Winter 2023

Restoration Conversations is a digital magazine spotlighting the achievements of women in history and today. We produce two issues a year: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter

Restoration Conversations is a digital magazine spotlighting the achievements of women in history and today. We produce two issues a year: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

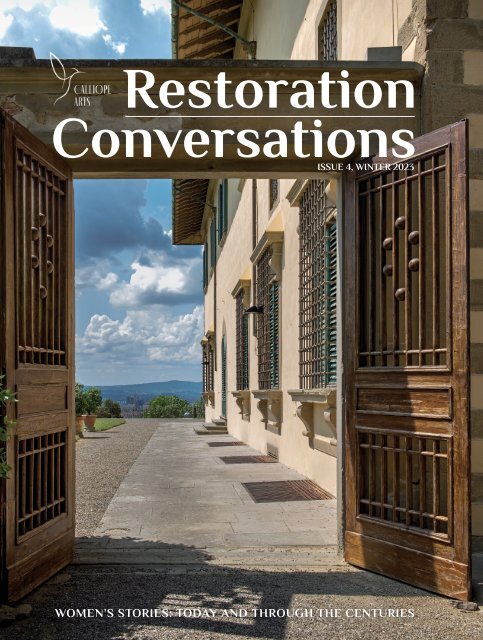

Restoration<br />

Conversations<br />

ISSUE 4, WINTER <strong>2023</strong><br />

WOMEN’S STORIES: TODAY AND THROUGH THE CENTURIES<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 1

Publisher<br />

Calliope Arts Foundation<br />

London, UK<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Linda Falcone<br />

Contributing Editor<br />

Margie MacKinnon<br />

Design<br />

Fiona Richards<br />

FPE Media Ltd<br />

Video maker for RC broadcasts<br />

Francesco Cacchiani<br />

Bunker Film<br />

www.calliopearts.org<br />

@calliopearts_restoration<br />

Calliope Arts<br />

2 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

From the Editor<br />

Today’s women, featured in this issue of Restoration Conversations, have done<br />

their share of searching, and that may well be the reason they find themselves<br />

pictured between these pages. Violinist Ruth Palmer and scholar Claudia Tobin<br />

seek – through their research and performance – to bring female composers and<br />

poetic-minded ‘freedom fighters’ to the fore. In her new book Women at Work<br />

from 1900 to Now, author and curator Flavia Frigeri leaves no field of female<br />

achievement unexplored. Conservator Eugenia Di Rocco strives to safeguard the<br />

Wulz sisters’ iconic images from Alinari Foundation for Photography – because<br />

photography can vanish, if not painstakingly protected, and English painter Cecily<br />

Brown seeks to translate the silent tribulations of a third-century saint into a<br />

language called ‘colour’ at Florence’s Museo Novecento.<br />

These women, and others found herein, perform, safeguard, uncover and share the<br />

achievements of their historic counterparts: Ethyl Smyth’s The March of Women,<br />

Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba, Maryla Lednicka-Szczytt’s Black Angel. Their<br />

stories are more relevant than ever. So, there’s reason to celebrate in the new year,<br />

not least because Artemisia’s censored allegory has her legs back (digitally) and is<br />

using them to get to her Genoa show come 2024!<br />

Fondly,<br />

Linda Falcone<br />

Managing Editor, Restoration Conversations<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 3

GRAZIE MILLE<br />

As the conversation around women’s achievements grows, we have more<br />

and more people to thank with every issue of the magazine. Not that we are<br />

complaining! It is wonderful to see this community expanding. Massive thanks to<br />

the people whose words fill these pages:<br />

Virtuosic violinist Ruth Palmer; curator, academic and author Claudia Tobin; Director<br />

of the Alinari Phototography Foundation Claudia Baroncini; members of the 5,000<br />

Negatives team Eugenia Di Rocco and Pamela Ferrari; National Gallery (London)<br />

curator Priyesh Mistry; Museo Novecento’s artistic director and curator Sergio Risaliti;<br />

National Gallery of Ireland’s curator Aoife Brady and conservator Maria Canavan; art<br />

historian and dean emerita of the National Gallery (Washington) Elizabeth Cropper;<br />

Towards Modernity co-curator Ilaria Sgarbozzo; Consuelo Lollobrigida, professor<br />

and art historian; the Opificio delle pietre dure’s senior paper conservator, Simona<br />

Calza; and Costantino D’Orazio, art historian and curator of Artemisia Gentileschi,<br />

Courage and Passion at the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa.<br />

Thank you to all who enthusiastically participated in the ‘Palace Women’ project<br />

as artisans, photographers, tour guides, educators and otherwise, with special<br />

mention to institutional partners the British Institute in Florence and Il Palmerino<br />

Cultural Association, as well as co-sponsors Alice Vogler and Donna Malin.<br />

With the exhibition Artemisia in the Museum of Michelangelo drawing to a close,<br />

we would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to ‘Artemisia UpClose’ co-sponsor<br />

Christian Levett and to Casa Buonarroti’s Museum Director Alessandro Cecchi<br />

and Foundation President Cristina Acidini. Grazie mille also to designer Massimo<br />

Chimenti and his team at Culturanuova for creating the perfect showpiece for our<br />

‘Artemisia UpClose’ project. We are delighted that part of this exhibition will carry<br />

on in Genoa.<br />

4 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

CONTENTS WINTER <strong>2023</strong><br />

MUSIC AND A VOICE<br />

6 Close Encounters<br />

14 The Words We’d Like to Meet<br />

20 Notable Women<br />

24 You Oughta Be In Pictures<br />

AT WORK IN HISTORY<br />

32 Palace Women Find Common Ground<br />

36 5,000 Negatives<br />

42 Time Travel at Florence’s Opificio<br />

48 The Big Reveal<br />

54 Three Wishes<br />

58 Mission Accomplished<br />

FORERUNNERS PRESS FORWARD<br />

62 Trailblazer, Rule Breaker<br />

68 The Star of the Show<br />

74 Courage and Passion<br />

WOMEN INSPIRED<br />

80 The Colour is Brown<br />

86 The Painting in the Dining Room<br />

92 Women at Work<br />

98 Two New Books<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 5

Close<br />

Encounters<br />

A conversation with violinist Ruth Palmer<br />

Let’s begin at the end. The last work in the<br />

programme for ‘Scoring Suffrage’, a recital<br />

of music by women composers held at<br />

the Lyceum in Florence in September,<br />

was ‘Piece for Ruth’, by Venezuelan<br />

pianist and composer Gabriela Montero.<br />

The ‘Ruth’ in question is Ruth Palmer,<br />

the acclaimed violinist, and one half of<br />

‘Scoring Suffrage’s’ creative team, with<br />

whom I was now having a coffee at the<br />

Hayward Gallery on London’s South<br />

Bank. I asked her if any one of the pieces<br />

in the recital was more challenging than<br />

the others. “They all have their own<br />

challenges in different ways,” she said.<br />

For example, “the Montero has one tricky<br />

bit, but it was written for me, so I can<br />

do what I want with it.” Had she known<br />

that Montero was going to write it for<br />

her? “I asked her to write it for me,” she<br />

replied, and proceeded to recount the<br />

improbable story of their initial meeting.<br />

“I used to live not far from here on<br />

Fleet Street,” Ruth recalled. “One day,<br />

as I was crossing the road to go to the<br />

stationer’s, I was hit by a scooter that<br />

sent me literally flying horizontally<br />

over the bus lane.” The scooter driver,<br />

Richard, had been in a terrible hurry to<br />

get somewhere and had filtered down<br />

the wrong side of the road. Luckily, Ruth<br />

was fine but for a few scratches. As it<br />

happened, a police officer had witnessed<br />

the accident and asked if she wanted<br />

to press charges. Ruth declined, saying<br />

she wouldn’t press charges so long as<br />

6 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Richard agreed to come to her next Wigmore<br />

Hall recital. And even though he didn’t attend the<br />

recital, the two stayed in touch.<br />

Some two years later, Richard’s brother Sam<br />

wrote to Ruth, hoping to speak to her about a<br />

project he had been thinking about. He had<br />

seen In Search of the Messiah, a film in which<br />

Ruth starred as a violinist seeking out the world’s<br />

most prestigious violins, which had aired on arts<br />

networks throughout the world. “He was quite<br />

excited about it,” explained Ruth, “and wanted to<br />

discuss some ideas he had for his own project.”<br />

Ruth told Sam the conversation would have to<br />

wait, as she was on her way to visit her cousin in<br />

Lexington, Massachusetts.<br />

No problem, Sam replied. As it happens, I am<br />

going to Lexington myself. “And it turned out<br />

that he was living with Gabriela Montero around<br />

the corner from my cousin. So, I met her in her<br />

kitchen eating pumpkin pie. We got talking and<br />

eventually I said, ‘Will you write me a piece?’ She<br />

agreed, and we played it together a year later, in<br />

New York.”<br />

Earlier that morning, Ruth and I met to check<br />

out a venue for a reprise of ‘Scoring Suffrage’<br />

in London. Our destination was the 1901 Arts<br />

Club, a rehearsal and performance space created<br />

by philanthropist, conductor and violinist Joji<br />

Hattori. (As a young violinist Ruth won a Hattori<br />

Foundation prize which, in a further coincidence,<br />

was presented to her by the person who had<br />

recommended the 1901 Arts Club to me – a friend<br />

I met while we were both walking our dogs on<br />

Hampstead Heath.) The club occupies a lovingly<br />

restored schoolmaster’s residence in a street of<br />

small Victorian terraced houses and is decorated<br />

Above: Ruth Palmer in ‘Scoring<br />

Suffrage’ at Florence’s Lyceum.<br />

Photo by Marco Berni<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 7

Below: Ruth Palmer and<br />

pianist Alessio Enea in ‘Scoring<br />

Suffrage’ at Florence’s Lyceum.<br />

Photo by Marco Berni<br />

in the style of a European Salon. Its intimate<br />

size and salon-like atmosphere seem ideal for<br />

the nineteenth and early twentieth-century<br />

repertoire of ‘Scoring Suffrage’. Ruth had brought<br />

her violin with her and set about testing the<br />

space’s acoustics. We were soon rolling up two<br />

rugs on the original wooden floor and pulling<br />

back a heavy curtain behind the grand piano.<br />

After another sound check, Ruth seemed satisfied<br />

with the result, although the improvement in<br />

resonance was lost on my untrained ears.<br />

‘Scoring Suffrage’ was conceived not solely as<br />

a musical event, rather, it is a weaving together<br />

of the music, literature and personal stories of<br />

women whose lives and careers overlapped<br />

with women’s suffrage movements in Europe.<br />

Through the narration of letters, poetry and other<br />

writings, Ruth’s partner in this project, curator and<br />

academic Dr Claudia Tobin (see feature on p. 14),<br />

provides the context in which woman composers<br />

were working and creating the soundtrack that<br />

accompanied women’s growing political and<br />

expressive freedom. The third member of the<br />

team was London-based pianist Alessio Enea,<br />

who accompanied Ruth in the performance.<br />

On this day in the Hayward’s cafe, we would<br />

talk about the works of the six female composers<br />

featured in ‘Scoring Suffrage’: Fanny Mendelssohn<br />

(1805-1847), Clara Schumann (1819-1896), Ethel<br />

Smyth (1858-1944), Lili Boulanger (1893-1918),<br />

Florence Price (1887-1953) and Gabriela Montero<br />

(b. 1970). A single male composer, Maurice Ravel<br />

(1875-1937), made it on to the programme by virtue<br />

of the significance of two women to his work.<br />

The first piece in the programme was Fanny<br />

Mendelssohn’s ‘Adagio’, composed when she was<br />

just 18. Fanny is said to have excelled as a composer<br />

of short musical forms. This is not surprising<br />

given that, unlike her brother, the composer Felix<br />

Mendelssohn who travelled throughout Europe<br />

8 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

From left to right:<br />

Top row: Fanny Mendelssohn, 1842,<br />

by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim and<br />

Lithograph of Clara Schumann, 1839,<br />

by Andreas Staub<br />

Middle row: Ethel Smyth and her dog,<br />

Marco, 1891 and Henri Manuel’s Portrait<br />

of Lili Boulanger, originally published in<br />

Comœdia illustré, 1913<br />

Bottom row: Florence Price and<br />

Gabriela Montero<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 9

Above: Processing<br />

suffragettes, c. 1908, World’s<br />

Graphic Press Limited, 36-38<br />

Whitefriars Street, Fleet Street,<br />

London. ‘Women’s Social and<br />

Political Union’ teams draw the<br />

carriage of released prisoners<br />

away from Holloway, LSE<br />

Library. Source: Wikimedia<br />

Commons<br />

with his orchestral compositions, Fanny was<br />

expected to stay home playing salon concerts.<br />

“Fanny was allowed to play the piano, as long<br />

as it supported her brother and made her more<br />

attractive as a marriage prospect. Teaching the<br />

piano was also an acceptable occupation for<br />

women, at a time when most professions were<br />

closed to women,” notes Ruth. Fanny’s ‘Adagio’<br />

“is tricky to get right. It’s a delicate balance of a<br />

slightly naïve, sweet and pleasant [melody] with a<br />

[calming] meditation, and to try and find exactly<br />

the right tempo to let it be a dream, and to open<br />

with it, is difficult.”<br />

Fanny Mendelssohn’s near contemporary, Clara<br />

Schumann, had much greater freedom to travel,<br />

performing in concerts throughout Europe as<br />

a highly celebrated pianist. From childhood to<br />

middle age, she produced a good body of work but,<br />

following the early death in 1856 of her husband,<br />

the composer Robert Schumann, Clara largely gave<br />

up composing, leaving a legacy of just 23 published<br />

works. In preparing to perform Clara Schumann’s<br />

‘Three Romances’ Ruth found that “it took a lot of<br />

personal energy to discover the depth in it. But I<br />

had played the same piece for another recital in<br />

France in May, and I worked quite a lot on it then,”<br />

adding, “it has been a year where I’ve begun to play<br />

more women’s repertoire.”<br />

Although she is now recognised as an important<br />

composer of the Romantic era, Schumann herself<br />

seemed to have absorbed the prevailing view that<br />

women did not have the ‘genius’ to create great<br />

music. “I once believed that I possessed creative<br />

talent,” she claimed, “but I have given up this idea;<br />

a woman must not desire to compose – there has<br />

never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect<br />

to be the one?” No doubt Clara would have been<br />

able to put more energy into her composing if<br />

she did not have eight children to provide for<br />

and a husband whose health was precarious. As<br />

Ruth comments, “When it comes to women, the<br />

perception of competence is always the issue.<br />

Not just in music, but everywhere. And it’s not<br />

just men, women can be just as sexist without<br />

realising it.”<br />

The work of English composer Ethel Smyth<br />

(see feature on p.14) was new to Ruth. “Her ‘Violin<br />

Sonata’ required the most preparation because<br />

10 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Left: Winnaretta Singer’s selfportrait,<br />

c.1885, Foundation<br />

Singer-Polignac, Paris.<br />

Source: Wikimedia Commons<br />

it is thirty minutes long. It also has a significant<br />

emotional content because there is a discussion<br />

in it – it is more like an essay than a short soliloquy.<br />

And there’s a lot to get together with the piano<br />

as well, the score is complicated.” Ruth continues,<br />

“As a musician, what I am always looking for is<br />

a musical challenge, regardless of who wrote it.<br />

I was really glad to get to know Smyth’s sonata,<br />

because it is an interesting piece of music that I<br />

can include in any programme or any situation.”<br />

Lili Boulanger’s ‘D’un matin de printemps’ was a<br />

piece that Ruth learned during the pandemic but<br />

had not performed. “It is the one that surprised<br />

me. The difficulty arises from the fact that it is so<br />

short – it’s there and then suddenly … it’s gone!”<br />

Sadly, this could also describe its composer’s life.<br />

A child prodigy, Lili Boulanger was the first female<br />

winner of the Prix de Rome composition prize<br />

in 1913. Between 1911 and 1918 she composed<br />

some two dozen works but, having suffered with<br />

chronic ill health throughout her life, she died at<br />

just 24 years of age.<br />

For Florence Price’s ‘Fantasie in G minor’<br />

(see feature on p.20), Ruth referred to ‘Roots’,<br />

a recording of Black US classical music by the<br />

young American violinist Randall Goosby.. “He<br />

plays it beautifully,” she says. “When I came to<br />

play it, I couldn’t make sense of it at first. But<br />

when you put it together with the poetry of<br />

Georgia Douglas Johnson, it suddenly comes<br />

alive. When you contextualise it, it sort of pops.”<br />

French composer Maurice Ravel snuck on<br />

to the programme in part because his career<br />

owes a huge debt to Winnaretta Singer, the<br />

sewing machine heiress, who was one of the<br />

most passionate supporters of his work. From<br />

1905 until 1931, Ravel performed and sometimes<br />

premiered his works in her salon. For ‘Scoring<br />

Suffrage’ Ruth performed Ravel’s ‘Tzigane’, which<br />

she describes as “an amazing piece.” It was both<br />

inspired by and dedicated to British-Hungarian<br />

violinist Jelly D’Aranyi who was one of the few<br />

celebrated women in the male-dominated world<br />

of classical violinists of the time. ‘Tzigane’ was<br />

just one of many pieces written especially for her.<br />

In 1922, and at the height of his career, Maurice<br />

Ravel met d’Aranyi in London at a private concert<br />

where she and Hans Kindler performed Ravel’s<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 11

Top: Riverside view of Florence on opening<br />

night. Photo by Marco Berni<br />

Above Jelly d’Aranyi in 1923.<br />

Source: Wikimedia Commons<br />

Right: Ruth Palmer testing acoustics at the<br />

1901 Arts Club in London,<br />

-Calliope Arts Archive<br />

‘Duo sonate’. Ravel persuaded d’Aranyi to stay<br />

on and play what were then popular Romani<br />

melodies for him, which she did well into the<br />

early hours of the morning. He was so taken with<br />

her performance that he promised to compose a<br />

concert piece for her and wrote “you have inspired<br />

me to write a short piece of diabolical difficulty,<br />

conjuring up the Hungary of my dreams. Since it<br />

will be for violin, why don’t I call it Tzigane?” The<br />

piece is indeed a challenge for the violinist and<br />

demands to be played by throwing caution to the<br />

wind. Ruth was certainly up to the task, showing<br />

off the range of her instrument as well as her<br />

own virtuosity.<br />

Winnaretta Singer enjoyed introducing her<br />

friends to each other and starting cultural<br />

collaborations across the arts. For Ruth, “the<br />

opportunity to collaborate with Claudia was<br />

probably the biggest draw on this project.<br />

Claudia is so knowledgeable, and she has an<br />

artistic character that allows her to connect the<br />

dots in a way that is instinctual. When I suggested<br />

pieces from the repertoire, she was able to find<br />

the connections among the various writers and<br />

poets and activists at the time. There was an<br />

12 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

organic process to the way we found the links<br />

together. I learned that I could discover things as<br />

well. So that was fun.” The enjoyment that Claudia<br />

and Ruth experienced working in partnership on<br />

‘Scoring Suffrage’ recalls the final words of ‘The<br />

March of Women’, the suffrage anthem written by<br />

Cicely Hamilton and composed by Ethel Smyth:<br />

March, march, many as one<br />

Shoulder to Shoulder and friend to friend.<br />

MARGIE MACKINNON<br />

‘Scoring Suffrage’ was performed as part of the<br />

‘Palace Women’ programme organised by The<br />

British Institute of Florence, Il Palmerino Cultural<br />

Association and Calliope Arts This project is made<br />

possible thanks to the support of Enjoy, Respect<br />

and Feel Florence, funded by Italy’s Ministry<br />

of Tourism, the Fund for Development and<br />

Cohesion, the Municipality of Florence and Feel<br />

Florence. Special thanks to donors Alice Vogler,<br />

Donna Malin, Margie MacKinnon and<br />

Wayne McArdle.<br />

Described as ‘the most distinctive violinist<br />

of her generation’ (The Independent),<br />

violinist Ruth Palmer is praised for her<br />

‘intensity’ and ‘poetic grandeur’ (The<br />

Guardian).<br />

Her Direct-to-Disc LP of Bach is available<br />

on Berliner Meister Schallplatten. Earlier<br />

recordings’ critical acclaim includes<br />

‘impeccable astringent Bartók and warm,<br />

profound Bach’ (The Observer), while her<br />

Shostakovich recording won a Classical<br />

BRIT.<br />

She’s performed with James Ehnes,<br />

Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, Yutaka<br />

Sado, Carlo Rizzi, BBC Philharmonic,<br />

and at the British Embassy’s British<br />

Week in Havana, and for King Charles<br />

III (then Prince of Wales) and Queen<br />

Elizabeth II. She’s appeared on radio and<br />

television internationally. When Ruth<br />

collaborated with Rambert and Sydney<br />

Dance Companies, ‘it was sometimes<br />

a struggle to concentrate on the dance<br />

when the violinist was so compelling’<br />

(Sunday Telegraph).<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 13

Above: Scholar Claudia Tobin performs ‘Scoring Suffrage’ in Florence.<br />

Photo by Marco Berni<br />

Right: Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s portrait of his sister Christina, 1866,<br />

private collection. Source: Wikiart<br />

14 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

The Words We’d<br />

Like to Meet<br />

Scholar Claudia Tobin on ‘Scoring Suffrage’<br />

CChristina Rossetti, Constance Smedley, Ethel Smyth, Vernon Lee,<br />

Cicely Hamilton, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Emmeline Pankhurst,<br />

Marina Tsvetaeva and Anna Akmatova are just some of the<br />

women writers and social reformers forming part of Florence’s<br />

“Scoring Suffrage” performance. This brief conversation with<br />

British scholar Claudia Tobin will send you to the book shelf,<br />

to re-read ‘old friends’ or to reach for new voices you’ve never<br />

heard before. Amidst plays, poems, novellas, essays and letters,<br />

Claudia’s interview is an invitation to seek out the words of<br />

nineteenth- and early twentieth-century women. Their hopes,<br />

whether shattered or still shining bright, are awaiting discovery<br />

– in their own words.<br />

Were all the women featured social activists?<br />

The starting point for the Florence performance was the suffrage<br />

moment, but I think it’s important to note that these women are<br />

united by an extraordinary commitment to their art and the<br />

causes they supported, but they didn’t share the same political<br />

persuasions, and that message – even by itself – is relevant to<br />

today’s world. They were all ‘fighting spirits’ and they fought for<br />

suffrage or the right to express themselves, but they do not belong<br />

to one side of the political spectrum or a single political party,<br />

which became clear as our research unfolded. Christina Rossetti<br />

(1830-1894), for instance, was devoted to poetry – to the point<br />

that she didn’t marry to pursue it. She was religiously devout and<br />

supported humanitarian causes, striving to follow the Florence<br />

Nightingale model, and her poems are full of redemptive female<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 15

Left: Cover of Vernon Lee’s<br />

The Ballet of The Nations.<br />

1915 edition, from the library of<br />

Il Palmerino Cultural Association.<br />

Above: Constance Smedley,<br />

undated.<br />

Source: Wikimedia Commons<br />

Right: The Ballet of The Nations<br />

performed at Il Palmerino Cultural<br />

Association, 2019.<br />

Source: Il Palmerino Archive<br />

figures, but she was not in favour of votes for<br />

women, although she does concede that “mothers<br />

would make good members of Parliament”.<br />

Tell us about a highlight from ‘Scoring<br />

Suffrage’ that combines spoken word and<br />

music.<br />

In the performance, we explore the figure of<br />

the wanderer, the gypsy. So, we looked at the<br />

archetypal artist, the wandering minstrel – a<br />

figure of freedom and free movement - in a<br />

few different works of poetry and music. As a<br />

complement to Maurice Ravel’s ‘Tzigane’, I read<br />

Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva’s ‘Our Sweet<br />

Companions – Sharing Your Bunk and Your<br />

Bed’. She was an exile, and suffered greatly in<br />

early twentieth-century Russia, and was deeply<br />

influenced by Pushkin’s narrative poem ‘The<br />

Gypsy’.<br />

Another piece I’d like to include in the future,<br />

on this same theme, is The Minstrel, which<br />

Constance Smedley collaborated on, in 1915,<br />

with her husband Maxwell Armfield. It features<br />

a wandering musician, in a country destroyed<br />

by war. Both Smedley and Armfield were<br />

committed pacifists, and in that same period,<br />

they set up experimental theatre companies<br />

in London, providing body-movement scripts.<br />

They had a vision of really strict choreography<br />

in their productions, for which Smedley<br />

provides drawings, envisioning them as a<br />

rhythmic structure.<br />

16 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

From your description, Smedley’s experience<br />

sounds akin to that of Vernon Lee, also a pacifist,<br />

interested in aesthetics and the psychological<br />

implications of physical expression.<br />

Yes, their interests are very much related. Smedley<br />

and Lee shared the pacifist outlook – in the<br />

First World War. [Armfield wrote the introduction<br />

to Lee’s satirical play, The Ballet of the Nations,<br />

published in 1915, before The Minstrel.] Lee,<br />

Smedley’s circle, Virginia Woolf’s circle were well<br />

travelled. They had friends in Belgium, Germany,<br />

France and England. The nations were at war but<br />

they wanted their friendships to remain. In reality,<br />

Lee’s loss of popularity as an author is often said<br />

to be linked to the letters she wrote to friends<br />

advocating peace.<br />

‘Scoring Suffrage’ includes snippets of<br />

letters and essays by women, in addition<br />

to their poetry. How did these women’s<br />

correspondence contribute to their quest for<br />

freedom of expression?<br />

Ethyl Smyth and Vernon Lee became friends and<br />

ended up dedicating work to each other. Lee<br />

dedicated the play Ariadne in Mantua to Smyth,<br />

thanking her for her work and begging her for<br />

music. They were what Smyth called ‘female<br />

labourers in the field of art’ and they moved in<br />

the same circles.<br />

Their correspondence crossed to America<br />

too, to involve another figure Charlotte Perkins<br />

Gilman – a friend of Smyth’s. She was an American<br />

suffragette and writer who wrote political verse<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 17

18 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

and songs for suffrage. Perkins Gilman cofounded<br />

The Women’s Peace Party, in 1915. Her<br />

novella The Yellow Wallpaper is haunting and<br />

vividly told. It speaks of a woman on the brink<br />

of madness, prescribed bed rest by her husband.<br />

She is not allowed to work and is held prisoner in<br />

her room, watching the peeling yellow wallpaper.<br />

In the programme, we cite a letter she wrote to<br />

Vernon Lee, thanking her for helping to spread<br />

the ideas she felt were important… not that they<br />

always agreed. They didn’t, because these women<br />

were complex figures.<br />

As an author and exhibition curator, you’ve<br />

often worked with the mixing of various<br />

media. How did this play out in the time<br />

period studied as part of the ‘Scoring<br />

Suffrage’ grant?<br />

There are instances in which music inspires<br />

words, and other cases in which words give way<br />

to silence, that then becomes sound or music.<br />

Virginia Woolf’s relationship with music is one<br />

interesting case study. In the late Nineteenth<br />

Century, many artists were interested in the<br />

intermingling of the senses, and started exploring<br />

fields like Synaesthesia. Kandinsky claimed to<br />

‘hear colours’, and French artist Sonia Delaney<br />

discusses the issue at length as well. The idea<br />

of [the brain processing information through<br />

unrelated senses] leads to the discussion of<br />

where one art form ends and the other begins. In<br />

this very fruitful period – in the late nineteenth<br />

and early twentieth century – there was the<br />

idea that music had the power to offer a sense<br />

of companionship. It was an invisible presence,<br />

a powerful voice… which reminds me of Russian<br />

poet Anna Akhmatova, who personified music as<br />

female, in her poem titled ‘Music’. I’m interested<br />

in where the different art forms begin and end<br />

and where they fuel and inspire other media,<br />

and it’s clear that music and poetry are natural<br />

companions and have been for a long time.<br />

Left, clockwise from top left: Vernon Lee by John Singer Sargent, 1881; Anna Akhmatova by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin,<br />

1922; Ethyl Smyth by John Singer Sargent, 1901; Charlotte Perkins Gilman by Frances Benjamin Johnston, c. 1900.<br />

Source: Wikimedia Commons<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 19

Notable Women<br />

AComposers Florence Price and Ethel Smyth<br />

A supermoon illuminated the sky over the Arno as<br />

the music of women composers filled Florence’s<br />

Lyceum Club for the inauguration of ‘Palace<br />

Women – Oltrarno and Beyond’. Serendipity?<br />

Perhaps, but there is no doubt that the presence<br />

of this symbol of female energy added to the<br />

sense that ‘Scoring Suffrage’ (as the recital was<br />

called) was an exceptional event. Below, we take a<br />

closer look at two of the composers whose work<br />

featured in the recital.<br />

Near contemporaries from opposite sides<br />

of the Atlantic, Florence Price (1887-1953) and<br />

Ethel Smyth (1858-1944), fought against prejudice<br />

to have their compositions recognised and<br />

performed. The body of work they left behind is<br />

testament to their talent and perseverance.<br />

Portrait of Florence Price<br />

Looking at the Camera,<br />

undated, Papers Addendum<br />

(MC 988a). Special Collections,<br />

University of Arkansas<br />

Libraries, Fayetteville<br />

FLORENCE PRICE<br />

Florence Beatrice Smith was born into a<br />

prominent family in the Black community of<br />

Little Rock, Arkansas. Her mother was a talented<br />

singer and pianist who quickly recognised her<br />

daughter’s musical gifts and sent Florence to<br />

Boston to study at the New England Conservatory.<br />

In addition to excelling at her piano and organ<br />

studies, she took private lessons in composition<br />

with the school’s director. That Florence<br />

encountered discrimination along the way is<br />

evidenced by the fact that, in her final year at the<br />

Conservatory, she falsely registered as a Mexican<br />

resident in an effort to avoid harassment from<br />

segregationist Southern white students, not an<br />

unusual occurrence for students of colour. In<br />

fact, Florence’s background included a mixture<br />

of French, Indian, Spanish and African American<br />

ancestry, and she would draw from this “racial<br />

melting pot” in composing her music.<br />

Florence returned to Little Rock after<br />

graduation and married Thomas Price, an upand-coming<br />

lawyer. When racial tensions in the<br />

city later erupted in violence, the couple, with<br />

their two young daughters, joined the Great<br />

Migration of Blacks fleeing northward, eventually<br />

settling in Chicago. Florence continued to study<br />

composition, publishing four pieces for piano<br />

in 1928. When her marriage ended in divorce in<br />

1931, she supported her family by working as an<br />

organist for silent film screenings and composing<br />

jingles for radio advertisements.<br />

Her ‘break’ came when she won the 1932<br />

Rodman Wanamaker Award, a competition for<br />

Black composers, with her entry ‘Symphony<br />

No 1 in E minor,’ which was performed by the<br />

Chicago Symphony Orchestra as part of the<br />

World’s Fair in 1933. The Chicago Daily News’<br />

music critic described it as “a faultless work<br />

… that speaks its own message with restraint<br />

and yet with passion … worthy of a place in the<br />

regular symphonic repertoire.”<br />

20 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

In explaining how Price went from relative<br />

obscurity to being showcased by a major<br />

orchestra, pianist and music historian Dr<br />

Samantha Ege notes that, “there’s this idea that<br />

this all-white, all-male orchestra just sort of<br />

magically took an interest in Price’s music, but<br />

actually it was Maude Roberts George working<br />

behind the scenes, supporting Price in getting the<br />

score finished and making sure the world could<br />

hear it.” Ege explains that both Price and George<br />

were part of an active network of Black women,<br />

many with conservatory training, who supported<br />

a growing musical community during the 1920s<br />

and 1930s. George’s support for Price extended to<br />

personally underwriting the cost of the Chicago<br />

Symphony performance.<br />

Even as she tirelessly composed new pieces,<br />

Price continued formal studies in harmony,<br />

orchestration and composition at the Chicago<br />

Musical College and the University of Chicago.<br />

Her music was performed by at least nine<br />

major orchestras, and her vocal and instrumental<br />

chamber music and piano compositions were<br />

sung by some of the great soloists of her day<br />

– including Marian Anderson who famously<br />

performed Price’s arrangement of a spiritual on<br />

the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, when<br />

she was barred on racial grounds from appearing<br />

in Washington’s Constitution Hall. Price also<br />

taught piano and mentored young composers.<br />

While she succeeded in publishing some of her<br />

scores, most were still in manuscript form at the<br />

time of her death.<br />

Price’s compositions clearly reflect the influence<br />

of her classical training. For those familiar with<br />

this repertoire, echoes of Brahms, Liszt and<br />

Chopin are evident in her work. Musicologists<br />

cite Dvorak’s ‘New World Symphony’ as the<br />

primary model for her first symphony. But what<br />

sets her compositions apart is the way in which<br />

she integrated musical idioms from outside the<br />

traditional orchestral world. In particular, she<br />

drew on the African American soundscape of<br />

church spirituals, plantation and folk songs with<br />

which she would have been familiar from her<br />

Southern childhood. Written descriptions cannot<br />

hope to capture the emotion of this music and<br />

encountering it for the first time is a pleasure that<br />

awaits the uninitiated. Ege, who has recorded<br />

many of Price’s pieces, says, “I wanted to recreate<br />

for the listener that sense of wonder I had when<br />

I first heard the music … It was a real invitation<br />

to listen … to enter this world with her … and I<br />

think it’s the way she treats African folk songs<br />

with such respect and sensitivity …” Ege adds that<br />

Price would have been aware that touring groups<br />

in the late Nineteenth Century had made the<br />

Negro spiritual an art form. Music that had once<br />

been denigrated because of its origins was seen<br />

in a new light in the concert hall.<br />

In 1943, Price wrote a letter to Serge Koussevitzky,<br />

the conductor of the highly regarded Boston<br />

Symphony Orchestra, hoping to encourage him<br />

to read some of her scores. Explaining her style,<br />

she told him, “I believe I can truthfully say that I<br />

understand the real Negro music. In some of my<br />

work I make use of this idiom undiluted. Again,<br />

at other times it merely flavors my themes. I<br />

have an unwavering and compelling faith that a<br />

national music very beautiful and very American<br />

can come from the melting pot just as the nation<br />

itself has done.” Unfortunately, Koussevitzky was<br />

not interested in programming any of her work.<br />

Price’s ‘Fantasie No. 1 in G minor’, which was<br />

performed as part of ‘Scoring Suffrage’, is a<br />

wonderful example of her ability to seamlessly<br />

insert recognisable African American themes<br />

into the highly structured form of classical<br />

European concert music. It is one of four<br />

‘Fantasies’, which at one time had been<br />

presumed lost. Fortunately for music lovers, in<br />

2009, a cache of dozens of boxes containing<br />

the composer’s letters and manuscripts was<br />

discovered in a long-neglected house in Illinois<br />

that had been Price’s summer refuge. That<br />

discovery heralded a renaissance in Price’s work<br />

and a renewed interest in performances and<br />

recordings of her extensive catalogue. Her “very<br />

beautiful and very American” music deserves to<br />

be heard by a much wider audience.<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 21

English composer and<br />

suffragette Ethel Smyth<br />

(1858-1944). Image from<br />

the United States Library<br />

of Congress’s Prints and<br />

Photographs division<br />

ETHEL SMYTH<br />

Her Majesty’s Prison Holloway is perhaps London’s<br />

most famous institution for women. In March 1912,<br />

it was the venue for an exceptional performance<br />

of the Suffragette anthem ‘The March of Women’.<br />

The chorus was sung by inmates marching in the<br />

quadrangle, while the anthem’s composer, Ethel<br />

Smyth, leaned out of her prison cell window to<br />

conduct them with her toothbrush. Smyth had<br />

been arrested two months earlier, along with her<br />

friend Emmeline Pankhurst, for throwing stones<br />

at the houses of politicians who opposed votes<br />

for women. Smyth herself took credit for teaching<br />

Pankhurst how to throw stones and practiced with<br />

her by aiming stones at trees near the home of a<br />

fellow activist. At the age of 52, Smyth had joined<br />

the Women’s Social and Political Union, founded<br />

by Pankhurst in 1903, to campaign for women’s<br />

suffrage. She took two years out from her musical<br />

career, by then well-established, to devote herself<br />

to the cause. This was typical of the passion and<br />

fearlessness with which Smyth approached every<br />

aspect of her life.<br />

Her determination not to be bound by social<br />

convention was apparent early on. Born in 1858<br />

into a well-to-do family in Victorian England – a<br />

time when it was unseemly for women of her class<br />

to have their own profession – Smyth overcame<br />

her father’s objections to her unshakeable desire<br />

to study music by locking herself in her room and<br />

refusing to eat or leave it until he relented. She<br />

was admitted to the Leipzig Conservatory in 1887<br />

and met some of the most renowned composers<br />

of the day, including Johannes Brahms, Clara<br />

Schumann, Antonin Dvorak and Pyotr Tchaikovsky.<br />

The latter would eventually recognise Smyth as<br />

“one of the few women composers whom one<br />

can seriously consider to be achieving something<br />

valuable in the field of musical creation.”<br />

Tchaikovsky’s backhanded compliment typifies<br />

the prejudice faced by female composers. Her<br />

work was not evaluated on its own merits but as<br />

that of a “woman composer”. While some critics<br />

praised the “masculinity” of her more powerful<br />

compositions, others complained that her work<br />

was lacking in the feminine charm to be expected<br />

of woman, whatever her other accomplishments.<br />

Following her formal education, Smyth<br />

travelled throughout Europe, mainly in Germany<br />

and Italy, refining her style, falling in and out of<br />

love and cultivating friendships with patrons,<br />

musicians and other intellectuals who were part<br />

of the artistic milieu of the time. She returned<br />

to London in 1889 where she composed works<br />

ranging from choral arrangements and chamber<br />

music to orchestral pieces and operas. Her<br />

first of six operas, ‘Fantasio’, debuted in 1898 in<br />

Weimar, Germany. Despite the insidious prejudice<br />

against women as composers, Smyth was able<br />

to get many of her works performed, thanks to a<br />

combination of talent, support from conductors<br />

such as Sir Thomas Beecham, and her own<br />

formidable ambition.<br />

Smyth’s ‘Sonata for Violin and Piano in A<br />

minor’, composed in 1887 and dedicated to her<br />

friend, Lili Wach, the daughter of composer Felix<br />

22 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Mendelssohn, was the centrepiece of ‘Scoring<br />

Suffrage’. A review of its first performance in 1887<br />

praised the musicians while declaring that the<br />

work itself lacked originality and was a slavish<br />

copy of Brahms, a critique that Smyth dismissed<br />

in her memoir Impressions that Remained saying,<br />

“A listen to the piece will prove just how wrong<br />

the reviewers were!” When violinist Ruth Palmer<br />

(see feature on p. 6) first looked at Smyth’s violin<br />

sonata, she thought, “There’s so much Brahms<br />

here. Where’s the Smyth? But when you get to<br />

know it, you realise, actually, she’s got so much<br />

personal power and narrative in that piece.<br />

She is not Brahms at all. It’s just that that is the<br />

vernacular that she was speaking in because<br />

that’s what was going on in Europe at the time.<br />

But she brings her own voice to the music and<br />

she says something original with it.”<br />

In 1912, Smyth began to lose her hearing,<br />

eventually giving up composing as a result. She<br />

turned from music to writing, completing ten<br />

mostly autobiographical volumes. In them, she<br />

writes openly about her love affairs, many with<br />

famous women, including Emmeline Pankhurst,<br />

writers Virginia Woolf and Edith Somerville, and<br />

the heiress Winnaretta Singer. Her only male<br />

lover is said to have been Henry Brewster, the<br />

librettist of some of her operas, with whom she<br />

had a lifelong friendship. It is disappointing (if<br />

not surprising) to discover that, according to<br />

biographer Dr Leah Broad, Smyth held bigoted<br />

opinions about race, subscribing to the belief in<br />

white English superiority, despite having faced<br />

prejudice throughout her life because of her<br />

gender and sexuality. In this, she went along with<br />

views that were prevalent at the time.<br />

Yet there is no denying Smyth’s many<br />

accomplishments. She was the first woman to<br />

have an opera (‘The Forest’) staged at the New<br />

York Metropolitan Opera, in 1903. In 1922, She<br />

was named Dame Commander of the Order of<br />

the British Empire, the first female composer<br />

(and possibly the only one with a criminal<br />

record!) to be given the title of Dame. She was<br />

the first woman to receive an honorary degree<br />

in music from Oxford University, in 1926. More<br />

recently, Smyth was the first woman composer to<br />

have an opera staged at Glyndebourne, in 2022.<br />

Their production of Smyth’s 1906 magnum opus,<br />

‘The Wreckers’, attracted rapturous reviews (and<br />

favourable comparisons to Benjamin Britten’s<br />

‘Peter Grimes’) for the staging and for the work<br />

itself, with the Financial Times critic claiming,<br />

“there is no English opera written before or after<br />

‘The Wreckers’ that can match Smyth’s openhearted,<br />

unapologetic, no-holds-barred passion.”<br />

Smyth’s final major work, a choral symphony<br />

called ‘The Prison’ was first performed in 1930 but<br />

only recorded 90 years later. That recording, by<br />

Chandos, won a Grammy in 2021.<br />

Among her many accolades, I like to think<br />

that Dame Ethel would have been particularly<br />

‘chuffed’ to have been given a seat at Judy<br />

Chicago’s Dinner Party (1974-79). In this groundbreaking<br />

installation artwork, a triangular table<br />

with place settings for 39 significant women<br />

from history and myth, Smyth finds herself in the<br />

company of Sojourner Truth, Georgia O’Keefe,<br />

Artemisia Gentileschi and her dear friend,<br />

Virginia Woolf, among others. Representing her<br />

work as both a composer and a champion of<br />

women’s rights, Smyth’s place setting includes<br />

musical motifs such as a plate in the form of<br />

a grand piano, a treble clef incorporating her<br />

initials and a metronome. On the runner, a tweed<br />

suit has been laid out, as if being tailored. This<br />

is a reference to Smyth’s preference for dressing<br />

in a ‘masculine’ style, and, perhaps, to her wish<br />

to be considered as worthy a composer as any<br />

of her male counterparts.<br />

Passionate composer, radical activist, prolific<br />

writer and non-conforming lover of women (and<br />

at least one man), Dame Ethel Smyth would be<br />

a fascinating guest at any fantasy dinner party.<br />

MARGIE MACKINNON<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 23

24 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

“You oughta be<br />

in pictures”<br />

Banca d’Italia showcases 75 years of women in art<br />

Towards Modernity [Verso la Modernità] is a survey show that encompasses<br />

75 years of shifting culture. All but six of its works are painted by male<br />

artists who echo the winds of social change affecting female representation<br />

in art. From the iconic mother figure, to the ‘new nude’ and the burgeoning<br />

‘modern woman’, this show at Florence’s Banca d’Italia, on via dell’Oriolo,<br />

is open for free guided tours through on-line appointment, until 10 March<br />

2024. Curated by Ilaria Sgarbozza and Anna Villari, the exhibition<br />

displays paintings and sculpture that reflected and shaped the female<br />

experience in Italy from 1871 to the mid-1900s...<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 25

Angel of the Hearth?<br />

The stairwell of the Banca d’Italia building is<br />

impressive to say the least – an imposing<br />

upward-moving swirl of marble that rises<br />

slowly, like the triumphant notes of an Italian<br />

march for unification. The Black Angel at the<br />

foot of the stairs stands out as a small but<br />

striking contrast to this otherwise stone-white<br />

world. “We chose to begin the Towards<br />

Modernity exhibition with this wonderful<br />

example of the Ritorno all’ordine movement,”<br />

says exhibition co-curator Anna Villari. “By the<br />

1920s, artists in Italy were already responding to<br />

what they considered the destruction of<br />

figurative art by the avant-garde currents,<br />

and were calling for a return to the human<br />

figure, which was cleaner and sharper than in<br />

previous decades, as with The Black Angel.”<br />

In 1922, Polish sculptor Maryla Lednicka-<br />

Szczytt – who eventually made her living<br />

carving decorative figureheads for the bow of<br />

cruise ships – debuted in Paris during the city’s<br />

heyday, and while there, she worked<br />

with designer Adrienne Gorska, whose more<br />

famous sister is Tamara de Lempicka.<br />

Following Lednicka-Szczytt’s move to Italy and<br />

her solo exhibition in Milan, in 1926, she was<br />

highly acclaimed by critics and collectors. The<br />

Black Angel was purchased by entrepreneur<br />

Riccardo Gualino, whose enviable collection was<br />

later acquired by the Banca d’Italia.<br />

Lednicka-Szczytt’s sculpture is thought to be<br />

a nod to the ballet Les Sylphides, which was<br />

performed in 1909 by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes,<br />

featuring Chopin’s music. While in Italy, the<br />

artist frequented the ‘Novecento Group’, brought<br />

together by art critic Margherita Sarfatti, one of<br />

Mussolini’s lovers. A supporter of the Fascist<br />

Regime, Sarfatti was a friend to artists seeking<br />

what she called “modern classicism”. [Incidentally,<br />

Sarfatti – as a woman of Jewish ancestry – was<br />

later a victim of Mussolini’s 1939 Racial Laws and<br />

forced to flee to the United States. Her passage<br />

out of Italy was not blocked by government<br />

officials]. Despite Maryla Lednicka-Szczytt’s<br />

popularity between the two world wars, the<br />

sculptor met a regrettable end. After fruitlessly<br />

pursuing her art in New York in the early 1940s,<br />

she sank into poverty and oblivion. Unable to<br />

26 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Opposite page: Maryla Lednicka-Szczytt, 1922.<br />

The Black Angel,<br />

Banca d’Italia Collection, Florence<br />

Above, left: Monumental staircase at Banca<br />

d’Italia on via dell’Oriolo<br />

Above, right and Left: Stairwell with The Black<br />

Angel.<br />

Photos courtesy of Florence’s Banca d’Italia<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 27

Below, left: Silvestro Lega’s<br />

Maternity (1881-82)<br />

Below, right: Luciano Ricchetti’s<br />

Two Little Mothers (c. 1940)<br />

maintain her previous success, Lednicka-Szczytt<br />

committed suicide in 1947. Lednicka-Szczytt’s<br />

authorship of The Black Angel – which for<br />

decades was as overlooked as the artist herself<br />

– was rediscovered in 2013 by scholar Gioia Mori,<br />

after being incorrectly attributed to De Lempicka<br />

in the 1990s.<br />

Mothers and matrons<br />

The show’s more traditional section ‘Domestic<br />

Dimensions’ starts with a lovely 1881 work called<br />

Maternity. Salvatore Lega portrays his sister-inlaw<br />

and nephew, drawing on one of Western Art’s<br />

most iconic themes: mother and child. Although<br />

the lady pictured has all the traditional sweetness<br />

of a Madonna, the discreet movement of her<br />

hand, as she re-fastens her collar post breastfeeding,<br />

brings the work into the modern realm<br />

of discrete realism.<br />

Le due mammine, authored by Luciano<br />

Ricchetti in 1940, is interesting from a historical<br />

perspective. Its protagonist looks like an ancient<br />

Roman matrona in modern garb, holding a wellfed<br />

infant on her lap. This matron and child<br />

share the scene with a much younger little<br />

mamma – as the painting’s title suggests – who<br />

is sitting in the lower left corner, caring for her<br />

baby doll. Ricchetti’s painting is best read in<br />

the context of the Battle for Births [1925-1938],<br />

a propaganda-based operation and economic<br />

incentives campaign spearheaded by Mussolini,<br />

which strove to increase Italy’s population<br />

from 40 million, in 1927 to 60 million by 1950.<br />

A nation, to be strong, needed many men; and<br />

women could participate in Italy’s new-fangled<br />

imperial expansionism by bringing many souls<br />

into the world.<br />

28 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Not far away, is another matronly figure, this<br />

time with no child in tow. Ardengo Soffici’s Water<br />

Girl, an imposing and very successful painting,<br />

fits well into the Ritorno all’ordine movement. “In<br />

this period, there was also a return to depicting<br />

Italic or Etruscan women. Artists focused on Italy’s<br />

peasant culture and its attachment to the land,”<br />

Vallari explains. “Even the ceramic wares and the<br />

jug in this painting highlight Italian traditions,<br />

albeit in a modern way.”<br />

In this section we also find the exhibition’s<br />

‘posterchild’, A Girl Sewing. Villari admits<br />

that the decision to make this 1927 oil the show’s<br />

keynote image sparked debate. Was the picture too<br />

traditional? In the end, they went with it. Leonetta<br />

Pieraccini Cecchi’s delightful, faceless rendition<br />

can be compared to Vanessa Bell’s Portrait of<br />

Virginia Wolf. Pieraccini Cecchi was an artist and<br />

tongue-in-cheek writer whose published diaries<br />

immortalised the top intellectuals of her day –<br />

she was even married to one, Emilio Cecchi.<br />

Starting in 1902, Pierracini Cecchi studied with<br />

iconic Macchiaioli painter and Accademia di Belli<br />

Arti professor Giovanni Fattori – just as women<br />

were starting to unbar the academy’s doors.<br />

“Fattori taught freedom,” Villari says. That is<br />

precisely why the anti-academy master was<br />

relegated to teaching the Women’s Section, which<br />

was seen as a punishment – by administrators,<br />

not necessarily by Fattori himself. In A Girl<br />

Sewing, viewers can revel in the figure’s bare feet<br />

– women had conquered the domestic sphere<br />

many centuries earlier, but finally, they were<br />

allowed to feel at home there.<br />

Above: Installation shot of<br />

Towards Modernity. Banca<br />

d’Italia Collection, Florence.<br />

Photos courtesy of Florence’s<br />

Banca d’Italia<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 29

Left: Felice Casorati’s Clelia (1937) and Marisa<br />

Mori’s Study of a Nude (1928).<br />

Below: Nella Marchesini’s Sleeping Woman<br />

(c. 1920)<br />

The nudes in the room<br />

It is impossible to explore art by women in<br />

twentieth-century Italy without wandering<br />

through Felice Casorati’s somewhat eerie<br />

moonscape. His desexualised, almost robotic<br />

nude on show evidences a huge change from<br />

more traditional portrayals of female nudes in<br />

Italy. This 1937 canvas is displayed in comparison<br />

with a softer but still modern nude, created in 1928,<br />

by his former student Marisa Mori, a Florentine<br />

painter best known for her ‘art affairs’ with shortlived<br />

Futurism and its second iteration Areal<br />

Painting – in a world where flight was new and<br />

speed a path to follow. Casorati’s Scuola Libera<br />

di Pittura in Turin – set up in 1927, largely thanks<br />

to Gualino’s funding – was quite the opposite<br />

of speed, however. In the exhibition catalogue,<br />

Sgarbozza describes Casorati’s work, “His cold,<br />

suspended atmospheres in elementary and<br />

geometrical settings, along with his intellectual<br />

rigour, present a modernity that is a far cry from<br />

the changeability of the Impressionists and the<br />

dynamism of the Futurists.” In person,<br />

Anna points to what is arguably the most<br />

exciting nude in the room. It is by Nella<br />

Marchesini – Casorati’s first pupil, who was<br />

eventually asked to manage the school for a<br />

period, along with fellow-artist Lalla Romano.<br />

Displayed on a table at eye-level, Marchesini’s<br />

bold nude, from 1928, was a practice piece. “She<br />

was exercising her hand,” Villari explains,<br />

“She painted on both sides, because she was<br />

saving on materials. The nude on the front recalls<br />

Mantegna’s Dead Christ [in Milan’s Pinacoteca<br />

di Brera] and the woman on the verso is a nod<br />

30 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Above and right: Woman Sitting on the Ground<br />

(1928). Banca d’Italia Collection, Florence.<br />

Photos courtesy of Florence’s Banca d’Italia<br />

to Giorgione’s Tempest.” Interestingly, the flipside<br />

is painted upside-down and made more<br />

easily viewable thanks to a large mirror set on<br />

the table. It makes for a simple but ingenious<br />

solution, in a show where, overall, the works fit<br />

well in their space.<br />

Marchesini achieved considerable acclaim at<br />

the Venice Biennale and Rome’s Quadriennale<br />

during her time and, like many women painters<br />

of her day, she modelled for other artists. In the<br />

words of her painter friend Enrico Paulucci, “She<br />

looks like she just stepped out of a Piero della<br />

Francesca panel”. As far as her own reflections<br />

on life and painting are concerned, Marchesini<br />

writes, “Art is the polar star, one of constant<br />

devotion, defended from the burdens of everyday<br />

life, and in harmony with our lives’ affections.”<br />

LINDA FALCONE<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 31

‘Palace Women’<br />

Find Common Ground<br />

Photographers and Crafters Tribute<br />

Historic Women in Tuscany<br />

32 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

What does Eleonora Toledo, a Spanish-born<br />

WDuchess with eleven children, have in common<br />

Wwith an ex-patriot poet who called her sole son<br />

W‘Pen’, a name referencing the instrument both<br />

WBrownings loved best? What does Cosimo I’s<br />

Wfavourite daughter, Isabella – who until very<br />

Wrecently was thought to have been murdered in<br />

Wbed by her jealous husband – have in common<br />

with Elizabeth Brewster Hildebrand, who lived<br />

and painted in idyllic San Francesco di Paola,<br />

some five centuries later? What common ground<br />

is shared by seventeenth-century French Princess<br />

Cristina di Lorena – who built a paradise of sorts<br />

at Villa La Petraia – and British writer and pacifist<br />

Vernon Lee, who sought to escape an outbreak<br />

of cholera, at the turn of the last century, by<br />

settling at Il Palmerino, the country house where<br />

the ‘Palace Women’ exhibition was featured in the<br />

autumn of <strong>2023</strong>?<br />

This small-scale show, forming part of the<br />

‘Palace Women’ programme, organised by the<br />

British Institute of Florence, Calliope Arts and<br />

Il Palmerino, was imagined for this Florentine<br />

colonica once frequented by the twentiethcentury’s<br />

sharpest minds, including Oscar Wilde,<br />

Edith Wharton and Virginia Woolf. The show<br />

featured photographs and handmade objects by<br />

modern-day crafters inspired by the female icons<br />

who lived and worked in the monumental venues<br />

of Cerreto Guidi, Villa La Petraia, Villa La Quiete,<br />

San Francesco di Paola, Palazzo Pitti and Poggio<br />

Imperiale.<br />

Palace Women’s ‘common ground’ is that all of<br />

the historic women featured were ‘creators of<br />

culture’, in a world where moveable property –<br />

not necessarily property itself – formed part of<br />

women’s realm of power. Grand Duchess Vittoria<br />

della Rovere is one of the most significant<br />

examples. A Medici by birth and by marriage,<br />

she was betrothed while still in the cradle, as<br />

heir to the coveted Duchy of Urbino. However, in<br />

an easily anticipated twist of history, Ferdinando<br />

II’s marriage to the twelve-year-old girl did not<br />

enable her land to be annexed to the Tuscan<br />

Opposite page: Medici Villa La Petraia by Carmen Cardellicchio.<br />

Above: Workshop Students by Viola Parretti<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 33

Below, from left to right: Negar<br />

Azhar Azari by Olga Makarova;<br />

Kirstie Mathieson by Valentina<br />

Bellini; Brenda Luize Roepke<br />

by Carmen Cardellicchio, Ayako<br />

Nakamori by Valentina Bellini.<br />

All photos courtesy of Gruppo<br />

Fotografico Il Cupolone and<br />

Calliope Arts Archive<br />

Grand Duchy. Before the cousins tied the knot,<br />

Vittoria’s properties were swooped up by the Papal<br />

powers, because a girl heir made manoeuvring of<br />

this sort easy. But the young Vittoria did keep her<br />

‘moveable properties’, which included pictures by<br />

Titian and Rafael, now at the Pitti Palace. Perhaps<br />

posterity is lucky that her marriage ended up being<br />

unhappy, because the ‘separate life’ she led from<br />

her paedophilic husband engendered one of the<br />

earliest ‘colonies’ devoted to women’s creativity, up<br />

at Poggio Imperiale. While there, Vittoria sought out<br />

talented women in the fields of painting, literature,<br />

embroidery, music and more. In a word, she<br />

provided women painters, poets and composers<br />

with training, as well as the commissions they<br />

needed to build their own legacies.<br />

Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, raised by her<br />

grandmother Vittoria, was also a final heir – this<br />

time of the Medici clan. The value of moveable<br />

property and the need to carve out one’s place in<br />

the future were two of her grandmother’s most<br />

valuable lessons. As an adult, Anna Maria Luisa<br />

conceived and signed the famous ‘Family Pact’,<br />

which barred Medici property from ever leaving<br />

Florence, independent of the ruling families that<br />

took over the territory through the centuries.<br />

For this genius gesture, locals and travellers are<br />

eternally grateful. Florence is Florence thanks to<br />

her foresight.<br />

Considering how objects of cultural value were<br />

paramount to these women’s stories, was it not<br />

fitting to conceive grants for artisans using their<br />

palazzi as a starting point? Three grants were<br />

awarded to members of Florence’s international<br />

artisans’ community for this purpose. The ‘Intreccio<br />

Creativo’ collective combined wood, cord, fabric,<br />

grès and watercolour woodblock prints to create<br />

an installation called Tablescape, worthy of<br />

Elizabeth Browning’s guests at Casa Guidi; Negar<br />

Azhar Azari, a Florentine artist of Persian descent,<br />

created a ring and pendant inspired by the many<br />

windows of Poggio Imperiale’s façade. Brenda<br />

Luize Roepke designed jewellery fit for Cristina di<br />

Lorena, in white gold and diamonds. Our student<br />

grant project, which funded hands-on workshops<br />

at the Liceo Artistico Statale di Porta Romana e<br />

Sesto Fiorentino, took inspiration from the figure<br />

of Eleonora di Toledo, as students designed<br />

‘wallpaper’ for the Grand Duchess’s chambers, reinventing<br />

the pomegranate motif embroidered<br />

on several of Eleonora’s most memorable gowns.<br />

Another noteworthy part of the ‘Palace<br />

Women’ programme involved a grant awarded<br />

to the amateur photography association Gruppo<br />

34 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Fotografico Il Cupolone, whereby thirteen women<br />

photographers spent a month visiting key villas<br />

and palaces whose identity is closely linked to<br />

women’s history. For instance, photographers<br />

Daniela Giampa and Sabina Bernacchini were<br />

commissioned to immortalise scenes from the<br />

former convent of San Francesco di Paola, where<br />

German sculptor Adolf Von Hildebrand educated<br />

his five daughters (and one son) in an early version<br />

of what we’d now call ‘home schooling’. Of course,<br />

most non-villa homes do not have the likes of<br />

Richard and Cosima Wagner to supper, invite Clara<br />

Schumann or Henry James for tea, or befriend<br />

the likes of Helen Gladstone, the British Prime<br />

Minister’s daughter. Von Hildebrand’s daughters<br />

made the most of their unique education and<br />

were artistically inclined: Irene Georgii Hildebrand<br />

became a sculptor, whilst Eva and Lisl (Elizabeth<br />

Hildebrand Brewster) were painters.<br />

Photographer Paola Curradi captured corners<br />

of Villa La Quiete, where Anna Maria Luisa de’<br />

Medici chose to live towards the end of her life, as<br />

part of the Montalve Community, a laic sisterhood,<br />

and one of the earliest examples of non-ordained<br />

communities for educated women. Their Ricordi,<br />

or log books, date from the congregation’s<br />

founding in 1650 to the late 1980s and represent a<br />

‘quiet’ but extremely important page in women’s<br />

history. These volumes contain intimate snippets<br />

of life from Medici family visits, including stories<br />

of Anna Maria Luisa playing innocent jokes on<br />

the Montalve sisters. According to one note, she<br />

brings them chocolate – a New World delicacy,<br />

the likes of which they had likely never seen.<br />

The stories ‘brought back’ by the project’s<br />

photographers are far too numerous to explore<br />

here, but each picture they authored has its own<br />

story to tell – from Curradi’s Red-walled Pharmacy<br />

at Villa La Quiete, to Bernacchini’s Deep-blue<br />

Bedroom, where Rosa Vercellana, King Vittorio<br />

Emanuele II’s ‘middle-class’ morganatic wife, slept<br />

at La Petraia,. The project ‘Palace Women’, and the<br />

pictures it engendered, are like seeds for future<br />

conversations on the women of Tuscany and how<br />

their legacy takes root and blooms in our own<br />

lives today.<br />

LINDA FALCONE<br />

The ‘Palace Women’ project was made possible<br />

with the generous support of Alice Vogler, Donna<br />

Malin, Margie MacKinnon and Wayne McArdle,<br />

with the support of the Municipality of Florence,<br />

‘Enjoy Respect and Feel Florence’, the FCS and<br />

Italy’s Ministry of Culture.<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 35

“5,000 Negatives”<br />

Safeguarding the Wulz sisters’ legacy at FAF<br />

Above: The digitalisation process of ‘5,000 Negatives’ at Art Defender, October <strong>2023</strong><br />

36 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2023</strong>

Like many women artists of centuries<br />

past, the Wulz sisters, Wanda (1903-1984)<br />

and Marion (1905-1993), followed in their<br />

grandfather and fathers’ footsteps (photographers<br />

Giuseppe and Carlo Wulz, respectively). Both girls<br />

showed precocious talent behind the camera<br />

lens, at a time when photography was still largely<br />

considered a craft, not an art form in its own<br />

right. Often represented as twins, Wanda and<br />

Marion were Carlo’s models from the cradle<br />

onwards. When his photo-ready babies grew<br />

into intriguing young women, Wanda and Marion<br />

became two of Carlo’s Three Graces. To say the<br />

sisters were photogenic is an understatement.<br />

In their household, photography was a game, a<br />

constant switching of costumes and scenes, and<br />

they had several ‘life-changing’ opportunities to<br />

stand behind the camera rather than in front of it.<br />

Wanda is celebrated as a top exponent of<br />

futurist photography, for her experimental flair<br />

and daring overlays, like the ultra-famous Cat and<br />

I. Marion, who has become a centre of attention<br />

only recently, was interested in photo reportage,<br />

capturing historic WWII liberation scenes from<br />

the window of the Wulzs’ flat, in the manner of<br />

Elizabeth Browning and Casa Guidi Windows.<br />

Although Marion produced photography rather<br />

than poetry, her historical images were poetic,<br />

in their own way. When the sisters took over the<br />

family’s successful photography studio in Trieste<br />

in 1928, they continued the family’s portraiture<br />

business, adding to an exceptional archive that<br />

features top figures of their day, from celebrity<br />

athletes and entertainers, to nobility and top<br />

exponents of fashion and culture.<br />

October <strong>2023</strong> marked the start of a new<br />

collaborative project called ‘5,000 Negatives’,<br />

aimed at safeguarding the sisters’ legacy, through<br />

the creation of an inventory and the restoration,<br />

digitalisation and improved archive accessibility<br />

of the Wulz Photographic Studio Archive of<br />

Trieste, a treasure trove of negatives, prints and<br />

archival documentation acquired by Fondazione<br />

Alinari per la Fotografia (FAF) in 1986. This project,<br />

developed by FAF, is made possible thanks to a<br />

grant from Fondazione CR Firenze and Calliope<br />

Arts Foundation.<br />

In a recent interview, FAF Director Claudia<br />

Baroncini shares the project’s raison d’être.<br />

“Photographic archives need to be digitised, in<br />

order to preserve captured images, which are<br />

extremely fragile. We need to remember that<br />

images can actually disappear. They can vanish!<br />

Our ambition is to preserve them forever. On<br />

another level, digitalisation is important because<br />

it allows for accessibility. Let’s face it, negatives<br />

are not immediately understandable. They<br />

are not readable the way prints are. So on the<br />

one hand, digitalisation allows us to faithfully<br />

reproduce an object – in this case ‘a negative’ –<br />

using technology.<br />

But enjoyment is also a critical factor when it<br />

comes to preserving culture. Therefore, during<br />

the digitalisation process, we transform the<br />

negative into its positive image – otherwise, all<br />

you would see of the collection are ‘little black<br />

stamps’. Cultural preservation is not just about<br />

preserving an object, it involves making that<br />

object available to the public – and not just to a<br />

circle of specialists. This transferral respects and<br />

reflects the negatives’ original use. Historically,<br />

the purpose of a negative was to be printed in<br />

the positive. Analysis and sharing of the positives<br />

we acquire is phase two of this project.”<br />

Spring / Summer <strong>2023</strong> • Restoration Conversations 37

Coincidently, an all-woman team is involved<br />

in this multi-faceted endeavour and Restoration<br />

Conversations had the opportunity to talk with<br />

two of its players, in addition to Dr Baroncini. For<br />

several months, Pamela Ferrari, head of digital<br />

acquisitions at the Florence-based company<br />

Centrica, set up ‘shop’ at Art Defender, a vast,<br />

high-security art vault in Calenzano, where a<br />

plethora of Florence museums and institutions,<br />

including FAF, hold their most precious instorage<br />

works. Ferrari describes her work in<br />

lay terms, “We created a photographic set up<br />

on site, fitted with a 100-megapixel camera to<br />

acquire 5,200 Wulz negatives, through retroillumination<br />

using a lit panel.”<br />

Right. The reasoning behind the project and<br />

the basics of its execution sounded simple<br />

enough so far. We were ready to speak with<br />

photography restorer Eugenia Di Rocco, and<br />

zero in on what she and the ‘5,000 negatives’<br />