HISTORY INTO ART AND ANTHROPOLOGY - Snite Museum of Art ...

HISTORY INTO ART AND ANTHROPOLOGY - Snite Museum of Art ...

HISTORY INTO ART AND ANTHROPOLOGY - Snite Museum of Art ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

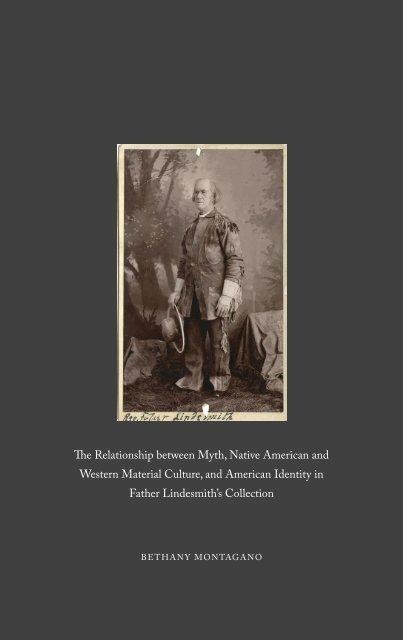

The Relationship between Myth, Native American and<br />

Western Material Culture, and American Identity in<br />

Father Lindesmith’s Collection<br />

BETHANY MONTAGANO<br />

On August 14, 1882, U.S. Army chaplain Eli Washington John Lindesmith left<br />

Fort Keogh to “hunt” for an Indian skeleton 1 . He knew where to look, walking his<br />

Indian pony along the north side <strong>of</strong> the Yellowstone River in Montana Territory<br />

to a sacred site that the Lakota dubbed Big Cooley. Later, Father Lindesmith<br />

wrote, “On the west side about half-way up, under a cedar tree, whereon had been<br />

placed the dead body, but now scattered on the ground, I found this jaw bone and<br />

two other bones, and this piece <strong>of</strong> board [on] which the body had been placed.” 2<br />

He made <strong>of</strong>f with a jawbone and a forearm bone still tethered to the burial plank<br />

belonging to an infant. 3<br />

Lindesmith recorded this as a singular find; it represented the 644th object in his<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> Western, Native American, military, natural history, personal, and<br />

religious artifacts and samples, most <strong>of</strong> which he amassed during his 1880 to 1891<br />

tenure as the first Catholic chaplain in the U.S. Army commissioned during peacetime.<br />

4 Although he acquired many items legitimately—ones given to him by friends,<br />

paid for in cash, or traded for with luxury items such as bacon 5 —he also obtained<br />

other items illegitimately. 6<br />

Father Lindesmith left behind fastidious notes about how, when, why, and from<br />

whom he obtained his items, what he considered their historical and/or cultural<br />

significance, and exactly what he paid for the ones he purchased. A close examination<br />

<strong>of</strong> those notes and various objects in the collection reveals something about<br />

the extent to which cultural stereotypes, romantic appraisals <strong>of</strong> the American West,<br />

identity, race, religion, Native participation, and the market for Native American<br />

cultural goods affected the practice <strong>of</strong> misappropriation in the West during the late<br />

nineteenth century (fig. 5, opposite).<br />

Through the prism <strong>of</strong> misappropriation, it appears that Lindesmith was not simply<br />

participating in benign forms <strong>of</strong> curiosity collecting; indeed, he was purposely<br />

accumulating a vast array <strong>of</strong> disparate objects to validate his Western experience.<br />

Among these were beaver and grizzly-bear fur coats, arms and swords (fig. 6)<br />

associated with several famous Indian battles, George Armstrong Custer’s field<br />

trunk, one <strong>of</strong> Captain Myles Keogh’s rib bones, saddles, lariats, Indian guns,<br />

scalping knives, war clubs, tin cans, and even coveredwagon tarps. His cataloguing<br />

notes reveal the degree to which he regarded these artifacts as a means <strong>of</strong><br />

authenticating not just the makers’ identities but also his own identity (fig. 7). As a<br />

U.S. Army chaplain, collector, and museum benefactor, Lindesmith contributed to<br />

and helped perpetuate the myth <strong>of</strong> the American West. 7<br />

Fig. 5: Father Lindesmith in his leather outfit and broad brim hat from Montana Territory; CHCUSPCA<br />

36 37