Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

systems is that the case could occasionally<br />

be resolved in the preliminary hearing via<br />

the taking of oaths. Taking an oath to the<br />

gods was seen as a deeply serious matter<br />

and very few people would be willing to<br />

perjure themselves (the penalty for perjury<br />

was grave in both the eyes of the law<br />

and the gods). The plaintiff could throw<br />

the gauntlet to the defendant by making<br />

him swear an oath – if the defendant was<br />

willing to take this oath, then he won, but<br />

if he did not, then he lost. This could be<br />

reversed for the plaintiff where the same<br />

rules would apply.<br />

If the trial progressed beyond the<br />

preliminary hearing, it would play out in<br />

the same way as under the ‘legis actionis’<br />

system. In the case of the debt, a new<br />

procedure of holding a public auction<br />

of the possessions of the debtor’s estate<br />

would help the creditor to be reimbursed.<br />

The third and final major development<br />

in the procedure of the Roman judicial<br />

process was the introduction of the<br />

‘cognitio extraordinaria’ system. This<br />

system was introduced after the Roman<br />

Empire succeeded the Republic and bears<br />

the most similarity with modern justice<br />

structures. For the first time, defendants<br />

were summoned to the court by the court<br />

instead of the plaintiff having to summon<br />

them; plaintiffs had to file a statement of<br />

claim. If either one of the parties failed to<br />

show at court on the date three separate<br />

times then the party which turned up<br />

won by default. The other major change<br />

that the cognito system brought was the<br />

process of appeals – the case could in<br />

theory progress up through higher courts<br />

and potentially reach the emperor.<br />

Although law predates Rome by<br />

thousands of years through social<br />

convention and speech, Romans<br />

revolutionised the way in which the rule<br />

of law was implemented. It created a<br />

blueprint for the societies that followed<br />

through its systematic and impartial<br />

process; while none of the punishment<br />

have stood the test of time, the way in<br />

which the law is applied remains largely<br />

the same.<br />

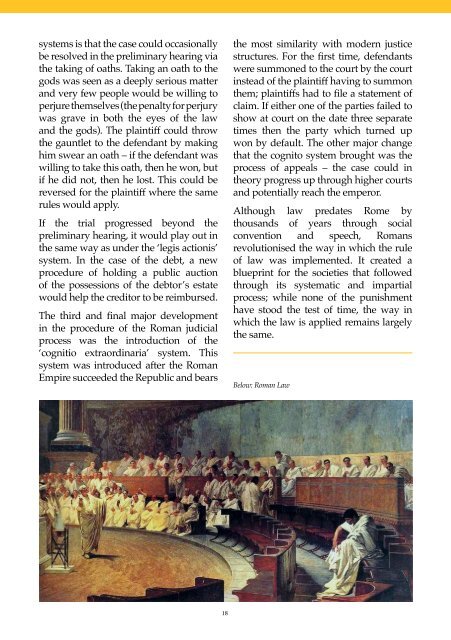

Below: Roman Law<br />

Xenophanes<br />

Jonathan, Lower Sixth<br />

In the Autumn term Dr Shaul Tor, Senior<br />

Lecturer in Ancient Philosophy at King’s<br />

College London, delivered an insightful<br />

lecture on the philosophy of Xenophanes<br />

to the Hylocomian Society. His theme<br />

was: What if cows could draw Gods?<br />

And what do we see in a rainbow? Some<br />

philosophical questions in Xenophanes.<br />

Dr Tor began with an exploration of<br />

Xenophanes’ biography. The Presocratic<br />

philosopher was active in Colophon<br />

(in Ionia) at the end of the sixth and<br />

beginning of the fifth century BCE. He<br />

travelled widely around Greece and<br />

wrote in verse, using both the hexameter<br />

and elegiac form. Xenophanes’ interests<br />

lay in theology, knowledge and belief,<br />

natural philosophy, ethics and politics.<br />

His work remains either in fragmentary<br />

form or preserved in the works of other<br />

writers such as Aristotle and Plutarch.<br />

Dr Tor then proceeded to reveal how<br />

the fragmentary evidence we have for<br />

Xenophanes’ work can be worked into a<br />

coherent picture of his stated perspective<br />

on the nature of the gods. By way of<br />

context it is important to consider the<br />

fact that the ancient Greek literary canon<br />

drew heavily on Homer’s epics, The<br />

Iliad and The Odyssey, and Hesiod’s<br />

poetry about the origins of the gods,<br />

Theogony. Both writers feature multiple,<br />

anthropomorphic, imperfect deities.<br />

However, fragments of Xenophanes’<br />

work show him noting mortal belief that<br />

gods are born and have bodily form and<br />

clothing similar to their own.<br />

He further notes that the poets portray<br />

the gods as committing acts which are<br />

reprehensible for mortals, for example<br />

theft, adultery and deceit. Aristotle’s<br />

18 19<br />

capture of Xenophanes’ philosophy<br />

suggests that he considered it to be<br />

impious to suggest that gods came into<br />

being or die. Furthermore, Xenophanes’<br />

fragments draw out his suggestion that<br />

all people create god in their own image;<br />

he suggests that the Thracians and<br />

Ethiopians, who tend to look physically<br />

very different, say that their gods look<br />

like them and, if they could draw, horses<br />

would render images of their gods to look<br />

like horse and oxen to look like oxen.<br />

What is particularly interesting in the<br />

further fragments is the similarity<br />

of Xenophanes’ philosophy to a<br />

monotheistic system. Although his<br />

assertion of “One god, greatest among<br />

gods and men,” does not exclude<br />

polytheism, his assertion of this being<br />

as “not at all like mortals either in frame<br />

or cognition” implies an unknowable<br />

quality in a supreme god. Moreover,<br />

he also alludes to an omniscience and<br />

omnipotence in this supreme god. This<br />

being is further located as unchangeable<br />

in space and time. These fragments have<br />

remarkable resonance in modern religion.<br />

Xenophanes is no less critical of the minor<br />

deities, often deployed by ancient writers<br />

to explain natural phenomena. In a further<br />

fragment, he critiques the goddess Iris,<br />

who manifests as a rainbow, believing her<br />

to be “by nature cloud, purple, and red,<br />

and greenish-yellow to behold.” This is<br />

a marked step away from the Olympian<br />

pantheon and their attendant demi-gods<br />

and goddesses, who cause thunder,<br />

storms, and the changing of the seasons.<br />

In short, Dr Tor left us with the impression<br />

of a very modern mind forged in an<br />

ancient context and much to consider<br />

to explore further the philosophy of the<br />

Presocratics.