You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Welcome • ohtcv ohfurc<br />

Shabbat Shalom • ouka ,ca<br />

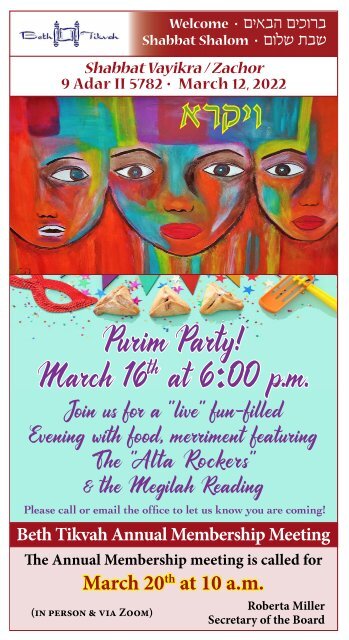

Shabbat <strong>Vayikra</strong> / Zachor<br />

9 Adar II 5782 • March 12, 2022<br />

trehu<br />

Purim Party!<br />

March 16 th at 6:00 p.m.<br />

Join us for a "live" fun-filled<br />

Evening with food, merriment featuring<br />

The "Alta Rockers"<br />

& the Megilah Reading<br />

Please call or email the office to let us know you are coming!<br />

Beth Tikvah Annual Membership Meeting<br />

The Annual Membership meeting is called for<br />

March 20 th at 10 a.m.<br />

(in person & via Zoom)<br />

Roberta Miller<br />

Secretary of the Board

A<br />

Mar 11<br />

Mar 12<br />

Mar 13<br />

Mar 14<br />

Mar 18<br />

We mourn the passing of<br />

Stephen Brazina k ”z<br />

Beloved husband of Rhonda Brazina<br />

May His Memory Be for a Blessing • lurc urfz hvh<br />

Birthdays<br />

Donations in his memory may be made to the<br />

Beth Tikvah Chesed Fund.<br />

Ruth Bier<br />

Roberta Miller, Genesis Sando<br />

Aaron Cohen<br />

Arlene Sobol, Jill Valesky<br />

Alex Wertheim<br />

Kiddush Sponsors<br />

Bob & Shelley Goodman,<br />

In honor of Shelleys's Birthday!<br />

Michael & Sharon Gertz,<br />

A<br />

jna ,skuv ouh<br />

In honor of the wonderful Congregants of<br />

Beth Tikvah. Thank you for being so warm and<br />

welcoming!<br />

Kiddush Maven Linda Scheinberg<br />

Assisted by Rosalee Bogo, Judith Chaloff, Sue Hammerman,<br />

Evelyn & Larry Hecht, Elaine Kamin, Judy Levitt,<br />

Paulette Margulies, Shep Scheinberg & Dave Sivakoff<br />

To sponsor a kiddush, please contact Linda Scheinberg<br />

missus205@gmail.com<br />

– Shelley Goodman<br />

Do you make plans? Do you expect them to be actualized?<br />

Living with Covid-19 taught all of us how fragile plans<br />

really were. If asked in March 2020 what we had planned<br />

for summer 2020 we all would have been wrong. Our experiences<br />

validated that we are “Living in the Unpredictable.” Come and<br />

listen to my journey, the skills I learned and now practice in order to<br />

not only live – but rather thrive in a time of unpredictability.<br />

Lecture Series: Tuesday March 29 th at 7:30<br />

Please join us for Minyan<br />

Friday, March 18 th at 9:00 a.m.

Torah & Haftarah Readings:<br />

Shabbat <strong>Vayikra</strong>h / Zachor: Leviticus 4:27-5:26 (Etz Hayim p. 599)<br />

1. 4:27-31 2. 4:32-35 3. 5:1-10 4. 5:11-13<br />

5. 5:14-16 6. 5:17-19 7. 5:20-26 M. Deut. 25:17-19 (p. 1135)<br />

Haftarah: Samuel 15:2-34 (Etz Hayim p. 1281)<br />

Torah / Haftarah Summary<br />

D'var Torah:<br />

Moshe, Hillel and Frederick the Mouse<br />

Ilana Kurshan<br />

In the transition from Exodus to Leviticus, the Torah shifts from describing<br />

the construction of the Mishkan to describing its operations. At the end<br />

of the book of Exodus, Moshe was in charge of the Mishkan, transmitting<br />

God’s architectural instructions and ensuring that the structure was built<br />

“in accordance with all that God commanded Moshe.” Now, with the start<br />

of Leviticus, the Mishkan becomes the domain of Aaron and the priests,<br />

who are responsible for the system of sacrificial worship. No wonder, then,<br />

that the rabbis imagine Moshe standing off in the wings at the start of our<br />

parashah, unsure of his role and reluctant to resume center stage until<br />

summoned by God. God’s call to Moshe at the start of our parashah is read<br />

by the rabbis as a lesson in the value of humility, which is surprisingly more<br />

about self-assurance than about self-effacement.<br />

The rabbis (Leviticus Rabbah 1:5) pick up on an apparent redundancy in the<br />

opening verse of our parashah: “The Lord called to Moshe and spoke<br />

to him from the Tent of Meeting” (1:1). If the Torah tells us that the<br />

Lord “called” to Moshe, why does it also have to state that the Lord “spoke”<br />

to him? Aren’t these verbs essentially synonymous? The midrash explains<br />

that Moshe was standing off to the side and thus God had to first call him<br />

over before speaking to him, saying, “For how long will you keep yourself<br />

low? The time waits but for you!” The rabbis contend that this is the same<br />

posture Moshe adopted at the burning bush, when he hid his face from<br />

God; as per the midrash, it is also the posture he adopted at the Red Sea,<br />

when God said, “If you do not split the sea, no one else will,” and then again<br />

at Sinai, when God had to call Moshe up the mountain. The rabbis present<br />

Moshe as a model of humility, concluding that one ought to “go two or three<br />

seats lower and take your seat. Better that people should say to you: Come<br />

up, come up, and not say to you: Go down, go down.” They compare Moshe<br />

to Hillel, who was also famous for his self-effacement, arguing that it is better<br />

to underestimate oneself than to err on the side of self-aggrandizement.<br />

And yet the midrash suggests that as Moshe stands outside the Mishkan<br />

with his head bent and his hands in his proverbial pockets, God has grown<br />

somewhat exasperated with him: “For how long will you keep yourself<br />

low?” This does not seem to be the humility that God desires.

The rabbis explain that Moshe was reluctant to come forward because<br />

he was uncertain as to what he could contribute. He has watched as the<br />

Israelites donated gold and precious stones to the Mishkan, and he doubts<br />

what he can add. “Everyone has brought their voluntary offerings to the<br />

Mishkan, and I have brought nothing” (Leviticus Rabbah 1:6). God, seeing<br />

Moshe’s despondence, said to him, “As you live, your speech is more<br />

beloved to me than all.” Moshe thinks he has nothing to offer, but God<br />

assures him that his eloquence is valued most highly. He is like the mouse<br />

named Frederick in Leo Leonni’s eponymous picture book, whose gift is<br />

not the corn and nuts and wheat and straw that all the other mice gather for<br />

the winter, but the beautiful poem about blue periwinkles and red poppies<br />

which he composes to sing to the other field mice once the days have grown<br />

gray and dark.<br />

Moshe, who has always doubted his powers of speech, is perhaps being<br />

once again reminded that his gifts are not just a reflection of his own innate<br />

talents, but of what God has instilled in him: “Who gives man speech?<br />

Who makes him dumb or deaf, seeing or blind? Is it not I, the Lord?”<br />

(Exodus 4:11). If Moshe denigrates himself too much, he risks denying and<br />

depriving the others of his God-given gifts. After all, it is the very same<br />

Hillel—famous for his humility—who would arrive at the festival of the<br />

water-drawing on Sukkot and say, “If I’m here, everyone is here” (Sukkah<br />

53a). Hillel realized that if he, in spite of his humility, could share his gifts<br />

with the world, then surely everyone else could as well. We are not meant to<br />

lay low and downplay our talents, but to use them to enrich those around<br />

us – like Frederick, who responds to the other mice’s plaudits—“Frederick,<br />

you are a poet!”—by blushing, taking a bow, and saying shyly, “I know it.”<br />

The construction of the Mishkan is frequently analogized to the creation of<br />

the world, with the Mishkan imagined as a Garden of Eden (see, for instance,<br />

Tanchuma Pekudei 2). If so, then we might read God’s first call to Moshe<br />

in our parashah as analogous to God’s first call to Adam in the garden:<br />

“Where are you?” An omniscient God has no need to ask Adam about<br />

his whereabouts; rather, God is asking Adam to take responsibility for his<br />

actions. God does not want Adam to hide away shamefully, just as God<br />

does not want Moshe to stand off to the side with lowered head. Adam,<br />

instilled with the knowledge of good and evil, is being called to repent for<br />

his wrongdoing. And Moshe, instilled with divine powers of speech, is<br />

being called to continue to be a conduit for God’s word. Both must come<br />

forth and own up to what is expected of them.<br />

Like Adam, every human being is created in God’s image and furnished<br />

with God-given gifts. If we can learn neither to flaunt nor to suppress those<br />

gifts, we will internalize the message of the book of Leviticus, namely that<br />

sacrificial worship—like all religious worship—is about giving the best of<br />

ourselves and, in so doing, drawing closer to God.

D'var Haftorah<br />

Can God Change? - Bex Stern Rosenblatt<br />

In the Dvar Haftarah for Ki Tisa, we thought about whether it was possible<br />

for humans to change, how a person could change themselves. In this week’s<br />

haftarah the same question is posed about God. Can God change? Is the<br />

essence of eternity and divinity to never change or to be constantly evolving?<br />

The question of God’s ability to change is posed around the word 'nehem.'<br />

It’s a hard word to translate, a word with many variable meanings. It is used<br />

to mean to have compassion, to be sorry, to regret, to repent, to comfort,<br />

and to be comforted, among other things. The word appears three times<br />

in our haftarah portion, opening and closing the portion and once in the<br />

middle. We read, in verse eleven as translated by Robert Alter: “I repent that<br />

I made Saul king, for he has turned back from Me, and My words he has not<br />

fulfilled.” Likewise, the haftarah closes with verse thirty-five, as translated<br />

by Alter: “the LORD had repented making Saul king over Israel.” But in<br />

between these verses we get a most curious statement. We read in verse<br />

twenty-nine, as translated by Alter, “And, what’s more, Israel’s Eternal does<br />

not deceive and does not repent, for He is no human to repent.”<br />

The story tells us twice of God repenting (or regretting, etc. depending on<br />

how you choose to translate it.) And yet the story also tells us that God does<br />

not repent, that repentance is a uniquely human quality. A repentant God is<br />

a God who changes, a God who can be constantly evolving. In the story of<br />

the haftarah, this makes sense. God had chosen Saul as the first king of Israel<br />

and is now changing course, to anoint David as king. It is a very awkward<br />

transition, with the succession pangs providing most of the material for<br />

the book of Samuel. Surely there could have been a better way to do this. If<br />

God had always wanted David to be king, perhaps God could have skipped<br />

Saul. One could conclude that God must have initially wanted Saul and then<br />

changed God’s mind when Saul failed to do as he was ordered.<br />

So why are we also told that God does not repent, does not change God’s<br />

mind? This creates an image of a God who always had everything in a<br />

divine plan - a God who intended for Israel to go through the mess of Saul’s<br />

kingship in order to get to David’s kingship. This is the sort of God we refer<br />

to when we say things like “everything happens for a reason.” This is the<br />

all-knowing God who has the world’s best interests at heart. But this is not<br />

a God who is responsive to us, who hears humanity and adjusts the divine<br />

plan.<br />

Our haftarah tries to have it both ways - both the responsive God and the<br />

all-knowing God, the flexible God and the fixed God. There is something<br />

wonderful in this paradox, something Godlike, something bigger than we<br />

can understand. The essence of divinity can hold both never changing and<br />

constantly evolving, even if we cannot.

Scholar in reisdence Weekend with<br />

Rabbi Abraham Skorka<br />

April 1 st & 2 nd<br />

Rabbi Abraham Skorka was<br />

born in Buenos Aires. He<br />

holds a PhD in Chemistry<br />

from The University of Buenos Aires, and<br />

graduated from Midrahsa HaIvrit and the Latin-<br />

American Rabbinical Seminary. He was the Rabbi<br />

of the Benei Tikva synagogue for 42 years and the<br />

rector of the Rabbinical Seminary for 20 years.<br />

Rabbi Skorka has been fully committed to<br />

his work in interfaith dialogue. The author of<br />

numerous articles and books, particularly – On<br />

Heaven and Earth - which he wrote with the<br />

Archbishop of Buenos Aires Cardinal Bergoglio,<br />

who is currently Pope Francis.<br />

In addition to many distinguished awards, he has received honorary<br />

doctoral degrees from the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina,<br />

Jewish Theological Seminary and Sacred Heart University.<br />

Rabbi Skorka will address some of the topics<br />

closest and dearest to his heart, during a special<br />

Shabbat of growth and learning:<br />

Friday Evening After Dinner:<br />

"THE PERILS OF POLARIZED<br />

PUBLIC DISCOURSE”<br />

Saturday Morning:<br />

"THE INFLUENCE OF THE PANDEMIC<br />

IN SYNAGOGUE LIFE"<br />

Dinner will begin at 5:30 p.m.<br />

RESERVATIONS FOR THIS EVENT<br />

ARE A MUST!<br />

Cost per person $36 – payment must be received before 3/28<br />

Call Gillian at the office to let her know you are coming!<br />

Beth Tikvah of Naples<br />

1459 Pine Ridge Road<br />

Naples, FL 34109<br />

(239) 434-1818<br />

Visit us online at<br />

bethtikvahnaples.org<br />

or scan the QR code<br />

to go there directly