Module 4 - Introduction to Performance Audit_4C

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>4C</strong>. Performing a <strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong> Engagement (20%)<br />

<strong>4C</strong>. Learning Outcomes<br />

On completion of this <strong>Module</strong>, students will be better able <strong>to</strong>:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Explain the requirements for gathering information for a performance audit.<br />

Propose measures for evaluating economy, effectiveness, and efficiency.<br />

Describe the relative reliability of different sources of information that may be used.<br />

Identify potential sources of error in gathering information.<br />

Select appropriate methods for evaluating information.<br />

Generate valid conclusions and recommendations.<br />

<strong>4C</strong>.1 <strong>Audit</strong>ing Economy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency<br />

The greatest differences in performance audits when compared with other kinds of internal<br />

audit engagements occur in the planning and preparation stages. The processes for<br />

performing, documenting, reporting, and completing follow-up are somewhat similar. The<br />

focus of all stages of a performance engagement is <strong>to</strong> measure and evaluate performance<br />

according <strong>to</strong> the audit objectives, questions, scope, criteria, and methodology, and provide<br />

an assessment of efficiency, economy, and effectiveness.<br />

The IPPF covers standards relevant for performing all kinds of engagements, as identified in<br />

section 4A.2 above. Information gathering as it relates <strong>to</strong> planning and any pre-study is<br />

described in section 4B.5 but this process continues throughout the engagement.<br />

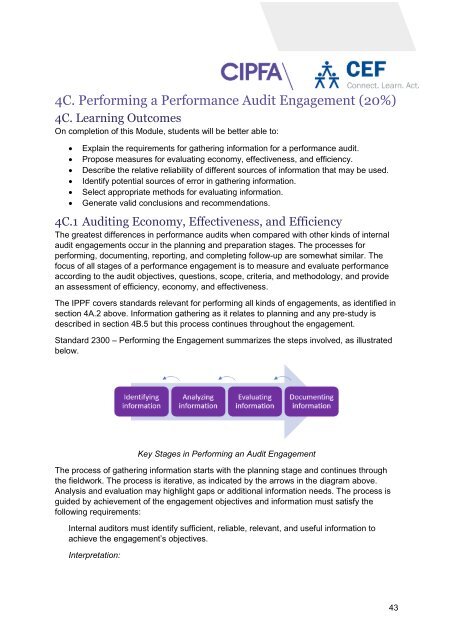

Standard 2300 – Performing the Engagement summarizes the steps involved, as illustrated<br />

below.<br />

Key Stages in Performing an <strong>Audit</strong> Engagement<br />

The process of gathering information starts with the planning stage and continues through<br />

the fieldwork. The process is iterative, as indicated by the arrows in the diagram above.<br />

Analysis and evaluation may highlight gaps or additional information needs. The process is<br />

guided by achievement of the engagement objectives and information must satisfy the<br />

following requirements:<br />

Internal audi<strong>to</strong>rs must identify sufficient, reliable, relevant, and useful information <strong>to</strong><br />

achieve the engagement’s objectives.<br />

Interpretation:<br />

43

Sufficient information is factual, adequate, and convincing so that a prudent,<br />

informed person would reach the same conclusions as the audi<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

Reliable information is the best attainable information through the use of<br />

appropriate engagement techniques.<br />

Relevant information supports engagement observations and recommendations<br />

and is consistent with the objectives for the engagement.<br />

Useful information helps the organization meet its goals. 68<br />

Useful<br />

Sufficient<br />

Reliable<br />

Relevant<br />

Requirements for Identifying Information<br />

ISSAI 3000 provides direction on establishing sufficiency of evidence:<br />

106) The audi<strong>to</strong>r shall obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence in order <strong>to</strong> establish<br />

audit findings, reach conclusions in response <strong>to</strong> the audit objective(s) and audit<br />

questions and issue recommendations when relevant and allowed by the SAI’s<br />

mandate. 69<br />

Sufficiency refers <strong>to</strong> the quantity of evidence, being enough <strong>to</strong> achieve the objectives <strong>to</strong><br />

satisfy a “reasonable” person (compared with a “prudent informed person” in The IIA<br />

Standards). Arriving at sufficient evidence requires a professional judgment based on<br />

consideration of audit risk, materiality, and the significance of the finding.<br />

The other three dimensions – relevance, reliability, and usefulness – concern the<br />

appropriateness of the evidence. This in turn relates <strong>to</strong> the importance of the evidence <strong>to</strong> the<br />

audit <strong>to</strong>pic, as well as its accuracy, consistency, and verifiability. There is a natural hierarchy<br />

of evidence with respect <strong>to</strong> its relative reliability which is illustrated below, from greatest <strong>to</strong><br />

least.<br />

68<br />

Standard 2310 – Identifying Information, The International Professional Practices<br />

Framework, The IIA, 2016.<br />

69<br />

ISSAI 3000 <strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong> Standard, INTOSAI, 2019.<br />

44

Direct<br />

•Evidence gathered directly by the audi<strong>to</strong>r through<br />

observation.<br />

Documentary<br />

•Original documentation in preference <strong>to</strong> copies.<br />

Testimonial<br />

•Multiple interviews from knowledgeable, credible,<br />

unbiased persons, under relaed conidi<strong>to</strong>ns, corroborated<br />

in writing, in preference <strong>to</strong> individual testimonies or those<br />

that are oral only.<br />

Analytical<br />

•Where the audi<strong>to</strong>r has applied analytical techniques <strong>to</strong><br />

process availabel information and extract key evidence,<br />

in preference <strong>to</strong> analysis performed by another party.<br />

Relative Reliability of Evidence<br />

Information gathering techniques can draw evidence from the audited entity as well as from<br />

other sources (“such as clients, experts, civil society organisations, contrac<strong>to</strong>rs, professional<br />

organisations, research organisations or other government entities”). 70 Common sources<br />

and approaches are listed below.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Direct:<br />

o Direct observation.<br />

o Physical inspection.<br />

o Testing.<br />

Documentary:<br />

o Original or copies, e.g., plans, contracts, policies, case studies, and reports.<br />

o Electronic as well as paper based.<br />

o Text-based, graphical, pho<strong>to</strong>graphic, audio, and video.<br />

Testimonial:<br />

o Direct (e.g., interviews and conversations conducted in-person, via telephone,<br />

or teleconferencing), conducted individually or in groups (e.g., focus groups,<br />

panels).<br />

o Indirect (via written statements, surveys, recordings, etc.).<br />

Analytical:<br />

o Where the audi<strong>to</strong>r performs analytical techniques <strong>to</strong> process, aggregate,<br />

summarize, extrapolate, and otherwise <strong>to</strong> interpret information and identify<br />

patterns, trends, and salient data points. Techniques for making sense of<br />

information gathered, recognizing root causes, and identifying outcomes and<br />

impacts include walk throughs, process mapping, five whys, charting,<br />

regression, and fishtail diagrams.<br />

o Quantitative analysis may be statistical or descriptive. Qualitative analysis<br />

includes thematic, chronological, and <strong>to</strong>pical approaches.<br />

70<br />

<strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong> ISSAI Implementation Handbook, IDI, 2021.<br />

45

Case studies are listed above as a potential documentary source but may be used as a<br />

research method conducted by the audi<strong>to</strong>r in which a detailed analysis is made of a<br />

particular aspect of the subject matter as a way of discovering useful learning points about<br />

the subject matter as whole.<br />

Measuring Economy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency<br />

The audi<strong>to</strong>r must select appropriate measures <strong>to</strong> support conclusions regarding the<br />

economy, effectiveness, and efficiency of the subject matter. Measures may be qualitative<br />

and quantitative as well as financial and nonfinancial, and should consider:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Inputs (resources applied).<br />

o Efficiency (i.e., the degree <strong>to</strong> which use of resource is minimized) can be<br />

measured using input-<strong>to</strong>-output ratios in terms of costs and volumes or by<br />

input-<strong>to</strong>-input ratios of different categories of inputs (e.g., staffing costs as a<br />

percentage of <strong>to</strong>tal costs).<br />

o Economy (i.e., degree <strong>to</strong> which resource costs are minimized), including<br />

trends over time and variations between locations, teams, and individuals.<br />

o Cost of quality, including quality assurance processes and the impact of<br />

failures and wastage.<br />

Output – work produced or services delivered.<br />

o Output quantity.<br />

o Output quality.<br />

o Output timeliness.<br />

o Output costs.<br />

Outcomes – results achieved.<br />

o Effectiveness of outputs in achieving the intended purpose. 71<br />

Outcomes relate <strong>to</strong> the effects beyond the entity on people such as service users and civil<br />

society as well as broader dimensions like the environment, law and order, the economy,<br />

national security, and international relations. These long-term outcomes may be described<br />

as impacts. Effectiveness measures the value added (or benefits) created by the subject<br />

matter. To measure this the audi<strong>to</strong>r should consider fac<strong>to</strong>rs such as:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Cus<strong>to</strong>mer satisfaction.<br />

Coverage.<br />

Financial results.<br />

Financial conditions.<br />

Readiness.<br />

In each case, the audi<strong>to</strong>r will need <strong>to</strong> determine a suitable unit of measure or proxy and a<br />

means of gathering evidence.<br />

In their analysis and evaluation, audi<strong>to</strong>rs are likely <strong>to</strong> need <strong>to</strong> apply a range of operational,<br />

financial, and statistical techniques, including net present value (NPV), internal rate of return<br />

(IRR), linear programming, regression, and appropriate financial margins and ratios.<br />

Common project appraisal models covered in this <strong>Module</strong> are described below.<br />

71<br />

See Rauum and Morgan, <strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong>ing: A Measurement Approach, The Internal<br />

<strong>Audit</strong> Research Foundation, 2009.<br />

46

Payback<br />

The concept of payback is straightforward. The method answers the question: how long will<br />

it take for the net cash inflows (i.e., any additional revenues and cost savings) <strong>to</strong> be equal <strong>to</strong><br />

the investment needed at the beginning? The payback period can be calculated on the basis<br />

of projected or actual results. Once calculated it can be compared with other investment<br />

options <strong>to</strong> help select the projects <strong>to</strong> be funded. For projects already completed, the result<br />

can be compared with planned payback or benchmarks.<br />

For example, the following detail relates <strong>to</strong> a project.<br />

Year<br />

Additional cash<br />

outflows<br />

(000,000 LEK)<br />

Net cash inflows (from additional<br />

revenue and/or saved costs)<br />

(000,000 LEK)<br />

0 158 (setup costs)<br />

1 18<br />

2 41<br />

3 65<br />

4 85<br />

5 85<br />

Year 0 is the theoretical point at which investment is made and the project begins. An<br />

assumption is usually made that cashflows accrue evenly through the year.<br />

The first step is <strong>to</strong> add a cumulative column for net cash inflows.<br />

Year<br />

Additional cash<br />

outflows<br />

(000,000 LEK)<br />

Net cash inflows (from additional<br />

revenue and/or saved costs)<br />

(000,000 LEK)<br />

Cumulative net<br />

cash inflows<br />

(000,000 LEK)<br />

0 158 (setup costs)<br />

1 18 18<br />

2 41 59<br />

3 65 124<br />

4 85 209<br />

5 85 294<br />

You can see in this case that at some point during year 4 the cumulative <strong>to</strong>tal passes the<br />

initial cost of set up 158. The payback period is somewhere between 3 and 4 years. Year 4<br />

begins with a cumulative <strong>to</strong>tal of 124. A further 34,000,000 LEK is needed <strong>to</strong> reach<br />

158,000,000 LEK. If we assume an even rate of cashflows, it will take 34/85 = 0.4 of a year<br />

or 4.8 months.<br />

Therefore, Payback period is 3.4 years or 3 years and 4.8 months.<br />

The method is simple, easy <strong>to</strong> understand and easy <strong>to</strong> calculate. However, it ignores the fact<br />

that future cashflows are harder <strong>to</strong> estimate accurately. It also ignores the time value of<br />

money (i.e., that money that will be received in the future is worth less than money that will<br />

be received sooner.)<br />

Discounted Cashflow (DCF) and Net Present Value (NPV)<br />

47

To account for the time value of money, project appraisal methods can use discounted<br />

cashflows (DCF). Capital has an assumed cost. It must be borrowed or used from reserves<br />

in which the cost is the opportunity cost of not doing something else with it (like investing it).<br />

The further ahead a cashflow occurs (or is predicted <strong>to</strong> occur), the lower its relative value.<br />

The cost of capital has a cumulative effect.<br />

For example, suppose the assumed cost of capital is 10%. We can calculate discounted<br />

cashflow fac<strong>to</strong>rs. The formula is:<br />

Discount fac<strong>to</strong>r = 1/(1 + discount rate) years<br />

In this case, the discount rate is 10% or 0.1. Discount fac<strong>to</strong>rs are as follows:<br />

Year<br />

Discount<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>r<br />

0 1.000<br />

1 0.909<br />

2 0.826<br />

3 0.751<br />

4 0.683<br />

5 0.621<br />

(Note: These discount fac<strong>to</strong>rs are available as tables online or in published form, and in an<br />

exam you would not be expected <strong>to</strong> calculate them.)<br />

We use these fac<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> discount future cashflows <strong>to</strong> the present value. 1 LEK <strong>to</strong>day is worth<br />

1 Lek. 1 LEK in a year’s time has the same value as 0.909 LEK <strong>to</strong>day. I could invest 0.909<br />

LEK <strong>to</strong>day for a year and at the end I will have 1 LEK.<br />

We can use these fac<strong>to</strong>rs with the information given in the Payback example.<br />

Year<br />

Discount<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Net cash<br />

inflow/(outflow)<br />

Discounted<br />

cashflow<br />

Cumulative discounted<br />

cashflow<br />

0 1.000 (158) (158) (158)<br />

1 0.909 18 16 (142)<br />

2 0.826 41 34 (108)<br />

3 0.751 65 49 (59)<br />

4 0.683 85 58 (1)<br />

5 0.621 85 53 52<br />

In this case we can see the project does not have a positive cumulative discounted cashflow<br />

until just after the end of year four. Our Payback period on this basis is just over four years. It<br />

is longer than our previous calculation because we have discounted the cashflows, the<br />

further they are in the future, the greater the amount of discount. 85,000,000 LEK received in<br />

five years’ time has the same value as 53,000,000 LEK received <strong>to</strong>day.<br />

Financial ratios<br />

48

Financial ratios may be used in performance auditing <strong>to</strong> analyse project information. In<br />

particular, the efficiency and profitability ratios studied in <strong>Module</strong> 3 may be useful for this<br />

purpose.<br />

Efficiency and profitability<br />

Operating Margin Surplus (or deficit) ÷ Revenue x 100 %<br />

Expense Margins Individual Expense ÷ Revenue x 100 %<br />

Return on Assets Surplus (or deficit) ÷ Assets x 100 %<br />

In these calculations, the revenues, expenses and assets relate solely <strong>to</strong> the project,<br />

programme or entity under review.<br />

As noted in sections 4A.2 and 4A.3, audi<strong>to</strong>rs must remain alert <strong>to</strong> the importance of audit<br />

risk and materiality at all stages of the engagement, while quality assurance arrangements,<br />

including supervision, are also essential throughout. <strong>Audit</strong> documentation is likewise<br />

completed at all stages and is described below in section <strong>4C</strong>.2.<br />

There is an important difference between information and evidence. Information becomes<br />

evidence when it is used in support of a condition. This requires the information <strong>to</strong> be<br />

analyzed and evaluated using acceptable logical and numerical techniques <strong>to</strong> ensure<br />

conclusions are valid.<br />

<strong>4C</strong>.1: Reflection<br />

Which, if any, is the most important dimension of performance: efficiency, economy, or<br />

effectiveness?<br />

Which is the hardest dimension <strong>to</strong> measure: efficiency, economy, or effectiveness?<br />

As the audi<strong>to</strong>r, how do you know when you have satisfied the requirement for sufficiency<br />

of information?<br />

<strong>4C</strong>.2 <strong>Audit</strong> Documentation<br />

Standard 2330 – Documenting Information describes the requirements for internal audi<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

<strong>to</strong> maintain records during an engagement. Documentation must be available <strong>to</strong> support the<br />

results and conclusions recorded in the report. Much of the standard focuses on access and<br />

retention.<br />

Internal audi<strong>to</strong>rs must document sufficient, reliable, relevant, and useful information <strong>to</strong><br />

support the engagement results and conclusions.<br />

2330.A1 The chief audit executive must control access <strong>to</strong> engagement records. The<br />

chief audit executive must obtain the approval of senior management and/or legal<br />

counsel prior <strong>to</strong> releasing such records <strong>to</strong> external parties, as appropriate.<br />

2330.A2 The chief audit executive must develop retention requirements for engagement<br />

records, regardless of the medium in which each record is s<strong>to</strong>red. These retention<br />

49

equirements must be consistent with the organization’s guidelines and any pertinent<br />

regula<strong>to</strong>ry or other requirements.<br />

2330.C1 The chief audit executive must develop policies governing the cus<strong>to</strong>dy and<br />

retention of consulting engagement records, as well as their release <strong>to</strong> internal and<br />

external parties. These policies must be consistent with the organization’s guidelines and<br />

any pertinent regula<strong>to</strong>ry or other requirements. 72<br />

The audi<strong>to</strong>r must determine what should be documented while avoiding the temptation <strong>to</strong><br />

include every piece of information gathered. Data should only be included if it is used as<br />

evidence <strong>to</strong> support conditions and recommendations.<br />

While evidence may include physical evidence (such as samples) and testimonials from<br />

individuals and groups, generally evidence is prepared in digital or paper-based format that<br />

are records derived from multiple sources. Documentation requirements also include records<br />

of analysis. The steps taken <strong>to</strong> establish the sufficiency, reliability, relevance, and usefulness<br />

of evidence should be clear from the documentation.<br />

Potential weaknesses in each major category of evidence are considered by Rauum and<br />

Morgan where the audi<strong>to</strong>r should take extra care, as shown below.<br />

Physical Evidence – be alert <strong>to</strong> evidence that:<br />

Is collected without a specific methodology and may not be representative (i.e., it may<br />

be an isolated case or an outlier).<br />

Is a pho<strong>to</strong>graph without a record of observation or memo <strong>to</strong> the record.<br />

Lacks a clear chain of cus<strong>to</strong>dy (e.g., police confiscated drugs).<br />

Lacks a test of inven<strong>to</strong>ry (i.e., may look at an oil tank and assume it is full of oil when<br />

actually it contains mostly water with a layer of oil on <strong>to</strong>p).<br />

Is not witnessed (i.e., comes from only one observer).<br />

Is collected by an unqualified observer.<br />

Is a “setup” (i.e., contrived <strong>to</strong> give a false or misleading impression).<br />

Documentary Evidence – be alert <strong>to</strong> evidence that is:<br />

Taken out of context (pulled from other documents).<br />

From a newspaper or magazine article (which may be biased by personal, political,<br />

religious, or other opinion).<br />

Other audi<strong>to</strong>rs’ work (i.e., relying on their work without checking).<br />

From a secondary, not a primary, source.<br />

Outdated.<br />

Unofficial.<br />

Refutable.<br />

Controversial.<br />

Incomplete.<br />

Unclear (unidentified acronyms, etc.).<br />

Inconsistent.<br />

72<br />

Standard 2330 – Documenting Information, The International Professional Practices<br />

Framework, The IIA, 2016.<br />

50

Testimonial Evidence – be alert <strong>to</strong> evidence that is:<br />

From a source whose knowledge about the <strong>to</strong>pic is in doubt.<br />

From a source whose credibility is questionable.<br />

From a source who is not impartial and/or has a vested interest.<br />

The only evidence used <strong>to</strong> support a point (for example, if we rely only on statements<br />

from one person – one worker in a group of workers).<br />

Uncorroborated.<br />

Used out of context.<br />

Inconsistent.<br />

Incomplete.<br />

A “snow job” (an attempt <strong>to</strong> flatter or persuade).<br />

Disguised as documentary evidence (examples: written comments or numbers written<br />

or typed on a blank piece of paper by an official during an interview).<br />

Improperly substituted for documentary evidence (e.g., relying on what an official <strong>to</strong>ld<br />

us the law says instead of obtaining the law or using testimony for the date of a<br />

contract was signed instead of using the contact).<br />

Analytical Evidence – be alert <strong>to</strong> evidence that:<br />

Uses inappropriate analysis.<br />

Lacks methodological rigor.<br />

Is based on erroneous or useless physical, documentary, and/or testimonial evidence.<br />

Is interpreted inappropriately.<br />

Depends on microcomputer work that does not used quality assurance/control<br />

procedures.<br />

Potential Weaknesses in Evidence 73<br />

The process of documenting evidence should be covered by quality assurance procedures.<br />

Care should always be taken <strong>to</strong> protect personal, confidential, and sensitive information.<br />

To help with the process of audit documentation, some teams use a template or matrix, like<br />

the one given below, <strong>to</strong> structure the results. Findings are conclusions based on the analysis<br />

of information, should be stated succinctly and precisely, and be supported by a clear<br />

expression of the criteria used, the condition identified, the causes of the condition, and the<br />

effects of the condition (the outcomes and impacts).<br />

<strong>Audit</strong> objective<br />

<strong>Audit</strong> question(s)<br />

Condition<br />

Criteria<br />

Finding Evidence,<br />

analysis<br />

Cause(s)<br />

Effect(s)<br />

Developed in the planning stages, linked <strong>to</strong> the scope<br />

Developed <strong>to</strong> help expand and investigate the objective<br />

Relevant discoveries during information gathering (a description of<br />

actual performance in terms of economy, effectiveness, and<br />

efficiency)<br />

Expected or desired conditions<br />

Supporting evidence for the condition<br />

Identification of root causes for the condition<br />

Identification of actual or likely outcomes and impacts of the<br />

condition<br />

73<br />

Rauum and Morgan, <strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong>ing: A Measurement Approach, The Internal <strong>Audit</strong><br />

Research Foundation, 2009.<br />

51

Sufficiency<br />

Good practices<br />

Conclusions<br />

Recommendations<br />

Confirmation or otherwise of the sufficiency of evidence <strong>to</strong> support<br />

the conclusions given as well as a description of any remaining<br />

work needed<br />

Examples of good practice or benchmarks that may inform<br />

recommendations for improvement<br />

Summary messages, opinions, and answers <strong>to</strong> audit questions<br />

Proposals <strong>to</strong> address deficiencies and make improvements<br />

<strong>Audit</strong> Findings Matrix 74<br />

Conclusions and recommendations may not be developed for every finding and are often<br />

based on multiple findings.<br />

<strong>4C</strong>.2: Reflection<br />

How do you decide what information needs <strong>to</strong> be documented <strong>to</strong> prevent excessive audit<br />

documentation?<br />

What kind of evidence can be the most problematic for an audi<strong>to</strong>r when determining<br />

reliability (direct, documentary, testimonial, or analytical)?<br />

What standard templates are used by your internal audit function <strong>to</strong> document results?<br />

What improvements could be made <strong>to</strong> those templates?<br />

74<br />

Adapted from <strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong> ISSAI Implementation Handbook, IDI, 2021. For more on<br />

audit design matrix and evidence collection planning, see for example European Court of<br />

Audi<strong>to</strong>rs “<strong>Performance</strong> <strong>Audit</strong> Manual,”<br />

52