You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

14 — Vanguard, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 15, 2022<br />

Apprehension as S’Court sets to review<br />

powers of NJC to discipline judges<br />

Continues from Page 13<br />

the National level had changed<br />

hands from Dr Goodluck Ebele<br />

Jonathan to President Muhammadu<br />

Buhari who was touted as a<br />

no-nonsense Army General with<br />

zero-tolerance for corruption and<br />

injustice.<br />

Why I was sacked<br />

— Justice Olotu<br />

Sometime in October 2016, the<br />

sacked judge attempted a political<br />

solution to her case as she<br />

wrote a 13-page letter to President<br />

Muhammadu Buhari, urging him<br />

to intervene in her case.<br />

In the letter, Justice Olotu told<br />

President Buhari that she was a<br />

victim of victimisation orchestrated<br />

by a former Chief Justice of<br />

Nigeria, Justice Aloma Muktar,<br />

who was working with some powerful<br />

figures in the judiciary.<br />

Mrs. Olotu stated that she was<br />

compulsorily retired by the<br />

former CJN in order to satisfy “the<br />

wicked agenda of some judicial<br />

consultants” that wanted her to<br />

pervert the course of justice which<br />

she refused to do.<br />

According to the former judge,<br />

her ordeal started because she did<br />

not accede to the request of a<br />

former CJN, Justice SMA Belgore,<br />

and Chief Gabriel Osawaru<br />

Igbinedion to pervert the course<br />

of justice in some cases involving<br />

a widow and her children in suit<br />

No. FHC/UUY/CS/250/2003 and<br />

a case involving Mrs. Mona<br />

Youssefian and three others vs. Elf<br />

Petroleum Nigeria Limited.<br />

She added that in the suit filed<br />

before a Federal High Court in<br />

Uyo, the widow and her children<br />

sought redress over alleged negligence<br />

that led to the death of their<br />

husband and father on board a<br />

hotel vessel operated by the defendants.<br />

Mrs. Olotu stated that she gave<br />

judgment in favour of the family,<br />

which they sought to enforce in<br />

garnishee proceedings filed in the<br />

Port Harcourt Division of the Federal<br />

High Court.<br />

According to the petitioner, the<br />

judicial consultants, acting on<br />

behalf of Elf Petroleum and other<br />

defendants wanted her to vacate<br />

the garnishee order she made but<br />

she refused.<br />

“When I refused to do so, I incurred<br />

their wrath. This is my real<br />

offence and not any other picture<br />

Justice Aloma painted to the<br />

world,” Mrs. Olotu said.<br />

She added that the former CJN<br />

unconstitutionally used the instrumentality<br />

of her offices as CJN<br />

and Chairman of the NJC to further<br />

the vendetta of the judiciary<br />

consultants.<br />

Mrs. Olotu further alleged that<br />

the immediate past Attorney-<br />

General of the Federation, Mohammed<br />

Bello Adoke, was also<br />

conscripted into the conspiracy by<br />

misleading President Jonathan<br />

into approving the recommendation<br />

for her compulsory retirement,<br />

stating that the former CJN<br />

also withheld several material<br />

facts including her entire defense<br />

to the petition written against her.<br />

She went further to say that her<br />

retirement contravened several<br />

constitutional provisions, particularly<br />

Section 36 on fair hearing,<br />

adding that she wrote several letters<br />

to former President Jonathan<br />

but to no avail.<br />

The former judge urged President<br />

Buhari to “please pay attention<br />

to (her) relentless cry for truth<br />

and justice.”<br />

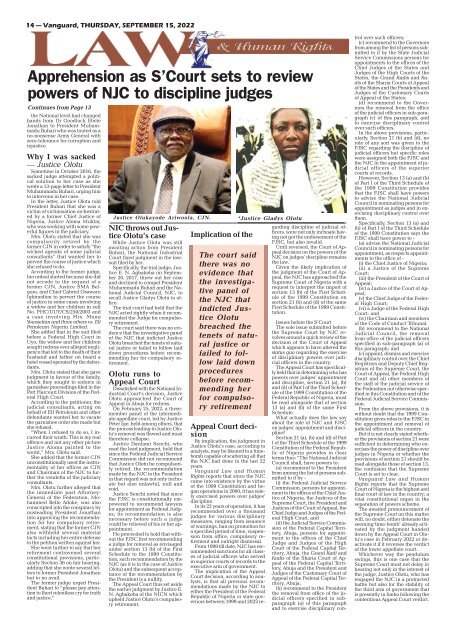

Justice Olukayode Ariwoola, CJN.<br />

NIC throws out Justice<br />

Olotu’s case<br />

While Justice Olotu was still<br />

awaiting action from President<br />

Buhari, the National Industrial<br />

Court fixed judgment in the lawsuit<br />

filed by her.<br />

Specifically, the trial judge, Justice<br />

E. N. Agbakoba on September<br />

20, 2017, threw out her case<br />

and declined to compel President<br />

Muhammadu Buhari and the National<br />

Judicial Council, NJC, to<br />

recall Justice Gladys Olotu to office.<br />

The trial court had held that the<br />

NJC acted rightly when it recommended<br />

the Judge for compulsory<br />

retirement.<br />

The court said there was no evidence<br />

that the investigative panel<br />

of the NJC that indicted Justice<br />

Olotu breached the tenets of natural<br />

justice or failed to follow laid<br />

down procedures before recommending<br />

her for compulsory retirement.<br />

Olotu runs to<br />

Appeal Court<br />

Dissatisfied with the National Industrial<br />

Court’s decision, Justice<br />

Olotu approached the Court of<br />

Appeal in Abuja for redress.<br />

On February 25, 2022, a threemember<br />

panel of the intermediate<br />

appellate court, led by Justice<br />

Peter Ige, held among others, that<br />

the process leading to Justice Olotu’s<br />

removal was flawed and must<br />

therefore collapse.<br />

Justice Danlami Senchi, who<br />

read the lead judgment, held that<br />

since the Federal Judicial Service<br />

Commission did not recommend<br />

that Justice Olotu be compulsorily<br />

retired, the recommendation<br />

made by the NJC to the President<br />

in that regard was not only inchoate<br />

but also unlawful, null and<br />

void.<br />

Justice Senchi noted that since<br />

the FJSC is constitutionally empowered<br />

to recommend lawyers<br />

for appointment as Federal Judges,<br />

its recommendation is also<br />

necessary before such a judge<br />

could be relieved of his or her appointment.<br />

He proceeded to hold that without<br />

the FJSC first recommending<br />

a judge for removal as envisaged<br />

under section 13 (b) of the First<br />

Schedule to the 1999 Constitution,<br />

such recommendation by the<br />

NJC (as it is in the case of Justice<br />

Olotu) and the subsequent acceptance<br />

of the recommendation by<br />

the President is a nullity.<br />

The Appeal Court thus set aside<br />

the earlier judgment by Justice E.<br />

N. Agbakoba of the NICN which<br />

upheld Justice Olutu’s compulsory<br />

retirement.<br />

Implication of the<br />

The court said<br />

there was no<br />

evidence that<br />

the investigative<br />

panel of<br />

the NJC that<br />

indicted Justice<br />

Olotu<br />

breached the<br />

tenets of natural<br />

justice or<br />

failed to follow<br />

laid down<br />

procedures<br />

before recommending<br />

her<br />

for compulsory<br />

retirement<br />

Appeal Court decision<br />

By implication, the judgment in<br />

Justice Olotu’s case, according to<br />

analysts, may be likened to a timebomb<br />

capable of scattering all that<br />

the NJC had done in the last 22<br />

years.<br />

Vanguard Law and Human<br />

Rights reports that since the NJC<br />

came into existence by the virtue<br />

of the 1999 Constitution and began<br />

operations in 2000, it has solely<br />

exercised powers over judges’<br />

discipline.<br />

In its 22 years of operation, it has<br />

recommended over a thousand<br />

judges for various disciplinary<br />

measures, ranging from issuance<br />

of warnings, ban on promotion for<br />

a specified period of time, suspension<br />

from office, compulsory retirement<br />

and outright dismissal.<br />

From 1999 till date, NJC has recommended<br />

sanctions for all classes<br />

of judicial officers who served<br />

in superior courts of records to the<br />

executive arm of government.<br />

The implication of the Appeal<br />

Court decision, according to analysts,<br />

is that all previous recommendations<br />

made by the NJC to<br />

either the President of the Federal<br />

Republic of Nigeria or state governors<br />

between 1999 and 2022 re-<br />

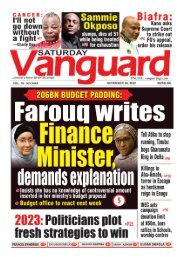

*Justice Gladys Olotu<br />

garding discipline of judicial officers,<br />

were not only inchoate having<br />

not got the endorsement of the<br />

FJSC, but also invalid.<br />

Until reversed, the Court of Appeal<br />

decision on the powers of the<br />

NJC on judges’ discipline remains<br />

the law.<br />

Given the likely implication of<br />

the judgment of the Court of Appeal,<br />

the NJC has approached the<br />

Supreme Court of Nigeria with a<br />

request to interpret the import of<br />

section 13 (b) of the First Schedule<br />

of the 1999 Constitution on<br />

section 21 (b) and (d) of the same<br />

First Schedule of the 1999 Constitution.<br />

Issues before the S’Court<br />

The sole issue submitted before<br />

the Supreme Court by NJC revolves<br />

around a quick review of the<br />

decision of the Court of Appeal<br />

which appears to have altered the<br />

status quo regarding the exercise<br />

of disciplinary powers over judicial<br />

officers in the country.<br />

The Appeal Court has specifically<br />

held that in determining who has<br />

powers over judges’ appointment<br />

and discipline, section 21 (a), (b)<br />

and (d) of Part I of the Third Schedule<br />

of the 1999 Constitution of the<br />

Federal Republic of Nigeria, must<br />

be read alongside that of section<br />

13 (a) and (b) of the same First<br />

Schedule.<br />

What actually does the law say<br />

about the role of NJC and FJSC<br />

on judges’ appointment and discipline?<br />

Section 21 (a), (b) and (d) of Part<br />

I of the Third Schedule of the 1999<br />

Constitution of the Federal Republic<br />

of Nigeria provides in clear<br />

terms thus: “The National Judicial<br />

Council shall, have powers to:<br />

(a) recommend to the President<br />

from among the list of persons submitted<br />

to it by -<br />

(i) the Federal Judicial Service<br />

Commission, persons for appointment<br />

to the offices of the Chief Justice<br />

of Nigeria, the Justices of the<br />

Supreme Court, the President and<br />

Justices of the Court of Appeal, the<br />

Chief Judge and Judges of the Federal<br />

High Court, and<br />

(ii) the Judicial Service Commission<br />

of the Federal Capital Territory,<br />

Abuja, persons for appointment<br />

to the offices of the Chief<br />

Judge and Judges of the High<br />

Court of the Federal Capital Territory,<br />

Abuja, the Grand Kadi and<br />

Kadis of the Sharia Court of Appeal<br />

of the Federal Capital Territory,<br />

Abuja and the President and<br />

Judges of the Customary Court of<br />

Appeal of the Federal Capital Territory,<br />

Abuja;<br />

(b) recommend to the President<br />

the removal from office of the judicial<br />

officers specified in subparagraph<br />

(a) of this paragraph<br />

and to exercise disciplinary control<br />

over such officers;<br />

(c) recommend to the Governors<br />

from among the list of persons submitted<br />

to it by the State Judicial<br />

Service Commissions persons for<br />

appointments to the offices of the<br />

Chief Judges of the States and<br />

Judges of the High Courts of the<br />

States, the Grand Kadis and Kadis<br />

of the Sharia Courts of Appeal<br />

of the States and the Presidents and<br />

Judges of the Customary Courts<br />

of Appeal of the States;<br />

(d) recommend to the Governors<br />

the removal from the office<br />

of the judicial officers in sub-paragraph<br />

(c) of this paragraph, and<br />

to exercise disciplinary control<br />

over such officers.<br />

In the above provisions, particularly,<br />

Section 21 (b) and (d), no<br />

role of any sort was given to the<br />

FJSC regarding the discipline of<br />

judicial officers but specific roles<br />

were assigned both the FJSC and<br />

the NJC in the appointment of judicial<br />

officers of the superior<br />

courts of records.<br />

However, Section 13 (a) and (b)<br />

of Part I of the Third Schedule of<br />

the 1999 Constitution provides<br />

that the FJSC shall have powers<br />

to advise the National Judicial<br />

Council in nominating persons for<br />

appointment as judges and in exercising<br />

disciplinary control over<br />

them.<br />

Specifically, Section 13 (a) and<br />

(b) of Part I of the Third Schedule<br />

of the 1999 Constitution says the<br />

FJSC shall have power to -<br />

(a) advise the National Judicial<br />

Council in nominating persons for<br />

appointment, as respects appointments<br />

to the office of -<br />

(i) the Chief Justice of Nigeria;<br />

(ii) a Justice of the Supreme<br />

Court;<br />

(iii) the President of the Court of<br />

Appeal;<br />

(iv) a Justice of the Court of Appeal;<br />

(v) the Chief Judge of the Federal<br />

High Court;<br />

(vi) a Judge of the Federal High<br />

Court; and<br />

(iv) the Chairman and members<br />

of the Code of Conduct Tribunal.<br />

(b) recommend to the National<br />

Judicial Council, the removal<br />

from office of the judicial officers<br />

specified in sub-paragraph (a) of<br />

this paragraph; and<br />

(c) appoint, dismiss and exercise<br />

disciplinary control over the Chief<br />

Registrars and Deputy Chief Registrars<br />

of the Supreme Court, the<br />

Court of Appeal, the Federal High<br />

Court and all other members of<br />

the staff of the judicial service of<br />

the Federation not otherwise specified<br />

in this Constitution and of the<br />

Federal Judicial Service Commission.<br />

From the above provisions, it is<br />

without doubt that the 1999 Constitution<br />

gives roles to the FJSC in<br />

the appointment and removal of<br />

judicial officers in the country.<br />

But it is not clearly stated whether<br />

the provisions of section 21 were<br />

sufficient in determining who exercises<br />

the power of discipline over<br />

judges in Nigeria or whether the<br />

provisions of section 21 should be<br />

read alongside those of section 13,<br />

the confusion that the Supreme<br />

Court is set to clear.<br />

Vanguard Law and Human<br />

Rights reports that the Supreme<br />

Court of Nigeria is the highest and<br />

final court of law in the country; a<br />

vital constitutional organ in the<br />

separation of powers scheme.<br />

The awaited pronouncement of<br />

the Supreme Court on this matter<br />

will, no doubt, either detonate the<br />

seeming‘time-bomb’ already activated<br />

by the judgment handed<br />

down by the Appeal Court in Olotu’s<br />

case in February 2022 or deactivate<br />

it if it reverses the verdict<br />

of the lower appellate court.<br />

Whichever way the pendulum<br />

swings, this is one case that the<br />

Supreme Court must not delay in<br />

hearing not only in the interest of<br />

the judge, Justice Olotu, who has<br />

engaged the NJC in a protracted<br />

battle but also for the stability of<br />

the third arm of government that<br />

is presently in limbo following the<br />

contentious Appeal Court verdict.