Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ing classical geometric "projections." <strong>The</strong> explicit geometric<br />

tradition <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pasteur</strong>, who was a highly talented amateur<br />

painter in the tradition <strong>of</strong> Rembrandt, stretches back through<br />

the school <strong>of</strong> Monge, via Leibniz, Huygens, and Euler, to<br />

Kepler and Leonardo. This scientific tradition can be most<br />

efficiently traced by looking for its characteristic trait <strong>of</strong><br />

making physical models—actual geometric constructions—to<br />

demonstrate the way in which processes work in<br />

nature.<br />

<strong>Pasteur</strong>'s famous wooden models <strong>of</strong> left-handed and righthanded<br />

tartrate crystals were firmly embedded in this geometric<br />

approach and gave birth to the widespread tradition<br />

<strong>of</strong> biomolecular model-building in the 20th century. <strong>The</strong><br />

mathematical high point <strong>of</strong> this approach <strong>of</strong> synthetic or<br />

constructive geometry, in fact, was flourishing at the University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Gottingen in Germany through the work <strong>of</strong> Jakob<br />

Steiner and his student, Bernhard Riemann, simultaneously<br />

with <strong>Pasteur</strong>'s own work.<br />

<strong>Pasteur</strong>'s method was explicitly derived from Gaspard<br />

Monge's "descriptive geometry" as applied to optics by a<br />

generation <strong>of</strong> scientists trained at Monge's Ecole Polytechnique<br />

in the late 18th century (Arago, Fresnel, Biot, and<br />

Malus) and their close German collaborators (Alexander<br />

von Humboldt and Gottingen's Eilhard Mitscherlich). <strong>The</strong>se<br />

were <strong>Pasteur</strong>'s immediate scientific teachers and forebears.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir work established the modern scientific understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> light beam optics and spectroscopy on a firm geometrical<br />

and nonempiricist footing. Demonstrating a true<br />

Keplerian heritage, most <strong>of</strong> these scientists were leading<br />

geometers and astronomers: Arago was the director <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Paris Observatory from 1813-1846; Biot from 1808 onwards<br />

was pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> astronomy at the University <strong>of</strong> Paris; Fresnel<br />

based his discoveries <strong>of</strong> transverse waves, diffraction,<br />

and interference phenomena on observations <strong>of</strong> stellar aberrations<br />

(see chronology).<br />

<strong>Pasteur</strong> established that there was a direct mapping relationship<br />

between the left-handedness or right-handedness<br />

<strong>of</strong> biological products when in their crystal state or in solution<br />

and their action on the rotary power <strong>of</strong> polarized<br />

light. <strong>The</strong>re are certain characteristic features <strong>of</strong> the intrinsic<br />

geometries <strong>of</strong> living space that are directly responsible<br />

for its ability to absorb and reorganize light energy (electromagnetic<br />

radiation) for its own growth and self-reproduction.<br />

Thus, it can be proven geometrically that neither living<br />

processes, nor the universe in which living processes exist,<br />

obey the Second Law <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong>rmodynamics. Such processes<br />

are inherently negentropic, a term introduced by economist<br />

Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. to describe the self-developing<br />

process in the universe as a whole, which is coherent<br />

with the development <strong>of</strong> living systems.'<br />

In <strong>Pasteur</strong>'s terminology, the nature <strong>of</strong> our nonequilibrium<br />

universe to progress in the direction <strong>of</strong> ever more<br />

ordered states—namely, to accomplish work and "grow"<br />

away from equilibrium—is its characteristic "dissymmetry."<br />

As he wrote in 1874:<br />

<strong>The</strong> universe is a dissymmetrical totality, and I am<br />

inclined to think that life, such as it is manifested to us,<br />

is a function <strong>of</strong> the dissymmetry <strong>of</strong> the universe or the<br />

consequences which it produces.<br />

<strong>Pasteur</strong> was conscious <strong>of</strong> the fact that his approach to<br />

science was in total contrast to the prevailing doctrine <strong>of</strong><br />

Positivism, a philosophical outlook that denies all reality<br />

but those "facts" empirically verifiable through sense certainty.<br />

During the early 1880s, in fact, <strong>Pasteur</strong> engaged in<br />

open polemical warfare against the champion <strong>of</strong> Positivism,<br />

Auguste Comte. <strong>Pasteur</strong> focused upon the devastating flaw<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Positivist doctrine in its inability to account for creative<br />

discovery:<br />

Positivism does not take into account the most important<br />

<strong>of</strong> positive notions, that <strong>of</strong> the Infinite. . . .<br />

What is beyond? <strong>The</strong> human mind, actuated by an invincible<br />

force, will never cease to ask itself: what is<br />

beyond?. . . He who proclaims the existence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Infinite—and none can avoid it—accumulates in that<br />

affirmation more <strong>of</strong> the supernatural than is to be found<br />

in all the miracles <strong>of</strong> all the religions; for the notion <strong>of</strong><br />

the Infinite presents that double character that it forces<br />

upon us and yet is incomprehensible.<br />

Today's scientific frontiers are filled with examples <strong>of</strong><br />

numerous <strong>Pasteur</strong>ian effects. Researchers engaged in<br />

energy-dense plasma experiments and high-energy particle<br />

physics have repeatedly observed "twisted" structures<br />

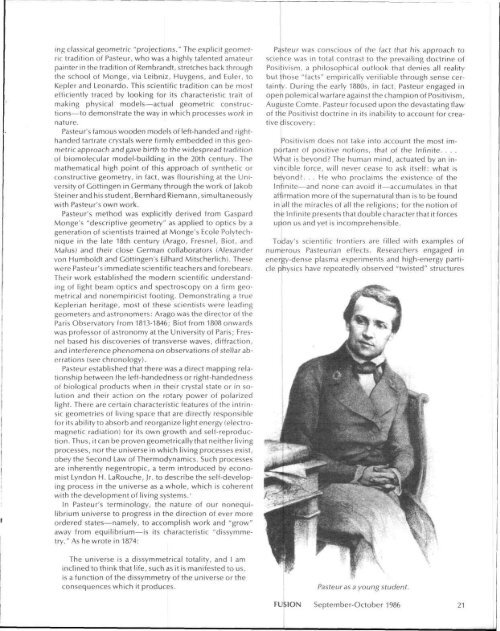

<strong>Pasteur</strong> as a young student.<br />

FUSION September-October 1986 21