Shabbat Chol

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

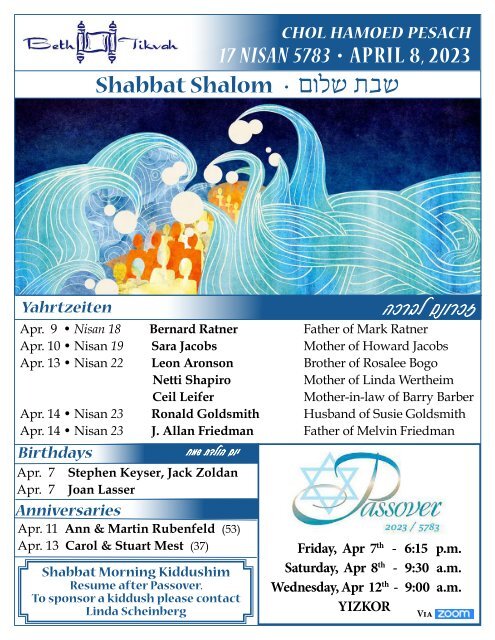

CHOL HAMOED PESACH<br />

17 NISAN 5783 • APRIL 8, 2023<br />

<strong>Shabbat</strong> Shalom • ouka ,ca<br />

Yahrtzeiten<br />

<strong>Shabbat</strong> Morning Kiddushim<br />

Resume after Passover.<br />

To sponsor a kiddush please contact<br />

Linda Scheinberg<br />

vfrck oburfz<br />

Apr. 9 • Nisan 18 Bernard Ratner Father of Mark Ratner<br />

Apr. 10 • Nisan 19 Sara Jacobs Mother of Howard Jacobs<br />

Apr. 13 • Nisan 22 Leon Aronson Brother of Rosalee Bogo<br />

Netti Shapiro<br />

Mother of Linda Wertheim<br />

Ceil Leifer<br />

Mother-in-law of Barry Barber<br />

Apr. 14 • Nisan 23 Ronald Goldsmith Husband of Susie Goldsmith<br />

Apr. 14 • Nisan 23 J. Allan Friedman Father of Melvin Friedman<br />

Birthdays<br />

Apr. 7 Stephen Keyser, Jack Zoldan<br />

Apr. 7 Joan Lasser<br />

Anniversaries<br />

jna `skuv ouh<br />

Apr. 11 Ann & Martin Rubenfeld (53)<br />

Apr. 13 Carol & Stuart Mest (37)<br />

Friday, Apr 7 th - 6:15 p.m.<br />

Saturday, Apr 8 th - 9:30 a.m.<br />

Wednesday, Apr 12 th - 9:00 a.m.<br />

YIZKOR<br />

Via

Torah & Haftarah Readings:<br />

Devarim: Exodus 33:12-34:26 (Etz Hayim p. 538)<br />

1. 33:12-16 2. 33:17-19 3. 33:20-23 4. 34:1-3<br />

5. 34:4-10 6. 34:11-17 7. 34:18-26 M. Numb.28:19-25 ( p. 932)<br />

Haftarah: Ezekiel 37:1-14 (Etz Hayim p. 1308)<br />

Torah Summary<br />

Meeting the Gaze of Moses<br />

Bex Stern-Rosenblatt<br />

This week, on <strong>Shabbat</strong> <strong>Chol</strong> HaMoed Pesach, we once again have the<br />

opportunity to read the beautiful and borderline irreverent passage in<br />

which Moses asks to see God’s kavod, God’s presence or glory. The leadup<br />

to Moses’s big ask is exquisite - Moses and God dance around the topic,<br />

one more polite than the next, as they reconfigure their relationship in the<br />

wake of the Golden Calf.<br />

The words both Moses and God use focus on sight. Moses starts his<br />

speech by asking God to “see,” to “look.” He’ll remind God to “see” that<br />

this people, Israel, is God’s nation. Repeatedly, Moses reminds God that<br />

God likes Moses, literally that Moses has “found favor in his eyes.” This<br />

emphasis on sight is striking. Rashi explains that Moses is reminding God<br />

to look back to God’s own words, to reflect that to which God has already<br />

acquiesced. Ibn Ezra reads “see” as Moses asking God to look at him, to<br />

behold the difficult situation in which Moses finds himself. Either way, the<br />

request to be seen is a call for remembering and for taking responsibility.<br />

God agrees to the request of Moses, explaining that God’s face, perhaps<br />

meaning God’s presence, will go with the Israelites. Moses had two<br />

requests, for God to see and to let him know who would lead the Israelites<br />

with him. God responds definitively to the latter request. God perhaps<br />

also responds to the first request, the call for sight, by sending his seeing<br />

mechanism to be with Moses. God puts God’s face at eye level with the<br />

Israelites, becoming their perpetual beholder.<br />

All this talk of God seeing Israel, of God bringing God’s face to Israel,<br />

contextualizes God’s response when Moses famously requests to see<br />

God’s kavod. Setting up an aspects-of-God parade, God will allow various<br />

attributes of God to pass before Moses’s face while Moses is wedged in a<br />

rock. But God will not allow Moses to see God’s kavod or God’s face. The<br />

relationship defined here is clear and asymmetrical. God is present, God’s<br />

face is present with the Israelites, so that God can see them and can behold<br />

Moses. But Moses is not to see God’s face.<br />

But Moses does glimpse something. We read that God permits Moses to<br />

see God’s ahor. Many modern translations render this word as “back.”<br />

Moses catches a view of God as God leaves. It is unclear what God’s back<br />

is supposed to be or why Moses would be allowed to look at it. One<br />

possibility, brought to us by Rashi, is that God shows Moses the knot of<br />

tefillin behind his head. However, “back” is not the only way the word has<br />

been understood. Targum Onkelos, a second century Aramaic version of<br />

the Torah, renders ahor and penai, which I have been translating as “face,”<br />

as directional terms, reading the verse to say, “You will see that which is<br />

after me, but what is before me shall not be seen.” The Avot de Rabbi<br />

Natan understands these terms as references to the world to come and to<br />

this world. Moses may see one but not the other. Diana Lipton, a current<br />

biblical scholar at Tel Aviv University, suggests based on careful readings of<br />

rabbinic texts, that we may understand the ahor as referring to the future<br />

and penai as referring to the past. God permits Moses to glimpse the future<br />

but not the present and not the past. God reassures Moses by showing him<br />

the continuity of the Jewish people long after Moses is gone.<br />

God does not reveal to Moses the mysteries of how people work in his<br />

present time or why the Golden Calf happened. Rather, God lets Moses<br />

know that we will be ok even after Moses is gone. God fully sees Moses,<br />

answering the true question that Moses is asking.<br />

On Pesach, we do the opposite. We gaze deeply into our past, reliving the<br />

Exodus. In doing so, we see the penai rather than the ahor. In looking<br />

towards the past, we see God’s face, dwelling securely among the Jewish<br />

people.<br />

For more on the idea of ahor as the future, check out Diana Lipton’s article,<br />

“God’s back! What did Moses see on Sinai?.”<br />

Exodus: Greater the Second Time Around<br />

Vered Hollander-Goldfarb<br />

After two seder nights we get the idea: the greatest event of the Jewish<br />

people was the wondrous Exodus from Egypt, the land of bondage (not<br />

just for us). It set us on course for the rest of our existence always looking<br />

back to that formative experience which will color our narrative and our<br />

legal system. We left the land of bondage for us and the land of plenty (if<br />

you were an Egyptian master) and headed to the land of Israel to finally live<br />

in the land intended for our nation.<br />

Then came the exile. We were thrown out of the land. The Exodus from<br />

Egypt unraveled. We were no longer a free and independent people living<br />

in our own land. While prophets warned of the possibility of exile because<br />

of our behavior, the reality of such a possibility did not sink in. Does anyone<br />

really imagine being forced out of their home? That was not built into the<br />

narrative.<br />

It is in the setting of the community exiled to Babylon that Ezekiel speaks.<br />

Explaining the unsettling description of the dry bones scattered on the<br />

floor of a valley, Ezekiel says that the dry bones are the people of Israel.<br />

They describe themselves as dried bones, as people whose hope is lost.<br />

(The word for hope is “tikvah”. Naphtali Zvi Imber gave a modern reading<br />

of this chapter in his poem that would eventually be the basis for Hatikvah<br />

– Israel’s national anthem.) Ezekiel promises this dispirited group that God<br />

will take them out of their graves and bring them to the land of Israel.<br />

Whether this is intended figuratively or literally is debated.<br />

This explains the need for Ezekiel’s prophecy, but not the choice to read<br />

this prophecy as the haftarah on <strong>Shabbat</strong> <strong>Chol</strong> Hamoed Pesach. It might<br />

have to do with the message of Pesach itself. We have spent a great deal<br />

of time telling the story of the Exodus, our story of redemption. Now we<br />

face a problem. Anyone following the story will be able to point out that<br />

the redemption that we are touting failed in the end. We are not in the land<br />

promised to our ancestors but rather in another exile. Don’t we see how<br />

pointless it is to talk about our Exodus and our going to the land when we<br />

have been kicked out of it and returned to a status of sojourners in foreign<br />

lands?!<br />

The prophecy of Ezekiel has come to speak to every generation that<br />

found itself as dry bones at the bottom of a valley. It promised a future<br />

redemption more miraculous and amazing than even the exodus from<br />

Egypt, the ultimate measuring stick of the Tanakh. As we tell ourselves the<br />

great story of God taking us out of Egypt, Ezekiel has helped Jews through<br />

the centuries believe that it can happen again, just greater. We have not<br />

lost our hope.<br />

Beth Tikvah of Naples<br />

1459 Pine Ridge Road • Naples, FL 34109<br />

ph: 239 434-1818