Contents - Musée Maillol

Contents - Musée Maillol

Contents - Musée Maillol

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Contents</strong><br />

1. Press release 3<br />

2. Presentation of the exhibition by Stefano de Caro 4<br />

3. A tour of the exhibition through the objects presented 7<br />

4. «Love on the walls» by Antonio Varone 10<br />

5. Extracts from the catalogue 13<br />

« The matron in her house » by Marine Bretin-Chabrol 13<br />

« Water and its uses around the home » by Hélène Dessales 14<br />

« Gardens » by Annamaria Ciarallo 14<br />

« The discovery of Pompeii and its effects on European culture » by Cesare de<br />

Seta<br />

6. List of the objects on show 17<br />

7. Visual documents available for the media 27<br />

8. Useful information 33<br />

PRESS CONTACTS<br />

Agence Observatoire<br />

2 rue mouton duvernet - 75014 Paris<br />

Céline Echinard<br />

+33 (0)1 43 54 87 71<br />

celine@observatoire.fr<br />

www.observatoire.fr<br />

<strong>Musée</strong> <strong>Maillol</strong><br />

Claude Unger<br />

+33 (0)6 14 71 27 02<br />

cunger@museemaillol.com<br />

Elisabeth Apprédérisse<br />

+33 (0)1 42 22 57 25<br />

eapprederisse@museemaillol.com<br />

15<br />

2

1. Press release<br />

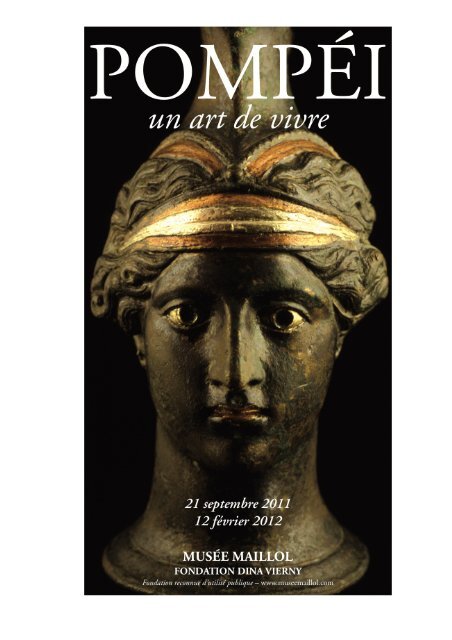

THE MUSÉE MAILLOL<br />

presents the exhibition<br />

Pompeii - A Way of Life<br />

From 21 September 2011 to 12 February 2012<br />

The <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>Maillol</strong> conceived this exhibition – under the guidance of the Italian Ministry for<br />

Cultural Heritage and Activity and of the Special Superintendence for the Archeological<br />

Heritage of Naples and Pompeii, and the museum’s artistic director, Patrizia Nitti, in<br />

accordance with the President of the Dina Vierny, Olivier Lorquin – to show the modernity of<br />

Roman civilisation, the bedrock and inevitable precursor of our Western culture.<br />

A domus pompeiana – a Pompeiian house – will be brought to life through its most famous<br />

and traditional rooms: the atrium, triclinium and culina, the peristyle around the garden, the<br />

balneum and venereum. Each room will be decorated with frescoes and objects, including<br />

200 works from Pompeii and other sites around Vesuvius.<br />

While there are numerous and often well preserved public monuments from the Roman<br />

Empire – theatres, amphitheatres, spas, temples – apart from the ones found buried by the<br />

eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD at Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae, private houses<br />

are rare and have never been found complete anywhere else. These houses and villas still<br />

fascinate us because of their state of preservation.<br />

Their infrastructure – running water, heating systems, sewers, use of green spaces, right<br />

down to the design of their everyday objects – seems spectacularly modern.<br />

The exhibition will invite visitors to walk around in this house as if it were their own, creating<br />

the illusion that they are guests of the owners, despite the 2,000 years that separate us from<br />

them.<br />

<strong>Musée</strong> <strong>Maillol</strong><br />

Olivier Lorquin, President<br />

Patrizia Nitti, Artistic Director<br />

Scientific Committee<br />

Teresa Elena Cinquantaquattro, Superintendant, Special Superintendence for the Archeological<br />

Heritage of Naples and Pomeii,<br />

Alain Pasquier, Honorary General Curator<br />

Exhibition Commission<br />

Valeria Sampaolo, Director of the Naples National Archeological Museum<br />

Antonio Varone, Excavations Director at Pompeii<br />

Stefano De Caro, Honorary Director General of Archeological Heritage, professor at the University of<br />

Federico II in Naples<br />

Design<br />

Hubert Le Gall<br />

3

2. Presentation of the exhibition<br />

by Stefano De Caro, Honorary Director General of Archeological Heritage, professor<br />

at the University of Federico II in Naples<br />

A civilisation’s fall often leads to its oblivion. From this point of view the Roman Empire is<br />

unusual to say the least. Thanks to the precious work of the copyists in mediaeval<br />

monasteries, a large number of written sources by historians, poets, rhetoricians, architects<br />

and lawyers have come down to us. We can thus reconstruct, almost year by year, the<br />

history, political life and conquests of Rome, that little village of shepherds on the Palatine Hill<br />

that became the capital of the Mediterranean world, the centre of an empire stretching<br />

westwards and eastwards from the Atlantic to the borders of Mesopotamia, and to the north<br />

and south from Hadrian’s Wall to the Sudan.<br />

However this written knowledge is mainly about public events: battles, victories, or about the<br />

principles of law and major public building works. The ancient sources give us relatively little<br />

information about the private lives of ordinary people in the cities of the Empire, and where<br />

they do, it is glimpsed between the lines of a life of Caesar or within the exaggerated<br />

adventures of a Trimalchio. And the records don’t give us much more. Even when they are<br />

about private events such as death, their nature is essentially public.<br />

To tell the truth, most of what we know of the daily life of the Ancient Romans, and what<br />

forms the basis of our image of this civilisation – the image in films like Gladiator or in the<br />

novels of Lindsey Davis – is owed to the excavations started more than two and a half<br />

centuries ago in the coastal towns of the Gulf of Naples that were buried by Vesuvius in 79<br />

AD after the terrible eruption that in a few short hours put an end to all life there. Very few<br />

other events in the history of humanity can be compared to the magnitude of such<br />

destruction – probably only the ocean tsunamis in Asia or the atomic bombs of Hiroshima<br />

and Nagasaki. Yet, as Goethe realised, such a terrible event was destined to become a<br />

source of joy for posterity. Each new archeological discovery revealed by the excavations<br />

made people realise that this crystallisation had resulted in outstanding historical evidence.<br />

Even today, in an age when archeology has made huge progress right across the expanse<br />

that was the Roman Empire, and now that we know so much more about so many ancient<br />

sites, Pompeii has kept its value as a landmark, both as a precise, datable moment and also<br />

as a point of cultural comparison with all the discoveries that are made in the field of Roman<br />

antiquity.<br />

At the moment of their destruction, Pompeii and Herculaneum were towns that already had<br />

several centuries of history behind them, just like most Italian cities of the time. Yet politically<br />

they weren’t particularly important. And it’s exactly that “ordinary” nature that is worth<br />

highlighting, for these two towns constituted a representative sample of Roman civilisation,<br />

far from the distortions that the status of capital inevitably gave to Rome.<br />

That is why, right from the first archeological discoveries in the middle of the 18 th century,<br />

attention was drawn to the numerous traces of daily life. In Rome, or in the ancient<br />

European cities of Roman origin, you could certainly see great monuments, amphitheatres,<br />

temples, aqueducts, even roads, or impressive tombs that had survived the collapse of the<br />

4

ancient world and lasted into the Middle Ages. But where were the houses? No one had ever<br />

seen one in its entirety; there might just be the odd room hidden here and there in some<br />

cave in a Roman hill. Even if such rooms were occasionally magnificently decorated with<br />

frescoes, there was no Ancient Roman house that could be studied from the point of view of<br />

surveying it to try to understand what the ancient sources meant when they spoke of<br />

atriums, peristyles and tablinums. The shock came first at Pompeii, for at Herculaneum they<br />

had already started to excavate the theatre, discovering a plethora of statues in marble and<br />

bronze. Visitors to those Pompeii houses were impressed of course by the abundance of<br />

painted decorations and mosaics, as well as by the variety of objects found there, but above<br />

all they were struck by the small size of the buildings. Goethe went as far as calling them<br />

“dolls’ houses”, which hardly fitted with the expected “magnificence of the Ancient Romans”,<br />

if the etchings of Piranesi were to be relied upon.<br />

That surprise was soon followed by enthusiasm. These houses revealed an extremely refined<br />

way of life. There had been running water in every household, thanks to a system of<br />

hydraulic pipework, and every house had its own garden. There was a vibrant cultural life,<br />

even at a domestic level, as could be inferred from reading the many pieces of graffiti.<br />

Foreign religions were accepted, even within local sanctuaries. The dissolute of course<br />

praised the liberal approach to sex, but it could also be observed that an unexpected<br />

number of citizens took part in local elections.<br />

The shock was particularly harsh for young European architects who came to acquire their<br />

“good taste” in the Roman Academies, and who were obliged to study antiquity by copying<br />

the great classical monuments and by adopting the principles of Vitruvius. The Pompeii<br />

houses became the new models that they had to follow. As well as the usual surveys, these<br />

architects created “restorations” that would bring back colour and life to the bare ruins that<br />

Herculaneum and Pompeii had become.<br />

What also changed was that any artist who wanted to paint a Roman interior could from now<br />

on only take his inspiration from a Pompeii house and from the huge collection of furniture<br />

that the King of Naples put on display first in Portici then in Naples itself. The paintings and<br />

mosaics that were discovered also inevitably became models, whether it was the works left<br />

in situ or those that had been taken away and displayed in royal collections. The Napoleonic<br />

Neo-Classicism of David gave way to the more intimist pictures of the Romantic painters<br />

who were moved by Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel The Last Days of Pompeii. In that book<br />

the house of the protagonist, Glaucus, was directly inspired by one that was lovingly<br />

reconstructed by the archeologist Désiré-Raoul Rochette. It’s impossible too not to mention<br />

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who had a very rich collection of photographs from Pompeii that he<br />

kept in his studio.<br />

Those who had the means even wanted to have their own “Pompeinum” made, starting with<br />

King Louis I of Bavaria at Aschaffenburg, built by Friedrich von Gärtner between 1840 and<br />

1848. In Paris, Prince Napoleon (1822-1891), son of Jérôme Bonaparte, commissioned a<br />

“Pompeian House” for his residence at 18 avenue Montaigne, Paris, from the architect<br />

Alfred-Nicolas Normand. A former member of the Academy of France in Rome who had<br />

made magnificent drawings at Pompeii, Normand built what was without doubt his<br />

masterpiece, a town house which has disappeared today but which was recorded for<br />

5

posterity by Gustave Boulanger in a famous painting. And what about the Villa Kérylos, built<br />

at Beaulieu-sur-Mer by Théodore Reinach, which mixed Greece and Pompeii, or even the<br />

majestic villa built more recently for John Paul Getty at Malibu, directly modelled on the Villa<br />

des Papyrus at Herculaneum?<br />

This rediscovered world was quickly peopled with inhabitants. First, of course, were the<br />

heroes of novels such as Arria Marcella, dreamed up by Théophile Gautier. Then came<br />

plaster casts of the victims of the eruption, recreated by Fiorelli, using his own technique.<br />

Finally it was Pompeii’s ghosts, such as the haunting Gradiva in a story by W. Jensen, the<br />

subject of a famous psychoanalytical study by Sigmund Freud.<br />

With time archeologists have learnt to carry out detailed excavations of the Pompeian house<br />

– you could simply say the Roman house – distinguishing between the different types of<br />

design, eras of construction and styles of decoration. They have learnt to differentiate found<br />

objects increasingly accurately between those made locally and those that had been<br />

imported. They have discovered how to distinguish between the different social classes of<br />

the population, even though it is very difficult to do so: besides the citizens, they had to<br />

count freemen, slaves, who left almost no traces even though there were many of them, and<br />

women. This kind of knowledge makes a visit to Pompeii, to Herculaneum or to the Naples<br />

Museum even more interesting because it takes us beyond the cliché too often promoted by<br />

mass tourism, which all too easily portrays Pompeii as the town of pleasure and death.<br />

At what is a difficult time for the conservation of these ancient cities, an exhibition at the<br />

<strong>Musée</strong> <strong>Maillol</strong> on such an important subject as the Pompei house aims to remind Europe of<br />

the debt of knowledge its culture owes to Herculaneum and Pompeii. As unique witnesses to<br />

the ancient world, these towns are quite rightly classed as UNESCO world heritage sites.<br />

The more so because they belong to our culture, thanks to the excavations that have been<br />

carried out in these past centuries and which have made them part of the archeological<br />

techniques and artistic taste that are now ours. The Pompeii house is therefore doubly<br />

revealing: both of what we were 2,000 years ago and what we have been for the last two<br />

and a half centuries.<br />

6

3. A tour of the exhibition through the objects presented<br />

by Valeria Sampaolo, Director of the Naples Archeological Museum<br />

Exhibitions are often dedicated to artists, or particular eras or techniques. This one looks at<br />

art and its history through an original prism, that of the Roman house. At the end of the<br />

republican era and at the beginning of the Roman Empire, the patrician house effectively<br />

became the best way to show one’s prestige and social rank. Things were certainly a bit<br />

more difficult in Rome itself, where laws limited the display of luxury, in memory of the strict<br />

founding fathers of the Urbs. So it was in the outlying towns where free rein was given to<br />

more sophisticated comforts, starting with the constuction of houses out of unusual<br />

materials, sometimes specially imported from distant lands. The law in Rome also applied to<br />

provincial towns but the farther away one was from the once modest city that had become<br />

the capital of a huge empire, the more freedom there was in this kind of choice. The eruption<br />

of Vesuvius in AD 79 left us an incredible “freeze-frame image” of that moment. At the<br />

bottom of an agricultural valley a town of no particular importance was frozen in an instant by<br />

the ash, which allowed it to travel through time. It was called Pompeii: the name has become<br />

mythical, but also as a place that bears unprecedented witness to the way of life of our<br />

distant ancestors almost 2,000 years ago.<br />

To create this exhibition we decided to draw on the main places that hold the essence of<br />

Pompeii’s memory – the archeological site itself, of course, and even more so the collections<br />

of artifacts, especially those of the Naples Archeological Museum, which I have the honour of<br />

directing. The idea of the exhibition was simple and effective: it was to recreate the<br />

experience of a visit that a passing stranger might have made to a wealthy home in Pomeii<br />

on an ordinary day. Let’s try to imagine what this experience would be like, to put ourselves<br />

in the place of the stranger.<br />

Before being presented to the master of the house, the visitor is still in the atrium. He looks<br />

at the inner walls decorated with pictures of gods or winged genies. The pond filled with<br />

rainwater sends dancing reflections across the frescoes. Next to it is a marble table and the<br />

opening of a well that gives access to an underground cistern. Further on there’s a sturdy<br />

safe in iron and bronze, then the “lararium” shrine, the chapel where there are small bronze<br />

statues of the household gods as well as other more important ones – certainly an Isis for<br />

one, because she protects those with maritime connections to Roman provinces in Africa<br />

and Egypt. It will put the visitor in mind of other auguries to be found throughout the house,<br />

probably including a fresco in the kitchen showing domestic gods who appear to dance as<br />

they hold aloft the ritual drinking horn overflowing with wine, close to great snakes that slither<br />

towards the small altar on which are spread realistic-looking sausages, meats and pigs’<br />

heads.<br />

You have to pass through a gallery, the tablinum, to get to private part of the house. Painted<br />

on the walls are landscapes showing cities spread out across several perspectives, starting<br />

7

with blind loggias that seem to appear like a trompe-l’oeil. Other scenes describe such and<br />

such adventure of the gods or ancient heroes, modernised and made popular by poets of<br />

the time. Here you can see the tools needed for writing and for doing accounts, such as a<br />

stylet, wax tablets and a roll of papyrus. Our visitor then goes past the cubicula, dimly-lit<br />

bedrooms and, next to the back entrance, he notices the venereum, a bedroom where<br />

slaves were prostituted (a source of income for the household), on the walls of which are<br />

pictures of lovers in positions that don’t need to be explained here.<br />

Our man waits for the master of the house in one of the large rooms that open on to the<br />

colonnade that surrounds the private garden. Walking across it, he stops for a moment to<br />

see if the peacock on the railing is real or if it’s part of the fresco on the back wall, behind<br />

bushes that actually are real. On the wall there’s also a niche decorated with mosaics, and a<br />

fountain, or rather a nymphaeum. The fantastic world of nymphs – who lived in waters and<br />

woods – is also evoked by the group of marble statues representing Pan and a satyr, as well<br />

as by the oscilla, these mobile discs featuring satyrs and Silenus. And finally let’s not forget<br />

the masks of marble and clay hanging between two columns of the peristyle, or the little<br />

statues of animals with jets of water coming out of them.<br />

At last we enter the triclinium, the dining room with beds in it, where they lie back to eat their<br />

meals. The bedheads are shaped like young satyrs, or heads of swans or mules. On the low<br />

brass tables there are finest ceramic plates with a reddish-orange sheen. Glass plates are<br />

more ordinary but lighter, too, in an infinite variety of colours, from blue to lemon yellow and<br />

iridescent green. In the Satyricon by Petronius, Trimalchio states that it’s better to eat and<br />

drink out of glass than metal because glass has no smell; he even preferred it to gold,<br />

though he did complain about its fragility, but then this mythical chef didn’t have to think<br />

about money…. Still in the dining room we can see bronze meat skewers and precious silver<br />

cups in ancient designs of unparalleled luxury. And then there are the little spoons with their<br />

pointed handles designed to remove shellfish and other crustaceans from their shells. There<br />

was plenty of technical progress in Pompeii, especially in the two appliances that could be<br />

used for either heating or cooling drinks, depending on whether you put in a piece of coal or<br />

snow – and in southern Italy it was more often the latter. As the evening begins to draw on,<br />

we see the lighting of beautiful bronze lanterns (the luxury version of clay ones), either<br />

perched high above the candelabras, hung from the trees or from some motionless youth,<br />

also made of bronze.<br />

Our visitor has other ways of observing the calibre of the people whose house he’s in: by<br />

looking at the jewellery of the mistress of the house; or even just from the frescoes. In this<br />

other triclinium, for example, the one showing Dionysis discovering Ariadne is so subtle that<br />

it must have been painted by craftsmen who’d come from Rome. Elsewhere you can even<br />

recognise the Emperor Nero in the guise of Orestes beside his cousin Pylades.<br />

So the stranger knows that he is in a fashionable house and that his hosts no longer need to<br />

go to the public baths to wash themselves, as they did not too long ago, because they have<br />

a private balneum where you only need to turn on the tap to get running water from lead<br />

8

pipes. The bronze bath-tub that had to be filled by hand has been replaced by one in<br />

marble. Everything needed for body care is in there: the after-bath scrapers to get rid of the<br />

creams used liberally for rubbing and massage, as well as bottles and vials of perfumed oils<br />

that were applied to the hair, clothes and on feet – sometimes during banquets.<br />

Food was important, of course, and then – like now – it was not so much the quantity that<br />

counted but the quality. That was linked to the provenance of the ingredients used, which<br />

could be deduced from the varying shapes of containers depending on whether they came<br />

from Africa, Greece or Gaul, and whether they were used for oil, wine or sauce. The way the<br />

table was laid was also important, as was the care and attention paid by the slaves to satisfy<br />

all the dinner guests. In his Satires, Horace gave us a memorable picture of the arrival of a<br />

huge plate on which were pieces of crane covered in salt, coated with meal and with the liver<br />

of a well-fed goose. That must lead to indigestion – and shortly to the end of our visit.<br />

The artifacts chosen to feature in the exhibition don’t all come from the same house of<br />

course. Some of them first came to light in the 18 th century, such as the two superb<br />

frescoes, even if they are incomplete, taken from the house of the lyre player. The beautiful<br />

photophore, on the other hand, comes from the house of Fabius Rufus, which was<br />

discovered only at the end of the 20 th century; as is the case with the house of Julius<br />

Polibus, where this magnificent bronze bowl was found. But at Pompeii there weren’t only<br />

houses that were stuffed with precious things. The longest painted frieze ever found was in a<br />

very bare home. In Paris we won’t have the whole work but just the part showing a small<br />

boat on the Nile, in which every detail celebrates life, from the still-life wicker baskets to the<br />

pins in the women’s bodices and the lantern in which the flame is protected by sheets of<br />

mica. It’s proof that in Pompeii the taste for a pleasant life and for fine detail was not just the<br />

preserve of the very rich.<br />

9

4. « Love on the walls »<br />

by Antonio Varone, Excavations Director at Pompeii<br />

In the middle of the 18 th century the excavations started on the Pompeii site. As the work<br />

advanced, an entire town was returning to the light of day, with its streets, monuments and<br />

houses – and, inside these, furniture, paintings and splendid mosaics. Besides material<br />

things, they were rediscovering the organisation and cultural way of life of a whole society.<br />

Imagine the surprise of the archeologists of the time at the discovery of numerous outsized<br />

phalluses, some even that had wings or animal features! They were all over the place: along<br />

the streets, on walls and floors, as well as outside certain shops. The were sculpted in lowrelief<br />

or in the round but they were found in paintings too, where seemingly at every street<br />

corner visitors to the ruins were stunned by the sight of men endowed with gigantic,<br />

monstrous penises.<br />

Then when houses were uncovered with painted frescoes showing erotic scenes in crude<br />

realism, Pompeii was immediately judged to be a town of perversion and luxury from a moral<br />

point of view, a new Sodom which must have deserved its divine punishment. These moral<br />

judgments meant that Pompeii artifacts showing erotic acts, or with even with a hint of the<br />

erotic about them, were very soon dispatched to the “secret cabinet” in the Naples Museum.<br />

Thus they tried to bury this far too explicit reality in an inaccessible place where it wouldn’t<br />

cause offence. At the same time the places where this kind of object and image had<br />

remained in situ were closed to the public almost until the present day. What was even more<br />

shocking than the images themselves was the explicit way in which they were in full view of<br />

everyone.<br />

If we want to have a full understanding of this phenomenon, first we have to place the town<br />

of Pompeii in its historical context. There was nothing unusual about it; it was a very ordinary<br />

town in the Roman world, close enough to Rome in this first century AD to be completely<br />

integrated in its social fabric. We also have to try to get rid of our preconceptions, the result<br />

of f 2,000 years of change in thought and religion. These are what influence our approach to<br />

the matter, both morally and socially, to a greater or lesser extent .<br />

We have to recognise that in a society that knew neither doubt nor sin nor prudishness nor<br />

the malice typical of out time, sex was experienced with much greater simplicity. Of course<br />

this spontaneity often showed itself in a crude way and eroticism looked completely different<br />

from what we are used to today.<br />

The Roman world didn’t need circumlocution or veils, physical or mental, to cover up human<br />

nudity. The rules about sex were mainly concerned with purely social aspects, not morality.<br />

They eagerly but apparently innocently pursued practices that today are considered as<br />

perversions, without ever thinking of them as such. The very concept of obscenity didn’t<br />

exist, no more than that of morbidity, even for acts and habits that unanimously offend our<br />

current sensitivities as being unacceptable violations.<br />

Above all, sex for the Romans was a positive phenomenon, a source of joy and life, a thing<br />

of magic. It even had a religious aspect that linked it to human destiny. The “physical” was<br />

the goddess of reproducing life whom the people of Pompeii worshipped as their protectress<br />

during the Samnite period. In the Roman era she quite naturally became identified with the<br />

goddess of love, Venus.<br />

That’s why the phallus was shown on the tombs of men and the uterus on those of women,<br />

to show respectively the genius and the luno of the dead, this supernatural germinating force<br />

10

that continues to exert its influence even after death. That is what makes life continue<br />

through new generations.<br />

From this point of view we can understand why there would be no shame in representing a<br />

phallus; it is not remotely an “obscene” image that should be removed from sight, not even<br />

from the sight of children. If it’s shown as being outsized that’s the better to summon its<br />

magical power that can ward off evil spirits and protect the house and workplace from the<br />

evil eye. This phallic god was Fascinus who, like Priapus, god of fertility in the garden, would<br />

punish with the power of his fleshy weapon anyone who tried to harm him.<br />

What innocent eye could disapprove of the image of this vital force offering protection and<br />

wealth at the house door? What guest could take offence on entering a home where wellbeing<br />

was guaranteed by this god who prevented evil from crossing the threshold? Such<br />

images don’t come from vice and there is nothing obscene about them. They are more the<br />

result of the age-old fear of dark forces and the desperate attempt to be protected against<br />

them. So the phallus fully belongs to the religious mystique of life. And it was in this religious<br />

place dedicated to life’s mysteries that young girls went through the initiation rites that<br />

marked their passage from adolescence to sexual maturity.<br />

Sex then is divine. So it’s quite natural that the joy and pain of sexuality were projected into<br />

the world of the gods, even if that transposition was both subtle and ambiguous. On the<br />

divine scale there was the whole range of passions, vices and virtues that go together with<br />

sex in love’s eternal game. The gods’ acts and the situations they experience are intimately<br />

linked to the inexplicable mysteries of sex. Venus, the goddess of love, thus has a major role:<br />

it’s she who captures the human soul and gives no mercy to whoever has the misfortune to<br />

be caught in her nets.<br />

The figure of Hermaphrodite with his mixed characteristics of male and female, is also bound<br />

up in sexual uncertainty. This god is treated with respectful silence. And if Hermaphrodite<br />

was often represented at the time as being between sleep and wakefulness it’s because we<br />

have to understand that this state is something close to a trance. As he combines in a single<br />

body the double nature of man and woman, Hermaphrodite has access to the saint of saints<br />

of Nature herself, he knows her mysteries and anticipates her choices. Didn’t the blind<br />

Teiresius, the most famous soothsayer of the classical world, experience the condition of<br />

being a man as well as being a woman?<br />

The respectful, meditative atmosphere that surrounds the personality of Hermaphrodite is<br />

occasionally contradicted by his sarcastic smile, evidence of another aspect often found in<br />

these erotic paintings: irony. This distancing aims to moderate the crude sexual nature of<br />

some pictures so as to make them more socially acceptable. It’s most often the case when a<br />

male figure in a Dionysian party – whether it’s Pan, a satyr or even Silenus – becomes<br />

infatuated with Hermaphrodite’s female curves, which he mistakes from behind for a female<br />

follower of Bacchus. Very quickly he changes his tune as he discovers with disgust that the<br />

lower belly of his designated victim reveals an object of desire that is not quite what he had in<br />

mind!<br />

If the Romans projected an ideal love on to the divine world, in their myths we find a more<br />

impulsive and guilty kind of love. For it’s there that we find indecent stories that would not<br />

have been thought acceptable in real life but they still excited the imagination. One of the<br />

subjects most often described is of a sexual attack by a satyr on a maenad: the subject of<br />

sexual violence by men, which cannot be justified or tolerated by any society, is thus<br />

transposed to a “neutral” setting. Some researchers believe that such violence is typical of<br />

the Ancient Roman world, where such standards of behaviour prevailed.<br />

11

It is this subject that is behind one of the inscriptions that will be shown in the exhibition, an<br />

incitement to a young girl who is furious at having been forcibly kissed to enjoy the pleasures<br />

of love: “Oh sensual young girl, you begrudge me my stolen kisses: I am certainly not the first<br />

one. Accept them and love! Prosperity to all who love.” That last phrase is a reference to a<br />

rather bawdy song found written more than once on the walls of Pompeii: “Prosperity to<br />

those who love, death to those who don’t know how to love; and death twice over to those<br />

who prevent love.”<br />

And it’s really this graffiti, scribbled on walls with a pointed stylet, that best brings back to us<br />

in the anonymous voices of Pompeii how much love was an integral part of the earthly<br />

condition of man at that time. It shows us the true face of a time when humanity could fully<br />

experience the spirituality that is part of the nature of love, in an intimate meeting of flesh and<br />

feeling.<br />

Emerging from this unknown chorus is the most authentic face of a society for whom love<br />

meant anguish, torment and jealousy for sure, but also sensuality, passion and serenity.<br />

Listen to those voices a bit more. The voice of a stranger who wants to go home to Rome to<br />

embrace his household gods but who is detained in Pompeii by an insurmountable obstacle,<br />

as we read on a wall: “We came here full of desire, but our desire to leave is even more<br />

intense; alas, this young girl won’t allow it.” The smile of a young girl, her eyes that demand<br />

to be gazed into, they all prevent him from turning for home. It’s desire, too, that leads<br />

another to write a delicate complaint, in which unattainable happiness is bound up with<br />

hope: “Happy are those who share the sleep of the night with you! Ah, if I was one of them I<br />

would be so much happier!” Finally, in another couplet, the exciting languor of desire comes<br />

across as a sophisticated and painful sensuality: “For a mere hour I would like to be the jewel<br />

in your ring, so that when you moisten it with your lips to mark your seal, I would be able to<br />

give you all the kisses that I have no right to lavish on you.”<br />

To exult in sex, just as to experience it, is a basic human need. When it’s not associated with<br />

any notion of sin it’s easy to indulge in such exultation. What the walls of Pompeii reveal is<br />

the maturity of a people who have been able to find a balance between sexual desire and<br />

moral behaviour.<br />

12

5. Extracts from the catalogue<br />

« The matron in her house »<br />

By Marine Bretin-Chabrol, master of conferences in Latin language and literature at the<br />

University of Lyons.<br />

In Roman society at the beginning of the Empire there wasn’t a unique and universal family<br />

model within which the feminine condition could be depicted. Women’s lives were<br />

determined as much by the social structures they belonged to within Roman society as by<br />

their sex. It depended on whether they were slaves, freemen or born free, their age, their<br />

place in a network of family and alliances, their social status (dignitas), meaning their place,<br />

through their father or husband, within a perhaps prestigious order (senatorial, equestrian,<br />

etc) and in an electoral class conferred by their fortune.<br />

To our modern eyes the matron who was a free woman, legitimately married, and from a<br />

privileged social rank seems a deceptively familiar figure. At the age of 12, but more often<br />

between 15 and 18, the young free-born girl puts on the orange marriage veil and goes<br />

through the rite of leaving her parents’ house to move to that of her new husband. By<br />

marrying, she becomes the wife of her husband (uxor), the mistress of her house (domina)<br />

and, in the eyes of society, a married woman and therefore respectable (matrona, or even<br />

materfamilias). Outside the house she now wears the stola, a long dress with sleeves, as<br />

evidence of her new status. She is allowed to practise the religious rites reserved for married<br />

women, such as those of Bona Dea, Pudicitia, Fortuna Muliebris or Juno Caprotina, and she<br />

receives gifts from her husband for the Matronalia festival.<br />

(…)<br />

At the heart of the house, the wife is not cloistered in special quarters. But she has to avoid<br />

disturbing her husband’s strictly masculine activities, such as the mornings when he receives<br />

clients in the atrium. Apart from the time she spends washing and dressing, helped by one or<br />

more servants, she spends the days in that same atrium, in the company of her children who<br />

will be playing or studying. From here she supervises the work of the domestic slaves, who<br />

could number as many as several dozen in the wealthiest households; she receives her own<br />

vassals (the former freed slaves of her father’s, for example) and runs her affairs. She invites<br />

her parents and friends, or her husband’s friends, in the reception areas of the house: the<br />

suites, peristyles or gardens. In the evening she attends dinners (cenae) and banquets<br />

(conuiuia) organised through her husband, if the invitation includes wives. She drinks, plays<br />

dice and goes to entertainments, but also watches over the serving of the meals.<br />

13

« Water, and its uses around the home »<br />

By Hélène Dessales, master of archaeological conferences, Ecole normale supérieure, Paris<br />

“You ask for hot water; I don’t have cold water yet.” This complaint by the poet Martial (Ep.<br />

8, 67, 7-8) gives us some idea of how the provision of water and its various uses were<br />

valued in a Roman home. Little evidence remains of those uses, making any restoration<br />

difficult. However, the exceptionally well-preserved vestiges found at Pompei at least provide<br />

a key to understanding the different levels of water provision, and the types of equipment<br />

involved, whether for providing communal services or those in individual homes. By following<br />

the trail of piping that is still visible at the site, or by the marks left behind, archaeological<br />

studies can now evaluate the role that water played in the home, and how that role was<br />

reflected in three main areas: the way in which the urban water network was organised, the<br />

link between water and hygiene, and the role of water in décor. In Pompeii, what remains of<br />

the city’s hydraulics therefore tells us about the lives of its residents, from their daily routines<br />

to their personal and cultural habits.<br />

« Gardens »<br />

Annamaria Ciarallo, Director of the Applied Sciences Laboratory of the Archeological<br />

Superintendence of Naples and Pompeii.<br />

Pompeii’s vegetable plots and gardens constitute an exceptional record. It’s the only<br />

evidence that has come down to us about the organisation of green spaces in a provincial<br />

town of the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago.<br />

Thanks to new research techniques, especially since 1970, we have been able to identify the<br />

plants that were cultivated in antiquity, which has allowed us to reconstruct former gardens.<br />

Like today’s cities, Pompeii wasn’t just made up of streets and buildings. Every house,<br />

whether it was rich or poor, had its own garden. There were also green spaces aimed at the<br />

general population: baths, gymnasiums and temples. Burial grounds were confined to the<br />

outskirts of the town.<br />

In these gardens, some of them very extensive, others no bigger than a pocket handkerchief,<br />

they grew plants that were used in everyday life, both to feed the family and to sell at the<br />

local market.<br />

Some crops, such as grapes, were particularly important for the town’s economy. Others<br />

were used in locally made products. Sweet-smelling plants were used to produce essences<br />

that were employed to make ointments and perfumes, while others went into making<br />

wreaths for religious offerings.<br />

The fertile soil allowed for intensive farming and several harvests a year. They specialised in<br />

vegetables that could be preserved in vinegar or brine so that they could be consumed<br />

throughout the year. They also grew a lot of hazelnuts, figs, apples, pears and grapes for the<br />

table that could be eaten either fresh or dried. Peaches and figs were conserved in honey.<br />

Even in pleasure gardens the most popular plants were medicinal ones for home use, as well<br />

as other plants used for domestic purposes.<br />

14

« The discovery of Pompeii and its effects on European culture »<br />

By Cesare de Seta, Professor of Art History at the Italian Institute of Human Sciences<br />

Florence-Naples<br />

In 1745, five years after excavations were halted at Herculaneum, causing intense debate<br />

right across Europe, the King of Naples, Charles de Bourbon, authorised the restarting of<br />

archeological investigations around the little town of Civita. The Spanish engineer Roque<br />

Joachim de Alcubierre had trenches dug to examine the bowels of the earth. It was the end<br />

of March and the beginning of April 1748 when a few painted murals were brought to light<br />

and quickly restored by the painter Carnat. Then there was a helmet, until, on April 19, they<br />

discovered the first body mummified by the lava, as well as a lot of coins. After that, the yield<br />

was ever greater, but it wasn’t until 1756 that the name of Pompeii first appeared in the<br />

excavation records. It became the plot of a veritable story within a story, involving scholars<br />

from the whole of Europe, but also artists whose job is was to send out pictures of what the<br />

whole world wanted to see: an ancient town that had been miraculously preserved.<br />

The discovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii was a huge event in the history of taste and<br />

culture in the Age of Enlightenment. It wasn’t just a connection with antiquity that was being<br />

renewed from top to bottom but it was also a moment when thought was restructured in one<br />

fell swoop. In this sense the shock was unprecedented. It can even be likened to the cultural<br />

revolution praised by the humanists at the beginning of the 15 th century. This too was a<br />

veritable Renaissance, in rationalist thought as well as in the arts. The philosopher<br />

Giambattista Vico used these archeological discoveries to suggest a new interpretation of<br />

classical antiquity, a real premise of historical modernity.<br />

The excavations of the town of Pompeii were conducted using a technique that many today<br />

would consider to be looting. Rather than a unitary reconstruction of the town environment,<br />

the emphasis was mainly on digging for archeological artifacts that were then taken away to<br />

the royal villas at Portici, which were turned into a temporary museum. “They were digging<br />

just to find treasures,” John Moore notes, adding regretfully, that “the curious are not allowed<br />

to write about them, still less to draw these antiquities”. It was a complaint that was also<br />

made several times by Johan Joachim Winckelmann, as well as by François Latapie.<br />

Drawn by the news from Naples, the residents of the Academy of France in Rome, together<br />

with many foreign artists, quickly added a relatively lengthy visit to Herculaneum and Pompeii<br />

to their travels. The drawings that they did manage to take away with them fed into the taste<br />

for things Greek with a Herculanean-Pompeian style that was to have lasting effects on the<br />

arts in the second half of the 18 th century, culminating in the empire style. Pompeii’s success<br />

helped to increase cultural exchanges between Paris and Naples, especially among<br />

intellectuals.<br />

Thus the site of Pompeii found an echo throughout Europe: the tomb of Mamia is a<br />

particularly significant example, as much for its unusual appearance as for the descriptions of<br />

it that Goethe wrote in his journal. The books of Saint-Non and the engravings by the<br />

Hackert brothers familiarised the whole of Europe with the marvels of Pompeii.<br />

15

English artists, just like their French colleagues, played a principal role in this rediscovery.<br />

Robert Adam, Robert Mylne and Nathaniel Dance left for Italy in 1754; Dance didn’t reach<br />

Pompeii until a decade later, accompanied by his brother George Dance Jr, who was to play<br />

a decisive role in the spread of English Neo-Classicism. These examples, despite their<br />

sometimes substantial differences, are persuasive proof of how, between 1740 and 1760,<br />

the first generation of “reinventors” of antiquity, homing in on Herculaneum, Pompeii and<br />

Paestum, formed a kind of fellowship that followed the same route and provoked the same<br />

enthusiasm. This class of people, full of rivalries, were desperate for new discoveries; they<br />

engaged in lively debate about the preeminence of Greek art over Roman; they collected<br />

archeological artifacts, studied them, made drawings of them and cultivated a new taste in<br />

many European countries. The forest of names that made up such a group is a veritable<br />

labyrinth of paths that converge and separate. They all remain in the shadow of two giants,<br />

however: Piranesi on one side and Winckelmann on the other – both completely different<br />

from one another.<br />

The Napoleonic era signalled a decisive step in the excavations at Pompeii. No longer was<br />

the work focused only on gathering archeological artifacts; now it was also about conserving<br />

the buildings. It wasn’t long before an entire town came out of the earth.<br />

16

6. List of the objects on show<br />

These objects belong to the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei<br />

Statue honoraire d'homme en<br />

toge<br />

marbre<br />

H. 190 ; base 76 cm<br />

Inv. 6231<br />

MANN<br />

Statue honoraire de femme<br />

drapée<br />

marbre<br />

H. 190 cm<br />

Inv. 6250<br />

MANN<br />

Bague-sceau<br />

bronze<br />

H. max. 3 ; L. 6,5 ; l. 2 cm<br />

Inv. 4748<br />

MANN<br />

Moulage des corps de deux<br />

jeunes filles, Casa del<br />

Criptoportico, reproduction<br />

plâtre<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

20 pièces de monnaie<br />

Or, argent et bronze<br />

MANN<br />

Encrier<br />

bronze et argent<br />

H. 5,8 ; diam. 5,2 cm<br />

S.N./436<br />

MANN<br />

Buste d'homme<br />

marbre<br />

H. 33 cm<br />

Inv. 55514 (ex 3015)<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

* MANN : Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli<br />

Statue honoraire d'homme en<br />

toge<br />

marbre<br />

H. 205 cm<br />

Inv. 6234<br />

MANN<br />

Maquette de la maison du<br />

"Poète tragique"<br />

bois<br />

H. 63 ; L. 95 ; l. 66 cm<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Clef<br />

bronze<br />

l. 8 cm<br />

Inv. 71406<br />

MANN<br />

Moulage de chien,<br />

reproduction<br />

plâtre<br />

H. 60 ; L. 60 ; l. 60 cm<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Tire-lire terre-cuite<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 15,2 ; diam. Inf. 6,4 cm<br />

MANN<br />

Quatre panneaux avec puttis<br />

musiciens<br />

fresque<br />

H. 30 ; L. 165 cm<br />

Inv. 9176<br />

MANN<br />

Fresque au génie ailé,<br />

fragment<br />

fresque<br />

H. 77 ; L. 67,5 cm<br />

Inv. 8830<br />

MANN<br />

Statue honoraire de femme<br />

drapée<br />

marbre<br />

H. 148 cm<br />

Inv. 6248<br />

MANN<br />

Médaillon avec villa à la mer,<br />

fresque (fragment)<br />

H. 25 ; L. 25 cm<br />

Inv. 9511<br />

MANN<br />

Serrure<br />

bronze<br />

Diam. 13,5 cm<br />

Inv. 122601<br />

MANN<br />

Enduit aux graffiti, fragment<br />

H. 20 ; L. 63 cm<br />

Inv. 20564<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Fresque aux instruments<br />

d'écriture, (instrumentum<br />

scriptorium)<br />

fresque<br />

H. 36 ; L. 31 cm<br />

Inv. 9822<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à suspension<br />

bronze<br />

H. 44 ; diam. 17,8 cm<br />

Inv. 43468<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Fresque à l'homme oriental<br />

assis<br />

fresque<br />

H. 97,5 ; L. 86 cm<br />

Inv. 9368<br />

MANN<br />

17

Fresque avec Dionysos<br />

trônant<br />

fresque<br />

H. 81 ; L. 67 cm<br />

Inv. 9546<br />

MANN<br />

Margelle de puits<br />

marbre<br />

H. 62 ; diam. base 51; diam.<br />

bord 47,5 cm<br />

Inv. 120175<br />

MANN<br />

Fresque avec Vénus et<br />

Cupidon<br />

fresque<br />

H. 51 ; L. 47 cm<br />

Inv. 8897<br />

MANN<br />

Lare dansant<br />

bronze<br />

H. 21,5 cm<br />

Inv. 113262<br />

Isis/Fortune<br />

Bronze<br />

H. 16,4 ; diam. base 5,4 cm<br />

Inv.5316<br />

MANN<br />

Petit autel<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 25,4 ; L. 21,9 ; l. 18 cm<br />

Inv. 11669<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Enduit aux graffiti, fragment,<br />

maison de Julius Polybius<br />

enduit/fresque<br />

H. 90 ; L. 82 cm<br />

Inv. ----<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Coffre-fort<br />

bois, fer et bronze<br />

H. 101 ; L. 58 ; l. 92 cm<br />

Inv. 73021<br />

MANN<br />

Tuile faîtière avec gouttière<br />

provenant de la maison de<br />

Julius Polybius<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 28 ; L. 86 ; l. 77 cm<br />

Inv. 27014<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Hercule<br />

bronze<br />

H. 14,8 ; base H. 5,2 ; L. 5,6<br />

cm<br />

Inv. 113260<br />

Mercure<br />

bronze<br />

H. 17,7 ; L. 10 cm<br />

Inv. 115554<br />

MANN<br />

Esculape<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 19,6 cm<br />

Inv. 6946<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Brûle parfum en forme de<br />

berceau<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 11; L. 13,6 ; l. 8,8 cm<br />

Inv. 10946<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Entonnoir<br />

bronze<br />

H. 20,5 ; diam. 12,9 cm<br />

Inv. 73849<br />

MANN<br />

Table (cartibulum), avec<br />

piètement en forme de griffon<br />

marbre<br />

H. 85 ; L. 141 ; l. 78 cm<br />

Inv. 40683<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Fresque de laraire (Terzigno)<br />

H. 210 ; L. 260 cm<br />

Inv. 86755<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Lare dansant, bronze<br />

bronze<br />

H. 21 cm<br />

Inv. 113261<br />

MANN<br />

Jupiter<br />

bronze<br />

H.18,5 ; diam. base 6,5 cm<br />

Inv. 111022<br />

Génie<br />

bronze<br />

H. 23 ; base H. 8 ; L. 8 cm<br />

Inv 133334<br />

MANN<br />

Brûle parfum au serpent<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 15,3 cm<br />

Inv. 121605<br />

MANN<br />

Moule à gâteau en forme de<br />

coquille Saint-Jacques<br />

bronze<br />

H. 9 ; diam. 20 cm<br />

Inv. 76235<br />

MANN<br />

18

Moule à gâteau en forme de<br />

coquille Saint-Jacques<br />

bronze<br />

H. 4 ; diam. 13,5 cm<br />

Inv. 76262<br />

MANN<br />

Poêle<br />

bronze<br />

L. 17,3 ; l. 49 cm<br />

Inv. 76599<br />

MANN<br />

Amphore crétoise à vin<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 70 ; diam. 29,5 cm<br />

Inv. 4782 B<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Amphore espagnole à huile<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 54,5 ; diam. 39,2 cm<br />

Inv. 52925<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Askos en forme de renard ou<br />

de chien de Malte<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 13 ; L. 16 ; l. 9,4 cm<br />

Inv.11911<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poids pour balance<br />

basalte<br />

H. 7,9 ; L. 11,1 cm<br />

Inv. 54848<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poids pour balance<br />

basalte<br />

H. 3,8 ; L. 4,1 cm<br />

Inv. 6888 B<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Moule à gâteau<br />

bronze<br />

L. 24 ; l. 20 cm<br />

Inv. 76456<br />

MANN<br />

Louche<br />

bronze<br />

l. 28,7 cm<br />

Inv. 77636<br />

MANN<br />

Amphore nord-africaine à huile<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 88 ; diam. 33,5 cm<br />

Inv. 58180<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Amphore pompéienne à huile,<br />

(dressel 2/4)<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 92,9 ; diam. 30 cm<br />

Inv. 25129<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Balance à plateau<br />

bronze<br />

H. 56,3 ; L. réglette 25,3 ;<br />

diam. plateau 13 cm<br />

Inv. 43469<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poids pour balance<br />

basalte<br />

H. 4,8 ; L. 6,6 cm<br />

Inv. 55813<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Trépied de cuisine<br />

fer<br />

H. 14; L. 27 cm<br />

Inv. 10539<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poêle rectangulaire<br />

bronze<br />

H. 18,4 ; L. 18,4 cm<br />

Inv. 76555<br />

MANN<br />

Pot à une anse<br />

Terre cuite à parois fines<br />

H. 10 ; diam. 8 cm<br />

Inv. 187627<br />

MANN<br />

Amphore espagnole à garum<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 91 ; diam. 29 cm<br />

Inv. 31161<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Askos en forme de coq<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 31,5 ; L. 34,5 cm<br />

Inv. 13350<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poids pour balance<br />

basalte<br />

H. 10 ; L. 14 cm<br />

Inv. 54847<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poids pour balance<br />

basalte<br />

H. 3,6 ; L. 5,2 cm<br />

Inv. 3355<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Gril<br />

fer<br />

H. 7,8 ; L. 21; l. totale 39 cm<br />

Inv. 41448<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

19

Récipient pour la cuisson<br />

(caccabus)<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 9 ; diam. 20 cm<br />

Inv. 25316<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Bouteille à garum<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 50 ; diam. 13 cm<br />

Inv. 81743<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Four portatif (clibanos)<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 43 ; diam. 45 cm<br />

Inv. 85204<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Panneau représentant<br />

Iphigénie en Tauride<br />

fresque<br />

H. 154 ; L. 163 cm<br />

Inv. 9111<br />

MANN<br />

Trois médaillons<br />

fresque<br />

H. 34 ; L. 90 cm<br />

Inv. 9129<br />

MANN<br />

Panneau avec panier de<br />

figues<br />

fresque<br />

H. 52,6 ; L. 75 ; P. 3 cm<br />

Inv. 20612<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Carreaux de pavement<br />

hexagonal<br />

Marbre coloré (jaune ancien)<br />

H. 11 ; côté 14 cm<br />

Inv. 20505<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Récipient pour la cuisson<br />

(caccabus)<br />

bronze<br />

H. 12 ; diam. 21,2 cm<br />

Inv. 55095<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Poêle rectangulaire<br />

bronze<br />

H. 5 ; diam. 26 cm<br />

Inv. 55705<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Situle<br />

bronze<br />

H. 33,4 ; diam. 37 cm<br />

Inv. 1115<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Panneau avec Dionysos et<br />

Ariane<br />

fresque<br />

H. 195 ; L. 166 cm<br />

Inv. 9286<br />

MANN<br />

Panneau avec nature morte :<br />

anguilles et rougets, fresque<br />

fresque<br />

MANN<br />

Panneau avec panier de fruits<br />

fresque<br />

H. 55 ; L. 35,8 ; P. 3,5 cm<br />

Inv. 20621<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Carreaux de pavement carré<br />

Marbre coloré (jaune ancien)<br />

Côté 26 cm<br />

Inv. 41365<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Poêle<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 7,1 ; diam. 26,3 ; l. 31 cm<br />

Inv. 56169<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Mosaïque avec bouteille à<br />

garum<br />

H. 73,8 ; L. 30,6 cm<br />

Inv. 15189<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Fresques du triclinium de<br />

Carmiano<br />

Divers panneaux : H. 264 ; L.<br />

max. 478 cm<br />

Inv. 63683-7<br />

Fouilles de Stabia<br />

Panneau avec Narcisse et<br />

Putti<br />

fresque<br />

H. 69,5 ; L. 68 cm<br />

in. 9385<br />

MANN<br />

Panneau avec nature morte<br />

aux pommes dans un pot en<br />

verre<br />

fresque<br />

H. 45 ; L. 45 cm<br />

Inv. 8610<br />

MANN<br />

Panneau avec trois natures<br />

mortes<br />

fresque<br />

H. 21,5 ; L. 97,5 cm<br />

Inv. 8628<br />

MANN<br />

Mosaïque avec motif de portail<br />

Inv. 11065<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

20

Médaillon avec Bacchus et<br />

Ménade<br />

fresque<br />

H. 45 ; L. 45 cm<br />

Inv. 9284<br />

MANN<br />

Tasse à deux anses<br />

argent<br />

H. 6,2 ; L. 15,5 cm<br />

Inv. 7484<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Louche<br />

argent<br />

H. 9 ; diam. 5 cm<br />

Inv. 25715<br />

MANN<br />

Cuillère<br />

argent<br />

l. 14,8 cm<br />

Inv. 25397<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à bec en forme de<br />

souris<br />

bronze<br />

H. 9,5 ; l. 21 cm<br />

Inv. 72172<br />

MANN<br />

Candélabre à quatre bras en<br />

forme d'arbre<br />

bronze<br />

H. 56,5 cm<br />

Inv. 72226<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à bec (soudée au<br />

support Inv. 6883)<br />

bronze<br />

H. 8; l. 14,5 cm<br />

Inv. 20306<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Olpé<br />

argent<br />

H. 15,5 ; diam. 7 cm<br />

Inv. 7478<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Tasse à deux anses<br />

argent<br />

H. 5,7 ; L. 12,4 cm<br />

Inv. 7487<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Soucoupe<br />

argent<br />

H. 2,5 ; diam. 10,2 cm<br />

Inv. 25354<br />

MANN<br />

Petite cuillère<br />

argent<br />

l. 14,5 cm<br />

Inv. 25604<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à bec avec anse en<br />

forme de tête de chien<br />

bronze<br />

H. 10 ; l. 14 cm<br />

Inv. 2225<br />

MANN<br />

Candélabre en forme de<br />

portail<br />

bronze<br />

H. 25,5 ; base H. 17,7 ; L.<br />

13,2 cm<br />

Inv. 21812<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Table à piètement avec putto<br />

chevauchant un dauphin<br />

bronze<br />

H. 107 ; base H. 80 ; L. 50<br />

cm<br />

Inv. 13371<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Patère<br />

argent<br />

H. 8 ; diam. 16,8; l. 29,5 cm<br />

Inv. 7481<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Coupe au motif de strigiles<br />

argent<br />

H. 6 ; diam. 9,5 cm<br />

Inv. 25291<br />

MANN<br />

Soucoupe<br />

argent<br />

H. 2 ; diam. 11 cm<br />

Inv. 25587<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à bec avec motif de<br />

palme<br />

bronze<br />

H. 9 ; l. 21 cm<br />

s.n.337<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à bec avec tête de<br />

nubien<br />

bronze<br />

H.5 ; L. 7,5 ; l. 12 cm<br />

Inv. 133320<br />

MANN<br />

Support de lampe (soudé à la<br />

lampe à bec Inv. 20306)<br />

bronze<br />

H. 131 cm<br />

Inv. 6883<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Table pliante tripode<br />

bronze<br />

H. 110 cm<br />

Inv. 73951<br />

MANN<br />

21

Petite table<br />

bois et bronze<br />

H. 66 ; L. 58 cm<br />

Inv. 3303<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Tête de lit (fulcrum) à tête de<br />

cygne<br />

bronze<br />

H. 21 ; L. 32 cm<br />

Inv. 13115<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Table avec plan en mosaïque<br />

et pieds en marbre en forme<br />

de pattes de lion<br />

plateau diam. 112 ; pieds H.<br />

89 cm<br />

s.n.<br />

MANN<br />

Satyre dansant<br />

bronze<br />

H. 8,3 cm<br />

Inv. 27733<br />

MANN<br />

Assiette à pied<br />

terre sigillée<br />

H. 5 ; diam. 16,5 cm<br />

Inv. 16352<br />

MANN<br />

Calice au couple d'amoureux<br />

céramique d'Arezzo<br />

H. 13,1 ; diam. 15,7 cm<br />

Inv. 20568<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Cratère avec figures<br />

mythologiques de héros<br />

bronze repoussé<br />

H. 62,5 ; diam. 35,5 cm<br />

Inv. 45180<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Tabouret<br />

bronze<br />

H. 28,8 ; L. 25 cm<br />

Inv. 3753<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Pied de lit<br />

bronze<br />

H. 30 cm<br />

Inv. 21757<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Statue d'éphèbe soutien de<br />

table<br />

bronze<br />

H. 137 cm<br />

Inv.13112<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Satyre ityphallique<br />

s'aspergeant d'eau<br />

bronze<br />

H. 9,2 cm<br />

s.n.<br />

MANN<br />

Coupe provenant du sud de la<br />

Gaule<br />

terre sigillée<br />

H. 6,5 ; diam. 14 cm<br />

Inv. 112915<br />

MANN<br />

Rhyton<br />

céramique à parois fines<br />

H. 16 ; L. 7,1 ; l. 15,5 cm<br />

Inv. 11435<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Braséro<br />

bronze<br />

H. 96 ; diam. 44 cm<br />

Inv. 6798<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Tête de lit (fulcrum) à tête de<br />

mulet et putto<br />

bronze<br />

H. 21 ; L. 32 cm<br />

Inv. 13114<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Applique de lit en forme de<br />

petit satyre<br />

bronze<br />

H. 11,5 ; L. 7,5 cm<br />

Inv. 5295<br />

MANN<br />

Marchand ambulant<br />

bronze<br />

H. 26 ; L. 11 cm<br />

Inv.143761<br />

MANN<br />

Carafe avec anse<br />

terre sigillée<br />

H. 20 cm<br />

Inv. 16191<br />

MANN<br />

Coupe provenant du sud de la<br />

Gaule<br />

terre sigillée<br />

H. 11 ; diam. 25 cm<br />

Inv. 116995<br />

MANN<br />

Pot à masque<br />

anthropomorphe<br />

Terre cuite à parois fines<br />

H.11 ; diam. 9 cm<br />

Inv. 123<br />

MANN<br />

Récipient pour chauffer les<br />

liquides, dit "samovar"<br />

bronze<br />

H. 46 cm<br />

Inv. 73880<br />

MANN<br />

22

Situle à marqueterie de métal<br />

au nom de Cornelia Chelidon<br />

bronze<br />

H. 44 ; diam. 32 cm<br />

Inv. 68854<br />

MANN<br />

Cruche<br />

bronze<br />

H. 26 ; diam. 18 cm<br />

Inv. 1149<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Œnochoé avec anse décorée<br />

bronze<br />

H. 32,5 ; diam. 19,5 cm<br />

Inv. 4685<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Écumoir<br />

bronze<br />

H. 10,5 ; l. 34 cm<br />

Inv. 77602<br />

MANN<br />

Petite assiette<br />

verre<br />

H. 1,7 ; diam. 11,8 cm<br />

Inv. 12835 A<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Coupe panachée<br />

verre bleu<br />

H. 6,2 cm<br />

Inv. 13028<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Coupe<br />

verre vert<br />

H. 7,3 ; diam. 13,1 cm<br />

Inv. 11417<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Situle à anse avec réchaud<br />

bronze<br />

H. 24 cm<br />

Inv. 184985<br />

MANN<br />

Patère<br />

bronze<br />

H. 4,6 ; diam. 19,9 ; l. 31,3<br />

cm<br />

Inv. 11465<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Œnochoé avec anse en forme<br />

de satyre<br />

bronze<br />

H. 19 cm<br />

Inv. 335<br />

MANN<br />

Œnochoé<br />

verre bleu<br />

H. 11 ; diam. 9 cm<br />

Inv. 7520<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Petite assiette<br />

verre<br />

H. 2,2 ; diam. 12,5 cm<br />

Inv. 12835 C<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Verre<br />

verre soufflé en moule<br />

H.12 ; diam. 7 cm<br />

Inv. 129387<br />

MANN<br />

Fresque avec Vénus<br />

fresque<br />

H. 24 ; L. 30 cm<br />

Inv. 9181<br />

MANN<br />

Œnochoé à tête de femme<br />

bronze<br />

H. 14 cm<br />

Inv. E2541<br />

Fouilles de Herculanum<br />

Bassine<br />

bronze<br />

H. 11 ; diam. 34,4 cm<br />

Inv. 12097<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Vase à panier<br />

bronze<br />

H. 11,5 ; l. 35,5 cm<br />

Inv. 68775<br />

MANN<br />

Carafe<br />

verre<br />

H. 14,5 ; diam. 12,5 cm<br />

Inv. 12491<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Coupe côtelée<br />

verre<br />

H. 4,7 ; diam. 15,6 cm<br />

Inv. 10631<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Kalathos avec une anse<br />

verre bleu sombre<br />

MANN<br />

Fresque de l'amour<br />

malheureux<br />

H. 36 ; L. 43 cm<br />

Inv. 9378<br />

MANN<br />

23

Satyre et ménade<br />

fresque<br />

H. 46 ; L. 58 cm<br />

Inv. 27688<br />

MANN<br />

Phallus<br />

bronze<br />

l. 5 cm<br />

Inv. 27765<br />

MANN<br />

Lampe à bec à scène érotique<br />

Terre cuite<br />

diam. 11 cm<br />

Fiorelli 198<br />

MANN<br />

Fontaine<br />

mosaïque<br />

H. 240 ; L. 200 ; P. 177 cm<br />

Inv. 40689 a-g<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Dionysos à la peau de lépoard<br />

bronze<br />

H. 68 ; diam. base 26 cm<br />

Inv. E2292<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Enfant<br />

marbre<br />

H. 56 cm<br />

Inv. 53508<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Hermaphrodite<br />

marbre<br />

H. 24 ; L. 75 ; l. 38 cm<br />

Inv. 3021<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Satyre et ménade<br />

fresque<br />

H. 63,5 ; L. 57,5 cm<br />

Inv. 27691<br />

MANN<br />

Tintinnabulum avec nain<br />

ityphallique et lampe à bec<br />

bronze<br />

Personnage H. 16 cm ; lampe<br />

H. 4 ; l. 17,5 cm<br />

Inv. 1098<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de Boscoreale)<br />

Fresque avec scène de jardin<br />

fresque<br />

H. 115 ; L. 107 cm<br />

Inv. 8760<br />

MANN<br />

Table avec piètement au<br />

groupe sculpté, Silène et<br />

Dionysos enfant<br />

marbre<br />

H. 104 cm<br />

Inv. 1109<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Enfant au dauphin<br />

marbre<br />

H. 40,4 ; L. 35,3 ; P. 24,5 cm<br />

Inv. 41462<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Enfant<br />

marbre<br />

H. 56 cm<br />

Inv. 53509<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Pittaque de Mytilène<br />

Terre cuite<br />

H. 63 ; L. 29,5 ; l. 36,5 cm<br />

Inv. 20595<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Barque en forme de phallus<br />

avec Pygmées<br />

fresque<br />

H. 78 ; L. 209 cm<br />

Inv. 41654<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Phallus ailé avec quatre<br />

grelots<br />

bronze<br />

l. 16 cm<br />

s.n.<br />

MANN<br />

Fresque avec scène de jardin<br />

fresque<br />

H. 120 ; L. 75 cm<br />

Inv. 9719<br />

MANN<br />

Cratère à volutes, décoration<br />

de jardin<br />

marbre<br />

H. 86 cm<br />

Inv. 6779<br />

MANN<br />

Priape ityphallique<br />

marbre<br />

H. 99 cm<br />

Inv. 87265<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Pan et satyre<br />

marbre<br />

H. 55 cm<br />

6340<br />

MANN<br />

Oscillum<br />

marbre<br />

Diam. 29 cm<br />

Inv. 6641<br />

MANN<br />

24

Oscillum avec Achille et Troïlos<br />

Terre cuite<br />

Diam. 12,4 cm<br />

Inv. 11097<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Tortue<br />

marbre<br />

H. 12 cm<br />

Inv. 120043<br />

MANN<br />

Bassin sur pied à colonne<br />

cannelée<br />

marbre<br />

H. 95 ; L. 45 cm<br />

Inv. 126203<br />

MANN<br />

Aryballe<br />

bronze<br />

H. 9,5 cm<br />

Inv. 69970<br />

MANN<br />

Collier<br />

or et émeraude<br />

l. 39 cm<br />

Inv. 24607<br />

MANN<br />

Bague<br />

or et émeraude<br />

Diam. 2,5 cm<br />

Inv. 110908<br />

MANN<br />

Bracelet au serpent<br />

or<br />

Diam. 6,5 ; P. 0,3 cm<br />

Inv. 24897<br />

MANN<br />

Biche couchée<br />

marbre<br />

H. 24 ; L. 24,4 ; l. 41,9 cm<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Dauphin<br />

marbre<br />

H. 19 cm<br />

Inv. 120051<br />

MANN<br />

Baignoire<br />

bronze<br />

H. 44 ; L. max 63 ; l. 160 cm<br />

Inv. 73007<br />

MANN<br />

Miroir avec manche en forme<br />

de glaive d'Hercule<br />

bronze<br />

Diam. 15 ; l. 24 cm<br />

Inv. 111123<br />

MANN<br />

Collier<br />

or<br />

l. 250 cm<br />

Inv. 25260<br />

MANN<br />

Bague ornée d'une intaille<br />

or et corniole<br />

Diam. 2,5 cm<br />

Inv. 112865<br />

MANN<br />

Paire de boucles d'oreille<br />

or et pâte d'émeraude<br />

l. 3 cm<br />

Inv. 110914<br />

MANN<br />

Grenouille<br />

marbre<br />

H. 18 cm<br />

Inv. 120042<br />

MANN<br />

Bassin avec support en forme<br />

de vase tripode<br />

marbre<br />

H. 134 ; diam. 102 cm<br />

Inv. 6866<br />

MANN<br />

Strigile<br />

bronze et argent<br />

l. 22 cm<br />

Inv. 69994<br />

MANN<br />

Collier<br />

or et émeraude<br />

l. 32 cm<br />

Inv. 111116<br />

MANN<br />

Bracelet<br />

or<br />

l. 24 cm<br />

Inv. 110919<br />

MANN<br />

Bague au serpent<br />

or<br />

Diam. 2 cm<br />

Inv. 110913<br />

MANN<br />

Paire de boucles d'oreilles<br />

or<br />

l. 2,8 cm<br />

Inv. 111117<br />

MANN<br />

25

Épingle à cheveux<br />

os<br />

l. 12 cm<br />

Inv. 119428<br />

MANN<br />

Petite carafe<br />

verre<br />

H. 13,8 ; diam. 11 cm<br />

Inv. 6875<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Fiole à onguent<br />

verre<br />

H. 8,3 cm<br />

Inv. 115060<br />

MANN<br />

Petit flacon carré<br />

verre bleu clair<br />

H. 20 ; L. 9 cm<br />

Inv. 13011<br />

MANN<br />

Rhyton<br />

verre<br />

l. 21,2 cm<br />

Inv. 12493<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

(Antiquarium de di Boscoreale)<br />

Fiole à onguent<br />

verre<br />

H. 8,3 cm<br />

Inv. 115081<br />

MANN<br />

Bouteille<br />

verre<br />

H. 22,5 ; diam. 9,5 cm<br />

Inv. 4722<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

Fiole à onguent<br />

verre<br />

H. 9 cm<br />

Inv. 115148<br />

MANN<br />

Olpé avec une anse<br />

verre bleu clair<br />

H. 9 ; diam. 9 cm<br />

Inv. 23492<br />

MANN<br />

26

7. Visual documents available for the media<br />

Table (cartibulum), avec piètement en forme de griffon<br />

marbre<br />

H. 85 ; L. 141 ; l. 78 cm<br />

Inv. 40683<br />

Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei<br />

Fouilles de Pompei (Antiquarium Boscoreale)<br />

© Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei / Photo Pio Foglia<br />

Élégante pièce du mobilier, typique de l’atrium<br />

Coffre-fort<br />

bois, fer et bronze<br />

H. 101 ; L. 58 ; l. 92 cm<br />

Inv. 73021<br />

Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei<br />

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli<br />

© Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei / Photo Archivio dell'Arte - Luciano Pedicini/fotografo<br />

Coffre-fort (arca) en bois, revêtu de bandeaux de fer à décors en<br />

bronze, élément typique de l’atrium.<br />

Braséro<br />

bronze<br />

H. 96 ; diam. 44 cm<br />

inv. 6798<br />

Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei<br />

Fouilles de Pompéi<br />

© Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e<br />

Pompei / Photo Pio Foglia<br />

Les Romains ont créé toute une gamme d’appareils richement<br />

décorés, généralement en bronze, pour la production de l’eau chaude<br />

à utiliser durant les banquets du triclinium. Le cylindre évidé de celui-ci<br />