Total Time: 63:37 - Chelsea Rialto Studios

Total Time: 63:37 - Chelsea Rialto Studios

Total Time: 63:37 - Chelsea Rialto Studios

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

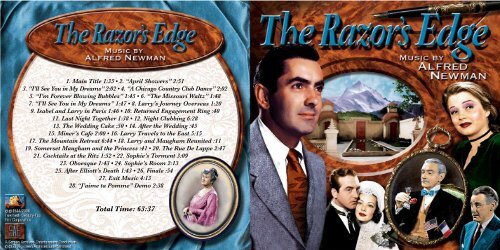

1. Main Title 1:35 • 2. “April Showers” 2:51<br />

3. “I’ll See You in My Dreams” 2:02 • 4. “A Chicago Country Club Dance” 2:02<br />

5. “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” 1:45 • 6. “The Missouri Waltz” 1:48<br />

7. “I’ll See You in My Dreams” 1:47 • 8. Larry’s Journey Overseas 1:20<br />

9. Isabel and Larry in Paris 1:46 • 10. Returned Engagement Ring :40<br />

11. Last Night Together 1:38 • 12. Night Clubbing 6:28<br />

13. The Wedding Cake :50 • 14. After the Wedding :45<br />

15. Miner’s Cafe 2:00 • 16. Larry Travels to the East 5:15<br />

17. The Mountain Retreat 6:44 • 18. Larry and Maugham Reunited :11<br />

19. Somerset Maugham and the Princess :41 • 20. The Rue De Lappe 2:47<br />

21. Cocktails at the Ritz 1:52 • 22. Sophie’s Torment 3:09<br />

23. Oboesque 1:43 • 24. Sophie’s Room 2:13<br />

25. After Elliott’s Death 1:43 • 26. Finale :54<br />

27. Exit Music 4:13<br />

28. “J’aime ta Pomme” Demo 2:38<br />

<strong>Total</strong> <strong>Time</strong>: <strong>63</strong>:<strong>37</strong>

n June 1944, Darryl F. Zanuck, 20 th Century-Fox’s<br />

studio head, was contemplating<br />

making a big decision. In a memo to key<br />

members of his staff he said:<br />

This is my analyzation of The Razor’s<br />

Edge [novel] by Somerset Maugham.<br />

Despite the fact that to date no producer<br />

on the lot has shown any great enthusiasm<br />

for this story as a motion picture and<br />

despite the fact that no other studio has<br />

purchased it, I am inclined to believe that<br />

we should buy it.<br />

The book was published in May, and it<br />

immediately went on the best-seller list. . . .<br />

There must be a reason why the<br />

American public at this moment is read-<br />

ing this book more than any other book.<br />

The answer, I think, is simple: Millions of<br />

people today are searching for content-<br />

ment and peace in the same manner that<br />

Larry searches in the book.<br />

The invasion of northern Europe had just<br />

taken place on June 6. With the Allies closing<br />

in on Germany from all sides, confidence<br />

rose that the end of World War II was in sight.<br />

And indeed it was. In 1945 the war ended and<br />

millions of military personnel were returning<br />

home to resume civilian life. But many,<br />

because of their experiences in the war, were<br />

unsettled. They realized that their values were<br />

in some ways changing. More than a few<br />

questioned the materialistic mode of living and<br />

were looking for a meaning of existence.<br />

In Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge, Larry<br />

Darrell near the end of World War I is saved<br />

from death by a comrade who gives up his life<br />

in the effort. Larry feels that his life has been<br />

spared for some particular purpose and wanders<br />

about the world in search of philosophical<br />

and/or spiritual guidance, leaving the woman<br />

he loves and material advantages. In India,<br />

he eventually achieves insight, tranquility,<br />

and “goodness of soul.” Larry, at the end, has<br />

found himself, and in helping himself he can<br />

help others.<br />

But as Zanuck said in a memo of December<br />

6, 1945: “Larry is not carrying any great message,<br />

nor is he looking to reform the world;<br />

he is looking only for the answer to his own<br />

quest for serenity and the key to his own future<br />

happiness. . . . This, to me, is the theme of Mr.<br />

Maugham’s book, and the reason it has been<br />

such a tremendously big seller. It is a problem<br />

which today is close to twelve million Americans.<br />

It is a picture of faith and hope.”<br />

Somerset Maugham in a September 1945<br />

interview said: “I’ve had hundreds – actually<br />

hundreds – of letters from soldiers at the front,<br />

telling me how well they understood Larry<br />

after their experiences. . . . Some of them have<br />

said they will try to live that way in the years<br />

ahead, if their lives are spared. You see, men at<br />

war are either desperately busy or have a good<br />

deal of idle time on their hands, so many of<br />

these letters run to twenty pages or more.”<br />

Above left: Director Edmund Goulding studies the mountain top retreat set on stage at Fox.

Religious novels (and films) were extraordinarily<br />

popular during World War II – The<br />

Keys of the Kingdom, The Song of Bernadette,<br />

The Robe, The Apostle, etc. They dealt with<br />

Christianity whereas The Razor’s Edge was<br />

the only one that featured a Hindu philosophy.<br />

The title of The Razor’s Edge came from the<br />

Katha-Upanishad: “The sharp edge of a razor<br />

is difficult to pass over; thus the wise say the<br />

path to Salvation is hard.”<br />

W. Somerset Maugham had been writing<br />

novels, plays, and short stories for decades<br />

prior to The Razor’s Edge. His first novel, Liza<br />

of Lambeth, was published in 1897. A 1915<br />

novel, Of Human Bondage, was made into<br />

a feature picture three times. The Moon and<br />

Sixpence (1919), based on the life of Gauguin,<br />

was filmed in 1942. Both Maugham’s The<br />

Letter and Rain (Sadie Thompson) were first<br />

published as short stories, reworked as plays<br />

by Maugham, and then produced as feature<br />

pictures. But The Razor’s Edge was his major<br />

“best-seller” novel.<br />

Zanuck purchased the screen rights in late<br />

1944 and assigned long-time Fox scenarist<br />

Lamar Trotti to work on the adaptation<br />

and script. Trotti’s previous credits include<br />

Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938), Drums<br />

Along the Mohawk (1939) Young Mr. Lincoln<br />

(1939), Man Hunt (1941), The Ox-Bow Incident<br />

(1943), and the recently completed personal<br />

production of Zanuck’s for Fox, Wilson<br />

(1945). The Razor’s Edge became Zanuck’s<br />

next personal production, meaning that in addition<br />

to overall supervision of the entire<br />

Edmund Goulding discussing “The Razor’s Edge”<br />

with Tyrone Power.<br />

Fox product, he would usually once a year<br />

or so select a property to which he would<br />

devote a considerable amount of time on a<br />

daily basis during the script’s evolution, preproduction,<br />

filming, and post-production.<br />

In May, 1945, George Cukor, not a Fox<br />

staff director but primarily with MGM<br />

at the time, was set to direct The Razor’s<br />

Edge. Cukor was unhappy with the script<br />

development and suggested to Zanuck that<br />

the studio ascertain whether Maugham himself<br />

would be interested in working on the<br />

script. Although Zanuck apparently thought<br />

it highly unlikely that Maugham would accept<br />

and/or that he would demand too much<br />

money, the author sent Zanuck a telegram<br />

saying that he would work on the screenplay<br />

for no pay whatsoever; surely a unique attitude.<br />

Maugham then spent June and July,<br />

1945, as George Cukor’s houseguest while<br />

working on his version of the script.<br />

Maugham had no experience writing<br />

screenplays. His first draft of July 20, 1945,<br />

was labeled “Story in Dialogue by W. Somerset<br />

Maugham.” The author’s preface stated<br />

that “The following is not to be looked upon<br />

as a script and will be incomprehensible<br />

unless it is read in conjunction with Lamar<br />

Trotti’s. It should be looked upon only as a<br />

story in dialogue. . . ”<br />

Then five days later he submitted his<br />

“Revised Final.” The following “Author’s<br />

Note” at the front of the script surely was<br />

composed at least in part with tongue-incheek.<br />

Maugham, of course, had been

involved over the years in many theatrical ventures<br />

of his plays.<br />

Please note that this is on the whole a<br />

comedy and should be played lightly by<br />

everyone except in the definitely serious<br />

passages. The actors should take up one<br />

anotherʼs cues as smartly as possible and<br />

thereʼs no harm if they cut in on one<br />

another as people do in ordinary life. Iʼm<br />

all against pauses and<br />

silences. If the actors<br />

can’t give significance<br />

to their lines without<br />

these they’re not<br />

worth their salaries.<br />

The lines are written<br />

to be spoken and they<br />

have all the significance<br />

needed if they are<br />

spoken with intelligence<br />

and feeling. The director<br />

is respectfully reminded<br />

that the action should<br />

accompany and illus-<br />

trate the dialogue. Speed! Speed! Speed!<br />

Zanuck wanted in some way to pay for<br />

Maugham’s services. Cukor suggested a painting<br />

to be chosen by Maugham with the cost<br />

stipulated by Zanuck not to exceed $15,000. A<br />

Matisse was selected.<br />

“I’m sure I derived more pleasure from<br />

that work of art than Mr. Zanuck did from my<br />

scenario on The Razor’s Edge,” Maugham told<br />

author Wilmon Menard in the early 1960s.<br />

“You see, he didn’t use a single line of my<br />

script in the final production. . . . I think Mr.<br />

Trotti made twelve versions before Mr. Zanuck<br />

approved of one. . . . They took a lot of liberties<br />

with my original novel in the final shooting<br />

script.”<br />

During the particularly long gestation period<br />

from purchase of the screen rights to the start<br />

of filming, several potential<br />

casting names for the key<br />

roles were bandied about<br />

and in some cases tested.<br />

Olivia de Havilland’s name<br />

pops up in newspaper columns<br />

more than any other<br />

over the months for the role<br />

of Isabel, Larry’s love who<br />

was put on “hold” while<br />

he traveled hither and yon<br />

in search of philosophical<br />

insights. Jennifer Jones had<br />

been sought, but producer<br />

David O. Selznick, who<br />

held her contract (although she owed Fox commitments),<br />

turned down the opportunity. Joan<br />

Fontaine, Olivia de Havilland’s sister, was<br />

also mentioned as a possibility for Isabel, as<br />

was Katharine Hepburn, Maureen O’Hara and<br />

Merle Oberon. For the role of Sophie, whose<br />

life was wrecked by tragedy, the possibilities<br />

included Fox contract player Nancy Guild, and<br />

young Angela Lansbury, who had made her<br />

American film debut in Gaslight (1944).<br />

In Anne Baxter’s 1976 autobiography,<br />

Intermission, she says that ex-child actress<br />

Bonita Granville was about to be cast when<br />

Baxter, under contract to Fox, asked to be<br />

tested. At the eleventh hour Baxter was set<br />

to play the drunken, opium-addicted, and<br />

degraded Sophie – certainly a change of pace<br />

for her.<br />

The Production Code Administration, the<br />

film industry’s self-regulatory<br />

body, after reading the<br />

submitted script, asked that<br />

references to heavy drinking<br />

be removed. Zanuck<br />

personally responded in<br />

a letter: “It is absurd to<br />

eliminate drinking from<br />

this picture as it would<br />

be to eliminate drinking<br />

from The Lost Weekend. .<br />

. . Alcoholism is the basic<br />

foundation of our plot. . . ”<br />

The drinking stayed.<br />

In August, 1945 it was<br />

announced that Alexander Knox would portray<br />

author Somerset Maugham, who in the<br />

novel is the observer-narrator. Knox had the<br />

leading role of President Woodrow Wilson in<br />

Zanuck’s 1944 personal production for Fox<br />

– Wilson. However, once again at the eleventh<br />

hour Herbert Marshall, who had portrayed the<br />

Maugham-like character in the 1942 film version<br />

of Maugham’s novel The Moon and Six-<br />

pence, took over the role. Thomas F. Brady in<br />

a July 28, 1946 New York <strong>Time</strong>s article stated<br />

that Maugham “did insist. . . that Herbert<br />

Marshall be engaged to play the raconteur of<br />

the [Razor’s Edge] tale.”<br />

In the one instance of sticking with the<br />

original casting announcement, Clifton<br />

Webb portrayed the snobbish socialite Elliott<br />

Templeton. Under contract to Fox since his<br />

impressive performance as Waldo Lydecker<br />

in the studio’s 1944 hit,<br />

Laura, Webb was an ideal<br />

choice.<br />

Britisher Philip Merivale<br />

was cast as the holy<br />

man in India that Larry travels<br />

to for guidance. But he<br />

died seventeen days before<br />

filming began and Britisher<br />

Cecil Humphreys replaced<br />

him.<br />

So what about Larry, the<br />

male lead? No preliminary<br />

announcements were made<br />

but since World War II ended<br />

in September, 1945, Zanuck was hoping that his<br />

number one male star before the war would soon<br />

be back from service, so he delayed production<br />

for several months. Tyrone Power, whose last two<br />

films, The Black Swan and Crash Dive , were<br />

released in 1942 and 1943, had spent three-anda-half<br />

years in the Marines. Beginning as a<br />

private, he was discharged in late November,<br />

1945 as a first lieutenant with Squadron 353 of

the Marine Transport Command, having<br />

served in the Central and South Pacific. Zanuck<br />

had saved Captain from Castile in addition<br />

to The Razor’s Edge for Power.<br />

By November, 1945 Fox contract star Gene<br />

Tierney was assigned the female lead role of<br />

Isabel. Tierney and Power previously had been<br />

together in Son of Fury (1942). In the interim<br />

she had become an important star on the Fox<br />

lot after the astonishing success of Laura and<br />

then Leave Her to Heaven in 1945, the most<br />

commercially successful Fox film up to that<br />

point. Famed designer Oleg Cassini, Tierney’s<br />

husband, did her clothes for The Razor’s Edge.<br />

Shooting began on March 29, 1946 but at<br />

the helm was director Edmund Goulding – not<br />

George Cukor. In a letter to Cukor dated November<br />

14, 1945, Zanuck said in part:<br />

Now comes the big problem of your<br />

availability. [MGM executive Eddie]<br />

Mannix told me that there would not be a<br />

chance of your finishing your next as-<br />

signment [at MGM] before sometime in<br />

April, providing you get started the first<br />

week in January. And he was very doubtful<br />

about this starting date. If this is accurate<br />

– and Eddie was very definite about this<br />

point – it would be a terrible stumbling<br />

block for us. . . .<br />

Now it goes without saying that I want<br />

you above anyone else to direct this<br />

film. While we have some difficulties as<br />

to interpretations of certain sequences,<br />

I know that you are the man for the job,<br />

and I know that on these points you will<br />

be prepared to go along with me and<br />

accept my instinctive feelings about them.<br />

After all the work you have done on the<br />

script and in the production preparation, it<br />

would be a pity if you could not do the<br />

film, but if what Mannix told me on<br />

Monday is true, then I know you are not<br />

going to be available. . .<br />

Due to the scheduling conflict and the<br />

previous decision to delay production, it was<br />

determined that Cukor would have to bow out<br />

in late November. Shortly thereafter Edmund<br />

Goulding signed a long-term contract with Fox<br />

and was handed The Razor’s Edge. He had<br />

directed Claudia in 1943 for Fox and everyone<br />

was very happy with the results. Prior to Claudia<br />

he had been at Warner Bros. for several<br />

years having directed such well-received films<br />

as The Dawn Patrol (1938), Dark Victory<br />

(1939), The Old Maid (1939), etc. Earlier at<br />

MGM he directed Grand Hotel (1932), Riptide<br />

(1934), and various others. Goulding’s primary<br />

strength was in working with the actors,<br />

responding to their needs, creating a happy atmosphere<br />

on the set, and being psychologically<br />

“in tune” with each of the players.<br />

“I don’t recall a set where there was more<br />

cheerfulness, much of it provided by our very<br />

British director, Edmund Goulding,” wrote<br />

Gene Tierney in her autobiography Self-Portrait.<br />

“When he wanted to describe to you how

a particular scene should be played, he would<br />

step in front of the camera and say, ‘May I be<br />

you?’ Then he would promptly act out the entire<br />

scene.”<br />

Fox cinematographer Arthur Miller was<br />

assigned The Razor’s Edge. He had won<br />

Academy Awards for his work on How Green<br />

Was My Valley (1941), The Song of Bernadette<br />

(1943), and was about to win yet another for<br />

Anna and the King of Siam (1946).<br />

“Edmund Goulding . . . used a system of<br />

photographing each complete sequence from<br />

beginning to end with the camera shooting<br />

from a crane following the actors. This was<br />

supposed to achieve a continuous, smooth fluid<br />

action,” Miller wrote in 1967. “We rehearsed<br />

all morning and made the take before lunch,<br />

then rehearsed another sequence during the<br />

afternoon and shot it all before leaving the studio<br />

in the evening. The actors were required to<br />

memorize the dialogue for the entire sequence<br />

and had to make all their moves and pauses<br />

for dialogue precisely to the marks made during<br />

the rehearsals, so that the movement of the<br />

crane and the action would coincide. Zanuck<br />

looked at the rushes for about three days before<br />

deciding that both the action and dialogue appeared<br />

mechanical. He then called a halt to this<br />

method of shooting. Zanuck wanted medium<br />

shots and plenty of close-ups to play with<br />

when the time came to edit a picture.”<br />

In viewing the finished film, it appears that<br />

in reality a compromise (or blend) was made<br />

between Goulding’s approach and Zanuck’s<br />

insistence on breaking up the long takes for<br />

editorial flexibility.<br />

The Razor’s Edge was a long shoot. 83 days<br />

were estimated but the final count was 95. This<br />

was the longest filming schedule in 20 th Century-Fox’s<br />

history up to then. Although “about<br />

$4,000,000” was publicized at the time as the<br />

production’s cost, according to Fox in-house<br />

records, it actually came in at $3,355,000 –<br />

which was a lot for a black-and-white noncostume<br />

epic at that time. And it was a very<br />

long picture at 146 minutes. Before Zanuck<br />

trimmed it, the film was even longer – including<br />

a programmed intermission that was deleted<br />

prior to opening.<br />

The production values were quite opulent,<br />

including 89 full-scale sets, often with great<br />

depth, that were beautifully rendered and<br />

dressed at a total cost of $641,800 1946 dollars.<br />

In addition there were hordes of extras in<br />

many of the settings. The only jarring notes<br />

from a production standpoint are the obvious<br />

painted backing of the Himalayas behind the<br />

holy man’s domicile and a phony composite<br />

shot with clouds at the climax of Larry’s India<br />

pilgrimage.<br />

After editing and then scoring by Alfred<br />

Newman, the film was sneak-previewed. Zanuck<br />

sent a memo to Spyros Skouras, president<br />

of Fox, on October 28, 1946. He said in part:<br />

An additional forty-two preview cards<br />

came in the mail today on The Razor’s<br />

Edge. . . . To date we have a total of one<br />

Production crew prepares for the country club scene.<br />

hundred and twenty-four cards [in addition<br />

to the ones filled out and handed in after<br />

the preview at the theatre].<br />

The cards are divided as follows:<br />

fifteen are marked good or very good,<br />

one hundred and nine are marked excellent<br />

or superb.<br />

This is the only preview we have had<br />

on any film where no cards were marked<br />

fair or bad. . . . Many cards openly state<br />

that the picture, in addition to being<br />

outstanding entertainment, made a great<br />

impression on them . . . .<br />

Altogether they are the most unusual<br />

and outstanding set of preview cards we<br />

have ever had on any film.<br />

Although The Razor’s Edge received mixed<br />

reviews when released in November, 1946, it<br />

became Fox’s biggest hit at the box office up

to then. Obviously, the timing of the subject<br />

matter was a major factor. Nominated for best<br />

picture by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts<br />

and Sciences, it lost to The Best Years of Our<br />

Lives. Other nominees for best picture that year<br />

were It’s a Wonderful Life, The Yearling, and<br />

the British Henry V. Anne Baxter received the<br />

Academy’s best supporting actress award for<br />

her role in The Razor’s Edge.<br />

In The Encyclopedia of Novels into Film<br />

(1998), there is an accurate breakdown by<br />

Stephen C. Cahir regarding the differences<br />

between Maugham’s novel and the 1946 film:<br />

here are a few heavily condensed excerpts from<br />

Cahir’s text:<br />

Generally, the film is a very faithful<br />

rendition of the novel. However, . . . .<br />

the film’s focus is on the love story<br />

involving Isabel, Larry, and Sophie. . . .<br />

Sophie (Anne Baxter), absent from much<br />

of the book, is a major character in the<br />

film. The novel’s focus, Larry’s search for<br />

meaning, is greatly abbreviated. . . .<br />

The film simplifies the philosophical-<br />

religious aspect of the story. . . . No<br />

reference is made to Hinduism. . . .<br />

Larry’s enlightenment occurs in an off-<br />

screen instant. . . .<br />

The limited sexuality of the novel is<br />

completely omitted from the film,<br />

understandably a concession to 1946<br />

censors. Sophie’s sexual experiences<br />

are only implied, Larry’s are not men-<br />

tioned, and Suzanne Rouvier, the would-<br />

be artist with many lovers, does not<br />

appear at all. . . .<br />

On October 18, 1948 Lux Radio Theatre,<br />

then the most important dramatic show in broadcasting,<br />

presented their adaptation of the 1946<br />

film. Ida Lupino played Isabel, Mark Stevens<br />

was Larry, Edgar Barrier portrayed Somerset<br />

Maugham, Joseph Kearns was Elliott Templeton,<br />

and Frances Robinson played Sophie.<br />

The only theatrical remake of The Razor’s<br />

Edge was released in 1984, although it seems<br />

that the late 1960s and early 1970s would have<br />

been more timely for another version. This was<br />

the period of the anti-establishment hippie culture,<br />

during which some individuals and groups<br />

made pilgrimages to India in search of inner<br />

peace and insights at the feet of a guru. Unlike<br />

the studio-bound 1946 version, for the 1984 film<br />

some actual locations were used – particularly<br />

India to good effect.<br />

Larry was played by Bill Murray, Isabel was<br />

Catherine Hicks, Sophie – Theresa Russell, and<br />

Elliott Templeton was portrayed by Denholm<br />

Elliott. Somerset Maugham’s character on screen<br />

was jettisoned on this occasion.<br />

Before moving on to Alfred Newman’s music<br />

for the 1946 Razor’s Edge, a brief interlude on<br />

the advertising art for the film..<br />

Rudy Behlmer is the author of<br />

Behind the Scenes: The Making of . . . ,<br />

Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck,<br />

Inside Warner Bros (1935-1951), etc.<br />

The director demonstrates how<br />

to play a particular scene with<br />

leading lady Gene Tierney.

he most popular<br />

American illustrator<br />

of his era, Norman<br />

Rockwell, was engaged<br />

by 20th Century-Fox’s<br />

director of advertising and<br />

publicity Charles Schlaifer<br />

to create a painting for<br />

The Razor’s Edge to be<br />

used on billboards and in<br />

magazines and newspapers.<br />

Schlaifer had previously<br />

hired him to paint the<br />

promotion and advertising<br />

art for Fox’s The Song of<br />

Bernadette (1943).<br />

Rockwell is particularly<br />

famous for his over 300<br />

Saturday Evening Post<br />

magazine cover paintings<br />

that began in 1916 and<br />

ended 47 years later when<br />

he switched to Look magazine<br />

for a ten-year run. The<br />

earlier decades were when<br />

general interest magazines<br />

represented the dominant<br />

form of home entertainment.<br />

Rockwell’s sometimes<br />

poignant, sometimes<br />

humorous scenes of Ameri-<br />

cana depicted life as he (and his audience)<br />

wished it to be. Said the artist: “I unconsciously<br />

decided that if it wasn’t an ideal<br />

world, it should be.”<br />

Immensely prolific over the decades, he<br />

illustrated books, magazine stories, painted<br />

advertisements, Christmas cards, calendars,<br />

postal stamps, playing cards, murals, etc.<br />

The output had an emotional quality that<br />

gave personal meanings to many different<br />

kinds of people.<br />

Rockwell was commissioned to create<br />

the advertising art for a few films over<br />

the decades, including Orson Welles’ The<br />

Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and the 1966<br />

remake of Stagecoach.<br />

“Whenever we got the idea that we<br />

needed outside art, we always went to fine<br />

artists,” recalled Fox’s Charles Schlaifer.<br />

“Norman Rockwell’s art for Bernadette<br />

was one of the most effective pieces . . .<br />

ever created for a motion picture. When he<br />

said that he’d have to charge me a lot of<br />

money – ‘twenty-five’ – I thought he meant<br />

$25,000, but he meant $2,500.<br />

“I used him again on Razor’s Edge and,<br />

after Bernadette, every other film company<br />

hired him at $25,000 for a piece of work.”<br />

For The Razor’s Edge Fox launched the<br />

most extensive billboard campaign in the<br />

history of the corporation up to that time.<br />

—R.B.

lfred Newman’s affinity for spiritual<br />

matters was always apparent,<br />

especially in his music for such films<br />

as The Song of Bernadette, The Keys of the<br />

Kingdom, The Robe and The Greatest Story<br />

Ever Told – all of which dealt with aspects of<br />

Christianity, from ordinary men and women<br />

who lived holy lives to the death and<br />

resurrection of Jesus himself. But with The<br />

Razor’s Edge, Newman faced a unique challenge:<br />

A man’s quest for universal truths that takes<br />

him into the Hindu belief system and beyond.<br />

In 1946, Newman was at the top of his<br />

game. He had won three Academy Awards (for<br />

Alexander’s Ragtime Band, Tin Pan Alley and<br />

Song of Bernadette) and 18 additional Oscar<br />

nominations for his work on such classics as<br />

The Hurricane, The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering<br />

Heights and How Green Was My Valley. He<br />

ran the 20th Century-Fox music department<br />

and regularly conducted an orchestra of<br />

Hollywood’s finest musicians.<br />

Newman’s boss, Darryl F. Zanuck stated in a<br />

1945 memo: “This is the only picture that I am<br />

going to put my name on as an individual<br />

producer this year.” That made it Newman’s<br />

number-one priority for 1946 as well, although<br />

he also worked that year on Centennial<br />

Summer, Three Little Girls in Blue, Margie,<br />

The Shocking Miss Pilgrim and My Darling<br />

Clementine – as well as supervising or<br />

conducting many other Fox films being scored<br />

by other composers.<br />

Newman’s involvement began even before<br />

production commenced, in part because Zanuck<br />

agreed (presumably at director Edmund<br />

Goulding’s request) to have a small orchestra on<br />

the set throughout much of the filming. Records<br />

at Local 47 of the American Federation of<br />

Musicians indicate that, from late March through<br />

the end of May, as many as 17 sideline players<br />

(sometimes, records say, for “atmosphere”) were<br />

employed for The Razor’s Edge.<br />

“It created a mood that often is lacking on<br />

cold sets,” Goulding later told a Fox publicist.<br />

“In the silent days the practice of playing music<br />

on the stages was very effective but, because of<br />

sound, it seldom is employed today.” On<br />

several of the days, it wasn’t just any random<br />

group of freelance musicians, either – it was the<br />

orchestra of John Scott Trotter, perhaps best<br />

known as Bing Crosby’s musical director for<br />

many years.<br />

In addition, Newman oversaw the choices<br />

and arrangements of a good deal of source<br />

music for the film, including several songs for<br />

which on-set playback would be necessary.<br />

Music for dancing at Elliott Templeton’s party,<br />

for example, and the scenes of Parisian<br />

nightlife that featured musicians on-camera,<br />

required advance work by Newman’s associates<br />

And then there was the matter of Goulding’s<br />

insistence upon contributing to the score via<br />

songs of his own composition (see sidebar).<br />

This required Fox music department personnel<br />

to take down Goulding’s whistled tunes and<br />

adapt them for appropriate use in the film. His<br />

“J’aime ta Pomme,” the Parisian café music<br />

associated with Sophie, required several<br />

arrangements, mostly for small ensemble<br />

including accordion, violin, bass and drums.<br />

Most of<br />

these were<br />

written by<br />

Fox veteran<br />

Arthur<br />

Morton.<br />

Maurice<br />

dePackh,<br />

another

studio regular, wrote the arrangement of “Night<br />

Was So Dark,” the Russian café piece that<br />

features balalaikas, domra and cimbalom; Fox<br />

vocal coach Charles Henderson was credited<br />

with the vocal arrangement for the Russian<br />

singers. Herb Taylor also contributed a handful<br />

of arrangements of source music, some used,<br />

some not.<br />

The lavish Chicago party that begins the<br />

film features several standards, including “April<br />

Showers,” “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” and<br />

“Missouri Waltz,” all arranged by Newman’s<br />

regular orchestrator Edward Powell; and “I’ll<br />

See You in My Dreams,” arranged by Herbert<br />

Spencer.<br />

It even fell to the music department to<br />

arrange for a piano coach for Clifton Webb,<br />

who as Templeton was to be seen playing<br />

Chopin; this was done, department notes<br />

indicate, on March 22 in “Mr. Newman’s<br />

bungalow.” (There is no such scene in the final<br />

cut, although Chopin’s “Polonaise” is heard<br />

playing in the Paris rooming house where Larry<br />

Darrell lives.) Alfred’s brothers Lionel and<br />

Emil were peripherally involved, too,<br />

conducting source cues for playback during the<br />

shooting process.<br />

These were relatively easy tasks to assign<br />

and accomplish. The more critical work of<br />

creating the original dramatic score was left to<br />

Newman and Powell, and this was probably<br />

done in August 1946 as recording occupied<br />

much of September.<br />

Evaluating the script, the rough cut and the<br />

performances, as he always did, Newman<br />

decided to write two main themes: one for<br />

Larry’s relentless search for the meaning of life,<br />

which the composer called “The Pursuit of<br />

Knowledge,” and another for the complex<br />

relationship of Larry and Isabel, which<br />

Newman titled “Seduction.”<br />

In an experiment that would rarely be<br />

repeated at Fox, Zanuck asked Newman to<br />

compose the score for Larry and Isabel’s Paris<br />

love scene before shooting, so that it could be<br />

played back on the set while Tyrone Power and<br />

Gene Tierney were playing their parts.<br />

Sixty years later, it is impossible to know for<br />

certain why this unusual request was made. But<br />

one possible reason involves the gamble that<br />

Zanuck knew he was taking with The Razor’s<br />

Edge – an expensive movie based on a novel<br />

that, because it was essentially about ideas,<br />

religion and philosophy, many thought was<br />

unfilmable and might not attract a wide<br />

audience – and a giant promotional opportunity<br />

being offered by Life magazine in advance of<br />

the film’s release.<br />

Life was the nation’s most popular weekly,<br />

reportedly read by one of every three<br />

Americans in that era. Editors proposed to<br />

“explain the enormously complicated process<br />

of making such a movie” by selecting a single<br />

sequence and having a photographer capture on<br />

film all of the many crafts it took to bring one<br />

scene to life. The scene chosen was the Power-<br />

Tierney kiss, and the results were printed on<br />

nine consecutive pages of the August 12, 1946<br />

issue. Included was a shot of Newman<br />

conducting the Fox orchestra and a second<br />

photograph of two pages of the conductor’s<br />

score for the scene.<br />

The movie would not actually be scored<br />

until September. But Fox cooperated fully with<br />

Life’s photographer and reporters and, in order<br />

to include the process of music, something had<br />

to be written and recorded for playback on the<br />

set. This may also explain why “Seduction” is<br />

effectively a more sophisticated version of a<br />

theme Newman had written a decade earlier for<br />

the Samuel Goldwyn film These Three. Either<br />

Newman felt that it was a good theme, long<br />

forgotten, that might work for Larry and Isabel;<br />

or that it was a temporary solution to an<br />

immediate problem that could always be<br />

replaced later, but wasn’t – perhaps, again,<br />

because Goulding and<br />

Zanuck fell in love with it<br />

(as often happens in films<br />

today with “temp tracks,”<br />

temporary music placed in<br />

the film during early postproduction,<br />

usually prior<br />

to the composer’s<br />

involvement).<br />

A close look at the<br />

score as reproduced in the<br />

tiny photograph in Life<br />

reveals that it was, indeed,<br />

the “Seduction” music<br />

used in the final film,<br />

meaning that the music<br />

(probably with minor tweaks) remained in the<br />

score months after the magazine photo-op.<br />

Regardless of the origins of the love theme,<br />

it turned out to be just right for the film, its<br />

yearning nature giving voice to the desire felt<br />

by both Larry and Isabel, one that was never to<br />

be consummated.<br />

The theme for Larry’s quest, “The Pursuit of<br />

Knowledge,” must have been far more difficult<br />

for Newman – attempting to define in music the<br />

search for answers to the whys and wherefores<br />

of man’s existence, the same questions that<br />

have been asked by so many for thousands of<br />

years. There is something mysterious and<br />

questioning but also an undeniable nobility to<br />

this theme, just as there is something noble and<br />

pure about Larry, especially after his visit to the<br />

Himalayas and the answers he finds there.

In fact, the high point of the score may be the 12<br />

minutes of music that follow Larry to India and his<br />

epiphany at the top of the world (tracks 16 and 17).<br />

The music of these scenes alternates between<br />

variations on “The Pursuit of Knowledge” and a<br />

secondary theme, “The Philosopher,” for the Holy<br />

Man (Cecil Humphreys) whom Larry encounters and<br />

who urges him forward on his journey. This theme is<br />

initially voiced by the clarinet, later by the French horn.<br />

There are several other, minor, Newmancomposed<br />

pieces in the score, most of which are<br />

source cues designed to evoke the proper mood<br />

during festivities in Chicago and Paris: “A Chicago<br />

Country Club” (track 4) appears twice during the<br />

movie’s opulent initial party; “Le Bistro” and<br />

“Chemin de Compagne” (in track 8), the can-can<br />

“Café Francais” (which opens track 12); “The<br />

Wedding Cake” and “After the Wedding,” (tracks 13<br />

and 14), a waltz and another dance number for the<br />

marriage of Isabel and Gray; “The Ritz” and<br />

“Cocktails” (track 21), another pair of delightful<br />

waltzes for a sophisticated Paris restaurant;<br />

“Oboesque” (track 23), an exotic, Eastern-sounding<br />

backdrop for the opium den where Larry finally finds<br />

Sophie; “The Photograph” (track 24), in the aftermath<br />

of Sophie’s death, and “Farewell” (track 25), which<br />

follows Elliott’s death.<br />

“Joan and Don,” for a scene with Maugham and a<br />

princess (track 19), was actually written by Newman<br />

for Joan Bennett and Don Ameche in the 1942 Fox<br />

film Girl Trouble. “The Parisian Trot” (the lively<br />

piece in track 11) is a Lionel Newman-Charles<br />

Henderson composition. Newman’s staff also<br />

discovered a pair of traditional French folk tunes,<br />

“Aupres de ma Blonde” and “Les Trois Capitaines”<br />

(track 15) to underscore the scene with Larry and a<br />

fellow miner in a bistro.<br />

Alfred Newman finished the recording with a 93piece<br />

orchestra on September 14, 1946, but returned<br />

– probably after final trims by Zanuck – on<br />

September 30 to re-record, again with a 93-piece<br />

orchestra, the main title, finale and trailer music. A<br />

few of the November 1946 reviews cited Newman’s<br />

contribution to the film, although by now, the critics<br />

took a ho-hum attitude because of his extraordinary<br />

track record: “The music supplied by Alfred Newman<br />

is just one more of his superior attainments,” said The<br />

Hollywood Reporter.<br />

He revisited the music of The Razor’s Edge only<br />

once, when he re-recorded seven of his most famous<br />

movie themes for Mercury Records. He asked Powell<br />

to arrange a three-and-a-half minute version of<br />

“Seduction,” and it was recorded in October 1950. (In<br />

fact, Newman used the back cover of his coffeestained<br />

conductor book for Razor’s Edge to work out<br />

the sequencing of that album.)<br />

Alfred Newman’s score for The Razor’s Edge was<br />

not among the film’s Academy Award nominees for<br />

1946. The Fox score nominated that year was<br />

Bernard Herrmann’s work for Anna and the King of<br />

Siam, although Newman’s music direction on Jerome<br />

Kern’s Centennial Summer was nominated in the<br />

“scoring of a musical picture” category. Nonetheless,<br />

the music of The Razor’s Edge remains a landmark in<br />

the history of Fox scores, and one of Newman’s most<br />

powerful works.<br />

Jon Burlingame writes about movie music for<br />

Daily Variety and The New York <strong>Time</strong>s.<br />

He is the author of<br />

Sound and Vision: 60 Years of Motion Picture<br />

Soundtracks, and he teaches film-music history at USC.

dmund Goulding, already famous as<br />

the director of Grand Hotel and Dark<br />

Victory before he received the assignment<br />

to helm The Razor’s Edge, was also an<br />

accomplished tunesmith.<br />

Goulding was what the music business call<br />

s a “hummer” - in the same sense as Charles<br />

Chaplin - when it came to music for their films.<br />

Chaplin would hum, whistle, sometimes plunk<br />

out a tune on the piano for his composers, who<br />

would then translate these simple melodies into<br />

a score by creating harmonies and countermelodies<br />

and fully orchestrating them for<br />

performance in the movie. Goulding actually<br />

preferred to whistle his tunes.<br />

“Ever since I was a youngster I wanted to be<br />

a composer,” Goulding told a Fox publicist for the<br />

Razor’s Edge pressbook. “Someday, when and<br />

if I ever stop directing films, I’m going to do<br />

nothing else but sit at my piano from morning<br />

until night writing all the music inside of me and<br />

giving expression to the hundeds of tunes that<br />

I’ve been carrying around in my head.”<br />

According to a 1947 profile in <strong>Time</strong> magazine,<br />

it began when Goulding was unhappy with a<br />

line reading Gloria Swanson gave in his early<br />

talkie The Trespasser and decided to “divert the<br />

audience’s attention with background music,”<br />

specifically a tune of his own. “Love, Your Spell<br />

Is Everywhere,” with lyrics by Elsie Janis, was<br />

played in the film and later recorded by<br />

bandleader Ben Selvin, who had a top-10 hit<br />

with it in late 1929.<br />

Other songs followed: “You Are a Song,” with<br />

lyrics by the great Leo Robin, for The Devil’s<br />

Holiday (1930), and which Goulding actually<br />

sang on a CBS radio broadcast; music for<br />

Blondie of the Follies (1932) and Riptide (1934);<br />

and “Oh Give Me <strong>Time</strong> for Tenderness,” again<br />

with lyrics by Janis, for the Bette Davis classic<br />

Dark Victory (1939).<br />

For The Razor’s Edge, Goulding wrote three<br />

songs, two of them ephemeral source tunes –<br />

“Night Was So Dark” for the Russian singers in<br />

a Parisian nightspot, “The Miner’s Song” for<br />

laborers emerging from underground – and one,<br />

“J’aime ta Pomme,” that was not only more<br />

prominent in the film but, in a later incarnation<br />

as “Mam’selle,” destined to become a pop hit.<br />

Goulding’s first two songs in Razor’s Edge<br />

are functional and used only once as on-screen<br />

source pieces. “Night Was So Dark” appears about<br />

35 minutes into the film, as Larry and Isabel are<br />

enjoying a final night together in Paris. They visit<br />

a Russian café where a nine-man ensemble –<br />

three on stage, six strolling through the room – is<br />

playing traditional Russian folk instruments,<br />

including balalaikas and domras, and serenading<br />

diners. The lyrics, written by famed Russian<br />

soprano Nina Koshetz, who was now living in<br />

Southern California and had worked with Newman<br />

as chorus leader on the 1934 Goldwyn film We<br />

Live Again. Their English translation:<br />

Night was so dark<br />

Not a trace of stars<br />

No, never could I forget that night<br />

In that dark night

Love shone through the dark<br />

But alas, we had to part<br />

Like a gust of wind<br />

Like a whirlwind storm<br />

I would fly after you<br />

Above the mountains<br />

Like a brave wild falcon, I would soar<br />

There isn’t any happiness for me any more<br />

Could I ever bring you back to me<br />

Never to forget you – Never.<br />

(The Razor’s Edge conductor books, both in the<br />

Newman Collection at USC and the originals at<br />

Fox, have the actual lyrics in Russian script, as<br />

they were sung and played by Russian-speaking<br />

extras during shooting. The translation was found<br />

in the continuity script in the Fox collection at USC.)<br />

The “Miner’s Song” appears about 46 minutes<br />

into the picture, and is heard only briefly as raucously<br />

sung by Larry’s French friends after a long day’s<br />

work in the mines. The lyrics were penned by<br />

Jacques Surmagne, a Frenchman who may have been<br />

a Fox employee (his name later resurfaces as an<br />

associate producer on television’s 20th Century-<br />

Fox Hour in the 1955-56 season).<br />

More importantly, Surmagne wrote the words to<br />

Goulding’s haunting tune for the film’s doomed<br />

Sophie (Anne Baxter), “J’aime ta Pomme.” Although<br />

this song does not surface until an hour and 23 minutes<br />

into the film, it becomes one of the key themes of<br />

the score because of its association with Sophie,<br />

Larry’s affection for her, and her tragic demise.<br />

It’s a deeply felt love song in the classic French sense,<br />

and in its longest incarnation it goes like this:<br />

J’aime ta pomme, pomme-pom,<br />

Ta jolie pomme, pomme-pom,<br />

Et j’aime entendre tes mots tendres<br />

Me griser toujours,<br />

Je suis a toi, ma pomme,<br />

Tu es a moi, ma pomme,<br />

Et dans mes bras, tu connaitras,<br />

La valse d’amour<br />

Et blonde ou brune<br />

Quand un chacun trouve sa chacune<br />

Au clair de la lune,<br />

En la prenant tendrement dans ses bras<br />

d’amant<br />

Il lui dit tout bas,<br />

Viens danser avec moi, viens tous les<br />

deux, ma pomme,<br />

Si tu le veux, ma pomme, dans le pays de<br />

paradis de notre grand amour.<br />

Je suis a toi, pomme-pom,<br />

Tu es a moi, pomme-pom,<br />

Et dans mes bras tu connaitras la valse<br />

d’amour.<br />

The studio’s official English translation:<br />

I love your face, Pomme-pom,<br />

Your pretty face, Pomme-pom,<br />

I like to hear your tender words<br />

That intoxicate me always –<br />

I belong to you, my apple,<br />

You belong to me, my apple,<br />

And in my arms you’ll know<br />

The waltz of love.<br />

And blonde or brunette,<br />

When a he meets a she<br />

In the light of the moon,<br />

Taking her in lover’s arms<br />

He tells her softly:<br />

Dance with me, come both of us, my apple,<br />

If you want, my apple, to the paradise<br />

country of our great love.<br />

I belong to you, Pomme-pom,<br />

You belong to me, Pomme-pom,<br />

And in my arms you’ll know the<br />

waltz of love.<br />

“J’aime ta Pomme” appears in various arrangements,<br />

from an initial<br />

on-screen performance in<br />

the French café to a ghostly<br />

reprise in Sophie’s mind as<br />

she takes up the bottle again<br />

to forget her dead husband<br />

and child. Most of these were<br />

written by Arthur Morton and<br />

are labeled variously “café<br />

arrangement,” “tango arrangement,”<br />

“parting arrangement,”<br />

although one, labeled “reunion<br />

arrangement,” was penned by<br />

Herb Taylor (frequent orchestrator<br />

for Dimitri Tiomkin and composer<br />

of TV’s Death Valley Days theme).<br />

Goulding’s tune, and<br />

Morton’s various versions of<br />

it, are wonderfully French in<br />

mood and color. The film’s<br />

box-office popularity made exploitation of a<br />

musical theme a clear promotional opportunity,<br />

and “J’aime ta Pomme” was an obvious choice.<br />

Lyricist Mack Gordon, whose 1943 Oscar (for<br />

“You’ll Never Know” from Hello, Frisco, Hello)<br />

and five other nominations were all for Fox<br />

films, took Goulding’s music and added a new<br />

English-language lyric for commercial release.<br />

The new ballad was called “Mam’selle” and<br />

told the story of a late-night romantic rendezvous<br />

in Montmartre. Artists lined up to record it, and<br />

there were no fewer than six top-10 records of<br />

the song in April and May of 1947. Two (the<br />

versions by Art Lund and Frank Sinatra) went to<br />

no. 1. Two others (by Dick Haymes and the Pied<br />

Pipers) went to no. 3. It spent three weeks at no. 1<br />

on radio’s popular Your Hit Parade and spent<br />

19 weeks all told on the Hit<br />

Parade’s top 10 list (basically<br />

all spring and summer).<br />

Records by Dennis Day and<br />

Frankie Laine were also hits,<br />

and in subsequent years the<br />

roster of artists who recorded<br />

“Mam’selle” included Tony<br />

Bennett, Nat<br />

King Cole, Vic Damone, Robert<br />

Goulet and Lawrence Welk.<br />

The Goulding profile<br />

in <strong>Time</strong> claimed that he<br />

“objected to the music<br />

written for a Montmartre<br />

café scene. He whistled a<br />

new tune, which was picked<br />

up by a studio accordion<br />

player and transcribed for<br />

orchestra.” Sixty years later,<br />

it’s hard to know how much of that story is fact<br />

and how much is press-release fancy – but the<br />

popularity of the song is undeniable, and the latter<br />

part of the <strong>Time</strong> story is probably true: “The<br />

studio got 5,000 letters asking about the song…<br />

`Mam’selle’ jumped from 25th to first place on<br />

sheet-music best-seller lists in 10 weeks.”<br />

— J.B.

1. Main Title 1:35 The Razor’s Edge opens<br />

with Alfred Newman’s magnificent theme<br />

“The Pursuit of Knowledge”, which plays<br />

during the entire main title sequence.<br />

2. “April Showers” 2:51 After a spoken<br />

introduction<br />

by Herbert<br />

Marshall in<br />

the role of<br />

Somerset<br />

Maugham,<br />

the story<br />

begins at<br />

a Chicago<br />

country club dinner party early in the 1920’s<br />

where Elliott Templeton (Clifton Webb)<br />

explains away Maugham’s presence at the<br />

party to his sister Louisa (Lucile Watson)<br />

by declaring that “authors go everywhere<br />

nowadays.” While the orchestra continues to<br />

play “April Showers” by Louis Silvers and B.<br />

G. DeSylva, Elliott and Louisa discuss Larry<br />

Darrell, a “loafer” for whom Elliott has nothing<br />

but contempt.<br />

3. “I’ll See You in My Dreams” 2:02 Joining<br />

the party are Isabel Bradley (Gene Tierney)<br />

and Sophie Nelson (Anne Baxter). Isabel compliments<br />

Sophie on her gown. Sophie confesses<br />

that it’s all for her fiancé, Bob MacDonald. The<br />

country club orchestra plays “I’ll See You In<br />

My Dreams” by Isham Jones and Gus Kahn.<br />

4. “A Chicago Country Club Dance” 2:02<br />

An original fox trot by Alfred Newman is<br />

played while Sophie and Somerset Maugham<br />

discuss Elliott Templeton. “They laugh behind<br />

his back but eat his food and drink his wine,”<br />

Maugham observes. Into the scene enters<br />

Isabel’s fiancé Larry Darrell (Tyrone Power).

5. “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” 1:45<br />

The gay, carefree atmosphere continues to<br />

the strains of “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles”<br />

by Jaan Kenbrovin (a collective pseudonym<br />

for James Kendis, James Brockman and Nat<br />

Vincent) and John William Kellette. Sophie<br />

introduces Maugham to her fiancé Bob Mac-<br />

Donald (Frank Latimore). While Sophie and<br />

Bob dance, Larry and Isabel steal away into<br />

the garden.<br />

6. “The Missouri Waltz” 1:48 Based upon<br />

a melody by John V. Eppel, “The Missouri<br />

Waltz” was arranged into song form by Frederic<br />

Knight Logan. The somewhat melancholy<br />

character of the tune underscores the frustration<br />

Isabel feels for Larry, who has just turned<br />

down a promising position. Isabel admonishes<br />

Larry that it is a man’s duty to take part in the<br />

activities of his country. Larry remains blithely<br />

unimpressed by Isabel’s scolding.<br />

7. “I’ll See You in My Dreams” 1:47 The<br />

popular favorite is reprised by the country club<br />

orchestra while Isabel and Larry discuss the<br />

future. She thinks it might be best if he goes<br />

away and, in fact, Larry is thinking of going<br />

to Paris to “clear his mind.” If he doesn’t find<br />

there what he is looking for, he will return to<br />

Chicago and take the first work he can get.<br />

8. Larry’s Journey Overseas 1:20 As<br />

Elliott describes how he will ensure that Larry<br />

leads a proper life with proper associates, we<br />

see Larry’s actual life in Paris. A musical montage<br />

comprised of “Le Bistro” and “Chemin<br />

de Compagne” underscores Larry as he lives<br />

the life of a bohemian and takes a garret in a<br />

small hotel.<br />

9. Isabel and Larry in Paris 1:46 Isabel<br />

has come to Paris and Larry tells her all about<br />

his life,<br />

that he is<br />

beginning<br />

to see<br />

things in<br />

a clearer<br />

light. He<br />

takes Isabel<br />

to his<br />

room. This<br />

cue marks the first appearance of Newman’s<br />

“Seduction” theme and, as we reach Larry’s<br />

hotel, it segues to the sound of a piano playing<br />

a Chopin polonaise, coming from another flat.<br />

10. Returned Engagement Ring :40<br />

Far from being<br />

impressed, Isabel<br />

tells Larry that<br />

she cannot live<br />

on $3,000 a year<br />

and she returns his<br />

engagement ring.<br />

11. Last Night Together 1:38 Isabel<br />

and Larry decide to have one last night<br />

together before she returns to America.<br />

She is determined it will be an evening he<br />

will never forget and that he will forsake<br />

his meandering existence. As she meets<br />

him on the staircase in her black Cassini he<br />

declares “I’ve never seen you so beautiful.”<br />

A montage of gay night spots (beginning<br />

with “The Parisian Trot” on the soundtrack)<br />

follows Larry and Isabel as they float from<br />

party to party.<br />

12. Night Clubbing 6:28 Larry and Isabel<br />

continue their spot-hopping, entertained by cancan<br />

dancers (with Newman’s “Cafe Francais”<br />

on the soundtrack), a Russian balladeer (Noel<br />

Cravat on-screen only) singing Edmund Goulding’s<br />

“Night Was So Dark,” and finally an early<br />

morning dose of Le Jazz Hot! The jazz rhythms<br />

(“Dardanella” by Felix Bernard) dissolove into<br />

an impassioned rendition of “Seduction” as<br />

Larry brings Isabel home and then says goodbye.<br />

But Isabel invites him in for one last drink. They<br />

kiss passionately.<br />

She removes<br />

her shawl and<br />

fingers his lapel<br />

A moment before<br />

surrendering to<br />

passion, Isabel<br />

retreats and asks<br />

Larry to leave. As dawn breaks she discovers<br />

uncle Elliott waiting up for her.

13. The Wedding Cake :50 A brief transition<br />

cue, a waltz by Alfred Newman, takes us to the<br />

wedding of Isabel and Gray Maturin (John Payne).<br />

14. After the Wedding :45 An original<br />

melody by Newman, this cue is reminiscent<br />

of the popular song “Every Little Movement<br />

Has A Meaning All Its Own.” Maugham<br />

wonders to Elliott what has happened to Larry<br />

Darrell. Elliott confides glibly, “Shall I tell you<br />

something my dear fellow - I don’t care a row<br />

of beans!”<br />

15. Miner’s Cafe 2:00 An accordion<br />

medley of the French<br />

folk tunes “Aupres<br />

de ma Blonde” and<br />

“Les Trois Capitaines”<br />

underscores a scene<br />

in a coal miners’ cafe<br />

where Larry and a fellow miner discuss the<br />

virtues of the East. The miner, an “unfrocked”<br />

priest, tells about a Holy Man in India who<br />

might be able to help Larry find himself. Note:<br />

the miners’ song described in the preceding<br />

profile of Edmund Goulding was recorded live<br />

on-set and was not among the pre-recorded<br />

music cues.<br />

16. Larry Travels to the East 5:15 Larry has<br />

traveled to India and<br />

meets the Holy Man<br />

(Cecil Humphreys).<br />

He tells him of his<br />

search for guidance.<br />

The Holy Man tells<br />

him “even to admit<br />

that you want to learn is in itself courageous...<br />

the road to salvation is as difficult as the sharp<br />

edge of a razor.” This cue is a medley of “The<br />

Pursuit of Knowledge” and “The Philosopher.”<br />

17. The Mountain Retreat 6:44 Larry<br />

climbs the mountain that overlooks the lamasery.<br />

He stays in a hovel retreat and is, in time, visited<br />

by the Holy Man. It is plain that Larry has<br />

experienced<br />

a profound<br />

awakening,<br />

about which<br />

he tells his<br />

mentor about.<br />

The man from<br />

the East is<br />

now convinced that it is time for Larry to go<br />

back and live in his own world.<br />

18. Larry and Maugham Reunited<br />

:11 In Paris,<br />

Maugham has<br />

a rendezvous<br />

with Larry,<br />

who begins<br />

to tell him of<br />

his time in<br />

India.<br />

19. Somerset Maugham and the<br />

Princess :41 Princess Edna Novemali<br />

inquires after Elliott Templeton. This waltz<br />

by Alfred Newman was originally composed<br />

in 1942 for the Fox picture Girl Trouble.<br />

20. The Rue De Lappe 2:47 Larry,<br />

Isabel, Gray and Maugham visit a Parisian<br />

dive, the Rue de Lappe. To their disbelief<br />

they meet Sophie MacDonald. Sophie, whose<br />

husband and infant child were killed in an<br />

auto wreck, has fallen into drunken debauchery.<br />

Introduced in this sequence is Edmund<br />

Goulding’s song “J’aime ta Pomme.”<br />

21. Cocktails<br />

at<br />

the Ritz<br />

1:52 Larry,<br />

empowered<br />

by his teachings<br />

in the<br />

East, has<br />

helped Sophie<br />

to wrestle herself from the bottle. In fact,<br />

they are to be married. They meet Maugham,<br />

Gray and Isabel at the Ritz for lunch. Elliott<br />

is there too, and passes judgment on the Princess<br />

Novemali. Elliott, forbidden by doctors<br />

to touch alcohol, implores his friends to try a<br />

rapturous Russian liqueur, Perzovka. Isabel,<br />

horrified at the idea of Larry and Sophie<br />

being married, goes over the top raving about<br />

the liqueur. It is all Sophie can do to restrain<br />

herself from imbibing. This cue features yet<br />

another original waltz by Alfred Newman.<br />

22. Sophie’s Torment 3:09 Isabel has<br />

brought Sophie to her home and, having planted<br />

seeds of doubt in her mind, leaves her alone with<br />

a bottle of Perzovka. Sophie takes the bait and,<br />

after downing a glass quickly refills it. Heard<br />

during this sequence is a far away reprise of

“J’aime ta Pomme.” As the veil lifts from the<br />

soundtrack the scene changes to the Rue de<br />

Lappe where Larry enters looking for Sophie.<br />

23. Oboesque 1:43 Larry is led by a taxi<br />

driver (Louis Mercier) to a middle eastern den<br />

of ill repute<br />

where<br />

Sophie is<br />

found in<br />

a drunken<br />

stupor.<br />

Larry tries<br />

to take her<br />

out but<br />

is tackled<br />

by a couple of denizens (Bud Wolfe and Fred<br />

Graham). While Larry fights off his attackers<br />

Sophie runs off into the rainy streets of Paris.<br />

Much of “Oboesque” is dialed out in the final<br />

dub of the picture.<br />

24. Sophie’s Room 2:13 A year later, news<br />

comes that Sophie has been murdered. The<br />

police take Larry and Maugham to see her room.<br />

There they<br />

find a photo<br />

of Sophie’s<br />

late husband<br />

and child.<br />

Larry picks<br />

up a volume<br />

of Keats<br />

and recites<br />

a verse that he used to read to Sophie when<br />

they were very young. As the inspector closes<br />

the room Larry and Maugham leave to visit a<br />

gravely ill Elliott Templeton in Nice.<br />

25. After Elliott’s Death 1:43 Maugham<br />

tells Isabel that Larry is leaving for America,<br />

working his way<br />

home on a tramp<br />

steamer. Despite<br />

Maugham’s warning,<br />

Isabel threatens<br />

to see Larry in<br />

America as often<br />

as she can.<br />

26. Finale :54 Larry has confronted Isabel over<br />

Sophie and he leaves confident that they will<br />

never see one another again. Maugham is awed<br />

by Larry’s inner spirit, proclaiming that “goodness<br />

is the greatest force in the world - and he’s<br />

got it.” The final shot shows Larry hauling bags<br />

of sail on the ship to America. With a mighty<br />

crash of a wave on screen and cymbals on the<br />

soundtrack we have reached THE END.<br />

27. Exit Music 4:13 This grand waltz was<br />

recorded during The Razor’s Edge scoring<br />

sessions, though it does not appear in the picture.<br />

While there is no documentation with reference<br />

to planned exit music, the fact that The Razor’s<br />

Edge was originally intended to have an intermission<br />

makes additional program music plausible.<br />

28. “J’aime ta Pomme” Demo 2:38 French<br />

actor and singer Louis Mercier recorded this<br />

demo of “J’aime ta Pomme.” It is not known if<br />

he was intended to sing the song at some point<br />

in the picture. He does appear as a taxi driver<br />

in the scene where Larry looks for Sophie.<br />

The take is, as you will hear, aborted. But we<br />

nevertheless felt Mercier’s rendition warranted<br />

inclusion on this CD.<br />

his compact disc of Alfred Newman’s<br />

complete score to The Razor’s Edge<br />

was produced using dual-angle<br />

recordings preserved in the 20th Century-<br />

Fox vaults. Originally stored individually on<br />

1000 ft. reels and later transferred to audio<br />

tape, the multiple angles were synchronized<br />

to produce a true stereophonic recording.<br />

The score was then assembled and mixed<br />

as it appeared in the final dub of the picture.<br />

The producers offer our profound merci<br />

beaucoups to Ned Comstock of USC;<br />

the wonderful staff at the Morion Picture<br />

Academy Library; Tom Cavanaugh of 20th<br />

Century-Fox; and special bows of gratitude<br />

to Rudy Behlmer for his superb essay on<br />

the making of The Razor’s Edge and to Jon<br />

Burlingame for his indispensable articles on<br />

both Alfred Newman’s music for the picture<br />

and the film’s director/songwriter Edmund<br />

Goulding.<br />

—Ray Faiola

Producers: Ray Faiola, Nick Redman and Craig Spaulding<br />

Film Notes: Rudy Behlmer • Music Notes: Jon Burlingame<br />

Audio Production: Ray Faiola, <strong>Chelsea</strong> <strong>Rialto</strong> <strong>Studios</strong><br />

Design: Charles Johnston<br />

For Twentieth Century-Fox: Tom Cavanaugh<br />

Still Photographs: Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences,<br />

University of Southern California - Alfred Newman Collection<br />

SPECIAL THANKS: Robert Kraft, Ned Comstock (USC), Stacey Behlmer,<br />

Barbara Hall, Jenny Romero (AMPAS), Fred Steiner and John Morgan<br />

A Screen Archives Entertainment Production<br />

THE RAZOR’S EDGE: Starring Tyrone Power, Gene Tierney, John Payne, Anne Baxter, Clifton Webb<br />

Lucile Watson and Herbert Marshall, Screenplay by Lamar Trotti based on the novel by W. Somerset Maugham,<br />

Musical score by Alfred Newman, Orchestrations by Edward Powell, Photographed by Arthur C. Miller,<br />

Edited by J. Watson Webb, Jr., Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck and Directed by Edmund Goulding<br />

Previous SAE-CRS Releases<br />

Distant Drums: Max Steiner and the United States Pictures Scores - A two-CD set featuring the scores<br />

to Cloak and Dagger, My Girl Tisa, South of St. Louis and Distant Drums • Pursued - Music by Max Steiner •<br />

Court - Martial of Billy Mitchell - Musical Score by Dimitri Tiomkin (includes Court-Martial Scenes with Cast) •<br />

Wilson - Music by Alfred Newman • Down to the Sea in Ships and Twelve O’Clock High - Music by Alfred Newman •<br />

Dragonwyck - Music by Alfred Newman • Irving Berlin’s Alexander’s Ragtime Band - Musical Direction by<br />

Alfred Newman • Captain From Castile - by Alfred Newman • Night And The City - Scores by Benjamin Frankel<br />

and Franz Waxman • The Blue Bird - Music by Alfred Newman • The Black Swan - Music by Alfred Newman • The<br />

Keys of the Kingdom - Music by Alfred Newman • The Foxes of Harrow - Music by David Buttolph • Son of Fury<br />

- Music by Alfred Newman • Marjorie Morningstar - Max Steiner<br />

Available through Screen Archives (540) <strong>63</strong>5-2575<br />

or online at www.screenarchives.com