You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The wonders of tick-spit<br />

by Pat Nuttall (JRF 1977–80, RF 1990–95, GB 1995–<br />

2001; SF 2001–)<br />

Have you ever been bitten by a tick? If you have, you probably didn’t feel a thing.<br />

Maybe you only noticed the little black speck attached to your skin after it had<br />

started feeding, growing fatter as it sucked your blood.<br />

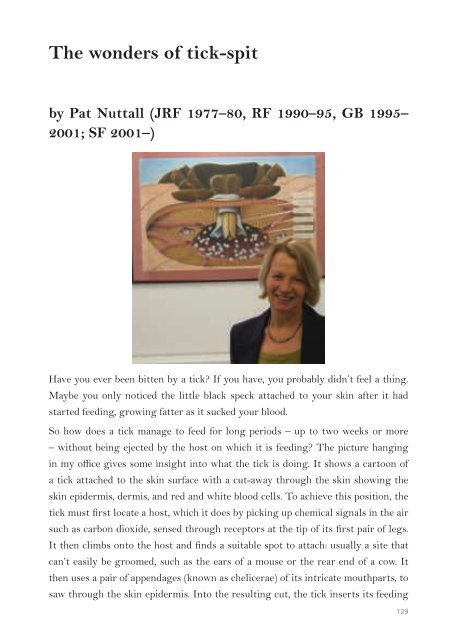

So how does a tick manage to feed for long periods – up to two weeks or more<br />

– without being ejected by the host on which it is feeding? The picture hanging<br />

in my office gives some insight into what the tick is doing. It shows a cartoon of<br />

a tick attached to the skin surface with a cut-away through the skin showing the<br />

skin epidermis, dermis, and red and white blood cells. To achieve this position, the<br />

tick must first locate a host, which it does by picking up chemical signals in the air<br />

such as carbon dioxide, sensed through receptors at the tip of its first pair of legs.<br />

It then climbs onto the host and finds a suitable spot to attach: usually a site that<br />

can’t easily be groomed, such as the ears of a mouse or the rear end of a cow. It<br />

then uses a pair of appendages (known as chelicerae) of its intricate mouthparts, to<br />

saw through the skin epidermis. Into the resulting cut, the tick inserts its feeding<br />

129