Title: Neuropsychological Features in Primary Hyperparathyroidism ...

Title: Neuropsychological Features in Primary Hyperparathyroidism ...

Title: Neuropsychological Features in Primary Hyperparathyroidism ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

J Cl<strong>in</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong> Metab. First published ahead of pr<strong>in</strong>t March 31, 2009 as doi:10.1210/jc.2008-2574<br />

<strong>Title</strong>: <strong>Neuropsychological</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Hyperparathyroidism</strong>: A Prospective Study<br />

Short title: <strong>Neuropsychological</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Hyperparathyroidism</strong><br />

Authors: Marcella D. Walker 1 , Donald J. McMahon 1 , William B. Inabnet 2 , Ronald M. Lazar 3 , Ijeoma<br />

Brown 1 , Susan Vardy 4 , Felicia Cosman 4 , and Shonni J. Silverberg 1<br />

Affiliations: 1 Department of Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, New York,<br />

New York; 2 Department of Surgery, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, New York,<br />

New York; 3 Department of Neurology, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, New York,<br />

New York; 4 Helen Hayes Hospital, Regional Bone Center, West Haverstraw, New York<br />

Correspond<strong>in</strong>g author:<br />

Marcella D. Walker, MD<br />

630 West 168 th Street<br />

PH8 West – 864<br />

New York, NY 10032<br />

212-305-6238 (telephone)<br />

212-305-6486 (fax)<br />

mad2037@columbia.edu<br />

Disclosure statement: The authors have noth<strong>in</strong>g to disclose.<br />

NIH statement: This is an un-copyedited author manuscript copyrighted by The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Society. This may<br />

not be duplicated or reproduced, other that for personal use or with<strong>in</strong> the rule of “Fair Use of Copyrighted<br />

Materials” (section 107, <strong>Title</strong> 17, U.S. Code) without permission of the copyright owner, The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Society. From the time of acceptance follow<strong>in</strong>g peer review, the full text of this manuscript is made freely<br />

available by The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Society at http://www.endojournals.org/. The f<strong>in</strong>al copy edited article can be<br />

found at http://www.endojournals.org/. The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Society disclaims any responsibility or liability for<br />

errors or omissions <strong>in</strong> this version of the manuscript or <strong>in</strong> any version derived from it by the National<br />

Institutes of Health or other parties. The citation of this article must <strong>in</strong>clude the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation:<br />

author(s), article title, journal title, year of publication, and DOI.<br />

A précis: Mild primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with cognitive changes affect<strong>in</strong>g verbal memory<br />

and non-verbal abstraction that improve after parathyroidectomy and are <strong>in</strong>dependent of anxiety and<br />

depressive symptoms<br />

Key words: primary hyperparathyroidism, cognition, psychiatric, depression, parathyroidectomy<br />

Word Count (text): 3629<br />

Word Count (abstract): 247<br />

Number of tables and figures: 6<br />

Address repr<strong>in</strong>t requests to Marcella D. Walker, MD<br />

Fund<strong>in</strong>g: This work was supported by NIH R01 DK32333, K24 DK74457, and UL1 RR024156<br />

1<br />

Copyright (C) 2009 by The Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Society

Abstract<br />

Context: Data regard<strong>in</strong>g the presence, extent and reversibility of psychological and cognitive features of<br />

primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) are conflict<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Objective: This study evaluated psychological and cognitive function symptoms <strong>in</strong> PHPT.<br />

Design: This is a case-control study <strong>in</strong> which symptoms and their improvement 6 months after surgical cure<br />

of PHPT were assessed.<br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>gs: University hospital metabolic bone disease unit and endocr<strong>in</strong>e surgery practice.<br />

Participants: 39 postmenopausal women with PHPT and 89 postmenopausal controls without PHPT.<br />

Intervention: Parathyroidectomy<br />

Outcome Measures: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Form Y (STAI-Y);<br />

North American Adult Read<strong>in</strong>g Test (NAART); Wechsler Memory Scale Logical Memory Test, Russell<br />

revision (LM); Buschke Selective Rem<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g Test (SRT); Rey Visual Design Learn<strong>in</strong>g Test (RVDLT);<br />

Booklet Category Test, Victoria revision (BCT); Rosen Target Detection Test (RTD); Wechsler Adult<br />

Intelligence Scale-Revised Digit Symbol Subtest (DSy); Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Digit Span<br />

Subtest (DSpan).<br />

Results: At basel<strong>in</strong>e, women with PHPT had significantly higher symptom scores for depression and anxiety<br />

than controls, and worse performance on tests of verbal memory (LM and SRT) and non-verbal abstraction<br />

(BCT). Depressive symptoms, non-verbal abstraction and some aspects of verbal memory (LM) improved<br />

after parathyroidectomy to the extent that scores <strong>in</strong> these doma<strong>in</strong>s were no longer different from controls.<br />

Basel<strong>in</strong>e differences and postoperative improvement <strong>in</strong> cognitive measures were <strong>in</strong>dependent of anxiety and<br />

depressive symptoms, and were not l<strong>in</strong>early associated with serum levels of calcium or parathyroid hormone.<br />

Conclusions: Mild PHPT is associated with cognitive features affect<strong>in</strong>g verbal memory and non-verbal<br />

abstraction that improve after parathyroidectomy.<br />

2

Introduction<br />

Classical PHPT was a symptomatic disease with commonly recognized neurologic, cognitive and<br />

psychiatric manifestations (1, 2). Many patients with PHPT are now asymptomatic or report only non-<br />

specific symptoms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g weakness, easy fatigability, depression, <strong>in</strong>tellectual wear<strong>in</strong>ess, loss of <strong>in</strong>itiative,<br />

anxiety, irritability, and sleep disturbance (3). While these symptoms are concern<strong>in</strong>g, they are difficult to<br />

quantify and there is debate about whether they are directly attributable to the underly<strong>in</strong>g disease. At the<br />

Third International Workshop on Asymptomatic <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Hyperparathyroidism</strong> (4), studies on the<br />

psychological and cognitive features of PHPT were reviewed and not considered to be an <strong>in</strong>dication for<br />

parathyroidectomy (5). The workshop recognized <strong>in</strong>consistencies <strong>in</strong> the abnormalities described, their<br />

association with the underly<strong>in</strong>g disease, and the extent to which these features were reversible after<br />

parathyroidectomy.<br />

A number of studies have attempted to del<strong>in</strong>eate the psychological and cognitive features of PHPT,<br />

and their resolution with surgical cure (6-24). Most have focused on psychological symptoms, such as<br />

depression, anxiety, or quality of life (QOL), rather than cognitive function such as logic, memory,<br />

abstraction, attention/concentration, and mental manipulation. Most have suggested that there are<br />

psychological features of the disease. A number of observational studies, some without control groups, report<br />

improved psychological symptoms or QOL with parathyroidectomy. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the 3 randomized controlled<br />

trials (RCTs) of parathyroidectomy <strong>in</strong> mild PHPT were <strong>in</strong>consistent; two found improved QOL after surgery<br />

(18, 25) while one did not (17).<br />

A smaller number of studies have exam<strong>in</strong>ed cognitive function <strong>in</strong> PHPT (6, 9, 12, 14, 15, 26-28).<br />

Explanations for the conflict<strong>in</strong>g results from these studies <strong>in</strong>clude: small sample sizes; <strong>in</strong>vestigation of only<br />

one or two aspects of cognition, mak<strong>in</strong>g generalization difficult; lack of control groups or validated measures<br />

<strong>in</strong> some studies and failure to take <strong>in</strong>to account demographic differences <strong>in</strong> others. Some studies monitored<br />

subjects shortly after parathyroidectomy, an experimental design which <strong>in</strong>troduces biases due to non-specific<br />

benefits of surgery. F<strong>in</strong>ally, no studies exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g cognitive function have assessed the <strong>in</strong>fluence of<br />

3

psychological symptoms upon cognition, which is critical s<strong>in</strong>ce depression and anxiety are known to affect<br />

cognitive function (29).<br />

Therefore, it rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear whether cognitive impairment is a feature of modern PHPT. The<br />

purpose of this study was (1) to exam<strong>in</strong>e whether cognitive function is affected <strong>in</strong> mild PHPT us<strong>in</strong>g a battery<br />

of tests that measure many different facets of cognition; (2) to evaluate psychological symptoms <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

adjust for the potentially confound<strong>in</strong>g effect of depression or anxiety on performance (3) to assess<br />

improvement <strong>in</strong> measures with surgical cure; and (4) to explore relationships between cognitive function and<br />

biochemical <strong>in</strong>dices of disease severity.<br />

Subjects and Methods<br />

This case-control study compared cognitive function and psychological symptoms between 2 groups<br />

of postmenopausal women: 1) those with PHPT who decided to undergo parathyroidectomy (either because<br />

they met 2002 surgical guidel<strong>in</strong>es (30) or preferred surgery over observation, despite not meet<strong>in</strong>g surgical<br />

<strong>in</strong>dications) and 2) normal controls. The prospective arm of the study assessed changes <strong>in</strong> these features<br />

after parathyroidectomy. All patients gave written, <strong>in</strong>formed consent. Patients were paid for participation <strong>in</strong><br />

the study and travel expenses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia<br />

University Medical Center and Helen Hayes Hospital.<br />

Subjects<br />

Subjects were female, age ≥ 45 years, menopausal for ≥ 1 years, English speak<strong>in</strong>g, and were<br />

recruited at Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons hospitals. PHPT patients were referred<br />

from the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Endocr<strong>in</strong>e Surgery Units at Columbia University Medical Center.<br />

Normal controls, recruited by newspaper advertisements, fliers and direct mail<strong>in</strong>g, were studied at Helen<br />

Hayes Hospital, West Haverstraw, NY. PHPT patients had hypercalcemia and an elevated or <strong>in</strong>appropriately<br />

normal parathyroid hormone (PTH) level. Exclusion criteria (<strong>in</strong> order to elim<strong>in</strong>ate the potential confound<strong>in</strong>g<br />

effects of sex, menopausal status, or significant co-morbidities on study outcomes) <strong>in</strong>cluded male sex,<br />

4

malignancy other than non-melanoma sk<strong>in</strong> cancer, alcoholism, significant liver or kidney disease, illnesses<br />

requir<strong>in</strong>g greater than 2 weeks of corticosteroids per year, traumatic bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jury or neurosurgery, seizure<br />

disorders, untreated mood disorders and use of lithium, hydrochlorothiazide, estrogen or other medications<br />

known to affect m<strong>in</strong>eral metabolism. Between September 2003 and December 2007, 119 women with PHPT<br />

were screened for enrollment, 46 were eligible and agreed to participate. The 73 women with PHPT who<br />

decl<strong>in</strong>ed participation were similar to those enrolled (mean±SEM): age 64.3±1.3 years, 98.6% white (97.2%<br />

non-Hispanic, 2.8 % Hispanic), 1.4% black. Three women <strong>in</strong> the PHPT group never underwent<br />

parathyroidectomy, two were not cured, and two were lost to follow-up, leav<strong>in</strong>g 39 evaluable cases. The<br />

control group <strong>in</strong>cluded 89 subjects without PHPT.<br />

The study was designed to have 80% power with 1% alpha-level to detect a between group<br />

difference of 0.62 standard deviations <strong>in</strong> the post- m<strong>in</strong>us pre- change <strong>in</strong> at least one of 4 test measures (Rosen<br />

Target Symbol, WAIS Logical Recall Immediate and Delayed and total score on Beck Depression<br />

Inventory). Cases and controls were enrolled <strong>in</strong> a 1:2 ratio to improve the precision of the estimate of change<br />

<strong>in</strong> cognitive function<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Study Design<br />

The PHPT group was evaluated pre-operatively with 9 standardized, validated cognitive and<br />

psychological tests. A serum sample was collected for measurement of biochemistries. Demographic factors<br />

and <strong>in</strong>formation on co-morbid conditions, and cl<strong>in</strong>ical symptoms were assessed by history. The PHPT group<br />

was re-evaluated us<strong>in</strong>g the same procedures six months post-operatively. This <strong>in</strong>terval was chosen to obviate<br />

biases that might be due to the non-specific benefits of surgery. The control group underwent test<strong>in</strong>g with the<br />

same test battery at an identical <strong>in</strong>terval.<br />

Biochemical Evaluation<br />

Serum calcium, album<strong>in</strong>, phosphate, blood urea nitrogen, creat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e, and alkal<strong>in</strong>e phosphatase<br />

activity were measured with colorimetric or spectrophotometric methods. Intact PTH was measured by<br />

5

immunochemilum<strong>in</strong>ometric assay (Scantibodies Laboratories, Inc.). Vitam<strong>in</strong> D metabolites were measured<br />

by radioimmunoassay (DiaSor<strong>in</strong>, Inc).<br />

Cognitive and Psychological Test<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Test<strong>in</strong>g, conducted by 3 <strong>in</strong>dividuals us<strong>in</strong>g identical procedures, lasted approximately 1.5 hours. Test<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrators were not bl<strong>in</strong>ded to disease state or time of test<strong>in</strong>g. Psychological tests refer to those<br />

measur<strong>in</strong>g depression (BDI) and anxiety (STAI) while the rema<strong>in</strong>der of the tests measured cognitive<br />

function.<br />

1. Estimated Intellectual Quotient (IQ): The NAART provides an estimate of <strong>in</strong>tellectual ability. Estimated<br />

full-scale IQ (FSIQ) scores are obta<strong>in</strong>ed: Estimated FSIQ=127.8 – (.78)(NAART errors) (31, 32). The mean<br />

normal value (±SD) is 100±15 (33).<br />

2. Depression: The BDI (2 nd ed.) is a 21-item depression severity scale for adults. Higher scores <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

more symptoms: 0-13 <strong>in</strong>dicates no or m<strong>in</strong>imal depression, 14-19 mild depression, 20-28 moderate<br />

depression, 29-63 severe depression (34).<br />

3. Anxiety: The STAI-Y (35) measures anxiety and consists of two 20-item scales, measur<strong>in</strong>g trait anxiety<br />

(anxiety proneness), and state anxiety (a current emotional condition). Mean raw values (± SD) for work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

adults, ages 50-69, are 32.2±8.7 for state anxiety and 31.8±7.8 for trait anxiety.<br />

4. Memory for Contextually Related Material: LM requires exam<strong>in</strong>ees to repeat two brief, orally-presented<br />

stories immediately and after a 30-m<strong>in</strong> delay. Results <strong>in</strong>dicate idea units recalled <strong>in</strong> the two stories (36).<br />

Immediate recall mean values (±SD) for <strong>in</strong>dividuals age 50-59 and 60-69 are 23.6±6.1 and 20.5±6.4<br />

respectively. Delayed recall mean values (±SD) for <strong>in</strong>dividuals age 50-59 and 60-69 are 20.1±6.5 and<br />

17.3±6.7 respectively (37).<br />

5. Word List Memory: The SRT (38, 39) assesses recall and learn<strong>in</strong>g for a word list. Results <strong>in</strong>dicate words<br />

correctly recalled over six trials (maximum=72) and after a 30-m<strong>in</strong> delay (maximum=12).<br />

6. Visual Memory: The RVDLT requires subjects to recall and draw visually-presented geometric designs.<br />

Results are scored as number of correctly reproduced designs dur<strong>in</strong>g three learn<strong>in</strong>g trials (40).<br />

6

7. Non-verbal Abstraction: This was assessed with the BCT, Victoria Revision (41), an 81-item version of<br />

the Halstead Category Test (HCT) (42), requir<strong>in</strong>g exam<strong>in</strong>ees to <strong>in</strong>fer the govern<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciple for sets of<br />

visual stimuli. Errors are summed and full HCT performance is predicted: 4.335 + [1.839 x (Victoria<br />

Revision errors)] (43), then converted to a T-score adjust<strong>in</strong>g for age, education and gender (42). T-scores are<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpreted as follows: ≥55 above average, 45-54 average, 40-44 below average, 35-39 mildly impaired, 30-<br />

34 mildly to moderately impaired, 25-29 moderately impaired, 20-24 moderately to severely impaired, and<br />

≤19 severely impaired.<br />

8. Visual Concentration/Attention: The RTD exam<strong>in</strong>es susta<strong>in</strong>ed visual concentration and attention.<br />

Exam<strong>in</strong>ees f<strong>in</strong>d a target among similar items. Results <strong>in</strong>dicate time to completion and errors. The mean<br />

normal value (±SD) for the symbol version of the test and errors are 35.7±8.4 and 3.8±2.8 respectively. The<br />

DSy (33) measures response speed and visual attention. Exam<strong>in</strong>ees fill <strong>in</strong> the blank squares with a nonsense<br />

symbol correspond<strong>in</strong>g to a digit. Results are scored as symbols transcribed <strong>in</strong> 90 seconds. Raw scores are<br />

converted to scaled scores, which adjusts for age differences. The mean scaled score (±SD) is 10±3 (33).<br />

9. Auditory Attention and Mental Manipulation: The DSpan tests immediate span of auditory attention and<br />

mental manipulation (mean scaled score (±SD) is 10±3) (33).<br />

Statistics<br />

Differences between PHPT and control test performance at basel<strong>in</strong>e and after 6-months were<br />

evaluated for each outcome with l<strong>in</strong>ear mixed models for repeated measures with fixed effects for group,<br />

time and their <strong>in</strong>teraction, random effect of subjects and an unstructured covariance structure. Model<br />

estimated means + SEM adjusted for covariates are reported. The method of simultaneous confidence limits<br />

was used to assess between-groups differences at basel<strong>in</strong>e or 6-months when the effects of group or the<br />

group-by-time <strong>in</strong>teraction atta<strong>in</strong>ed statistical significance, and aga<strong>in</strong> for with<strong>in</strong>-groups differences between<br />

times when the fixed effects of time or group-by-time <strong>in</strong>teraction achieved statistical significance. Test<br />

scores were adjusted for age, education and sex as suggested by the test manual when methods of adjustment<br />

were available. S<strong>in</strong>ce not all tests had methods of correction, all scores were additionally adjusted<br />

statistically for age, education and estimated IQ. Scores were not adjusted for years s<strong>in</strong>ce menopause due to<br />

7

its co-l<strong>in</strong>earity with age. Education level was coded as number of years of school<strong>in</strong>g completed. Cognitive<br />

measures were also evaluated with adjustment for levels of anxiety and depression to m<strong>in</strong>imize the <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

of affective factors on cognition. L<strong>in</strong>ear associations between biochemical measures and cognitive and<br />

psychological test scores were assessed with Pearson correlation coefficients. For all analyses, a two-tailed<br />

p≤0.05 was considered to <strong>in</strong>dicate statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed us<strong>in</strong>g SAS,<br />

Version 9.1.3 (Cary, NC).<br />

Results<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical and Biochemical Results<br />

Cases had biochemical evidence of PHPT (serum calcium: 10.6±0.1 mg/dl; PTH: 77±4 pg/ml; Table<br />

1). At basel<strong>in</strong>e, PHPT patients were slightly older (61.3±1.0 vs. 55.6±0.4 years; p

PHPT, mean performance levels on these tests were not <strong>in</strong> a range suggestive of cl<strong>in</strong>ical depression or<br />

anxiety. Depressive symptoms improved - the pattern of change <strong>in</strong> depressive symptoms over time differed<br />

between the groups (group by time <strong>in</strong>teraction; p=0.024) such that there was no difference between the<br />

control and postoperative groups (PHPT 5.2±1.0 versus control 3.7±0.8, p=0.28) after parathyroidectomy.<br />

Trait anxiety but not state anxiety decreased after parathyroidectomy <strong>in</strong> the PHPT group compared to<br />

basel<strong>in</strong>e. However, there were no differences <strong>in</strong> change over time between the groups for either trait or state<br />

anxiety (p=0.152 and p=0.184, respectively).<br />

Cognitive Function<br />

Memory: Those with PHPT had worse scores for both immediate and delayed recall of contextually related<br />

material (immediate: 17.2±0.9 versus 20.6±0.8, p=0.01; delayed: 12±0.9 versus 16.0±0.7, p=0.002; Figure<br />

2). Both tests improved to levels that were no longer different from control subjects after parathyroidectomy<br />

(immediate: 20.0±0.8 versus 20.0±0.7, p=0.97; delayed: 14.5±0.9 versus 15.7±0.8, p=0.36), and the change<br />

over time differed between normal and PHPT subjects (p=0.003 immediate and p=0.009 delayed recall).<br />

Immediate, but not delayed, word list recall (SRT) was also worse at basel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the PHPT group (immediate:<br />

49.2±1.3 versus 53±1.1, p=0.04; delayed: 6.8±0.4 versus 7.9±0.4, p=0.064). Neither immediate nor delayed<br />

recall changed with surgery (Figure 3). No differences were found between PHPT and controls <strong>in</strong> visual<br />

memory (Table 3). Both groups improved to similar extents over time, consistent with a learn<strong>in</strong>g effect.<br />

Other cognitive functions: Non-verbal abstraction was worse <strong>in</strong> the PHPT group (39.9±1.9 versus 45.6±1.6,<br />

p=0.041, Figure 4). While scores <strong>in</strong> both PHPT and control subjects improved over time, those with PHPT<br />

improved to a greater extent, so that they were <strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable from normal subjects (49.5±2.3 versus<br />

50.5±1.9, p=0.74; group by time <strong>in</strong>teraction: p=0.036). Visual concentration and attention as measured by the<br />

RTD or Digit Symbol test was similar <strong>in</strong> the PHPT and control groups (Table 3). While target detection did<br />

not change over time, the PHPT group improved compared to basel<strong>in</strong>e on one test of visual concentration<br />

and attention (Digit Symbol test), while the control group did not (between groups change over time,<br />

9

p=0.014). There was no difference on performance on the Digit Span test of auditory attention and mental<br />

manipulation and neither group improved compared to basel<strong>in</strong>e (Table 3).<br />

Association of psychological and cognitive test results with disease severity<br />

No l<strong>in</strong>ear associations were observed between any psychological or cognitive variable that was<br />

abnormal at basel<strong>in</strong>e and serum calcium, PTH, or vitam<strong>in</strong> D metabolite concentration, nor was a relationship<br />

observed between changes <strong>in</strong> psychological or cognitive variables and change <strong>in</strong> biochemical measures.<br />

Discussion<br />

The nature and extent of psychological and cognitive <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> PHPT rema<strong>in</strong>s an area of great<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest. While earlier studies have arbitrarily selected one or two aspects of cognitive function, this study<br />

used a wide array of tests because the facets of cognition that could be affected by PHPT were unclear a<br />

priori. We sought to document the presence of any abnormalities, to determ<strong>in</strong>e their reversibility, and their<br />

relationship to ambient serum calcium, PTH, and other biochemical <strong>in</strong>dices of the disease. A control<br />

population allowed for assessment of learn<strong>in</strong>g effects on repeated test<strong>in</strong>g. The results of statistical analyses<br />

demonstrate that PHPT <strong>in</strong> post-menopausal women is associated with alterations <strong>in</strong> cognition that are<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent of depression and anxiety. Those with PHPT performed less well than control subjects on some<br />

tests of cognitive function, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g tests of verbal memory and non-verbal abstraction. Non-verbal<br />

abstraction and some aspects of verbal memory improved after parathyroidectomy. Visual memory and<br />

concentration and auditory attention and mental manipulation were not impaired. F<strong>in</strong>ally, while patients with<br />

PHPT were not cl<strong>in</strong>ically depressed or anxious, they had more symptoms of depression and anxiety than<br />

control subjects. Depressive symptoms decreased after parathyroidectomy, while anxiety did not.<br />

Many case-control studies (7, 11, 16, 22, 23) and a recent RCT (17) support the presence of<br />

psychological symptoms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g depression, anxiety, fearfulness, <strong>in</strong>feriority, lassitude, lack of <strong>in</strong>itiative,<br />

fatigability, and apathy (11, 16, 23), or decreased QOL (7, 17, 22) <strong>in</strong> PHPT. While observational studies<br />

have tended to show improvement of these symptoms with parathyroidectomy (7, 11, 13, 16, 19, 21, 22, 24),<br />

10

RCT results have been <strong>in</strong>consistent (17, 25, 44). Rao et al. (44) found (us<strong>in</strong>g SF-36 and SCL-90R) a<br />

worsen<strong>in</strong>g of social function<strong>in</strong>g and emotional problem doma<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> patients followed without <strong>in</strong>tervention for<br />

2 years, although there was little improvement <strong>in</strong> the operative group. Those who had surgery, however, had<br />

a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> anxiety and phobic symptoms. Bollerslev et al. found significantly lower basel<strong>in</strong>e QOL (SF-36)<br />

and more psychological symptoms, but did not demonstrate postoperative improvement (17). Ambrog<strong>in</strong>i et<br />

al. reported a modest benefit of surgery <strong>in</strong> four QOL doma<strong>in</strong>s (SF-36), <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g bodily pa<strong>in</strong>, general health,<br />

vitality, and mental health, but found no difference <strong>in</strong> SCL-90R measures (25). Possible explanations for the<br />

conflict<strong>in</strong>g results of these studies could <strong>in</strong>clude differences <strong>in</strong> the size and composition of the populations<br />

sampled, type of analyses performed or differential attrition <strong>in</strong> the studies. Our study specifically measured<br />

depression and anxiety, because they are known confounders of neuropsychological test<strong>in</strong>g. Together with<br />

the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the current report, the available results support the presence of some depressive and anxiety<br />

symptoms <strong>in</strong> PHPT.<br />

Few other studies have exam<strong>in</strong>ed cognitive function <strong>in</strong> PHPT. The clear learn<strong>in</strong>g effect over test<strong>in</strong>g<br />

trials, as was evident <strong>in</strong> our <strong>in</strong>vestigation, limits the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of studies without control groups (6, 14,<br />

26, 45). Comparison of this report to the few exist<strong>in</strong>g controlled studies is difficult because each employed a<br />

different battery of tests, assessed <strong>in</strong>dividuals at different <strong>in</strong>tervals from surgery and <strong>in</strong>cluded populations<br />

with vary<strong>in</strong>g calcium levels. Furthermore, no prior studies have adjusted for the presence of anxiety or<br />

depression symptoms. Numann et al. used a large battery of tests and found post-parathyroidectomy<br />

improvement <strong>in</strong> verbal memory as we did. Their positive f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs despite a very small sample size (10<br />

patients undergo<strong>in</strong>g parathyroidectomy and 10 normocalcemic orthopedic controls) may be due to the more<br />

severe disease <strong>in</strong> their patients (12). Roman et al. compared 2 tests of cognitive function <strong>in</strong> patients with<br />

PHPT and those with benign goiter preoperatively 2 and 4 weeks post-operatively (15). In contrast to our<br />

study, they did not f<strong>in</strong>d impaired memory for word lists compared to controls, but did f<strong>in</strong>d changes <strong>in</strong> spatial<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g and memory, which our study did not assess. Two other studies found no cognitive impairment <strong>in</strong><br />

PHPT or postoperative improvement, but may have been underpowered to do so (n=14 and n=20) (27, 28).<br />

11

We found no l<strong>in</strong>ear association between serum calcium or PTH and cognitive abnormalities. This<br />

may be because the study had limited power to evaluate this relationship or the range of serum calcium and<br />

PTH levels was too narrow to be able to discern the association. Studies <strong>in</strong> which the mean serum calcium<br />

values were much higher reported a relationship between preoperative neuropsychological symptoms and<br />

extent of hypercalcemia (19). Several studies from our group and others support the presence of <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

vascular stiffness and endothelial dysfunction <strong>in</strong> PHPT (46-49). If present <strong>in</strong> the carotid or cerebral<br />

vasculature, vascular stiffness could represent a pathophysiological pathway lead<strong>in</strong>g to cognitive impairment.<br />

The study has several limitations. First, the PHPT and control groups differed with regard to two<br />

important parameters: estimated IQ and education level. The direction of the differences (PHPT subjects<br />

were better educated and with a higher estimated IQ), however, should have biased aga<strong>in</strong>st our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

worse cognitive function <strong>in</strong> the PHPT group. Although these differences were taken <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>in</strong> the<br />

statistical analysis, adjustment may not fully account for these disparities. It is therefore possible, that if cases<br />

could have been ideally matched, the results may have differed. Although specific socioeconomic data were<br />

not available, the communities from which the samples were obta<strong>in</strong>ed are similar <strong>in</strong> this regard. We also<br />

suspect an association between socioeconomic level and education, for which we adjusted.<br />

There were also limitations <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> the study design. An RCT of surgery versus no surgery is a<br />

superior design compared to a case-control study, but is extremely difficult to carry-out. Additionally, test<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrators were not bl<strong>in</strong>ded to disease state and time of test<strong>in</strong>g, which could have <strong>in</strong>fluenced results.<br />

Because we did not have a surgical control group, it is also possible that the pre-operative <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong><br />

symptoms of anxiety and depression could be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by anticipation of surgery. Improvement <strong>in</strong><br />

psychiatric symptoms may have been due to the knowledge of be<strong>in</strong>g free of disease or a non-specific effect<br />

of surgery rather than the correction of PHPT itself. However, if preoperative anxiety f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs were related<br />

to impend<strong>in</strong>g surgery, an improvement would have been expected. F<strong>in</strong>ally, we studied a convenience sample<br />

of PHPT patients <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g patients who did and did not meet 2002 criteria for surgery. The size of the<br />

cohort precludes a sub-group analysis (of those meet<strong>in</strong>g versus those not meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dications for surgery) to<br />

12

address the issue of differ<strong>in</strong>g responses <strong>in</strong> these groups. However, it allowed us to achieve our ma<strong>in</strong> goal: to<br />

document the existence of cognitive symptoms among patients with mild PHPT.<br />

The cl<strong>in</strong>ical significance of the cognitive improvement after surgery is unclear, s<strong>in</strong>ce the magnitude<br />

of changes was with<strong>in</strong> one standard deviation of the group mean. It is notable, however, that the mean value<br />

for nonverbal abstraction, logic and problem solv<strong>in</strong>g was with<strong>in</strong> 1 po<strong>in</strong>t of the mildly impaired range, a<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that was unexpected given participants’ high level of education. In addition, we do not know if these<br />

results apply to premenopausal women and men with PHPT.<br />

In spite of these limitations, the study has several notable strengths. We characterized cognitive<br />

function <strong>in</strong> a moderate sized group of patients with mild PHPT. Control data are available and a large battery<br />

of validated tests, which evaluated many aspects of cognition, was used. Patients and controls were studied<br />

at two identical time po<strong>in</strong>ts, obviat<strong>in</strong>g confound<strong>in</strong>g by learn<strong>in</strong>g effects known to exist <strong>in</strong> cognitive test<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Additionally, we studied patients well after the immediate post-operative period <strong>in</strong> order to prevent biases<br />

due to the non-specific benefits of surgery. F<strong>in</strong>ally, we controlled for variables known to affect cognitive<br />

performance, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g age, education and estimated IQ, and the presence of anxiety and depressive<br />

symptoms.<br />

We conclude that mild PHPT <strong>in</strong> postmenopausal women is associated with weaker performance <strong>in</strong><br />

the cognitive doma<strong>in</strong>s of verbal memory and non-verbal abstraction. This is <strong>in</strong>dependent of anxiety and<br />

depressive symptoms, which are also more common <strong>in</strong> PHPT than <strong>in</strong> a control population.<br />

Parathyroidectomy leads to improvement <strong>in</strong> some of the psychiatric and cognitive deficits. While these<br />

results cannot be extrapolated to predict cl<strong>in</strong>ical expectations <strong>in</strong> any given patient, they may provide an<br />

explanation for the improved sense of well-be<strong>in</strong>g reported by many, but not all, patients after successful<br />

parathyroidectomy. Furthermore, these results may be useful <strong>in</strong> further research <strong>in</strong>to specific<br />

neuroanatomical regions that may be specifically affected by the hyperparathyroid process.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

13

We are grateful to Dr. John Bilezikian for his counsel and support throughout this project.<br />

References<br />

1. Cope O 1966 The story of hyperparathyroidism at the Massachusetts General Hospital. N<br />

Engl J Med 21:1174-1182<br />

2. Albright F, Aub J, Bauer W 1934 <strong>Hyperparathyroidism</strong>: a common and polymorphic<br />

condition as illustrated by seventeen proved cases from one cl<strong>in</strong>ic. JAMA 102:1276-1287<br />

3. Silverberg SJ 2002 Non-classical target organs <strong>in</strong> primary hyperparathyroidism. J Bone<br />

M<strong>in</strong>er Res 17 Suppl 2:N117-25<br />

4. Silverberg SJ, Lewiecki EM, Mosekilde L, Peacock M, Rub<strong>in</strong> MR 2009 Presentation of<br />

asympotomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of the Third International<br />

Workshop. Journal of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology (<strong>in</strong> press)<br />

5. Bilezikian JP, Khan A, Arnold A, Brandi ML, Brown E, Bouillon R, Camacho P, Clark<br />

O, D'Amour P, Eastell R, Goltzman D, Hanley DA, Lewiecki EM, Marx S, Mosekilde<br />

L, Pasieka JL, Peacock M, Rao D, Reid IR, Rub<strong>in</strong> M, Shoback D, Silverberg S,<br />

Sturgeon C, Udelsman R, Young JRM, Potts JT 2009 Guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the Management of<br />

Asympotmatic <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Hyperparathyroidism</strong>: Summary Statement from the Third<br />

International Workshop. Journal of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology (<strong>in</strong> press)<br />

6. Brown GG, Preisman RC, Kleerekoper M 1987 Neurobehavioral symptoms <strong>in</strong> mild<br />

primary hyperparathyroidism: related to hypercalcemia but not improved by<br />

parathyroidectomy. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 35:211-5<br />

7. Burney RE, Jones KR, Christy B, Thompson NW 1999 Health status improvement after<br />

surgical correction of primary hyperparathyroidism <strong>in</strong> patients with high and low<br />

preoperative calcium levels. Surgery 125:608-14<br />

8. Caillard C, Sebag F, Mathonnet M, Gibel<strong>in</strong> H, Brunaud L, Loudot C, Kraimps JL,<br />

Hamy A, Bresler L, Charbonnel B, Leborgne J, Henry JF, Nguyen JM, Mirallie E 2007<br />

Prospective evaluation of quality of life (SF-36v2) and nonspecific symptoms before and<br />

after cure of primary hyperparathyroidism (1-year follow-up). Surgery 141:153-9;<br />

discussion 159-60<br />

9. Dotzenrath CM, Kaetsch AK, Pf<strong>in</strong>gsten H, Cupisti K, Weyerbrock N, Vossough A,<br />

Verde PE, Ohmann C 2006 Neuropsychiatric and Cognitive Changes after Surgery for<br />

<strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Hyperparathyroidism</strong>. World J Surg 5:680-685<br />

10. Eigelberger MS, Cheah WK, Ituarte PH, Streja L, Duh QY, Clark OH 2004 The NIH<br />

criteria for parathyroidectomy <strong>in</strong> asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: are they too<br />

limited? Ann Surg 239:528-35<br />

11. Joborn C, Hetta J, L<strong>in</strong>d L, Rastad J, Akerstrom G, Ljunghall S 1989 Self-rated<br />

psychiatric symptoms <strong>in</strong> patients operated on because of primary hyperparathyroidism and<br />

<strong>in</strong> patients with long-stand<strong>in</strong>g mild hypercalcemia. Surgery 105:72-8<br />

12. Numann PJ, Torppa AJ, Blumetti AE 1984 Neuropsychologic deficits associated with<br />

primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 96:1119-23<br />

13. Pasieka JL, Parsons LL 1998 Prospective surgical outcome study of relief of symptoms<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g surgery <strong>in</strong> patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg 22:513-8;<br />

discussion 518-9<br />

14

14. Prager G, Kalaschek A, Kaczirek K, Passler C, Scheuba C, Sonneck G, Niederle B<br />

2002 Parathyroidectomy improves concentration and retentiveness <strong>in</strong> patients with primary<br />

hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 132:930-5; discussion 935-6<br />

15. Roman SA, Sosa JA, Mayes L, Desmond E, Boudourakis L, L<strong>in</strong> R, Snyder PJ, Holt E,<br />

Udelsman R 2005 Parathyroidectomy improves neurocognitive deficits <strong>in</strong> patients with<br />

primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 138:1121-8; discussion 1128-9<br />

16. Solomon BL, Schaaf M, Smallridge RC 1994 Psychologic symptoms before and after<br />

parathyroid surgery. Am J Med 96:101-6<br />

17. Bollerslev J, Jansson S, Mollerup CL, Nordenstrom J, Lundgren E, Torr<strong>in</strong>g O,<br />

Varhaug JE, Baranowski M, Aanderud S, Franco C, Freyschuss B, Isaksen GA,<br />

Ueland T, Rosen T 2007 Medical observation, compared with parathyroidectomy, for<br />

asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective, randomized trial. J Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Endocr<strong>in</strong>ol Metab 92:1687-92<br />

18. Talpos GB, Bone HG, 3rd, Kleerekoper M, Phillips ER, Alam M, Honasoge M, Div<strong>in</strong>e<br />

GW, Rao DS 2000 Randomized trial of parathyroidectomy <strong>in</strong> mild asymptomatic primary<br />

hyperparathyroidism: patient description and effects on the SF-36 health survey. Surgery<br />

128:1013-20;discussion 1020-1<br />

19. Weber T, Keller M, Hense I, Pietsch A, H<strong>in</strong>z U, Schill<strong>in</strong>g T, Nawroth P, Klar E,<br />

Buchler MW 2007 Effect of parathyroidectomy on quality of life and neuropsychological<br />

symptoms <strong>in</strong> primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg 31:1202-9<br />

20. Burney RE, Jones KR, Peterson M, Christy B, Thompson NW 1998 Surgical correction<br />

of primary hyperparathyroidism improves quality of life. Surgery 124:987-91; discussion<br />

991-2<br />

21. Quiros RM, Alef MJ, Wilhelm SM, Djuric<strong>in</strong> G, Loviscek K, Pr<strong>in</strong>z RA 2003 Healthrelated<br />

quality of life <strong>in</strong> hyperparathyroidism measurably improves after parathyroidectomy.<br />

Surgery 134:675-81; discussion 681-3<br />

22. Sheldon DG, Lee FT, Neil NJ, Ryan JA, Jr. 2002 Surgical treatment of<br />

hyperparathyroidism improves health-related quality of life. Arch Surg 137:1022-6;<br />

discussion 1026-8<br />

23. Lundgren E, Ljunghall S, Akerstrom G, Hetta J, Mallm<strong>in</strong> H, Rastad J 1998 Casecontrol<br />

study on symptoms and signs of "asymptomatic" primary hyperparathyroidism.<br />

Surgery 124:980-5; discussion 985-6<br />

24. Okamoto T, Kamo T, Obara T 2002 Outcome study of psychological distress and<br />

nonspecific symptoms <strong>in</strong> patients with mild primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Surg<br />

137:779-83; discussion 784<br />

25. Ambrog<strong>in</strong>i E, Cetani F, Cianferotti L, Vignali E, Banti C, Viccica G, Oppo A, Miccoli<br />

P, Berti P, Bilezikian JP, P<strong>in</strong>chera A, Marcocci C 2007 Surgery or surveillance for mild<br />

asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective, randomized cl<strong>in</strong>ical trial. J Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Endocr<strong>in</strong>ol Metab 92:3114-21<br />

26. Mittendorf EA, Wefel JS, Meyers CA, Doherty D, Shapiro SE, Lee JE, Evans DB,<br />

Perrier ND 2007 Improvement of sleep disturbance and neurocognitive function after<br />

parathyroidectomy <strong>in</strong> patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Endocr Pract 13:338-44<br />

27. Goyal A, Chumber S, Tandon N, Lal R, Srivastava A, Gupta S 2001 Neuropsychiatric<br />

manifestations <strong>in</strong> patients of primary hyperparathyroidism and outcome follow<strong>in</strong>g surgery.<br />

Indian J Med Sci 55:677-86<br />

28. Chiang CY, Andrewes DG, Anderson D, Devere M, Schweitzer I, Zajac JD 2005 A<br />

controlled, prospective study of neuropsychological outcomes post parathyroidectomy <strong>in</strong><br />

primary hyperparathyroid patients. Cl<strong>in</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ol (Oxf) 62:99-104<br />

15

29. Coker LH, Rorie K, Cantley L, Kirkland K, Stump D, Burbank N, Tembreull T,<br />

Williamson J, Perrier N 2005 <strong>Primary</strong> hyperparathyroidism, cognition, and health-related<br />

quality of life. Ann Surg 242:642-50<br />

30. Bilezikian JP, Potts JT, Jr. 2002 Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: new issues<br />

and new questions--bridg<strong>in</strong>g the past with the future. J Bone M<strong>in</strong>er Res 17 Suppl 2:N57-67<br />

31. Lezak MD 1995 <strong>Neuropsychological</strong> Assessment. Oxford University Press, New York<br />

32. Spreen O, Strauss E 1991 A compendium of neuropsychological tests: adm<strong>in</strong>istration,<br />

norms, and commentary. Oxford University press, New York<br />

33. Wechsler D 1981 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised Manual. Harcourt Brace<br />

Jovanovich, Inc, San Antonio, Texas<br />

34. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK 1996 Beck Depression Inventory Manual. Harcourt Brace<br />

and Company, San Antonio<br />

35. Spielberger CD 1977 State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Manual, Test, Scor<strong>in</strong>g Key. M<strong>in</strong>d<br />

Garden Inc., Redwood City, CA<br />

36. Wechsler D 1945 A standardized memory scale for cl<strong>in</strong>ical use. Journal of Psychology<br />

19:87-95<br />

37. Abikoff H, Alvir J, Hong G, Sukoff R, Orazio J, Solomon S, Saravay S 1987 Logical<br />

memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale: age and education norms and alternateform<br />

reliability of two scor<strong>in</strong>g systems. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Exp Neuropsychol 9:435-48<br />

38. Buschke H 1973 Selective rem<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g for analysis of memory and learn<strong>in</strong>g. Journal of<br />

Verbal Learn<strong>in</strong>g and Verbal Behavior 12:543-550<br />

39. Buschke H, Fuld PA 1974 Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g storage, retention, and retrieval <strong>in</strong> disordered<br />

memory and learn<strong>in</strong>g. Neurology 24:1019-25<br />

40. Rey A 1964 L'examen cl<strong>in</strong>ique en Psychologie. Presse Universitaire de France, Paris<br />

41. Labreche TM 1983 The Victoria revision of the booklet category test. University of<br />

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada<br />

42. Defilippis N, McCambell E 1991 The Booklet Category Test. Psychological Assessment<br />

Resources, Inc, Odessa, FL<br />

43. Kozel JJ, Meyers JE 1998 A cross-validation study of the Victoria Revision of the<br />

Category Test. Arch Cl<strong>in</strong> Neuropsychol 13:327-32<br />

44. Rao DS, Phillips ER, Div<strong>in</strong>e GW, Talpos GB 2004 Randomized controlled cl<strong>in</strong>ical trial of<br />

surgery versus no surgery <strong>in</strong> patients with mild asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism.<br />

J Cl<strong>in</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ol Metab 89:5415-22<br />

45. McAllion SJ, Paterson CR 1989 Psychiatric morbidity <strong>in</strong> primary hyperparathyroidism.<br />

Postgrad Med J 65:628-31<br />

46. Rub<strong>in</strong> MR, Maurer MS, McMahon DJ, Bilezikian JP, Silverberg SJ 2005 Arterial<br />

stiffness <strong>in</strong> mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Endocr<strong>in</strong>ol Metab 90:3326-30<br />

47. Smith JC, Page MD, John R, Wheeler MH, Cockcroft JR, Scanlon MF, Davies JS 2000<br />

Augmentation of central arterial pressure <strong>in</strong> mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Endocr<strong>in</strong>ol Metab 85:3515-9<br />

48. Nilsson IL, Aberg J, Rastad J, L<strong>in</strong>d L 1999 Endothelial vasodilatory dysfunction <strong>in</strong><br />

primary hyperparathyroidism is reversed after parathyroidectomy. Surgery 126:1049-55<br />

49. Kosch M, Hausberg M, Vormbrock K, Kisters K, Gabriels G, Rahn KH, Barenbrock<br />

M 2000 Impaired flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery <strong>in</strong> patients with primary<br />

hyperparathyroidism improves after parathyroidectomy. Cardiovasc Res 47:813-8<br />

16

Figure legends<br />

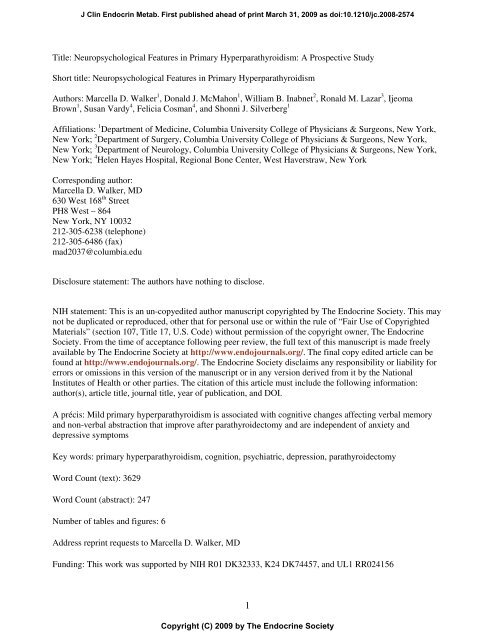

Figure 1. A) Depression measured by BDI; B) State and C) Trait anxiety as measured by STAI-Y.<br />

Higher scores <strong>in</strong>dicate more symptoms. Scores are adjusted for age, IQ and education. *,<br />

p

Table 1. Biochemical variables pre- and post-operatively PHPT group<br />

Normal<br />

range<br />

Pre-<br />

Parathyroidectomy<br />

18<br />

Mean ± SEM<br />

PHPT<br />

Post-<br />

Parathyroidectomy<br />

Mean ± SEM<br />

Pre- vs.<br />

Post-op<br />

P-value<br />

Serum calcium (mg/dl) 8.5-10.2 10.6 ± 0.1 9.5 ± 0.1

Table 2. Cognitive Test<strong>in</strong>g Adjusted for Age, IQ, Education, Anxiety and Depression<br />

Cognitive Test<br />

Time 1<br />

(Pre-op)<br />

Mean ± SEM<br />

PHPT group Control group<br />

Time 2<br />

(Post-op)<br />

Mean ± SEM<br />

19<br />

Time 1<br />

Mean ± SEM<br />

Time 2<br />

Mean ± SEM<br />

PHPT vs.<br />

Controls<br />

(Time 1)<br />

p-value<br />

PHPT vs.<br />

Controls<br />

(Time 2)<br />

p-value<br />

Visual Memory<br />

RVDLT Total Trials 1-3 16.6 ± 1.0 19.3 ± 0.9* 17.3 ± 0.86 19.1 ± 0.8* 0.639 0.886<br />

Response Speed/Visual Concentrations<br />

Rosen Detection Test - Symbol Time 43.0 ± 2.3 40.5 ± 1.9 40.6 ± 1.9 42.6 ± 1.7 0.440 0.465<br />

Rosen Detection Test - Symbol Error 2.5 ± 0.5 3.2 ± 0.5 3.1 ± 0.4 2.9 ± 0.5 0.423 0.709<br />

WAIS-R Digit Symbol Standard Score 13.0 ± 0.4 13.5 ± 0.4* 13.3 ±0.3 13.1 ± 0.3 0.662 0.406<br />

Auditory Attention/Mental Manipulation<br />

Digit Span Total Standard Score 12.3 ± 0.4 12.0 ± 0.4 11.4 ± 0.3 11.7 ± 0.4 0.089 0.622<br />

*<strong>in</strong>dicates p

Figure 1<br />

A.<br />

B.<br />

C.<br />

Beck Depression Inventory<br />

STAI-Y<br />

STAI-Y<br />

12.00<br />

10.00<br />

8.00<br />

6.00<br />

4.00<br />

2.00<br />

38.00<br />

36.00<br />

34.00<br />

32.00<br />

30.00<br />

28.00<br />

26.00<br />

24.00<br />

22.00<br />

20.00<br />

40.00<br />

38.00<br />

36.00<br />

34.00<br />

32.00<br />

30.00<br />

28.00<br />

26.00<br />

24.00<br />

22.00<br />

20.00<br />

*<br />

†<br />

†<br />

Depression<br />

1 2<br />

Time<br />

State Anxiety<br />

1 2<br />

Tim e<br />

Tra it Anx ie ty<br />

1 2<br />

Tim e<br />

+<br />

+<br />

PHPT<br />

Control<br />

PHPT<br />

Control<br />

PHPT<br />

Control

Figure 2<br />

A.<br />

Wechsler Logical<br />

Memory<br />

B.<br />

Wechsler Logical<br />

Memory<br />

22.00<br />

20.00<br />

18.00<br />

16.00<br />

14.00<br />

12.00<br />

10.00<br />

18.00<br />

17.00<br />

16.00<br />

15.00<br />

14.00<br />

13.00<br />

12.00<br />

11.00<br />

10.00<br />

9.00<br />

8.00<br />

Verbal Memory<br />

Contextually Related Material (Immediate)<br />

Verbal Memory<br />

Contextually Related Material (Delayed)<br />

*<br />

*<br />

1 2<br />

Time<br />

1 2<br />

Time<br />

+<br />

+<br />

PHPT<br />

Control<br />

PHPT<br />

Control

Figure 3<br />

A.<br />

Bushke SRT Total Recall<br />

B.<br />

Bushke SRT Total Recall<br />

55.00<br />

54.00<br />

53.00<br />

52.00<br />

51.00<br />

50.00<br />

49.00<br />

48.00<br />

47.00<br />

46.00<br />

9.00<br />

8.00<br />

7.00<br />

6.00<br />

5.00<br />

4.00<br />

Verbal Memory - Immediate Word List<br />

†<br />

1 2<br />

Time<br />

Verbal Memory - Delayed Word List<br />

1 2<br />

Time<br />

*<br />

PHPT<br />

Control<br />

PHPT<br />

Control

Figure 4<br />

Booklet Category Test<br />

T-score<br />

55.00<br />

50.00<br />

45.00<br />

40.00<br />

35.00<br />

30.00<br />

†<br />

Non-verbal Abstraction<br />

1 2<br />

Time<br />

+<br />

+<br />

PHPT<br />

Control