Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

vector<br />

The Official Student Publication of the AMSA Global Health Network<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> <strong>10</strong> November <strong>2009</strong><br />

Non-communicable<br />

diseases edition<br />

Stroke and Heart Disease Impacts<br />

the Developing World<br />

GHN Update<br />

Global Health<br />

Conference <strong>2009</strong><br />

Talking with the<br />

Indian Consul General<br />

Medical student experiences<br />

from PNG and Cambodia<br />

Also inside: Creative stories from the medical profession on global health issues!

contents<br />

issue <strong>10</strong> november <strong>2009</strong><br />

3 Editor’s Note<br />

11<br />

9<br />

4 What Lurks in the Shadows: noncommunicable<br />

disease in the<br />

developing world<br />

5 Heart Disease and Stroke Threaten<br />

Developing World<br />

6 Tipping the Scales: the ‘expansion’<br />

of the global community<br />

8 Smoking and Tobacco’s Impact<br />

on the Developing World: the<br />

worlds top health priority<br />

9 A Conversation with the Indian<br />

Consul General<br />

<strong>10</strong> The Nageri Misiion<br />

11 Mental Health Crisis in China<br />

12 Medicine and Mosquitoes: a<br />

medical student’s month in<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

13 Stories from Cambodia<br />

14 Global Health In The News<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

16 13<br />

the<br />

non-communicable<br />

diseases<br />

edition<br />

2 vector november <strong>2009</strong><br />

Global Health Network Update<br />

15 Welcome to the GHN<br />

15 A Year in the GHN: Looking back<br />

and Looking Forwards<br />

16 The Global Health Conference:<br />

Challenging the world after<br />

Brisbane<br />

17 Global Health Series - University<br />

of Sydney<br />

17 Student Involvement - Helping<br />

VSAP to help others<br />

Creative Pieces<br />

18 The Boy who Jumped off the<br />

Bridge<br />

19 Noor<br />

20 at a Glance: India

editor’s<br />

note<br />

“<br />

Kruthika Narayan<br />

Vikram Joshi<br />

Rami Subhi<br />

The golden arches of McDonalds<br />

have become a ubiquitous metaphor<br />

for globalisation; previously in<br />

the economic sense, but perhaps<br />

now as a symbol of the global epidemic of<br />

‘lifestyle’ diseases. There is an inherent irony<br />

in that the very symbols of prosperity and<br />

growth have become emblems for illness, in<br />

the developed world with growing incidence<br />

of chronic non-communicable diseases<br />

(NCDs).<br />

The picture is both similar and different<br />

in the less developed world. Instead of representing<br />

the dangers of excess, the rampant<br />

increase in NCDs in less-developed countries<br />

Non-communicable diseases, with their precursors of<br />

high cholesterol, hypertension and obesity, are overwhelming<br />

the developing world much faster than the<br />

developed<br />

reflects the deficiencies of stretched health<br />

systems traditionally geared towards relief<br />

of acute illness in handling the immense<br />

burdens of chronic disease. It also highlights<br />

the effects of environmental exploitation<br />

limiting access to fresh healthy foods, and<br />

the dire struggle of the growing populations<br />

of the urban poor for whom chronic disease<br />

is yet another force perpetuating the vicious<br />

cycle of poverty.<br />

Non-communicable diseases, with their<br />

precursors of high cholesterol, hypertension<br />

and obesity, are overwhelming the developing<br />

world much faster than the developed.<br />

Added to this are high rates of smoking and<br />

the long standing struggle against chronic<br />

infections.<br />

The World Health Organisation estimates<br />

that NCDs, including cardiovascular disease,<br />

diabetes, cancer and respiratory diseases,<br />

are responsible for over half of all deaths and<br />

46% of the global disease burden.<br />

Health issues in the developing world<br />

have thus far concentrated on communicable<br />

diseases; and rightly so, since many of these<br />

are preventable and/or readily treatable. But<br />

with the rise of NCDs including HIV/AIDS, an<br />

emerging concern about the influence of climate<br />

change and the environment on health<br />

outcomes, and the appreciation<br />

of the economic<br />

implications of chronic<br />

diseases particularly when<br />

compounded with poverty<br />

and failing health systems,<br />

it is time to promote the<br />

”<br />

complexities of NCDs on the<br />

global agenda.<br />

In this issue of <strong>Vector</strong>,<br />

we consider the impact of<br />

non-communicable diseases in settings least<br />

equipped to bear the burden of mortality,<br />

morbidity and economic strain they impose.<br />

The challenges are immense. The experience<br />

of the Western World attests to the difficulty<br />

in preventing and treating chronic disease; a<br />

difficulty compounded by the resource limitations<br />

of low income countries. The multifactorial<br />

causes of NCDs require a shift in<br />

attitude, not just in local government policies<br />

but in the ethics of operation of industries,<br />

corporations and nations, and a shift in the<br />

perceptions of the global society as a whole.<br />

<strong>Vector</strong>: The Official Student Publication of the AMSA Global<br />

Health Network<br />

GHN Publicity Officer<br />

Editors<br />

Design & Layout<br />

Catherine Pendrey<br />

Kruthika Nayaran<br />

Vikram Joshi<br />

Rami Subhi<br />

Alexander Murphy<br />

Editorial enquiries: Email vectormag@gmail.com<br />

GHN enquiries: ghn.publicity@gmail.com<br />

or visit www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

We welcome your written submissions, letters<br />

and photos on any global health issue or topic.<br />

Please limit submissions to 500 words or less.<br />

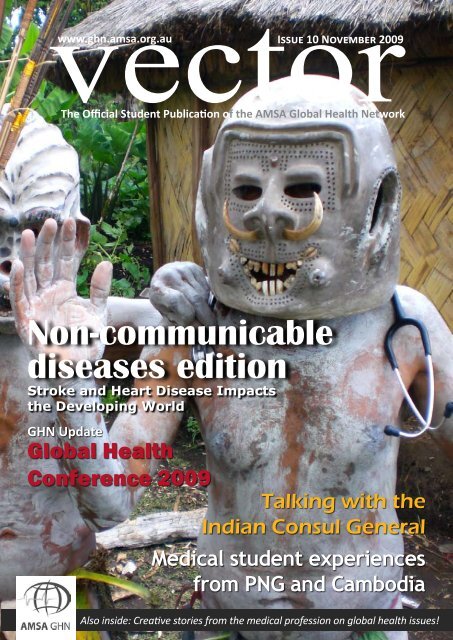

Cover Photo: The locals in Papua New Guinea<br />

// Image by Georgia Ritchie, Medical Student,<br />

University of Sydney<br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector3<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

What lurks in the shadows:<br />

non-communicable disease in the developing world<br />

Words Fred Hersch, Medical student, University of Sydney<br />

// Image by xymonau (sxc.hu)<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

1.Tunstall-Pedoe H. Preventing Chronic Diseases.<br />

A Vital Investment: WHO Global Report. Geneva: World<br />

Health Organization, 2005. pp 200. CHF 30.00. ISBN 92<br />

4 1563001. Also published on http://www.who.int/chp/<br />

chronic_disease_report/en. Int J Epidemiol. 2006 Jul 19.<br />

2.AD Lopez CM, M Ezzati, DT Jamison and CJL<br />

Murray, Editors. Global burden of disease and risk factorsnext<br />

term, Oxford University Press, New York2006.<br />

3.Gaziano TA. Economic burden and the costeffectiveness<br />

of treatment of cardiovascular diseases in<br />

Africa. Heart. 2008 Feb;94(2):140-4.<br />

4.Leeder Sea. A Race Against Time: The Challenge<br />

of Cardiovascular Disease in Developing Countries (New<br />

York: Trustees of Columbia University)2004.<br />

5.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum<br />

A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors<br />

associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries<br />

(the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet.<br />

2004 Sep 11-17;364(9438):937-52.<br />

6.Steyn K, Sliwa K, Hawken S, Commerford P,<br />

Onen C, Damasceno A, et al. Risk factors associated<br />

with myocardial infarction in Africa: the INTERHEART<br />

Africa study. Circulation. 2005 Dec 6;112(23):3554-61.<br />

7.Thomas A. Gaziano KSR, Fred Paccaud, Susan<br />

Horton, and Vivek Chaturvedi. 2006., editor. "Cardiovascular<br />

Disease."2006.<br />

8.Joshi R, Jan S, Wu Y, MacMahon S. Global<br />

inequalities in access to cardiovascular health care:<br />

our greatest challenge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Dec<br />

2;52(23):1817-25.<br />

9.Greenberg H, Raymond SU, Leeder SR.<br />

When we think about<br />

the global burden<br />

of disease and the<br />

plight of the poorest<br />

of the poor our minds often<br />

turn to the scourge of HIV/AIDS,<br />

malaria and tuberculosis - after<br />

all, that’s where all the attention<br />

is. Yet in the shadows lurks<br />

an uneasy truth: the rise of noncommunicable<br />

disease (NCD).<br />

Historically thought to be a disease<br />

of the “developed world”, NCD is in fact<br />

a worldwide pandemic of devastating<br />

proportions. In 2005 alone there were an<br />

estimated 35 million deaths from heart<br />

disease, stroke, cancer and other chronic<br />

diseases - approximately 50% (17.5 million)<br />

due to cardiovascular disease(1). Of<br />

these, 80% occurred in low- middle- income<br />

countries– (LMIC) twice as many<br />

deaths as from HIV, malaria and tuberculosis<br />

combined(1, 2). Cardiovascular<br />

disease (CVD), responsible for 30% of<br />

the total deaths worldwide(1)1, is the<br />

second leading cause of death in Africa,<br />

and the leading cause of death in those<br />

aged 30 or older(3). The fastest growing<br />

region for CVD is in the African region<br />

(27%) and it is estimated that over the<br />

next <strong>10</strong> years the burden from NCD will<br />

rise by 17% whilst those from communicable<br />

diseases will fall by 3% which<br />

translates to approximately 28 million<br />

deaths due to NCD over that period(1).<br />

The consequences of this are profound<br />

and far-reaching. Consider this:<br />

In contrast to our experience of NCD<br />

Cardiovascular disease and global health: threat and<br />

opportunity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005 Jan-Jun;Suppl<br />

Web Exclusives:W-5-31-W-5-41.<br />

<strong>10</strong>.Gaziano TA. Reducing the growing burden of<br />

cardiovascular disease in the developing world. Health<br />

Aff (Millwood). 2007 Jan-Feb;26(1):13-24.<br />

11.Beaglehole R, Ebrahim S, Reddy S, Voute J,<br />

Leeder S. Prevention of chronic diseases: a call to action.<br />

Lancet. 2007 Dec 22;370(9605):2152-7.<br />

12.Lim SS, Gaziano TA, Gakidou E, Reddy KS,<br />

Farzadfar F, Lozano R, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular<br />

disease in high-risk individuals in low-income<br />

and middle-income countries: health effects and costs.<br />

Lancet. 2007 Dec 15;370(9604):2054-62.<br />

13.Gaziano TA, Galea G, Reddy KS. Scaling up interventions<br />

for chronic disease prevention: the evidence.<br />

Lancet. 2007 Dec 8;370(9603):1939-46.<br />

14.Beaglehole R, Epping-Jordan J, Patel V, Chopra<br />

M, Ebrahim S, Kidd M, et al. Improving the prevention<br />

and management of chronic disease in low-income and<br />

middle-income countries: a priority for primary health<br />

care. Lancet. 2008 Sep 13;372(9642):940-9.<br />

15.Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, Ezzati M,<br />

Beaglehole R. Chronic disease prevention: health<br />

effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt<br />

intake and control tobacco use. Lancet. 2007 Dec<br />

15;370(9604):2044-53.<br />

16.Gaziano TA, Opie LH, Weinstein MC. Cardiovascular<br />

disease prevention with a multidrug regimen in the<br />

developing world: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet.<br />

2006 Aug 19;368(9536):679-86.<br />

being a disease of old age, in LMIC, it<br />

is often men and women in their most<br />

productive years (40‘s and 50‘s) who<br />

are most affected(4). On a personal level<br />

this is a tragedy for a family struggling<br />

for survival. At a societal level this<br />

lost productivity further compounds<br />

the challenges of economic growth.<br />

Inattention, rather than complexity<br />

contributes to the lack of action to date.<br />

A common set of known risk factors:<br />

hypertension, elevated lipids, smoking,<br />

obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and diabetes<br />

accounts for about 80% of clinical<br />

cardiovascular disease in every region of<br />

the world(5, 6). As developing countries,<br />

particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa<br />

move to the next stage of the epidemiological<br />

transition greater numbers<br />

of people are being exposed to diseaseproducing<br />

risk factors (2, 4, 7-11).<br />

The challenges are vast yet not<br />

insurmountable. We know from our<br />

experience that prevention works and<br />

there is a growing literature pointing<br />

to opportunities for scaling up low<br />

cost interventions. Tobacco control<br />

measures and dietary interventions can<br />

lead to small but significant changes in<br />

large groups of people(12-15). Health<br />

systems in LMIC traditionally oriented<br />

towards communicable disease<br />

will require re-orienting to address the<br />

chronic nature of NCD(1, 8, 12-14, 16).<br />

As we struggle towards goals such<br />

as “health for all” it would be nice to<br />

think that we can address the challenges<br />

of disease in a linear fashion - communicable<br />

then non-communicable.<br />

The inconvenient truth in all of this is<br />

that health, like life, is more complex<br />

than that. It is time that we lift the<br />

spotlight off to reveal the true picture of<br />

the global burden of disease and direct<br />

our efforts at addressing the health<br />

needs of communities as a whole. <br />

4 vector november <strong>2009</strong>

Heart disease and stroke<br />

threaten developing world<br />

Words Stephen R. Leeder and Angela Beaton<br />

Stephen Leeder is a Professor of<br />

Public Health and Community Medicine<br />

at the University of Sydney and Director<br />

of the Menzies Centre for Health Policy.<br />

He has a long history of involvement<br />

in public health research, educational<br />

development and policy. His research<br />

interests as a clinical epidemiologist<br />

have been mainly asthma and cardiovascular<br />

disease. His interest in public<br />

health was stimulated by spending 1968<br />

in the highlands of Papua New Guinea.<br />

Dr Angela Beaton is a Research Officer at<br />

the Menzies Centre for Health Policy.<br />

Heart attack and stroke,<br />

thought to be typically<br />

western diseases, are<br />

fast becoming major<br />

threats in developing countries.<br />

Four times as many deaths in<br />

mothers occur in most developing<br />

countries than do childbirth and<br />

HIV/AIDS: HIV/AIDS causes<br />

three million deaths a year; stroke<br />

and heart attack cause 17 million.<br />

Yet heart disease and stroke have<br />

attracted virtually no interest from<br />

international agencies committed<br />

to improving global health.<br />

It is time for that to change.<br />

Developing economies are seeing the<br />

kind of devastation to their workforces<br />

that Western countries experienced 50<br />

years ago. Troubling as these patterns<br />

are, they are but the first rumbles of the<br />

storm. The worldwide shift of working<br />

people from rural to city living has<br />

paralleled rising levels of prosperity and<br />

with it, greater consumption of food. A<br />

worldwide epidemic of obesity, even<br />

where under-nutrition persists in poorer<br />

quarters, presages high levels of diabetes,<br />

heart disease and stroke ahead.<br />

Fortunately, we can prevent and treat<br />

much heart disease and stroke. Treatment<br />

of raised blood pressure and blood<br />

lipids with drugs radically reduces risk<br />

and smokers who quit halve their risk<br />

of heart disease and stroke within two<br />

years. The World Health Organization<br />

has shown commendable leadership<br />

in relation to global tobacco control<br />

and now has its sights set on nutrition<br />

and exercise. Governments can assist<br />

by taxing tobacco and promoting good<br />

lifestyle habits, ensuring that all citizens<br />

have easy access to clinics, and plan<br />

healthier cities. Poor urban environments<br />

exacerbate physical and mental<br />

illnesses, now a major burden of global<br />

illness, at the expense of the economies<br />

of developing countries and our planet.<br />

To wait until heart disease and stroke<br />

decimate workforces before we take the<br />

global epidemic of heart disease and<br />

stroke seriously, would be both a health<br />

and economic tragedy. Heart disease and<br />

stroke are already propelling families<br />

into poverty in developing countries<br />

as young breadwinners and mothers<br />

die. Many developing countries have<br />

yet to create programs to control these<br />

diseases through long-term changes in<br />

macroeconomic policies, and by providing<br />

effective clinical care. Prevention<br />

programs must be locally sustainable<br />

for an indefinite future, and so developing<br />

countries should be encouraged to<br />

take the first step themselves, now.<br />

There is a responsibility for Australian<br />

medical students in advocating for<br />

action. Medical professionals have an<br />

important role in educating the public<br />

and lobbying governments to take up the<br />

challenge. Countries need the encouragement<br />

that stronger vocal advocacy for<br />

change can provide, to prod governments<br />

and donors into action, and international<br />

aid agencies should add to their agendas<br />

efforts to work with developing countries<br />

to contain these urgent and heavy threats<br />

to global health, national prosperity<br />

and family life in the developing world.<br />

Commitment from the highest levels of<br />

government in these countries is essential<br />

for comprehensive heart disease and<br />

stroke prevention. It will be important to<br />

graduate medical practitioners that have<br />

the capacity to deal with the consequences<br />

of an increased burden of chronic<br />

illness and an ageing population, and to<br />

assist communities to help themselves.<br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector5<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

tipping the scales<br />

the ‘expansion’ of the global community<br />

Words Rhea Pserickis, Medical student, University of Tasmania<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

I<br />

looked up from the desk and<br />

watched as my next patient<br />

walked in through the door.<br />

She was a middle-aged<br />

obese woman and beads of sweat<br />

had formed along her forehead<br />

in spite of the cooler weather. It<br />

took her a while to shuffle in, navigate<br />

the chair and find a comfortable<br />

sitting position. I noticed her<br />

heavy breathing. This patient was<br />

presenting with back and knee<br />

pain and had come in hoping for<br />

some analgesia. As I continued the<br />

consult, I pondered how to broach<br />

the fact that her weight was<br />

probably contributing to, if not<br />

directly causing, her pain. Just<br />

another obese patient with more<br />

chronic disease. Right? Well, not<br />

quite. The disparity is that this<br />

patient wasn’t in Australia nor<br />

was she a white Caucasian. I had<br />

in fact been working at a mobile<br />

clinic in remote Western Kenya,<br />

and this was a native Kenyan;<br />

more alarming, she was not the<br />

first or last obese Kenyan I came<br />

across during my time in Africa.<br />

Once considered a problem only<br />

in wealthy countries, the number of<br />

overweight and obese individuals has<br />

escalated in low and middle income<br />

countries. As risk factors for cardiovascular<br />

disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke<br />

and other chronic diseases, the rising<br />

prevalence of overweight and obesity in<br />

less developed countries is a hallmark of<br />

the now increasingly recognised ‘global<br />

society’ (1). Furthermore, the morbidity<br />

and mortality associated with these<br />

chronic diseases are significantly higher<br />

6 vector november <strong>2009</strong>

Right: Influences on the energy equation in<br />

developing countries (3). Below and facing<br />

page: One can appreciate the irony in all this<br />

when you see both the malnourished and<br />

obese side by side in a Gambian hospital (2).<br />

in less developed countries due to lack of<br />

education and understanding, as well as<br />

the age-old problem of resource insufficiency.<br />

In sub-Saharan Africa case-specific<br />

mortality rates for diabetes are more<br />

than <strong>10</strong> times higher than in the UK (2).<br />

The WHO indicates that globally,<br />

greater than 75 percent of women over<br />

the age of 30 are now overweight (1).<br />

Estimates are similar for men. In the<br />

Pacific islands of Nauru and Tonga nine<br />

out of every <strong>10</strong> adults are overweight<br />

(1). Obesity is even spreading rapidly<br />

through many an African countryside,<br />

along with its bevy of chronic disease<br />

burden which is both devastating and<br />

costly (2). Indeed, the existence of<br />

obesity and malnourishment within the<br />

one community presents an unintelligible<br />

paradox (see figure 1) (3).<br />

The increase in obesity in developing<br />

nations is due to ‘a global shift<br />

in diet towards increased energy, fat,<br />

salt and sugar intake, and a trend<br />

towards decreased physical activity<br />

due to the sedentary nature of<br />

modern work and transportation, and<br />

increasing urbanisation.’ (1) The developing<br />

world is now more than ever a<br />

target of many food companies and less<br />

developed countries present the largest<br />

growth markets for soft drink producers<br />

(4). Even where the Global Financial<br />

Crisis has tainted the US and European<br />

markets, consumption of soft drinks<br />

has increased in countries as diverse as<br />

Mexico, Egypt and China, encouraged<br />

by aggressive marketing campaigns,<br />

often aimed at children and youth (4).<br />

It is estimated that by 2015, 1.5<br />

billion individuals globally will be<br />

overweight (1). At this point, non-communicable<br />

diseases associated with the<br />

overweight and obese will surpass malnutrition<br />

as the leading cause of death in<br />

low-income communities (5). The contribution<br />

of chronic disease on the health<br />

status of the global community may paint<br />

a bleak picture, but it is our responsibility<br />

to take action to combat it. And where<br />

obesity is such a paradox to concurrent<br />

poverty, malnutrition, environmental<br />

instability and development, this responsibility<br />

becomes even more urgent. <br />

1.Anon. The World Health Organization warns of<br />

the rising threat of heart disease and stroke as overweight<br />

and obesity rapidly increase. (Media release).<br />

Geneva: September 22 2005. Article retrieved online<br />

on September 17 <strong>2009</strong> from, http://www.who.int/<br />

mediacentre/news/releases/2005/pr44/en/<br />

2.Prentice A and Webb F. Obesity admist poverty.<br />

Int J Epidemiology. 2006; 35:24-30<br />

3.Witkowski TH. Food Marketing and obesity<br />

in developing countries: analysis, ethics and public<br />

policy. J Macromarketing. 2007; 27(2):126-137<br />

4.Anon. Soft drinks and obesity: global threats<br />

to diet and health. (online article). Retrieved online<br />

on September 17 <strong>2009</strong> from, http://www.dumpsoda.<br />

org/health.pdf<br />

5.Tanumihardjo SA, Anderson C, Kaufer-Horwitz<br />

M, Bode L, Emenaker NJ, Haqq AM, Satia JA, Silver<br />

HJ and Stadler DD. Poverty, obesity and malnutrition:<br />

an international perspective recognising the paradox.<br />

J Amer Dietetic Assoc. 2007; <strong>10</strong>7(11):1966-1972<br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector7<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

Smoking and Tobacco’s Impact on the<br />

Developing World: The World’s Top Health Priority<br />

Words Cam Hollows, Medical student, University of Sydney<br />

“In the 20th century, the tobacco epidemic killed <strong>10</strong>0 million people worldwide…<br />

during the 21st century, it could kill One Billion.”<br />

“Reversing this entirely preventable epidemic must now rank as a top priority for<br />

public health and for political leaders in every country of the world.”<br />

Dr Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General (1)<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

// Image by Vivekchugh (sxc.hu)<br />

1. Organization WH. WHO Report on the Global<br />

Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package.<br />

Geneva: World Health Organization2008 Contract No.:<br />

ISBN 9789241596282.<br />

2. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS TaM. The Global<br />

Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria: Annual<br />

Report 2008. Vernier, Switzerland: The Global Fund to<br />

Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria2008 2008 Contract<br />

No.: 92-9224-163-X (ISBN).<br />

3. UNAIDS. UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS<br />

epidemic: 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS2008<br />

August 2008 Contract No.: 978 92 9 173711 6.<br />

4. Organization WH. WHO Report <strong>2009</strong>: Global<br />

Tuberculosis Control Epidemiology,<br />

Strategy, Financing. Geneva, Switzerland: World<br />

Health Organization<strong>2009</strong> Contract No.: 978 92 4 156380<br />

2.<br />

5. Organization WH. WHO 2008 World Malaria<br />

Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization2008<br />

Contract No.: 978 92 4 156369 7.<br />

6. Nations TU. The Millennium Development Goals<br />

Report 2208. New York, USA: United Nations2008<br />

August 2008 Contract No.: 978921<strong>10</strong>11739.<br />

7. Chapman S. Public Health Advocacy and<br />

Tobacco Control: Making Smoking History. Oxord:<br />

Blackwell Books; 2007.<br />

These statements are on<br />

the opening page of the<br />

World Health Organization<br />

Report on the<br />

Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008.<br />

Tobacco use is recognized as<br />

harmful throughout the medical<br />

profession. The links of smoking<br />

with increased incidence of<br />

cardio-vascular disease, peripheral<br />

vascular disease, respiratory<br />

diseases, many cancers, as well as<br />

effects on reproductive health (to<br />

name but a few) have also been<br />

clearly established. Recently, new<br />

data have made clear just how<br />

harmful smoking is in a global<br />

epidemiological sense and the<br />

disproportionate impact it has on<br />

health in developing countries.<br />

Tobacco use currently kills around<br />

5.4 million people every year. To put<br />

this in perspective, in 2005 HIV/AIDS,<br />

TB & Malaria (the diseases targeted<br />

in Millennium Development Goal 6)<br />

killed approximately 4.2 million together<br />

(2-6). Whilst I am aware of the dangers<br />

of impetus splitting, and I would<br />

not for a second want to detract from<br />

the importance of programs combating<br />

these diseases (particularly having had<br />

falciparum malaria myself!), the huge<br />

impact of tobacco related disease cannot<br />

be ignored. It is estimated that smoking<br />

related deaths will rise to as much<br />

as 8 million every year by 2030. These<br />

mortality data are of course not the full<br />

picture and as medical students our own<br />

clinical experience should allow us to extrapolate<br />

the burden of associate morbidities.<br />

We should also pause for thought<br />

as to the resource demands imposed by<br />

smoking in already stretched systems.<br />

Whilst the individual circumstance<br />

is often tragic and coupled with physiological<br />

and psychological addiction,<br />

the reality is that diseases occurring<br />

due to tobacco use are entirely preventable.<br />

Tobacco is the only product on<br />

the planet which if used according to<br />

the manufacturer’s instructions kills<br />

half of the people who use it (7).<br />

The unfortunate reality for those<br />

of us working in global health is that<br />

over 80% of smoking related deaths<br />

are occurring in the developing world<br />

(1). But the burden goes further than<br />

the morbidity, mortality and economic<br />

impact. For the poor, money spent on<br />

tobacco means money not spent on<br />

basic necessities such as food, shelter,<br />

education and health care. In one study<br />

in Bangladesh low-income families<br />

were spending as much as ten times on<br />

tobacco as they were on their children’s<br />

education (1). Given our awareness of<br />

the importance of education in health<br />

and sustainable development, and the<br />

prevalence of extreme poverty, this sort<br />

of study should chill us to the very core.<br />

In Australia, tobacco control is a<br />

public health success story. That our<br />

rates of smoking are so low and rates of<br />

tobacco related disease are dropping is<br />

to be lauded (7). Most other countries<br />

in the world are much worse off than<br />

we are in terms of what they can spend<br />

on tobacco control. Whether we are<br />

interested in it or not, the problems of<br />

tobacco related illness cannot be ignored;<br />

the numbers and impacts are simply too<br />

large. So where and when we can, we<br />

must remember to add tobacco control to<br />

our list of priorities as we try to address<br />

the challenges of equitable and sustainable<br />

health in the developing world. <br />

8 vector november <strong>2009</strong>

Many of you<br />

may recognise<br />

the<br />

painting as<br />

Van Gogh’s Wheatfields<br />

with Crows. Each of you<br />

will be struck by some aspect<br />

of the painting and form your<br />

own impression of it. What if you<br />

were then told that this was Van<br />

Gogh’s last painting before his<br />

suicide? Given this key piece of<br />

information, do your perceptions<br />

then change? The flying birds<br />

perhaps, are crows, harbingers<br />

of death; the chaotic landscape a<br />

reflection of his inner turmoil. In<br />

reality, Wheatfields<br />

is not<br />

Van Gogh’s<br />

last painting.<br />

Does this fact<br />

once again<br />

completely alter<br />

the perceptions<br />

proceeding<br />

from the<br />

previous one?<br />

This was the<br />

eloquent example<br />

with which<br />

the Consul-<br />

General of India,<br />

Sydney, Mr<br />

Amit Dasgupta,<br />

commenced his<br />

talk to medical<br />

students at the University of Sydney. As<br />

part of the Global Health Stream, the<br />

Medical Faculty’s international health<br />

curriculum, we had the valuable opportunity<br />

of speaking with the Consul-General<br />

on Thursday 17 September about health<br />

issues in India. Prior to his appointment<br />

in Sydney, Mr Dasgupta has held various<br />

diplomatic positions across the world,<br />

from Cairo to Kathmandu. His wide<br />

experience is reflected in the numerous<br />

books he has edited and written in both<br />

fiction and non-fiction. Caught up as<br />

we are in the world of medical facts, the<br />

Consul-General’s talk was an important<br />

eye-opener into the more philosophical<br />

issues surrounding health policy.<br />

a conversation with the<br />

Indian Consul General<br />

Words Kruthika Narayan, Medical student, University of Sydney<br />

Van Gogh’s Wheatfields was a<br />

poignant illustration of how essential<br />

pieces of information shape the way<br />

we perceive a situation and how these<br />

perceptions may not always be correct.<br />

As the Consul-General emphasised, this<br />

is particularly important in addressing<br />

the various issues of international health.<br />

It highlights that a health model which<br />

works in one developing country situation,<br />

may not necessarily be transplanted<br />

with equal effectiveness to another. In<br />

India, as the Consul-General explained,<br />

the diversity in language, culture and<br />

customs within states, let alone between<br />

them, makes the implementation of<br />

health policy a complex issue, requiring<br />

a different approach in each region.<br />

The burgeoning of chronic disease<br />

in India highlights the importance of<br />

targeted health intervention programs.<br />

According to <strong>2009</strong> WHO statistics,<br />

the age–standardised mortality rate for<br />

cardiovascular disease is 382/<strong>10</strong>0 000<br />

and studies suggest that chronic diseases,<br />

particularly cardiovascular, are<br />

fast becoming the main cause of mortality<br />

in urban and rural populations. Not<br />

to mention diabetes, the prevalence<br />

of which was estimated to be greater<br />

than 31 million in 2005 and growing.<br />

The Consul-General spoke of some of<br />

the health interventions implemented by<br />

the Government to counter this increase<br />

in chronic illness. Recognising that a<br />

centralised approach to health policy<br />

would be less effective, one strategy<br />

has been to empower village councils or<br />

‘Panchayats’, funded by, but not accountable<br />

to, the Government. Composed<br />

of local villagers and an elected leader,<br />

these Panchayats have a better picture of<br />

the cultural and social characteristics of<br />

a region, and are in a position to know<br />

what policies would be most suitable.<br />

Another includes the health education<br />

programs, run by the Central<br />

Health Education Bureau, focusing on<br />

the education of women and children<br />

and taking into account the differences<br />

in beliefs between regions.<br />

These two strategies mentioned by<br />

Mr Dasgupta reiterate that approach<br />

is the key message. Health interventions<br />

need to be tailored and not run<br />

as an identical franchise from state<br />

to state, or as the Consul General put<br />

it, ‘McDonalised’. It comes back to<br />

how we interpret the picture of chronic<br />

disease in India, or in any country;<br />

ensuring the individual characteristics<br />

of that particular picture are what<br />

shape our perceptions and actions. <br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector9<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

The Nageri Mission<br />

Words Jennifer Prince, MS Gen Surgery trainee, CMCH Vellore<br />

Having been in Christian<br />

Medical College<br />

(CMC), a tertiary<br />

hospital throughout<br />

my training, I entered with a<br />

sinking feeling into the Church of<br />

South India (CSI) hospital Nageri,<br />

located on the Andhra Pradesh-<br />

Tamilnadu border in South India.<br />

This was a part of a rural<br />

service obligation. In contrast to<br />

CMC's state-of-the art facilities,<br />

the Nageri hospital was a single<br />

storied building with a minimum<br />

of amenities.. The hospital was<br />

located <strong>10</strong>0km from Chennai, the<br />

capital city of the state of Tamilnadu<br />

and 70km from Tirupati, one<br />

of the large pilgrimage centres of<br />

the neighbouring state of Andhra<br />

Pradesh. It was a cultural potpourri<br />

of the two states yet, development<br />

came slowly to this region.<br />

The hospital itself was conceived<br />

by Dr Fanny Gibbens, a missionary<br />

doctor, and begun in the front yard of<br />

her house. She was in a land of strangers<br />

with just the will to serve the sick.<br />

I find it hard to imagine the depth of<br />

commitment that step would have asked<br />

of her. A new building sprung up as<br />

the workload increased and in a few<br />

years, the hospital reached the zenith of<br />

its development, with long queues of<br />

outpatients stretching into the night and<br />

inpatients awaiting their turn for admission<br />

on the floor between the cots.<br />

But with Dr Gibbens' death the<br />

hospital joined the ranks of Mission<br />

Hospitals started by committed individuals<br />

but struggling to remain open.<br />

The reasons were many- lack of doctors,<br />

paramedical staff, equipment and<br />

a committed leadership. And here<br />

I was, fresh from Internship, full of<br />

hopes, and plans and apprehension.<br />

There was a small medical staff<br />

at the hospital, including the Medical<br />

Superintendent, a Paediatrician, an<br />

auxiliary nurse midwife in charge of<br />

obstetrics and a senior from medical<br />

school. We catered to a patient profile<br />

that varied from those who could not<br />

afford a 5 day course of Amoxycillin for<br />

their children, to affluent businessmen<br />

presenting for follow up between their<br />

regular reviews in private city hospitals.<br />

As the days passed into months, the<br />

other doctors left Nageri and my senior<br />

and I were left to care for the hospital.<br />

As a primary evaluation centre,<br />

the spectrum of cases was wide, from<br />

respiratory infections and viruses to the<br />

common emergencies of traffic accidents<br />

and poisonings. Organophosphorous pesticides<br />

were readily available to the farming<br />

community of Nageri and were the<br />

poison of choice for suicidal attempts.<br />

As we did not have access to monitoring<br />

equipment like an ECG monitor or<br />

a pulse oximeter, or to a ventilator, the<br />

patients were given a gastric lavage and<br />

atropine. If there was any suggestion<br />

of respiratory compromise, the patient<br />

would be intubated and taken<br />

“<br />

by relatives<br />

to the nearest city. What<br />

can I say? It was far from<br />

the ideal in my head;<br />

some made it and some<br />

did not. But occasionally,<br />

we were rewarded<br />

in the form of a patient<br />

who returned for follow up after being<br />

on a ventilator for almost a fortnight.<br />

We did have a functional Operating<br />

Theatre. However, in the absence of<br />

an Anaesthetist, most of the surgeries<br />

we performed were those that could be<br />

done under spinal or local anaesthesia.<br />

On some days, the city hospitals<br />

would oblige us with the services of an<br />

Anaesthetist for more complex cases.<br />

As I mentioned earlier, we had a<br />

section of patients who were from an<br />

affluent background. They often presented<br />

with chronic illnesses such as<br />

Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension and<br />

Obesity. In fact, infected trophic ulcers<br />

constituted one of the most common<br />

as well as dreaded complications of<br />

poorly controlled Diabetes Mellitus<br />

resulting in amputations and numerous<br />

visits for wound care. The patients were<br />

provided advice on lifestyle modification<br />

and were offered the services of<br />

the visiting Physician and an Ophthalmologist<br />

whenever possible.<br />

My favourite part was the weekly<br />

outreach clinic in a selected village<br />

around the hospital, aided by a Non-<br />

Government Organisation. There was<br />

a social worker who supervised four<br />

female workers, each of whom collected<br />

the Health Statistics from areas<br />

around the hospital. Regular Medical and<br />

Ophthalmology camps were a unique<br />

feature of this programme, as well as<br />

health education and preventive medicine.<br />

We worked towards understanding<br />

their beliefs and perceptions on health as<br />

well as addressing some superstitions.<br />

Notable examples of these included<br />

the avoidance of food or water during<br />

diarrhoea or that a febrile illness with<br />

rash was due to divine visitation. These<br />

clinics provided the ideal perspective<br />

of a patient's illness, allowing us to see<br />

firsthand his or her usual environment,<br />

lifestyle and beliefs. I will treasure the<br />

friendships that I have with many of the<br />

families through these interactions.<br />

What did I learn from my experience?<br />

That what mattered most was<br />

that you did the best you could with<br />

the situation rather than looking at the<br />

What can I say? It was far<br />

from the ideal in my head;<br />

some made it and some did not.<br />

”<br />

flaws. I learnt not to take resources for<br />

granted: indeed the hardest problems<br />

were the lack of resources and expertise.<br />

Gloves and sutures were hard to come<br />

by and are to be used carefully. In the<br />

absence of a senior doctor, I learnt to do<br />

what I could in a given situation, often<br />

performing surgical procedures with an<br />

open book for my guide. It did add to<br />

my self confidence and I learnt to rely<br />

on myself in the absence of supervision.<br />

It was also a lesson in administration.<br />

I hope to go back to Nageri after<br />

my General Surgery training. We have<br />

a new administrative team, operations<br />

are being scheduled on a regular basis<br />

and things are indeed looking up. The<br />

Nageri hospital was started with the<br />

vision of service to the ailing. What<br />

this requires is consistent work, vision<br />

and money. Sometimes I question<br />

if one person will be able to make a<br />

difference. But the reality is that there<br />

is often only one person and he/she is<br />

the one who makes the difference. <br />

<strong>10</strong> vector november <strong>2009</strong>

Mental Health Crisis<br />

in China<br />

Words Ron Cheung<br />

Medical student<br />

University of Sydney<br />

// Image by Ringoc2 (sxc.hu)<br />

Mental health is<br />

a substantially<br />

underestimated<br />

problem in China.<br />

In a four province study, 63 000<br />

people were screened in random<br />

urban and rural sites. A trained<br />

psychiatric nurse screened-out<br />

those at high risk of mental illness,<br />

or those with a pre-existing<br />

diagnosis of a severe mental<br />

illness. Those at moderate to low<br />

risk were administered a Chinese<br />

version of the Structured<br />

Clinical Interview for (DSM)-IV<br />

axis I disorders by a psychiatrist.<br />

Importantly, clinicians who<br />

spoke the local dialect and were<br />

familiar with local expressions<br />

and culture were selected, so<br />

they could adapt questions in<br />

order for patients to understand.<br />

Seventeen percent (17%) of the<br />

population had a form of mental illness<br />

(this is 173 million people!). Eleven<br />

percent (11%) of men had issues with<br />

alcohol abuse: an increasing problem<br />

that has thus far not received attention.<br />

Of those with mental illness, 25% were<br />

so severely disabled by it that they<br />

were unable to work. Among all those<br />

with mental illness, only 5% have ever<br />

seen any mental health professional.<br />

Unfortunately, China’s health care<br />

system is plagued by systematic issues.<br />

There are no mental health services in<br />

rural areas. There is a stigma towards<br />

mental illness and even though people<br />

realize they have it, they refuse to seek<br />

treatment. There is a lack of knowledge<br />

- 60% of people interviewed had never<br />

heard of the word depression, even<br />

though they had full blown symptoms.<br />

In China, GP’s do not offer mental<br />

health services, only large psychiatric<br />

wards in large hospitals do<br />

so. It is not seen as part of a GP’s<br />

duties to address mental health.<br />

Closing the gap in mental illness<br />

and services in China is challenging.<br />

The culture of medicine will need to<br />

be changed: barriers will need to be<br />

overcome, medical school curriculums<br />

redeveloped, effective reimbursement<br />

patterns in hospitals introduced, and<br />

the makeup of the health care workforce<br />

that includes a consideration<br />

of the mental health agenda. <br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector11<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

I<br />

was fortunate enough to spend a month of my Christmas<br />

holidays in Papua New Guinea (PNG). The people of PNG have<br />

the lowest health status in the Pacific region. Despite this, life<br />

in PNG is full and the people embrace it with all their might.<br />

I was welcomed with huge smiles and all around kindness. I was<br />

often invited back into people’s homes to meet their families and<br />

be shown their village life.<br />

MEDICINE<br />

and<br />

MOSQUITOES<br />

a medical student’s<br />

month in papua new<br />

guinea<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

One particular day in the town of<br />

Goroka, I was invited to a Christmas<br />

party by the surgical team. For Christmas<br />

the staff often prepare a ‘mumu’, a<br />

traditional way of cooking in PNG where<br />

a whole pig or goat is killed, wrapped in<br />

banana leaves and cooked in the ground<br />

with hot rocks. For this Christmas party<br />

they had decided that they would prepare<br />

a pig for the mumu. So they brought the<br />

pig to the hospital, where it waited on the<br />

first floor balcony until they could kill it<br />

and prepare the mumu. The pig, however,<br />

had other ideas and was last seen<br />

running frantically around the hospital<br />

grounds followed closely by the entire<br />

theatre staff, leaving an empty theatre<br />

and a rather bewildered looking surgeon.<br />

I was later informed that pigs are highly<br />

valued in PNG and are a symbol of<br />

wealth and social standing. In fact they<br />

12 vector november <strong>2009</strong><br />

are so important that women will often<br />

breastfeed the piglets when they are born.<br />

Now after they had caught the pig<br />

and it was prepared for the mumu I sat<br />

down with the theatre staff and surgical<br />

team to enjoy the feast. However, this<br />

was not for long as the surgical resident<br />

and myself were called to emergency to<br />

assess a patient. Having been in PNG for<br />

over 3 weeks I was not easily shocked<br />

by anything I saw, but this still did shock<br />

me! On entering the ED I was directed<br />

to a young man sitting on the edge of a<br />

bed with three arrows protruding from<br />

his body. He had been shot four times<br />

in total; the first arrow was in the ninth<br />

intercostal space on the left, the second<br />

entered the superficial tissue on his right<br />

flank, the third was embedded in his<br />

groin and the fourth he had removed<br />

himself from his right triceps. Despite<br />

Words and Photos<br />

Georgia Ritchie<br />

Medical student<br />

University of Sydney<br />

the wounds, he sat perfectly still and<br />

appeared not to be in any pain. Despite<br />

much effort the radiographer at the hospital<br />

could not be contacted that evening<br />

so the young man had to wait until morning<br />

for his X-rays and surgery to remove<br />

the arrows. This meant he had to sleep<br />

on his front with three arrows protruding<br />

form his body! When he eventually went<br />

to surgery, it was found that the arrow<br />

entering the chest had passed through the<br />

spleen, the duodenum and the transverse<br />

colon. After 7 hours of surgery, the arrow<br />

was removed, the spleen saved and the<br />

puncture wounds to the bowls closed and<br />

he was sent to the ward for recovery.<br />

I have a story about each day I<br />

spent in PNG. Whether it is about the<br />

amazing people I met or the interesting<br />

medical cases I saw, I was constantly<br />

in awe of the country. Although<br />

at times a hard place to comprehend,<br />

I feel that I understood by the end<br />

of my trip and fell in love with the<br />

PNG, its culture and the people.

Stories from<br />

Cambodia<br />

Behind these smiles are stories of great<br />

sadness and tragedy<br />

Words and Photos Nilru Vitharana<br />

Medical student, University of Sydney<br />

During my summer<br />

holidays last year, I<br />

spent a few weeks<br />

volunteering at an<br />

orphanage and medical clinic in<br />

rural Cambodia in a town called<br />

Neak Leung on the banks of the<br />

Mekong River. Cambodia has<br />

some of the worst health statistics<br />

in the world – 1 in 7 children<br />

will die before the age of 5.<br />

The charity I visited was called<br />

Damnok Toek, which means ‘a drop<br />

of water’ in Khmer. Ironic, given<br />

that the area is surrounded by flooded<br />

rice paddy fields, and the houses<br />

are built up on stilts to avoid the<br />

floodwaters during rainy season.<br />

Damnok Toek houses 60 orphans,<br />

provides schooling for a further 150<br />

children and has a social work program<br />

and medical clinic. As you can see<br />

from the photos, the children here are<br />

all smiles, but behind these smiles are<br />

stories of great sadness and tragedy.<br />

Some of the children in the permanent<br />

centre had been sold into child<br />

prostitution and child labour in Thailand’s<br />

notorious Pattaya district before<br />

they were rescued, some are AIDS<br />

orphans, some are mentally or physically<br />

handicapped and thus abandoned<br />

by their families who cannot afford<br />

to take care of them, and others were<br />

the victims of domestic violence.<br />

The medical clinic here provides a<br />

vital service for the rural poor. The government<br />

healthcare system is expensive<br />

($20 US for a consultation) and underresourced.<br />

The poor,<br />

many of whom earn<br />

less than $1 a day,<br />

simply cannot afford<br />

it. In contrast, the<br />

medical clinic costs<br />

12 cents (including<br />

medication). People<br />

would travel several<br />

hours to receive affordable<br />

medical care.<br />

I also spent much<br />

of my time doing<br />

social work in the<br />

community. One day we went to followup<br />

a child who hadn’t been turning up<br />

to school, which surprised us because he<br />

loved going to school and hadn’t missed<br />

a day. When we arrived at his home we<br />

discovered that his older brother had died<br />

of AIDS, and now he had to stay at home<br />

to take care of his younger brother. Stories<br />

like his are a prime example of the<br />

“cycle of poverty” – now he is likely to<br />

miss out on the opportunity of education.<br />

Living with a local family, I was<br />

able to immerse myself in the language<br />

and culture of the Khmer<br />

people. Having fallen in love with the<br />

people of Cambodia, I will be returning<br />

this year to Damnok Toek. <br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector13<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

global health<br />

in the news<br />

Copenhagen Climate Change<br />

Summit will be held in December<br />

<strong>2009</strong>. For the health impacts<br />

of climate change, refer<br />

to the editorial published by the<br />

Lancet and BMJ and University<br />

College London in September<br />

<strong>2009</strong>.<br />

http://en.cop15.dk<br />

World Diabetes Day<br />

14th November <strong>2009</strong><br />

WHO estimates that more than 180 million people worldwide have diabetes,<br />

according to 2005 figures. This number is likely to more than double by<br />

2030 without intervention. Almost 80% of diabetes deaths occur in low and<br />

middle-income countries.<br />

www.worlddiabetesday.org<br />

HIV vaccine?<br />

A trial of a vaccine to prevent infection<br />

by HIV involving 16,000 participants<br />

in Thailand this year has shown modest<br />

results with 26% reduction in rates of<br />

infection compared to placebo controls.<br />

Refer to the October 20th <strong>2009</strong> issue of<br />

the New England Journal of Medicine.<br />

PNG’s Liquid Nitrogen Gas<br />

(LNG) Project will officially open<br />

in 20<strong>10</strong>, is expected to double the<br />

country’s GDP, and will have a profound<br />

impact on trade and health<br />

in the Pacific region. Refer to a<br />

series by Jo Chandler of The Age<br />

published September this year.<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

Indonesia’s official death toll stands<br />

at 650, with a 672 people missing, following<br />

the devastation of the recent<br />

earthquake. Damage to roads, disruption<br />

to electrical power and sources of clean<br />

water could make the situation much<br />

worse in the coming weeks.<br />

There is similar concern in Samoa<br />

about the spread of infectious diseases,<br />

such as causes of acute watery diarrhoea,<br />

typhoid fever and dengue fever<br />

following the Tsunami.<br />

2nd November <strong>2009</strong> commemorates renewed efforts to promote pneumonia<br />

on the global health agenda by 2011. Wear blue jeans on the 2nd of November<br />

(signifying the 2 million deaths of children every year due to pneumonia) and support<br />

this cause.<br />

www.worldpneumoniaday.org<br />

14 vector november <strong>2009</strong>

global health network<br />

update<br />

Welcome to the GHN<br />

A Year in the GHN:<br />

Looking back and<br />

looking forwards<br />

Trung Nghia Ton<br />

WakeUp! GHN Officer, University of Newcastle<br />

AMSA GHN Chair <strong>2009</strong> - 20<strong>10</strong><br />

Tamara Vu<br />

AMSA GHN Chair<br />

2008-09<br />

A very warm<br />

welcome to you all on<br />

behalf of the AMSA<br />

Global Health Network<br />

Committee! This issue<br />

of <strong>Vector</strong> marks the start of yet another<br />

Global Health Calendar year (kicked off by<br />

a truly rousing Global Health Conference in<br />

Brisbane).<br />

We look forward to adding to the<br />

monumental efforts of the GHN Committee<br />

of 08/09 who have worked tirelessly to bring<br />

together students from all over the country<br />

to collaborate in common interests in global<br />

health awareness and action. This culminated<br />

in the very first GHN National project, the<br />

Red Party concept, which raised national<br />

funds and awareness for HIV/AIDS, and was<br />

a huge success. This is a tangible example of<br />

how our efforts at a local level can be part<br />

of a global impact. Additionally, The GHN<br />

began its first national advocacy movements,<br />

further highlighting the GHN’s increasing<br />

ability to inform, represent and advocate for<br />

medical students in matters of global health.<br />

I would like to extend heartfelt congratulations<br />

and thanks to the outgoing<br />

GHN Committee for their successes this last<br />

12 months. It is without a doubt that their<br />

efforts have made a real and tangible difference,<br />

and has set up a national framework<br />

for us to continue to grow and mature as an<br />

organisation. Their efforts continue to reflect<br />

on the new committee as they mentor us<br />

through a very steep learning curve.<br />

With much enthusiasm, the newly<br />

elected GHN committee for 09/<strong>10</strong> are getting<br />

right onto the task. Realising this year’s GHN<br />

National project, the South East Asian Libraries<br />

Project, will be a challenging undertaking<br />

but with the experience and motivation of<br />

each global health group (GHG) we hope to<br />

exploit the growing momentum and make<br />

a longstanding impact by helping our fellow<br />

medicos in the developing world (watch this<br />

space!). We also hope to strengthen our<br />

collective voices and to bring truly pressing<br />

global health advocacy issues to the fore in<br />

our chosen active advocacy campaigns, especially<br />

in regards to the crucial Millennium<br />

Development Goals, and the treatment of<br />

refugees and asylum seekers.<br />

The GHN remains an avenue for medical<br />

students to bring ideas, issues and action to<br />

a national level, but it is vitally important for<br />

us all to look at developing our own Global<br />

Health Groups (GHG) and individual initiatives<br />

– there are so many opportunities available<br />

to bring grass roots ideas and projects to<br />

fruition and collaborate on a local, regional<br />

and national level.<br />

I invite you all to become active members<br />

of your local GHG as they grow into dynamic<br />

student organisations. It is incredibly exciting<br />

to see the initiatives of GHGs around the<br />

country in 09/<strong>10</strong> and I look forward to working<br />

with an exceptional and motivated GHN<br />

Committee and witness medical students<br />

making a real difference in our global community.<br />

As the outgoing<br />

Chair of the Global<br />

Health Network (GHN),<br />

I am delighted to<br />

report on our successful<br />

year of global health group development<br />

and support; our wildly successful National<br />

Project, the Red Party, which raised over<br />

$88 022 for HIV/AIDS support and research;<br />

and our advocacy working party, which<br />

developed the Millennium Development<br />

Goals policy that in February became<br />

AMSA’s first-ever global health-based policy<br />

document.<br />

It’s been a great year for medical<br />

students in global health, with new and<br />

exciting work happening in global health<br />

groups, in the GHN, at GHC09, and at AMSA<br />

level. It has been my privilege to serve as<br />

GHN Chair during the last twelve months.<br />

Along with the other outgoing GHN Representatives<br />

and officers, I am delighted to be<br />

handing over the reigns to a new committee,<br />

as I know Trung and his team will be<br />

dedicated and enthusiastic in promoting<br />

and supporting global health activities<br />

around Australia. And, looking back on the<br />

various global health events of the past<br />

year, I look forward to seeing what the next<br />

twelve months will bring.<br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector15<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

The Global Health Conference:<br />

Challenging the world after Brisbane<br />

Meg Scott Deputy Convenor GHC <strong>2009</strong><br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

As I think back over the 4 days of the<br />

Global Health Conference <strong>2009</strong> (GHC),<br />

certain events and lessons I learned remind<br />

me to do more with my life and challenge my<br />

world!<br />

Our biggest achievement, the event we<br />

put the most blood, sweat and tears into<br />

was challenge day. The <strong>10</strong> station, half-day<br />

workshop challenged the delegates to work<br />

through various situations one might come<br />

up against in an overseas medical aid situation.<br />

Delegates planned a refugee camp and<br />

were marked on the appropriateness of their<br />

toilet selection, as well as deciding how many<br />

farms they would have. Groups got to try<br />

talking their way into a prisoner of war camp<br />

past cheeky guards, and the guards were<br />

also marked on their ability to stick to their<br />

guns. The triage station allowed the clinical<br />

years delegates to shine, using their ability<br />

to interpret vital signs to save many a paper<br />

doll life. We made nutritional food packs, delivered<br />

babies (and placentas) in emergency<br />

situations, learned about the difficulties in<br />

communicating with non-English speaking<br />

patients, allocated sparse resources to those<br />

who needed it the most, and perhaps most<br />

importantly, enjoyed the Brisbane sunshine!<br />

The inspiring opening plenary from Dr.<br />

Sujit taught me a couple of things. One, if<br />

you want to add prestige to a product, print<br />

the label in English; if the people can’t read<br />

it, they’ll want it more. Two, having nothing<br />

is no excuse; start where you are and<br />

the financial support will come. There is no<br />

reason why one person can’t start making<br />

a difference in the community. Personally,<br />

I was amazed at how easy Dr. Sujit made it<br />

all sound! Starting at a farm, negotiating the<br />

use of a barn for a clinic, to shortly thereafter<br />

running numerous hospitals and schools! He<br />

definitely challenged my idea that one needs<br />

money to make a difference.<br />

Tania Major continued the unintended<br />

theme to get out there and start doing, with<br />

her challenging Australians’ attitudes towards<br />

the Indigenous population. She spoke of her<br />

work increasing awareness of Indigenous<br />

issues, which she has been doing for the<br />

majority of her life. She reminded us that<br />

whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous, we<br />

are all Australian, and we must look after<br />

our own. We all know of the 17 year age<br />

gap between the two populations, and the<br />

barriers towards proper healthcare for those<br />

in remote communities are not new. Tania<br />

showed us that grassroots action is vital in<br />

making a change. As Tania so eloquently<br />

stated, “just fucking do it!”<br />

Carolyn Hardy showed us what has been<br />

done so far in combating HIV/AIDS, and we<br />

are sadly nowhere near meeting the Millennium<br />

Development Goal. Again we were<br />

shown how to challenge the problems in<br />

bringing healthcare to those who need it,<br />

and how to overcome these obstacles. Carolyn<br />

spoke of the potential for conducting HIV<br />

tests remotely via mobile phone and picture<br />

texts! With unbelievable solutions like this<br />

in the works, I was reminded to look outside<br />

the box for solutions to decade-old problems.<br />

Dr. Nick Coatsworth gave me wanderlust<br />

recounting his missions with MSF to such<br />

places as Darfur and the Sudan. He also<br />

spoke of getting in there and working at a<br />

grassroots level and somehow managed to<br />

make immunising hundreds of children a day<br />

for 4 weeks straight sound exciting! He’s definitely<br />

an inspiration for all medical students,<br />

showing us that it is possible to have a life,<br />

train in a specialty and work overseas all at<br />

once.<br />

Gabi Hollows, on behalf of the Fred<br />

Hollows Foundation (FHF), taught us that<br />

enthusiasm is enough; that having passion<br />

for a cause will make things happen. She<br />

also reminded us of the need for medical<br />

aid in Australia. Sure, while the FHF now<br />

have clinics and factories all over the world,<br />

Fred Hollows’ work started in rural/remote<br />

Australia, and Gabi reminded us we cannot<br />

overlook our own country. Also, what struck<br />

me from the Fred Hollows story was that one<br />

persons’ passion and hard work can continue<br />

indefinitely.<br />

After all that energy spent learning<br />

and inspiring, I wouldn’t have<br />

thought anyone had enough energy<br />

for a party, but boy, was I wrong!<br />

Perhaps the memory burned into my<br />

mind the most was the monkey dancing<br />

with the genie, or was it seeing 2<br />

sumo wrestlers trying to get onto a<br />

bus? Check out the pictures on our<br />

website to decide for yourself…<br />

Thank you everyone for coming<br />

to Brisbane, for participating so fully<br />

in the program (both day and night!),<br />

and for challenging yourself and your<br />

peers to do more and be more. I look<br />

forward to seeing you in Hobart for<br />

GHC 20<strong>10</strong> and hearing about how you<br />

have challenged your world this year.<br />

Left: The GHC is a ‘hands-on’ event.<br />

Far left and above left: Dr Sujit inspires<br />

the audience to make a difference. Images:<br />

www.amsa.org.au/ghc09<br />

16 vector november <strong>2009</strong>

Student Involvement<br />

Helping VSAP to help others<br />

What is VSAP?<br />

The Victorian Students’ Aid Program<br />

(VSAP) is a student initiative run by medical<br />

students at the University of Melbourne,<br />

which delivers much needed equipment and<br />

health resources to disadvantaged communities<br />

globally.<br />

Our vision is that all doctors worldwide<br />

will have essential medical supplies and<br />

equipment to treat their patients.<br />

Recently, VSAP has elected to broaden its<br />

scope and fulfil the role of being the University<br />

of Melbourne’s global health group. This<br />

financial year we will be taking on additional<br />

projects as well as expanding into the areas<br />

of education and advocacy.<br />

Check out our website for more information<br />

on: our Teddy Bear Hospital community<br />

project, our Global Health Short Course being<br />

held in collaboration with the Nossal Institute<br />

for Global Health, and our Red Party fundraising<br />

event that raises money for HIV/AIDS<br />

research and awareness. One of our main,<br />

ongoing projects is the Wishlist Project.<br />

What is the Wishlist Project?<br />

The Wishlist Project aims to contribute<br />

to global health equity by sending<br />

targeted aid to hospitals in<br />

poorly resourced areas via medical<br />

students completing their elective<br />

placements there.<br />

To ensure that we are supplying<br />

appropriate and effective<br />

equipment, the hospitals are asked<br />

to compile a ‘wishlist’ of the supplies<br />

and equipment that they require.<br />

VSAP works with hospitals and medical<br />

suppliers in Australia to fulfil these wishlists<br />

and these donations are delivered with the<br />

medical student when they leave for their<br />

elective placement.<br />

Since its inception in 2005, VSAP has<br />

delivered over $30000 worth of equipment<br />

and monetary donations to countries as<br />

diverse as Guatemala, Tanzania, East Timor<br />

and Vietnam.<br />

How can you be involved?<br />

Student involvement – Helping VSAP to help<br />

others<br />

We are always looking for travelling<br />

students who can deliver donated supplies to<br />

areas where health care professionals are in<br />

need of medical supplies. We are also looking<br />

for students to get involved in our various<br />

projects. Please contact us by email.<br />

Equipment and financial contributions for<br />

Wishlists<br />

VSAP relies on the generosity of sponsors<br />

to obtain equipment to send to underresourced<br />

communities. In the past, health<br />

institutions have been the main contributors<br />

of equipment particularly when they reorganise,<br />

close down, have excess supplies,<br />

or upgrade.<br />

VSAP is also responsible for the logistics<br />

of delivering donated supplies to destination<br />

hospitals. Assistance with airfreight,<br />

packaging, and transport would also be very<br />

welcome.<br />

We are always looking for sponsors of<br />

medical equipment and supplies. If you<br />

would like to donate, please contact us by<br />

email.<br />

Contact us<br />

General enquiries:<br />

vsap.aid@gmail.com<br />

Sponsorship enquiries:<br />

vsap.sponsorship@gmail.com<br />

For more information, visit http://www.<br />

vsap.org.au<br />

Right: Sanka Amadoru delivering<br />

supplies to Kibosho Hospital, Tanzania.<br />

Far right: Alexandra Bryson<br />

using a donated anaesthetic machine,<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Global Health Lecture Series - The University of Sydney<br />

Nilru Vitharana, Acting Chair, USyd GlobalHOME [Global Health Group]<br />

After attending the Global Health Conference, students from<br />

globalHOME (Sydney University’s global health group) were inspired<br />

to educate their fellow students about global health by developing<br />

a lecture series to improve the global health awareness and skills of<br />

medical students.<br />

The 8-part lecture series will be delivered by leading experts<br />

in the field, from doctors, public health personnel, and NGOs. The<br />

topics to be covered include: aid and poverty, healthcare in conflict<br />

settings, emergency response to natural disasters, tropical infectious<br />

diseases, climate change and its impact on health, malnutrition and<br />

indigenous health. This series will equip students with the necessary<br />

clinical and public health skills to understand global health issues<br />

that they may encounter whilst on elective or in their future careers.<br />

The lecture series will feature case studies, scenarios, interactive<br />

discussion and is designed to appeal to students from across all<br />

years of the medical program. The lectures will be held on Tuesday<br />

evenings in March and May. Students from other universities are<br />

most welcome to attend. Please sign up to our Yahoo Group (http://<br />

groups.yahoo.com/group/globalhome/) to join our mailing list and<br />

keep up to date with details of our lecture series.<br />

november <strong>2009</strong> vector17<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au

creative<br />

pieces<br />

www.ghn.amsa.org.au<br />

“It was in the news. He<br />

jumped off the bridge last<br />

qweek. He died.” My old<br />

school friend told me in<br />

tears on the phone. The sunlight<br />

is so bright. I sit, feeling a little<br />

nauseous. In that country, it is<br />

the coldest time of the year. Did<br />

he drown or freeze to death?<br />

“Does anyone know why he killed<br />

himself?” We used to go to the same<br />

primary school. We were in the same<br />

class although he was 3 years older<br />

than the rest of the class. Kids used to<br />

laugh at him, because his legs looked<br />

funny. He had poliomyelitis. He would<br />

never catch anyone after being teased. It<br />

would only cause more laughs. And he<br />

walked in the most awkward way, too.<br />

“They said he was a psycho, he went<br />

to see a shrink a few times.” The last<br />

time I heard about him was last year.<br />

He published an article on a famous<br />

magazine, named “A sad river”. I can<br />

just remember the words he used in<br />

that book. That unbearable sense of<br />

sorrow floods my heart even now.<br />

“Was he depressed?” He never really<br />

spoke to anyone. I supposed we were<br />

all immature and didn’t want to hang<br />

out with a kid who couldn’t play with<br />

us. He dropped out of school after high<br />

school. It was simply too far away. His<br />