Autumn/Winter 2022

Restoration Conversations is a digital magazine spotlighting the achievements of women in history and today. We produce two issues a year: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter

Restoration Conversations is a digital magazine spotlighting the achievements of women in history and today. We produce two issues a year: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

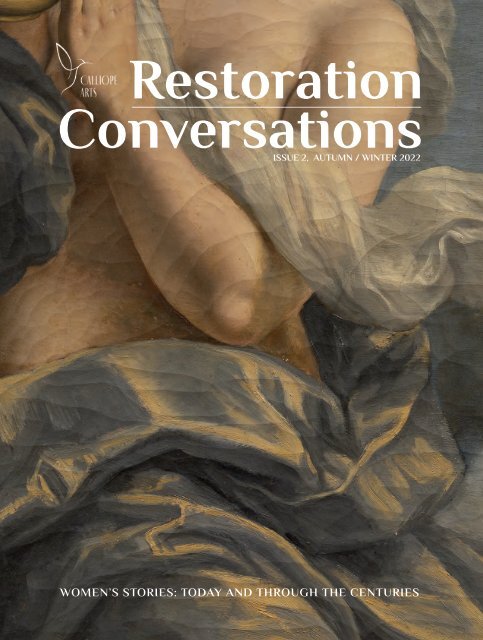

Restoration<br />

Conversations<br />

ISSUE 2, AUTUMN / WINTER <strong>2022</strong><br />

WOMEN’S STORIES: TODAY AND THROUGH THE CENTURIES<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 1

Publisher<br />

Calliope Arts Ltd<br />

London, UK<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Linda Falcone<br />

Contributing Editor<br />

Margie MacKinnon<br />

Design<br />

Fiona Richards<br />

FPE Media Ltd<br />

Video maker for RC broadcasts<br />

Francesco Cacchiani<br />

Bunker Film<br />

www.calliopearts.org<br />

@calliopearts_restoration<br />

Calliope Arts<br />

2 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

From the Editor<br />

As we conclude preparations for our <strong>Autumn</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> issue, we bid a fond<br />

farewell to ‘Fotografe!’, the Florence exhibition on women photographers,<br />

spotlighting archival treasures from the Alinari Foundation for Photography, which<br />

brought the works of extraordinary women into the public spotlight at Villa Bardini<br />

and Forte Belvedere. Wanda and Marion Wulz and Edith Arnaldi and their legacy<br />

have become part of our lives, as have the people we were fortunate to encounter<br />

through this enriching partnership whose memories fill these pages.<br />

The restoration of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Inclination, whose initial steps<br />

are documented in this issue, provides a unique opportunity for the public to ‘meet’<br />

Artemisia UpClose, as the project name suggests. It is an honor to begin to tell<br />

that story forged in paint centuries ago; its power and beauty continue to sustain<br />

us. Hats off to the project’s expert technicians whose science and manual skills<br />

will reveal the painting’s unknown secrets. We are committed to documenting each<br />

discovery as it brings new color to the canvas’s multi-century life, for our readers –<br />

and the world – to enjoy.<br />

In the issue’s third segment, we are transported to the Royal Academy of London and<br />

the Levett Collection in Florence, to name just two venues waiting to be explored,<br />

and we hope RC’s articles will succeed in whetting the appetite for ‘more’, as far as<br />

stories of women’s achievements are concerned. If that is the case, the magazine’s<br />

editorial team will have reached its own precious pinnacle of ‘achievement’, that of<br />

spreading the word on all the worthy work women do and have done, in bygone<br />

centuries and today. Thank you for being part of our growing community.<br />

Fondly,<br />

Linda Falcone<br />

Managing Editor, Restoration Conversations<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 3

CONTENTS<br />

AUTUMN/ WINTER <strong>2022</strong><br />

EXPOSURE OVERDUE<br />

6 From Shakespeare to Schiaparelli<br />

Highlights from the RC broadcast on ‘Fotografe!’<br />

14 ‘A Tendor Ardour’<br />

Julia Margaret Cameron<br />

18 Edith Arnaldi<br />

A ‘woman of the future’ from the Alinari’s Archives<br />

24 Alinari Reception<br />

A celebratory send off<br />

COME CLOSER<br />

32 Artemisia’s Descent<br />

40 Artemisia UpClose<br />

Many ways to see the mastery<br />

46 A Veiled Issue<br />

The hows and whys behind Artemisia’s veil<br />

54 There’s No Place Like Home<br />

Michelangelo’s house is Artemisia’s abode<br />

FROM SONGS TO SILK<br />

60 The ‘Archive Angel’<br />

Musica Secreta’s Laurie Stras on women’s voices<br />

68 Death of A Duchess<br />

Historical fiction or true crime?<br />

74 ‘More Bill’, Many Kennedys<br />

A spotlight on Elaine de Kooning<br />

78 ‘I Am Becoming Somebody’<br />

Paula Modersohn-Becker at the Royal Academy<br />

88 Sharing Silk<br />

An interview with Elena Baistrocchi<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 5

Above: Jazz band, Wanda Wulz, 1931, Alinari Archives, Florence.<br />

6 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

From S hakespeare<br />

to Schiaparelli<br />

Highlights from the RC broadcast on ‘Fotografe!’<br />

During our autumn episode of Restoration<br />

Conversations, live-streamed on location from<br />

Florence’s Villa Bardini, Walter Guadagnini, cocurator<br />

of the exhibition Fotografe! Women<br />

photographers, Alinari Archives to Contemporary<br />

Perspectives, shared insights on the show’s<br />

protagonists. Here is Walter’s take on three<br />

Dcreative women and their time.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 7

Above: ‘Fotografe!’ exhibition at Florence’s Villa Bardini, (Image: Olga Makarova).<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY, FINE ART?<br />

The idea of photography reaching fine-art status<br />

has always been a big issue for photographers,<br />

and I believe this dilemma has finally reached its<br />

resolution. Pictorialism, a movement that started<br />

towards the end of the nineteenth century,<br />

addressed this quest, as photographers strove to<br />

ensure that their medium would eventually be<br />

considered a Fine Art, on a par with painting and<br />

sculpture. Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879)<br />

was one of the first photographers ever to create<br />

what is known as the tableau vivant and she can<br />

be considered the mother of Pictorialism – not<br />

only as a ‘female photographer’… as a matchless<br />

creative, independent of her gender.<br />

She used a ‘soft lens’ so her pictures have a<br />

dream-like quality, and brought together groups<br />

of friends and developed certain themes from<br />

Shakespeare’s plays or other literary and religious<br />

works. Oftentimes, she involved members of<br />

Pre-Raphaelite circles or famous personalities<br />

like Lord Alfred Tennyson, astronomer John<br />

Herschel, or poet and playwright Sir Henry Taylor,<br />

whose portrait forms part of the Alinari Archives<br />

collection. In the show, we have the photograph<br />

of a woman, probably an actor, dressed as<br />

Herodias, the mother of Salomé. In other words,<br />

Cameron was engaging in stage photography,<br />

one century before the likes of American artist<br />

8 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Above: The ‘Pictorialism’ section at ‘Fotografe’. Photos by Julia Margaret Cameron, authored from 1865 to 1870, Alinari Archives, Florence, (Image: Olga Makarova).<br />

Cindy Sherman… Her biography is fascinating;<br />

she received her first camera later in life in 1863<br />

– as a 48-year-old woman, not a young girl, and<br />

she became famous almost immediately. She<br />

exhibited in the Victoria and Albert Museum<br />

in 1865 – then called the South Kensington<br />

Museum – which purchased 80 of her prints,<br />

as one of the museum’s first acquisitions. In<br />

fact, for two years, her photography studio was<br />

actually inside the Museum!<br />

A GAME OF ‘WHO’S WHO?’<br />

Madame d’Ora’s 1926 portrait, Madame<br />

Schiaparelli, featuring Roman fashion designer<br />

Elsa Schiaparelli and her dog, epitomises the<br />

typical cannons of the period, which were still<br />

significantly influenced by Pictorialism. She is<br />

almost blurred… only her gaze is in focus. This<br />

technique gives the picture a timeless quality.<br />

Schiaparelli (1890–1973) was a rival of Coco Chanel<br />

and she took the fashion world by storm, in the<br />

inter-war period, with her surrealist creations<br />

[and the invention of the shade ‘shocking pink’ in<br />

1937, a colour borrowed, years later, for Marilyn’s<br />

strapless number in Gentleman Prefer Blondes.<br />

Despite her sedate appearance in Madame<br />

D’Ora’s photograph, Schiaparelli, created cuttingedge,<br />

mostly surrealist garments and accessories,<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 9

MADAME D’ORA (1881–1963)<br />

was a Viennese photographer<br />

intent on immortalising the rich<br />

and famous. Josephine Baker,<br />

Tamara de Lempicka and Collette<br />

are just a few of the women<br />

she captured on camera. Until<br />

1925, she worked in Germany<br />

and Austria in tandem with her<br />

partner Arthur Benda, in a studio<br />

they called Benda-D’Ora.<br />

Exact authorship of the<br />

photographs the studio produced<br />

is difficult to determine, and<br />

it should be noted that Benda<br />

kept ‘D’Ora’ as part of the<br />

company name, even after the<br />

pair separated in 1927, despite<br />

Madame D’Ora having founded a<br />

Paris atelier two years earlier. Her<br />

Parisian studio remained open<br />

until Germany occupied the<br />

city, in 1940, at the height of the<br />

Second World War, after which<br />

Madame D’Ora, of Jewish descent,<br />

went into semi-hiding.<br />

10 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

like those born from her creative partnership<br />

with avant-garde artist Salvador Dali].<br />

The Alinari picture is also an example of the<br />

period’s fashion photography, as fashion has<br />

always been one of the most important ways of<br />

spreading the medium throughout the world. It’s<br />

not an exaggeration to say that photography’s<br />

most famous exponents made their name in the<br />

world of fashion, not least, thanks to the renown<br />

of celebrity sitters.<br />

MOVEMENT AND … MUSIC<br />

Wanda Wulz (1903–1984) is often discussed as a<br />

major exponent of Futurism, but her ties to the<br />

movement were short-lived. For most of her<br />

life, she was a studio photographer, who did not<br />

subscribe to a specific movement. Her interest in<br />

Futurism – or its interest in her – developed in<br />

the early 1920s. The movement was founded by<br />

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti – who Wanda knew<br />

and photographed with great skill. Futurism<br />

celebrated modernity and speed, in addition to<br />

militarism and the glories of warfare.<br />

It was the first avant-garde movement strictly<br />

related to photography. We have to remember that<br />

theatre director and cinematographer Anton Giulio<br />

Bragaglia wrote his Fotodinamismo Futurista in<br />

1914. The Cubists and the Expressionists were not<br />

interested in photography… they were suspicious<br />

of it, because it was considered too mechanical.<br />

Wanda often worked with double exposures, and<br />

many of her shots have a mechanical feel, where<br />

she portrays the idea of movement, because,<br />

Left: Wunder-bar, 1930 c.,<br />

Alinari Archives, Florence.<br />

Above: Portrait of Marion Wulz by Wanda<br />

Wulz. Alinari Archives, Florence.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 11

Above: Marion Wulz in the dress by Anita Pittoni, Wanda Wulz, 1935 c.,<br />

Alinari Archives, Florence.<br />

Above, right: Portrait of Henry Taylor by Julia Margaret Cameron.<br />

Alinari Archives, Florence.<br />

Right: Exercise, Wanda Wulz, 1932, Alinari Archives, Florence.<br />

12 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

y now, we are in the ‘machine era’. One of the<br />

reasons I find photography so interesting is that<br />

it is intrinsically related to societal trends. When<br />

you look at a photograph, you are actually looking<br />

at what is happening in society.<br />

Wanda Wulz was modern in other ways as well.<br />

Women protagonists appear often in her work<br />

– they are gymnasts, Olympians and dancers…<br />

active women. In Jazz band, from 1932, she is<br />

referencing music from the United States, and<br />

you can imagine, in the 1930s, high-society<br />

Europeans were not very friendly towards it…<br />

This photograph is a declaration of modernity,<br />

not least because the player is a woman. We have<br />

many female drummers today, but in Wulz’s time<br />

that would have been a novelty – new music, and<br />

new musicians! RC<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 13

Above: Portrait of Julia Margaret Cameron,<br />

Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, 1870,<br />

MET Museum, New York.<br />

Inset, right: Annie, Julia Cameron, 1864,<br />

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.<br />

14 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

“A tender ardour”<br />

Julia Margaret Cameron<br />

By Linda Falcone<br />

Calcutta-born British photographer Julia<br />

Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was about<br />

my age when she received her first<br />

camera at 48 – as a gift from her daughter and<br />

son-and-law. It was a suitable present, they<br />

thought, for a woman who needed quite a lot to<br />

keep her occupied. She had<br />

raised five of her relatives’<br />

children and had five of<br />

her own – in addition to<br />

adopting a young Irish girl,<br />

whom she found begging on<br />

Putney Heath. The gift was<br />

“to amuse you, Mother, to try<br />

and photograph during your<br />

solitude.”<br />

In her own words, Julia<br />

handled the camera with<br />

“tender ardour” from the<br />

time she shot what she<br />

referred to as her “first<br />

success” in 1864 – the<br />

photo of a girl called Annie<br />

Philpot, which she purposely<br />

blurred to suggest the child’s<br />

movement, rather than<br />

seeking the usual stoic pose Victorians imposed<br />

upon photographed children.<br />

Julia would transform her estate’s henhouse<br />

into her first darkroom, which she called the ‘glass<br />

house’ and used it to produce dreamy pictures<br />

that photographers hated and artists loved.<br />

Cameron’s only natural daughter – also named<br />

Julia – was right about the gift being an antidote<br />

to solitude. The whole world – or at least the<br />

whole Isle of Wight – was coaxed or commanded<br />

in front of her camera. House workers or hapless<br />

tourists admiring the beach<br />

were somehow lured back<br />

to her ‘lair’ to pose for a<br />

tableau scene, transformed<br />

into characters born in the<br />

mind of Milton. They would<br />

become the Greek poet<br />

Sappho or King Lear’s sad<br />

daughters. The neighbour’s<br />

hired help was dolled up<br />

and made to carry the<br />

Madonna’s Annunciation<br />

lily. Strapped-on swan wings<br />

were a common feature in<br />

her photographs. And in the<br />

buzz and glory of it all, she<br />

treated genius scientists<br />

and humble seamstresses<br />

exactly the same.<br />

Lucky for us, the Isle<br />

of Wight was brimming with the vacationing<br />

elite, which secured for posterity some of the<br />

most important portraits of nineteenth-century<br />

British writers, scientists and poets ever taken.<br />

Poet Alfred Tennyson asked Julia to photograph<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 15

Above: Vivien and Merlin<br />

(sitters Agnes Mangles, Charles<br />

Hay Cameron) Julia Margaret<br />

Cameron, 1874, Victoria<br />

and Albert Museum Library,<br />

London.<br />

Above, right: King Lear<br />

allotting his kingdom to<br />

his three daughters, Julia<br />

Margaret Cameron, 1872, MET<br />

Museum, New York.<br />

a series to accompany his poem cycle Idylls of<br />

the King and this literary association pleased her<br />

and gave added credence to her quest, namely, to<br />

bring photography out of the technical realm, by<br />

elevating it to the level of the other arts.<br />

Tennyson did not escape her lens, of course –<br />

she made him pose too, once as himself, and other<br />

times – as whomever she saw fit. A description<br />

of Tennyson’s sittings features in Freshwater, the<br />

comic sketch Virginia Woolf wrote for a private<br />

performance at Bloomsbury. Woolf’s mother, Julia<br />

Jackson, was Cameron’s niece and posed for<br />

many pictures as well. Woolf’s character ‘Julia’<br />

snaps at ‘Tennyson’ with characteristic intensity,<br />

“That’s the very attitude I want! Sit still, Alfred!”<br />

Tennyson describes his experience: “The<br />

studio, I remember, was very untidy and very<br />

uncomfortable. Mrs Cameron put a crown on my<br />

head and posed me as the heroic queen. … The<br />

exposure began. A minute went over and I felt as if<br />

I must scream, another minute and the sensation<br />

was as if my eyes were coming out of my head;<br />

a third, and the back of my neck appeared to<br />

be afflicted with palsy; a fourth, and the crown,<br />

which was too large, began to slip down my<br />

forehead; a fifth—but here I utterly broke down,<br />

for Mr Cameron, who was very aged, and had<br />

unconquerable fits of hilarity which always came<br />

in the wrong places, began to laugh audibly, and<br />

this was too much for my self-possession, and I<br />

was obliged to join the dear old gentleman.”<br />

Julia had met Charles Hay Cameron in South<br />

Africa, and married him in India, in 1838. Fifteen<br />

years his wife’s senior, he was man enough<br />

to play Merlin in the artist’s scenes, and any<br />

woman whose husband is smart enough to make<br />

her want to run through the house with fresh<br />

photographs in tow, so that he could receive<br />

them with guaranteed ‘delight’ is a woman I want<br />

to meet in the elevator. “It is my daily habit to run<br />

to him with every glass upon which a fresh glory<br />

is newly stamped,’ she wrote “and to listen to<br />

his enthusiastic applause. This habit of running<br />

into the dining-room with my wet pictures has<br />

stained such an immense quantity of table linen<br />

with nitrate of silver, indelible stains, that I should<br />

16 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

have been banished from any less indulgent<br />

household.”<br />

Cameron’s first show was held in 1865 at the<br />

South Kensington Museum – now the Victoria<br />

and Albert Museum – which, surprisingly,<br />

was also home to her photography studio in<br />

1868. Apparently, the well-connected woman<br />

knew how to get a gig. In fact, although she<br />

did not photograph on commission and never<br />

established a professional studio, she did market,<br />

print and sell her images through Colnaghi, and<br />

the V&A now owns 80 of her pictures, purchased<br />

in the early days of her 12-year career.<br />

In 1875, the Camerons moved to Sri Lanka, then<br />

Ceylon, to tend to a fungus affecting their coffee<br />

plantations. Julia Cameron died there, four years<br />

later, with thousands of photos to her credit.<br />

Photographic materials were scarce in Ceylon,<br />

and her later production diminished, but her<br />

inborn mission – discovered late, and lived with<br />

all the fire of her temperament, would never leave<br />

her. “Beauty, you are under arrest, I have a camera<br />

and am not afraid to use it,” has remained as one<br />

of her most frequently quoted phrases, hence, it<br />

is fitting that “Beauty” was her dying word.<br />

With images of Julia, ‘Merlin’ and crowned<br />

Mr Tennyson, still fresh in our minds, I’d like<br />

to share a final quote, for I would be remiss if<br />

amidst the humour, I neglected to emphasise the<br />

seriousness of Julia’s photographic endeavours.<br />

Victorian critics had ever-harsh words for her.<br />

Photographers derided her ‘soft-focus’ images as<br />

amateurish and her medievalist scenes as reason<br />

for ridicule, yet she approached her work with<br />

religious dedication. Carlyle, Dickens, Darwin,<br />

Herschel, Browning, Watts and more have Julia<br />

Margaret Cameron to thank, for how they are<br />

remembered in the collective consciousness, and<br />

here’s why: “When I have had such men before<br />

my camera,” the photographer wrote, “my whole<br />

soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards<br />

them in recording faithfully the greatness of the<br />

inner as well as the features of the outer man.<br />

The photograph thus taken has been almost the<br />

embodiment of a prayer.”<br />

Amen, dear Julia Margaret Cameron. Amen. RC<br />

Above, left: Maud (sitter Mary<br />

Hillier), Julia Cameron, 1875,<br />

Victoria and Albert Museum<br />

Library, London.<br />

Above: Angel of the Nativity<br />

(Sitter Laura Gurney), Julia<br />

Margaret Cameron, 1872,<br />

J. Paul Getty Museum,<br />

Los Angeles.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 17

Edith Arnaldi<br />

A ‘woman of the future’ found in Alinari<br />

Archives<br />

By Linda Falcone<br />

Edith Arnaldi – celebrated in Futurist circles<br />

as Rosa Rosà – was a Futurist painter, writer,<br />

illustrator and ceramicist, yet few know that<br />

she was also a dedicated photographer, whose<br />

largely undiscovered oeuvre – comprising<br />

negatives, glass slides and prints – is 10,000<br />

works strong. Florence-based German researcher<br />

Lisa Hanstein, who has studied Arnaldi over the<br />

course of two decades, only recently discovered<br />

the artist’s ‘photographic vein’, thanks to her<br />

copious archive at Florence’s Alinari Foundation<br />

for Photography. As contributor to the short-lived<br />

Florence journal Italia Futurista, Arnaldi (1884-1978)<br />

stood at the forefront of early feminism in Italy,<br />

generating debate among her contemporaries,<br />

authoring essays such as ‘Women of the Future’<br />

and ‘Women Are Finally Changing’, in which she<br />

analysed and advocated for new, anti-bourgeois<br />

roles for women, an issue made even more<br />

relevant once a whole generation of men left for<br />

the front, to fight the Great War.<br />

WOMEN IN THE ROUND<br />

“Over the last few years, my studies on Edith<br />

Arnaldi have focused on her interest in the<br />

invisible – her portrayal of moods and states<br />

of mind. Despite Arnaldi being a prolific artist,<br />

almost none of her paintings and ceramic works<br />

have survived or been traced, therefore, to find<br />

such a large photographic oeuvre in Florence is<br />

exciting. It is also a revelation to find that much of<br />

Arnaldi’s photography captures fleeting moments<br />

in the lives of women. They are pensive or<br />

enthusiastic; they are engrossed in their work…<br />

and most importantly, they are represented as<br />

individuals,” says Dr. Hanstein. “The visual arts<br />

in Arnaldi’s time followed trends advocated by<br />

Istituto LUCE – the Union for Education Cinema<br />

– a major media-arm of the Fascist regime, which<br />

strove to represent certain typecast characters,<br />

and well-established stereotypes. Although<br />

Arnaldi’s photography in the thirties and forties<br />

portrays rural living in Italy’s hillside towns, which<br />

include glimpses of traditional festivals and ageold<br />

customs, you get a sense that the people<br />

her camera captures are never flat characters<br />

– they are real, multi-faceted people, as in her<br />

Ciociaria works. The ‘Water-bearer’, whom she<br />

photographed over the course of several years, is<br />

representative of her sensibility.”<br />

Right: At Edith’s villa, 1951,<br />

Edith Arnaldi, Alinari Archives,<br />

Florence.<br />

18 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 19

Above, left: Somalia, 1951,<br />

Edith Arnaldi, Alinari Archives,<br />

Florence.<br />

Above, right: Piglio [Inv<br />

NVQ-S-002281-4617], 1935,<br />

Edith Arnaldi, Alinari Archives,<br />

Florence.<br />

“We should also note,” Hanstein continues, “that<br />

Arnaldi was not working on commission. She<br />

came from an aristocratic family, and her pictures<br />

were not her livelihood. This meant she could<br />

dedicate a lot of time to experimentation and<br />

work with subjects entirely of her own choosing.<br />

The fact that Arnaldi was an avid traveller<br />

is significant. Her daughter Maretta (Maria<br />

Enrichetta), who married an Italian ambassador,<br />

lived in Madrid (1935-6), Rabat (1938) and Somalia<br />

(1951), and Arnaldi would visit her, sometimes for<br />

months – a daunting journey during her time.<br />

Her Somalia pictures – especially those of village<br />

women – have a similar intimate feel to those<br />

in her Ciociaria series.” The anthropological<br />

nature of Arnaldi’s body of work sheds light on<br />

other parts of the world as well, as she travelled<br />

frequently, from the 1930s to the 1950s – to<br />

Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Germany<br />

and Egypt, among other nations.<br />

AN AURA, A VOCATION<br />

“Scientific photography was very important to<br />

some painters of Italian futurism and, in the first<br />

half of the 1900s, artists started playing with the<br />

idea of using scientific discoveries to define and<br />

inspire their own artistic research, because it<br />

zeroed in on what the naked eye could not see,”<br />

Dr Hanstein explains. As early as 1917, Arnaldi was<br />

interested in scientific photography, and she may<br />

have ultimately turned to the artistic medium<br />

because it could do things that painting and<br />

drawing could not.”<br />

A number of Futurist artists, including Arnaldi,<br />

were impressed by research on paranormal<br />

phenomena leading to the discovery of<br />

magnetism, and the detection of the aura,<br />

for instance, or concentrated their efforts on<br />

what Futurism painter and poet Giacomo Balla<br />

described as, “representing light by separating<br />

the colours that compose it.” Balla, the oldest<br />

20 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

exponent of the Futurists who, incidentally called<br />

themselves ‘the Lords of Light’, was known to wear<br />

a light bulb wrapped in transparent celluloid to<br />

light up his neckties and, in accordance with the<br />

manifesto of the Futurist painters, he maintained<br />

that the eyes of the artist were like an x-ray<br />

that could see things that others couldn’t. “The<br />

vocation of the artist, in the Futurists’ view, was to<br />

make hidden elements visible,” Hanstein explains,<br />

“and, obviously, this view was closely tied to the<br />

occult philosophies in vogue in Europe at the<br />

time, not least Austria, where Arnaldi was raised<br />

and educated.”<br />

‘SEDUCTION’ AND THE NEW WOMAN<br />

“Marinetti called Arnaldi the ‘genius from<br />

Vienna’, and they knew each other, but she did<br />

not cultivate close ties with him,” Dr. Hanstein<br />

notes. “A significant collection of letters penned<br />

by Arnaldi’s hand is yet to be found, but two of<br />

her letters to writer Emilio Settimelli form part of<br />

the Fondazione Primo Conti Museum archive in<br />

Fiesole. ‘I heard Marinetti is going to marry, do<br />

you know who?’ Arnaldi writes, and the question<br />

demonstrates her relationship with the founder<br />

of Futurism was not especially close, despite her<br />

name appearing in his notebooks. The artist’s<br />

letter reveals her sense of humour, and you<br />

get the sense of what she is actually asking:<br />

‘Who would marry Marinetti?’ The answer, of<br />

course, was Benedetta Cappa, an artist and, later,<br />

a major exponent of the movement Marinetti<br />

championed.”<br />

How the women of Marinetti’s circle morphed<br />

the pillars of his Manifesto Futurista into<br />

something that eventually led to their ‘liberation’,<br />

is not evident at first glance. “We want to glorify<br />

war, the only cure for the world – militarism,<br />

patriotism, the destructive gesture of the<br />

anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and<br />

contempt for woman,” Marinetti wrote in the 1909<br />

document that defined the movement.<br />

Below: Piglio [Inv<br />

NVQ-S-002281-4527], 1935,<br />

Edith Arnaldi, Alinari Archives,<br />

Florence.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 21

Futurist women appear to have taken this<br />

contempt, in stride, and perhaps interpreted it as<br />

a contempt for the limited nature of traditional<br />

female roles. In fact, they shared his disdain<br />

for both the Angel of the Hearth and Femme<br />

Fatale. “Although Arnaldi was a resident of Rome,<br />

she presumably had contact with her female<br />

counterparts living in both Rome and Florence…<br />

Mina Loy, Irma Valeria, Maria Ginanni and Fulvia<br />

Giuliani, and their debate on the role of the New<br />

Woman, was an important one, but we have to<br />

remember, they did not all agree on what ‘la<br />

nuova donna’ meant, or how the change should<br />

play out exactly. They simply shared the need for<br />

a new image.”<br />

Edith Arnaldi, you might say, was a woman of<br />

two names and many souls – at least three – as<br />

the title of her novel A Woman with Three Souls<br />

appears to suggest. Authored in 1918, her novel is<br />

an early example of feminist science fiction, and<br />

considered a tit-for-tat reaction to Marinetti’s only<br />

successful book, How to Seduce Women, printed<br />

in 1916. According to Arnaldi, she did not consider<br />

herself a feminist but as ‘–ist’, hence, she says, ‘the<br />

first part of the word has not yet been found’”. Dr<br />

Lisa Hanstein, for one, is still searching for the<br />

word… or words… that will make a perfect fit. RC<br />

For more on the Digital Archive on Futurism in Florence at the<br />

Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut: http://<br />

futurismus.khi.fi.it/index.php?id=100&L=1<br />

Above, left: Geometric conflagration, 1917, L’Italia futurista, Edith Arnaldi (von Haynau or Rosa Rosà),<br />

Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz.<br />

Above, right: Dancer, 1921, Edith Arnaldi (von Haynau or Rosa Rosà), Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz.<br />

Above: Display case featuring Edith Arnaldi’s gelatin silver prints with notes (1936) Alinari Archives,<br />

Florence, (Image: Olga Makarowa).<br />

22 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

D<br />

r. Lisa Hanstein received her PhD at<br />

the Goethe University Frankfurt in<br />

2015. She is Academic Assistant in the<br />

library at the Kunsthistorisches Institut<br />

in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut. She<br />

co-organised ‘Mapping Futurism’, the<br />

conference proceedings and digital<br />

projects on Futurism. Hanstein is the<br />

author of several books and essays,<br />

including the in-English publications:<br />

Edyth von Haynau, Edyth Arnaldi and<br />

Rosa Rosà: One Woman, Many Souls<br />

(2021) and Edyth von Haynau: A Viennese<br />

Aristocrat in the Futurist Circles of the<br />

1910s (2015).<br />

She specialises in the impact of<br />

psychology, spiritism and science on<br />

Italian Futurist art and has published<br />

articles on the topic, as well as on<br />

Edith Arnaldi and on the KHI’s Futurism<br />

Archive. Her work on Edith Arnaldi, in<br />

the Alinari Archives with co-curator<br />

Emanuela Sesti, was paramount to the<br />

Fotografe! exhibition (See page 7).<br />

Top: The ‘Edith Arnaldi’ section at ‘Fotografe!’ at Forte di Belvedere,<br />

featuring Arnaldi’s Ciociaria series, (1935), (Image: Olga Makarowa).<br />

Above: Co-curator Emanuela Sesti oversees exhibition set-up, June <strong>2022</strong>.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 23

24 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Alinari Reception<br />

A celebratory send-off<br />

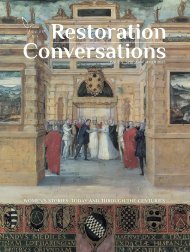

On September 27, <strong>2022</strong>, Calliope Arts gathered with<br />

its partners and friends to celebrate the successful<br />

conclusion of the show FOTOGRAFE! Women<br />

photographers: Alinari Archives to Contemporary Perspectives.<br />

Villa Bardini, one of the exhibition’s venues – together with Forte<br />

di Belvedere – provided an evocative backdrop to the festivities,<br />

which brought together our growing network of like-minded<br />

individuals, committed to the art-and-culture scene in Florence<br />

and further afield. The show, curated by Emanuela Sesti and<br />

Walter Guadagnini, ran from June 18 to October 2, <strong>2022</strong>. Presented<br />

and promoted by the Alinari Foundation for Photography and the<br />

Fondazione CR Firenze, in collaboration with the Municipality of<br />

Florence, it saw the participation of donors Calliope Arts.<br />

Through its grants programme, Calliope Arts funded the<br />

creation of two exhibition sections devoted to significant<br />

collections from the Alinari Archives: that of the sisters Wanda<br />

Wulz (Trieste 1903-1984) and Marion Wulz (Trieste 1905-1990) and<br />

that of Edith Arnaldi (Vienna 1884-Rome 1978). “We are especially<br />

interested in photography by women because it is an art form<br />

that has always been relatively accessible to women, unlike the<br />

more traditional fine arts,” says Calliope Arts President Margie<br />

MacKinnon, “The explosion of popularity of photography<br />

coincided with the expansion of women’s freedom to be active<br />

in public spheres and women’s demands for more independence<br />

and recognition. Thus, this exhibition’s creativeness brought<br />

dynamism, experimentation, and new techniques to the fore. We<br />

have been delighted to see these pioneers and contemporary<br />

women in the exhibition spotlight. It has been an enriching<br />

partnership, which we hope will continue in the future.”<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 25

26 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Previous page: Views of Villa Bardini. Photos by<br />

Federica Narducci<br />

Left, top: E. Pavesi, Vice Mayor of Monzuno,<br />

RC managing editor L. Falcone, Calliope Arts<br />

founders W. McArdle and M. MacKinnon,<br />

co-curator E. Sesti and publisher F. Richards.<br />

Bottom left: D. Bolognini with The Florentine<br />

co-owner G. Giusti.<br />

Bottom right: Scholar C. Tobin, Violinist<br />

R. Palmer and archaeologist B. Leigh.<br />

Right, top: Atelier degli Artigianelli’s B. Cuniberti<br />

with artist V. Slichter.<br />

Right, middle: Conservator R. Lari and<br />

Il Palmerino’s V. Parretti.<br />

Right, bottom: Calliope Arts co-founder<br />

W. McArdle with artist R. Stavropoulos and<br />

husband G. Maragno.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 27

28 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Clockwise from top left: US Consul General R. Gupta,<br />

W. McArdle and UK collector C. Levett,<br />

Vice President of AADFI G. Bonsanti with L. Falcone,<br />

B. Balducci and Accademia Gallery director C. Hollberg,<br />

Casa Buonarroti president C. Acidini with Rosalia Manno,<br />

director of the Archives for the Memory and Writings of Women,<br />

Alinari Foundation for Photography: Director C. Baroncini,<br />

President G. Van Straten, Press coordinator C. Briganti,<br />

US philanthropists D. and C. Clark.<br />

This page, top: Front-row guests: Accademia Gallery director<br />

C. Hollberg, British Institute of Florence director S. Gammel,<br />

Il Palmerino’s V. Parretti, US Consul R. Gupta, Conservator<br />

E. Wicks and husband C. Marino.<br />

Opposite: Photographers A. Barrucchieri and<br />

A. Tommasi from Il Cupolone, S. Pretsch, Fondazione Lisio.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 29

Enjoying the show:<br />

This page, left: V. Parretti with photographer J.M. Cameron.<br />

Centre : D. Bolognini with M. Meloni’s pictures.<br />

Below: C. Bartolini, C. Tobin and conservator A. Gavazzi in room<br />

featuring F. Belli’s works.<br />

Right, top: Guests share a laugh with co-curator E. Sesti.<br />

Right, below: Santa Maria Nuova Foundation secretariat and<br />

president C. Bartolini and G. Landini.<br />

30 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 31

32 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Artemisia’s<br />

descent<br />

Project donors hold their breath as<br />

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of<br />

Inclination (1616) is removed from the Casa<br />

Buonarroti Museum’s ceiling on Day 1 of<br />

the ‘Artemisia UpClose’ restoration project,<br />

in October <strong>2022</strong>. Once the painting is<br />

safely ‘grounded’, its patrons share their<br />

first impressions.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 33

34 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Previous page: Donors Margie<br />

MacKinnon, Wayne McArdle<br />

and Christian Levett, Project<br />

donors and management watch<br />

Artemisia’s descent at Casa<br />

Buonarroti.<br />

Left: Conservator Elizabeth Wicks<br />

at work.<br />

Above: Donor Margie MacKinnon<br />

with the Inclination.<br />

MARGIE MACKINNON<br />

“I was surprised at what a moving experience<br />

it was. This project has been months in the<br />

making, so while this was the first moment of<br />

the restoration, it was not the first moment of<br />

the project. Watching the painting coming down,<br />

your heart is in your mouth… because you are<br />

desperate that nothing is going to go wrong. Now<br />

that I see the canvas and can stand in front of<br />

it, what really excites me is knowing how many<br />

people are going to get to see this painting up<br />

close. When the conservation is finished, it will<br />

go back onto the ceiling where it lives, but during<br />

the time it is being restored and exhibited, people<br />

are going to have such a wonderful opportunity<br />

to see and appreciate this amazing work.”<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 35

Below: Donor Wayne McArdle shares<br />

first impressions.<br />

Right: Artemisia’s painting is<br />

removed from Gallery ceiling<br />

framework.<br />

WAYNE MCARDLE<br />

“Seeing the painting’s descent was a very<br />

emotional moment! What surprised me was how<br />

lightly the frame of the painting was placed on the<br />

ceiling. I expected there would be some chipping<br />

away at paint, or adhesive or something… nails<br />

or screws, but no! They just lifted the painting<br />

lightly off the frame, and brought it down from<br />

the ceiling, very, very gently. Of course, once<br />

down, it was simply wonderful to see the work. I<br />

think we were all totally impressed by the quality<br />

of the painting itself. I believe we are going to<br />

see some real revelations when the restoration<br />

and investigation work is finished and, as far as<br />

Calliope Arts and our mission is concerned, I<br />

can’t think of a better way to demonstrate what<br />

we are trying to do, in bringing the work of<br />

women artists to the attention of the public, so<br />

I’m delighted.”<br />

36 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 37

38 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong><br />

CHRISTIAN LEVETT<br />

Firstly, the painting looks to be over five feet<br />

high, so when you see it way above you on the<br />

ceiling, you don’t get a sense of how big the<br />

painting actually is; it just looks like another one<br />

of the panels. The scale of it is impressive, once it<br />

comes down. I think you also get a sense of how<br />

fantastic it’s going to look once the restoration<br />

is completed. Of course, when it is up high, it’s<br />

dark… it has withstood the test of time the last<br />

400 years – because they don’t think it has been<br />

moved during that period.<br />

When you see it up close, you get the feeling<br />

immediately as to what an amazing project this is.<br />

The other fantastic and slightly unexpected thing<br />

is that, as they took it out of the ceiling frame and<br />

brought it down, 400 years of dust fell from the<br />

canvas, and that, in and of itself, was a spectacular<br />

moment. So, a whole array of different things<br />

impressed me… it’s tremendously exciting! RC

Left: Donor Christian Levett<br />

discusses Artemisia UpClose.<br />

Above: Project donors<br />

and management at Casa<br />

Buonarroti: C. Levett, L.<br />

Falcone, A. Cecchi, C. Accidini,<br />

M. MacKinnon, W. McArdle.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 39

Artemisia<br />

UpClose<br />

Many ways to see the mastery<br />

At its inception, and over the course of<br />

many months of planning, we referred<br />

to our wonderful Artemisia Gentileschi<br />

project as ‘Artemisia Unveiled’. This title was<br />

intended as a metaphorical nod to the part<br />

of the restoration project in which we would<br />

use sophisticated diagnostic equipment, such<br />

as infra-red technology, to ‘peek’ beneath the<br />

veil and discover how the painting originally<br />

looked, allowing us to recreate a virtual image<br />

of Artemisia’s work as it would have appeared to<br />

Michelangelo the Younger, who commissioned it.<br />

It was always intended that the restoration of the<br />

painting would leave the veil intact – as it has<br />

become an integral part of the work and its history.<br />

In order to make clear our intentions, with the<br />

descent of the painting into the museum spotlight<br />

and the restoration’s media debut, we have<br />

renamed our project ‘Artemisia UpClose’. This not<br />

only removes the ambiguity of the ‘Inclination’s’<br />

unveiling, it also highlights the fact that this<br />

restoration provides a unique opportunity for the<br />

public to truly view Artemisia’s work up close –<br />

while it is undergoing conservation treatments<br />

and when the restored work is exhibited, along<br />

with the virtual image of ‘what lies beneath the<br />

veil’. In due course, the painting will return to<br />

the ceiling niche for which it was created. While<br />

still on view, it will then be well out of touching<br />

distance.<br />

Right: Diagnostic analysis:<br />

Examining the painting in raking<br />

light ; Artemisia’s Inclination in the<br />

Model Room at Casa Buonarroti.<br />

40 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 41

IN PROGRESS AT THE MUSEUM<br />

OCTOBER <strong>2022</strong> TO APRIL 2023<br />

We’d like Florence and its countless international<br />

visitors and expats to meet Artemisia in person!<br />

Fondazione Casa Buonarroti president, art<br />

historian and author Cristina Acidini, welcomed<br />

the painting – which has never been in the public<br />

eye at such close range before – by sharing her<br />

initial impressions: “It was very exciting to have<br />

the opportunity to examine the canvas close<br />

up. Underneath the altered varnish, we can see<br />

that the painting is of extremely high quality.<br />

We know that Artemisia was an extraordinary<br />

painter and the Inclination confirms it. If you<br />

look at the softness of the skin, the tenderness<br />

of her forms, the figure’s luminosity and even her<br />

very complex hairstyle – all of these elements are<br />

sure to prove very interesting once its complete<br />

legibility is achieved.”<br />

During museum opening hours, the artloving<br />

public will have the opportunity to see<br />

the Allegory of Inclination restoration project<br />

in progress, thanks to a worksite set up in Casa<br />

Buonarroti’s ‘Model Room’. Head conservator<br />

Elizabeth Wicks will be available to answer<br />

questions from the public, on Fridays. Those who<br />

will not be able to make it to Florence in person<br />

can count on getting a glimpse of the process,<br />

thanks to a series of short videos created by<br />

Florence-based filmmaker Olga Makarova. The<br />

first segment, ‘Artemisia, The Descent’ has already<br />

gone viral on social media. For more on the<br />

science-side of the restoration, see page 52.<br />

EXHIBITION AND PUBLICATION PLANS<br />

SEPTEMBER 2023 TO JANUARY 2024<br />

“Artemisia UpClose will transform into a future<br />

exhibition at Casa Buonarroti, scheduled for next<br />

September,” says museum director Alessandro<br />

Cecchi, who is overseeing the project, together<br />

with Jennifer Celani, official for the Archaeological<br />

Superintendence for the Fine Arts and Landscape<br />

for the metropolitan city of Florence. Although<br />

full exhibition details are still in the development<br />

phase, Dr. Cecchi shares the following, “The show<br />

will spotlight conservation findings and explore<br />

the context surrounding the painting’s creation,<br />

including the significance of her Florentine<br />

debut and her key relationships with Grand Duke<br />

Cosimo de’ Medici and the city’s cultural milieu.”<br />

Again, those unable to see the show in person,<br />

can still have a keepsake from the exhibition:<br />

the English language exhibition catalogue (The<br />

Florentine Press, 2023) will be finalised next<br />

summer, and later, flanked by the Italian language<br />

publication ‘Buonarrotiana’ series (2023 edition)<br />

featuring specialist studies on Artemisia and<br />

her time, followed by a lecture series with major<br />

scholars in response to the show.<br />

Right, top left: Conservator Elizabeth Wicks uses<br />

a digital microscope to examine<br />

the painting’s condition.<br />

Right, top right: Conservator examines<br />

re-painting by Il Volteranno.<br />

Right: Phase-1 diagnostics,<br />

Artemisia UpClose.<br />

42 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 43

44 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

TENDER LOVING CARE FOR CASA<br />

BUONARROTI<br />

While the Allegory of Inclination is at the heart<br />

of the project, its restoration is by no means<br />

the only initiative forming part of ‘Artemisia<br />

UpClose’. “We’d like to look at the project as<br />

the start of something bigger,” says project codonor<br />

Christian Levett. Beyond the restoration<br />

of Artemisia’s Buonarroti painting, the project<br />

includes a refurbishment of the museum entrance,<br />

the renewal of its signage, and the redesign of<br />

the Gallery room’s lighting. This museum has an<br />

amazing story to tell, and we want to shed more<br />

light on it—literally.” This ‘tender-loving-care’ for<br />

the gallery will be completed by the end of 2023,<br />

and enhance the visitor experience, particularly<br />

of the seventeenth-century wing, a treasure trove<br />

designed by Michelangelo the Younger over the<br />

course of 30 years, whose genius conceived the<br />

first-ever architectural and artistic tribute to an<br />

artist, his great uncle, ‘Michelangelo the Divine’.<br />

WHO’S INVOLVED?<br />

The project, funded by Calliope Arts and<br />

Christian Levett (see page 38), is curated by<br />

Fondazione Casa Buonarroti and overseen by<br />

the Archaeological Superintendence for the Fine<br />

Arts and Landscape for the metropolitan city of<br />

Florence. It brings together restoration scientists,<br />

technicians, photographers and filmmakers to<br />

compile, analyse, document and share findings.<br />

Its players include: Head conservator Elizabeth<br />

Wicks, Italy’s National Research Council (CNR)<br />

and National Institute for Optics (NIO), Teobaldo<br />

Pasquali for X-ray and radiographs, Ottaviano<br />

Caruso for diagnostic images; Massimo Chimenti<br />

of Culturanuova s.r.l. for digital image creation;<br />

Olga Makarova for video and reportage<br />

photography. Project Coordinator: Linda Falcone.<br />

Media partners: Restoration Conversations and<br />

The Florentine. RC<br />

Left: Detail of the painting, pre-restoration, showing<br />

upclose Artemisia’s brushstrokes.<br />

Above, top: Cleaning handmade paper layer glued to<br />

revervse of canvas.<br />

Above: Painting facedown with original canvas nailed<br />

to corner of stretcher. Layer of canvas and paper glued<br />

to the reverse.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 45

A veiled issue<br />

The hows and whys behind Artemisia’s veil<br />

THE POEM AND THE PREMISE<br />

In 1846, Robert and Elisabeth Browning secretly<br />

eloped to Florence, one week after their London<br />

wedding, and settled in Casa Guidi, which<br />

Elizabeth described as being “six paces from<br />

the Piazza Pitti”. In the Tuscan capital, Elisabeth<br />

quipped, “we should live like the Grand Duke with<br />

five hundred a year” – which was lucky, since her<br />

father had all but disowned her for marrying<br />

Robert. They lived mostly in Florence for 15 years,<br />

until her death, and it was there she published a<br />

novel in verse, Aurora Leigh – her longest work<br />

– in 1857. Florence would provide inspiration<br />

to Robert as well, and his sometimes derisive<br />

and often humorous pen gave a voice to those<br />

who once dwelled in Florence’s palazzi – even<br />

after he had stopped living in one. In his final<br />

volume of poems, Asolando: Fancies and Facts –<br />

published in Venice on the day of his death in<br />

1889 – he includes “Beatrice Signorini”. Browning<br />

thought the poem the best in the book – told<br />

by an ‘external narrator’ in many ways similar to<br />

himself.<br />

In “Beatrice Signorini”, Artemisia Gentileschi<br />

is portrayed as “a wonder of a woman, and no<br />

Cortona drudge”. She is cast as the lover of<br />

Baroque painter Francesco Romanelli, a Viterboborn<br />

moderately successful painter. Their<br />

romance is fictional, but the jealousy the poem<br />

conveys is real. As the story goes, Artemisia<br />

produced a Florence picture: “a semblance of<br />

her soul, she called ‘Desire’” painted to “brighten<br />

Buonarroti’s house”. The Inclination, which<br />

Browning never mentions by name, presides over<br />

a room “where the fire sits”.<br />

The poet’s imaginary narrative continues, and<br />

Romanelli’s wife – the poem’s namesake – takes<br />

revenge on a portrait her husband painted of<br />

Artemisia. By contrast, the allegorical figure “with<br />

starry front as guide”, authored by Gentileschi’s<br />

own hand, remains unharmed. “If you see<br />

Florence, “pay that piece your vows”, the narrator<br />

urges, before launching into a poetic tirade that<br />

alludes to a real-life scenario still relevant to<br />

the art world today: the addition of Artemisia’s<br />

46 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Right: Allegory of Inclination,<br />

Artemisia Gentileschi, 1616,<br />

Casa Buonarroti Museum,<br />

Florence, pre-restoration,<br />

(Image: Ottaviano Caruso).<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 47

Left: Portrait of Robert Browning, Herbert Rose Barraud,<br />

1888 c. The Roy Davids Collection, London.<br />

Above: Elisabeth Barrett Browning, Michele Gordigiani,<br />

1859, National Portrait Gallery, London.<br />

Right: Self portrait of Baldassarre Franceschini,<br />

Il Volterrano, 1636-1646, The Glories of the House of<br />

Medici, Villa della Petraia, Florence.<br />

48 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

veil and drapery. Browning blames the Grand<br />

Duke’s prudish superintendent – whom the poet<br />

targets in more than one work: “The blockhead<br />

Baldinucci’s mind, imbued / With monkish morals,<br />

bade folk Drape the nude / And stop the scandal!”<br />

In his own six-volume work, ‘Notes on Teachers<br />

of Drawing from Cimabue until Now’, Filippo<br />

Baldinucci (1665-1717), a post-Vasari art historian<br />

and biographer, reports that on the instruction<br />

of Lionardo Buonarroti, he asked Volteranno to<br />

spare the blushes of women and children, by the<br />

addition of a flowing veil over the lower part of<br />

the painting. This order, made “for the decorum<br />

and modesty” of the Buonarroti home, “filled with<br />

young ones, his children… and his wife” made the<br />

ink in Browning’s pen boil: “Hang his book and<br />

him!” he wrote.<br />

Although Baldinucci takes the literary brunt of<br />

Browning’s disdain, it is not likely the biographer<br />

had the power to sway Lionardo Buonarroti one<br />

way or the other, as Hawklin and Meredith point<br />

out (2009). What we can say is that censoring<br />

nudes was a common practice that generations<br />

of artists of Artemisia’s calibre and beyond had<br />

to grapple with.<br />

The 1684 addition of the veil to the Inclination<br />

was carried out by a painter from the Tuscan<br />

town of Volterra, Baldassare Franceschini (1611-<br />

1689). Noted as a fresco painter, he received<br />

commissions from the Medici family for work<br />

in the Villa Petraia. Franceschini was known<br />

as Il Volterrano (referencing his birthplace) or<br />

sometimes Il Volteranno Giunore, to distinguish<br />

him from an earlier painter from the same town.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 49

Below: Detail, The Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel ceiling,<br />

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1508-1512).<br />

Right: Detail, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco, prerestoration,<br />

with evidence of Il Braghettone’s handiwork.<br />

That painter was Daniele Ricciarelli (1509-1566).<br />

Sadly for Ricciarelli, he was also to become known<br />

as Il Braghettone or ‘the breeches maker’’. This is<br />

because it was Ricciarelli who was engaged by Pope<br />

Pius IV to cover up, with fig leaves and loincloths,<br />

the ‘naughty bits’ of the figures in Michelangelo’s<br />

Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel.<br />

50 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

That painter was Daniele Ricciarelli (1509-1566).<br />

Sadly for Ricciarelli, he was also to become<br />

known as Il Braghettone or ‘the breeches<br />

maker’’. This is because it was Ricciarelli who<br />

was engaged by Pope Pius IV to cover up, with<br />

fig leaves and loincloths, the ‘naughty bits’ of the<br />

figures in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the<br />

Sistine Chapel. Ricciarelli is said to have been<br />

well liked by Michelangelo, and may have done<br />

less damage to Michelangelo’s fresco than other<br />

censors, following Counter-reformation diktats.<br />

When it came to the cleaning and restoration<br />

of the Chapel in 1980, a controversy arose over<br />

whether to leave Il Braghettone’s additions or to<br />

restore Michelangelo’s masterpiece to its original<br />

state. In the end, it was possible to uncover only<br />

a portion of the original work. Luckily, in 1549<br />

the farsighted Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had<br />

commissioned Marcello Venusti to paint an exact<br />

copy of the Last Judgment for posterity, now in<br />

the Capodimonte Museum in Naples.<br />

In the absence of an equivalent saviour of<br />

Artemisia’s work, we now have the technological<br />

means of ‘recreating’ her original painting while<br />

leaving the historic work, including Il Volteranno’s<br />

additions, intact, as US Florence-based conservator<br />

Elizabeth Wicks explains below.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 51

PLANS AND PULLEYS<br />

Elizabeth Wicks, who heads the project’s state-ofthe<br />

art team comprising expert technicians and<br />

restoration scientists, under the supervision of<br />

Casa Buonarroti Director Alessandro Cecchi and<br />

Jennifer Celani, official for the Archaeological<br />

Superintendence for the Fine Arts and Landscape<br />

for the metropolitan city of Florence, shares<br />

questions and insight about Artemisia’s veil, as<br />

the project enters phase 1.<br />

“Artemisia’s nude allegorical figure was covered<br />

up by Baldassare Franceschini, the artist known<br />

as ‘Il Volterrano’. With all due respect, to this<br />

famous Baroque painter, some of the veil work<br />

and drapery is surprisingly slapdash. This begs<br />

the question: Was this sloppiness due to a hasty<br />

commission, a deliberate affront to Artemisia’s<br />

painting, or was Il Volterrano uncomfortable about<br />

being tasked to cover the nude and, therefore,<br />

simply did not put his heart into it?<br />

From the outset, an important aspect of this<br />

project has been to create a virtual image of<br />

Artemisia’s original work, on the premise that<br />

the over-painting will not be removed,” Wicks<br />

explains. “The first reason is that Il Volteranno’s<br />

repaints are considered historic and part of the<br />

painting’s setting and life story. Secondly, there<br />

is only a 70-year difference between Artemisia’s<br />

painting and the ‘censoring’ draperies and veil.<br />

It’s a thick layer of paint, with impasto. It may turn<br />

out that the two artists’ layers are very strongly<br />

bonded, and, if that is the case, we absolutely<br />

cannot put the painting at risk.<br />

Beyond the veils, as mentioned in the<br />

description of the painting by contemporary<br />

biographer Filippo Baldinucci, and shown in<br />

a sketch by Michelangelo the Younger of his<br />

original idea for The Inclination in the Casa<br />

Buonarroti archives – he drew the iconographic<br />

plan of the entire Buonarroti Gallery ceiling –<br />

Artemisia’s allegorical figure originally had two<br />

pulleys at her feet. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to<br />

find those now-invisible pulleys, hiding under the<br />

clouds! Again, it is all hypothetical at this point.<br />

As the team makes discoveries and explores<br />

the Inclination’s needs from a philosophical and<br />

technical standpoint, we’ll gain the knowledge to<br />

make informed decisions. For now, it’s early days.<br />

I am still removing the paper and canvas layers<br />

glued to the back of the stretcher, and once that<br />

process is finished, we will be able to continue<br />

with diagnostics and begin conservation work on<br />

the front of the painting.<br />

Through working photographs, diagnostic<br />

imaging and analysis, we will be able to<br />

determine the exact technique Artemisia used,<br />

correctly map the work’s condition, and monitor<br />

our treatment plan for the painting. Due to the<br />

historic nature of the repaints, it is not possible<br />

to remove them from the surface, but the scope<br />

of our diagnostics will facilitate the creation of a<br />

virtual image of the original that lies beneath the<br />

surface of the painting, as we see it today,” Wicks<br />

explains. “Next week, we start our virtual journey<br />

‘beneath the veil’ under diffuse and raking light<br />

sources, followed by UV and infrared research.<br />

Hypercolormetric Multispectral Imaging and<br />

examination by digital microscope will then help<br />

us learn as much as possible about the condition<br />

of the original painting technique and the later<br />

repaints. X-ray and high-resolution reflectography<br />

and other analytical techniques will follow.” RC<br />

52 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Right: Artemisia Gentileschi’s<br />

Allegory of Inclination under<br />

raking light<br />

(Image: Ottaviano Caruso).<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 53

54 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

There’s no place like ‘home’<br />

Michelangelo’s house is Artemisia’s abode<br />

The modest via Ghibellina palazzo was one<br />

Artemisia herself frequented during her stint<br />

as a court painter in Florence, hobnobbing<br />

with Michelangelo the Younger – one of her most<br />

dedicated patrons and namesake of her daughter<br />

Agnola, born in 1614, who, unfortunately, died<br />

before she had time to be baptised.<br />

At Casa Buonarroti, Artemisia socialised with<br />

and befriended renowned members of the<br />

Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, Europe’s first<br />

drawing academy, of which Artemisia became a<br />

member in 1616. Her fellow members included<br />

Galileo, with whom the artist corresponded,<br />

even after his exile. The compass held aloft by<br />

the Inclination’s allegorical figure is thought<br />

to be a nod to the renowned scientist and his<br />

controversial theories.<br />

With her intelligence, exceptional selfpromotion<br />

skills, and the Grand Duke’s favour<br />

– Cosimo II had commissioned several works<br />

by the artist prior to the Buonarroti picture –<br />

Artemisia was at home in Florence’s cultural<br />

scene. “The seven years she spent in Florence<br />

marked a period of transformation for Artemisia,”<br />

writes Letizia Treves in the catalogue of<br />

Artemisia, the show she curated at London’s<br />

National Gallery in 2020. “She learnt to read and<br />

write, forged enduring friendships, met influential<br />

figures at the Medici court and moved in cultured<br />

intellectual circles. The artistic practices she had<br />

learnt from her father Orazio stayed with her, but<br />

her art took a new direction. Fully conscious of<br />

the singularity of her position as a gifted female<br />

painter, she frequently used her own image in her<br />

work and, as a member of the artists’ academy,<br />

was abreast of developments in contemporary<br />

art.”<br />

Artemisia had the opportunity to enter into<br />

dialogue with up-and-coming artists of her day,<br />

through her work on the Allegory of Inclination,<br />

one of a series of fifteen canvases, created by<br />

emergent Tuscan painters, to tribute the values<br />

of Michelangelo the Great. When the younger<br />

Buonarroti commissioned a five-month pregnant<br />

Artemisia Gentileschi to paint her piece for<br />

the piano nobile, or ‘first floor (fit for nobility)’,<br />

the artist’s fee was three times that of her male<br />

counterparts, and she is said to have been given<br />

more ‘iconographic freedom’ than the other artists<br />

involved, which include dall’Empoli, Passignano,<br />

Matteo Rosselli and Francesco Furini. On the<br />

ceiling, across from Artemisia’s canvas is a work<br />

by Francesco Bianco Buonavita – also painted in<br />

1616 – which depicts the attribute of Ingenio –<br />

the genius or intelligence one needs to produce<br />

art. This value is inclination’s inseparable twin –<br />

the drive to produce art must be accompanied by<br />

exceptional skill.<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 55

56 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

Previous pages: Views of the Casa Buonarroti<br />

Gallery Ceiling, (Image: Olga Makarova).<br />

Left: Saint Michael Archangel, Michelangelo<br />

Cinganelli, 1922, Casa Buonarroti Museum Chapel.<br />

Inset, below: Giuliano Finelli, Bust of Michelangelo<br />

the Younger, 1630, Casa Buonarroti Museum.<br />

The Gallery ceiling was, of course, merely a<br />

small part of a much larger project, conceived<br />

by Michelangelo the Younger, who shared<br />

his great uncle’s obsession with building an<br />

“honourable” home in Florence from the<br />

five buildings the artist had purchased in<br />

1508, the year he began work on the Sistine<br />

Chapel. [The museum’s street address is<br />

now number 70]. Buonarroti the Younger<br />

– a poet, playwright and academician<br />

– who incidentally was a great patron of<br />

female creativity (his support of composer<br />

Francesca Caccini is a case in point) –<br />

restored the complex with a home-museum<br />

in mind, and spent over three decades<br />

(1612 to 1643) working in his studiolo,<br />

a wooden booth-like structure, that<br />

could be described as a ‘walk-in<br />

desk’.<br />

In this miniature fortress<br />

of privacy, placed in what<br />

is now the seventeenthcentury<br />

wing, he worked<br />

to devise and execute<br />

a plan, in painstaking<br />

detail. Hence, this wing<br />

of the museum is entirely<br />

to his credit and, beyond<br />

the Gallery, it includes the<br />

Chamber of Day and Night, the<br />

jewel-box Chapel of Archangel<br />

Michael – the palace patron<br />

saint for obvious reasons – and the<br />

Studio, whose ceiling fresco tributes<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 57

Above: Model of the facade of the San Lorenzo Church<br />

Right, top: Battle of the Centaurs, Michelangelo Buonarroti<br />

(1490-92) Casa Buonarroti Museum.<br />

Right: Detail, Battle of the Centaurs, Michelangelo<br />

Buonarroti.<br />

‘the greats’ of all fields of knowledge. Even Galileo<br />

is featured among his scientist forefathers – a<br />

brave decision by Michelangelo the Younger, in a<br />

climate that would soon give rise to the scientist’s<br />

condemnation as a heretic for his heliocentric view<br />

of the Cosmos. (Galileo was sentenced to life in<br />

prison, later commuted to house arrest which he<br />

served in Arcetri, just south of Florence).<br />

58 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

For the duration of the Artemsia UpClose<br />

project, a life-size photograph of the artwork has<br />

taken its place inside the ceiling’s monumental<br />

frame, to avoid a gaping hole and assure the<br />

visitor Artemisia’s painting – under restoration<br />

in the adjacent Model Room, will return to her<br />

usual ‘height’ once Florence and the world has<br />

had a chance to see her up close. As a sidebar,<br />

the ‘Model’ in whose shadow the Inclination’s<br />

restoration is underway, is the architectural<br />

model of San Lorenzo Church that Michelangelo<br />

designed in circa 1518, by request of the Medici<br />

pope, Leo X, the second son of Lorenzo the<br />

Magnificent. Michelangelo had lived with the<br />

future Pope Leo X – then known as Giovanni –<br />

for part of his youth, after being discovered by<br />

Il Magnifico in the San Marco sculpture-garden<br />

workshop, and invited to live in the Medici<br />

palace and be educated together with the<br />

Medici children.<br />

When Artemsia’s guests move from the<br />

Model Room, and walk towards the Gallery,<br />

they will cross the museum’s Marble Room,<br />

newly restored by Friends of Florence, and<br />

host to Michelangelo’s Madonna della<br />

Scala (c. 1491) and Battle of the Centaurs<br />

(c. 1492). There is a figure among the latter<br />

relief’s mass of wrestling bodies that<br />

Artemisia used as a source of inspiration<br />

for the positioning of her own allegorical<br />

figure. Look for the leaning figure on the<br />

left-hand side who is holding a cube-like<br />

stone which he is preparing to launch into<br />

the chaos – he is Michelangelo’s man who<br />

inspired our woman. RC<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 59

Left: Biffoli-Sostegni<br />

Manuscript. Library of<br />

the Royal Conservatories<br />

of Brussels, Belgium<br />

Manuscript B-Bc 27766<br />

(page 23v).<br />

Overleaf: Musica Secreta<br />

CD covers.<br />

60 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong>

The ‘archive angel’ and new<br />

music from the Renaissance<br />

Musica Secreta’s Laurie Stras on women’s voices<br />

By Margie MacKinnon<br />

I“<br />

I’ve made it my musicological life goal to restore<br />

the female voice to its central role in the sound<br />

of the Renaissance city.” These are the words of<br />

Laurie Stras, director of Musica Secreta, a British<br />

vocal ensemble founded in 1991 to explore,<br />

perform and record music written by and for<br />

women in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.<br />

Stras is making the point that traditional musical<br />

history focuses on compositions that would have<br />

been performed (by men) at great Papal and ducal<br />

chapels – accessible to only a small number of<br />

‘worthy’ individuals. The music that would have<br />

been familiar to ordinary citizens, on the other<br />

hand, was “the sound of female voices, going up<br />

to God, and maintaining the spiritual health of the<br />

city”. People could walk into a convent at almost<br />

any hour of the day and hear women’s voices.<br />

“The sisters would have spent at least eight hours<br />

singing,” notes Stras, “and would never have got<br />

much sleep!”<br />

<strong>Autumn</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2022</strong> • Restoration Conversations 61

Over the course of 30 years, Musica Secreta<br />

have recorded ten CDs, four of which are of<br />

music exclusively by historic women composers.<br />

Their most recent CD, Mother Sister Daughter,<br />