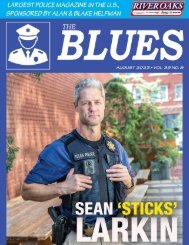

AUG 2022. Blues Vol 38 No. 8.

AUG 2022. Blues Vol 38 No. 8. FEATURES 34 UVALDE - What Really Happened. 42 UVALDE - We Stopped Looking for Heroes 48 COVER - Michelle Cook-True Passion for Service 62 Visit Galveston Island this Summer DEPARTMENTS 6 Publisher’s Thoughts 8 Editor’s Thoughts 10 Guest Commentary - Bill King 14 News Around the US 34 Breaking News 58 Calendar of Events 68 Remembering Our Fallen Heroes 80 War Stories 84 Aftermath 86 Open Road 88 Healing Our Heroes 90 Daryl’s Deliberations 94 HPOU - From the President, Douglas Griffith 96 Light Bulb Award 98 Running 4 Heroes 100 Blue Mental Health with Dr. Tina Jaeckle 102 Ads Back in the Day 106 Parting Shots 108 Buyers Guide 128 Now Hiring - L.E.O. Positions Open in Texas 166 Back Page

AUG 2022. Blues Vol 38 No. 8.

FEATURES

34 UVALDE - What Really Happened.

42 UVALDE - We Stopped Looking for Heroes

48 COVER - Michelle Cook-True Passion for Service

62 Visit Galveston Island this Summer

DEPARTMENTS

6 Publisher’s Thoughts

8 Editor’s Thoughts

10 Guest Commentary - Bill King

14 News Around the US

34 Breaking News

58 Calendar of Events

68 Remembering Our Fallen Heroes

80 War Stories

84 Aftermath

86 Open Road

88 Healing Our Heroes

90 Daryl’s Deliberations

94 HPOU - From the President, Douglas Griffith

96 Light Bulb Award

98 Running 4 Heroes

100 Blue Mental Health with Dr. Tina Jaeckle

102 Ads Back in the Day

106 Parting Shots

108 Buyers Guide

128 Now Hiring - L.E.O. Positions Open in Texas

166 Back Page

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

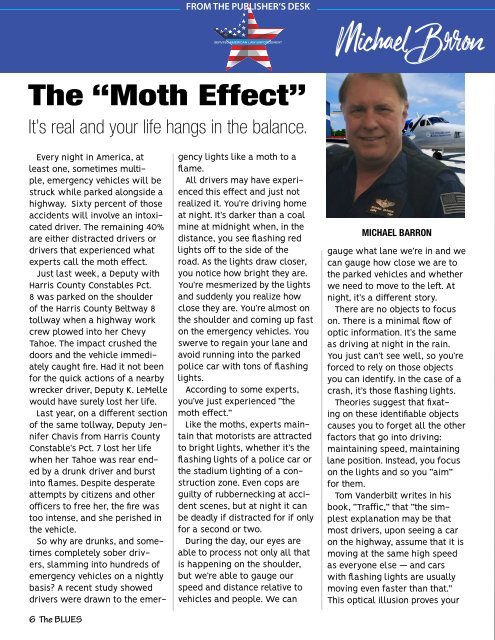

FROM THE PUBLISHER’S DESK<br />

The “Moth Effect”<br />

It’s real and your life hangs in the balance.<br />

Every night in America, at<br />

least one, sometimes multiple,<br />

emergency vehicles will be<br />

struck while parked alongside a<br />

highway. Sixty percent of those<br />

accidents will involve an intoxicated<br />

driver. The remaining 40%<br />

are either distracted drivers or<br />

drivers that experienced what<br />

experts call the moth effect.<br />

Just last week, a Deputy with<br />

Harris County Constables Pct.<br />

8 was parked on the shoulder<br />

of the Harris County Beltway 8<br />

tollway when a highway work<br />

crew plowed into her Chevy<br />

Tahoe. The impact crushed the<br />

doors and the vehicle immediately<br />

caught fire. Had it not been<br />

for the quick actions of a nearby<br />

wrecker driver, Deputy K. LeMelle<br />

would have surely lost her life.<br />

Last year, on a different section<br />

of the same tollway, Deputy Jennifer<br />

Chavis from Harris County<br />

Constable’s Pct. 7 lost her life<br />

when her Tahoe was rear ended<br />

by a drunk driver and burst<br />

into flames. Despite desperate<br />

attempts by citizens and other<br />

officers to free her, the fire was<br />

too intense, and she perished in<br />

the vehicle.<br />

So why are drunks, and sometimes<br />

completely sober drivers,<br />

slamming into hundreds of<br />

emergency vehicles on a nightly<br />

basis? A recent study showed<br />

drivers were drawn to the emer-<br />

gency lights like a moth to a<br />

flame.<br />

All drivers may have experienced<br />

this effect and just not<br />

realized it. You’re driving home<br />

at night. It’s darker than a coal<br />

mine at midnight when, in the<br />

distance, you see flashing red<br />

lights off to the side of the<br />

road. As the lights draw closer,<br />

you notice how bright they are.<br />

You’re mesmerized by the lights<br />

and suddenly you realize how<br />

close they are. You’re almost on<br />

the shoulder and coming up fast<br />

on the emergency vehicles. You<br />

swerve to regain your lane and<br />

avoid running into the parked<br />

police car with tons of flashing<br />

lights.<br />

According to some experts,<br />

you’ve just experienced “the<br />

moth effect.”<br />

Like the moths, experts maintain<br />

that motorists are attracted<br />

to bright lights, whether it’s the<br />

flashing lights of a police car or<br />

the stadium lighting of a construction<br />

zone. Even cops are<br />

guilty of rubbernecking at accident<br />

scenes, but at night it can<br />

be deadly if distracted for if only<br />

for a second or two.<br />

During the day, our eyes are<br />

able to process not only all that<br />

is happening on the shoulder,<br />

but we’re able to gauge our<br />

speed and distance relative to<br />

vehicles and people. We can<br />

MICHAEL BARRON<br />

gauge what lane we’re in and we<br />

can gauge how close we are to<br />

the parked vehicles and whether<br />

we need to move to the left. At<br />

night, it’s a different story.<br />

There are no objects to focus<br />

on. There is a minimal flow of<br />

optic information. It’s the same<br />

as driving at night in the rain.<br />

You just can’t see well, so you’re<br />

forced to rely on those objects<br />

you can identify. In the case of a<br />

crash, it’s those flashing lights.<br />

Theories suggest that fixating<br />

on these identifiable objects<br />

causes you to forget all the other<br />

factors that go into driving:<br />

maintaining speed, maintaining<br />

lane position. Instead, you focus<br />

on the lights and so you “aim”<br />

for them.<br />

Tom Vanderbilt writes in his<br />

book, “Traffic,” that “the simplest<br />

explanation may be that<br />

most drivers, upon seeing a car<br />

on the highway, assume that it is<br />

moving at the same high speed<br />

as everyone else — and cars<br />

with flashing lights are usually<br />

moving even faster than that.”<br />

This optical illusion proves your<br />

assumptions false because the<br />

vehicles are, in fact, stopped.<br />

He also notes that we tend to<br />

look longer at dramatic things,<br />

such as a bad crash, meaning<br />

that the longer we become<br />

distracted, the harder it is to<br />

maintain direction. Researchers<br />

have been studying the effect<br />

for decades, all the way back to<br />

B2 pilots in World War II, who<br />

spoke of becoming fixated on the<br />

lead plane and navigating toward<br />

it.<br />

Today, researchers look at its<br />

effects on motorists.<br />

In 2008, the University of Michigan<br />

Transportation Research<br />

Institute studied the effects of<br />

warning lamp color and intensity<br />

on driver vision. Variables<br />

included color and intensity of<br />

light.<br />

Participants were asked to<br />

differentiate, as quickly as possible,<br />

whether the flashing lights<br />

were on the right or left side<br />

of an emergency vehicle. They<br />

were then asked to differentiate<br />

whether an emergency responder<br />

was standing on the right or<br />

left side of the vehicle.<br />

As expected, participants were<br />

better able to differentiate the<br />

lights at night and the pedestrians<br />

during the day. When color<br />

was added to the equation, blue<br />

markings were the most easily<br />

distinguishable, followed by yellow,<br />

red and white.<br />

Researchers suggested equipping<br />

all emergency vehicles<br />

with blue lights, as is common<br />

in Europe. They also suggested<br />

that blue lights might prevent<br />

the moth effect, in which drivers<br />

would mistake red lights for vehicle<br />

taillights and follow them<br />

off the road and into the emergency<br />

personnel.<br />

According to the ODMP website,<br />

31 police officers were<br />

struck by vehicles and killed<br />

while directing traffic or assisting<br />

motorists to date in <strong>2022.</strong><br />

There were 61 in 2021 and 46 in<br />

2020.<br />

“The moth effect may be a pop<br />

phrase, but the phenomenon is<br />

real,” said Jack Sullivan, director<br />

of training for the Cumberland<br />

Valley (Va.) <strong>Vol</strong>unteer Firemen’s<br />

Association’s Emergency Responder<br />

Safety Institute and one<br />

of the nation’s leading experts.<br />

Regardless of what you call<br />

it, every time you work an accident,<br />

make a traffic stop or<br />

just park on a highway at night,<br />

your chance of being hit are 90%<br />

greater than they are in daylight.<br />

Working accidents at night is<br />

just part of the job. <strong>No</strong>t much<br />

you can do about it, other than<br />

have your head on a swivel the<br />

entire time you’re out there.<br />

But when it comes to traffic<br />

stops on a busy highway, maybe<br />

moving the violator off to the<br />

frontage road is a better option<br />

and might just save your life.<br />

And finally, I say to the departments<br />

that require their night<br />

shift officers to make dozens<br />

of traffic stops. Is the revenue<br />

gained from a ticket worth your<br />

officers’ life? I think not.<br />

6 The BLUES The BLUES 7