Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

education<br />

– Presents –<br />

YOUR<br />

GUIDE TO<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>

Overture<br />

As CEO of <strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> I want to thank you for participating in this,<br />

our first opera education program.<br />

I believe music – especially opera, can add a great richness to life.<br />

My first exposure to music came as a little girl sitting under <strong>the</strong> piano listening to my<br />

grandmo<strong>the</strong>r play and sing operatic arias. I remember loving music and taking piano<br />

lessons. I guess I persisted with those scales long enough because I have from time<br />

to time throughout my life taught piano and of course that served as good grounding<br />

for what was to become a career.<br />

As for opera, it was love at first sight and sound. As a young person in former<br />

Yugoslavia, a student could attend opera for <strong>the</strong> equivalent of 25 cents. For me it was<br />

all magic, as I was instantly taken by this rich art form that actually brings toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

several o<strong>the</strong>r wonderful art forms such as… music, voice, sets, costumes, drama, love<br />

stories, lavish productions.<br />

Now you too will have a similar educational and experiential journey by being part<br />

of <strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s education program and Your Guide to <strong>Opera</strong>. We have created<br />

a thorough curriculum, practical and engaging teaching aids and yes, <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

for all to attend <strong>the</strong> dress rehearsal of an <strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> performance.<br />

This leads me naturally enough to tell you a bit about your hometown<br />

opera company.<br />

2<br />

First, I want to say what a great opera city we have here. We are a professional<br />

opera company backed by some of <strong>the</strong> greatest volunteers and corporate and civic<br />

leaders I have ever seen. I can’t tell you how fulfilling it is to be working with people,<br />

both staff and volunteers, who love opera and are willing to support it. <strong>Edmonton</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> is <strong>the</strong> oldest and largest professional, year-round opera company in <strong>the</strong> Prairie<br />

Provinces, one of 17 opera companies in Canada and <strong>the</strong> fourth largest in terms<br />

of budget and artistic output. It is also one of five flagship arts organizations in<br />

<strong>Edmonton</strong>.<br />

Your <strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> will be celebrating a 50 th birthday soon and that is a real<br />

statement about <strong>the</strong> kind of long term support <strong>Edmonton</strong> and area has for us and<br />

as well for many of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r arts and cultural organizations in this great city.<br />

So welcome to <strong>the</strong> wonderful world of opera. Enjoy and learn.<br />

Sandra Gajic<br />

CEO | <strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>

<strong>Opera</strong> Live!<br />

Nothing beats <strong>the</strong> excitement of live opera!<br />

For more information on how your class can attend<br />

a dress rehearsal at special student pricing, contact<br />

usby email at education@edmontonopera.com<br />

or visit us online at:<br />

www.edmontonopera.com<br />

3<br />

Contents<br />

Message from Director | 4<br />

Characters | 5<br />

Synopsis | 6–7<br />

The Story Behind <strong>the</strong> Story | 8<br />

Europe at <strong>the</strong> Time of <strong>Aida</strong> | 9<br />

Piecing Toge<strong>the</strong>r an Ancient World | 10<br />

Kings, Pharaohs and Queens of Egypt | 11<br />

Composer Biography | 10<br />

Librettist & Story Creator Biographies | 11<br />

Glossary | 12<br />

Activity 1: Listening Guide | 14<br />

Activity 2: Nationalism & Identity | 21<br />

Activity 3: Improv Reader's Theatre |21<br />

Activity 4: Poster Creation | 22<br />

Activity 5: Facebook Character Development | 23<br />

Activity 6: <strong>Opera</strong> Notes | 23<br />

A special thanks to volunteer editor, Stephan Bonfield –<br />

writer of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Aida</strong> Synopsis and Listening Guide.<br />

New to opera?<br />

Be sure to check out our Educator's Guide, Your Guide to <strong>Opera</strong>, available for<br />

free download online. It is designed to supplement this guide and offers an<br />

overview of <strong>the</strong> history of opera, activities for your class, and useful information<br />

about attending our dress rehearsals.

Message from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Director:<br />

Dejan Miladinovic<br />

The curious eyes of <strong>the</strong> 14-year-old boy followed <strong>the</strong> flickering torch carried by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Arab guide. The corridor was narrow and steep. Even with <strong>the</strong> torch, guide<br />

and visitors felt as if <strong>the</strong>y were engulfed by thousand-year-old darkness. The boy<br />

couldn’t believe that he was walking in <strong>the</strong> footsteps of pyramid robbers.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> main hall of <strong>the</strong> Cairo Museum <strong>the</strong> boy watched <strong>the</strong> colossal statues<br />

with curiosity. He hesitated for only a moment with slight fear touching his<br />

face at <strong>the</strong> entrance into <strong>the</strong> Mummy Room. At <strong>the</strong> exit door <strong>the</strong> boy stopped<br />

in front of <strong>the</strong> bust of Queen Nefertiti. Motionless, he stared in amazement at<br />

such incomparable beauty.<br />

The boy had a precious chance to visit <strong>the</strong> museum every day, week by week,<br />

thanks to his fa<strong>the</strong>r’s all-season engagement as a conductor with <strong>the</strong> newly founded<br />

Cairo Symphony Orchestra. As a conductor, <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r insisted that concert programs<br />

promote serious symphonic music composed by Arabs and Copts, such as Rahim,<br />

Khairat, El-Shawan or Greiss. So, <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> late Egyptian composer Greiss,<br />

a doctor in Egyptology, became <strong>the</strong> boy’s one-month teacher, telling him stories<br />

about ancient Egypt, its people, its customs, its Pharaohs, and its gods and deities.<br />

The curious boy was an attentive listener and a quick learner.<br />

One day, all three of <strong>the</strong>m – <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> Egyptologist and <strong>the</strong> curious boy –<br />

went to <strong>the</strong> Sahara Desert to visit a newly discovered tomb, a mastaba ("house for<br />

eternity") of a rich ancient Egyptian merchant. For <strong>the</strong> first time in his life <strong>the</strong> boy<br />

stepped on <strong>the</strong> Sahara sands. It was an unforgettable feeling. The Egyptologist told<br />

4<br />

<strong>the</strong> boy: “Grab a handful of sand from <strong>the</strong> spot where you left your footprint<br />

and take it with you. This sand will always be a link with what you have<br />

experienced and learned about ancient Egypt.”<br />

The Egyptologist was right. The boy was enchanted forever.<br />

When I staged <strong>Aida</strong> for <strong>the</strong> first time, memories of that teenage boy were awakened.<br />

Although I have since enriched my knowledge about <strong>the</strong> grand mystical culture of<br />

ancient Egypt, I have remembered in great detail all Dr. Greiss' stories. There is <strong>the</strong><br />

story about <strong>the</strong> final epic battle between <strong>the</strong> gods Horus and Seth, a metaphor for<br />

<strong>the</strong> everlasting battle between good and evil. There is <strong>the</strong> fascinating battle between<br />

<strong>the</strong> sun god Atum Ra and <strong>the</strong> monstrous snake Apophis (deification of darkness and<br />

chaos) in <strong>the</strong> underworld, which acts as a metaphor for <strong>the</strong> ending of one day and <strong>the</strong><br />

beginning of <strong>the</strong> next. I’ve heard <strong>the</strong> stories about <strong>the</strong> goddess Bastet with <strong>the</strong> head of<br />

a cat, known as “<strong>the</strong> devouring lady,” <strong>the</strong> lion-headed goddess of war Sekhmet and <strong>the</strong><br />

goddess Hathor, of feminine love, who has horns on her head. Above all, of course,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re’s <strong>the</strong> story about Ptah, creator of <strong>the</strong> universe.<br />

The last words in <strong>the</strong> opera – “Immenso Ptah...” – were <strong>the</strong> initial start for my<br />

directorial thoughts about staging Verdi’s <strong>Aida</strong>. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> battle between<br />

Atum Ra and Apophis is an excellent visual expression for <strong>the</strong> scene in which<br />

<strong>the</strong> sword is consecrated. The victory of Horus over Seth is <strong>the</strong> perfect triumphal<br />

representation of victory over Amonasro’s army. Thus, combining creative <strong>the</strong>atrical<br />

presentation with portions of <strong>the</strong> original spectacular rituals, along with emotionally<br />

strong personal scenes, is <strong>the</strong> proper way for reviving <strong>the</strong> spirit (Kha) of ancient<br />

Egypt. It seems to me <strong>the</strong> parts of my boyhood memories and <strong>the</strong> corresponding parts<br />

of Verdi's music are choosing each o<strong>the</strong>r by <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

In my directorial approach, I want to convey all my long-time intact excitements and<br />

emotions to <strong>the</strong> spectators, so <strong>the</strong>y could feel all <strong>the</strong> same as what <strong>the</strong> boy felt when he<br />

encountered <strong>the</strong> mummified time and space of <strong>the</strong> Pharaohs.<br />

Dejan Miladinovic<br />

August 2012

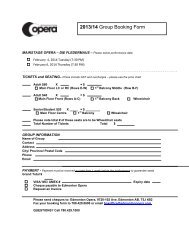

<strong>Aida</strong><br />

Education Dress Rehearsal<br />

Oct. 17 @ 11 am<br />

Jubilee Auditorium<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> 101<br />

Oct. 10 @ 7 pm<br />

Art Gallery of Alberta<br />

Ledcor Theatre<br />

Join us for a thought provoking discussion surrounding<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>. With special guests from <strong>the</strong> fields of music,<br />

history, political science, and classics.<br />

Admission is complimentary, but please<br />

RSVP at education@edmontonopera.com<br />

5<br />

Characters<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> – an Ethiopian Princess (soprano)<br />

Radamès – Captain of <strong>the</strong> Egyptian Guard (tenor)<br />

Amneris – Daughter of <strong>the</strong> King of Egypt (mezzo-soprano)<br />

Amonasro – King of Ethiopia, fa<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>Aida</strong> (baritone)<br />

Ramfis – High Priest of Egypt (bass)<br />

Pharaoh – King of Egypt (bass)<br />

The Priestess (soprano)<br />

Messenger (tenor)

Synopsis<br />

Written by Stephan Bonfield<br />

ACT I<br />

Egypt is again threatened by Ethiopia. An Egyptian officer, Radamès, is c hosen to<br />

command <strong>the</strong> attack force against <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians. Left alone on stage, Radamès sings<br />

of his love for <strong>Aida</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Ethiopian slave of Amneris, <strong>the</strong> Egyptian princess. Radamès<br />

dreams of triumph in battle and being granted a victory prize by Pharaoh – having his<br />

beloved <strong>Aida</strong> freed.<br />

Amneris enters, and it is soon clear that she loves and admires Radamès. However,<br />

when <strong>Aida</strong> follows Amneris shortly after, Amneris observes Radamès trying to conceal<br />

his glances toward <strong>Aida</strong>. In <strong>the</strong> trio that follows, Radamès worries that Amneris may<br />

have discovered his love for <strong>Aida</strong> – a valid concern.<br />

Pharaoh arrives and a messenger delivers news of Ethiopia’s invasion. With Thebes<br />

now under threat, Pharaoh and <strong>the</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>red assembly cry out for war. Radamès<br />

will lead <strong>the</strong>ir troops into battle and Amneris is elated. Radamès thanks <strong>the</strong> gods,<br />

confident of victory. He is led to <strong>the</strong> temple of Vulcan to be anointed. The powerful<br />

scene continues with <strong>the</strong> chorus of priests and citizens invoking <strong>the</strong>ir gods to bring<br />

victory to Egypt and death to <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians. Amneris presents Radamès with a<br />

staff that is blessed to ensure his victory.<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>, now alone, is filled with self-reproach for repeating <strong>the</strong> impious words calling<br />

for Egyptian victory. She is torn between her love for Radamès and her loyalty to<br />

Ethiopia. If <strong>the</strong> Egyptians are defeated and her fa<strong>the</strong>r rescues her from slavery,<br />

Radamès may die. If Radamès is victorious, her fa<strong>the</strong>r may be enslaved or killed<br />

and her country destroyed.<br />

6<br />

At <strong>the</strong> temple, priests chant hymns to <strong>the</strong>ir gods. Radamès receives <strong>the</strong><br />

consecrated armour and sword and now acts with <strong>the</strong> powers of <strong>the</strong> gods<br />

to protect and defend Egypt.<br />

ACT II<br />

Egypt is victorious against <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians. Amneris is prepared for<br />

<strong>the</strong> victory celebration by her attendants while she dreams of Radamès.<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> enters. Amneris is suspicious about her slave’s feelings, but does not yet<br />

know <strong>Aida</strong>’s true identity. At first, Amneris responds with genuine affection to<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>, but <strong>the</strong>n deliberately misleads her, telling her that Radamès died in battle.<br />

Hearing this, <strong>Aida</strong> cannot hide her despair. Amneris knows she has discovered <strong>the</strong><br />

truth. With complete guile, Amneris contradicts <strong>the</strong> news, telling her Radamès lives.<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> is elated, but having discovered her secret, Amneris declares herself <strong>Aida</strong>’s rival.<br />

The Grand March accompanies <strong>the</strong> entrance of Pharaoh and <strong>the</strong> court, and a ballet<br />

of celebration displays <strong>the</strong> treasures taken as <strong>the</strong> spoils of victory. During <strong>the</strong> Triumphal<br />

scene, Radamès is praised as Egypt’s saviour.<br />

As his reward, Radamès asks Pharaoh for mercy for <strong>the</strong> prisoners. One of <strong>the</strong> prisoners<br />

is Amonasro, King of Ethiopia and <strong>Aida</strong>’s fa<strong>the</strong>r, disguised as an officer. Recognizing<br />

him, <strong>Aida</strong> cries out “My fa<strong>the</strong>r!” When <strong>the</strong>y embrace, he tells her quietly not to reveal<br />

his true identity as king.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> high priest Ramfis and <strong>the</strong> priests are indignant to Radamès’ wish. They advise<br />

Pharaoh to sentence <strong>the</strong> prisoners to death for fear <strong>the</strong> captives will rise up and attack<br />

Egypt again. Radamès reminds Pharaoh of his promise to free <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians; he<br />

believes <strong>the</strong>ir king was killed in battle and <strong>the</strong> enemy has no hope of mounting ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

attack. Ramfis suggests a compromise: free <strong>the</strong> prisoners, keeping <strong>Aida</strong> and Amonasro<br />

as hostages. Pharaoh agrees and announces <strong>the</strong> marriage of Radamès to Amneris.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> grandiose finale, Amneris gloats at her triumph, <strong>Aida</strong> despairs, Radamès is<br />

tornand confused, and Amonasro, thinking his daughter is despondent at <strong>the</strong> thought<br />

of never being free, urges her to be patient. He is still unaware of his daughter’s<br />

love for Radamès.

Synopsis: Con't<br />

ACT III<br />

Amneris and Ramfis arrive at <strong>the</strong> temple to pray amid hymns for wedding preparations.<br />

Homesick for Ethiopia, <strong>Aida</strong> appears for a secret meeting with Radamès. Meanwhile,<br />

Amonasro has learned his daughter loves Radamès. Amonasro warns his daughter<br />

that Amneris will destroy her. Invoking patriotism, Amonasro tells <strong>Aida</strong> that she is<br />

obligated to help <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians defeat <strong>the</strong> Egyptians, promising she can have her<br />

country, her throne and Radamès. Amonasro manipulates his daughter, convincing<br />

her to learn Radamès’ tactical military secrets. When <strong>Aida</strong> refuses, Amonasro calls<br />

her a traitor to her people, unless she relents and betrays Radamès. <strong>Aida</strong> agrees.<br />

Radamès appears. <strong>Aida</strong> denounces him as Amneris’ husband, but Radamès swears<br />

he only loves <strong>Aida</strong>. She argues that <strong>the</strong> only solution is to flee to Ethiopia, describing<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir blissful life toge<strong>the</strong>r. Radamès hesitates; <strong>Aida</strong> renounces him and tells him to go<br />

to Amneris. Radamès refuses, deciding to flee with <strong>Aida</strong>. He reveals that <strong>the</strong> road along<br />

<strong>the</strong> gorges of Napata will be safe until tomorrow, when <strong>the</strong> Egyptian armies attack<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ethiopians at dawn. Amonasro, in hiding, hears this and reappears, announcing<br />

he is both <strong>the</strong> presumed-dead king and <strong>Aida</strong>’s fa<strong>the</strong>r. Upset, Radamès realizes he has<br />

betrayed his country.<br />

Amneris and Ramfis exit <strong>the</strong> temple, overhearing Radamès’ betrayal. They accuse him<br />

of treachery. Radamès prevents Amonasro’s attempt on Amneris’ life, and Amonasro<br />

and <strong>Aida</strong> flee. Guards appear and arrest Radamès.<br />

7<br />

ACT IV<br />

With Ethiopia defeated, <strong>Aida</strong> fears Radamès will be considered a traitor, condemned<br />

to die by <strong>the</strong> priests. Amneris decides if Radamès renounces <strong>Aida</strong>, she will use her<br />

power to persuade Pharaoh to pardon Radamès. Radamès, however, has accepted his<br />

fate. He believes <strong>Aida</strong> is dead and does not care about his own life. Amneris reveals<br />

that <strong>Aida</strong> lives and pleads with him to save his life by living for her. When Radamès<br />

refuses Amneris, she lapses into anger and intense frustration, only underscoring her<br />

defeat more. Radamès, oblivious, is led off to trial.<br />

The priests intone <strong>the</strong> charges against Radamès, who enters no plea for his life.<br />

He is sentenced to be buried alive. Amneris remains outside, cursing <strong>the</strong> priests<br />

and crying to <strong>the</strong> gods.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> crypt, Radamès is joined by <strong>Aida</strong>, who has elected to die with him. Their duet<br />

affirms <strong>the</strong>y believe <strong>the</strong>y will be immortalized in heaven. Above <strong>the</strong> tomb, Amneris<br />

prays for Radamès: “Pace, t’imploro, pace t’imploro, pace, pace, pace!” (“I pray for peace,<br />

I pray for peace!”)

The Story Behind <strong>the</strong> Story<br />

While it is popular belief that <strong>Aida</strong> was commissioned by <strong>the</strong> Khedive of Egypt<br />

to celebrate <strong>the</strong> opening of <strong>the</strong> Suez Canal in 1869, Verdi had in fact declined <strong>the</strong><br />

Khedive’s offer. As part of <strong>the</strong>se opening celebrations, an opera house in Cairo was<br />

also underway to be opened <strong>the</strong> same year. The Khedive of Egypt was an admirer of<br />

all things European and desired to commission an opera to commemorate <strong>the</strong> two<br />

openings. While Verdi resisted writing a special piece for <strong>the</strong> occasion, <strong>the</strong> house<br />

still opened with one of Verdi’s existing popular operas - Rigoletto.<br />

When Verdi learned from Camille du Locle (a director and librettist of Don Carlos)<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Khedive had decided to offer <strong>the</strong> commission of a dedicatory opera to ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

composer, he quickly changed his mind and undertook <strong>the</strong> challenge to write a unique<br />

opera for <strong>the</strong> Cairo house himself. Commissioned for <strong>the</strong> large sum of 150,000 francs,<br />

Verdi began composing in 1870. He wished to create a grand spectacle, akin to French<br />

grand opera, with scenes of splendour, a large orchestra and chorus.<br />

The Khedive had worked closely with French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette asked<br />

him to create a plot based on his historical research of ancient Egypt to be used for<br />

an opera. It was later reworked and expanded by Camille du Locle and presented as<br />

a synopsis to Verdi. The composer accepted <strong>the</strong> story and <strong>the</strong> libretto was written by<br />

Antonio Ghislanzoni. While <strong>the</strong> premiere was planned for January 1871, <strong>the</strong> outbreak<br />

of Franco-Prussian War in Europe left Auguste Mariette unable to leave Paris.<br />

Leaving him stranded with <strong>Aida</strong>’s costumes and sets, <strong>the</strong> premiere was forced to<br />

be delayed until December.<br />

When <strong>Aida</strong> premiered December 1871 at <strong>the</strong> Khedival <strong>Opera</strong> House, it was met<br />

with great acclaim. Verdi was not in attendance, and a year later in 1872 <strong>Aida</strong> made<br />

its European debut at <strong>the</strong> famous La Scala Theatre in Milan.<br />

8<br />

Following <strong>the</strong> opening of <strong>Aida</strong>, it quickly became popular throughout Italy and<br />

expanded worldwide opening in NYC in 1873, and in Paris and London in 1876.<br />

It remains one of <strong>the</strong> most performed operas today; ranking among <strong>the</strong> top 20<br />

most frequently performed operas throughout <strong>the</strong> world.

Europe at <strong>the</strong> Time of <strong>Aida</strong><br />

During <strong>the</strong> time <strong>Aida</strong> was written, Europe was facing great political change. In 1870<br />

France under Napoleon III declared war on <strong>the</strong> German Kingdom of Prussia, but was<br />

defeated and as a result lost <strong>the</strong> regions of Alsace and Lorraine. Prussia was aided by<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r German states and <strong>the</strong> victory led to <strong>the</strong> unification of <strong>the</strong> German Empire<br />

under King William I of Prussia. In Italy, nationalists fought to unify <strong>the</strong> country –<br />

even Verdi and <strong>Aida</strong> librettist Antonio Ghislanzoni were involved in <strong>the</strong> political<br />

change culminating in <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

Verdi often reflected <strong>the</strong> political turbulence of <strong>the</strong> time in his operas and became<br />

known as <strong>the</strong> “Composer of <strong>the</strong> Revolution” after Nabucco premiered in 1842.<br />

This opera portrayed <strong>the</strong> Hebrew people oppressed by <strong>the</strong> tyranny of <strong>the</strong> Babylonians.<br />

This plot which resonated and even caused chaos with <strong>the</strong> Italian audiences of <strong>the</strong><br />

time was considered to be replete with political overtones, paralleling its story to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Austrian control over <strong>the</strong>ir country.<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> is no exception; in this opera Verdi continued to present <strong>the</strong>mes of political<br />

instability as shown through Radamès and <strong>Aida</strong> who must choose between <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

patriotic duties versus eternal happiness through love. In <strong>the</strong> face of love for one’s<br />

country and love for <strong>the</strong> enemy, a feasible solution seems impossible. Verdi creates<br />

dramatic tension throughout <strong>the</strong> opera by making his characters face <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

conflicting loyalties.<br />

9

Piecing Toge<strong>the</strong>r an Ancient World<br />

French Archeologist and Egyptologist Auguste Mariette was hired by <strong>the</strong> Khedive<br />

of Egypt to create a plot based on his historical findings for Verdi. With his expertise<br />

he was also involved in <strong>the</strong> design of <strong>the</strong> costumes and sets for its premiere in 1871.<br />

Mariette studied how ancient Egyptians lived from paintings to architecture,<br />

to create au<strong>the</strong>ntic scenery and costumes depicting <strong>the</strong>se ancient times.<br />

Frequently, productions of <strong>Aida</strong> today reference traditional ancient Egypt set during<br />

<strong>the</strong> Dynasty of <strong>the</strong> Pharaohs particularly in Memphis and Thebes. Visuals on set<br />

portray <strong>the</strong> grandiosity of Pharaohs, recognizable symbols such as <strong>the</strong> Pyramids<br />

of Giza, <strong>the</strong> Great Sphinx as well as ornate gold costumes.<br />

The history of ancient Egypt is divided into dynasties which mark <strong>the</strong> succession<br />

of Egyptian rulers. Knowledge of <strong>the</strong>se periods is based on kinglists recorded by<br />

Egyptians <strong>the</strong>mselves that have been preserved in carvings such as <strong>the</strong> famous<br />

Palermo Stone and Abydos Kinglist (carved on <strong>the</strong> temple), and writings on papyrus<br />

like <strong>the</strong> Turin Canon. An Egyptian historian and priest in <strong>the</strong> temple of Heliopolis<br />

named Manetho wrote History of Egypt (or Aegyptiaca) in <strong>the</strong> third century bc<br />

This work, in which he organized <strong>the</strong> kings into <strong>the</strong> thirty dynasties, is evidence<br />

of <strong>the</strong> reign of pharaohs. These records combine to provide archeologists with<br />

fragmented answers that help structure <strong>the</strong> history into <strong>the</strong> series of kingdoms<br />

and periods we know as ancient Egypt.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r Learning<br />

• Visit Discovery Channel online dsc.discovery.com/egypt/ for video<br />

clips about ancient Egypt.<br />

• National Geographic.com also provides many great photos of ancient<br />

and modern day Egypt.<br />

10

Kings, Pharaohs and Queens of Egypt<br />

Ancient Egyptian kings were <strong>the</strong> leaders and preservers of peaceful and stable society.<br />

From performing religious rituals to seeing to economic needs, <strong>the</strong> king was deemed<br />

as protector of <strong>the</strong> country. It was believed that <strong>the</strong> god Horus was connected to living<br />

kings, while <strong>the</strong> god Osiris was associated with dead kings. Even though <strong>the</strong> kings were<br />

linked to <strong>the</strong> gods, ancient rituals show that <strong>the</strong> ancient Egyptians were aware of <strong>the</strong><br />

mortality of <strong>the</strong>ir kings.<br />

While kingship ideally passed on from fa<strong>the</strong>r to son, queens were also very significant<br />

to society. The mo<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> king served as a symbol of rebirth and creation- giving<br />

her great importance and power. One great female royal, regarded as on of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

successful leaders by Egyptologists, was queen Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut reigned during<br />

<strong>the</strong> 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt and is known for establishing prosperous trade<br />

networks during <strong>the</strong> dynasty and commissioning hundreds of buildings in Upper and<br />

Lower Egypt.<br />

The word ‘pharaoh’ was a title used by <strong>the</strong> ancient Egyptians to refer to <strong>the</strong> king.<br />

Stemming from <strong>the</strong> ancient Egyptian term per-aa meaning ‘Big House’, it was first<br />

used in reference to <strong>the</strong> royal estate. It was later used to describe <strong>the</strong> king himself in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 18 th dynasty of <strong>the</strong> New Kingdom.<br />

11

Composer<br />

Giuseppe Verdi<br />

Giuseppe Verdi was born in 1813 in <strong>the</strong> small Italian village of Le Roncole. His family<br />

was of middle class origin consisting of landowners, and his fa<strong>the</strong>r was very supportive<br />

of his son’s education and career aspirations. At a young age Verdi began assisting <strong>the</strong><br />

local church organist and later in high school studied humanities and had formal music<br />

lessons. He received financial support and encouragement from <strong>the</strong> wealthy Antonio<br />

Barezzi, and applied to study at <strong>the</strong> Milan Conservatory in 1832. Verdi was refused<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Conservatory and instead began studying under Vincenzo Lavigna, a former<br />

musician and conductor at <strong>the</strong> famous La Scala <strong>Opera</strong> House in Milan. In 1836 after<br />

completing his studies, Verdi returned to Busseto and married Margherita Barezzi<br />

(Antonio’s daughter). He composed and conducted with Busseto Philharmonic<br />

Society during <strong>the</strong> next few years.<br />

In 1839 Verdi wrote his first opera, Oberto, which premiered at La Scala in Milan<br />

and was well received. Shortly after, however Verdi’s family was hit by tragedy.<br />

Within a short period of time his wife and two young children died. Verdi nearly<br />

abandoned composing, but with <strong>the</strong> encouragement of his colleagues he continued<br />

writing. Inspired by a story, he began writing again and was met with <strong>the</strong> great success<br />

of his opera Nabucco when it premiered in 1842. Over <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> next eleven<br />

years, from 1842-1853, Verdi composed a series of sixteen operas. During this period<br />

known as his “galley years”, Verdi created famous works including Rigoletto (1851),<br />

Il Trovatore (1853), and La Traviata (1853) that remain remarkable pieces of opera<br />

history today. Achieving great successes with his work, Verdi became world renowned<br />

as <strong>the</strong> leading Italian opera composer.<br />

With his successes Verdi gained greater freedom in his artistry and spent more time<br />

away from <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre and work. After ten years toge<strong>the</strong>r he married <strong>the</strong> soprano<br />

Giuseppina Strepponi in 1859 and settled near Busseto. Verdi became involved in <strong>the</strong><br />

political activity of <strong>the</strong> time as a member of <strong>the</strong> newly-formed national parliament and<br />

ultimately was appointed to <strong>the</strong> senate. He took his duties as a senator very seriously,<br />

12<br />

V Verdi<br />

V Verdi<br />

taking copious notes and logged one of <strong>the</strong> highest attendances and voting records at<br />

that time in Italy’s parliamentary history. With his fame and success Verdi was able to<br />

be more selective over commissions offered to him. He wrote six new operas after<br />

La Traviata including <strong>the</strong> popular pieces Don Carlos in 1867 and <strong>Aida</strong> in 1871.<br />

The following years Verdi composed Otello (1887) and his last opera Falstaff (1893),<br />

both based on two Shakespeare plays (O<strong>the</strong>llo and The Merry Wives of Windsor,<br />

respectively). They premiered with resounding success and became internationally<br />

popular. In 1894 he composed a ballet for Otello and his last composition was written in<br />

1897. In 1901 at <strong>the</strong> age of eighty-seven Verdi had a stroke while in Milan and passed<br />

away a few days later. Orchestras and musicians came from every corner of Italy for his<br />

funeral in Milan. With 28,000 people lining <strong>the</strong> streets, his funeral remains <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

public assembly in Italy’s history. Verdi was one of <strong>the</strong> most influential composers of<br />

<strong>the</strong> 19 th century writing 28 operas in all, and it is impossible not to find a work by<br />

Verdi being performed somewhere in <strong>the</strong> world as you are reading <strong>the</strong>se words!

Librettist<br />

Antonio Ghislanzoni<br />

Ghislanzoni was born in 1824 in <strong>the</strong> town of Lecco, Italy. When he was young he<br />

briefly studied in a seminary and <strong>the</strong>n medicine, but left to pursue his interest in music<br />

and writing. Inspired by <strong>the</strong> nationalist ideas of <strong>the</strong> unification of Italy he founded<br />

several newspapers in Milan during <strong>the</strong> late 1840s. His involvement in helping <strong>the</strong><br />

new republic resulted in him being arrested and detained by <strong>the</strong> French. During <strong>the</strong><br />

1850s Ghislanzoni was an active journalist and editor among <strong>the</strong> bohemians of Milan.<br />

In 1869 he decided to return to his hometown and retire from journalism. He began<br />

writing libretti for operas and also wrote several short stories and novels. Among<br />

eighty-five libretti written, his best known work remains <strong>Aida</strong>.<br />

Story by<br />

Auguste Mariette<br />

Mariette was born in 1821 in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn city of Boulogne-sur-Mer in France. He<br />

was a talented draftsman, designer, teacher and writer of historical and archaeological<br />

topics. When his cousin passed away, Mariette organized his papers and was inspired<br />

by his work on Egyptology. He began studying hieroglyphics and <strong>the</strong> ancient Egyptian<br />

language Coptic, which led him to a minor appointment at <strong>the</strong> Louvre Museum in<br />

Paris in 1849. In 1850, assigned by <strong>the</strong> French government, he made his first trip<br />

to Egypt with <strong>the</strong> goal of purchasing ancient manuscripts for <strong>the</strong> Louvre collection.<br />

With little success finding manuscripts, Mariette prolonged an embarrassing return to<br />

France by visiting temples and befriending a Bedouin tribe. The tribe led him to <strong>the</strong><br />

site of <strong>the</strong> ancient Egyptian burial ground Saqqara, which at first Mariette believed to<br />

be merely mounds of sand. After noticing a sphinx, he assembled several workmen to<br />

begin <strong>the</strong> excavation. In 1851 <strong>the</strong> discovery of <strong>the</strong> reputed avenue of <strong>the</strong> sphinxes was<br />

13<br />

made and later <strong>the</strong> underground catacomb of tombs with statues and tablets among<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r treasures. France funded Mariette’s continued research and he remained in Egypt<br />

to ship new discoveries to <strong>the</strong> Louvre. Egyptian authorities were not pleased, and <strong>the</strong><br />

French agreed to divide findings equally with Egypt.<br />

While he worked briefly as an assistant conservator at <strong>the</strong> Louvre, he soon returned to<br />

Egypt to work for <strong>the</strong> Egyptian government as conservator under <strong>the</strong> Khedive Isma’il<br />

Pasha. During this time he made several ground-breaking discoveries and excavations<br />

including <strong>the</strong> Pyramid fields of Memphis, <strong>the</strong> catacombs of Meidum, Abydos, and<br />

Thebes, <strong>the</strong> Temples of Dendera and Edfu, and <strong>the</strong> Temple of <strong>the</strong> Sphinx. He also<br />

received funding to create Bula Museum in Cairo to house many of <strong>the</strong> antiquities<br />

and reduce <strong>the</strong> illicit trade of artifacts. Even though Mariette’s relationship with <strong>the</strong><br />

Egyptian Khedive was not always stable, o<strong>the</strong>r rival country’s Egyptologists, such as<br />

those from Britain and Germany, were restricted from digging in Egypt.<br />

In 1869 <strong>the</strong> Khedive requested Mariette to write a short plot for an opera. The<br />

following year Camille du Locle, a French librettist and <strong>the</strong>atre director, worked <strong>the</strong><br />

plot into a scenario, which was presented to Verdi to use in <strong>Aida</strong>. The scenery and<br />

costumes for <strong>the</strong> opera were inspired by Ancient Egypt and overseen by Mariette and<br />

Du Locle. While <strong>the</strong> premiere was scheduled for January 1871, it was delayed until<br />

December because of <strong>the</strong> Franco-Prussian War. Mariette who was responsible for <strong>the</strong><br />

scenery and costumes was unable to leave Paris due to its siege. When <strong>Aida</strong> opened<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Khedival <strong>Opera</strong> House in Cairo it was met with great success and Mariette<br />

received several honours from Egyptian and European authorities.

Glossary<br />

Arias: Meaning “air” in Italian. Arias are solos that<br />

accompany <strong>the</strong> orchestra, which allow a character<br />

to express <strong>the</strong>ir feelings and demonstrate <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

vocal talents.<br />

Baritone: A type of male voice that is lower than<br />

<strong>the</strong> tenor, but higher than <strong>the</strong> bass. Usually played<br />

by fa<strong>the</strong>r figures or middle-aged children.<br />

Bass: A type of male voice that is <strong>the</strong> lowest pitched.<br />

It is often played by wise and older characters.<br />

Chorus: A large group of singers, often 40 or more,<br />

who appear on stage in a crowd scene. Sometimes<br />

<strong>the</strong> chorus comments on action or contrasts solos.<br />

Composer: Writes <strong>the</strong> music.<br />

Contralto: A type of female voice that is <strong>the</strong> lowest<br />

pitched. Their voice is deep and well-rounded.<br />

Usually played by <strong>the</strong> maid, mo<strong>the</strong>r or grandmo<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Coptic Egyptian: an Egyptian language spoken until <strong>the</strong><br />

17th Century. It is now considered extinct because <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are no native speakers of <strong>the</strong> language.<br />

Ensemble: A musical number sung by two or more<br />

people of different ranges. For example, duets, trios,<br />

quartets, quintets and sextets.<br />

Gallery Years: <strong>the</strong> middle period of Verdi's career from<br />

1842–1853 where he composed a series of sixteen<br />

demanding operas. Beginning with <strong>the</strong> premiere of<br />

Nabucco and ending shortly after La Traviata.<br />

Khedive: title used in Egypt until 1914 meaning 'lord'<br />

or 'ruler' in Persian.<br />

Librettist: Chooses a story, writes or adapts <strong>the</strong> words.<br />

Mezzo Soprano: A type of female voice that is lower<br />

than <strong>the</strong> soprano and higher than <strong>the</strong> contralto.<br />

Often played by <strong>the</strong> character of <strong>the</strong> young boy,<br />

a complex or evil character.<br />

Playwright: Someone who writes plays.<br />

Pharaoh: title meaning 'king' in Egypt during <strong>the</strong><br />

New Kingdom, specifically in <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> 18th<br />

dynasty.<br />

Saqqara: an ancient burial site in Memphis, Egypt<br />

where several famous pyramids are located such as <strong>the</strong><br />

Step Pyramid of Djoser.<br />

14<br />

Soprano: Highest pitched female voice. Usually <strong>the</strong><br />

female lead singer is written as this type of voice.<br />

There are 3 types: coloratura, dramatic, and lyric.<br />

Sphinx: a mythical creature, often found in Greek<br />

mythology and Egyptian architecture, which is<br />

recognized by its human or cat-like head and lion body.<br />

Suez Canal: a man-made waterway in Egypt that<br />

connects <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean and Red Seas. It opened in<br />

1869 and allows travel between Europe and Asia while<br />

bypassing Africa.<br />

Teatro all Scala: also known as La Scala – was meant to<br />

imply that it was '<strong>the</strong> scale of measurement for <strong>the</strong> best<br />

singing in Italy. It is a renowned oepra house in Milan,<br />

Italy dating from 1778.<br />

Tenor: A type of male voice that is <strong>the</strong> highest pitched.<br />

It is often <strong>the</strong> leading role and <strong>the</strong>y typically fall in love<br />

with Sopranos.<br />

Thebes: Ancient Egyptian city on <strong>the</strong> east bank of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Nile. Its ruins are located in <strong>the</strong> modern day city<br />

of Luxo, Egypt. It is a designated UNESCO World<br />

Heritage Site.

Activity 1:<br />

Listening Guide (1/6)<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

Music: Grades 4-6 Listening and Expression<br />

Grades 7-9 Valuing and Listening<br />

Grades 10-12 Theory: Elements and Structures<br />

Activity<br />

This activity will encourage students to listen to musical clips from <strong>Aida</strong> and<br />

learn how to interpret and make an informed opinion about what <strong>the</strong>y hear.<br />

Before listening, introduce <strong>the</strong> Synopsis, Characters and The Story Behind<br />

<strong>the</strong> Story to give context to <strong>the</strong> music.<br />

Listening Guide written by Stephan Bonfield<br />

Track # Musical Excerpt Connection to <strong>the</strong> Story Musical Elements of Significance Strategies for Listening<br />

1<br />

Act 1, scene 1: Memphis:<br />

Radames - “Celeste <strong>Aida</strong>,<br />

forma divina” (“Heavenly<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>, divine form”)<br />

Radames, selected by <strong>the</strong><br />

goddess Isis to command<br />

<strong>the</strong> armies against <strong>the</strong><br />

Ethiopians, sings of his<br />

love for <strong>Aida</strong>.<br />

He dreams of triumph in<br />

battle, of Pharaoh granting<br />

him <strong>the</strong> victory prize of<br />

his choice, which he would<br />

use to make his beloved<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> free.<br />

15<br />

This is a ‘romanza’ and is one of <strong>the</strong> most famous<br />

arias Verdi composed for <strong>the</strong> tenor voice. It is set<br />

in A-B-A form.<br />

The middle section sounds a little more agitated as<br />

Radames resolves to show <strong>Aida</strong> <strong>the</strong> blue skies of her<br />

homeland once again.<br />

The strings play numerous effects that remind <strong>the</strong><br />

listener of <strong>the</strong> heavens, <strong>the</strong> sun, and o<strong>the</strong>r naturalistic<br />

comparisons Radames draws from nature to relate to<br />

his ‘heavenly’ <strong>Aida</strong>.<br />

How does <strong>the</strong> aria show<br />

Radames dreams of love<br />

for <strong>Aida</strong>, despite <strong>the</strong><br />

impossible situation <strong>the</strong><br />

lovers find <strong>the</strong>mselves in?<br />

The ending of this aria<br />

is considered one of <strong>the</strong><br />

most difficult in opera<br />

history. Why?

Listening Guide (2/6)<br />

Track # Musical Excerpt Connection to <strong>the</strong> Story Musical Elements of Significance Strategies for Listening<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Act 1, scene 1:<br />

Trio - Amneris, <strong>Aida</strong>,<br />

Radames: “Dessa!”<br />

Act 1, scene 1:<br />

All - "Su! del Nilo”<br />

(“Arise! From our<br />

sacred Nile”)<br />

Amneris observes<br />

Radames trying to conceal his glances<br />

toward <strong>Aida</strong>.Radames worries that<br />

Amneris may have discovered his love<br />

for <strong>Aida</strong>. Amneris suspects that <strong>Aida</strong> is,<br />

Radames’ love. <strong>Aida</strong> despairs that she<br />

will never see Radames or her homeland<br />

again.<br />

A messenger announces Ethiopia's<br />

invasion of Egypt. With Thebes now<br />

under threat, Pharaoh declares war,<br />

and all cry out <strong>the</strong> words “Guerra, guerra”<br />

(“War, war”). Pharaoh announces that<br />

Radames will lead <strong>the</strong>ir troops into battle.<br />

Amneris is elated. Radames thanks <strong>the</strong><br />

gods and is confident of victory, however<br />

Aïda is more fearful now than ever that<br />

she will lose Radames. Radames is led<br />

to <strong>the</strong> temple of Vulcan to be anointed<br />

as <strong>the</strong> chorus of priests and citizens sing<br />

"Su! del Nilo” (“Arise! From our sacred<br />

Nile”) invoking <strong>the</strong>ir gods to bring victory<br />

to Egypt. Amneris presents Radames with<br />

a staff that is blessed to ensure his victory,<br />

and all sing <strong>the</strong> final chorus “Ritorna<br />

vincitor” ("Return victorious”).<br />

16<br />

In this trio, Verdi skillfully manages to show<br />

<strong>the</strong> separate emotions of <strong>the</strong> three singers by<br />

writing three very different lines, interweaving<br />

with one ano<strong>the</strong>r. Here, Verdi wastes no time<br />

exposing <strong>the</strong> central plot vehicle - <strong>the</strong> love<br />

triangle, and its difficult situation for <strong>the</strong><br />

lovers Radames and <strong>Aida</strong>.<br />

This is some of Verdi’s most stirring music.<br />

The architecture of <strong>the</strong> many choral pieces,<br />

interspersed with ensemble singing, is what<br />

makes this scene so famous. Here, Verdi<br />

shows how well he can depict so many<br />

emotions from different characters at<br />

<strong>the</strong> same time.<br />

How does Verdi use<br />

<strong>the</strong> music to show <strong>the</strong><br />

more personal aspects<br />

of <strong>the</strong> opera?<br />

Watch a video of this scene<br />

carefully. How does staging<br />

help to explain <strong>the</strong> plot and<br />

<strong>the</strong> dynamic between <strong>the</strong><br />

characters? (i.e., potential<br />

rivalry between princess<br />

and slave, lover and<br />

beloved, secret lover<br />

and beloved).<br />

What is <strong>the</strong> effect of<br />

this scene? How does it<br />

illustrate <strong>the</strong> expectations<br />

of <strong>the</strong> characters on stage<br />

for what outcome <strong>the</strong>y<br />

hope will occur after <strong>the</strong><br />

battle against Ethiopia?

Listening Guide (3/6)<br />

Track # Musical Excerpt Connection to <strong>the</strong> Story Musical Elements of Significance Strategies for Listening<br />

4<br />

5<br />

Act 1, scene 1:<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>: “Ritorna vincitor,<br />

L’insana parola” ("Return<br />

victorious, <strong>the</strong> insane<br />

words!”).<br />

Act 1, scene 2:<br />

The Temple of Vulcan:<br />

Priests - “Possente Ftha:”<br />

(“Powerful Phta”)<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> chastises herself for repeating <strong>the</strong><br />

victory cry of <strong>the</strong> Egyptians, against her<br />

native Ethiopia, but she is forced to do<br />

so under public pressure.<br />

She laments her capture, her desperate<br />

situation, <strong>the</strong> fact that she is a princess<br />

to Ethiopia, and that should her fa<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

King Amonasro, be victorious, it would<br />

mean <strong>the</strong> loss of her beloved Radames.<br />

Here, <strong>the</strong> Egyptian ritual is performed<br />

that consecrates Radames as sacred<br />

defender of Egypt.<br />

17<br />

This is a multi-sectional arioso, depicting different<br />

and often contrasting emotions that highlight <strong>Aida</strong>’s<br />

confused emotional state.<br />

This is a complex tableau in grand French<br />

operatic style, featuring a high priestess,<br />

<strong>the</strong> high priest Ramfis, a chorus of priests<br />

and a ballet. This scene depicts <strong>the</strong> sacred<br />

rite for preparation of battle.<br />

The tableau concludes with <strong>the</strong> concertato<br />

“Nume, custode e vindice” (“Gods, guide<br />

and bring to victory”).<br />

Describe <strong>the</strong> central<br />

emotional conflict of each<br />

section within <strong>Aida</strong>’s arioso.<br />

Discuss how Verdi changes<br />

<strong>the</strong> music with each<br />

section. How does each<br />

section depict different<br />

states of <strong>Aida</strong>’s conflicted<br />

mind?<br />

Describe <strong>the</strong> many<br />

musical and staging<br />

devices of <strong>the</strong> scene.<br />

What kinds of sounds<br />

does Verdi add to make<br />

<strong>the</strong> ritual seemingly<br />

sound au<strong>the</strong>ntically<br />

ancient Egyptian?

Listening Guide (4/6)<br />

Track # Musical Excerpt Connection to <strong>the</strong> Story Musical Elements of Significance Strategies for Listening<br />

6<br />

Act 2, scene 1:<br />

In Amneris’ apartments:<br />

Amneris -<br />

“Ah! vieni, vieni amor mio”<br />

("Come, come my love").<br />

– ballet – Amore, amore!<br />

– “Trema, vil’ schiava”<br />

(Tremble, vile slave”)<br />

Amneris begins by singing of her love<br />

for Radames and his victory, and how<br />

she hopes he will soon be hers. When<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> enters, she renews her suspicions<br />

that her slave is her rival, and deceives<br />

her by telling <strong>Aida</strong> that Radames died<br />

in battle. When <strong>Aida</strong> is disconsolate,<br />

and Amneris reverses her earlier words,<br />

stating in fact that Radames lives, <strong>Aida</strong><br />

is elated, and gives herself away by here<br />

reactions. Amneris tells her to “Trema,<br />

vil’ schiava” (Tremble, vile slave”) and<br />

that she is <strong>Aida</strong>’s rival for Radames.<br />

18<br />

The scene opens with Amneris’ slaves waiting on her,<br />

singing of <strong>the</strong>ir devotion to Amneris. The female<br />

chorus is punctuated by Amneris’ dreams of Radames,<br />

symbolized by her high note to begin each phrase.<br />

When <strong>Aida</strong> appears, <strong>the</strong> music sounds innocent<br />

enough, depicting Ameris’ pretense of sympathy for<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>’s situation. However, <strong>the</strong> music soon becomes<br />

tense as Amneris draws out <strong>Aida</strong> with each moment.<br />

Amneris sings in chromatic meanders, attempting to<br />

trap <strong>Aida</strong> so that she will reveal her love for Radames.<br />

Verdi beautifully illustrates <strong>Aida</strong>’s roller-coaster ride of<br />

emotion as she learns from Amneris that Radames first<br />

has died, but actually lives. Then Amneris unleashes<br />

her full wrath, declaring herself to be <strong>Aida</strong>’s rival.<br />

When offstage trumpets declare <strong>the</strong> triumphant return<br />

of <strong>the</strong> army, Amneris sings with <strong>the</strong>m, while <strong>Aida</strong><br />

answers in <strong>the</strong> mnor mode, in despair. Left alone,<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> sings for <strong>the</strong> gods to have mercy (“Numi pieta”).<br />

What do you think of<br />

Amneris’ behavior in this<br />

scene? Can you explain<br />

Amneris’ behavior from<br />

two possible perspectives –<br />

hers and <strong>Aida</strong>’s? Make use<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se two differing sides<br />

for your discussion.<br />

How does <strong>the</strong> conflict<br />

between <strong>the</strong> two princesses<br />

represent what is stake<br />

for both Egypt (power of<br />

succession) and Ethiopia<br />

(freedom)?

Listening Guide (5/6)<br />

Track # Musical Excerpt Connection to <strong>the</strong> Story Musical Elements of Significance Strategies for Listening<br />

7<br />

8<br />

Act 2, scene 2: Thebes:<br />

All -“Gloria all’Egitto”<br />

(“Glory to Egypt”)<br />

Act 3:<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> -“O patria mia!”<br />

(“Oh my country”).<br />

In this impressive finale to Act II,<br />

<strong>the</strong> victorious Egyptians hold a grand<br />

procession in front of <strong>the</strong> city gates,<br />

displaying <strong>the</strong> spoils of <strong>the</strong>ir triumphant<br />

battle. The prisoners are brought in,<br />

and beg for mercy. Radames asks for<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir release, <strong>the</strong> priests object, but<br />

Radames successfully convinces <strong>the</strong><br />

king to let <strong>the</strong>m go free. Amneris is<br />

presented to Radames as his bride-to-be.<br />

Dramatically, Verdi saves <strong>the</strong> introduction<br />

of <strong>Aida</strong>’s fa<strong>the</strong>r for this moment, but it is<br />

not yet revealed to <strong>the</strong> Egyptians that he<br />

is, in fact, king of Ethiopia.<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> has arrived for a secret meeting<br />

with Radames, at which she hopes to<br />

compel Radames to run away with<br />

her. Amonasro plays upon <strong>Aida</strong>’s<br />

nationalistic feelings, and reminds<br />

her of <strong>the</strong> atrocities committed by <strong>the</strong><br />

Egyptians on her people. He forces her<br />

to agree to extract Radames’ knowledge<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Egyptian armies’ location, so that<br />

king Amonasro and <strong>the</strong> Ethiopian army<br />

can mount ano<strong>the</strong>r attack.<br />

19<br />

The finale to Act II is a grand concertato, and<br />

consists of a grand march, a ballet, a prayer for<br />

mercy by <strong>the</strong> Ethiopian prisoners, and a final<br />

reprise of <strong>the</strong> opening “Gloria all’Egitto,” in which<br />

all sing of <strong>the</strong>ir reactions to <strong>the</strong> new situation.<br />

This scene features some splendid instrumental<br />

moments, particularly <strong>the</strong> on-stage use of trumpet<br />

fanfares. Again, Verdi interweaves multiple thoughts<br />

occurring simultaneously among <strong>the</strong> characters on<br />

stage, all set against a stirring choral backdrop.<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> is at her lowest, and most broken in this act.<br />

Not only is she suffering over <strong>the</strong> loss of Radames<br />

to her rival, but of her homeland too. This is<br />

evocatively demonstrated in her aria where she<br />

sings using a technique called coloratura, describing<br />

<strong>the</strong> scenic beauty of her country, with a sentimental<br />

and sympa<strong>the</strong>tic oboe line to accompany her.<br />

Soon Amonasro arrives; <strong>the</strong> orchestral colour<br />

eventually darkens via gradual changes as he<br />

manipulates his daughter more to his own ends.<br />

This scene is considered<br />

<strong>the</strong> grandest spectacle<br />

in <strong>the</strong> history of opera.<br />

How does Verdi use <strong>the</strong><br />

music to enhance <strong>the</strong><br />

magnificent staging?<br />

Do a web search of o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

productions. Have o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

productions used live<br />

animals? Can such a largescale<br />

finale be produced for<br />

a small stage?<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> seems to be in an<br />

impossible situation at<br />

this point in <strong>the</strong> opera.<br />

Can you suggest ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

situation, personal, or<br />

historical, in which<br />

someone may have been<br />

in a similar situation,<br />

where it seems that no<br />

matter what decision<br />

one makes, it seems<br />

impossible to win?<br />

What do you think of how<br />

Amonasro manipulated<br />

his daughter to extract <strong>the</strong><br />

secret route of <strong>the</strong> Egyptian<br />

army from Radames?

Listening Guide (6/6)<br />

Track # Musical Excerpt Connection to <strong>the</strong> Story Musical Elements of Significance Strategies for Listening<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Act 3: Banks of <strong>the</strong> Nile:<br />

Trio:Radames, <strong>Aida</strong>,<br />

Amonasro“Tu!...<br />

Amonasro! –<br />

io son disonorato!”<br />

(“You! Amonasro!<br />

I am dishonoured!”)<br />

Act 4, scene 2:<br />

The temple of Vulcan: a<br />

tomb below and temple<br />

above <strong>the</strong> vault:<br />

Radames and <strong>Aida</strong> are<br />

below, Amneris above.<br />

(“O terra addio”; "O earth,<br />

farewell").<br />

Radames has decided to flee all he has<br />

with <strong>Aida</strong>. When asked by which road<br />

<strong>the</strong>y can escape, Radames accidentally<br />

reveals that <strong>the</strong>ir escape route will<br />

be safe because <strong>the</strong> Egyptian armies<br />

won't attack <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians <strong>the</strong>re until<br />

dawn. Amonasro overhears this and<br />

announces he is <strong>the</strong> presumed-dead<br />

king of <strong>the</strong> Ethiopians and <strong>Aida</strong>'s fa<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Radames realizes he has just betrayed his<br />

country. Amneris and Ramfis overheard<br />

Radames' betrayal as <strong>the</strong>y exited <strong>the</strong><br />

temple and now accuse him of treachery.<br />

The act ends at <strong>the</strong> highest tensionpoint<br />

in <strong>the</strong> opera when Amonasro<br />

tries to assassinate Princess Amneris<br />

but is prevented by Radames, who gives<br />

himself up to <strong>the</strong> priests. Radames is<br />

arrested and taken away for judgment.<br />

Radames’ tomb is sealed, and he believes<br />

he shall never see <strong>Aida</strong> again. However<br />

<strong>Aida</strong> suddenly appears; she has chosen<br />

to die with him. The lovers believe that<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir love for each o<strong>the</strong>r will immortalize<br />

<strong>the</strong>m in heaven, and <strong>the</strong>y will live in<br />

eternal bliss.<br />

Above <strong>the</strong> tomb, Amneris prays her final<br />

words for Radames: “Pace t’imploro,<br />

pace t’imploro, pace, pace, pace!”<br />

(“I pray for peace, I pray for peace!”)<br />

20<br />

The finale to Act II is a grand concertato,<br />

and consists of a grand march, a ballet, a prayer<br />

for mercy by <strong>the</strong> Ethiopian prisoners, and a final<br />

reprise of <strong>the</strong> opening “Gloria all’Egitto,” in which<br />

all sing of <strong>the</strong>ir reactions to <strong>the</strong> new situation.<br />

This scene features some splendid instrumental<br />

moments, particularly <strong>the</strong> on-stage use of trumpet<br />

fanfares. Again, Verdi interweaves multiple thoughts<br />

occurring simultaneously among <strong>the</strong> characters on<br />

stage, all set against a stirring choral backdrop.<br />

Radames and <strong>Aida</strong> sing one of <strong>the</strong> most poignant<br />

love duets in opera history. It is difficult to act this<br />

duet, given that <strong>the</strong> singers must depict <strong>the</strong> air supply<br />

running out in <strong>the</strong> sealed vault, and must make <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

actions seems as convincing as possible. Verdi writes<br />

some of his most tranquil and poignant music to<br />

depict this death scene: chanting from above, a lyrical<br />

and mildly angular melodic arch, as though <strong>the</strong> lovers<br />

are singing <strong>the</strong>mselves to heaven, all covered with a<br />

shimmering harmonic glow in <strong>the</strong> orchestra.<br />

How would you judge<br />

Radames’ conduct in<br />

this scene? What has<br />

he done wrong?<br />

Is Radames innocent or<br />

guilty of treason?<br />

How would you assess<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>’s actions and feelings<br />

in this act?<br />

In <strong>the</strong> next act, Radames<br />

doesn’t defend himself in<br />

front of <strong>the</strong> priests for his<br />

treachery. Why?<br />

What do you think<br />

of how Verdi ended<br />

<strong>the</strong> opera?<br />

What do you think of<br />

<strong>the</strong> manner of death <strong>the</strong><br />

composer and librettist<br />

chose for <strong>the</strong> lovers?<br />

Would you have ended<br />

<strong>the</strong> opera differently?<br />

If so, how?

Activity 2:<br />

Nationalism & Identity<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

Social Studies Grades 11–20–1 Understandings of Nationalism<br />

Student Objectives<br />

Students will explore <strong>the</strong> influence of nationalism on one’s identity and resulting personal<br />

choices. Using <strong>the</strong> readings found in Your Guide to <strong>Aida</strong> discuss as a class <strong>the</strong> meaning of<br />

nationalism and its significance in <strong>the</strong> opera <strong>Aida</strong>.<br />

Activity<br />

Divide your class into two groups and give each an opposing perspective from below:<br />

• Personal love versus love for your country<br />

• National goals versus personal gain<br />

Each group will discuss amongst <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>the</strong> different beliefs and values from <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

given perspective. Encourage students to create a list and also think about possible<br />

rebuttals from <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r group. Use <strong>the</strong> following questions to prompt discussion if<br />

needed.<br />

Questions for Discussion<br />

What does it means for Radamès to betray his country?<br />

What pressures does <strong>Aida</strong> face from her fa<strong>the</strong>r Amonsasro?<br />

What influence do <strong>the</strong> gods have on <strong>the</strong> identities of <strong>Aida</strong> and Radamès?<br />

If <strong>Aida</strong> and Radamès lived in modern Canadian society, how would society’s view of<br />

<strong>the</strong>m change?<br />

How does nationalism influence current Canadian society?<br />

What role do you think <strong>the</strong> nation should play in <strong>the</strong> foundation of personal identity?<br />

In what ways does multiculturalism influence our national identity?<br />

In what ways is our national Canadian identity reflected through culture and <strong>the</strong> arts?<br />

*Read Europe at <strong>the</strong> Time of <strong>Aida</strong> to learn about how Verdi expressed nationalism<br />

through <strong>the</strong> arts!<br />

21<br />

Activity 3:<br />

Reader's Theatre<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

Drama Grades 4–9 Develop role-playing skills and specific storytelling skills<br />

Grades 10–12 Develop <strong>the</strong> ability to play a character from <strong>the</strong> character’s<br />

point of view<br />

ELA Grades 4–9 4.3 Present and Share<br />

Grades 10–12 5.2 Work within a group<br />

Student Objectives<br />

Students will demonstrate <strong>the</strong>ir understanding of <strong>the</strong> plot through performing<br />

a Reader’s Theatre of <strong>Aida</strong>. Allow students to read <strong>the</strong> <strong>Aida</strong> synopsis.<br />

As a class discuss <strong>the</strong> plot, characters, dilemmas, and resolution in <strong>the</strong> opera.<br />

Activity<br />

Divide <strong>the</strong> class into small groups and assign each group a part of <strong>the</strong> synopsis.<br />

Within each group designate characters and one narrator. Allow students time to<br />

practice <strong>the</strong>ir scene. Students will need to create <strong>the</strong>ir character's dialogue based on<br />

<strong>the</strong> assigned synopsis. After <strong>the</strong>y have prepared, <strong>the</strong> narrator for <strong>the</strong> group will read<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir section as <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r students act out <strong>the</strong> story. Groups will perform <strong>the</strong>ir part<br />

following <strong>the</strong> sequential order of <strong>Aida</strong>. If you have props or costumes incorporate <strong>the</strong>m<br />

too!

EDMONTON OPERA PRESENTS<br />

aida<br />

VERDI<br />

OCT 2012<br />

19 8.00 PM<br />

21 2.00 PM<br />

23 7.30 PM<br />

25 7.30 PM<br />

NORTHERN ALBERTA<br />

JUBILEE AUDITORIUM<br />

TICKETS from $50 || 780.429.1000 || www.edmontonopera.com<br />

22<br />

Activity 4:<br />

Poster Creation<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

Art Grades 5-6 Component 7: Composition, Component 10: Expression<br />

Grades 7-9 Drawing and Composition<br />

Grades 10-12 Drawing and Composition<br />

Activity<br />

When creating a poster for an opera <strong>the</strong>re are many things to consider. It is important<br />

to keep in mind <strong>the</strong> Director’s vision for <strong>the</strong> production and allow ample time for<br />

research through different resources such as online, literature, listening to <strong>the</strong> music,<br />

and watching o<strong>the</strong>r productions.<br />

When creating an image to represent an opera you must consider <strong>the</strong> time period,<br />

setting, <strong>the</strong>mes, characters, and plot. Our designer must also keep in mind our audience<br />

that we are trying to appeal to and what types of medium’s we will use to reach <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

After researching, it is important to sketch and brainstorm your ideas. It can be helpful<br />

to make a collage or mood board of different visuals and ideas that you would like<br />

to incorporate into <strong>the</strong> final image. O<strong>the</strong>r important factors include <strong>the</strong> hierarchy<br />

of information (what is <strong>the</strong> most important information and how will you show that<br />

importance – size of type, colour, location, etc), typography, colour (contrast, significance<br />

of colour), composition (placement, size and shape), and form among o<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

How would you illustrate <strong>Aida</strong>? Is your image a literal or symbolic portrayal?<br />

Using <strong>the</strong> synopsis, Message from <strong>the</strong> Director, and The Story Behind <strong>the</strong> Story<br />

create a poster using what you feel represents <strong>Aida</strong> <strong>the</strong> strongest.<br />

<strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> loves hearing from students! Send student posters<br />

to education@edmontonopera.com and <strong>the</strong>y may be posted on our website!

Activity 5:<br />

Facebook Character Development<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

ELA Grade 4–6 2.2 Respond to Texts<br />

Grade 7–9 1.2 Clarify and Extend<br />

Grade 10–12 2.1.2 Understand and Interpret Content<br />

Activity<br />

Students will explore and develop different characters in <strong>Aida</strong> by creating a Facebook<br />

profile. Discuss <strong>the</strong> characters as a class, talking about <strong>the</strong>ir importance and roles.<br />

Group students into small groups and assign one of <strong>the</strong> following characters:<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>, Radamès, Amneris, Amonasro, Ramfis, and Pharaoh.<br />

Encourage students to develop a profile for <strong>the</strong>ir assigned character including:<br />

interests, education, work, philosophy, arts, sports, likes, and o<strong>the</strong>r activities.<br />

Write three status updates that your character would write based on <strong>the</strong> storyline<br />

and events in <strong>Aida</strong>.<br />

Allow students to share <strong>the</strong>ir character insight amongst small groups followed<br />

by a classroom discussion.<br />

Questions for Discussion<br />

What groups is your character involved in? What types of friends do<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have?<br />

What types of goals does your character have? Do <strong>the</strong>y face any obstacles<br />

in achieving <strong>the</strong>se goals?<br />

Were you able to relate to your character? Can you understand why your character<br />

made <strong>the</strong> decisions that <strong>the</strong>y did?<br />

Verdi’s <strong>Aida</strong> first premiered in 1871; do you think <strong>the</strong> characters<br />

are still relevant today?<br />

23<br />

Activity 6<br />

<strong>Opera</strong> Notes<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

Music Grades 1-9 Listening<br />

Music Grades 10-12 Theoretical/Practical and Interpretation and Syn<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

ELA Grades 4-9 2.2 Respond to Texts, 3.4 Share and Review<br />

Grades 10-12 1.1 Discover possibilities, 2.3 Respond to a Variety<br />

of Print and Nonprint Texts<br />

Activity<br />

Students are encouraged to record <strong>the</strong>ir opinions during intermission and post-<br />

show using <strong>Opera</strong> Notes. This publication includes a synopsis, and cast information<br />

for students to take home!<br />

<strong>Edmonton</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> will have complementary printed copies available for students<br />

attending <strong>the</strong> dress rehearsal.<br />

See you at<br />

<strong>Aida</strong>!<br />

✐<br />

EDMONTON OPERA PRESENTS<br />

aida<br />

VERDI<br />

OCT 2012<br />

19 8.00 PM<br />

21 2.00 PM<br />

23 7.30 PM<br />

25 7.30 PM<br />

NORTHERN ALBERTA<br />

JUBILEE AUDITORIUM<br />

TICKETS from $50 || 780.429.1000 || www.edmontonopera.com