Histories of Green Square - City of Sydney

Histories of Green Square - City of Sydney

Histories of Green Square - City of Sydney

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Histories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Square</strong><br />

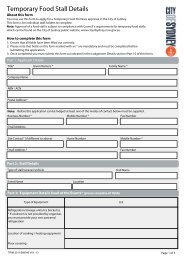

Fig. 6.1 Photographer Sam Hood captured this portrait <strong>of</strong> local Alexandria people who had gathered to watch a fire <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Metters factory in 1934. (Source: Sam Hood, ‘Crowds watch over the back fence’, Hood Collection, courtesy <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mitchell Library, State Library <strong>of</strong> NSW.)<br />

The earlier industries were rural-based and demonstrate the<br />

relationship between the growing town and its rural hinterland.<br />

The Lachlan and Waterloo Mills represent some <strong>of</strong><br />

Australia’s first industries. 5 They were originally built for<br />

grinding wheat but in 1827 they were converted into woollen<br />

mills. Wool was a continually expanding industry at this time,<br />

strongly supported by Commissioner Bigge who had been<br />

sent from Britain to inspect the colony in 1819. 6 As historian<br />

Lucy Turnbull observes ‘The wool industry was the fuel that<br />

ignited the economic boom <strong>of</strong> the 1830s’. Wool led pastoralists<br />

to rapidly invade Aboriginal lands in the interior. But<br />

transporting, processing, storing and exporting wool ironically<br />

also fostered <strong>Sydney</strong>’s development. 7 Wool shaped the<br />

fortunes <strong>of</strong> the city: when the first economic bust occurred in<br />

the 1840s the collapse <strong>of</strong> the wool industry played a major part<br />

in the financial crash. When drought hit wool prices, <strong>Sydney</strong>’s<br />

industries took it hard. Many new companies, which had been<br />

established in the previous decade, fell apart. The new mills at<br />

Waterloo were lucky to survive.<br />

Another industry established before 1850 was Hinchcliff’s<br />

Waterloo Mills wool washing establishment set up in 1848<br />

on the Waterloo Dam, which had originally been constructed<br />

by Simeon Lord for his mill (see also Chapter 4). The Hinchcliff<br />

mill was located at what is today the corner <strong>of</strong> Allen and<br />

George streets in Waterloo. 8 Woolwashing was important<br />

for the industry because the wool had to be cleaned <strong>of</strong> the<br />

oily lanolin and dirt before it was exported to Britain or sold<br />

locally. 9 The area continued to be an important centre for<br />

the wool industry into the second half <strong>of</strong> the century, with<br />

continual developments <strong>of</strong> new technologies. One establishment,<br />

Ebsworth’s woolscouring works, was well known for its<br />

technique <strong>of</strong> drying the wool with hot air. 10<br />

50<br />

6.2.2. Phase 2: 1850–1900<br />

The area around Redfern was developed as a working class<br />

residential area in the 1860s, and Alexandria and Waterloo’s<br />

suburbs grew in the latter part <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century. 11 But<br />

the area was not a completely ‘industrial landscape’ early in<br />

this phase. Factories were sparsely spread out around the area.<br />

By 1871 the Hinchliff works were still surrounded by open<br />

ground, and the prime industries at this time were still rurally<br />

based trades. A Health Board Inspector’s 1876 report gave ‘the<br />

impression <strong>of</strong> large parts <strong>of</strong> the area as “semi-rural”, that is,<br />

without large accumulations <strong>of</strong> population and with much<br />

market gardening’. 12<br />

More industries were established in the area in the 1880s.<br />

They were attracted to Alexandria and Waterloo by the flat<br />

landscape, the availability <strong>of</strong> water, the close proximity to the<br />

city and Port Jackson and the railway at Eveleigh. 13 They were<br />

also mainly noxious trades which had either been banned<br />

from the city or were increasingly unacceptable as <strong>Sydney</strong> was<br />

transforming into a business district rather than an industrial<br />

centre.<br />

The South <strong>Sydney</strong> Heritage Study provides a list <strong>of</strong> industries in<br />

the wider South <strong>Sydney</strong> area (Alexandria, Waterloo, Redfern)<br />

in the nineteenth century. It lists forty-three types <strong>of</strong> industry,<br />

including breweries, wool washing, soap works, brickworks,<br />

dairy, market gardens, tanneries, boiling down works, glass<br />

works and the <strong>Sydney</strong> Jam Factory (later known to workers as<br />

‘The Jammy’). 14 At Hinchcliff’s wool washing establishment,<br />

there were approximately one-hundred hands employed,<br />

most <strong>of</strong> whom lived on the estate, and ‘wool was conveyed<br />

to <strong>Sydney</strong> three times a day. 15 The Goodlet and Smith Brickwork’s<br />

on Botany Road, Waterloo was established in 1855 and<br />

covered four to five acres <strong>of</strong> land (now the block between<br />

Epsom and Cressy Streets), producing bricks for <strong>Sydney</strong>’s<br />

rapid expansion. 16 Overall, though, many <strong>of</strong> these industries<br />

© Susannah Frith<br />

were small-scale companies, employing between ten and fifty<br />

men, boys and girls.<br />

The Royal Commission <strong>of</strong> Inquiry into Noxious Trades outlined<br />

the type, condition and practices <strong>of</strong> industries that existed in<br />

1883. Mr James Johnson’s Wool-washing and Fellmongering<br />

in Waterloo carried out ‘the businesses <strong>of</strong> wool-washing,<br />

sorting, pressing, and fellmongering’ in buildings <strong>of</strong> iron and<br />

wood ‘in fair repair’. The place boasted a steam engine with<br />

two boilers, sweating-room and soak-pit, and ‘all other requisites<br />

for a large business’. It employed on average ‘forty men<br />

and six boys’. Two dams supplied water, while the excess water<br />

drained from the surface into a creek and thence into Shea’s<br />

Creek, along with all the ‘refuse’. The works processed 5,000<br />

bales a year, including the wool taken from skins. 17 The Commissioners<br />

were refused entry into the Alderson Tannery so<br />

they were unable to inspect it. A map <strong>of</strong> Waterloo dating from<br />

around 1885 showed approximately fourteen identifiable<br />

industrial sites, including two breweries, three soap works, a<br />

rope works, three wool washes, a dairy, a brickworks, a pottery,<br />

a tallow works and a flour mill on the corner <strong>of</strong> Pitt and Wellington<br />

streets.<br />

The Royal Commission into Noxious Trades also gave some<br />

insight into what it would have been like to live close to such<br />

industries. Witnesses complained <strong>of</strong> the smells from the dyes<br />

in the tanning and leather industries and meat in the slaughterhouses<br />

prominent in the area. Together with smoke from<br />

the chimneys, these stinks created an atmosphere rather<br />

different to the Waterloo we know today. 18 As Scott Cumming<br />

discusses in Chapter 4, many <strong>of</strong> these noxious industries were<br />

based around the Alexandria Canal and washed their waste<br />

straight into it, so the quality <strong>of</strong> the water would have been<br />

appalling.<br />

But these industries also provided much needed employment<br />

in <strong>Sydney</strong>, especially during the hard years <strong>of</strong> the depression<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 1890s, and again in the 1920s. Fitzgerald observes that,<br />

already in the 1860s, 74 per cent <strong>of</strong> Alexandria’s population<br />

were blue collar workers—‘far exceeding the metropolitan<br />

average’, with ‘not a single doctor, clergyman or lawyer’. 19 Cable<br />

and Annable trace the location <strong>of</strong> working class residents in<br />

the areas <strong>of</strong> Alexandria and Waterloo:<br />

In Alexandria in the 1870s those occupants who are<br />

identified as ‘gardeners’ appear to be resident in the<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> Wyndham Road, Buckland Street, Ricketty<br />

Road, Mitchell Road and Garden Street, with dairymen<br />

on Mitchell Road, Wyndham Street and Botany Road.<br />

In the late 1880s…by contrast the area along Barwon<br />

Park Road was devoted to brickworks. 20<br />

According to some, the living conditions for workers were not<br />

very desirable, with many workers living in what were regarded<br />

as crowded slums and as squatters (see also Chapter 7). 21<br />

6.2.3 Phase 3: 1900–1950<br />

In the second half <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century and the beginning<br />

<strong>of</strong> the twentieth century, the types <strong>of</strong> industries in the area did<br />

not vary to great extent. It was not until the 1920s that new<br />

types <strong>of</strong> industries began to appear in the area. Meanwhile,<br />

the market gardens, which had been a huge establishment in<br />

the area up to this period, petered out. 22 These new industries<br />

were on a different scale. They were heavier, they employed<br />

more people, for now workers numbering in the hundreds,<br />

and companies began to expand their factories to accommodate<br />

higher product demand. The turn <strong>of</strong> the century brought<br />

© Susannah Frith<br />

Chapter 6 – From Tanning to Planning<br />

Witnesses complained <strong>of</strong> the smells<br />

from the dyes in the tanning and<br />

leather industries, and meat in the<br />

slaughterhouses prominent in the<br />

area. Together with smoke from<br />

the chimneys, these stinks created<br />

an atmosphere rather different to<br />

the Waterloo we know today.<br />

great changes and development for industry, as the manufacturing<br />

sector experienced rapid growth and the further<br />

extension <strong>of</strong> heavy industry. 23<br />

Australian industry benefited greatly during the First World<br />

War from the guaranteed sale <strong>of</strong> wool and beef to the British<br />

government for the duration <strong>of</strong> the war. 24 During the postwar<br />

boom <strong>of</strong> the 1920s, large-scale industries were established and<br />

many more factories built. This development brought many<br />

new people to Alexandria and Waterloo in search <strong>of</strong> work, so<br />

this period is also marked by the rapid growth <strong>of</strong> the industrial<br />

suburbs. The Depression which hit Australia between 1929-<br />

1933 slowed the development <strong>of</strong> industry down only slightly,<br />

and it had recovered a roaring pace at the outbreak <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Second World War. By 1943, the Municipality <strong>of</strong> Alexandria<br />

proudly boasted that it contained 550 factories, and was ‘the<br />

largest industrial municipality in Australia’. 25 Peter Spearritt,<br />

however, estimates the number <strong>of</strong> factories to be 342 in 1944,<br />

employing 22,238 workers; with ‘one half <strong>of</strong> the suburb …<br />

occupied by large industrial concerns’. 26<br />

The Second World War also had a significant effect on<br />

Waterloo and Alexandria. Most industries devoted all their<br />

resources to the war effort, suspending their own production<br />

to take up the manufacture <strong>of</strong> rifle butts and stocks or other<br />

wartime products, depending on their plant and equipment.<br />

Some companies managed to continue to make their own<br />

products alongside their war effort work. In order to do their<br />

bit, Felt & Textiles <strong>of</strong> Australia Pty. Ltd. had to abandon a<br />

section <strong>of</strong> their activities and were forced to compromise on<br />

the quality <strong>of</strong> their products for the duration <strong>of</strong> the war. 27 Slazengers<br />

(Australia) Pty. Limited, a sporting goods company is<br />

a good example <strong>of</strong> the kind <strong>of</strong> sacrifice and effort that was<br />

made by industries in the war (though the contracts could also<br />

be lucrative). They ‘sought and obtained one <strong>of</strong> the earliest<br />

contracts for pre-fabricated huts’, while also making rifle<br />

furniture as well as sporting equipment to encourage health<br />

and fitness in the armed forces. 28<br />

While the majority <strong>of</strong> working people who lived in the area<br />

laboured in its factories, ‘only one-tenth <strong>of</strong> the factory labour<br />

force lived in the area’. 29 This means that industry was drawing<br />

huge numbers to work each day from outside the area. One<br />

factory that prided itself in employment <strong>of</strong> local people<br />

was Hadfields Steel Works Limited, where many <strong>of</strong> the five<br />

hundred employees in 1943 were locals. 30 The size <strong>of</strong> industries<br />

grew at a considerable rate at this time and average<br />

employee numbers grew to between two and four hundred.<br />

Metters Limited employed a massive 2,500 staff.<br />

51