Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

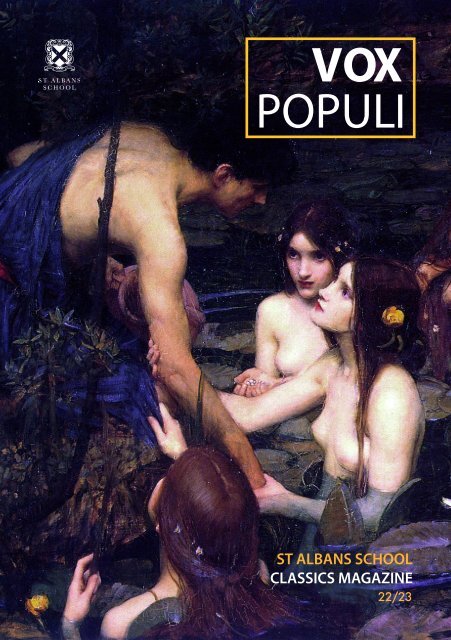

VOX<br />

POPULI<br />

ST ALBANS SCHOOL<br />

CLASSICS MAGAZINE<br />

22/23

Contents<br />

5 Editoral<br />

6 The Twelve Tables<br />

9 Ancient Medicine<br />

10 Cleopatra<br />

11 Gladiators<br />

12 Solon<br />

15 Women in Greek Mythology<br />

16 British Museum<br />

17 Roman Legal Procedure<br />

19 Xenophanes<br />

21 Composing Epic Poetry<br />

22 The Art of the Simile<br />

23 The Gallery<br />

24 Capital Punishment<br />

26 Moot Trial of Alexander the Great<br />

28 Life of Cicero<br />

30 Philology<br />

32 Dido<br />

2 3

Editorial<br />

Jonathan, Lower Sixth<br />

Our theme for this edition of vox<br />

populi is ‘panem et circenses,’<br />

the concept of ‘bread and<br />

games’ for the people, to<br />

reflect our desire to provide something for<br />

everyone’s taste in our magazine through<br />

its variety and depth of scholarship.<br />

As the field of Classics develops, so its<br />

boundaries widen to become ever more<br />

diverse in its scope. With that in mind,<br />

we have maintained our commitment to<br />

some of the more traditional philological<br />

aspects of the subject, but we have also<br />

considered how Classics is furthering the<br />

way it defines itself, spatially, temporally<br />

and at points of connectivity with other<br />

related academic disciplines and cultures<br />

as we look to the future. After all, we are<br />

at our strongest when we work together.<br />

The Classics Department and the<br />

Hylocomian Society have enjoyed a<br />

wealth of co-curricular experiences<br />

this year. Lower School students have<br />

visited part of the furthest reaches of the<br />

Roman Empire with their expedition to<br />

Hadrian’s Wall. As we have developed<br />

our scholarship beyond the curriculum,<br />

our Hylocomian Society lectures have<br />

been stimulating and challenging,<br />

considering questions from the nature<br />

of God to the very roots of Greek, Latin<br />

and our own languages. Enhancing our<br />

specialist knowledge further through<br />

the Sixth Form’s regular Symposium,<br />

students have collaborated on themes<br />

which stretch from archaic Greek history<br />

to later portrayals of one of the most<br />

powerful women in literature, Dido,<br />

Queen of Carthage. We are delighted to<br />

share our explorations with you.<br />

It only remains for me to thank all<br />

those involved in the production of this<br />

issue of vox populi. First, I would like<br />

to thank all the students and staff who<br />

have contributed articles and those who<br />

have kept us all thinking and reflecting<br />

on the ancient world through their<br />

enthusiasm and curiosity. The questions<br />

we have been asked on our Classical<br />

journey have resulted in more interesting<br />

answers. Second, thanks must be offered<br />

to my fellow student editors in the<br />

Lower Sixth Form, whose perspectives<br />

and contributions have been greatly<br />

appreciated. Finally, I would like to extend<br />

special thanks to Mrs Ginsburg, Head of<br />

Classics, for her tireless enthusiasm and<br />

support in developing this publication;<br />

her guidance and expertise have proved<br />

invaluable to us all.<br />

Opposite: The Romans of the Decadence - Thomas Couture<br />

4 5

The Twelve Tables<br />

Xavi, Lower Sixth<br />

After the last king of Rome had<br />

been expelled from Rome, the<br />

new republic was governed by<br />

a system of hierarchy between<br />

magistrates. However, only those who<br />

were part of the patrician class – an early<br />

Roman aristocracy comprised of ruling<br />

class families – were able to become<br />

magistrates. This was among other<br />

factors that led to great dissatisfaction<br />

amidst the plebian class who felt that<br />

they were unrepresented and at risk of<br />

being subject to tyranny of a higher class<br />

who had complete control of the law and<br />

its interpretation. This social struggle<br />

between classes is called the Conflict of<br />

the Orders and lasted roughly 200 years;<br />

the plebians effectively held the upper<br />

hand within the struggle as they could<br />

hold Rome ‘hostage’ by threatening to<br />

leave the city so that it would come to a<br />

standstill because the plebians were the<br />

city’s labour force. The Twelve Tables<br />

are a consequence of plebians insisting<br />

that the previously unwritten customs<br />

from which law in Rome was derived<br />

be codified. The Twelve Tables were not<br />

a reform but instead a way for regular<br />

Roman citizens, beyond the previous<br />

model which involved only a handful<br />

of specialised magistrates being familiar<br />

with the law, to know their rights as well<br />

as the Tables acting as a safeguard from<br />

tyranny.<br />

Following increased pressure from<br />

Roman plebians in the 450s BC, a<br />

committee called the ‘decemviri’ (literally<br />

translating After the last king of Rome<br />

had been expelled from Rome, the new<br />

republic was governed by a system of<br />

hierarchy between magistrates. However,<br />

only those who were part of the patrician<br />

class – an early Roman aristocracy<br />

comprised of ruling class families – were<br />

able to become magistrates. This was<br />

among other factors that led to great<br />

dissatisfaction amidst the plebian class<br />

who felt that they were unrepresented<br />

and at risk of being subject to tyranny of a<br />

higher class who had complete control of<br />

the law and its interpretation. This social<br />

struggle between classes is called the<br />

Conflict of the Orders and lasted roughly<br />

200 years; the plebians effectively held the<br />

upper hand within the struggle as they<br />

to ten men) was established and sent to<br />

Greece in order to study the legal system<br />

of Athens and other Greek civilisations.<br />

The first committee completed the first<br />

ten codes of the eventual twelve in 450BC<br />

and a year later a second committee of ten<br />

men completed two more codes after a<br />

‘secessio plebis’ (secession of the plebes)<br />

compelled the Senate to consider them.<br />

After the last two codes were finished –<br />

the twelve tables were finally declared<br />

law.<br />

The Twelve Tables was the first legal<br />

document codifying the rights that each<br />

and every Roman citizen had – these<br />

tables were comprised of ‘unwritten laws’<br />

that were already an established norm in<br />

Roman culture. The provisions set out<br />

by the Twelve Tables recognised legal<br />

conventions that are now commonplace<br />

in modern legal systems around the<br />

work; these included equal rights for all<br />

citizens to a fair trial by due process, laws<br />

surrounding slander and defamation,<br />

and differentiation between murder and<br />

manslaughter.<br />

The first three tables explore the rights of<br />

citizens concerning trials, due processes in<br />

court and how the judgement of the court<br />

could be exacted. The first table discusses<br />

proceedings between the plaintiff and<br />

defendant; it considers how the court<br />

should respond to various circumstances<br />

such as what to do if the defendant fails to<br />

appear in court or age/sickness prevents<br />

them from doing so. An unusual feature<br />

of this table for modern readers would<br />

be the principle that if either one of the<br />

parties failed to appear at the trial, then<br />

the judge would make their judgement<br />

in favour of the present party no matter<br />

the circumstances. This also formed a<br />

system of timetabling for the trial, as it<br />

was decreed that all trials would end at<br />

sunset. The second table talks further<br />

Above: Appius Claudius Caecus in Senate - Cesare Maccari<br />

about court proceedings – it states that if a<br />

witness failed to show up, then the party<br />

who summoned them could shout and<br />

scream in front of his house every three<br />

days. This table also states that a slave<br />

who committed theft should be flogged<br />

and then thrown to their death off of the<br />

Capitoline Hill cliff.<br />

The third table is most notable for dictating<br />

how to deal with defrauding and areas<br />

surrounding credit. Table III declares that<br />

after 30 days of the debt being unpaid,<br />

then the debtor would be brought to court<br />

by force and the court would then hand<br />

the debtor to the creditor for a period of<br />

up to 60 days, which would most likely<br />

be for labour. The conditions on which<br />

the debtor should be held are also set out<br />

and after the term of 60 days, the debtor<br />

could in some circumstances be sold into<br />

slavery.<br />

The fourth table sets out the rights of<br />

the ‘paterfamilias’ (the patriarch of the<br />

family) which specifically apply to him.<br />

This part of the code contains disturbing<br />

proclamations such as that “dreadfully<br />

deformed” children should be quickly<br />

euthanised by the father and that if a<br />

father tries to sell his son three times, then<br />

the son will automatically become free.<br />

This section also dictates that sons are<br />

born into the inheritance of their family<br />

and that if a boy is born within 10 months<br />

of their suspected father’s death then they<br />

are entitled to the man’s inheritance.<br />

Tables V, VI and X discuss estates,<br />

possession and religion and therefore<br />

largely pertain to women as women at<br />

the time were seen as possessions, which<br />

is evident from the laws surrounding<br />

ownership. Table five is concerned with<br />

guardianship and the wills of citizens;<br />

any inheritance was automatically given<br />

to a man’s sons, however, if he had no<br />

6 7

sons then it would be given to his nearest<br />

male relative. However, if the man had<br />

no living male relatives, members of his<br />

extended family would become the heirs<br />

to the inheritance. Women were also<br />

forced to remain under the guardianship<br />

of a man, whether it was their husband<br />

or father, no matter how old they were<br />

(the notable exception to this were the<br />

Vestal Virgins. The sixth table states<br />

that a woman who lived with a man for<br />

one year was his by marriage – and to<br />

avoid this would have to be away from<br />

his house for three consecutive nights<br />

each year. This table also discusses the<br />

freedom of slaves and how to go about<br />

it – if there was an argument concerning<br />

two conflicting claims over a slave’s<br />

freedom, then the judge would have to<br />

rule in favour of freeing the slave if there<br />

was a lack of evidence. The tenth table –<br />

concerned with religion and rites – stated<br />

that women should not wail nor scratch<br />

their faces when they were mourning<br />

and that no more than three women<br />

were permitted to prepare a corpse for a<br />

funeral. The manner in which cremations<br />

took place was also set out – jewellery<br />

was not allowed to be cremated and<br />

pyres could not be built from expensive,<br />

polished woods.<br />

Tables seven and eight cover areas of what<br />

modern legal systems would call tort<br />

law, as well as covering land rights. The<br />

seventh table declared that all roads were<br />

to be eight feet wide and that the people<br />

who live near it were responsible for its<br />

upkeep. Table VIII sets the precedent that<br />

one who causes another damage should<br />

pay the victim double the value of the<br />

damaged property – if the perpetrator<br />

was a child, then the victim could decide<br />

whether or not to flog them. The most<br />

startling convention set out in this section<br />

was a death penalty for slander – the<br />

guilty party was to be put to death by<br />

clubbing.<br />

The eight table also deals with the crime<br />

of killing, intentional and unintentional,<br />

and the circumstances of the specific<br />

murder who determine what punishment<br />

was to be given (patricide, for example,<br />

was treated differently to homicide). The<br />

penalty for accidentally causing one’s<br />

death was to appease the victim’s family<br />

by offering a ram for a public sacrifice.<br />

Murder was obviously punishable by<br />

death; yet patricide was viewed as the<br />

worst possible crime. Someone found<br />

guilty of patricide was to be sewn into a<br />

leather sack containing a dog, a viper, and<br />

a cockerel and then flung into a river.<br />

Table IX sets out the concept adopted by<br />

countries around the world that everyone<br />

is equal in the eyes of the law. This table<br />

also decrees that death sentences were<br />

only allowed to be given by a court of<br />

law and these verdicts could be appeal in<br />

some cases.<br />

The last two tables (XI & XII)<br />

supplemented the other ten tables –<br />

however the eleventh table that forbid<br />

marriage between the plebeian and<br />

patrician classes was repealed shortly<br />

after being introduced. The twelfth and<br />

final table clarifies certain aspects of the<br />

other tables – it sets out a distinguishment<br />

between intentional and accidental<br />

killing.<br />

Ancient Medicine<br />

Subechya, Lower Sixth<br />

The ancient world believed that the gods<br />

were the reason why they got sick, as<br />

they were often held responsible for good<br />

health. The ancients believed that if they<br />

angered the gods this could cause them to<br />

fall ill.<br />

Above: The Temple of Asclepius at Villa Borghese in Rome -<br />

Anonymous<br />

The earliest doctor is claimed to be<br />

Asclepius; yet, many question whether<br />

he truly even existed. Many did however<br />

believe in his existence due to his Temple<br />

in Rome and Sanctuary at Epidauras<br />

where ‘no patient ever died’, this being<br />

because anyone on the verge of death<br />

was denied admittance and existing<br />

patients with worsening conditions were<br />

abandoned in the forest by priests.<br />

Matters changed with the arrival of<br />

Hippocrates, the first to discredit that<br />

the magical cures and promote belief<br />

in the study of the human body and<br />

experimental research.<br />

8 9<br />

Some ancient medical practices include<br />

trepanning, use of animal dung as a<br />

beauty balm and as an elixir of human<br />

flesh, bone and blood to cure headaches,<br />

as well as muscle cramps and stomach<br />

ulcers.<br />

Women were not spared from the<br />

patriarchal society, even with regards to<br />

medicine and because they were viewed<br />

as filth, they thought that there was no<br />

other suitable cure for them other than<br />

filth.<br />

Despite this, the main cure for the most<br />

common ailments experienced by women<br />

was thought to be sex and pregnancy.<br />

They believed that when a woman did<br />

not have intercourse, her womb became<br />

dry and was liable to become displaced,<br />

a condition known as hysteria (from the<br />

Greek hystēr ‘womb’).<br />

Therefore, the ancient medical practice<br />

made some fatal errors, yet they have<br />

provided the basis for the principles<br />

which we have since developed.<br />

Above: Alexander of Macedon trust the doctor Philip - Henryk<br />

Siemiradski

Cleopatra<br />

Parth, Second Form<br />

My symposium was done on Cleopatra’s<br />

supposed suicide, and whether she did<br />

kill herself be getting her maids to sneak<br />

in a fig basket with a snake in. After all<br />

Octavian, being a typical Roman emperor,<br />

was a twisted psychopath, and if he did<br />

want to kill Cleopatra, he’d tell everyone<br />

it was suicide.<br />

After all, the snake that killed her was<br />

called an aspis, which, depending on the<br />

language, could mean a Saharan Sand<br />

Viper, or an Egyptian Cobra – the first has<br />

weak venom that can’t kill you, and the<br />

second is too big to be smuggled in in a fig<br />

basket, and the venom is only discharged<br />

50% of the time, and the maids committed<br />

suicide after Cleopatra (Or did they –<br />

maybe they were killed as witnesses)<br />

Talking about the fig basket – the biggest<br />

Egyptian baskets were not big enough to<br />

hold a snake. Trust me, I spent a full hour<br />

on the Le Louvre website trying to search<br />

up basket before realising it was a French<br />

website, and then I searched up French for<br />

basket, and all it gave me was the wrong<br />

thing. French for basket was panier!<br />

The Psylli were a tribe – now extinct – of<br />

nomads. The Romans claimed they can<br />

heal snakebites. That sounds plausible,<br />

right? The Romans also claimed they<br />

were immune to poison. Okay, maybe it<br />

could be true? They had no females. Still<br />

slightly plausible? They also went extinct<br />

600 years before Octavian lived.<br />

Whether the Psylli existed or not, Octavian<br />

said he marched in with the Psylli just<br />

after Cleopatra committed suicide –<br />

even though it would take 4-5 days to<br />

take them there, even on horseback! Did<br />

he know Cleopatra was going to die of<br />

poison.<br />

The snake was never found in the room.<br />

Also, how did the maids catch the asp?<br />

One major thing to consider is that<br />

the same way we have biases around<br />

countries, the Romans thought that Egypt<br />

was full of snakes, the same way we<br />

think all Italians eat pizzas (pizza is made<br />

mainly for tourists).<br />

Also, Egyptians think there is only<br />

one way to commit suicide without<br />

having yourself being eaten by Ammit<br />

the Devourer – to jump into the river<br />

Nile (which would turn you immortal).<br />

Romans, however, thought that suicide<br />

was a Roman way of death, so it would<br />

make sense to Octavian that Cleopatra<br />

would commit suicide, but not to the<br />

Egyptians!<br />

Gladiators<br />

Will, Third Form<br />

On the 16th of January, St Albans School<br />

was visited by author Ben Kane. One<br />

particularly interesting part of the<br />

workshop was the Roman Gladiator<br />

Fact or Myth Section where Ben Kane<br />

myth busted common myths regarding<br />

gladiators.<br />

Some surprising myths came up like the<br />

fact that all gladiators did not fight to<br />

the death. This rattled our perception of<br />

gladiatorial fights.<br />

We were also informed of the fact that<br />

gladiators were not terribly muscular.<br />

Many TV shows and movies portray<br />

gladiators to be muscular and fit but<br />

Opposite: The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra - Sir<br />

Lawrence Alma-Tadema<br />

Below: Ave Caesar! Morituri te salutant - Jean Léon Gérôme<br />

scientific evidence proves this to be false.<br />

Ben Kane explained to us that muscular<br />

people who got injured are more likely<br />

to be unable to fight since their skin is<br />

thin. More obese people could get cut<br />

and since their skin is thick they would<br />

not be properly injured. This led to the<br />

conclusion that more obese people could<br />

survive longer in gladiatorial games. This<br />

was fascinating to understand. Ben Kane<br />

showed us the bridge between history<br />

and science.<br />

Modern artwork does not accurately<br />

depict the true nature of gladiatorial<br />

games. One painting that the author<br />

showed us described a naval battle taking<br />

place in an arena. We were showed by<br />

Ben Kane that this is actually wrong. He<br />

explained that arenas could not hold that<br />

much water and that many ships due to<br />

its size.<br />

I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and<br />

hope to have many more.<br />

10 11

Solon: Reformer,<br />

Law Maker, Poet<br />

Jonathan, Lower Sixth<br />

The principal sources for<br />

details of Solon’s life are<br />

Herodotus and Plutarch,<br />

with Aristotle providing<br />

information on changes in<br />

the field of law.<br />

Who was Solon?<br />

Solon was an Athenian politician and poet<br />

of noble birth who lived in the late seventh<br />

and early sixth centuries BCE. One of the<br />

Seven Sages listed in Plato’s Protagoras,<br />

he was archon at Athens 594-593 BCE.<br />

This is probably when he put in place<br />

his reforms, which modernised Dracon’s<br />

earlier laws. Despite his noble birth, he<br />

came to sympathise with the poor. After<br />

his archonship, he left Athens to travel<br />

for 10 years, with this being the period<br />

of time within which the Athenians had<br />

agreed not to change his laws in order for<br />

them to have time to take effect.<br />

Why is Solon an important figure in<br />

ancient Greek history?<br />

Through his changes and legislation, Solon<br />

laid the foundations for the reasonably<br />

stable society of democratic Athens. His<br />

reforms strengthened the assembly and<br />

the law courts. Furthermore, he made<br />

changes to society which created a free<br />

peasant class and curbed the powers of<br />

the nobility to some extent. Indeed, he<br />

Below: Solon - Merry Joseph Blondel<br />

can be considered an early agent in social<br />

class struggle, if we wish to use a rather<br />

anachronistic term.<br />

Arguably, Solon’s most important reform<br />

was ‘seisachtheia’ (literally a ‘shaking off<br />

of burdens’), which is sometimes seen as<br />

a cancellation of debts. It is more likely<br />

to have been a liberation of the class of<br />

‘hektemeroi’ (sixth parters) who gave<br />

a sixth of their produce to an overlord.<br />

This was abolished and they became<br />

absolute owners of their land. However,<br />

Solon did introduce changes to limit the<br />

social impact of debt. Specifically, men<br />

enslaved for debt were freed and it was<br />

no longer legal to enslave someone on<br />

these grounds.<br />

The commercial environment at Athens<br />

the commercial growth of olives for trade.<br />

This reform also yielded social benefits<br />

since it kept an affordable food supply at<br />

home.<br />

How did he organise the Athenian<br />

citizens and what was the political<br />

impact?<br />

Solon categorised the people of Athens into<br />

four property classes, which undermined<br />

the power of noble families where political<br />

influence was hereditary. The four classes<br />

were the Pentakosiomedimoi (who<br />

owned property to yield 500 medimnoi<br />

at least), the Hippeis (generally cavalry<br />

when required), the Zeugetai (whose<br />

land yielded 200-300 medimnoi)and the<br />

Thetes (lowest of four property classes).<br />

The two higher classes held the major<br />

political offices while the zeugetai<br />

were eligible for minor offices. Thetes<br />

were permitted to attend the assembly<br />

(ekklesia) and the law court (Eliaia). It<br />

is also possible that Solon incorporated<br />

allotment to the election of archons and<br />

he probably created a new council of 400<br />

to prepare business for the assembly.<br />

What was the nature of Solon’s<br />

legislation?<br />

The evidence we have for Solon’s<br />

legislation suggests an emphasis on<br />

social cohesion. In the area of family law,<br />

orphaned heiresses did not enter their<br />

husband’s family but were to produce<br />

heirs for their own family, and those who<br />

did not have heirs were able to adopt a man<br />

to be heir under certain conditions. There<br />

was a moral element to the legislation<br />

since there were punishments for a lack<br />

of chastity in women, as there were for<br />

the procurement and prostitution of<br />

boys, and a further law against excessive<br />

display at funerals. Moreover, theft was<br />

harshly punished if in the dark or from a<br />

public place such as a market.<br />

What do we know about Solon as a poet?<br />

Unfortunately, Solon’s poetry only exists<br />

in fragments. It appears to be focused on<br />

his reforms and is rather moralising in<br />

tone. Examples include:<br />

Laws I wrote alike for nobleman and<br />

commoner, awarding straight justice to<br />

everybody. (24.18)<br />

To the demos I have given such honour as<br />

seems sufficient, neither taking away nor<br />

granting them more. For those who had<br />

power and were great in riches, I equally<br />

cared that they should suffer nothing<br />

wrong. Thus, I stood holding my strong<br />

shield over both, and I did not allow<br />

either to prevail against justice. (5.1ff)<br />

(Translation by Eherenberg)<br />

What does Herodotus tell us about him?<br />

The fifth century (BCE) historian,<br />

Herodotus, tells us that, during his ten<br />

years of travelling after implementing his<br />

reforms, Solon arrived in Sardis, the major<br />

city of Lydia, where he met King Croesus.<br />

Croesus asked him whom he considered<br />

to the happiest of men, to which Solon<br />

replied an Athenian called Tellus, who<br />

had sons, all of whom had surviving<br />

children. Tellus fought for Athens, died<br />

in battle and had a glorious death. As a<br />

result, he was honoured with a public<br />

funeral. Solon would not even agree<br />

that Croesus was the second happiest<br />

person, instead citing two Argive young<br />

men who dragged their mother’s cart to<br />

12 13

Women in Greek Mythology<br />

Izzy, Lower Sixth<br />

Medusa was a woman who<br />

had snakes instead of hair<br />

and turned men to stone<br />

when they looked her in<br />

the eye. She lived in a cave with her two<br />

sisters, Stheno and Euryale, and they<br />

were collectively known as the Gorgons.<br />

Many people over time have villainised<br />

Medusa and turned her into a monster<br />

when, in reality, she was mostly innocent.<br />

nobody labels him as evil or twisted.<br />

I also talked about other women such<br />

as Medea, the witch queen of Corinth,<br />

Pandora, the first mortal woman, and<br />

Circe, the sorceress of Aeaea, who I feel<br />

are similarly unjustly represented in<br />

Greek mythology.<br />

Hera’s temple, ensuring their reputation,<br />

then died peacefully in the temple. His<br />

point was that no man can be considered<br />

happy until he is dead since he does not<br />

know what lies ahead. Croesus only<br />

understood the wisdom of Solon’s words<br />

when he had lost his kingdom to the King<br />

of Persia, Cyrus, and was imprisoned.<br />

HOW SHOULD WE EVALUATE SOLON?<br />

Was Solon a revolutionary?<br />

The evidence suggests that he was an<br />

agent of class change but not radical.<br />

Did his changes last?<br />

They were broadly sustained. His laws<br />

were lasting but social factionalism broke<br />

out. Some Athenians blamed Solon for not<br />

becoming a tyrant and, in fact, Peisistratus<br />

later became a tyrant at Athens.<br />

What was his legacy?<br />

His most significant contribution to the<br />

development of Athenian politics was<br />

that he paved the way for Cleisthenes’<br />

democratic reforms at Athens in the<br />

later sixth century BCE. And, of course,<br />

even then, women and slaves were still<br />

excluded from political power.<br />

Above: Croesus and Solon<br />

Medusa was born a very beautiful human,<br />

so beautiful that the god Poseidon took<br />

interest in her, resulting in him forcing<br />

himself on her inside Athena’s temple<br />

where Medusa ran hoping for protection<br />

from the goddess. From this event,<br />

Athena cursed Medusa turning her hair<br />

into snakes so she was no longer attractive<br />

and cursing her sight so she could never<br />

be with a man again. It has been argued,<br />

however, that this was done so nobody<br />

could take advantage of her again and<br />

Athena was giving her a way to protect<br />

herself.<br />

People also make her out to be a coldhearted<br />

beast because she turns men into<br />

stone, however, she did more damage in<br />

death than in life as there are little to no<br />

tales of her maliciously turning people<br />

to stone yet her decapitated head was<br />

Perseus’ favourite weapon. Her face was<br />

even put on the Aegis which was a shield<br />

Athena carried in battle.<br />

Medusa is also unfairly portrayed partly<br />

down to her gender as there are other<br />

examples of characters such as Midas<br />

who, at his request, was “blessed” with<br />

the gift of turning objects into gold but<br />

Below: Perseus, under the protection_of_Minerva, turns<br />

Phineus to stone by brandishing the head of Medusa<br />

14 15

British Museum<br />

Johan, Third Form<br />

Roman Legal Procedure<br />

Xavi, Lower Sixth<br />

On Monday 6th January, the classics<br />

department and students went on a trip,<br />

visiting the British Museum. Upon arrival,<br />

we first got to explore the fascinating<br />

hieroglyphics exhibition, featuring the<br />

world-famous Rosetta Stone. The Rosetta<br />

Stone was a relatively insignificant<br />

proclamation from King Ptolemy V, but<br />

was inscribed in 3 different languages,<br />

demotic, hieroglyphic and Greek<br />

allowing experts to translate demotic<br />

and hieroglyphic. It was very interesting<br />

to learn about the history of the Rosetta<br />

Stone and how it made its way from<br />

Egypt to the British Museum after being<br />

discovered by the French. We got to see<br />

the wide variety of different hieroglyphics<br />

and how they could form new words in<br />

different combinations. There are in total<br />

over 700 hieroglyphics, many of which<br />

were difficult to tell apart, making it a<br />

very difficult language to decipher.<br />

There were also lots of Egyptian statues to<br />

see, which were impressively carved out<br />

of stone. Many of them were Sphynxes<br />

with lion’s hindquarters. Afterwards,<br />

we were able to explore the museum<br />

independently, which allowed us to<br />

explore our own historical interests. I<br />

personally really enjoyed visiting the<br />

medicine display that explores the<br />

thousands of drugs and pills that an<br />

average British person takes in a lifetime.<br />

I was shocked to find out how many<br />

pills people on average end up taking<br />

throughout their lives. This exhibition<br />

also provides a fascinating opportunity<br />

to appreciate the wonders of modern<br />

medicine that have so greatly improved<br />

our lives. Finally, we had time to browse<br />

the gift shop in order to find things with<br />

which to remember our trip by.<br />

Below: The Sphinx<br />

The legal procedure that Rome<br />

used in its courts evolved<br />

throughout the lifetime of the<br />

Republic and then Empire; the<br />

foundations that the Romans laid for<br />

legal method have been used as the base<br />

for the legal systems for the majority of<br />

European countries and others around<br />

the world. The development of the<br />

system was shaped by three major events:<br />

the ‘legis actiones’, the ‘formulary system’<br />

and the ‘cognitio extraordinaria’ which<br />

was in use after the fall of Rome.<br />

The ’legis actiones’ were formulated<br />

around the same time as the Twelves<br />

Tables of Roman law in the fifth century<br />

BC – these acts divided the court<br />

proceedings into several steps. A plaintiff<br />

would first have to address the defendant<br />

in a public forum and request them to<br />

go to court; however, if the defendant<br />

refused to go to court, they would be<br />

taken there by force. Each case that was<br />

taken to court was separated into two<br />

parts, the first of which was primarily<br />

a formality where a magistrate would<br />

decide whether there was a good case for<br />

a trial and, if there was, they would set out<br />

the specifics of the issue. Once the issues<br />

at hand had been defined, a ‘iudex’ who<br />

was a sort of legal layman as opposed to<br />

a barrister or magistrate would be chosen<br />

by both the plaintiff and defendant. The<br />

second part of the trial would happen<br />

under the supervision of this iudex,<br />

this stage was less formal than the first<br />

and it was here that witnesses would be<br />

called to the stand, evidence set out and<br />

barristers would make their arguments.<br />

However, the verdict that the iudex came<br />

to was simply advisory and they did not<br />

have the power to execute the decision;<br />

unlike modern judicial systems, the party<br />

which won the trial was responsible for<br />

enforcing the judge’s verdict themselves.<br />

If the losing party refused to pay the<br />

penalty, then the court was allowed<br />

to bring them back by force and pay a<br />

heftier penalty. This heightened penalty<br />

depended on the nature of the original<br />

trial – if the case involved debt, then the<br />

debtor’s assets could seized or they could<br />

be given as a slave to the plaintiff until<br />

the debt was paid off. The alternative was<br />

to sell them into slavery or to have them<br />

dismembered.<br />

As Roman society evolved, the cases that<br />

came to the courts grew more complex<br />

and in turn the judicial system advanced.<br />

The new formulary system was created to<br />

replace the overly formal and traditional<br />

‘legis actionis’ system; its roots were<br />

found in the way in which praetors dealt<br />

with foreigners, but it was deemed so<br />

effective that its use was adopted into<br />

regular Roman law. These reforms meant<br />

that the process was more streamlined as<br />

well as the proceedings now being written<br />

down. The pre-existing custom of calling<br />

the defendant to court remained, but now<br />

the plaintiff could physically drag the<br />

defendant to court. The formulary system<br />

got its name from the formula used in<br />

the preliminary hearing comprised of six<br />

stages: nominatio, intentio, condemnatio,<br />

demonstratio, exceptio, and praescriptio.<br />

The main difference between trials under<br />

the formulary system and those of modern<br />

16 17

systems is that the case could occasionally<br />

be resolved in the preliminary hearing via<br />

the taking of oaths. Taking an oath to the<br />

gods was seen as a deeply serious matter<br />

and very few people would be willing to<br />

perjure themselves (the penalty for perjury<br />

was grave in both the eyes of the law<br />

and the gods). The plaintiff could throw<br />

the gauntlet to the defendant by making<br />

him swear an oath – if the defendant was<br />

willing to take this oath, then he won, but<br />

if he did not, then he lost. This could be<br />

reversed for the plaintiff where the same<br />

rules would apply.<br />

If the trial progressed beyond the<br />

preliminary hearing, it would play out in<br />

the same way as under the ‘legis actionis’<br />

system. In the case of the debt, a new<br />

procedure of holding a public auction<br />

of the possessions of the debtor’s estate<br />

would help the creditor to be reimbursed.<br />

The third and final major development<br />

in the procedure of the Roman judicial<br />

process was the introduction of the<br />

‘cognitio extraordinaria’ system. This<br />

system was introduced after the Roman<br />

Empire succeeded the Republic and bears<br />

the most similarity with modern justice<br />

structures. For the first time, defendants<br />

were summoned to the court by the court<br />

instead of the plaintiff having to summon<br />

them; plaintiffs had to file a statement of<br />

claim. If either one of the parties failed to<br />

show at court on the date three separate<br />

times then the party which turned up<br />

won by default. The other major change<br />

that the cognito system brought was the<br />

process of appeals – the case could in<br />

theory progress up through higher courts<br />

and potentially reach the emperor.<br />

Although law predates Rome by<br />

thousands of years through social<br />

convention and speech, Romans<br />

revolutionised the way in which the rule<br />

of law was implemented. It created a<br />

blueprint for the societies that followed<br />

through its systematic and impartial<br />

process; while none of the punishment<br />

have stood the test of time, the way in<br />

which the law is applied remains largely<br />

the same.<br />

Below: Roman Law<br />

Xenophanes<br />

Jonathan, Lower Sixth<br />

In the Autumn term Dr Shaul Tor, Senior<br />

Lecturer in Ancient Philosophy at King’s<br />

College London, delivered an insightful<br />

lecture on the philosophy of Xenophanes<br />

to the Hylocomian Society. His theme<br />

was: What if cows could draw Gods?<br />

And what do we see in a rainbow? Some<br />

philosophical questions in Xenophanes.<br />

Dr Tor began with an exploration of<br />

Xenophanes’ biography. The Presocratic<br />

philosopher was active in Colophon<br />

(in Ionia) at the end of the sixth and<br />

beginning of the fifth century BCE. He<br />

travelled widely around Greece and<br />

wrote in verse, using both the hexameter<br />

and elegiac form. Xenophanes’ interests<br />

lay in theology, knowledge and belief,<br />

natural philosophy, ethics and politics.<br />

His work remains either in fragmentary<br />

form or preserved in the works of other<br />

writers such as Aristotle and Plutarch.<br />

Dr Tor then proceeded to reveal how<br />

the fragmentary evidence we have for<br />

Xenophanes’ work can be worked into a<br />

coherent picture of his stated perspective<br />

on the nature of the gods. By way of<br />

context it is important to consider the<br />

fact that the ancient Greek literary canon<br />

drew heavily on Homer’s epics, The<br />

Iliad and The Odyssey, and Hesiod’s<br />

poetry about the origins of the gods,<br />

Theogony. Both writers feature multiple,<br />

anthropomorphic, imperfect deities.<br />

However, fragments of Xenophanes’<br />

work show him noting mortal belief that<br />

gods are born and have bodily form and<br />

clothing similar to their own.<br />

He further notes that the poets portray<br />

the gods as committing acts which are<br />

reprehensible for mortals, for example<br />

theft, adultery and deceit. Aristotle’s<br />

18 19<br />

capture of Xenophanes’ philosophy<br />

suggests that he considered it to be<br />

impious to suggest that gods came into<br />

being or die. Furthermore, Xenophanes’<br />

fragments draw out his suggestion that<br />

all people create god in their own image;<br />

he suggests that the Thracians and<br />

Ethiopians, who tend to look physically<br />

very different, say that their gods look<br />

like them and, if they could draw, horses<br />

would render images of their gods to look<br />

like horse and oxen to look like oxen.<br />

What is particularly interesting in the<br />

further fragments is the similarity<br />

of Xenophanes’ philosophy to a<br />

monotheistic system. Although his<br />

assertion of “One god, greatest among<br />

gods and men,” does not exclude<br />

polytheism, his assertion of this being<br />

as “not at all like mortals either in frame<br />

or cognition” implies an unknowable<br />

quality in a supreme god. Moreover,<br />

he also alludes to an omniscience and<br />

omnipotence in this supreme god. This<br />

being is further located as unchangeable<br />

in space and time. These fragments have<br />

remarkable resonance in modern religion.<br />

Xenophanes is no less critical of the minor<br />

deities, often deployed by ancient writers<br />

to explain natural phenomena. In a further<br />

fragment, he critiques the goddess Iris,<br />

who manifests as a rainbow, believing her<br />

to be “by nature cloud, purple, and red,<br />

and greenish-yellow to behold.” This is<br />

a marked step away from the Olympian<br />

pantheon and their attendant demi-gods<br />

and goddesses, who cause thunder,<br />

storms, and the changing of the seasons.<br />

In short, Dr Tor left us with the impression<br />

of a very modern mind forged in an<br />

ancient context and much to consider<br />

to explore further the philosophy of the<br />

Presocratics.

Composing Epic Poetry<br />

John-Ellis, Lower Sixth<br />

from ἡ Οὐλσινεία: Ulsinea (v. 136-150)<br />

σίγησεν δ’ αὖ Γαβριήλ· μᾶλλον δ’ ἀνά χεῖρας<br />

But Gabriel was silent in response; rather, he lifted up his hands<br />

κρούσεν ἄγων, παράδειγμα δ’ ἔτριψεν ἐς οὔτι οὗ ἧκεν.<br />

and clapped, and the paradigm crumbled into the naught whence it came.<br />

Γαβριήλ δὲ κρινοστέφανος στῆθος μεγαλαύχει<br />

And Gabriel of the lily garland began to boast his chest,<br />

δῖον ὁρᾶν· αὔξῃ ὠλενῶν πόδε γυμνώ ἀνεῖχον.<br />

godly to behold; with the expanse of his arms, his unshod feet began to arise.<br />

κρᾶτ’ ἀνέκυψε κόμην δ’ ἀγαπηθεῖσαν καθέηκεν<br />

He tilted back his head and let down his pampered hair<br />

λουθεῖσάν τ’ Ἐδὲμ ὑδρηλῇ ὑγρήν τε ἀλοιφῇ<br />

which had been bathed in watery Eden and was moist with ointment<br />

Σουμερίης τετραρειθρώδευς πολυχρύσου Εὐιλάτ.<br />

from Sumer of the four bounding streams and Havilah, rich in gold;<br />

ἠΰτε πέρ ῥεθομαλίδας οὔπω ὀπωρῃ ἔτ’ Εὔα<br />

just as when apple-cheeked Eve, still not yet in any way tainted by the fruit,<br />

κως μυσαρή, ἐκ Σόλλακος εἶσ’ ἐπί ἀνέρι καλή,<br />

cometh forth from the Sollax as a beauty for her husband,<br />

οἷ δὲ δίδωσιν ἔλαιον ἑκών μενοεικέσι χερσίν,<br />

and he willingly offers her olive oil with his agreeable hands,<br />

ὄφρα φέρῃ κτένα βωλοκόπον βλοσυρῆς διά χαίτης<br />

that she may lead her clod-breaking comb through her shaggy mane,<br />

ᾄσσομένης μελανοπλοκάμου λείῳ κατά νώτῳ.<br />

which flutters in black tresses down her smooth back.<br />

ἐσθλή ἐπόψει Εὔα ποιητῶ παντετοκυῖα,<br />

And Eve, mother of all, is good in the sight of her Maker,<br />

εὐώδης θρέμμασσιν, ἅ ἦρος ἀνεῖκε χίμαιρα·<br />

sweet to the smell of nurslings, whom the nanny-goat hath borne in the spring;<br />

καὶ ὥς ἐν ὕπνῳ Γαβριήλ ᾐωρέετ’ αἰπύς.<br />

even so was Gabriel suspended, lofty in trance.<br />

20 21

The Art of Simile<br />

John-Ellis, Lower Sixth<br />

One of the most integral constructs of the<br />

Homeric tradition is the simile – or, in<br />

Greek, παραβολή (parabolē, from which<br />

we gain the English ‘parable’). When one<br />

writes in the style of Homer, the objective<br />

is not simply to acquire a grasp for the<br />

Epic dialect, nor to develop a mastery<br />

of dactylic hexameter; rather, one must<br />

begin to understand Homer’s literary<br />

flair.<br />

Homer’s timeless success as a poet may<br />

be easily pinned down to his unparalleled<br />

artistry in storytelling, leading to the<br />

popularity of his works more than 2800<br />

years later. Scholars on all sides of the<br />

Homeric Question hold the central facets<br />

of the genre in great respect: the simile,<br />

the metaphor, intertextuality etc. Notably,<br />

however, these all come on much grander<br />

and more elaborate scales than one might<br />

typically find in English literature. For<br />

Homer, the simile is a device of visionary<br />

transportation: the pylon through which<br />

to lead the listener from diegetic tenor<br />

to mystic vehicle. The tenor (from Latin:<br />

teneō ‘I hold’) refers to the content which<br />

‘holds’ the actual narrative – in the<br />

case of the extract from my poem, the<br />

Transfiguration of Gabriel. Reciprocally,<br />

the vehicle (Latin: vehō ‘I transport’)<br />

evolves the ideas of its counterpart but<br />

transcends out of time, providing an<br />

allegory often with similar characters<br />

or events. In the Greek tradition, this<br />

was frequently a useful mechanism to<br />

stitch the threads of ancient folklore into<br />

the broad tapestry of narratives such as<br />

the Iliad and Odyssey. For instance, in<br />

Iliad Book III, the hostile congress of the<br />

Trojans and the Greeks is paralleled to<br />

the infamous clash of the Cranes and the<br />

Pygmies. In my own work, I took to a<br />

similar path, analogising Gabriel’s angelic<br />

figure to an idyllic, pre-Fall interpretation<br />

of Eve – the first woman.<br />

Naturally, there were deviations from<br />

Iliadic writing, namely the inclusion<br />

of Judeo-Christian references in place<br />

of Hellenic equivalents. This seemed,<br />

nonetheless, more appropriate in light<br />

of the faith of the titular character Abbot<br />

Wulsin (founder of our very own St Albans<br />

School) and the location which Gabriel’s<br />

radiant trance occurs: the Shrine of St.<br />

Alban. Fundamentally, it remained vital to<br />

the tone of poetry to emulate Homer’s use<br />

of intertext, here with Biblical references.<br />

Within the vehicle, itself fictitious, it was<br />

fitting to cite real elements of Genesis<br />

2; e.g ‘πολυχρύσου Εὐιλάτ’ (Havilah,<br />

rich in gold) nods to “the whole land<br />

of Havilah, where there is gold.” [Gn.<br />

2:11] in the Pentateuchal depiction of the<br />

Garden. Even then, subtle hints to Greek<br />

mythology have place. As an example,<br />

one may note the deliberate naming<br />

of Eve’s bathing spot as ‘Σόλλακος’<br />

(the Sollax), a recognition of this as its<br />

original name, before the abduction of<br />

Alphesiboea by Dionysus in the form of<br />

a tiger, upon which the site was renamed<br />

‘Tigris’ (from Greek: Τίγρις ‘tiger’).<br />

The epithet (from Greek: ἐπίθετον<br />

‘adjective’) is another signature<br />

characteristic of the Homeric stamp. In the<br />

original works, epithets add memorable<br />

denotations of legendary characters; they<br />

are responsible for the image of ‘swiftfooted’<br />

Achilles or ‘white-armed’ Hera.<br />

This is mirrored in the Ulsinea through<br />

the depiction of Eve: παντετοκυῖα<br />

(pantetokuia: ‘mother of all’). Such<br />

sobriquets may also be jocose or ironic,<br />

just as ‘ῥεθομαλίδας’ (rhethomālidas:<br />

apple-cheeked) is proleptic of Eve’s<br />

cheeks later being filled with the apple<br />

(fruit) of the tree.<br />

In full, the simile and many of Homer’s<br />

other signatures were vital in the pastiche<br />

of this beautiful genre.<br />

Below: Spring by Lawrence Alma-Tadema<br />

The Gallery<br />

Zach, Fourth Form<br />

As if we were on the Odyssey’s 10-year<br />

journey, our arduous adventure from<br />

St Albans to the London was full of<br />

excitement. From school we took a brisk<br />

walk to St Albans City Station, then the<br />

train to St Pancras, crossing over onto<br />

the Piccadilly Line to Leicester Square,<br />

with another short walk on the other<br />

side. From there, we finally reached our<br />

destination: the National Gallery.<br />

We were able to look at some of the<br />

most amazing paintings, for example,<br />

Paul Rubens’ The Judgement of Paris<br />

and William Turner’s Ulysses deriding<br />

Polyphemus. Both of these have huge<br />

classical importance – for instance, The<br />

Judgement of Paris is based upon Eris,<br />

the Goddess of Strife, who after not being<br />

invited to a wedding, decided to inscribe a<br />

golden apple with the title “to the fairest”,<br />

thus forcing a mortal man, Paris, to pick<br />

between the goddesses Hera, Athena and<br />

Aphrodite.<br />

For me, I thoroughly enjoyed our guide’s<br />

explanations of each painting. Not only<br />

was there an in-depth analysis of each,<br />

but after a while, I was able to ‘get an eye’<br />

for understanding the significance of each<br />

piece. For example, facial expressions,<br />

movement, direction, body language and<br />

lighting are all important elements in<br />

understanding the context and meaning<br />

of a picture. Not only can you infer<br />

relationships between characters, but you<br />

can also identify what is going on, what<br />

they’re about to do and what has just<br />

occurred.<br />

22 23

Capital Punishment<br />

Xavi, Lower Sixth<br />

The worst crime that a Roman<br />

citizen could commit was<br />

patricide, which in turn<br />

warranted the most extreme<br />

punishments. The most famous of<br />

these punishments was ‘poeni cullei’<br />

meaning the punishment of the sack –<br />

however, those convicted of patricide<br />

could also choose ‘damnatio ad bestias’<br />

where convicts would be thrown to wild<br />

animals in the colosseum. Poeni cullei<br />

involved the criminal being sewn into a<br />

sac containing an array of snakes, dogs<br />

roosters or chickens.<br />

The first case in which someone was<br />

punished by being bound in a sack and<br />

subsequently thrown into the river Tiber is<br />

disputed by different classical historians.<br />

The Roman historian Livy claims that a<br />

citizen called Publicius Malleolus was<br />

found to have committed parricide by<br />

killing his mother around the year 100BC<br />

and was then punished with poeni<br />

cullei. On the other hand, Dionysius of<br />

Halicarnassus links the punishment to the<br />

final king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus;<br />

a senior priest, called Marcus Atilius,<br />

was bribed to steal a sacred text and then<br />

disclosed the books’ secrets to a foreigner.<br />

For betraying his religion and the Roman<br />

state, Tarquinius ordered Atilius to be<br />

sewn into a bag and thrown into a river –<br />

it took many years for the punishment to<br />

become common for patricide.<br />

believed that this penalty was then made<br />

specific to the murder of parents and<br />

grandparents during the reign of Hadrian<br />

in the early decades of the 2nd Century.<br />

The reign of Emperor Hadrian saw a turn<br />

in the way about which the punishment<br />

for parricide was enacted – for the<br />

first time, convicts were able to choose<br />

between ‘poena cullei’ and being thrown<br />

into the arena to be eaten or killed by<br />

wild beasts. And in cases where there<br />

was no river to throw a sack into, it was<br />

mandatory for the guilty to be damned<br />

to the beasts. The evolving nature of the<br />

sentence saw the cruelty exacted by the<br />

Romans increase; when the punishment<br />

first started out, only snakes were placed<br />

into the sack but by the 3rd Century, the<br />

Below: Hadrian Visiting a Romano-British Pottery<br />

celebrated jurist Modestinus writes that<br />

‘[the sack contains] a dog, a dunghill cock,<br />

a viper and a monkey’. The alternative of<br />

‘damnatio ad bestias’ was similarly cruel<br />

– with defenceless offenders being thrown<br />

to lions, bears, Caspian tigers, elephants,<br />

hyenas, leopards, buffaloes, and wolves.<br />

While ‘damnatio ad bestias’ was a form of<br />

capital punishment, it was supposed to be<br />

a spectacle for Roman citizens as opposed<br />

to a just a public execution – it was often<br />

supposed to simulate the hunting of these<br />

wild beasts. The majority of the animals<br />

that took part in the punishment did<br />

not naturally hunt humans – they were<br />

subjugated to horrific conditions and<br />

reared to be aggressive to humans.<br />

The final time that poena cullei was<br />

promulgated in a law scripture was in<br />

the Corpus Juris Civilis, under the rule<br />

of Emperor Justinian in the 530s AD. This<br />

promulgation extended the penalty to<br />

include fathers who unjustly murdered<br />

their sons as well as the reverse of sons<br />

murdering their fathers. This would<br />

remain in common practice even after<br />

the fall of the Roman Empire in the<br />

5th Century – it was incorporated into<br />

the punitive system of the Byzantine<br />

Empire in the Eastern provinces of the<br />

fallen Roman Empire. The practice was<br />

abolished as the punishment fell out of<br />

favour in the Byzantine Empire around<br />

the year 890 AD – this, however, does<br />

not coincide with a shift in attitude for<br />

parricide – instead, those found guilty of<br />

this crime were burned alive.<br />

Below: Christ on the Cross<br />

It was the dictator Sulla who brought the<br />

punishment into fashion for punishing<br />

murderers who killed a family member<br />

after a period where it was the primary<br />

penalty for any murder. However, it is<br />

24 25

Moot Trial of<br />

Alexander the Great<br />

Jonathan, Lower Sixth<br />

In a dramatic reversal of expectations,<br />

Alexander the Great, the subject of<br />

a moot trial at the Supreme Court,<br />

was acquitted on four counts of war<br />

crimes associated with the capture of the<br />

Persian capital city, Persepolis, during the<br />

winter of 331-330 BCE.<br />

He was charged with the ransacking of<br />

the city, the massacre of civilians, the mass<br />

enslavement of Persian women and the<br />

destruction of the ancient royal palace, a<br />

cultural site, a few months after the capture<br />

of the city. Philippe Sands KC argued that<br />

the first three charges were not committed<br />

out of military necessity and should<br />

therefore be considered war crimes. He<br />

advanced the suggestion that Persepolis<br />

had already offered its co-operation prior<br />

to the acts of the Macedonian Greek<br />

forces and that Alexander’s motive was<br />

revenge for earlier Persian agression<br />

against the Greeks. Further, he proposed<br />

that concerns about the application<br />

of new laws to old crimes should be<br />

dismissed on the grounds of modern<br />

precedent in the post war justice systems<br />

of the twentieth century. The prosecution<br />

went on to address the fourth charge, the<br />

destruction of Persepolis’ palace, refuting<br />

the argument that it was a foolish drunken<br />

act, and instead suggesting that it was<br />

deliberate and politically motivated. The<br />

evidence offered for this was the lack<br />

of gold and silver in the archaeological<br />

remains, which implies premeditation,<br />

and Alexander’s bad character i.e. his<br />

propensity for destroying cities out of<br />

revenge, rather than military necessity.<br />

The defence, led by Patrick Gibbs KC,<br />

made an emotive appeal as to whether<br />

Alexander the Great really belonged<br />

with the modern figures traditionally<br />

considered to be war criminals. He<br />

suggested that we should not apply<br />

modern norms to ancient behaviours<br />

and called into question the sources cited<br />

Below: Alexander Cuts the Gordian Knot<br />

Above: Alexander the Great Founds Alexandria<br />

as evidence by the prosecution on the<br />

grounds of their temporal distance from<br />

the relevant events (Diodorus Siculus,<br />

Quintus Curtius Rufus, Plutarch and<br />

Arrian). The prosecution’s appeal to<br />

emotion was intensified by its exposition<br />

of the context of the events at Persepolis.<br />

Although both sides offered persuasive<br />

arguments, the jury, comprising<br />

those present at the venue, voted<br />

overwhelmingly for the acquittal of<br />

Alexander the Great. The Supreme Court<br />

Justice, Lord Leggatt, who was presiding,<br />

expressed his surprise at the verdict but it<br />

seems that Alexander’s wider reputation<br />

and his legal team’s emotive persuasion<br />

won the day.<br />

Gibbs pointed out that the co-operation<br />

offered by Persepolis after the Battle of<br />

Persian Gate was called into question<br />

by the reforming of the Persian forces<br />

to challenge the Greeks again, only<br />

to be defeated once more. He further<br />

suggested that Alexander would have<br />

felt that the Persians needed to be firmly<br />

stopped after 160 years of warfare. The<br />

26 27<br />

charge of the massacre of the city’s men<br />

was complicated by the lack of visibility<br />

of the chain of command. On the third<br />

charge of enslavement, the prosecution<br />

pointed to precedent in a culture in which<br />

the Iliad was seen as the ‘dictionary of<br />

heroism.’ Finally, the accusation of the<br />

wilful destruction of Persepolis itself was<br />

refuted as being out of character with<br />

both Alexander’s policy of exploiting his<br />

conquests rather than destroying them<br />

and his desire to be accepted by the ruling<br />

classes.<br />

Although both sides offered persuasive<br />

arguments, the jury, comprising<br />

those present at the venue, voted<br />

overwhelmingly for the acquittal of<br />

Alexander the Great. The Supreme Court<br />

Justice, Lord Leggatt, who was presiding,<br />

expressed his surprise at the verdict but it<br />

seems that Alexander’s wider reputation<br />

and his legal team’s emotive persuasion<br />

won the day.

Life of Cicero<br />

Classics Department<br />

On the 3rd of January 106 BC,<br />

Marcus Tullius Cicero was<br />

born to a wealthy father,<br />

62 miles away from Rome<br />

in a town called Arpino. Cicero was<br />

educated in the teachings of classical<br />

Greek poets and philosophers like most<br />

sons in wealthy, up-and-coming families<br />

during this time period. This education in<br />

both Latin and Greek enabled Cicero to<br />

integrate into elite Roman society.<br />

In 79 BC, when Cicero was 27 years old, he<br />

married a woman called Terentia which<br />

would have been ideal for Cicero as she<br />

was from a reputable family. Terentia was<br />

a strong character who took great interest<br />

in her husband’s career – the Roman<br />

historian Plutarch states that ‘she took<br />

more interest in her husband’s carrer than<br />

she allowed him to take in household<br />

affairs’. The pair remained harmoniously<br />

married for almost three decades, having<br />

two children, Tullia and Cicero Minor.<br />

In the year 51 BC, Cicero and Terentia<br />

divorced; Cicero states in letters to his<br />

friends that she had betrayed him, but he<br />

did not cite any specifics.<br />

Cicero’s oldest child and only daughter<br />

died suddenly of illness having given<br />

birth to a son just weeks prior; he wrote a<br />

letter to Atticus, devastated, saying ‘I have<br />

lost the one thing that bound me to life’.<br />

Caesar and Brutus were among those who<br />

wrote him letters of consolation. Cicero’s<br />

son, Cicero the Younger, had a successful<br />

military career under Pompey yet was<br />

defeated and subsequently pardoned by<br />

Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus. He went<br />

on to become a consul in 30 BC and also<br />

served as the governor of Syria.<br />

Legal and Political Life<br />

Cicero began his legal career as a defence<br />

barrister in the late 80s BC, though he<br />

got his first major case in 80 BC, as he<br />

defended a man called Sextus Roscius<br />

who was accused of patricide. This was a<br />

courageous and bold move for Cicero as<br />

not only was parricide an appalling crime<br />

but one of the accusers of Roscius was a<br />

favourite of Sulla. Other notable cases that<br />

Cicero took part in include ‘Pro Caecina’,<br />

‘Pro Cluentio’ and ‘Pro Quinctio’.<br />

His first stint in public office was as a<br />

‘quaestor’ in Western Sicily – he was<br />

held in esteem amongst the locals and<br />

was asked to prosecute the governor<br />

of Sicily, Gaius Verres, on charges of<br />

bribery and extortion. For Cicero, this<br />

trial was a phenomenal success, his ad<br />

hominem style of prosecution combined<br />

with brilliant oratory skills cemented<br />

his reputation as one of Rome’s best<br />

orators. Furthermore, he was up against<br />

Below: Cicero Discovers the Tomb of Archimedes<br />

one of Rome’s most reputable lawyers,<br />

Hortensius – the thumping win served<br />

as a platform for Cicero to boost his legal<br />

and political career.<br />

The year 63 BC was the most important<br />

in Cicero’s political career as he was<br />

elected consul along with Gaius Antonius<br />

Hybrida as his co-consul. The defining<br />

event of Cicero’s consulship was this<br />

foiling of the Catilinarian Conspiracy,<br />

spearheaded by Lucius Sergius Catilina.<br />

Catiline was the mastermind behind a<br />

violent coup which involved veterans,<br />

senators and plebs alike – Cicero<br />

made four damning speeches which<br />

denounced Catiline and his supporters.<br />

Following these speeches, Catiline fled<br />

Rome and Cicero was given the senatus<br />

consultum ultimum to use force against<br />

the conspirators and Catiline was killed<br />

in battle in January 62 BC.<br />

28 29<br />

Exile<br />

Although the Catiline Conspiracy was<br />

a success for Cicero, Caesar turned on<br />

Cicero in a bid to cement his stranglehold<br />

on Roman politics. Cicero had executed<br />

conspirators involved in the coup four<br />

years before – the consul threatened that<br />

any person who killed a Roman citizen<br />

without a proper trial would be exiled.<br />

He argued that he was exempt from this<br />

as he had been given senatus consultum<br />

ultimum, yet this argument was not<br />

accepted by the Senate. Clodius passed<br />

a law that meant that Cicero was not<br />

allowed to take shelter within 400 miles<br />

of Rome and stayed in Thessalonica – but<br />

the Senate voted to rebuke his exile a year<br />

later.<br />

Penultimate Years of His Life<br />

When Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49<br />

BC, Cicero fled Rome; however, he did<br />

not endorse either Caesar or Pompey<br />

Above: Fulvia with the Head of Cicero<br />

though he favoured Pompey, he tried<br />

not to alienate Caesar. He travelled with<br />

Pompey’s forces to Pharsalus, where<br />

Pompey would ultimately be defeated<br />

– after which Cicero returned to Rome<br />

and was pardoned. Cicero was caught<br />

completely off guard when Julius Caesar<br />

was assassinated as he was not a part of<br />

the conspiracy yet the conspirators treated<br />

him favourably in the aftermath.<br />

When Mark Antony took advantage of the<br />

unstable situation in Rome, Cicero stood<br />

in firm opposition of Antony’s consulship<br />

and claimed that Caesar’s wishes were<br />

being deliberately misinterpreted. Cicero<br />

urged the Senate to make Antony an<br />

enemy of the state as he led a campaign<br />

against a rebellious general. This plan<br />

failed and Antony along with Octavian<br />

made Cicero an enemy of the state –<br />

although Octavian argued against this.<br />

Cicero was captured and beheaded by a<br />

centurion and a tribune – his hands were<br />

cut off and were displayed in the Roman<br />

forum on the order of Mark Antony. The<br />

historian Cassius Dio claims that Antony’s<br />

wife cut Cicero’s tongue out and stabbed<br />

it with her hairpin as her final revenge<br />

against Cicero’s scathing orating.

Philology<br />

Jonathan, Lower Sixth<br />

Below: A Roman Studio<br />

Bottom: Cadmus Fighting the Dragon<br />

Earlier this year, the<br />

Hylocomian Society was<br />

proud to welcome back to St<br />

Albans Dr Tom McConnell<br />

as a guest speaker, our first<br />

in-person speaker after many<br />

months of Teams and Zoom based events.<br />

Dr McConnell is no stranger to the school,<br />

having been taught by Mrs Ginsburg,<br />

Mr Rowland and Mr Davies before<br />

embarking on his academic career. He<br />

began his journey after leaving the School<br />

by completing his degree in Classics at<br />

the University of Exeter before doing his<br />

Masters and researching his DPhil at the<br />

University of Oxford. He currently lectures<br />

at Oriel College and for the Classics<br />

Faculty.<br />

He gave us an introduction to the<br />

fascinating topic of comparative philology,<br />

beginning with an explanation of the<br />

complex family tree of Indo-European<br />

languages. Just as we are familiar with<br />

the modern Romance languages (French,<br />

Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian<br />

and Catalan) being derived from Latin,<br />

many languages, ancient and modern,<br />

widely spoken and more obscure, can<br />

be traced back to their common ancestor,<br />

Proto Indo-European. The family tree is<br />

represented in geographical terms and<br />

ranges from the Celtic languages including<br />

Old Irish, Welsh and Breton, to Tocharian,<br />

the most easterly of the family, originating<br />

in China. Dr McConnell described how a<br />

study of ancient and modern languages<br />

allows us to understand two key facets;<br />

morphology, or how languages are formed,<br />

especially their cases, and phonology<br />

which focuses on the sound of languages.<br />

When morphology and phonology<br />

correlate with meaning, it gives us the<br />

tools to reconstruct earlier languages.<br />

From this point we focused on how<br />

a smaller set of languages might be<br />

compared to understand its antecedents,<br />

which demonstrates how languages<br />

interrelate into a family tree. Everyday<br />

words in modern English, German and<br />

Dutch can be set side by side to deduce<br />

how their commonalities might point<br />

to moments of earlier development. For<br />

example, the English ‘water,’ the German<br />

‘Wasser’ and the Dutch ‘water’ are clearly<br />

similar and suggest a correspondence<br />

between the English ‘t,’ the German ‘ss’<br />

and the Dutch ‘t.’ Analysis suggests the<br />

Proto-West-Germanic language which<br />

preceded these used ‘t’ for that consonant.<br />

This method can be developed further to<br />

understand how the ancient languages of<br />

Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and modern English<br />

can be used to reconstruct their ultimate<br />

ancestor, Proto-Indo European. An<br />

example of this is the word ‘brother,’ which<br />

is b’ratar in Sanskrit, ‘frater’ in Greek,<br />

‘frater’ in Latin and may be reconstructed<br />

in a simplified way to be ‘b’rater’ in Proto-<br />

Indo European. We know that these<br />

commonalities are not chance alone since,<br />

if we apply the same method to Romance<br />

languages, we reconstruct Late Vernacular<br />

Latin.<br />

Dr McConnell’s lecture shed light on the<br />

fascinating reasons behind some of the<br />

similarities we often notice when learning<br />

Latin and Greek but, perhaps even more<br />

interestingly, it raised questions which<br />

are as yet unanswered, for example the<br />

placement of the Minoan and Mycenaean<br />

scripts, Linear A and Linear B: there are still<br />

many linguistic mysteries to be explored.<br />

30 31

Dido<br />

Katia, Lower Sixth<br />

When asked who Dido was,<br />

the Phoenician queen<br />

whose love affair with<br />

the Trojan Aeneid pulled<br />

her away from her promise to her late<br />

husband and towards her suicide is<br />

the most common answer. However,<br />

before Virgil was commissioned by the<br />

Emperor August to write the Aeneid,<br />

different classical writers spread stories<br />

of a different Dido. One who never<br />

met Aeneas, never was swayed from<br />

protecting her people instead dying for<br />

their safety, and never replaced her dead<br />

husband.<br />

Pompeius Trogus (a Gallo-Roman<br />

historian) writes of Dido – who he calls<br />

‘Alishat’ -fleeing Phoenicia and once<br />

completing a long Odyssey-like journey<br />

she arrives in North Africa. After her<br />

arrival, she commits a grand suicide on<br />

a pyre with many sacrifices to prevent<br />

being forced to a local chieftain. In this<br />

version, Dido founds her North African<br />

city-state 70 years before Aeneas’ journey,<br />

thus eradicating any chances of their<br />

intense love affair, and her character is<br />

not reduced to a love interest. Moreover,<br />

another intensive history written by<br />

Timaeus of Tauromenium mentions<br />

a queen, who he calls Theoisso and<br />

says was called Elissa or Alishat by the<br />

Phoenicians- the daughter of Pygmalion,<br />

King of Tyre. Similarly, she is forced to<br />

marry a local king and kills herself by<br />

jumping into an enormous pyre. There<br />

is no mention of Aeneas, or his arrival,<br />

and this Dido is presented as a strong and<br />

independent leader.<br />

Different interpretations of Dido didn’t<br />

fizzle out after Virgil’s propagandized<br />

presentation becomes popular. For<br />

instance, Livy makes no mention of Dido<br />

in connection to Aeneid, and Macrobius<br />

(an author of late Antiquity) claims Virgil<br />

was inspired by the relationship between<br />

Jason and Medea for Dido and Aeneas’<br />

relationship.<br />

Opposite: The Meeting of Dido<br />

and Aeneas<br />

32