Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

page 2<br />

Mae Tao Clinic School Health Program<br />

Ying Ying Liew<br />

In December 2006 I decided to<br />

volunteer as a medical student for a<br />

month in Mae Tao clinic in Northern<br />

Thailand. It is a clinic founded by a<br />

Karen refugee, Dr Cynthia Maung<br />

who fled Burma after the 1988<br />

student uprising. For almost 20 years<br />

now, this clinic has been providing<br />

much needed free health care services<br />

for displaced people on the Thai-<br />

Burma border. As a consequence of<br />

nearly 50 years of rule by military<br />

dictatorship and civil war, hundreds<br />

and thousands of people from Burma<br />

especially those living close to the<br />

border have been victims of forced<br />

relocation, which has led many to<br />

flee into nearby jungle or neighbouring<br />

countries like Thailand for<br />

refuge. The Mae Tao clinic is mainly<br />

run by ethnic minoritiesʼ refugees<br />

and the health workers are locally<br />

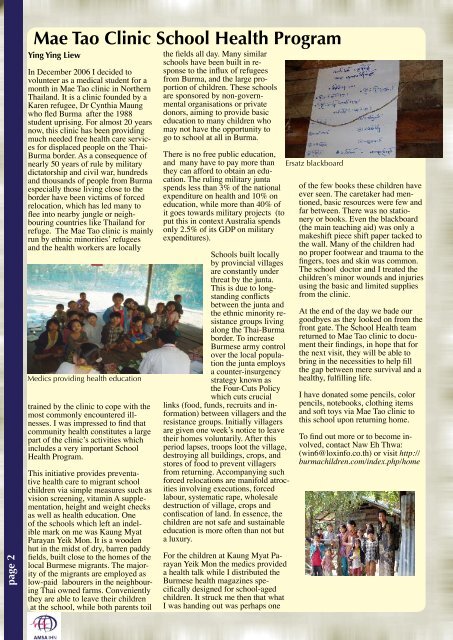

Medics providing health education<br />

trained by the clinic to cope with the<br />

most commonly encountered illnesses.<br />

I was impressed to find that<br />

community health constitutes a large<br />

part of the clinicʼs activities which<br />

includes a very important School<br />

Health Program.<br />

This initiative provides preventative<br />

health care to migrant school<br />

children via simple measures such as<br />

vision screening, vitamin A supplementation,<br />

height and weight checks<br />

as well as health education. One<br />

of the schools which left an indelible<br />

mark on me was Kaung Myat<br />

Parayan Yeik Mon. It is a wooden<br />

hut in the midst of dry, barren paddy<br />

fields, built close to the homes of the<br />

local Burmese migrants. The majority<br />

of the migrants are employed as<br />

low-paid labourers in the neighbouring<br />

Thai owned farms. Conveniently<br />

they are able to leave their children<br />

at the school, while both parents toil<br />

the fields all day. Many similar<br />

schools have been built in response<br />

to the influx of refugees<br />

from Burma, and the large proportion<br />

of children. These schools<br />

are sponsored by non-governmental<br />

organisations or private<br />

donors, aiming to provide basic<br />

education to many children who<br />

may not have the opportunity to<br />

go to school at all in Burma.<br />

There is no free public education,<br />

and many have to pay more than<br />

they can afford to obtain an education.<br />

The ruling military junta<br />

spends less than 3% of the national<br />

expenditure on health and 10% on<br />

education, while more than 40% of<br />

it goes towards military projects (to<br />

put this in context Australia spends<br />

only 2.5% of its GDP on military<br />

expenditures).<br />

Schools built locally<br />

by provincial villages<br />

are constantly under<br />

threat by the junta.<br />

This is due to longstanding<br />

conflicts<br />

between the junta and<br />

the ethnic minority resistance<br />

groups living<br />

along the Thai-Burma<br />

border. To increase<br />

Burmese army control<br />

over the local population<br />

the junta employs<br />

a counter-insurgency<br />

strategy known as<br />

the Four-Cuts Policy<br />

which cuts crucial<br />

links (food, funds, recruits and information)<br />

between villagers and the<br />

resistance groups. Initially villagers<br />

are given one weekʼs notice to leave<br />

their homes voluntarily. After this<br />

period lapses, troops loot the village,<br />

destroying all buildings, crops, and<br />

stores of food to prevent villagers<br />

from returning. Accompanying such<br />

forced relocations are manifold atrocities<br />

involving executions, forced<br />

labour, systematic rape, wholesale<br />

destruction of village, crops and<br />

confiscation of land. In essence, the<br />

children are not safe and sustainable<br />

education is more often than not but<br />

a luxury.<br />

For the children at Kaung Myat Parayan<br />

Yeik Mon the medics provided<br />

a health talk while I distributed the<br />

Burmese health magazines specifically<br />

designed for school-aged<br />

children. It struck me then that what<br />

I was handing out was perhaps one<br />

Ersatz blackboard<br />

of the few books these children have<br />

ever seen. The caretaker had mentioned,<br />

basic resources were few and<br />

far between. There was no stationery<br />

or books. Even the blackboard<br />

(the main teaching aid) was only a<br />

makeshift piece shift paper tacked to<br />

the wall. Many of the children had<br />

no proper footwear and trauma to the<br />

fingers, toes and skin was common.<br />

The school doctor and I treated the<br />

childrenʼs minor wounds and injuries<br />

using the basic and limited supplies<br />

from the clinic.<br />

At the end of the day we bade our<br />

goodbyes as they looked on from the<br />

front gate. The School Health team<br />

returned to Mae Tao clinic to document<br />

their findings, in hope that for<br />

the next visit, they will be able to<br />

bring in the necessities to help fill<br />

the gap between mere survival and a<br />

healthy, fulfilling life.<br />

I have donated some pencils, color<br />

pencils, notebooks, clothing items<br />

and soft toys via Mae Tao clinic to<br />

this school upon returning home.<br />

To find out more or to become involved,<br />

contact Naw Eh Thwa:<br />

(win6@loxinfo.co.th) or visit http://<br />

burmachildren.com/index.php/home