Studies in Major Authors (ENGL 440), Fall 2006 Dr ... - View Site

Studies in Major Authors (ENGL 440), Fall 2006 Dr ... - View Site

Studies in Major Authors (ENGL 440), Fall 2006 Dr ... - View Site

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Dr</strong>. Aaron J Kleist, aka <strong>Dr</strong>. Vonk<br />

BEOWULF: THE HERO, THE MONSTERS, AND THE CULTURAL TEXT<br />

<strong>Studies</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Major</strong> <strong>Authors</strong> (<strong>ENGL</strong> <strong>440</strong>), <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

Email: aaron.kleist@biola.edu<br />

Extension: x 5581<br />

Office: SH 216<br />

Office<br />

Hours:<br />

T/Th 9.30am–12.30pm and 4.30–6.00pm;<br />

W 9.30–12.30 and 1.30–3pm<br />

BY EMAIL APPOINTMENT<br />

ITA † : Ms. Michael D<strong>in</strong>smoor Email: michael.k.d<strong>in</strong>smoor@bubbs.biola.edu<br />

†Illustrious Teach<strong>in</strong>g Assistant. Ita <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> means “thus” or “so”: when assistance <strong>in</strong> pedagogical skullduggery is required, therefore, ‘tis the Vonkian ITA who (<strong>in</strong> Jean-Luc’s term<strong>in</strong>ology) makes it so.<br />

Required Texts:<br />

Anonymous, Beowulf, trans. Seamus Heaney (Norton, 2001) [ISBN: 0393975800]<br />

Clark-Hall, J. R. and Herbert T. Meritt, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (U of Toronto P, 1984)<br />

[ISBN: 0802065481]<br />

Hasenfratz, Robert, and Thomas Jambeck, Read<strong>in</strong>g Old English: An Introduction (West Virg<strong>in</strong>ia<br />

University, 2005) [ISBN: 1933202017]<br />

Jack, George, ed., Beowulf: A Student Edition (Oxford, 1994) [ISBN: 0198710445]<br />

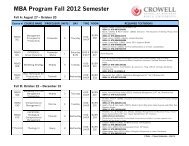

PROPOSED SCHEDULE (subject to change <strong>in</strong> the event of blizzards, locust plagues, or alien <strong>in</strong>vasion):<br />

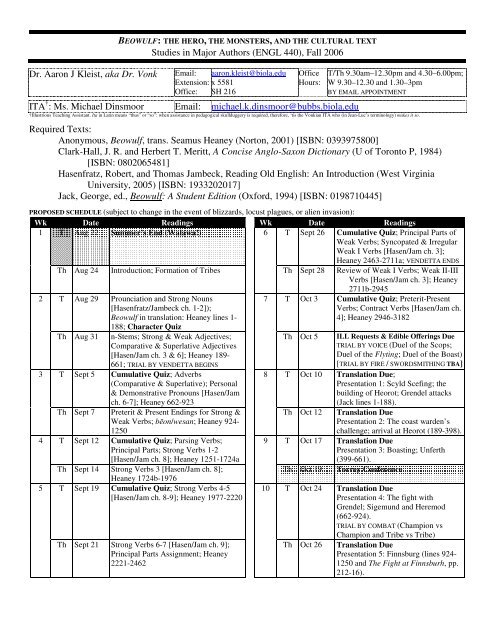

Wk Date Read<strong>in</strong>gs Wk Date Read<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

1 T Aug 22 Summer’s End (Walawa!) 6 T Sept 26 Cumulative Quiz; Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal Parts of<br />

Weak Verbs; Syncopated & Irregular<br />

Weak I Verbs [Hasen/Jam ch. 3];<br />

Heaney 2463-2711a; VENDETTA ENDS<br />

Th Aug 24 Introduction; Formation of Tribes<br />

Th Sept 28 Review of Weak I Verbs; Weak II-III<br />

Verbs [Hasen/Jam ch. 3]; Heaney<br />

2711b-2945<br />

2 T Aug 29 Prounciation and Strong Nouns<br />

7 T Oct 3 Cumulative Quiz; Preterit-Present<br />

[Hasenfratz/Jambeck ch. 1-2]);<br />

Verbs; Contract Verbs [Hasen/Jam ch.<br />

Beowulf <strong>in</strong> translation: Heaney l<strong>in</strong>es 1-<br />

188; Character Quiz<br />

4]; Heaney 2946-3182<br />

Th Aug 31 n-Stems; Strong & Weak Adjectives;<br />

Th Oct 5 ILL Requests & Edible Offer<strong>in</strong>gs Due<br />

Comparative & Superlative Adjectives<br />

TRIAL BY VOICE (Duel of the Scops;<br />

[Hasen/Jam ch. 3 & 6]; Heaney 189-<br />

Duel of the Flyt<strong>in</strong>g; Duel of the Boast)<br />

661; TRIAL BY VENDETTA BEGINS<br />

[TRIAL BY FIRE / SWORDSMITHING TBA]<br />

3 T Sept 5 Cumulative Quiz; Adverbs<br />

8 T Oct 10 Translation Due;<br />

(Comparative & Superlative); Personal<br />

Presentation 1: Scyld Scef<strong>in</strong>g; the<br />

& Demonstrative Pronouns [Hasen/Jam<br />

build<strong>in</strong>g of Heorot; Grendel attacks<br />

ch. 6-7]; Heaney 662-923<br />

(Jack l<strong>in</strong>es 1-188).<br />

Th Sept 7 Preterit & Present End<strong>in</strong>gs for Strong &<br />

Th Oct 12 Translation Due<br />

Weak Verbs; bēon/wesan; Heaney 924-<br />

Presentation 2: The coast warden’s<br />

1250<br />

challenge; arrival at Heorot (189-398).<br />

4 T Sept 12 Cumulative Quiz; Pars<strong>in</strong>g Verbs;<br />

9 T Oct 17 Translation Due<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal Parts; Strong Verbs 1-2<br />

Presentation 3: Boast<strong>in</strong>g; Unferth<br />

[Hasen/Jam ch. 8]; Heaney 1251-1724a<br />

(399-661).<br />

Th Sept 14 Strong Verbs 3 [Hasen/Jam ch. 8];<br />

Heaney 1724b-1976<br />

Th Oct 19 Torrey Conference<br />

5 T Sept 19 Cumulative Quiz; Strong Verbs 4-5 10 T Oct 24 Translation Due<br />

[Hasen/Jam ch. 8-9]; Heaney 1977-2220<br />

Presentation 4: The fight with<br />

Grendel; Sigemund and Heremod<br />

(662-924).<br />

TRIAL BY COMBAT (Champion vs<br />

Champion and Tribe vs Tribe)<br />

Th Sept 21 Strong Verbs 6-7 [Hasen/Jam ch. 9];<br />

Th Oct 26 Translation Due<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal Parts Assignment; Heaney<br />

Presentation 5: F<strong>in</strong>nsburg (l<strong>in</strong>es 924-<br />

2221-2462<br />

1250 and The Fight at F<strong>in</strong>nsburh, pp.<br />

212-16).

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

T Oct 31 Translation Due<br />

Presentation 6: Revenge for Grendel<br />

(1251-1491).<br />

Th Nov 2 Translation Due<br />

Presentation 7: The contest with<br />

Grendel’s mother; Hrothgar’s “Sermon”<br />

(1492-1724a).<br />

T Nov 7 Translation Due<br />

Presentation 8: The Sermon concludes;<br />

the journey home; [Mod]thryth[o]<br />

(1724b-1976).<br />

Th Nov 9 Research Paper Logical Outl<strong>in</strong>e Due<br />

Annotated Edition Due<br />

TRIAL BY WATER (Beowulf and Breca;<br />

Beowulf and the Mere-Monsters; Vik<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Longship Warfare)<br />

T Nov 14 Paleography Tutorial<br />

Presentation 9: Beowulf recounts his<br />

exploits; 50 years pass; the badly<br />

damaged folio (1977-2220).<br />

Th Nov 16 Translation Due<br />

Presentation 10: The dragon appears; an<br />

ill-advised raid on Frisia; some<br />

unpleasantness with the Scylf<strong>in</strong>gs;<br />

Herebeald and Haethcyn (2221-2462).<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 2<br />

T Nov 21 Translation Due<br />

Presentation 11: More Swedish<br />

trouble; the fight with the dragon;<br />

Wiglaf to the rescue (2463-2711a).<br />

Th Nov 23 Thanksgiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

T Nov 28 Translation Due<br />

Presentation 12: The hoard is opened;<br />

the hero is history; gloomy news for<br />

Geats (2711b-2945).<br />

Th Nov 30 Research Paper Due<br />

Conclusion (2946-3182)<br />

T Dec 5 Beowulf Film<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Th Dec 7<br />

17 TBA Student Film Screen<strong>in</strong>gs &<br />

Anglo-Saxon Feast!<br />

STRATEGIC GOALS: This course will seek to hone skills and qualities crucial to your work at Biola, to your<br />

professional lives hereafter, and to your development as cultured, thoughtful human be<strong>in</strong>gs. It aims among other<br />

th<strong>in</strong>gs to help you grow <strong>in</strong> your ability . . .<br />

EXPECTED COURSE OUTCOMES<br />

(What’s our goal? What do we want to learn?)<br />

• to th<strong>in</strong>k critically about a text (or, put another way:)<br />

• to read a text closely so as to identify subtle nuances of<br />

language and l<strong>in</strong>es of reason<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

• to relate <strong>in</strong>dividual passages to larger themes <strong>in</strong> the work as<br />

a whole;<br />

• to express your analysis through well-planned logical<br />

arguments supported by textual evidence;<br />

• to evaluate the strengths and weakness of your arguments;<br />

• to understand Old English texts <strong>in</strong> their orig<strong>in</strong>al language;<br />

• to ga<strong>in</strong> the mental agility, acumen, and cultural sensitivity<br />

that comes from secondary-language learn<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

• to be discipl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> your time management;<br />

• to contribute effectively to and work <strong>in</strong> harmony with a<br />

team;<br />

• to lead discussion <strong>in</strong> such a way that you engage students’<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ds, <strong>in</strong>volve them actively <strong>in</strong> the learn<strong>in</strong>g process, help<br />

them remember key aspects of your analysis, and make the<br />

experience enjoyable;<br />

METHODS FOR<br />

AUGMENTING ABILITY<br />

(How are we go<strong>in</strong>g to do it?)<br />

class discussion,<br />

formal & <strong>in</strong>formal<br />

presentations, and<br />

writ<strong>in</strong>g assignments<br />

rigorous study of<br />

grammar &<br />

vocabulary;<br />

translation<br />

small-group<br />

assignments &<br />

preparation for<br />

presentation<br />

METHODS FOR<br />

ASSESSING LEARNING<br />

(How will we know<br />

if we achieved our goal?)<br />

In-Class Contributions;<br />

Individual Presentation;<br />

Annotated Edition;<br />

Research Paper<br />

Quizzes; Translations<br />

Individual Presentation;<br />

Handout

• to situate (i.e., to view or understand) a work <strong>in</strong> its cultural<br />

context;<br />

• to understand and to appreciate Anglo-Saxon and Germanic<br />

ways of life;<br />

• to identify blatant or subtle tensions between divergent<br />

values (e.g., Christian and pagan) <strong>in</strong> a text;<br />

• to ga<strong>in</strong> deeper <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to human nature and the human<br />

condition through contrast<strong>in</strong>g (or complementary)<br />

narratorial perspectives;<br />

• to reconstruct and read a work from its orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

manuscript(s);<br />

• to edit a work for pr<strong>in</strong>t, judg<strong>in</strong>g when emendation is<br />

necessary;<br />

• to view a text not simply as a pr<strong>in</strong>ted work but as the<br />

product of paleographic study and textual edit<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

• to become familiar with the history of scholarship and the<br />

ongo<strong>in</strong>g scholarly dialogue on key textual issues;<br />

• to exam<strong>in</strong>e a text not <strong>in</strong> isolation but <strong>in</strong> light of said<br />

dialogue;<br />

• to contribute to the current scholarly dialogue;<br />

corporate study and<br />

discussion of cultural<br />

& historical<br />

background<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ation of<br />

facsimiles & digital<br />

manuscript images;<br />

edit<strong>in</strong>g workshop<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

research;<br />

articles for class<br />

• to develop your love of literature The Trials;<br />

Anglo-Saxon Feast<br />

In addition, the course will seek<br />

• to engage your m<strong>in</strong>ds and to <strong>in</strong>volve you actively <strong>in</strong> the learn<strong>in</strong>g process;<br />

• to provide you with appropriate ongo<strong>in</strong>g feedback about your performance;<br />

• to use your assessments of the course to improve my curricular approach and pedagogy;<br />

• to challenge you to set high expectations of yourself and to achieve them by God’s grace;<br />

• to encourage vivacious discussion and driven, self-motivated study through activities that<br />

bond the class together and make learn<strong>in</strong>g fun; and <strong>in</strong> consequence<br />

• to have a ball explor<strong>in</strong>g Beowulf.<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 3<br />

In-Class Contributions;<br />

Research Paper<br />

Translations;<br />

M<strong>in</strong>i-Editions;<br />

Annotated Edition;<br />

Research Paper<br />

Presentation Handout;<br />

Presentation;<br />

Annotated Edition;<br />

Research Paper<br />

Cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g self-assessment<br />

[5-10-15 years on, ask: Are you<br />

still read<strong>in</strong>g, and if so, what?<br />

Where are you us<strong>in</strong>g the skills<br />

learned <strong>in</strong> this discipl<strong>in</strong>e?]<br />

The extent to which you grow <strong>in</strong> these areas will be measured by a variety of methods, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g both written<br />

and oral assignments, formal and <strong>in</strong>formal presentations, and <strong>in</strong>dividual as well as group-based exercises. Your<br />

f<strong>in</strong>al grade will be comprised of the follow<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

Grade Distribution Grad<strong>in</strong>g Scale<br />

In-Class Contributions 20% A+ 97.5 – 100 C 75– 77.99<br />

Participation <strong>in</strong> the Trials 10% A 94 – 97.49 C- 72– 74.99<br />

Quizzes 10% A- 90 – 93.99 D+ 69– 71.99<br />

Translations & Editions 15% B+ 87 – 89.99 D 66– 68.99<br />

Individual Presentation 25% B 84 – 86.99 D- 64– 65.99<br />

Handout 10% B- 81 – 83.99 F 0– 63.99<br />

Presentation 15% C+ 78 – 80.99<br />

Bibliographic Beowulf Project 30%<br />

Annotated Edition 10%<br />

Logical Outl<strong>in</strong>e P/F<br />

Research Paper 20%

A BIT OF PERSPECTIVE ON OUR ENDEAVOR<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 4<br />

This course represents an <strong>in</strong>vestment on your part. It’s not simply a matter of money or of time (“You mean I’m<br />

spend<strong>in</strong>g half a year of my life do<strong>in</strong>g this?!”), though you are, of course, pursu<strong>in</strong>g a degree—a worthy goal that<br />

will pay dividends <strong>in</strong> the Life Hereafter (after Biola, that is). Rather, this course is an <strong>in</strong>vestment by you <strong>in</strong> your<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d, your character, your beliefs, your understand<strong>in</strong>g of the world. My job is to give you as many<br />

opportunities as possible to grow <strong>in</strong> such areas through corporate and <strong>in</strong>dividual exploration of the subject<br />

matter at hand: the textual, ideological, and cultural world of Beowulf.<br />

Hmmm—actually, that sentence bears unpack<strong>in</strong>g a bit. The growth I want to foster <strong>in</strong> you, first of all, is<br />

multifold: growth <strong>in</strong> your ability to th<strong>in</strong>k critically—that is, to trace a logical argument (whether on the page or<br />

on the screen) and understand the ramifications of its nuances; growth <strong>in</strong> your maturity of character, expressed<br />

through a commitment to and perseverance <strong>in</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>g your best effort to the K<strong>in</strong>gdom work at hand: your study;<br />

growth <strong>in</strong> your appreciation for what makes a work of language and of visual art great. I want you to leave this<br />

course with a keener ability and a sharpened appetite for evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the world around you. We are made <strong>in</strong> the<br />

image of a highly-skilled Creator. It is our privilege and duty as Christians—one of the prime reasons we were<br />

made—to recognize and be drawn to and to fill our lives with good craftsmanship. As the man says, if your eyes<br />

are good, your whole body will be full of light. This course, like all your other courses, God will<strong>in</strong>g, is about<br />

help<strong>in</strong>g your eyes to see well.<br />

Now, where were we? “Opportunities to grow through corporate and <strong>in</strong>dividual exploration.” Alright; the<br />

necessity for <strong>in</strong>dividual exploration seems clear enough—you’re not (one hopes) pay<strong>in</strong>g someone else to take<br />

classes for you, after all—but what’s the benefit of striv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a corporate context? Two reasons at least come to<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d: vocational, relational, and sensational. Vocational, first of all: whether it is your dest<strong>in</strong>y (search your<br />

feel<strong>in</strong>gs, Luke) to pursue a high-power career <strong>in</strong> the world of <strong>in</strong>ternational bus<strong>in</strong>ess, preside over congressional<br />

appropriations committees, serve on elder or school boards, or wrangle preschoolers with other patient<br />

pedagogues (teachers, to wit), few traits will serve you as well as the ability to work effectively <strong>in</strong> teams. Be<br />

warned: teams are usually made up of people. This means that your glory may be stolen, your genius o’ercast,<br />

your gentle and longsuffer<strong>in</strong>g nature put to the test by moody, ignorant, lazy team members who lack your<br />

virtuous traits (though clearly, such could never happen <strong>in</strong> our class). In practical terms, therefore, corporate<br />

endeavor is good preparation for the World. Second, there’s the relational aspect. We few, we happy few, will<br />

be bound together mysteriously <strong>in</strong> these months ahead as together we face the Sl<strong>in</strong>gs and Arrows of Outrageous<br />

Fortune (i.e., those nefarious tw<strong>in</strong>s, Too Much to Do and Too Little Time to Do It). If persevere we do,<br />

exhort<strong>in</strong>g each other on, then all these bless<strong>in</strong>gs shall be ours: camaraderie, unity, shared purpose, striv<strong>in</strong>g, and<br />

satisfaction <strong>in</strong> success. ‘Tis (as Hamlet says) a consummation most devoutly to be wished. And f<strong>in</strong>ally, there’s<br />

the sensational. I’ve never <strong>in</strong>corporated assass<strong>in</strong>ation-games, sword-smithy<strong>in</strong>g, and Vik<strong>in</strong>g longboat warfare<br />

<strong>in</strong>to an exploration of Beowulf before, and may never do the class this way aga<strong>in</strong>. For all the work <strong>in</strong>volved,<br />

however, with God’s help it has the potential to be enormously reward<strong>in</strong>g—at least if the enrolment roster is<br />

any <strong>in</strong>dication.<br />

So, that’s “growth” and “corporate exploration” talked about. We also might mention “the subject matter at<br />

hand: the textual, ideological, and cultural world of Beowulf.” Why would this one anonymous work, surviv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle, battered copy, have particular potential for produc<strong>in</strong>g the growth we seek? To put it crudely, why<br />

wouldn’t your time be better spent study<strong>in</strong>g the Bible and/or Bus<strong>in</strong>ess? Actually, I hope you’re do<strong>in</strong>g both those<br />

th<strong>in</strong>gs: earnestly seek<strong>in</strong>g the Lord through his Word and consciously equipp<strong>in</strong>g yourself for your vocational<br />

future. (The Guild of English Scholars, if you’re not already aware of it, can help you do the latter.) As human<br />

be<strong>in</strong>gs, however, and as people engaged <strong>in</strong> the discipl<strong>in</strong>e of literature <strong>in</strong> particular, we <strong>in</strong>nately recognize the<br />

importance of Story <strong>in</strong> our lives. Stories—the best stories, at any rate—captivate, convey philosophical depths,<br />

capture and illum<strong>in</strong>e aspects of the world deeply familiar to us but which we might not have recognized before.<br />

It’s no wonder, therefore, that Christ’s parables provide some of his most profound teach<strong>in</strong>gs, or that the<br />

attention of young and old is riveted by a sentence that beg<strong>in</strong>s “Once upon a time.” In an age of burgeon<strong>in</strong>g

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 5<br />

books, however, why should Beowulf be s<strong>in</strong>gled out as a masterpiece of this craft? It’s not an easy question to<br />

answer, but there are a few elements to which I’d po<strong>in</strong>t by way of response. First, it’s a gripp<strong>in</strong>g story. Even<br />

without the raw elements of the tale itself: the desolation wrought by the monstrous k<strong>in</strong> of Ca<strong>in</strong>, the vengeance<br />

wreaked by his unnatural mother, the fury of the dragon that <strong>in</strong>spired Tolkien’s Smaug. Even without the<br />

paradox of the protagonist: his past obscurity and his audacious boasts, his unearthly triumphs as warrior and<br />

his fatal flaws as k<strong>in</strong>g. Even without the glamour of battle and the allure of fabulous beasts—still you have a<br />

text that for over a millennium has tantalized readers with its enigmatic complexity. One is challenged, for<br />

example, by the s<strong>in</strong>gle manuscript <strong>in</strong> which Beowulf survives: charred by fire, with edges eroded and letters<br />

legible only through ultraviolet light, it conta<strong>in</strong>s passages whose <strong>in</strong>terpretation has been cause for violent<br />

debate. Even where read<strong>in</strong>gs are clear, one must wrestle with such vex<strong>in</strong>g questions as the text’s orig<strong>in</strong> and<br />

theology: a possibly-eighth-century Germanic tale copied likely <strong>in</strong> a tenth-century English monastery, Beowulf<br />

<strong>in</strong>terweaves Christian and pagan elements with such subtlety that some have seen it either as an elaborate<br />

allegory or a parasitic corruption of an earlier tradition. Above all, perhaps, there are the age-old questions of<br />

human existence which this ancient work addresses: What qualities should characterize the ideal man? For what<br />

goals should he strive? When does perseverance aga<strong>in</strong>st all odds turn from heroism <strong>in</strong>to folly? In the end,<br />

whether it be due to the rivet<strong>in</strong>g nature of its storytell<strong>in</strong>g, its perplex<strong>in</strong>g manuscript context, its ambiguous<br />

testimony to compet<strong>in</strong>g cultural values, or its ability to capture fundamental truths of the human experience <strong>in</strong><br />

arrest<strong>in</strong>gly-elegant language, the result is a work that more than any other written <strong>in</strong> England prior to Chaucer—<br />

a period compris<strong>in</strong>g, temporally speak<strong>in</strong>g, the first half of English literature—down through time has dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

the literary landscape. And that’s why we’re study<strong>in</strong>g it.<br />

One last feature of this sentence so burdensome of explanation: “as many opportunities as possible.” It’s not<br />

simply a Norton edition of this text which we’ll be read<strong>in</strong>g. We’ll be learn<strong>in</strong>g Old English to discover the work<br />

<strong>in</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al—see<strong>in</strong>g it, if you will, <strong>in</strong> color, not black-and-white. We’ll be analyz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> detail cutt<strong>in</strong>g-edge<br />

digital reproductions of the problematic manuscript, experienc<strong>in</strong>g first-hand the challenges that separate the<br />

modern reader from this unique work. We’ll be explor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> depth scholarly debates surround<strong>in</strong>g Beowulf, and<br />

craft<strong>in</strong>g careful analyses that engage the contemporary discourse. We’ll be go<strong>in</strong>g beyond the classroom to learn<br />

skills central to Anglo-Saxon life: rhetorical wordplay, poetic storytell<strong>in</strong>g, the forg<strong>in</strong>g and wield<strong>in</strong>g of swords,<br />

and so forth. We’ll be produc<strong>in</strong>g a three-m<strong>in</strong>ute film of Beowulf entirely <strong>in</strong> Old English. And we’ll be<br />

celebrat<strong>in</strong>g our achievements with some amaz<strong>in</strong>g Old English food.<br />

This is why I say that the course is an <strong>in</strong>vestment: you will determ<strong>in</strong>e, by how much you <strong>in</strong>vest, how great will<br />

be your returns. And how will I know (if she real-ly loves me? I say a prayer with ev-ar-ree heartbe—ahhh,<br />

make that) if you are miserly or bounteous <strong>in</strong> your <strong>in</strong>vestment, yea verily? Behold the follow<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

1. IN-CLASS CONTRIBUTIONS: I place great value on earnest, enthusiastic engagement of texts. Some of the<br />

greatest joy I’ll have <strong>in</strong> class, <strong>in</strong> fact, will be <strong>in</strong> hear<strong>in</strong>g your <strong>in</strong>sights and see<strong>in</strong>g your m<strong>in</strong>ds at work. One of our<br />

goals, as we’ve seen, is to <strong>in</strong>volve you actively <strong>in</strong> the learn<strong>in</strong>g process rather than simply deluge you with<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation; to that end, your comments and analysis will provide much of the meat of our textual repasts.<br />

Ne’er fear: it’s not as though you have to give stunn<strong>in</strong>gly brilliant observations on the first day. Critical analysis<br />

is like a muscle which one tra<strong>in</strong>s and that grows stronger with exercise. I will be watch<strong>in</strong>g, however, to see if<br />

you’re apply<strong>in</strong>g your grey cells to the material, and evaluat<strong>in</strong>g to what extent you enrich our dialogue with your<br />

conclusions.<br />

1.1. ATTENDANCE: The astute observer will note that a student’s <strong>in</strong>-class contributions are immeasurably<br />

assisted by said student actually com<strong>in</strong>g to class (though there are occasions one is tempted to th<strong>in</strong>k otherwise).<br />

Plan on be<strong>in</strong>g here. This is a three-hour course meet<strong>in</strong>g twice a week, so you have two skips, and <strong>in</strong> the chaos of<br />

the semester you may well use them. For every class you miss thereafter, it will cost you a third of a letter<br />

grade. The results are devastat<strong>in</strong>g; plan not to experience them. Similarly, I expect you to be prompt: enter<strong>in</strong>g<br />

class after I am seated will cost a third of a skip. On the other hand, if someth<strong>in</strong>g extraord<strong>in</strong>ary comes up, please<br />

let me know. I’ve needed to attend a funeral before, been smitten by the plague, or have found myself pursued<br />

by voracious hoards of half-crazed Visigoths. We can talk. Conversely, if you haven’t used your skips by the

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 6<br />

end of the semester, I shall notice: not a few who were teeter<strong>in</strong>g just short of a higher grade have found that<br />

their diligent attendance made the difference.<br />

1.2. PARTICIPATION IN THE TRIALS: The world of Beowulf is a fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g one, but distanced from us by culture<br />

as well as language. For the variety of activities seek<strong>in</strong>g to engage the former through blood-pump<strong>in</strong>g, hands-on<br />

ways, see [6.] THE TRIALS and particularly [6.1.5.] VENDETTA/TRIAL PARTICIPATION below.<br />

2. QUIZZES: In the first half of the semester, we’ll be work<strong>in</strong>g hard at language acquisition, gett<strong>in</strong>g you familiar<br />

with the heady language of England a thousand years and more ago. Beowulf is a text rich <strong>in</strong> nuance and<br />

multifarious shades of mean<strong>in</strong>g that can only be appreciated through exam<strong>in</strong>ation of the orig<strong>in</strong>al. Such study<br />

will lead us <strong>in</strong>exorably to . . .<br />

3. TRANSLATIONS & EDITIONS: the f<strong>in</strong>al part of the semester we’ll be putt<strong>in</strong>g your new-found skills to use,<br />

exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g major sections of the text <strong>in</strong> Old English. In addition, follow<strong>in</strong>g paleography and edit<strong>in</strong>g workshops,<br />

you’ll be asked to reconstruct one or more passages from facsimiles (photographs of manuscripts) or highquality<br />

digital manuscript images and then edit these passages as if for publication. I should warn you now: it<br />

won’t be an easy task. There is only one manuscript copy of Beowulf <strong>in</strong> existence, and it was heavily damaged<br />

by a fire <strong>in</strong> 1731, shriveled <strong>in</strong>to a contracted mass by the heat and judged by at least one Keeper of Manuscripts<br />

to be “perfectly useless to the [British] Museum <strong>in</strong> every sense of the word.” Up for the challenge?<br />

4. INDIVIDUAL PRESENTATION: <strong>Studies</strong> over the last decade have shown that few traits are as valued by<br />

employers as the ability to lead effectively and to communicate clearly your ideas. At one po<strong>in</strong>t dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

semester, therefore, you will take the assigned read<strong>in</strong>g and lead the class through it, us<strong>in</strong>g whatever means you<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k appropriate. Remember the four-fold goal above: to engage your classmates’ m<strong>in</strong>ds, to <strong>in</strong>volve them<br />

actively <strong>in</strong> the learn<strong>in</strong>g process, to help them remember key aspects of your corporate analysis, and to make the<br />

experience enjoyable. Take each of these objectives seriously, and your presentation should be the stronger as a<br />

result.<br />

Above all, I will be evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the extent to which you identify key issues and passages <strong>in</strong> the read<strong>in</strong>g, help us<br />

comprehend and wrestle with those issues, and <strong>in</strong>form our understand<strong>in</strong>g of the text through your own<br />

conclusions and those of other scholars. In addition to the presentation proper—your organization, professional<br />

demeanor, <strong>in</strong>sight, thoroughness, time management, sensitivity (and firmness) <strong>in</strong> foster<strong>in</strong>g and direct<strong>in</strong>g class<br />

discussion, and so forth—I will assess your written preparation for the presentation (your notes, for example,<br />

from articles related to relevant subjects) as well as your handout. You need reflect only on this syllabus to<br />

grasp the importance I place on such material.<br />

Remember: while I’m not emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g creativity for this project as much as for some of my other classes, you<br />

certa<strong>in</strong>ly don’t have to be dull about it. I’ve seen Beowulf retold as an episode <strong>in</strong> “Brothers Grimm’s Violent<br />

Tales for Children”; I’ve found myself <strong>in</strong> a wake—that is (ahem) a Sombre Funeral—for the misunderstood<br />

warrior; I’ve even seen the text’s <strong>in</strong>tricate family relationships and <strong>in</strong>ternec<strong>in</strong>e strife exam<strong>in</strong>ed through “Danish<br />

Dat<strong>in</strong>g (and Other Ways to Avoid Those Awkward Blood-Feuds).” Just be sure that whatever creativity you<br />

employ facilitates rather than distracts from our textual analysis.<br />

In plann<strong>in</strong>g your presentation, it might be helpful to consider these evaluations of your predecessors:<br />

Sample Words of Praise:<br />

• “From the time you began, we were left <strong>in</strong> no doubt but that you had material to cover and a plan to<br />

pursue. . . . The class knew what was expected of them and felt that you knew where you were go<strong>in</strong>g.”<br />

• “The speeches [<strong>in</strong> your skit] were appropriate, were delivered with feel<strong>in</strong>g, and did a good job of<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g passages from the text <strong>in</strong>to your dialogue. You dealt with important issues <strong>in</strong> the text,<br />

worked well as a team, divided responsibilities evenly, dressed <strong>in</strong> keep<strong>in</strong>g with the event, and had a<br />

helpful order of ceremony to guide the audience.”<br />

• “You outl<strong>in</strong>ed your plan of action, . . . gave helpful historical background, . . . and got people to th<strong>in</strong>k

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 7<br />

more closely about various aspects of the text, ask<strong>in</strong>g for their <strong>in</strong>terpretation of various passages.”<br />

• “Throughout the above, you did an excellent job of <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the class and foster<strong>in</strong>g discussion: you<br />

punctuated your talk with questions, you called people by name (or learned those names you didn’t<br />

know), and you assigned passages to various folk for them to read and to analyze.”<br />

• “The most important weakness of the presentation might have been your failure to <strong>in</strong>volve the class <strong>in</strong><br />

the learn<strong>in</strong>g process, save that you forced the groups to demonstrate what they learned <strong>in</strong> answer<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

various riddles before allow<strong>in</strong>g them to move to subsequent stages. At the end of the presentation,<br />

moreover, you asked the groups to further show what they learned by summariz<strong>in</strong>g their experience at<br />

the various stages.”<br />

• “All the above was characterized by a superb <strong>in</strong>terplay of <strong>in</strong>struction and discussion: you displayed a<br />

deft hand <strong>in</strong> encourag<strong>in</strong>g even the shy to contribute, prais<strong>in</strong>g answers when given while not shy<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

re-direct<strong>in</strong>g misguided responses. You got people to th<strong>in</strong>k about the issues at hand without los<strong>in</strong>g<br />

control of the discussion, and summed it all up with humor.”<br />

Sample Words of Counsel:<br />

• “While the presentation conv<strong>in</strong>ced me that you understood the material, I’m not sure to what extent it<br />

helped the rest of the class understand the material.”<br />

• “Your creativity was both your strength and your downfall: for some scenes, while you created<br />

fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g characters, you left the audience wonder<strong>in</strong>g what the po<strong>in</strong>t of the episode was. What<br />

precisely did you want us to learn from the skit? The presentation also lacked unity: you presented us<br />

with a series of seem<strong>in</strong>gly-unrelated episodes which left us not a little dizzy. . . . Your overarch<strong>in</strong>g goal<br />

should be to help us to identify, to understand, and to remember what is important <strong>in</strong> the section at<br />

hand.”<br />

• “You might th<strong>in</strong>k a bit more about how you could help the class remember the key po<strong>in</strong>ts of your<br />

presentation: what do you want them to take away with them? A handout might be helpful <strong>in</strong> this regard,<br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g that you make use of it <strong>in</strong> class and don’t expect your fellows to just go home and read it on<br />

their own.”<br />

• “Emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g your ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts and mak<strong>in</strong>g clear transitions from one topic to another may have helped<br />

the class follow your arguments.”<br />

• “Consider how to work your audience <strong>in</strong>to the learn<strong>in</strong>g process: rather than simply giv<strong>in</strong>g them your<br />

conclusions, how can you get them to come to those conclusions (or other <strong>in</strong>sightful ones) themselves?”<br />

• “Ask<strong>in</strong>g after each po<strong>in</strong>t ‘Does anyone have any questions?’ is not, as you experienced, the best way to<br />

elicit participation save from self-motivated extroverts. How do you get the quiet people <strong>in</strong>volved? Call<br />

people by name, if noth<strong>in</strong>g else. Granted, you did ask specific questions at times, but you were all too<br />

ready to fill the silence with your own commentary. At some po<strong>in</strong>t, you’ve got to talk less and get them<br />

to talk more. Creatively <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g people is key to gett<strong>in</strong>g them to <strong>in</strong>ternalize <strong>in</strong>formation.”<br />

• “You had a considerable amount of material to cover, ran over time, and thus were not able to spend as<br />

much time <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g less-talkative members of the audience.”<br />

• “Rather than lead<strong>in</strong>g us firmly through a clearly-def<strong>in</strong>ed set of po<strong>in</strong>ts, it seemed as though you were<br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g your way spontaneously through a sea of assorted facts, and the class was left a bit at sea as a<br />

result. S<strong>in</strong>ce you were pressed for time, it might have been better for you to concentrate our attention on<br />

fewer po<strong>in</strong>ts which you then explored <strong>in</strong> more detail, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the class more <strong>in</strong> the analysis of those<br />

po<strong>in</strong>ts and ‘lectur<strong>in</strong>g’ less. I do understand: it’s not an easy th<strong>in</strong>g to do.”<br />

4.1. PRESENTATION HANDOUT: You will have to be extremely well-discipl<strong>in</strong>ed, as you will have between 40–45<br />

m<strong>in</strong>utes—not a whit more or less—to present all your <strong>in</strong>formation. To encourage your efforts <strong>in</strong> this regard,<br />

you will be required to have a handout—a handout which will be worth nearly as much as the presentation<br />

itself. Make no mistake: craft<strong>in</strong>g an effective handout is an art. It should summarize diverse data, enable your<br />

audience to grasp the thrust of your argument at a glance, and help them remember your ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts thereafter.<br />

If you have any doubts about the importance I place on these time-<strong>in</strong>tensive creations, simply consider the<br />

material <strong>in</strong> your hand.

Handouts will be graded as follows:<br />

A. Analytical Content<br />

1. Passages/Scenes Considered (5 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 8<br />

• Does the handout accurately reflect the contents of the presentation?<br />

• Is there a clear connection between the passages/scenes treated <strong>in</strong> the handout and those analyzed <strong>in</strong><br />

the presentation?<br />

• Do the examples treated <strong>in</strong> the handout proceed <strong>in</strong> the same order as those <strong>in</strong> the presentation?<br />

2. Summary of Po<strong>in</strong>ts (35 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

Does the handout clearly summarize the student’s po<strong>in</strong>ts regard<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

• the context of the passages/scenes exam<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

• difficult vocabulary or other complexities <strong>in</strong> the passages<br />

• the significance of the passages/scenes: how they further the plot, give us <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to characters,<br />

reflect themes or patterns elsewhere <strong>in</strong> the work, and so forth<br />

3. Conclusions (10 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

• Does the handout present the audience with a manageable list of po<strong>in</strong>ts to remember?<br />

• How does the handout help the audience remember those po<strong>in</strong>ts?<br />

B. Format<br />

1. Clarity and Style (10 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

• Does the handout clearly present the analysis of each example?<br />

• Is the layout and style of the handout crisp, professional, and aesthetically crafted, or has it been<br />

thrown together <strong>in</strong> haste on an old manual typewriter?<br />

2. Logical flow (10 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

• Did the student’s treatment of examples flow <strong>in</strong> a logical order?<br />

• Did he provide clear transitions between his po<strong>in</strong>ts, or did his comments seem to dart about at random?<br />

• In treat<strong>in</strong>g his examples, did the student build a case or draw some overall conclusions about the<br />

director’s approach to the play at hand?<br />

3. Organization (10 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

• Is the <strong>in</strong>formation on the handout squooshed together or organized <strong>in</strong>to clearly-identifiable logical<br />

sections?<br />

• Does the format allow the reader easily to follow the progression of the student’s argument?<br />

4. Audience Engagement (5 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

• Does the handout require the audience to fill <strong>in</strong> key bits of <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> the course of the<br />

presentation, or otherwise encourage them to pay attention and stay awake?<br />

• Does the handout use humor or otherwise unexpected elements to engage the audience and keep them<br />

<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> the presentation?<br />

4. Creativity (15 po<strong>in</strong>ts)<br />

• Does the handout <strong>in</strong>corporate visual elements such as pictures, diagrams, or screen-captures that help<br />

to illustrate the student’s po<strong>in</strong>ts and guide the audience to key scenes or aspects of scenes to which<br />

they should pay particular attention?<br />

• Is the overall concept for the handout orig<strong>in</strong>al, hip, cool, suave, far out, or positively pulchritud<strong>in</strong>ous<br />

(dude)?<br />

(100 po<strong>in</strong>ts total)<br />

4.2. TIMETABLE & RESEARCH: While you will have the chance to choose the section of Beowulf on which you<br />

will present, you should do so quite soon <strong>in</strong> the semester: you will likely need to rely heavily on <strong>in</strong>terlibrary<br />

loan for your secondary resources (journal articles and/or books perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to your subject), and these will take<br />

some time to arrive. As a rule, you should concentrate on more recent works (pr<strong>in</strong>ted, say, <strong>in</strong> the last ten years),<br />

as older material may well have been superseded by later scholarship. In addition, you should avoid bas<strong>in</strong>g your<br />

formal papers on <strong>in</strong>ternet sources unless they derive from refereed (scholar-approved) journals or other

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 9<br />

established pr<strong>in</strong>ted work. It’s a matter of perceived academic credibility: you want your readers to have no<br />

doubt but that you are work<strong>in</strong>g from the most reputable of sources.<br />

Where do I go to f<strong>in</strong>d credible sources, you ask?<br />

• Bibliographies of scholarly studies of Beowulf (and oh yes, such studies are numerous) <strong>in</strong>clude:<br />

o Short, Douglas D., Beowulf Scholarship: An Annotated Bibliography (New York: Garland, 1980);<br />

o Hasenfratz, Robert J., Beowulf Scholarship: An Annotated Bibliography, 1979-1990 (New York:<br />

Garland, 1993);<br />

o The Old English Newsletter, published for the Old English Division of the Modern Language<br />

Association of America; it provides an annual bibliography of scholarly publications on Old English<br />

language and literature (now onl<strong>in</strong>e at http://www.oenewsletter.org/OENDB/log<strong>in</strong>.php), and<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes an annotated “Year’s Work <strong>in</strong> Old English”;<br />

o Anglo-Saxon England, the premier journal for Anglo-Saxon studies, published by Cambridge<br />

University Press, <strong>in</strong>cludes an annual bibliography of scholarship <strong>in</strong> Anglo-Saxon studies;<br />

o Greenfield, Stanley B. and Fred C. Rob<strong>in</strong>son, A Bibliography of Publications on Old English<br />

Literature, from the Beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs Through 1972 (Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1980) covers<br />

literature prior to the OEN and ASE bibliographies.<br />

• Through the Biola Library website at http://www.biola.edu/adm<strong>in</strong>/library/DataBase.cfm, we have access<br />

to three key databases about which you should know:<br />

o An <strong>in</strong>valuable resource for research <strong>in</strong> the humanities <strong>in</strong> general is the Modern Language<br />

Association’s Bibliography. At the Library’s database page, scroll down to MLA International<br />

Bibliography, which will take you to FirstSearch; under “Jump to Advanced Search: Select a<br />

Database,” choose MLA.<br />

o From the Library’s database page, also check out the Literature Resource Center. Search for<br />

Beowulf (or a more specific term), click on the “Literary Criticism” tab, and peruse articles onl<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

o For books as opposed to articles, try the WorldCat database, also found <strong>in</strong> FirstSearch.<br />

• And f<strong>in</strong>ally, check out the back of Heaney’s translation and Jack’s edition of Beowulf: helpful<br />

bibliographies may be found there<strong>in</strong>.<br />

5. BIBLIOGRAPHIC BEOWULF PROJECT: Flow<strong>in</strong>g from your research above, this semester will also provide you<br />

the opportunity to engage and to contribute to the current scholarly dialogue on Beowulf. In keep<strong>in</strong>g with our<br />

textual focus, however, rather than exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g themes, cultural elements, or theological/philosophical ideas <strong>in</strong><br />

the work as a whole—all subjects we’ll discuss <strong>in</strong> depth <strong>in</strong> class—this paper will call you to focus on problems<br />

posed by a particular set of l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> the poem. You may wish to explore the debate over that problematic read<strong>in</strong>g<br />

[Mod]thryth[o] (cruel queen or misunderstood quality?); exam<strong>in</strong>e the so-called “palimpsest page” and its<br />

enormous ramifications regard<strong>in</strong>g Beowulf’s date; attempt to reconstruct a passage damaged by boil<strong>in</strong>g steam,<br />

knives, and fire; or what have you. We’ll encounter any number of <strong>in</strong>trigu<strong>in</strong>g dilemnas posed by the manuscript<br />

and/or text <strong>in</strong> the course of our read<strong>in</strong>g; keep your eye out for a bit of the story that particularly <strong>in</strong>terests you.<br />

5.1. ANNOTATED EDITION: The first phase of your research will be to collect some twenty articles that address<br />

aspects of the l<strong>in</strong>es you have chosen. You’ll then produce summaries of these articles—or rather, the po<strong>in</strong>ts they<br />

make about your passage—which you’ll reproduce <strong>in</strong> conjunction with a critical edition of the Old English text.<br />

We’ll talk further about what a critical edition entails—I’ll give you part of a text I’m edit<strong>in</strong>g for a National<br />

Endowment for the Humanities project, for example—but <strong>in</strong> general, you’ll need to account for problems <strong>in</strong> the<br />

manuscript (such as letters or words that have been lost), show how other editions or translations have<br />

addressed these problems, and then offer your own reconstruction of the passage, provid<strong>in</strong>g a conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g case<br />

for your solutions. In the process, you’ll be wrestl<strong>in</strong>g with a fundamental issue that confronts all crafters of<br />

critical editions: how to pack all the <strong>in</strong>formation you want to convey <strong>in</strong>to the limitations of a page. Do you<br />

surround the critical text with your annotations? Put your commentary <strong>in</strong>to the marg<strong>in</strong>? Make use of a multilayered<br />

apparatus for variant read<strong>in</strong>gs? Place translation and orig<strong>in</strong>al text on fac<strong>in</strong>g pages, with additional notes<br />

relegated to an appendix? Take a stab at it, and see how best you can balance content and clarity.

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 10<br />

5.3. RESEARCH PAPER: Once the Annotated Edition is complete—<strong>in</strong> other words, once the evidence related to<br />

your passage has been assembled and organized—you’ll seek to argue a cautious, precise, narrow thesis that<br />

rises from, reacts to, and <strong>in</strong>terprets that evidence. I will gladly discuss ideas for your thesis with you<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividually dur<strong>in</strong>g the semester; two tools to help ref<strong>in</strong>e the thrust and scope of your argument, <strong>in</strong>clude:<br />

5.3.1. GUIDELINES FOR LOGICAL ARGUMENTATION, GRAMMAR, AND MECHANICS (see the Appendix below);<br />

5.3.2. LOGICAL OUTLINE: To make sure you have the chance to get feedback on your paper-proposal, three<br />

weeks before the deadl<strong>in</strong>e you will submit a logical outl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> which you set out your thesis, ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts, and<br />

the evidence (direct quotations and summaries from your research) which you’ll use to support your argument.<br />

The outl<strong>in</strong>e may flow as follows:<br />

Introductory Paragraph<br />

Summary of Ma<strong>in</strong> Po<strong>in</strong>ts<br />

Thesis Statement<br />

First Ma<strong>in</strong> Po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

Textual Evidence A (quotation or summary)<br />

Commentary on Textual Evidence A (tell me how it furthers your argument)<br />

Textual Evidence B (quotation or summary)<br />

Commentary on Textual Evidence B<br />

Textual Evidence C (quotation or summary)<br />

Commentary on Textual Evidence C<br />

Second Ma<strong>in</strong> Po<strong>in</strong>t . . .<br />

Third Ma<strong>in</strong> Po<strong>in</strong>t . . .<br />

Conclusion (recapitulation of ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts and thesis)<br />

If the logic of the paper is weak at certa<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts, or if the thesis is a bit murky overall, this outl<strong>in</strong>e<br />

should reveal such th<strong>in</strong>gs and help us to plot a solution before the Day of Reckon<strong>in</strong>g comes.<br />

NOTE: The Logical Outl<strong>in</strong>e and the Annotated Edition will be due <strong>in</strong> close proximity (<strong>in</strong>deed, as it<br />

stands, they are booked for the same day). One reason for such schedul<strong>in</strong>g is to encourage you to be<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g through your evidence and mak<strong>in</strong>g connections as you compile your Edition; it will, however,<br />

mean a considerable amount of work if you haven’t been discipl<strong>in</strong>ed beforehand. Don’t leave any of this<br />

until the last m<strong>in</strong>ute, eez whatta eyem say<strong>in</strong> to yooz.<br />

6. THE TRIALS<br />

On the first day of class, Wyrd—Implacable Fate or Div<strong>in</strong>e Providence, a concept of key import <strong>in</strong> Beowulf—<br />

shall determ<strong>in</strong>e your division <strong>in</strong>to three Germanic Tribes. These will be your families, your battle-shields, the<br />

keepers of your honor, your kith and k<strong>in</strong>. Loyalty to your R<strong>in</strong>g-Giver and comitatus—the circle of thanes or<br />

warriors that surround him—will result <strong>in</strong> glory; treachery will br<strong>in</strong>g ignom<strong>in</strong>ious, last<strong>in</strong>g shame. Like Beowulf<br />

himself, you will be given the opportunity to prove your worth and to br<strong>in</strong>g your tribe renown <strong>in</strong> a series of<br />

<strong>in</strong>sidious trials, as so:<br />

6.1. TRIAL BY VENDETTA<br />

The world of Beowulf is populated by a complex series of k<strong>in</strong>gs, queens, warriors, and wives belong<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

various Germanic tribes, the tensions between which are a convoluted but essential <strong>in</strong>gredient of the story. One<br />

could simply be required to sit down and memorize lists of names, of course, but another approach seems both<br />

more appeal<strong>in</strong>g and more <strong>in</strong> keep<strong>in</strong>g with the spirit of this warrior culture: the blood feud.<br />

The goal of Vendetta is to kill off the members of the other two tribes by correctly identify<strong>in</strong>g them; this is done<br />

by pos<strong>in</strong>g a series of carefully-worded and precise questions that can be answered Yes or No (or, on rare<br />

occasions, “Yes and No”). Questions and answers should be posted to the class’ Bubbs folder (under “<strong>Dr</strong>.

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 11<br />

Kleist” <strong>in</strong> the English Department folder): questions must be submitted electronically by noon prior to any<br />

given class; answers must be posted with<strong>in</strong> 24 hours thereafter. As you know, Bubbs <strong>in</strong>cludes a time stamp on<br />

every post, so it will be clear if these deadl<strong>in</strong>es are not met, and penalties will be assessed accord<strong>in</strong>gly (see<br />

[6.1.5.] VENDETTA/TRIAL PARTICIPATION below). Such a measure isn’t <strong>in</strong>tended as a cudgel, but simply as a<br />

goad to keep the game mov<strong>in</strong>g: a team’s progress, after all, depends on a swift <strong>in</strong>terchange of <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

NOTE: Questions and accusations cannot be posted until 24 hours after the previous round ends. In<br />

Round one, for example, all questions must be submitted by noon on Thursday 31 August. Individuals<br />

have until noon on Wednesday 1 September to answer. At 12.01pm on Wednesday, the next round’s<br />

questions or accusations may be posted.<br />

All characters will be assigned numbers to hide their true identities; <strong>in</strong> the subject-l<strong>in</strong>e of your message,<br />

therefore, you should note the author and <strong>in</strong>tended recipient of the query: “A5 question for C8” and “B3 answer<br />

to C1” would thus <strong>in</strong>dicate an exchange between the fourth member of the York Faction and the thirteenth<br />

member of the Lancaster Faction. Messages lack<strong>in</strong>g this author/recipient <strong>in</strong>formation will be declared void<br />

and not counted. Why? First, for clarity’s sake: every person will be scann<strong>in</strong>g for his or her mail. In a game<br />

where hundreds of questions and answers will be exchanged, clarity is crucial. Second, because of strategy: if<br />

A6 persistently goes after B9, it may be <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terests of B9 (and his Tribe) to try to take A6 out. The shrewd<br />

team will spread their questions around: if they suspect B9 of be<strong>in</strong>g a R<strong>in</strong>g Giver or a Shadow Warrior (and<br />

thus worth extra po<strong>in</strong>ts [see below]), a Tribe may all target B9 without mak<strong>in</strong>g any one of them becom<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

target himself. Make sense?<br />

When you’re confident of the identity of a particular person, you need to post a message with the subject l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

“ACCUSATION!” In as flowery, witty, and <strong>in</strong>sult<strong>in</strong>g language as possible, accuse your opponent of be<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

particular member of another tribe. If you are right, your opponent dies, and your team will ga<strong>in</strong> the wergeld, or<br />

life value, assigned to that person. However, tread carefully, for a false accusation will result <strong>in</strong> your own death<br />

and the transference of your own wergeld to the other team.<br />

NOTE: Given the complex alliances of certa<strong>in</strong> figures dur<strong>in</strong>g this period, it is not <strong>in</strong>conceivable that the<br />

same character could be found <strong>in</strong> multiple tribes. Now, were you to f<strong>in</strong>d yourself with a doppelganger or<br />

evil tw<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the enemy camp, clearly that tw<strong>in</strong> would be responsible for any treacherous behavior your<br />

character might have historically committed aga<strong>in</strong>st the True and Noble Bloodl<strong>in</strong>e to which you belong:<br />

your classmates can thus embrace you while cast<strong>in</strong>g condemnation (along with you) on your other,<br />

nefarious half. However, were you <strong>in</strong>advisably to unmask and thus assass<strong>in</strong>ate your evil opposite, you<br />

yourself would die <strong>in</strong> the process. This is another place where Tribes are useful: let one of your<br />

colleagues plunge the dagger <strong>in</strong>.<br />

TECHNICAL NOTE: If one is the recipient of an assass<strong>in</strong>ation-attempt, he must respond both to the<br />

accusation and to any other questions that might (for whatever reason) have been posed to him. If the<br />

accusation aga<strong>in</strong>st him is accurate and he dies, his own accusations (if accurate) still br<strong>in</strong>g about the<br />

death of his adversaries: it’s as though he slays his enemies even <strong>in</strong> the act of be<strong>in</strong>g sla<strong>in</strong> (even as the<br />

soldiers of Joab and Abner, plung<strong>in</strong>g their daggers <strong>in</strong>to one another). To be specific: as long as (1) a<br />

correctly-accused character gives up the ghost (i.e., acknowledges the accuracy of the accusation) <strong>in</strong> the<br />

24-hour period follow<strong>in</strong>g the round <strong>in</strong> which the accusation was made, AND (2) the character makes his<br />

accusation before giv<strong>in</strong>g up the ghost, THEN a character may accuse ONE opponent with his dy<strong>in</strong>g<br />

breath. Such a rul<strong>in</strong>g seeks both to acknowledge the potential potency of one’s f<strong>in</strong>al, heroic efforts—to<br />

which Beowulf can well attest—and to avoid random wounds caused by wild flail<strong>in</strong>g rigor mortis.<br />

6.1.1. IDENTITIES, WERGELDS, RING-GIVERS, & SHADOW WARRIORS<br />

Each member of the class will be given both primary and secondary identities; each Tribe therefore is play<strong>in</strong>g<br />

eight characters that must be unmasked. Individuals’ primary identity must be discovered before their secondary

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 12<br />

identity may be explored; opponents must therefore conf<strong>in</strong>e their questions to the former before seek<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

uncover the latter.<br />

Each character is assigned a wergeld (literally, “man-money”), or life-value, which is reta<strong>in</strong>ed by the player’s<br />

Tribe if that character is alive at game’s end, and which is won by an oppos<strong>in</strong>g Tribe if the character is correctly<br />

identified (and thus assass<strong>in</strong>ated). Individuals’ secondary identities are often more obscure than their primary<br />

ones, but are worth gett<strong>in</strong>g to, as they are worth twice as much—500 rather than 250 po<strong>in</strong>ts, for example.<br />

Each Tribe will have a R<strong>in</strong>g-Giver, who will be responsible for reward<strong>in</strong>g faithful and exemplary service to the<br />

Tribe throughout the semester <strong>in</strong> verbal and concrete ways. All due honor and ceremony may attend the R<strong>in</strong>g-<br />

Giver, as his thanes judge it commensurate with his or her merit. The R<strong>in</strong>g-Giver will be a primary rather than a<br />

secondary identity, and his wergeld will be worth double that of his companions—500 rather than 250 po<strong>in</strong>ts.<br />

Each Tribe will also have a Shadow Warrior, an <strong>in</strong>dividual whose secondary identity may prove slightly more<br />

difficult to identify than that of his companions. The Shadow Warrior’s wergeld is likewise double—1000<br />

rather than 500 po<strong>in</strong>ts. F<strong>in</strong>d and exterm<strong>in</strong>ate him.<br />

6.1.2. BONUSES & POINTS<br />

Bonus po<strong>in</strong>ts are awarded <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g manner:<br />

+ 500 for correctly identify<strong>in</strong>g a character after 1 question<br />

+ 400 for correctly identify<strong>in</strong>g a character after 2 questions<br />

+ 300 for correctly identify<strong>in</strong>g a character after 3 questions<br />

+ 200 for correctly identify<strong>in</strong>g a character after 4 questions<br />

+ 100 for correctly identify<strong>in</strong>g a character after 5 questions<br />

NOTE: No player amasses <strong>in</strong>dividual po<strong>in</strong>ts; rather, he scores po<strong>in</strong>ts for his Tribe and for his class. (This means,<br />

for example, that if you don’t want to identify someone on the oppos<strong>in</strong>g team—be<strong>in</strong>g, perhaps, that evil<br />

character’s virtuous tw<strong>in</strong>—someone else <strong>in</strong> your Tribe can make the identification without you los<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts.)<br />

If the class feels that the other team is gett<strong>in</strong>g close to identify<strong>in</strong>g a major player <strong>in</strong> the game—their R<strong>in</strong>g Giver<br />

or Shadow Warrior, for example—they may purchase an exemption or temporary immunity for that character<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the class treasury. Exemptions are limited periods of time where no questions may be asked of and no<br />

accusations made towards a particular person. The cost of the exemption is directly related to the worth of the<br />

character and the length of the exemption. To wit:<br />

One-Turn Exemptions COST Two-Turn Exemptions COST Three-Turn Exemptions COST<br />

250-wergeld character 75 250-wergeld character 125 250-wergeld character 200<br />

500-wergeld character 150 500-wergeld character 275 500-wergeld character 400<br />

1000-wergeld character 300 1000-wergeld character 550 1000-wergeld<br />

800<br />

character1000-wergeld<br />

The Tribe treasury is the comb<strong>in</strong>ed worth of all players currently alive on your team, plus any wergeld and<br />

bonus po<strong>in</strong>ts accrued by identify<strong>in</strong>g members of the opposite team. The only person who may authorize use of<br />

the class treasury is the R<strong>in</strong>g-Giver. If the R<strong>in</strong>g-Giver wishes to buy an exemption, he or she must e-mail our<br />

Illustrious Teach<strong>in</strong>g Assistant, Ms. Michael D<strong>in</strong>smoor (michael.k.d<strong>in</strong>smoor@bubbs.biola.edu) and request the<br />

exemption be made.<br />

STRATEGY NOTE: The class may spend more po<strong>in</strong>ts than are <strong>in</strong> the treasury at a given po<strong>in</strong>t; at the end of the<br />

game, however, any po<strong>in</strong>ts they have spent do count aga<strong>in</strong>st them. In other words, if early <strong>in</strong> the round the<br />

class buys an exemption for 550 po<strong>in</strong>ts, but at the round’s end only has 250 po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the treasury (most of<br />

the class hav<strong>in</strong>g been killed off), the class’ f<strong>in</strong>al score is – 300 po<strong>in</strong>ts. Conversely, however, if the class<br />

spends 300 po<strong>in</strong>ts on a 1000-wergeld character who survives, the class is up 700 po<strong>in</strong>ts. Choose wisely.

6.1.3. VENDETTA TIMETABLE<br />

Th Aug 31 Round 1 Th Sept 14 Round 5<br />

T Sept 5 Round 2 T Sept 19 Round 6<br />

Th Sept 7 Round 3 Th Sept 21 Round 7<br />

T Sept 12 Round 4 T Sept 26 Round 8<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 13<br />

6.1.4. ADDITIONAL TRIALS<br />

However bloody this Trial by Vendetta may be, the quest for Tribal Supremacy is by no means over. Three<br />

more Trials await, <strong>in</strong>terspersed over the course of the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g weeks of the semester. First, you will be<br />

required to prove your prowess <strong>in</strong> the TRIAL BY VOICE. This Trial will comprise three challenges, <strong>in</strong> which at<br />

least one team member must compete: the Duel of the Scops (or Bards), the Duel of the Flyt<strong>in</strong>g (verbal wordcombat),<br />

and the Duel of the Boast. All three areas, as we will see, test skills <strong>in</strong>dispensable to the world of<br />

Beowulf. Second, there is the TRIAL BY COMBAT, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g both selected Champions from each group and pan-<br />

Tribal mayhem. By way of preparation, an Anglo-Saxon Warfare Workshop will <strong>in</strong>troduce you to different<br />

martial methodologies of Germanic tribes. F<strong>in</strong>ally, there is the TRIAL BY WATER, which will replicate such<br />

formidable struggles as that between Beowulf and Breca, Beowulf and the Mere-Monsters, and Vik<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Longship Warfare.<br />

At semester’s end, the Tribe scor<strong>in</strong>g highest will be awarded tribute, honor, and the Ultimate Vik<strong>in</strong>g Trophy at<br />

an Anglo-Saxon Feast celebrat<strong>in</strong>g the triumphs and travails of all participants.<br />

6.1.5. VENDETTA/TRIAL PARTICIPATION<br />

Success <strong>in</strong> the these Trials will require decided <strong>in</strong>vestment: <strong>in</strong> the Vendetta, for example, you will be required to<br />

know thyself (yea verily) and know the character, actions, and affiliations of a fairly wide web of allies and<br />

enemies. In terms of your grade, however, the requirements are simple: First, <strong>in</strong> the Vendetta, <strong>in</strong>dividuals must<br />

pose sixteen questions—no more and no less—to members of the sculldugerous Other Tribes. Questions must<br />

be submitted electronically prior to any given class, with a maximum of two questions be<strong>in</strong>g permitted per<br />

class session. Should you be assass<strong>in</strong>ated dur<strong>in</strong>g a phase of the game, you will still be expected to help your<br />

Tribe <strong>in</strong>formally by bra<strong>in</strong>storm<strong>in</strong>g about the identify of enemy characters, but you will no longer be allowed to<br />

pose questions to the other class; <strong>in</strong> terms of your grade, therefore, should you be sla<strong>in</strong>, you will be treated as<br />

though you had fulfilled your quota of sixteen questions.<br />

Second, <strong>in</strong>dividuals must answer with<strong>in</strong> 24 hours any questions directed at them. Questions are to be answered<br />

Yes, No, or Yes and No, the last only be<strong>in</strong>g used when absolutely necessary. Please note: you will be held<br />

accountable for the accuracy of your answers. Tribes may challenge answers given by members of the opposite<br />

class if they feel themselves to have been misled. Individuals may defend their reason<strong>in</strong>g beh<strong>in</strong>d an answer; if<br />

the challenge is upheld, however, so that an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s answer is deemed <strong>in</strong>accurate or otherwise<br />

<strong>in</strong>appropriate, it will be ruled void and treated as if it had never been submitted—with the appropriate penalty<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g leveled <strong>in</strong> consequence.<br />

Reward for pos<strong>in</strong>g and answer<strong>in</strong>g all questions on time, and for participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the other Trials: an A (94%) for<br />

this portion of your grade.<br />

Penalty for fail<strong>in</strong>g to pose or answer questions on time: – 3% (from 94%) for each question not submitted<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the requisite period. As with absences, should emergencies arise, not to worry: just talk to me (preferably<br />

<strong>in</strong> advance). Your excuse, however, should be a good one, as the smooth runn<strong>in</strong>g of these contests depends on<br />

your active and timely participation.

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 14<br />

Look<strong>in</strong>g forward to delv<strong>in</strong>g with you <strong>in</strong>to the world of heroes, dragons, and monsters that is Beowulf, I rema<strong>in</strong><br />

Your servant,<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. Vonk<br />

So—<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> babysitt<strong>in</strong>g?<br />

MAP I: The World of Beowulf MAP II: Modern Political Boundaries<br />

Gratuitous Family Pictures.<br />

(Be warned: there may be more!)

1. Work through your passage sentence by sentence. 1<br />

ADVICE FOR TRANSLATION<br />

2. Identify the major parts of each sentence, start<strong>in</strong>g with the subject and the verb.<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 15<br />

3. To dist<strong>in</strong>guish the subject from other nouns like direct and <strong>in</strong>direct objects, look at the case of each word.<br />

Thus, <strong>in</strong> the sentence “The boy hit the ball with the bat <strong>in</strong>to the neighbor’s w<strong>in</strong>dow”<br />

—”the boy” is the subject or agent of the action (nom<strong>in</strong>ative);<br />

—”the ball” is the direct object of the action (accusative);<br />

—”the w<strong>in</strong>dow” is the <strong>in</strong>direct object of the action (dative);<br />

—”the bat” is the <strong>in</strong>strument by which the action is accomplished (<strong>in</strong>strumentive);<br />

—”the neighbor” is the owner or possessor of the w<strong>in</strong>dow (genitive).<br />

In general terms, then,<br />

—genitives are translated us<strong>in</strong>g “of” or “ ‘s “<br />

(“Hoces dohtor” = “Hoc’s daughter” or “the daughter of Hoc” [Beowulf 1076])<br />

—datives are translated us<strong>in</strong>g “to” or “for”;<br />

(“F<strong>in</strong> Hengeste benemde” = “F<strong>in</strong>n declared to Hengest” [Beowulf 1096])<br />

—<strong>in</strong>strumentals are translated us<strong>in</strong>g “<strong>in</strong>” or “with”;<br />

(“sorge mændon” = “they spoke with sorrow” [Beowulf 1149])<br />

—nom<strong>in</strong>atives and accusatives are translated straightforwardly<br />

(“scyld scefte oncwyð” = “shield answers shaft”, that is, the shields deflect oncom<strong>in</strong>g arrows<br />

[Fragment 7])<br />

4. This said, watch out for verbs that “take” strange cases—<strong>in</strong> other words, that require the word associated with<br />

them to use a case that you wouldn’t expect. For example:<br />

—we might expect “neosian” (to go TO [somewhere]) to take a dative (e.g., “[to go] TO the ship”), but<br />

it doesn’t; it takes a genitive: “wica neosian” (“to go to [their] homes” [Beowulf 1125])<br />

—we might expect “befeallen” (“deprived OF”) to take a genitive, but it takes a dative <strong>in</strong>stead:<br />

“freondum befeallen” (“deprived of friends” [Beowulf 1125])<br />

—we might expect “forwyrnan” (“to refuse”) to take an accusative (e.g., “to refuse the request”), but it<br />

takes a genitive <strong>in</strong>stead: “he ne forwyrnde woroldrædenne” (“he did not refuse the world’s-law”<br />

[Beowulf 1142])<br />

5. Prepositions, too, take specific cases:<br />

—mid (“with, among”) can take the accusative, <strong>in</strong>strumentive, or (as here) dative case<br />

(“þæs wæron MID EOTENUM ecge cuðe” = “the edges of it were well-known AMONG THE<br />

JUTES” [Beowulf 1145])<br />

—æt (“at, by, <strong>in</strong>, on, with”) usually takes the dative case<br />

(“Ne gefrægn ic nǽfre wurþlicor ÆT wera HILDE” = “Never have I heard of worthier men IN<br />

BATTLE”[Fragment 37])<br />

—þurh (“through, by means of, with”) takes the dative, genitive, or (as here) accusative case<br />

(“ne ÞURH INWITSEARO æfre gemænden” = “nor should they ever compla<strong>in</strong> WITH ARTFUL<br />

INTRIGUE” [“<strong>in</strong>witsearo” be<strong>in</strong>g a neuter with no end<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the accusative] [Beowulf 1101])<br />

6. Word-order, especially <strong>in</strong> poetry (as <strong>in</strong> our texts), is by no means as important as it is <strong>in</strong> Modern English.<br />

While for us, “the dog ate his food” is not quite the same as “the food ate his dog,” <strong>in</strong> Old English it can<br />

be phrased either way—you just dist<strong>in</strong>guish the subject from the object by their cases.<br />

Thus, you might f<strong>in</strong>d the verb (for example) at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

1 (You might keep <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d that nearly all the punctuation you see is not <strong>in</strong> the manuscripts and has been added by editors, so that one<br />

might debate where a particular sentence ends and the next beg<strong>in</strong>s, but that’s an issue we’ll address later <strong>in</strong> the semester.)

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 16<br />

Wand to wolcnum wælfyra mæst<br />

(“The greatest of funeral flames curled to the clouds” [Beowulf 1119])<br />

or at the end<br />

sume on wæle crungon<br />

(“Some [typical Old English understatement; = MANY] fell <strong>in</strong> the slaughter” [Beowulf 1113])<br />

7. Old English, and especially Old English poetry, loves apposition, that is, multiple references to the same<br />

person, th<strong>in</strong>g, or event <strong>in</strong> varied terms: “The Sea-farer, noble of birth, frigid of limbs, sat <strong>in</strong> his boat, the<br />

sea-scythe, breaker of waves, stout voyage-companion, and composed this verse, wrestl<strong>in</strong>g with words,<br />

because he was bored stiff and couldn’t th<strong>in</strong>k of anyth<strong>in</strong>g better to do.”<br />

Don’t worry if there is lots of repetition, or gaps between phrases referr<strong>in</strong>g to the same<br />

person/th<strong>in</strong>g/event.<br />

Gewiton him ða wigend wica neosian<br />

The warriors departed to go to their dwell<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

freondum befeallen, Frysland geseon,<br />

bereft of their friends, to see Friesland,<br />

hamas ond heaburh.<br />

[their] homes and strong-hold. (Beowulf 1125-7a)<br />

Here, “wigend” (warriors) are further described as “freondum befeallen” (bereft of their friends); they<br />

depart “neosian” (to go) and “geseon” (to see) Friesland, that is, their “hamas ond heaburh” (homes and<br />

strong-hold).<br />

And that, I th<strong>in</strong>k, is plenty for the moment.

PRONUNCIATION<br />

Kleist, Beowulf (<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong>) 17<br />

VOWELS OE example CONSONANTS<br />

a like MoE (Modern English) habban (to have) ċ like MoE chalk (before e and i)<br />

aha or not<br />

c like MoE call (before a, o, u, and y)<br />

ā like MoE aha or father stān (stone) cg like MoE bridge<br />

æ like MoE hat æt (at/near/<strong>in</strong>/upon) ff like MoE father<br />

ǽ like MoE bad or airy dǽd (deed/act) ġ like MoE yield (before e and i)<br />

e like MoE met stelan (to steal) g like MoE good (before a, o, u, and y)<br />

ē like MoE fate dēman (to judge) g like German sagen (after/between a, o, u)<br />

i like MoE bit biton (they bit) h like MoE hand (<strong>in</strong>itially before vowels)<br />