HISTORY INTO ART AND ANTHROPOLOGY - Snite Museum of Art ...

HISTORY INTO ART AND ANTHROPOLOGY - Snite Museum of Art ...

HISTORY INTO ART AND ANTHROPOLOGY - Snite Museum of Art ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

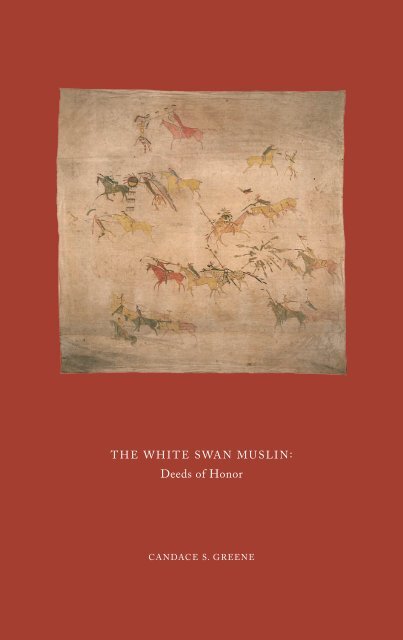

THE WHITE SWAN MUSLIN:<br />

Deeds <strong>of</strong> Honor<br />

C<strong>AND</strong>ACE S. GREENE<br />

In recent decades, we have become increasingly aware that the meanings <strong>of</strong> objects<br />

are never static. Views <strong>of</strong> them shift as they change locale and move through a<br />

social world, employed by different people for different purposes. The anthropologist<br />

Igor Kopyt<strong>of</strong>f introduced the idea that objects have “cultural biographies”; this<br />

has proven to be a productive way to think about objects in museums—exploring<br />

the hands through which they have passed and the various meanings they have<br />

assumed over time. 1<br />

Kopyt<strong>of</strong>f ’s approach has been applied most successfully in considerations <strong>of</strong> the life<br />

<strong>of</strong> an object after it has left the person who made it, particularly when the maker<br />

is from a community without a tradition <strong>of</strong> literacy; this is the method’s major<br />

limitation. Often, considerably more information is available about the object’s<br />

subsequent owners than about its creator. Such is the case with what is known as<br />

the White Swan muslin, a large sheet <strong>of</strong> fabric in the Father Lindesmith collection<br />

at the <strong>Snite</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> that is covered with paintings <strong>of</strong> war scenes by a<br />

Native American artist. Dynamically executed images <strong>of</strong> men and horses race amid<br />

flying bullets and arrows. The clash <strong>of</strong> arms, the glorious charge, and the uncertain<br />

outcome all impart drama to the stained and aged cloth, which the collector called<br />

a “blanket.” This essay examines the context within which the White Swan muslin<br />

was created and focuses on the early part <strong>of</strong> its “life.”<br />

THE LINDESMITH MUSLIN<br />

In August 1889, Father Lindesmith bought several items, including a pictographic<br />

muslin, from the Custer Store at the Crow Agency in Montana. He placed a tag<br />

on the object reading “Crow Indian Blanket. I bought it on the Big Horn River,<br />

Montana for 6.00” and noted, in both his account book and a memorandum <strong>of</strong> that<br />

year, “Bought a Crow Indian Blanket, Custer Store, 1889.” Lindesmith carefully<br />

recorded specifics about his purchasing <strong>of</strong> objects but provided minimal information<br />

about other relevant aspects <strong>of</strong> his acquisitions. As a result, in this case, several<br />

questions arise: Who painted the muslin? What motivated him to paint it? How<br />

did it come to be available for purchase in the Custer Store? Fortunately, careful<br />

study <strong>of</strong> the object itself can provide some answers to these tantalizing questions.<br />

We know, for a start, that the Crow warrior White Swan painted the muslin. His<br />

identity was established by recognizing similarities in style and content to other<br />

works he is known to have made. At least fifteen paintings have been attributed<br />

to him, linked to one another by the many scenes they share and to White Swan<br />

by the few for which his name is definitively known. Others likely remain to<br />

be discovered. With that many examples spanning a number <strong>of</strong> years, a picture<br />

emerges <strong>of</strong> White Swan as a pr<strong>of</strong>essional artist who created works for sale. Like<br />

54 55