we acquire <strong>language</strong>s, Chomsky <strong>and</strong><br />

people spoke about this thing called the LAD –the <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong><br />

device 31 … like a biological function 32 which is in the brain, <strong>and</strong> which<br />

is strongly activated when we are acquiring a <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>. Now the<br />

thinking was that that <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong> device, like other biological<br />

functions … works successfully only when it’s stimulated 33 at the right<br />

time. And that made them research this idea of what’s called a critical<br />

period hypothesis 34 – that there’s a specific <strong>and</strong> limited time period for<br />

<strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>. And the thinking is that yes, young children<br />

between four <strong>and</strong> twelve, before puberty, have this – almost – ability to<br />

acquire <strong>language</strong> naturally, <strong>and</strong> later there seems to be a cut-off-point 35 ,<br />

maybe beyond adolescence 36 , although the thinking on this, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

theorising on this, isn’t necessarily fully established.<br />

25 idirtheanga<br />

26 traschur<br />

27 traschur<br />

deimhneach<br />

28 iontaisiú<br />

29 hipitéis<br />

30 aois bharrmhaith,<br />

an aois is fearr<br />

31 mianach<br />

sealbhaithe teanga<br />

32 próiseas<br />

bitheolaíoch<br />

33 spreag (briathar)<br />

34 hipitéis na tréimhse<br />

criticiúla<br />

35 scoithphointe/<br />

pointe scoite<br />

36 ógántacht

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

So yes – there appears to be a cut off point in children’s natural ability to<br />

acquire <strong>language</strong>, <strong>and</strong> yes, early <strong>language</strong> learning appears to be good.<br />

Although, as I said, the jury is out on if there is a cut-off-point at twelve,<br />

thirteen, fourteen.<br />

9:54 That’s very interesting Muiris. Young children acquiring <strong>language</strong><br />

Marie naturally – it automatically brings to mind questions about bilingualism. Is<br />

there anything you’d be able to tell us about that?<br />

10:03 Well, <strong>first</strong> of all, bilingualism is the most natural thing in the world. People<br />

Muiris used to have this fear of bilingualism in the past, in other words if I learn<br />

a <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> will it interfere with my <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>? But when you<br />

look at the world <strong>and</strong> its demography 37 , we remember that if you speak<br />

one <strong>language</strong> – if you are a monolingual – you are actually in a minority.<br />

Research estimates that 60% plus of the world’s population is actually<br />

bilingual or multilingual. And I refer to research done by David Graddol<br />

(1997) back at the end of the nineties on English, <strong>and</strong> he said that about<br />

375 million people speak English as a <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>, but that another<br />

billion use it as an L2. So that shows clearly that most people are<br />

multilingual or bilingual.<br />

Now there are different types of bilingualism, Marie, <strong>and</strong> it might be<br />

useful just to talk about them. There is of course simultaneous or<br />

balanced bilingualism 38 : that’s when you are bilingual from birth, <strong>and</strong><br />

both <strong>language</strong>s develop simultaneously <strong>and</strong> it’s quite balanced. Now a lot<br />

of the bilingualism we are dealing with as teachers is what’s called<br />

additive bilingualism 39 : we’re adding the <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> to the <strong>first</strong><br />

<strong>language</strong>, we’re learning a <strong>language</strong> in school. And then we must be<br />

aware as well of subtractive bilingualism 40 : <strong>and</strong> that means that people<br />

can actually loose their <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong> when they learn their <strong>second</strong><br />

<strong>language</strong> – in the context of immigration 41 . So were I, for example,<br />

Spanish <strong>and</strong> I come to live in Engl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> over the years I may loose, or<br />

use my Spanish less <strong>and</strong> less, so it becomes subtractive.<br />

11:32 That’s a very interesting point when you think about all the children that<br />

Marie are learning English as an additional <strong>language</strong> but already have other<br />

<strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>s.<br />

11:39 Absolutely, <strong>and</strong> maybe we should think of that a little bit more: that they<br />

Muiris are actually bilinguals <strong>and</strong> in fact additive bilingualism is occurring with<br />

English but subtractive bilingualism could be occurring with their <strong>first</strong><br />

<strong>language</strong>.<br />

11:51 And would you say that there are any advantages to being bilingual?<br />

Marie<br />

11:55 Oh, there are indeed. There’s very important research has been<br />

Muiris conducted to show the advantages to being bilingual. There’s research<br />

by Ellen Bialystok carried out in Canada, <strong>and</strong> she’s been working on this<br />

for a long time. She’s been asking Are bilinguals better learners? Her<br />

work has compared cognitive development 42 – particularly in younger<br />

children in the four to eight year age group – <strong>and</strong> she has compared<br />

bilingual children to their monolingual 43 counterparts. And she has<br />

shown consistently <strong>and</strong> clearly that, for example in areas like problemsolving<br />

that includes a little bit of misleading information, bilingual<br />

children perform significantly better.<br />

37 déimeagrafaíocht<br />

38 an dátheangachas<br />

comhuaineach nó<br />

cothrom<br />

39 an dátheangachas<br />

suimitheach/<br />

breiseánach<br />

40 dátheangachas<br />

dealaitheach/<br />

aghdaithe<br />

41 inimirce<br />

42 forbairt chognaíoch<br />

43 aonteangach

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

They are better able to make the distinction between a symbol [the word]<br />

<strong>and</strong> the thing to which it refers [the picture], to underst<strong>and</strong> that words are<br />

only referents 44 . And they can block out any misleading information. And<br />

that holds true for bilingual children not only in pre-reading skills, but also<br />

in tests to do with mathematical concepts, shapes, <strong>and</strong> sizes etc.<br />

12:57 And is that also true for children who are additive bilinguals, children who<br />

Marie have actually learned their <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong>, maybe at school, as well as<br />

people who’ve been … bilingual from a very early age?<br />

13:08 Yes, that’s a good point. Jim Cummins said that there’s a certain<br />

Muiris threshold 45 … there’s a threshold hypothesis that once you’re an<br />

additive bilingual at a certain capacity – so it won’t happen immediately –<br />

some of these advantages to being bilingual accrue as well, in terms of<br />

cognitive development.<br />

13:24 And are there any other advantages as well as the cognitive ones?<br />

Marie<br />

13:28 The cognitive ones … yes, there are indeed, there are the advantages of<br />

Muiris maybe being more imaginative, of seeing the world—as somebody<br />

said—in two different ways, in problem solving, in creativity. But the<br />

strongest evidence that Ellen Bialystock has produced is definitely in<br />

cognitive development. And all the other areas that I just mentioned:<br />

imagination, openness, seeing the world in a dual way, are all being<br />

investigated.<br />

44 tagráin (tagrán)<br />

45 tairseach

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

<strong>Part</strong> 2: Language teaching: insights, theories, approaches <strong>and</strong> factors.<br />

13:52 So Muiris I might move on a bit now to start thinking more about teaching<br />

Marie <strong>language</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> I suppose one of the <strong>first</strong> questions that teachers might<br />

be asking: What kind of factors affect how a child acquires a <strong>second</strong><br />

<strong>language</strong>? Things like the child’s <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>, or the <strong>language</strong> in the<br />

community, or intellectual ability 46 , what kind of factors 47 would be<br />

affecting it?<br />

14:13 That’s a very good question <strong>and</strong> research at the moment is focusing very<br />

Muiris much on those factors, like the child’s background, their <strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>,<br />

things you just mentioned, the <strong>language</strong> the child hears in the<br />

environment, the intellectual ability, the amount of time spent learning is<br />

one – they definitely affect the <strong>acquisition</strong> of <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong>.<br />

Research, I think, is coming more <strong>and</strong> more to the conclusion that what<br />

they call individual factors 48 play a very important role in <strong>language</strong><br />

learning; quite a lot of books now on what’s called the individual factor in<br />

<strong>language</strong> learning. Even we know that learners within the same family,<br />

they often differ greatly in the degree of success they achieve when<br />

learning the <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong>. So they [researchers] have categorised all<br />

these individual factors into two big categories.<br />

One—cognitive factors. They talk there about intelligence, <strong>language</strong><br />

aptitude 49 <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> learning strategies 50 .<br />

And then importantly as well, <strong>and</strong> sometimes overlooked in research up<br />

to now, the affective factors 51 , like the <strong>language</strong> attitudes, the attitudes<br />

they’d have to the speakers of the <strong>language</strong>, motivation, the <strong>language</strong><br />

anxiety 52 (sometimes when learners are called upon to produce<br />

<strong>language</strong> they can become anxious, is the <strong>language</strong> correct) <strong>and</strong> then at<br />

the other end of the scale a thing called the willingness to<br />

communicate 53 : that in certain groups – if you take a group of 20<br />

learners – some of those are more willing to communicate than others,<br />

<strong>and</strong> they’re investigating those what’s called WTC – willingness to<br />

communicate factor in <strong>second</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>.<br />

In the past 20 years though only, Marie, are researchers turning to these<br />

<strong>and</strong> seeing them as extremely important in developing theories of <strong>second</strong><br />

<strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong>.<br />

15:50 So another question then that would spring to mind is that at the very<br />

Marie start of the podcast you mentioned how <strong>language</strong> learning <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong><br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> are at two ends of a spectrum of development 54 . What’s the<br />

role of formal <strong>language</strong> teaching on that spectrum?<br />

16:06 That’s a very very good question. Because when Chomsky <strong>and</strong> Krashen<br />

Muiris <strong>and</strong> all these theorists came out in the seventies <strong>and</strong> said Well, look,<br />

<strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong> is a very natural thing, then it called into question<br />

Well, what can a teacher do, really, in a classroom if <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong><br />

occurs naturally, occurs subconsciously?<br />

Now I think that communicative <strong>language</strong> teaching 55 plays an<br />

enormous role here <strong>and</strong> the syllabi in Irish <strong>language</strong> is the cur chuige<br />

cumarsáide, the communicative <strong>language</strong> teaching. The theory here is<br />

very interesting: that if learners engage meaningfully in communication,<br />

then <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong> occurs almost subconsciously – they’re not<br />

aware they’re learning.<br />

46 cumas intleachtúil<br />

47 tosca (toisc)<br />

48 tosca an duine<br />

aonair<br />

49 inniúlacht/mianach<br />

teanga<br />

50 straitéisí foghlama<br />

teanga<br />

51 tosca<br />

mothachtálacha<br />

52 buairt/imní<br />

53 fonn cumarsáide<br />

54 speictream/<br />

contanam na<br />

forbartha<br />

55 cur chuige na<br />

cumarsáide i<br />

múineadh teangacha

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

Also sometimes when learners are learning subjects through the medium<br />

of the target <strong>language</strong> – it’s called CLIL, Content <strong>and</strong> Language<br />

Integrated Learning 56 – this occurs too. They’re not actually focusing on<br />

learning the <strong>language</strong>, but they’re focusing on doing something through<br />

the <strong>language</strong>, then that actually fuels <strong>and</strong> drives <strong>language</strong> <strong>acquisition</strong> as<br />

well.<br />

17:10 And we actually have another podcast, all about the communicative<br />

Marie approach, with Dr. Kènia Puig i Planella, which is also available on the<br />

website www.action.ncca.ie.<br />

Now Muiris, earlier you were talking about the developmental stages, <strong>and</strong><br />

you were just mentioning there how the teacher is a facilitator 57 in<br />

facilitating this <strong>acquisition</strong>, so how does the teacher go about<br />

sequencing 58 the tasks <strong>and</strong> sequencing the <strong>language</strong> that the children<br />

are learning?<br />

17:39 Remember what I was saying earlier that we’re not fully fully convinced of<br />

Muiris the research yet, because it’s still … experimental, but if there is a<br />

developmental stage then how we actually prepare our <strong>language</strong> learning<br />

materials to fit in with that would be crucial. However, research also is<br />

showing that <strong>language</strong> learning isn’t linear 59 – it doesn’t [necessarily]<br />

happen in that developmental sequence I was just talking about. And we<br />

all know that too, in our classroom one day a learner might produce a<br />

form which is absolutely correct, <strong>and</strong> then, maybe a couple of weeks later<br />

or a month later, they can produce that form again totally incorrectly. So<br />

when this happens then, what’s happening is that maybe the<br />

inter<strong>language</strong> system is being incorporated.<br />

18:24 And what about mistakes? I mean – should I be correcting the children to<br />

Marie try <strong>and</strong> move them on to the next stage, or should I never correct them?<br />

Should I correct them some of the time?<br />

Muiris That’s another good question. These are the questions that constantly we<br />

want to know as teachers Am I doing the right thing, should I correct?<br />

Well, the thinking is that there are two types of correction. There’s<br />

explicit correction 60 : that if a learner makes an error that you correct the<br />

error immediately <strong>and</strong> you bring the learner’s attention to the error. So if<br />

somebody says, for example, An dtaitníonn sé leat? <strong>and</strong> they say Sea,<br />

that you would correct that as No, you say Ní thaitníonn, ní deir tú ‘sea’,<br />

ní thaitníonn nó taitníonn. That’s what’s called explicit [correction].<br />

The other is implicit 61 [correction]. Now a lot of teachers use that:<br />

implicit, or recasts 62 . So again if you say An dtaitníonn sé leat <strong>and</strong> a<br />

learner replies Sea that the teacher would say Ó, taitníonn sé leat? <strong>and</strong><br />

then from that the learner might infer Look, I’ve made a mistake, <strong>and</strong> this<br />

is the right for’. So you’re not drawing attention to the error but you are<br />

giving the right form.<br />

Now again the jury is out in research on that – on both types. Actually,<br />

both might be of very little value unless the learners notice that they’ve<br />

made an error. To give you an example, if I said Tá an carr ar an<br />

mbóthar, learners at a stage of developing will hear the words carr <strong>and</strong><br />

bóthar, <strong>and</strong> they underst<strong>and</strong> from that, particularly in meaningful<br />

communication; they get the idea: carr … bóthar. But at inputprocessing<br />

stage 63 they may not even notice m before the b – mbóthar<br />

– or they may not even notice Tá at all. So it can take a long time for<br />

learners sometimes to actually notice correct forms. I think time is crucial.<br />

56 Foghlaim<br />

Chomhtháite Ábhar<br />

agus Teangacha<br />

57 éascaitheoir<br />

58 seicheamhú<br />

59 líneach<br />

60 léircheartú /ceartú<br />

follasach<br />

61 ceartú intuigthe<br />

62 ateilgean<br />

63 céim próiseála<br />

ionhuir

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

So to answer your question, yes, I think we must constantly give the<br />

correct form, but do not be discouraged if it takes learners longer<br />

sometimes to arrive at the correct form; they will in time, it’s just that<br />

maybe they’re not noticing those correct forms - no matter how often it’s<br />

heard, they notice when their inter<strong>language</strong> is almost ready for that<br />

noticing.<br />

20:32 That’s a very interesting point Muiris, because it’s probably a source of<br />

Marie frustration for a lot of teachers, maybe particularly with written work,<br />

where they’re correcting things, <strong>and</strong> correct the same things over <strong>and</strong><br />

over <strong>and</strong> never see any changes; that it’s all about when the learner<br />

notices <strong>and</strong> that’s where the importance lies, not in the correcting or not<br />

correcting, of the mistake.<br />

20:53 Absolutely. One way to get learners to actually improve their <strong>language</strong><br />

Muiris skills is to get them to notice very very good <strong>language</strong>. So if they could<br />

hear somebody, or see a piece written, that’s at a stage better than their<br />

own stage of development, <strong>and</strong> ask them to reflect on Why is that better?<br />

What do you notice as being very good about this? then once noticing is<br />

activated <strong>and</strong> triggered, actual <strong>acquisition</strong> might occur.<br />

21:27 And that brings up then the question of <strong>language</strong> awareness 64 <strong>and</strong><br />

Marie getting children to notice features 65 about <strong>language</strong><br />

21:30 Yes, absolutely, <strong>and</strong> I think that the more we can make our learners<br />

Muiris curious about <strong>language</strong>, <strong>and</strong> we have wonderful opportunities sometimes<br />

in our classrooms with speakers of other <strong>language</strong>s than English as a<br />

<strong>first</strong> <strong>language</strong>; get them aware that people pronounce 66 words<br />

differently, there are different sounds in <strong>language</strong>, you can actually ask<br />

the children to say some words, to try <strong>and</strong> get children to repeat these<br />

words from Russian or Arabic or French or whatever, <strong>and</strong> that makes<br />

them very curious; that’s a very simple <strong>language</strong> awareness task. So we<br />

can’t just simply assume that because they hear <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> they see<br />

it, <strong>and</strong> they use it, that they actually notice the correct forms.<br />

22:05 And I suppose another crucial point then is the post-communicative<br />

Marie stage 67 of communicative <strong>language</strong> lessons where you actually explicitly<br />

focus on features or errors …<br />

Muiris Absolutely, <strong>and</strong> that can be done sometimes by reflection, saying How<br />

did you get on? What did you find easy, what did you find difficult? Postcommunicative<br />

or post-task <strong>language</strong> teaching, you know you have your<br />

pre-task where they prepare the <strong>language</strong>, they do the task<br />

communicatively <strong>and</strong> in the post-task stage you’re focusing on How well<br />

did you do it? Did you notice anything difficult? Did you notice anything<br />

you did well? Always. If you were to ask somebody else to do it – maybe<br />

a native speaker – this is what they might say <strong>and</strong> get them to notice it, at<br />

various levels of ability. But also encouragement, all the other<br />

educational principles obviously apply in <strong>language</strong> teaching as well.<br />

64 feasacht teanga<br />

65 gnéithe teangacha/<br />

comharthaí sóirt<br />

teangacha éagsúla<br />

66 fuaimniú<br />

67 tréimhse<br />

iarchumarsáideach

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

Cuid 3: Sealbhú agus múineadh na Gaeilge/<strong>acquisition</strong> <strong>and</strong> teaching of Irish<br />

22:53 Agus ag bogadh ar aghaidh anois a Mhuiris, chun díriú isteach go 68 specifically<br />

69 <strong>language</strong><br />

Marie sainiúil 68 ar mhúineadh na Gaeilge agus ceisteanna sealbhaithe<br />

teanga 69 a bhaineann le múineadh na Gaeilge, is dócha gur í an chéad<br />

cheist a ritheann liomsa ná an bhfuil an Ghaeilge níos deacra ná<br />

teangacha eile, le foghlaim nó le múineadh?<br />

23:09 Ceist mhaith agus tá sí minic cloiste agam. Níl aon fhianaise 70 go bhfuil<br />

Muiris a leithéid fíor ach ceaptar a leithéid go mionmhinic. Cinnte, dearfa, tá<br />

gnéithe 71 áirithe a bhaineann leis an nGaolainn 72 nach bhfuil a leithéid<br />

againn sa Bhéarla: cuir i gcás an séimhiú, an t-urú 73 , an rud seo, an<br />

t-infhilleadh 74 (athruithe ar fhocail agus mar sin de) agus tá an forainm<br />

réamhfhoclach 75 (agam, agat, orm, ort) rud atá acu, dála an scéil, sa<br />

Pholainnis agus sa Rúisis. Dá mbeadh teanga Cheilteach eile againn<br />

mar mháthairtheanga 76 , a mbeadh na gnéithe sin ag baint léi, bheadh<br />

sé níos fusa. Tá ar deireadh rud ar a nglaonn siad ansin psychotypology<br />

nó typology 77 : is é sin má labhraíonn tú teanga amháin mar theanga<br />

dhúchais 78 agus tú ag foghlaim teanga eile atá gaolmhar (a bhaineann<br />

leis an gclann chéanna teangacha) ansin ar ndóigh tá sé níos fusa. Ach<br />

tá difríochtaí idir córas an Bhéarla agus córas na Gaeilge agus níor<br />

mhiste ansin b’fhéidir … bhíomar ag caint ó chianaibh 79 ar cheachtanna<br />

feasachta teanga, <strong>language</strong> awareness, caithfimid iad sin a bhunú níos<br />

mó ar na difríochtaí sin.<br />

24:14 Ach é sin ráite, mar a deir tú, ní hí go bhfuil sí [an Ghaeilge] i bhfad níos<br />

Marie deacra agus gach rud atá fíor ó thaobh sealbhú teangacha 80 eile de, tá<br />

sé fíor i dtaobh na Gaeilge freisin?<br />

24:24 Díreach é. Níl sí níos deacra, agus gach aon rud a dúirt (mé) ansin ó<br />

Muiris chianaibh mar gheall ar shealbhú teanga ó thaobh na dteangacha eile de<br />

bheadh sé fíor chomh maith i leith na Gaolainne.<br />

24:36 Agus is dócha, ceist eile ansin a thagann chun cinn go minic ná go bhfuil<br />

Marie sé ráite go soiléir i gcuraclam na Gaeilge gur cheart na ceachtanna a<br />

mhúineadh trí mheán na Gaeilge 81 . Agus uaireanta bíonn sé sin deacair<br />

ar mhúinteoirí, mura bhfuil a gcuid Gaeilge féin chomh líofa 82 agus atá an<br />

Béarla acu. Cén fáth a ndeirtear sin, agus cén fáth a gcaithfimid bheith<br />

dian uaireanta ar na páistí agus a bheith ag iarraidh an Ghaeilge a<br />

ghríosadh 83 uathu.<br />

25:00 Bhuel, anois, níl an oiread sin den bheotheanga 84 , b’fhéidir, acu sa<br />

Muiris timpeallacht 85 is a bheifeá ag súil leis – bhuel, braitheann sé anois: má<br />

tá tú i dtimpeallacht na Gaeltachta agus mar sin de tá an bheotheanga<br />

sin timpeall ort. Ba cheart an oiread [agus is féidir] den bheo teanga sin<br />

a úsáid sa timpeallacht, i dtreo is go mbeadh an rud ar a dtugann siad<br />

ionchur (input) saibhir teanga ann.<br />

Mar sin, tá sé tábhachtach go labhraímid Gaolainn leo an oiread agus is<br />

féidir 86 nó go gcloisfidís an Ghaolainn oiread agus is féidir i rith an lae.<br />

Agus rud amháin, tá sé an-tábhachtach go dtuigfeadh na foghlaimeoirí é<br />

sin. Go minic, déanaimid é sin, ach an dtuigeann na foghlaimeoirí cad ina<br />

thaobh go mbíonn na ceachtanna as Gaolainn? B’fheidir .. ní thuigeann<br />

siad cad chuige a bhfuil an Béarla le seachaint 87 ?<br />

<strong>acquisition</strong> issues<br />

70 no evidence<br />

71 features<br />

72 Gaeilge (in Munster<br />

dialect)<br />

73 eclipis<br />

74 inflection<br />

75 prepositional<br />

pronouns<br />

76 mother tongue<br />

77 típeolaíocht<br />

78 native (<strong>first</strong>)<br />

<strong>language</strong><br />

79 a while ago<br />

80 <strong>language</strong>(s)<br />

<strong>acquisition</strong><br />

81 through the<br />

medium of Irish<br />

82 fluent<br />

83 urge/incite<br />

84 living <strong>language</strong><br />

85 in the environment<br />

86 as much as<br />

possible<br />

87 to be avoided

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

Agus ar ndóigh, má thuigeann siad gur chuid den fhorbairt 88 agus gur<br />

chuid den sealbhú teanga é an bheotheanga sin a chlos agus a úsáid sa<br />

timpeallacht teanga b’fhéidir go gcabhródh sé sin leo ó thaobh<br />

spreagadh 89 agus mar sin de.<br />

Tá sé an-tábhachtach chomh maith go mbeifeá féin, mar mhúinteoir, ar<br />

do chompord 90 leis an teanga agus go mbainfí úsáid aisti mar<br />

bheotheanga chumarsáide 91 sa seomra ranga, agus ar ndóigh chomh<br />

minic agus is féidir lasmuigh de. Ba dheas liom go gcífeadh múinteoirí<br />

b’fhéidir, agus foghlaimeoirí, go mbaineann an teanga, ní hamháin leis an<br />

seomra ranga, ach leis an ngnáthshaol laethúil 92 lasmuigh den seomra<br />

ranga, agus arís tá an fheasacht teanga an-tábhachtach chuige sin.<br />

Féadann tú a rá leo Tá mise dátheangach 93 , tá dá theanga agam,<br />

Béarla-Gaeilge. Agus ansin dá mbeadh daoine eile, b’fhéidir, sa rang a<br />

mbeadh dá theanga acu chomh maith, Polainnis-Béarla nó rud éigin mar<br />

sin, d’fhéadfá é sin a úsáid le cur ar a súile dóibh gur rud iontach é seo,<br />

an dátheangachas 94 .<br />

26:47 Agus ag caint ansin ar an dátheangachas, agus ar an ionchur teanga nó<br />

Marie <strong>language</strong> input, ar cheart mar sin go mbeadh páistí ag éisteacht le<br />

cainteoirí dúchas 95 ?<br />

26:58 Ba cheart. Ba cheart go gcloisfidís raon leathan 96 de chainteoirí dúchais<br />

Muiris agus cainteoirí dara teanga. Ar ndóigh bheadh sé deacair, go háirithe<br />

nuair a thagann sé go canúintí 97 , b’fhéidir, nach mbeadh fiú cur amach<br />

iomlán ag múinteoirí orthu go minic, ach mar sin féin, leis na difríochtaí<br />

sin canúna 98 , na difríochtaí sin foghraíochta 99 : a mhíniú dóibh agus a<br />

rá Bíonn sé seo i ngach aon teanga. Tarlaíonn sé sin leis an mBéarla fiú,<br />

dá rachfá maidin amárach chuig Sasana, tá áiteanna ansin b’fhéidir nach<br />

dtuigfeá an cineál Béarla atá iontu go tapaidh.<br />

Ach mar sin féin tá sé an-tábhachtach go dtuigfeadh siad go bhfuil a<br />

leithéid de rud agus cainteoir dúchais ann, agus go bhfuil cainteoirí<br />

dúchais óg agus aosta [ann], agus fiú dá mbeadh cartúin, ar TG4 agus<br />

mar sin, gur féidir cuid díobh sin a úsáid fiú (cuid de na carachtair a<br />

bheadh ansin sna cartúin ar cainteoirí dúchas iad sin) chun aird na<br />

bhfoghlaimeoirí 100 a tharraingt air sin. B’fhéidir nach dtuigfidís, ach de<br />

réir a chéile 101 … ní sheachnóinn in aon chor an cainteoir dúchais cé go<br />

bhfuil dúshlán ag baint leis – ní sheachnóinn 102 é san ionchur teanga<br />

sin.<br />

27:59 Agus luaigh tú canúintí agus b’fhéidir sa Bhéarla go mbíonn canúintí ann<br />

Marie freisin cé nach smaoinímid air sin, an bhfuil aon chomhairle 103 agat do<br />

mhúinteoirí maidir le canúintí agus conas déileáil leo siúd?<br />

28:11 Arís ceist mhaith. An phríomhchomhairle 104 , is dóigh liom, a chuirfinn ar<br />

Muiris mhúinteoirí ná bheith chomh nádúrtha agus is féidir. Mar cuimhnigh gur<br />

chuig cumarsáid 105 í an teanga tar éis an tsaoil 106 . Agus is iomaí cineál<br />

cainteora atá ann. Dá mbeifeá ag obair i scoil Ghaeltachta, ar ndóigh,<br />

bheadh an-bhéim ar an gcanúint logánta 107 nó áitiúil. Ach mar a dúirt,<br />

b’fhiú cur ar a súile 108 d’fhoghlaimeoirí go bhfuil foghraíocht 109 ar leith<br />

ag baint leis an nGaeilge sa tslí chéanna ina bhfuil foghraíocht ag baint<br />

leis an bPolainnis nó ag Araibis nó an Fhraincis. Ach an príomhrud ná<br />

bheith chomh nádúrtha, chomh cumarsáideach agus is féidir sa treo is go<br />

dtuigfidís gur seo teanga chumarsáideach, agus bheith chomh nádúrtha<br />

agus is féidir laistigh de sin.<br />

88 of development<br />

89 motivation<br />

90 comfortable<br />

91 living means of<br />

communication<br />

92 with everyday life<br />

93 bilingual<br />

94 bilingualism<br />

95 native speakers<br />

96 wide range<br />

97 dialects<br />

98 those dialectical<br />

differences<br />

99 those phonetic<br />

differences<br />

100 the learners<br />

attention<br />

101 by degrees<br />

102 I wouldn’t avoid<br />

103 any advice<br />

104 the main advice<br />

105 communication<br />

106 in the end of the<br />

day<br />

107 local<br />

108 to make (learners)<br />

aware of<br />

109 phonetics

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

28:51 Agus an gceapann tú, a Mhuiris, go bhfuil cur chuige éagsúil 110 ag<br />

Marie teastáil ansin má tá duine ag múineadh i scoil Ghaeltachta?<br />

29:00 Or ar ndóigh tá. Mar bheadh an teanga ansin ar a dtoil 111 , ní ag gach<br />

Muiris páiste, ach ag an-chuid de na páistí. An príomhrud ná dúshlán 112 na<br />

bhfoghlaimeoirí ag an bpointe sin a thabhairt. Má tá siad siúd ag obair ar<br />

théacsanna 113 nó mar sin atá ag leibhéal ró-íseal dóibh ní spreagfaidh<br />

sé sin iad. Mar a dúirt Krashen fadó, caithfidh an t-ionchur teanga a<br />

bheith ag leibhéal amháin chun tosaigh 114 ar chumas na<br />

bhfoghlaimeoirí.<br />

Agus ansin sa Ghaeltacht b’shin an prionsabal a bheadh i gceist.<br />

Caithfidh an t-ionchur teanga a bheith saibhir sna seomraí ranga ar fad,<br />

ach sa Ghaeltacht caithfidh sé bheith ag leibhéal chun tosaigh [ar<br />

Ghaeilge na bpáistí] agus bheith chomh saibhir agus is féidir. Cur chuige<br />

eile mar sin dáiríre, dhíreofá ansin b’fhéidir ar stór leathan foclóra 115 ,<br />

réimse leathan cora cainte 116 agus leaganacha 117 , comhchiallacha 118<br />

agus mar sin de, a thabhairt dóibh a luaithe agus is féidir.<br />

29:55 Agus an teoiric sin mar gheall ar dhúshlán na bpáistí a thabhairt? An<br />

Marie bhfuil sé sin fíor do sheomraí ranga eile freisin, nach bhfuil cainteoirí<br />

dúchais iontu?<br />

30:03 Tá. Ceist an-mhaith í sin. Ní bhaineann sé le cainteoirí dúchais amháin.<br />

Muiris Sin fíor maidir le daltaí agus le foghlaimeoirí i gcoitinne. Cuir i gcás dá<br />

mbeadh seanchleachtadh 119 ag na daltaí ar na gnáthrudaí, abair<br />

gnáthbheannachtaí 120 , Conas tá tú, cá bhfuil cónaí ort, cén aois tú?<br />

agus go bhfuil sé sin acu, abair, agus seantaithí acu [orthu].<br />

Dá dtosóidís air sin arís, sa mheánscoil, (dá bhféadfainn an mheánscoil a<br />

lua anseo) an chéad lá nó an dara lá nó an chéad mhí nó mar sin,<br />

b’fhéidir go ndéarfaidís leo féin ansin Bhuel, an bhfuil aon dul chun<br />

cinn 121 ar siúl agam maidir leis an nGaolainn? Caithfidh tú cur ar a súile<br />

dóibh go gcaithfidh siad dul chun cinn a dhéanamh, go gcaithfidh tú, mar<br />

a dúraís ansin, a ndúshlán a thabhairt i gcónaí trí théacsanna atá leibhéal<br />

amháin níos casta ná an teanga atá sealbhaithe acu cheana féin.<br />

30:52 Agus as sin ardaítear ceisteanna mar gheall ar dul siar, mar chun dul<br />

Marie chun cinn a dhéanamh, ní mór dul siar 122 freisin. Agus éiríonn na páistí,<br />

mar a dúirt tú, bréan de 123 bheith ag dul siar ar rudaí céanna? Conas is<br />

féidir tabhairt faoi sin, n’fheadar?<br />

31:07 Tá an dul siar nó an t-athdhéanamh 124 sin thar a bheith tábhachtach,<br />

Muiris ach dá bhféadfá, b’fhéidir, é a dhéanamh i slite úra 125 , abair, seachas<br />

bheith ag druileáil agus an dul siar agus an t-athrá 126 arís. Go mbainfidís<br />

úsáid as, b’fhéidir, dráma beag, nó go gcuirfidís rud éigin le chéile<br />

bunaithe ar na focail agus ar na leaganacha atá á gclos acu ar feadh na<br />

seachtaine nó ar feadh na míosa.<br />

Mar sin dúshlán an-mhór …. mar dá mhéad uair a úsáidfidh foghlaimeoirí<br />

focal nua/téarma nua/cora cainte nua – i gcomhthéacsanna nua chomh<br />

maith – is amhlaidh is fusa a shealbhóidh siad sin. Tá an dul siar thar a<br />

bheith tábhachtach, ach cuimhnigh ar shlite úra nua cruthaitheacha 127<br />

ina bhféadfadh páistí na focail, na leaganacha atá sealbhaithe, nó<br />

foghlamtha acu, a úsáid arís.<br />

110 a different<br />

approach<br />

111 to be fluent in<br />

112 challenge<br />

113 texts<br />

114 ahead of<br />

115 wide vocabulary<br />

116 idioms<br />

117 forms of speech<br />

(idioms)<br />

118 synonyms<br />

119 strong familiarity<br />

120 ordinary greetings<br />

121 progress<br />

122 revise, go back<br />

over<br />

123 tired of, bored with<br />

124 revision<br />

125 new ways<br />

126 the repetition<br />

127 creative

Transcríbhinn: Podchraoladh – Sealbhú teanga<br />

31:55 Tuigim. Agus a Mhuiris, bhíomar ag caint níos túisce ansin mar gheall ar<br />

Marie earráidí 128 , agus ceartú earráidí agus mar sin de. An bhfuil aon saghas<br />

moltaí breise maidir le múineadh na Gaeilge, gramadach na Gaeilge,<br />

agus mar sin de, le cur leis an méid a bhí ráite cheana?<br />

32:10 Bhuel, arís déanaim tagairt don idirtheanga sin – gur cuid den fhorbairt<br />

Muiris nádúrtha agus de phróiseas an tsealbhaithe [é]. Tá sé tábhachtach na<br />

mórbhotúin 129 a cheartú cinnte, i dtreo is nach bhfanfadh na botúin sin<br />

reoite 130 . Agus arís bheith an-fhoighneach 131 ar fad, mar go dtógann sé<br />

an-chuid ama … gan misneach a chailliúint. Agus go minic bímid cráite<br />

nuair a bhíonn rudaí múinte – mar a thuigimid – i gceart againn, agus<br />

mar sin de, nach bhfuil siad sealbhaithe. Agus cuimhnigh ar na<br />

difríochtaí aonair 132 sin a mhaireann idir foghlaimeoirí. Is dóigh liom gur<br />

sin iad na léargais ón teangeolaíocht fheidhmeach 133 agus ó shealbhú<br />

an dara teanga a thugann, is dóigh liom, sólás dúinn mar mhúinteoirí mar<br />

tuigimid gur próiseas casta é próiseas an tsealbhaithe 134 . Agus má<br />

leanaimid orainn, le cúrsaí ama agus le spreagadh, agus leis an rud a<br />

dhéanamh chomh cruthaitheach agus is féidir agus chomh fuinniúil 135<br />

agus is féidir, éireoidh linn ar ball.<br />

33:04 Agus is deas an nóta dóchais é sin. Anois, is dócha go bhfuilimid ag<br />

Marie druidim chun deiridh, ach an bhfuil aon rud breise ar mhaith leat a rá faoi<br />

shealbhú teanga agus múineadh teangacha?<br />

33:15 Is dóigh liom gur an é rud is mó a chabhraigh liomsa féin ná gur thug sé<br />

Muiris léargas áirithe 136 dom. Go minic bhíos ag cur an mhilleáin 137 orm féin<br />

mar mhúinteoir agus ag rá Cad ina thaobh a bhfuil siad ag déanamh na<br />

mbotún? agus níor thuigeas an rud seo faoi idirtheanga. Níor thuigeas,<br />

mar shampla, na difríochtaí idir foghlaimeoirí agus mar sin de. Tugann sé<br />

cineál breismhisnigh 138 do mhúinteoirí agus sin, is dócha, an nóta<br />

dóchais ar mhaith liom tagairt dó ag deireadh an agallaimh seo.<br />

33:42 Agus is deas é sin mar chríoch don agallaimh. A Mhuiris, go raibh míle<br />

Marie maith agat.<br />

Muiris Míle fáilte romhat.<br />

128 errors<br />

129 the main errors<br />

130 frozen (fossilised)<br />

131 very patient<br />

132 individual<br />

differences<br />

133 applied linguistics<br />

134 the <strong>acquisition</strong><br />

process<br />

135 energetic<br />

136 a certain insight<br />

137 blaming<br />

138 a certain amount<br />

of extra courage