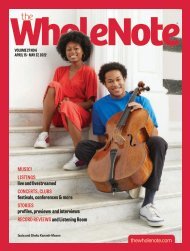

Volume 29 Issue 2 | October & November 2023

With this issue we start a new rhythm of publication -- bimonthly, October, December, February April, June, and August. October/November is a chock-a-block two months for live music, new recordings, and news (not all of it bad). Inside: Christina Petrowska Quilico, collaborative artist honoured; Kate Hennig as Mama Rose; Global Toronto 2023 reviewed; Musical weavings from TaPIR to Xenakis at Esprit; Fidelio headlines an operatic fall; and our 24th annual Blue Pages directory of presenters. This and more.

With this issue we start a new rhythm of publication -- bimonthly, October, December, February April, June, and August. October/November is a chock-a-block two months for live music, new recordings, and news (not all of it bad). Inside: Christina Petrowska Quilico, collaborative artist honoured; Kate Hennig as Mama Rose; Global Toronto 2023 reviewed; Musical weavings from TaPIR to Xenakis at Esprit; Fidelio headlines an operatic fall; and our 24th annual Blue Pages directory of presenters. This and more.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

for violin and theorbo by Italian, Austrian<br />

and German composers Mealli, Schmelzer,<br />

Caccini, Biber, Böddecker and Castaldi,<br />

an elusive repertoire that remains relatively<br />

unknown to the wider audiences and<br />

brings vigour and bloom to what might be<br />

considered somewhat predictable in the<br />

realm of historical performances. Krause and<br />

her partner in crime, theorbo virtuoso John<br />

Lenti, are just fabulous, their performance<br />

is nothing short of beautiful. Krause has a<br />

way of bringing the most interesting, almost<br />

visceral textures out of her Baroque violin.<br />

Her ornamentations are lovely and complemented<br />

well by Lenti’s strong presence.<br />

Although passionate and meaningful, this<br />

music is unpretentious. Krause and Lenti<br />

tell stories, visit mountain peaks and valleys,<br />

drink from the lakes and creeks, dance in<br />

town squares, all the while balancing virtuosity<br />

and tranquility. The music glows and<br />

grows throughout the album, reaching for<br />

hidden nooks and corners, filling our ears<br />

with delight.<br />

Ivana Popovic<br />

Mozart and the Organ<br />

Anders Eidsten Dahl; Arvid Engegård; Atle<br />

Sponberg; Embrik Snerte<br />

LAWO Classics (lawo.no)<br />

! When one thinks<br />

of Mozart, the<br />

mind can go many<br />

places, from opera<br />

to overture, sonata<br />

to symphony. One<br />

area of music with<br />

which Mozart is<br />

not often associated,<br />

however, is organ music. By all accounts,<br />

Mozart was a fine player who enjoyed the<br />

sounds of the instrument – going so far as to<br />

title it “The King of Instruments” – but the<br />

organ was not a vehicle for concertizing in<br />

Mozart’s time, instead used almost exclusively<br />

in church services.<br />

What Mozart did write for organ falls<br />

into two categories: the first is the collection<br />

of 17 “Epistle” sonatas, chamber music<br />

written between 1772 and 1780 for masses in<br />

Salzburg, played between the reading of texts;<br />

the second is music that Mozart wrote for<br />

the “Flotenuhr” – a large grandfather clock<br />

containing a self-playing organ. There are two<br />

large-scale works from this latter category<br />

that are played quite frequently today, the<br />

Adagio and Allegro in F Minor K594 and the<br />

magnificently monumental Fantasia in F<br />

Minor K608.<br />

Organist Anders Eidsten Dahl gives a<br />

tremendous overview of this music in Mozart<br />

and the Organ, which includes 14 of the 17<br />

church sonatas and both K594 and K608.<br />

Recorded in the Swedish Church in Oslo,<br />

Norway featuring violinists Arvid Engegård<br />

and Atle Sponberg and bassoonist Embrik<br />

Snerte, each of the sonatas is a little gem<br />

containing its own delightful character<br />

and range of expression, compressed into<br />

a miniature form. The larger organ works<br />

are wonderfully paced and expertly interpreted,<br />

and Dahl makes Mozart’s challenging<br />

writing sound effortless and clear, especially<br />

in perilous passages where rapid and<br />

constant movement make great demands of<br />

the performer.<br />

Mozart and the Organ is highly recommended<br />

to all who appreciate Mozart and<br />

organ music, whether together or separately.<br />

These works are masterpieces and well worth<br />

hearing, whether for the first time or the<br />

hundredth.<br />

Matthew Whitfield<br />

Mozart – Complete Piano Sonatas Vol.4<br />

Orli Shaham<br />

Canary Classics CC23 (canaryclassics.com)<br />

! Violinist Gil<br />

is not the only<br />

Shaham who is<br />

making waves<br />

wherever classical<br />

music is adored. His<br />

younger sister Orli<br />

has been showing<br />

the world that her<br />

steely, lyrical pianism is eminently suited<br />

to the performance of Wolfgang Amadeus<br />

Mozart. However, rather than put on a show<br />

with Mozart’s more celebrated piano music<br />

the younger Shaham is focusing her attention<br />

on Mozart’s lesser-performed sonatas en<br />

route to giving us a complete collection of the<br />

elegantly sparse works with their virtually<br />

endless supply of sparkling melodies,<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 4 of the ongoing series features<br />

three of the earliest sonatas – the F Major,<br />

No.2 K280, the C Major No.1 K279 and the D<br />

Major, No.6 K284, Dürnitz. Should there be<br />

any question as to why these (early) works<br />

grace the fourth volume of Shaham’s Mozart<br />

Complete Piano Sonatas the answer lies in<br />

the simple fact that they are no less technically<br />

demanding, being as they are of great<br />

harmonic ingenuity and melodic richness, as<br />

the later sonatas.<br />

The Allegro and (especially) the Rondeau<br />

en Polonaise: Andante movement of the<br />

Dürnitz are cases in point. The latter – in<br />

Shaham’s skilful hands – reflects a preeminently<br />

graceful Polish dance of Mozart’s<br />

vivid imagination. As with <strong>Volume</strong>s 1, 2 and<br />

3 Shaham’s delicate phrasing brings out the<br />

cornucopia of Mozart’s melodic delights from<br />

end to end on this disc, but especially in the<br />

filigreed brilliance of the Dürnitz sonata.<br />

Raul da Gama<br />

Mozart – Piano Concerto No.5 & Church<br />

Sonata No.17<br />

Robert Levin; Academy of Ancient Music<br />

AAM AAM042 (aam.co.uk)<br />

! At first glance,<br />

the music contained<br />

in this recording<br />

is somewhat<br />

perplexing: of all<br />

the incredible music<br />

Mozart composed,<br />

why choose one<br />

full piano concerto,<br />

a few juvenile transcriptions, and a church<br />

sonata that’s less than five minutes long?<br />

There is a reason, and it’s a good one.<br />

In 1993, Robert Levin and Academy of<br />

Ancient Music founder Christopher Hogwood<br />

set out to record Mozart’s complete works<br />

for keyboard and orchestra, with the first<br />

of a planned 13 recordings released in 1994.<br />

Despite its noble intentions, the project was<br />

cancelled midway through, as the advent of<br />

downloadable digital music formats in the<br />

early 2000s changed the market quickly and<br />

drastically. Now, over 20 years later, AAM and<br />

Levin are continuing the cycle, scheduled for<br />

completion in June 2024, which will become<br />

the first-ever recording of Mozart’s complete<br />

works for keyboard and orchestra on either<br />

modern or historical instruments.<br />

The most aurally striking aspect of this<br />

recording is that the Piano Concerto No.5 in D<br />

Major K175 doesn’t feature a piano at all, but<br />

rather an organ. This is for several reasons,<br />

including the necessity of a pedalboard to<br />

reach the lowest notes in the keyboard part,<br />

the limited upper range, and Mozart’s use of<br />

the term Clavicembalo, generic nomenclature<br />

that encompassed a range of keyboard<br />

instruments. Rather than being impractically<br />

theoretical, however, the use of the organ<br />

provides great clarity and prominence to the<br />

solo part and blends exceedingly well with<br />

the ensemble.<br />

The other noteworthy pieces on this<br />

recording are the Three Piano Concertos<br />

after J.C. Bach K107, through which the<br />

young Mozart learned his craft and honed his<br />

skills. Far from the masterpieces of his later<br />

years, these works were joint efforts between<br />

Wolfgang and his fathe, Leopold, who would<br />

revise his son’s transcriptions and add embellishments<br />

and other instructional guidance.<br />

Juxtaposing these early works with<br />

only slightly more mature compositions, the<br />

younger Mozart clearly learned quickly.<br />

A valuable component of a valuable project,<br />

this recording is informative and tremendously<br />

appealing, both individually and as<br />

part of its larger set.<br />

Matthew Whitfield<br />

62 | <strong>October</strong> & <strong>November</strong> <strong>2023</strong> thewholenote.com