Electronic Discovery and Computer Forensics Case List - Kroll Ontrack

Electronic Discovery and Computer Forensics Case List - Kroll Ontrack

Electronic Discovery and Computer Forensics Case List - Kroll Ontrack

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

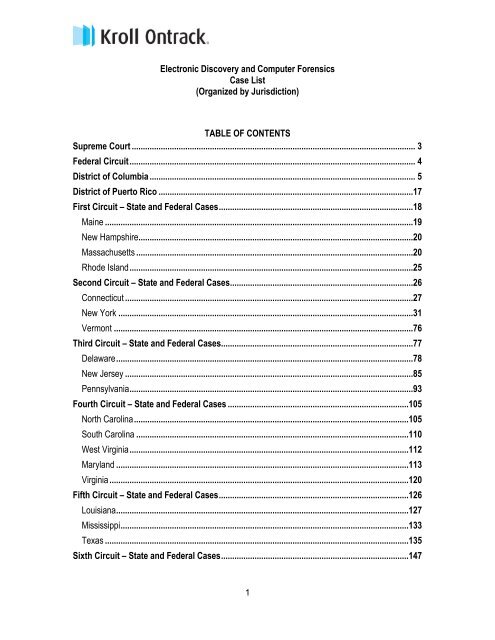

<strong>Electronic</strong> <strong>Discovery</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Computer</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong><br />

<strong>Case</strong> <strong>List</strong><br />

(Organized by Jurisdiction)<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Supreme Court ............................................................................................................................... 3<br />

Federal Circuit ................................................................................................................................ 4<br />

District of Columbia ....................................................................................................................... 5<br />

District of Puerto Rico ..................................................................................................................17<br />

First Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s .......................................................................................18<br />

Maine ..........................................................................................................................................19<br />

New Hampshire ...........................................................................................................................20<br />

Massachusetts ............................................................................................................................20<br />

Rhode Isl<strong>and</strong> ...............................................................................................................................25<br />

Second Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s ..................................................................................26<br />

Connecticut .................................................................................................................................27<br />

New York ....................................................................................................................................31<br />

Vermont ......................................................................................................................................76<br />

Third Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s......................................................................................77<br />

Delaware .....................................................................................................................................78<br />

New Jersey .................................................................................................................................85<br />

Pennsylvania ...............................................................................................................................93<br />

Fourth Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s .................................................................................105<br />

North Carolina ...........................................................................................................................105<br />

South Carolina ..........................................................................................................................110<br />

West Virginia .............................................................................................................................112<br />

Maryl<strong>and</strong> ...................................................................................................................................113<br />

Virginia ......................................................................................................................................120<br />

Fifth Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s .....................................................................................126<br />

Louisiana ...................................................................................................................................127<br />

Mississippi .................................................................................................................................133<br />

Texas ........................................................................................................................................135<br />

Sixth Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s ....................................................................................147<br />

1

Kentucky ...................................................................................................................................147<br />

Michigan ....................................................................................................................................149<br />

Ohio ..........................................................................................................................................158<br />

Tennessee ................................................................................................................................167<br />

Seventh Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s ...............................................................................170<br />

Illinois ........................................................................................................................................172<br />

Indiana ......................................................................................................................................189<br />

Wisconsin ..................................................................................................................................194<br />

Eighth Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s .................................................................................198<br />

Arkansas ...................................................................................................................................199<br />

Iowa ..........................................................................................................................................200<br />

Minnesota .................................................................................................................................201<br />

Missouri .....................................................................................................................................208<br />

Nebraska ...................................................................................................................................211<br />

North Dakota .............................................................................................................................213<br />

South Dakota ............................................................................................................................214<br />

Ninth Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s ...................................................................................216<br />

Alaska .......................................................................................................................................219<br />

Arizona ......................................................................................................................................219<br />

California ...................................................................................................................................221<br />

Hawaii .......................................................................................................................................251<br />

Idaho .........................................................................................................................................252<br />

Montana ....................................................................................................................................252<br />

Oregon ......................................................................................................................................253<br />

Nevada ......................................................................................................................................253<br />

Washington ...............................................................................................................................256<br />

Tenth Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s ...................................................................................262<br />

Colorado ...................................................................................................................................264<br />

Kansas ......................................................................................................................................269<br />

New Mexico ..............................................................................................................................280<br />

Oklahoma ..................................................................................................................................281<br />

Utah ..........................................................................................................................................283<br />

Eleventh Circuit – State <strong>and</strong> Federal <strong>Case</strong>s ..............................................................................288<br />

Alabama ....................................................................................................................................289<br />

2

Florida .......................................................................................................................................290<br />

Georgia .....................................................................................................................................304<br />

Other Jurisdictions .....................................................................................................................309<br />

Court of International Trade ......................................................................................................309<br />

Federal Claims Court ................................................................................................................309<br />

United States Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals ...................................................................311<br />

United States Tax Court ............................................................................................................311<br />

Virgin Isl<strong>and</strong>s.............................................................................................................................312<br />

Other Countries ...........................................................................................................................312<br />

Engl<strong>and</strong> .....................................................................................................................................312<br />

Supreme Court<br />

� City of Ontario v. Quon, 2010 WL 2400087 (U.S. June 17, 2010). In this appeal addressing an<br />

employer’s search of an employee’s text messages, the United States Supreme Court found the<br />

search to be reasonable, but declined to issue a “broad holding concerning employees’ privacy<br />

expectations vis-à-vis employer provided technological equipment.” Addressing the reasoning for<br />

the search (i.e., review of the text message transcripts), the court found the City possessed a<br />

“legitimate interest” in ensuring employees were not forced to pay for overages out-of-pocket <strong>and</strong><br />

that the City was not paying for personal communications. In regard to the search itself, the court<br />

found the City’s method of reviewing the text message transcripts to be reasonable as it was an<br />

“efficient <strong>and</strong> expedient way” to determine the nature of the overages. In support of this decision,<br />

the court noted the steps taken to reduce the search intrusiveness, such as the restriction of the<br />

search date range <strong>and</strong> limitation of transcript review to messages sent by the employee while onduty.<br />

The court also discussed that the employee should have understood or anticipated that it<br />

might be necessary for the City to audit the pager messages to determine whether the pagers were<br />

being appropriately used, or to assess the SWAT team’s performance in emergency situations (the<br />

primary purpose for the pager issuance). Finally, the court determined the Ninth Circuit erred in<br />

suggesting the City could have used “less intrusive means” to make the overage determinations<br />

<strong>and</strong> also held that the search was not rendered unreasonable by the assumption that Arch<br />

Wireless violated the Stored Communications Act by turning over the transcripts.<br />

� Arthur Andersen LLP v. United States, 125 S.Ct. 2129 (U.S. 2005). After becoming of aware of<br />

Enron’s financial difficulties, Arthur Andersen told partners working on the Enron team to ensure<br />

compliance with Andersen’s document retention policy. Following that meeting, substantial paper<br />

<strong>and</strong> electronic documents were destroyed. At trial, the jury found Arthur Andersen guilty of<br />

knowingly, intentionally <strong>and</strong> corruptly persuading employees to withhold documents from a<br />

regulatory proceeding. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the decision. On appeal, the Supreme Court<br />

reversed <strong>and</strong> held that the jury instructions were flawed. The court declared that, under normal<br />

circumstances, a manager could instruct employees to comply with a valid document retention<br />

policy, even though the policy was partly designed to prevent others (including the government)<br />

from accessing certain information. The court found that the jury instructions erroneously implied<br />

3

the jury did not have “to find any nexus between the "persua[sion]" to destroy documents <strong>and</strong> any<br />

particular proceeding.” The court further stated that a "‘knowingly . . . corrup[t] persaude[r]’ cannot<br />

be someone who persuades others to shred documents under a document retention policy when<br />

he does not have in contemplation any particular official proceeding in which those documents<br />

might be material.”<br />

� Oppenheimer Fund, Inc. v. S<strong>and</strong>ers, 437 U.S. 340 (1982). “[W]e do not think a defendant should<br />

be penalized for not maintaining his records in the form most convenient to some potential future<br />

litigants whose identity <strong>and</strong> perceived needs could not have been anticipated.” Where the expense<br />

of creating computer programs that would locate the desired data was the same for both parties,<br />

the court ordered that the party seeking the information must bear the cost of production.<br />

Federal Circuit<br />

� In re Ricoh Co. Ltd. Patent Litig., 661 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2011). Following a court of appeals<br />

affirmation of a district court’s order granting the defendant summary judgment in a patent<br />

infringement suit, the plaintiff sought review of several items in a $938,957 taxation award. Namely,<br />

the plaintiff disputed costs awarded for using a third-party document database service to produce<br />

e-mail <strong>and</strong> fees for generically itemized exemplification <strong>and</strong> copying. With regard to the document<br />

database, the court found that the review database was used as the exclusive form of document<br />

production—rather than for the convenience of the parties—<strong>and</strong> was properly taxable. However,<br />

the court reversed the original award of $234,702 based on a finding that the parties contractually<br />

agreed to divide costs before leveraging the service. Reviewing the defendant’s costs, the court<br />

found that vague phrases such as "document production" that were frequently itemized did not<br />

represent a reasonably accurate calculation of documents copied for, or tendered by, the opposing<br />

party. Accordingly, the court vacated the $322,702 award for copying fees, which was rem<strong>and</strong>ed to<br />

district court.<br />

� Jicarilla Apache Nation v. United States, 60 Fed. Cl. 413 (Fed. Cir. 2004). Alleging that the<br />

government mismanaged trust funds, the plaintiff moved for a confidentiality agreement <strong>and</strong><br />

protective order. Determining that good cause existed for approval <strong>and</strong> entry of the order, the court<br />

issued specific procedures for the production of electronic records. In defining records that needed<br />

to be produced, the court included computer or network activity logs, voice-mail, data, databases,<br />

images, e-mails, spreadsheets, <strong>and</strong> metadata. The court also determined that if the parties<br />

provided access to electronic data rather than making actual copies of it, the parties should<br />

designate which electronic records are available for production by categorizing them in writing by<br />

record, category, search parameters, or other reasonable methods. In addressing production<br />

format, the court directed the parties to produce records “in the format in which that party routinely<br />

uses or stores them, provided that electronic records shall be produced along with available<br />

technical information necessary for access or use.” If the requesting party is unable to access or<br />

use an electronic record, the court indicated it may request that the responding party provide a<br />

paper version of or underlying source data for the electronic record.<br />

� First USA Bank v. PayPal, Inc., 76 Fed.Appx. 935 (Fed. Cir. 2003). In a patent infringement<br />

action, the plaintiff subpoenaed the defendant’s former chief executive officer, specifically<br />

requesting the court to compel his deposition <strong>and</strong> to require him to produce his laptop computer for<br />

forensic inspection. The former-CEO had used the computer while employed by the defendant <strong>and</strong><br />

subsequently purchased it from the defendant when he left its employ. Despite objection, the<br />

magistrate judge ordered the former-CEO to be available for deposition <strong>and</strong> approved a search<br />

4

protocol. The search protocol allowed electronic evidence consultants to create a forensic copy of<br />

the computer’s hard drive, identify any potentially relevant documents, <strong>and</strong>, if such documents<br />

were found <strong>and</strong> identified, allow the former-CEO to create a privilege log. The district court affirmed<br />

the magistrate’s order <strong>and</strong> former-CEO appealed. The appellate court dismissed the former-CEO’s<br />

appeal of the lower court’s non-final interlocutory discovery order.<br />

District of Columbia<br />

� Williams v. Dist. of Columbia, 2011 WL 3659308 (D.D.C. Aug. 17, 2011). In this wrongful<br />

termination litigation, the defendant requested the return of an allegedly privileged e-mail<br />

containing a 104-page document related to the plaintiff’s termination. Although the defendant<br />

initially requested the immediate return of the privileged documents, the plaintiff never responded<br />

<strong>and</strong> the defendant took no further action for more than two years until the plaintiff identified the email<br />

as an exhibit for trial. Reviewing the defendant’s discovery conduct, the court determined it did<br />

not meet the burden required to demonstrate that reasonable steps were taken to prevent or<br />

remedy inadvertent disclosure. Specifically, the court took issue with the defendant’s unsworn<br />

statements from counsel — who had not been involved with the case at the time of disclosure —<br />

<strong>and</strong> determined that the generic statements failed to sufficiently detail the reasonableness of its<br />

review procedures including its methodology, the total number of documents reviewed or any time<br />

pressure imposed by the plaintiff’s discovery requests. Further, the court found that the defendant’s<br />

two year stagnancy did not constitute reasonable attempts to rectify its error. Citing each failure as<br />

independent ground for denial, the court denied the motion to exclude <strong>and</strong> waived privilege.<br />

� DL v. District of Columbia, No. 05-1437 (RCL) (D.D.C. May 9, 2011). In this class action dispute<br />

concerning free public education under the Individuals with Disabilities <strong>and</strong> Education Act, the<br />

defendant filed a motion to reconsider the grant of the plaintiff’s motion to compel production <strong>and</strong><br />

the court’s determination that privilege was waived for all e-mails yet to be produced. On the day<br />

the court was scheduled to issue its opinion, the plaintiffs’ counsel informed the court that the<br />

defendants had produced thous<strong>and</strong>s of e-mails days before trial <strong>and</strong> were continuing to "document<br />

dump" after trial concluded. The defense counsel claimed the District was understaffed, committed<br />

supplemental searches that yielded tens of thous<strong>and</strong>s of additional e-mails, discovery was<br />

voluminous <strong>and</strong> there were not "enough bodies" to complete the process before trial. Denying the<br />

defendants’ motion, the court cited the "repeated, flagrant, <strong>and</strong> unrepentant failures to comply with<br />

Court orders" <strong>and</strong> "discovery abuse so extreme as to be literally unheard of in this Court." The<br />

court also repeatedly noted the defendants’ failure to adhere to the discovery framework provided<br />

by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure <strong>and</strong> advised the defendants to invest time spent "anklebiting<br />

the plaintiffs" into shaping up its own discovery conduct.<br />

� United States v. Halliburton Co., 2011 WL 208301 (D.D.C. Jan. 24, 2011). In this qui tam action<br />

alleging fraud perpetrated against the United States, the plaintiff requested an order from the court<br />

requiring the defendants to search the electronic data of all employees who were copied on e-mails<br />

that were previously produced. The defendants argued that this search would encompass an<br />

additional 35 custodians that possess an average of 15 to 20 GB of data <strong>and</strong> that it would take two<br />

to ten days per custodian for the collection process before review could occur. Denying the<br />

plaintiff’s request for additional searches, the court noted that the defendants had already spent “a<br />

king’s ransom” of $650,000 on discovery <strong>and</strong> had produced more than 2 million paper documents,<br />

thous<strong>and</strong>s of spreadsheets <strong>and</strong> more than half a million e-mails. Further, the court determined the<br />

plaintiff failed to demonstrate that any e-mails not produced were crucial to her claims.<br />

5

� Covad Commc’ns Co. v. Revonet, Inc., 2010 WL 1233501 (D.D.C. Mar. 31, 2010). In this<br />

ongoing secrets misappropriation litigation, the court considered six of nine discovery motions both<br />

parties had filed. In particular, the court addressed the plaintiff’s motion to compel production of<br />

35,000 e-mails in native file format including metadata, following the defendant’s production of<br />

those e-mails as hard-copy printouts. Addressing this motion, the court noted that it was bound by<br />

Fed.R.Civ.P. 26(b)(2)(C)(iii), which requires a limit of discovery if “the burden or expense of the<br />

proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit” <strong>and</strong> explained that the parties had “bigger fish to<br />

fry” in the interest of judicial expediency. Based on this <strong>and</strong> the plaintiff’s failure to demonstrate a<br />

specific need for the e-mail metadata, the court held that the production of the hard copies in native<br />

format in this stage of the dispute was not necessary <strong>and</strong> denied the plaintiff’s motion.<br />

� Trustees of Elec. Workers Local No. 26 Pension Trust Fund v. Trust Fund Advisors, Inc.,<br />

2010 WL 558719 (D.D.C. Feb. 12, 2010). In this litigation, the defendants filed a renewed motion to<br />

compel documents withheld by the plaintiffs under the claim of privilege. First, the court addressed<br />

whether privilege existed in the first place by examining the parties involved <strong>and</strong> determined<br />

privilege existed despite the presence of two consultants at the meetings, since they became<br />

integral members of the team assigned to deal with litigation <strong>and</strong> legal strategies. Next, the court<br />

determined whether privilege was waived or “forfeited,” noting that Fed.R.Evid. 502 abolished the<br />

“dreaded subject-matter waiver.” Thus, the defendants’ argument that the disclosure of nonprivileged<br />

information should constitute a waiver of privileged information of the same subject<br />

matter was “flat out wrong,” since the question is whether the information, both disclosed <strong>and</strong><br />

undisclosed, shares the same subject matter <strong>and</strong> ought in fairness to be considered together.<br />

Based on this analysis, the court denied the defendants’ arguments that privilege was waived <strong>and</strong><br />

ordered the plaintiffs to provide documents marked as privilege for an in camera review.<br />

� Amobi v. District of Columbia Dep’t of Corr., 2009 WL 4609593 (D.D.C. Dec. 8, 2009). In this<br />

litigation, the court addressed the parties’ motions related to the production of a memor<strong>and</strong>um<br />

created by an attorney for the defendants. The defendants argued the disclosure was inadvertent<br />

<strong>and</strong> steps were taken to rectify the error immediately, whereas the plaintiffs argued the<br />

memor<strong>and</strong>um was either not privilege-protected or privilege had been waived. After determining<br />

that the document was protected by the work product doctrine, the court used the three-part test<br />

set forth in Fed.R.Evid. 502(b) <strong>and</strong> found privilege was waived. In support of this finding, the court<br />

cited the defendants’ failure to explain the methods used to prevent disclosure in order to establish<br />

the magnitude of the error. The court reasoned that "defendants’ failure to take reasonable efforts<br />

to prevent the disclosure in the first place doom[ed] their reliance on the rule." However, the court<br />

refused to endorse the plaintiffs’ argument that lawyers could never make inadvertent mistakes,<br />

claiming that would "gut [Rule 502] like a fish."<br />

� Covad Commc’ns. Co. v. Revonet, Inc., 2009 WL 2595257 (D.D.C. Aug. 25, 2009). In this<br />

ongoing trade secrets misappropriation litigation, the plaintiff sought compliance with the court’s<br />

December 2008 order granting a motion to compel discovery. See Covad Comm. Co. v. Revonet,<br />

Inc., 2008 WL 5377698 (D.D.C. Dec. 24, 2008). The plaintiff argued production was incomplete,<br />

the production format was noncompliant <strong>and</strong> that a discrepancy existed between certain e-mails<br />

produced in both native format <strong>and</strong> hard copy. The court first deferred addressing the production<br />

issue until the results of a forensic search of relevant electronically stored information were<br />

discussed at a later hearing. Turning to the e-mail discrepancy, the court ordered the defendant to<br />

produce all missing e-mails in native format. Regarding the remaining production disputes, the<br />

court noted the parties were working to resolve the issues <strong>and</strong> ordered the defendant to answer<br />

whether the documents were either produced in native format or if they would be produced at all.<br />

6

Finally, the court expressed displeasure with data downgrading stating, "taking an electronic<br />

document . . . printing it, cutting it up, <strong>and</strong> telling one’s opponent to paste it back together again,<br />

when the electronic document can be produced with a keystroke, is madness." Ultimately, the court<br />

stayed action on the motion pending the defendant’s responses to the questions posed.<br />

� In re Rail Freight Fuel Surcharge Antitrust Litig., 2009 WL 1904333 (D.D.C. July 2, 2009). In<br />

this antitrust action, the defendants moved for bifurcated discovery between class certification <strong>and</strong><br />

merits discovery. The defendants contended that bifurcated discovery was possible through the<br />

use of search terms to effectively isolate electronically stored information (ESI) relevant to<br />

"certification" but not "merits" discovery. The defendants argued that bifurcated discovery would<br />

facilitate early resolution of the certification issue <strong>and</strong> reduce the burden of subsequent merits<br />

discovery. In opposition, the plaintiffs argued that certification <strong>and</strong> merits discovery are<br />

indistinguishable as evidence regarding the merits was also crucial to certification. The plaintiffs<br />

also argued that bifurcated discovery would forced the defendants to conduct document review to<br />

classify ESI as either class certification or merits discovery as no search engine could effectively<br />

distinguish between the two, <strong>and</strong> thus simultaneous discovery would be more efficient <strong>and</strong> cost<br />

effective. Magistrate Judge Facciola agreed with the plaintiffs’ contention that the issues involved in<br />

certification <strong>and</strong> merits discovery were closely intertwined. The court expressed doubt that the<br />

defendants’ could effectively distinguish between the two categories of documents, noting that the<br />

defendants did not propose exactly how the lawyers will "create a search engine so refined <strong>and</strong><br />

exquisite." The court also held that bifurcation would delay the proceedings <strong>and</strong> hinder judicial<br />

economy, citing the delays <strong>and</strong> costs associated with continued need for judicial supervision <strong>and</strong><br />

the increased number of disputes over discovery in a bifurcated case. Accordingly, the court<br />

denied the motion for bifurcated discovery.<br />

� Covad Commc’ns. Co. v. Revonet Inc., 2009 WL 1472345 (D.D.C. May 27, 2009). In this<br />

ongoing trade secrets misappropriation litigation, the plaintiff sought forensic images of the<br />

defendant’s drives <strong>and</strong> computers as well as forensic searches of its database <strong>and</strong> e-mail servers.<br />

The defendant argued that its servers were too fragile for forensic images <strong>and</strong> that imaging<br />

constituted an undue burden. The defendant also objected to the forensic search of its servers,<br />

claiming it may reveal information that the defendant is obliged by contract to keep confidential.<br />

Disregarding the defendant’s arguments, the court granted the plaintiff’s request for forensic<br />

imaging, finding the imaging would not stress the servers any more than day-to-day use. The court<br />

also ordered the forensic search of the defendant’s servers, stating that no alternative way existed<br />

<strong>and</strong> that any confidential material could be safeguarded by a protective order. Regarding the e-mail<br />

servers, the court determined insufficient authority existed to conclude ESI deficiency allegations<br />

automatically warranted forensic searches. The court reserved decision on whether forensic<br />

examination was appropriate until the plaintiff’s expert’s report was submitted. The court also<br />

ordered a comparison between servers to determine what data existed on non-operational servers<br />

that did not exist on the remaining operational one.<br />

� Asarco, Inc. v. United States Envtl. Prot. Agency, 2009 WL 1138830 (D.D.C. Apr. 28, 2009). In<br />

this environmental litigation, the plaintiff filed a motion to take discovery. The plaintiff contended<br />

that the defendant’s keyword search was conducted in bad faith, as evidenced by the fact it used<br />

only one search term. Finding the plaintiff’s argument persuasive, the court ordered an additional<br />

keyword search utilizing four additional key terms. Notably, the court stated that "keyword searches<br />

are no longer the favored methodology." The court concluded by recommending summary<br />

judgment on the merits in favor of the defendant after the second search is completed, determining<br />

that there is no genuine issue of material fact whether additional defendant data exist.<br />

7

� Newman v. Borders, Inc., 2009 WL 931545 (D.D.C. Apr. 6, 2009). In this racial discrimination<br />

litigation, the plaintiff requested an additional Fed.R.Civ.P. 30(b)(6) deposition seeking information<br />

about the defendant’s e-mail retention policy. Frustrated with the high costs <strong>and</strong> time spent on<br />

discovery that the court determined "will dwarf the potential recovery," the court denied the<br />

plaintiff’s request <strong>and</strong> ordered the submission of an affidavit after determining a party’s document<br />

retention policy was discoverable. The affidavit was to address the defendant’s e-mail systems,<br />

deletion policies <strong>and</strong> search efforts.<br />

� D’Onofrio v. SFX Sports Group, Inc., 2009 WL 859293 (D.D.C. Apr. 1, 2009). In this ongoing<br />

wrongful termination litigation, the defendants agreed to provide the plaintiff’s counsel with attorney<br />

notes taken by the defendants under certain conditions. Taking exception to these conditions, the<br />

plaintiff’s counsel argued the plaintiff should be granted access to the attorney notes for relevancy<br />

determinations. Magistrate Judge John M. Facciola granted the motion in part, finding the<br />

defendants were allowing access to these documents for efficiency’s sake not because the plaintiff<br />

was entitled to the documents. The court also noted that it is "difficult to unlearn something once it<br />

is learned," <strong>and</strong> therefore the plaintiff should not be allowed access to the privileged documents.<br />

Finally, the court agreed with the plaintiff that there is no need for the plaintiff’s expert to confer with<br />

the defendants’ expert regarding methodology prior to conducting sampling of the documents.<br />

� In re Fannie Mae Sec. Litig., 2009 WL 21528 (C.A.D.C. Jan. 6, 2009). In this litigation, the Office<br />

of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO), a non-party, appealed the district court’s order<br />

finding it in contempt for failing to comply with a discovery d+eadline in a stipulated scheduling<br />

order. OFHEO argued that the defendant’s decision to supply four hundred keyword terms was<br />

outside the scope of “appropriate search terms,” thereby extending the time needed to comply with<br />

its production requirements. However, aware of the deadlines, OFHEO sought several discovery<br />

extensions, hired 50 contract attorneys <strong>and</strong> spent over $6 million – 9% of the agency’s entire<br />

annual budget – to comply with the defendants’ discovery requests. Finding OFHEO’s efforts<br />

legally insufficient, the court compared its treatment of the discovery deadlines as “movable goal<br />

posts” <strong>and</strong> directed OFHEO to supply documents withheld for privilege that were not logged by the<br />

deadline as a sanction for their discovery misconduct. However, the court ruled that any privileged<br />

documents that are produced <strong>and</strong> identified as such will be promptly returned to OFHEO.<br />

� Covad Comm. Co. v. Revonet, Inc., 2008 WL 5377698 (D.D.C. Dec. 24, 2008). In this trade<br />

secrets misappropriation litigation, the plaintiff moved to compel the defendant to reproduce emails<br />

in native format that were previously produced in hard copy. Having been written prior to the<br />

effective date of the amendments to the Federal Rules, the plaintiff’s document production request<br />

did not explicitly include electronically stored information <strong>and</strong> failed to request a particular format<br />

for production. Magistrate Judge Facciola held that both parties played with fire by producing <strong>and</strong><br />

accepting documents in hard-copy form, as they were not reasonably kept in hard copy form in the<br />

ordinary course of business. Therefore, Judge Facciola ordered the defendant to produce the<br />

requested information in native format on a CD <strong>and</strong> split the costs of privilege review (capped at<br />

$4,000) between the parties. Judge Facciola concluded by stating that, “Two thous<strong>and</strong> dollars is<br />

not a bad price for the lesson that the courts have reached the limits of their patience with having to<br />

resolve electronic discovery controversies that are expensive, time-consuming, <strong>and</strong> so easily<br />

avoided by the lawyers’ conferring with each other on such a fundamental question as the format of<br />

their productions of electronically stored information.”<br />

� D’Onofrio v. Sfx Sports Group, Inc., 2008 WL 4737202 (D.D.C. Oct. 29, 2008). In this<br />

employment discrimination litigation, the defendants filed several motions, including a motion for<br />

leave to designate an expert to design a search protocol. Previously, the court stated the lawyers<br />

8

should rely on IT professionals to create a protocol that was easily understood. After the<br />

defendants proposed a highly technical search protocol, the court decided to create one of its own<br />

that included: search parameters <strong>and</strong> locations, time limits <strong>and</strong> a requirement that the defendants<br />

must restore newly discovered ESI.<br />

� United States v. O’Keefe, 2008 WL 3850658 (D.D.C. Aug. 19, 2008). In this criminal prosecution,<br />

the co-defendant sought further discovery, including Department of State e-mails, communications<br />

memor<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> post indictment analyses. The government refused to provide this information<br />

arguing the requested documents would necessarily result in work product disclosure <strong>and</strong> not be<br />

discoverable. Finding defendant’s response equivocal, Magistrate Judge John M. Facciola ordered<br />

the government to search for documents that fall within the discovery request <strong>and</strong> to produce them.<br />

Citing Rule 26(b)(5) of the Fed.R.Civ.P., Judge Facciola required the government to create a<br />

privilege log of documents withheld from production, explicitly describing documents so as to<br />

prevent the necessity of in camera review. See also United States v. O’Keefe, 2008 WL 449729<br />

(D.D.C. Feb. 18, 2008).<br />

� Citizens for Responsibility <strong>and</strong> Ethics in Wash. v. Executive Office of the President, 2008 WL<br />

2932173 (D.D.C. July 29, 2008). In this ongoing litigation alleging improper deletion of White<br />

House e-mails, the plaintiffs sought an order requiring the defendants to recover <strong>and</strong> restore<br />

certain electronic communications created <strong>and</strong>/or received within the White House. Previously,<br />

Magistrate Judge John M. Facciola recommended the Court order the defendants to search the<br />

workstations of employees during the time period at issue <strong>and</strong> issue a preservation notice directing<br />

them to surrender media that may contain relevant e-mails. In the dispute at h<strong>and</strong>, the defendants<br />

sought reconsideration, arguing all relevant e-mail was preserved on backup tapes. Finding the<br />

defendants’ argument to be “fundamentally flawed,” the Magistrate Judge denied the motion for<br />

reconsideration, pointing out that e-mail present in a personal folder on an employee’s work station<br />

is not necessarily on the backup tape. However, as the defendants failed to keep track of which<br />

hard drives were used by which individuals, the Magistrate determined that the burdens imposed<br />

on the defendants to preserve all 545 workstations was too great, <strong>and</strong> therefore recommended no<br />

further relief beyond his previous recommendation.<br />

� Peskoff v. Faber, 2008 WL 2649506 (D.D.C. July 7, 2008). In this ongoing contract dispute, the<br />

court followed up on its previous holding that it was appropriate to ascertain the cost of a forensic<br />

examination to determine if the cost was justified. After the previous ruling, both parties submitted a<br />

joint bid resulting in a vendor proposal of $33,000. Determining the forensic examination to be<br />

justified, the court considered whether the burden or expense justified a shift of cost to the<br />

requesting party. Finding the defendant’s inadequate search efforts, failure to preserve<br />

electronically stored information <strong>and</strong> overall unwillingness to take “discovery obligations seriously”<br />

caused the need for a forensic examination, the court refused to shift costs since the problem was<br />

one of the defendant’s “own making.”<br />

� Pederson v. Preston, 2008 WL 2358589 (D.D.C. June 11, 2008). In this employment<br />

discrimination litigation, the plaintiff filed a motion to compel discovery arguing that the defendant’s<br />

responses to a number of interrogatories were insufficient <strong>and</strong> the defendant improperly asserted<br />

attorney-client privilege. The defendant objected arguing that the plaintiff’s production requests<br />

were vague, overly broad, unduly burdensome <strong>and</strong> not reasonably calculated to lead to the<br />

discovery of admissible evidence. The defendant also defended its assertion of attorney-client <strong>and</strong><br />

work-product privilege by noting that the plaintiff had not specifically objected to any claim of<br />

privilege provided in the defendant’s privilege log. After analyzing each disputed interrogatory for<br />

relevancy <strong>and</strong> undue burden, the court granted the motion in part <strong>and</strong> denied in part. The court<br />

9

also agreed with the defendant’s privilege argument, holding that the defendant’s attorney-client<br />

privilege assertion would be sustained absent evidence that it was made in bad faith.<br />

� Alex<strong>and</strong>er v. F.B.I., 2008 WL 903115 (D.D.C. April 3, 2008). In this Privacy Act litigation, former<br />

employees <strong>and</strong> political appointees from the Reagan <strong>and</strong> Bush administrations brought suit against<br />

the FBI alleging violation of privacy interests after their FBI files were improperly h<strong>and</strong>ed to the<br />

Clinton White House – a sc<strong>and</strong>al known as “Filegate.” The plaintiffs filed an emergency motion to<br />

supplement their motion to compel <strong>and</strong> request for evidentiary hearing, claiming the Executive<br />

Office of the President (“EOP”) filed a false declaration in an attempt to obstruct the narrowed<br />

request for e-mail. Finding the plaintiffs did not demonstrate the EOP obstructed the e-mail<br />

request, or acted in bad faith, the court concluded no credible evidence existed to grant the<br />

emergency motion. In making this determination, the court found the essential errors committed by<br />

the White House’s counsel were a result of the lawyers’ lack of familiarity with computer<br />

terminology, all of which occurred long before the “current sophisticated ways that lawyers have<br />

had to learn to deal with computer experts.”<br />

� Equity Analytics, LLC v. Lundin, 2008 WL 615528 (D.D.C. Mar. 7, 2008). In this suit, the plaintiff<br />

claimed the defendant, a former employee, illegally accessed electronically stored information after<br />

being terminated. The parties agreed a computer forensics examination was necessary to analyze<br />

the defendant’s computer, but could not reach agreement on how the examination should<br />

progress. To protect his privacy, the defendant sought to restrict the search by keywords <strong>and</strong> file<br />

type, but the plaintiff argued such would be under inclusive. Recognizing that the effectiveness of a<br />

particular search methodology requires expert testimony, Magistrate Judge Facciola required the<br />

plaintiff to submit an affidavit from its examiner explaining, inter alia, the limitation of the proposed<br />

search, how the search is to be conducted, whether a mirror image would be a perfect copy <strong>and</strong><br />

whether there would be some reason to preserve the drive once imaged.<br />

� Tequila Centinela, S.A. de C.V. v. Bacardi & Co. Limited, 2008 WL 565100 (D.D.C. March 4,<br />

2008). In this trademark registration dispute, the defendant sought attorney’s fees <strong>and</strong> costs<br />

associated with the plaintiff’s failure to comply with an earlier discovery order. The defendant<br />

sought monetary reimbursement for the filing of the second motion to compel as well as the<br />

pending motion for fees <strong>and</strong> costs. The plaintiff argued the time spent on unrelated issues <strong>and</strong><br />

those the defendant did not ultimately prevail on should not be awarded. Additionally, the plaintiff<br />

claimed that the defendant’s time estimation was grossly unreasonable <strong>and</strong> excessive. Agreeing<br />

with the plaintiff, the court denied reimbursement for ordinary litigation activities, including time<br />

spent on document review <strong>and</strong> related activities <strong>and</strong> internal discussions concerning the plaintiff’s<br />

discovery failures.<br />

� United States v. O’Keefe, 2008 WL 449729 (D.D.C. Feb. 18, 2008). In this suit, the government<br />

alleged the defendant received gifts from the co-defendant in exchange for expedited visa<br />

requests. The defendants filed a motion to compel claiming the government did not fulfill the<br />

responsibilities set forth in a previous discovery Order. Included within the electronic search were<br />

electronic documents <strong>and</strong> e-mails that the defendants claimed were produced in a manner<br />

rendering them unidentifiable. Applying Fed.R.Civ.Pro. 34, the court ordered the parties to<br />

participate in a good faith attempt to reach an agreement on production in a readily usable format.<br />

� D’Onofrio v. SFX Sports Group, Inc., 2008 WL 189842 (D.D.C. Jan. 23, 2008). In this<br />

employment discrimination case, the plaintiff brought suit against her former employer alleging<br />

disparate treatment based on gender, a hostile work environment <strong>and</strong> termination in retaliation for<br />

protected activities. After several discovery conferences <strong>and</strong> motions, the case was referred to<br />

Magistrate Judge John M. Facciola for management of the discovery process. In the current motion<br />

10

to compel, the plaintiff sought production of a document known as the “Business Plan” in its original<br />

electronic format with accompanying metadata <strong>and</strong> claimed the defendant caused deliberate<br />

spoliation of electronic records <strong>and</strong> failed to produce relevant documents. The defendant argued<br />

production of the Business Plan in its original format was not required by FRCP 34 absent a<br />

specific request <strong>and</strong> it never received any correspondence alleging deficiencies in its production.<br />

The judge determined that because the plaintiff failed to request the Business Plan in a specific<br />

format, she was precluded from seeking reproduction in a different format because the “if<br />

necessary” clause of FRCP 34 establishes the permissible scope of a discovery request but does<br />

not establish constraints on the manner of production. Additionally, the judge ordered an<br />

evidentiary hearing to assess the merits of the spoliation claim, finding the record simply too thin.<br />

� Hubbard v. Potter, 2008 WL 43867 (D.D.C. Jan. 3, 2008). In this suit, the plaintiffs claimed they<br />

were denied an interpreter at safety meetings, preventing them from safely <strong>and</strong> properly performing<br />

their duties. The defendant filed a motion to end pre-certification discovery, arguing the plaintiff had<br />

adequate time to complete discovery. The plaintiffs argued that the defendant’s production was<br />

insufficient <strong>and</strong> incomplete. The court granted the defendant’s motion <strong>and</strong> found that the plaintiffs<br />

failed to show that documents produced by the defendant permitted a reasonable deduction that<br />

other documents existed <strong>and</strong> refused to rely on the plaintiffs’ mere “hunch” or “speculation”. The<br />

plaintiffs also claimed additional discovery was warranted due to the defendant’s labeling of<br />

responsive documents as non-responsive <strong>and</strong> failing to initially produce them. Based on this<br />

argument, the court ordered an evidentiary hearing to determine whether additional production may<br />

be warranted.<br />

� Smith v. Café Asia, 2007 WL 2849579 (D.D.C. Oct. 2, 2007). In this suit alleging sexual<br />

discrimination, assault <strong>and</strong> battery, the defendant, a former employer of the plaintiff, sought images<br />

stored on the plaintiff’s cell phone to prove the plaintiff invited the treatment that incited the suit.<br />

The case was referred to United States Magistrate Judge Facciola for resolution. Judge Facciola<br />

stated that Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 is not an “all-or-nothing proposition” <strong>and</strong> the probative value of the<br />

sought-after materials must outweigh their prejudice. After conducting a Rule 26 <strong>and</strong> Federal Rule<br />

of Evidence 412 analysis, Judge Facciola ordered the plaintiff to preserve the stored images.<br />

Additionally, Judge Facciola allowed the defendant to designate one attorney to inspect the stored<br />

images in order to provide the trial judge with a fully informed debate regarding the images’<br />

admissibility.<br />

� United States v. Ferguson, 508 F.Supp.2d 7 (D.D.C. Sept. 10, 2007). In this drug trafficking<br />

prosecution, the defendant moved to suppress Yahoo! <strong>and</strong> MSN Hotmail e-mail evidence obtained<br />

by the government, which was seized pursuant to the magistrate judge’s order under the Stored<br />

Communications Act (SCA). The defendant challenged the SCA’s constitutionality, <strong>and</strong> in turn, the<br />

government argued that the constitutionality of the SCA had no bearing on whether the evidence<br />

warranted suppression. Denying the defendant’s motion to suppress, the court found that the SCA<br />

does not provide a suppression remedy <strong>and</strong> concluded that the government’s reliance on the SCA<br />

was objectively reasonable.<br />

� Peskoff v. Faber, 2007 WL 2416119 (D.D.C. August 27, 2007). In this ongoing discovery battle,<br />

unsatisfied with the defendant’s compliance with discovery obligations, the court ordered the<br />

defendant to search all depositories of electronic information in which one could reasonably expect<br />

to find emails where plaintiff’s name appeared. The plaintiff claimed there was no email from mid-<br />

2001 to mid-2003 in the defendant’s original production with the plaintiff as recipient or sender or<br />

any with his name in the text. However the plaintiff maintained the same email account from June<br />

of 2000 to April 2004. The court ordered an evidentiary hearing at which the defendant failed to<br />

11

appear, so the court construed his failure to comply with the order against him <strong>and</strong> proceed to<br />

other evidence. The defendant’s counsel merely insisted any information not already produced was<br />

no longer in existence, so the court ordered the parties to seek estimates from experts for a search<br />

<strong>and</strong> production in tiff or pdf format to determine the importance of the discovery to the issue in the<br />

litigation.<br />

� Disability Rights Council of Greater Wash. v. Wash. Metro. Transit Auth., 2007 WL 1585452<br />

(D.D.C. June 1, 2007). In a suit alleging violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act, inter alia,<br />

the plaintiff motioned the court to order the defendant to restore <strong>and</strong> search backup tapes for<br />

discoverable information. The plaintiff claimed discovery of the backup tapes was necessary<br />

because the defendant’s e-mail system was programmed to automatically delete all e-mails after<br />

60 days, <strong>and</strong> the defendant did nothing to stop the obliteration since the filing of the law suit, over<br />

three years earlier. The defendant argued that such an order would create undue burden <strong>and</strong><br />

expense, <strong>and</strong> that there was little reason to suppose that the backup tapes would produce relevant<br />

information. The court granted the plaintiff’s motion noting that while, “[T]he newly amended<br />

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure initially relieve a party from producing electronically stored<br />

information that is not reasonably accessible because of undue burden <strong>and</strong> cost, I am anything but<br />

certain that I should permit a party who has failed to preserve accessible information without cause<br />

to then complain about the inaccessibility of the only electronically stored information that remains.”<br />

The court also ordered the parties to meet <strong>and</strong> confer to reach an agreement as to how the backup<br />

tape restoration, search, review, <strong>and</strong> production would be conducted. The court suggested concept<br />

searching as opposed to keyword searching as a more efficient search method, likely to produce<br />

more comprehensive results.<br />

� Peskoff v. Faber, 240 F.R.D. 26 (D.D.C. Feb. 21, 2007). In a suit alleging fraud, breach of<br />

fiduciary duty, breach of contract, <strong>and</strong> conversion inter alia, the plaintiff moved the court to compel<br />

the discovery of e-mails relating to the suit. In a previous electronic document production, there<br />

were unexplained time gaps which, the plaintiff argued, suggested a complete <strong>and</strong> accurate search<br />

was not completed by the defendant. The defendant argued that he would be willing to submit his<br />

hard drive for imaging by the plaintiff, but that he would not endure the costs of production. After<br />

supplemental submissions by the parties regarding the extent of the search, the court determined<br />

the defendant only searched two of the five places where e-mail evidence may be found <strong>and</strong> that<br />

this was not a sufficient search for relevant ESI. The court also ruled that the defendant must<br />

endure the costs of producing relevant ESI contained his hard drive, citing the new Federal Rules<br />

of Civil Procedure. The court stated that accessible data must be produced at the cost of the<br />

producing party <strong>and</strong> that “cost-shifting does not even become a possibility unless there is first a<br />

showing of inaccessibility.” It cannot be argued, stated the court, that “a party should ever be<br />

relieved of its obligation to produce accessible data merely because it may take time <strong>and</strong> effort to<br />

find what is necessary.”<br />

� Peskoff v. Faber, 2006 WL 1933483 (D.D.C. July 11, 2006). The court considered the plaintiff’s<br />

motion to compel the defendant to produce additional e-mails written by or addressed to the<br />

plaintiff while employed by the defendant. During discovery, the defendant presented the plaintiff<br />

with computer disks that the defendant asserted contained “all [plaintiff’s] electronic files, including<br />

documents stored on his computer hard drive, e-mail, <strong>and</strong> any other [plaintiff] electronic<br />

documents.” However, the discovery production did not include two years worth of e-mails received<br />

or authored by the plaintiff from 2001 through 2003. The plaintiff argued the defendant failed to<br />

adequately explain the missing e-mails or detail the steps taken to search for the e-mails in the<br />

defendant’s computer system or archives. Countering, the defendant maintained no documents<br />

12

had been withheld, <strong>and</strong> if e-mails were missing, they no longer existed. The defendant informed<br />

the court that it subleases space from a law firm <strong>and</strong> its electronic files were stored on the law<br />

firm’s server. The court observed there were several possible locations where the missing e-mails<br />

could be located, including the plaintiff’s e-mail account at work, other employee accounts, on hard<br />

drives of company computers <strong>and</strong> on backup tapes of the law firm’s server. The court ordered the<br />

defendant to provide a detailed affidavit specifying the nature of the search the defendant<br />

conducted in locating the responsive e-mails. It further ruled the plaintiff would then have ten days<br />

to respond to the adequacy of the search described in the affidavit <strong>and</strong> at that point the court would<br />

consider whether additional searches were necessary.<br />

� J.C. Associates v. Fidelity & Guar. Ins. Co., 2006 WL 1445173 (D.D.C. May 25, 2006). In an<br />

insurance coverage dispute, the plaintiff challenged the defendant’s interpretation of a policy<br />

exclusion clause <strong>and</strong> sought discovery of related claim <strong>and</strong> litigation files in the defendant’s<br />

possession. The defendant resisted the discovery request, but conducted a preliminary electronic<br />

search of its 1.4 million claim <strong>and</strong> litigation files <strong>and</strong> identified 454 related claims. The judge<br />

articulated that the issue of whether or not to order discovery of the defendant’s files was not a<br />

matter of “relevance, but rather burdensomeness.” The judge ordered file-sampling, instructing the<br />

defendant to r<strong>and</strong>omly select <strong>and</strong> scan 25 of the 454 identified claims into an electronically<br />

searchable document. The court identified four specific search terms that the defendant should use<br />

in conducting <strong>and</strong> electronic search of the claims for responsiveness. The judge instructed the<br />

defendants to review documents containing those keywords <strong>and</strong> to produce any non-privileged,<br />

responsive information to the plaintiff. The court retained the authority to dem<strong>and</strong> further discovery<br />

<strong>and</strong> allocate costs after reviewing the information produced from the 25 files.<br />

� Breezevale Ltd. v. Dickinson, 879 A.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 2005). A tire distributing company brought<br />

an action against its attorneys for legal malpractice. The company alleged the attorneys should<br />

have delayed the deposition of one of the company’s employees until the company could further<br />

investigate the employee’s conduct. The employee being deposed claimed she forged documents<br />

relating to a lawsuit against a tire manufacturing company at the direction of <strong>and</strong> in collaboration<br />

with company executives. At trial, the court dismissed the legal malpractice lawsuit <strong>and</strong> imposed<br />

fees upon the company for knowingly bringing a suit based on forged documents. A computer<br />

evidence expert testified two documents were created on the employee’s computer with a last<br />

access date that corroborated the employee’s testimony. In addition, the expert determined one of<br />

the documents was computer-generated, even though the defendant did not own a computer at<br />

that time. Other evidence of forgery included two documents that were typed on a letterhead that<br />

did not exist at the time of the alleged document create dates. Based on this evidence, the trial<br />

court came to the “inescapable conclusion” the documents at issue were forged. The appellate<br />

court affirmed the lawsuit dismissal <strong>and</strong> award of $4 million in fees based on its finding that<br />

sufficient evidence demonstrated the company’s executives knew <strong>and</strong> participated in the forgeries.<br />

However, the court vacated the $1 million punitive sanctions, noting, “[t]he other sanctions imposed<br />

by the trial court themselves bore ‘punitive’ elements.”<br />

� Wild v. Alster, 377 F.Supp.2d 186 (D.D.C. 2005). In a medical malpractice lawsuit, the plaintiff<br />

moved for a new trial after the jury found in favor of the defendant. The plaintiff alleged the court<br />

erroneously denied a request for an expert examination of the defendant’s computer. In particular,<br />

the plaintiff sought to discover if certain dates, specifically the date photographs of her face were<br />

taken, could be retrieved from the defendant’s hard drive. The original photographs were lost<br />

during a computer system conversion; however, the defendant was able to recover some of the<br />

photos with the assistance of a data recovery service. The recovered photos only displayed the<br />

13

dates on which the photos were imported into the new system <strong>and</strong> not the dates on which they<br />

were originally taken. Despite this, the plaintiff asserted the defendant’s computer consultant<br />

testified in a deposition that the original dates were retrievable. In reviewing the deposition<br />

testimony, the court determined the expert actually stated it would be impossible to print any of the<br />

photographs with dates indicating when they were originally taken. In denying the motion for a new<br />

trial, the court concluded the plaintiff was not prejudiced by being prohibited from presenting the<br />

import date information to the jury <strong>and</strong> further stated that the court was well within its bounds to<br />

prevent further discovery of the computer system given the plaintiff’s request was made a year <strong>and</strong><br />

a half after the discovery period closed.<br />

� Jinks-Umstead v. Engl<strong>and</strong>, 227 F.R.D. 143 (D.D.C. 2005). In a case involving discrimination<br />

allegations against the U.S. Navy, the court granted a new trial to allow the plaintiff to present its<br />

case using new evidence which the defendant initially claimed it no longer had <strong>and</strong> did not produce<br />

during discovery. At trial, after the defendant produced this information – 1,400 pages of reports<br />

generated from a database – for the first time, the court granted the plaintiff’s motion for a new trial<br />

<strong>and</strong> for additional limited discovery. After the court granted the motion, the plaintiff filed a series of<br />

related post-trial discovery motions. The plaintiff requested, inter alia, compliance with an earlier<br />

order to provide access to the defendant’s database for review by either the plaintiff’s counsel or a<br />

computer technology consultant, to determine if information could be retrieved from the database.<br />

The defendant argued it had given the plaintiff access to the database during a specified time, but<br />

the plaintiff failed to accept the offer. The court declined to analyze whether the plaintiff forfeited its<br />

database inspection opportunity because new deposition testimony of one of the defendant’s<br />

employee’s indicated the information could be retrieved by specific data queries. Based on this<br />

testimony, the court ordered the defendant to query the database, retrieve the relevant information,<br />

<strong>and</strong> produce it to the plaintiff within 60 days of the order. See also Jinks-Umstead v. Engl<strong>and</strong>, 2005<br />

WL 3312947 (D.D.C. Dec. 07, 2005)(Distinguishing Morgan Stanley decision in concluding adverse<br />

inference instruction not appropriate where defendant did not act with “evil intent, bad faith, or<br />

willfulness.”).<br />

� Judicial Watch, Inc. v. United States Dep’t. of Justice, 337 F.Supp.2d 183 (D.D.C. 2004), rev’d,<br />

432 F.3d 366 (D.C. Cir. 2005). The defendants filed a motion for reconsideration of the court’s<br />

earlier ruling relating to the production of nine e-mail messages for which they had asserted the<br />

attorney work-product privilege. Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the court had<br />

previously required the defendants to provide the plaintiff with redacted copies of the privileged emails.<br />

In its motion for reconsideration, the defendants argued that the FOIA segregability<br />

requirement – m<strong>and</strong>ating production of “any reasonably segregable portion of a record” – did not<br />

apply <strong>and</strong>, as a result, the e-mails did not need to be produced. The court rejected this argument,<br />

holding that the FOIA segregability requirement applies to all documents, including e-mails.<br />

Emphasizing that the defendants made no effort to separate factual <strong>and</strong> privileged material, the<br />

court denied the defendants’ motion <strong>and</strong> ordered production of the redacted copies. On appeal, the<br />

court determined the entire contents of the e-mails were prepared in anticipation of litigation,<br />

protected by the attorney work-product doctrine, <strong>and</strong> exempt from disclosure.<br />

� United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 327 F.Supp.2d 21 (D.D.C. 2004). In a case brought by<br />

the government involving smoking <strong>and</strong> health related issues, the government filed a motion for<br />

evidentiary <strong>and</strong> monetary sanctions against the defendants for spoliation of evidence. Although the<br />

court had ordered preservation of all potentially relevant documents, the defendants continued to<br />

delete e-mail when it became sixty days old, on a monthly systemwide basis for a period of two<br />

years after the court order. Even after learning about their inadequate document retention policy,<br />

14

the defendants continued to destroy documents for several months, including relevant e-mails from<br />

at least eleven company supervisors <strong>and</strong> officers. In addition, the defendants failed to notify the<br />

court about the situation until four months after they found out about it. Finding that a significant<br />

number of e-mails had been permanently destroyed, the court declared that “it is astounding that<br />

employees at the highest corporate level in Philip Morris, with significant responsibilities pertaining<br />

to issues in this lawsuit, failed to follow [the] Order…which, if followed, would have ensured the<br />

preservation of those e-mails which have been irretrievably lost.” Granting the government’s motion<br />

for sanctions, the court stated that it will preclude the defendants from calling a key employee, who<br />

failed to follow the retention policy, as a fact or expert witness at trial. The court also ordered the<br />

defendants to pay costs relating to the spoliation as well as $2,750,000 in monetary sanctions. See<br />

also United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 223 F.R.D. 1 (D.D.C. 2004).<br />

� Arista Records, Inc. v. Sakfield Holding Co. S.L., 314 F.Supp.2d 27 (D.D.C. 2004). In a<br />

copyright infringement suit, the court issued an order compelling the defendant to produce<br />

computer servers, which hosted the defendant’s web site <strong>and</strong> contained records of its users. When<br />

the plaintiffs’ computer expert inspected the servers, he discovered that the vast majority of that<br />

information had been intentionally destroyed after the defendant learned that litigation was<br />

imminent. The expert found that the defendant ran a program, designed to erase electronically<br />

stored information, more than 50 times from a remote location in an attempt to delete all electronic<br />

data from the servers. In spite of the defendant’s attempts, the expert recovered a small amount of<br />

data to support the plaintiffs’ claims. Although the defendant attempted to attack the plaintiffs’<br />

methodologies for extrapolating the number of users <strong>and</strong> downloads, the court indicated that the<br />

defendant was “in a poor position to attack plaintiffs’ evidence,” noting that “[d]estruction of<br />

evidence raises the presumption that disclosure of the materials would be damaging.” The court<br />

decided not to issue sanctions but instead encouraged the plaintiffs to move for appropriate<br />

sanctions as the case progressed.<br />

� In re Lorazepam <strong>and</strong> Clorazepate Antitrust Litig. v. Mylan Lab., Inc., 300 F. Supp. 2d 43<br />

(D.D.C. 2004). In a class action antitrust lawsuit, the plaintiff sought to compel discovery of<br />

electronic documents. The defendant objected to the request arguing that the documents had<br />

already been produced. The plaintiff responded, claiming that the unindexed document “dump”<br />

produced on CD-ROM did not meet the defendant’s obligation to match documents with discovery<br />

requests as closely as possible. The court required the plaintiff to take the CD-ROM’s to a<br />

computer forensic or electronic discovery expert before the court would require the defendant to<br />

index the information. The e-evidence expert was to ascertain whether the electronic information<br />

could be read <strong>and</strong> searched by commercially available software or converted to a format in which it<br />

could be done.<br />

� Bethea v. Comcast, 218 F.R.D. 328 (D.D.C. 2003). Former employee sought to compel the<br />

defendant to allow her to inspect their computer systems to determine whether the defendant<br />

possessed any additional documents that had not yet been produced in discovery. The defendant<br />

argued that the plaintiff should not be allowed to inspect its computers because the defendant had<br />

already produced all unprivileged documents in response to the plaintiff’s discovery requests.<br />

Additionally, the defendant claimed that the plaintiff did not show that relevant material existed on<br />

the computer systems or that the defendant was unlawfully withholding documents. Ruling in favor<br />

of the defendant, the court noted that the plaintiff did not show that the documents she sought<br />

actually existed or that the defendant unlawfully failed to produce them. The court further declared<br />

that mere suspicion that another party failed to respond to document requests was not enough to<br />

justify court-ordered inspection of the defendant’s computer systems.<br />

15

� L<strong>and</strong>mark Legal Foundation v. Environmental Protection Agency, 272 F. Supp. 2d 70 (D.D.C.<br />

2003). Concerned that documents responsive to its Freedom of Information Act request would not<br />

survive the transition between governmental administrations, the plaintiff requested the court to<br />

enter a preliminary injunction prohibiting the EPA from destroying, removing, or tampering with<br />

potentially responsive documents. The court granted the motion <strong>and</strong> issued an injunction. Despite<br />

the court’s order, the hard drives of several EPA officials were reformatted, e-mail backup tapes<br />

were erased <strong>and</strong> reused, <strong>and</strong> individuals deleted received e-mails. The court found the EPA in<br />

contempt <strong>and</strong> concluded that the appropriate sanction was to impose sanctions in the form of the<br />

plaintiff’s attorney’s fees <strong>and</strong> costs incurred as a result of the EPA’s conduct.<br />

� McPeek v. Ashcroft, 212 F.R.D. 33 (D.D.C. 2003). In its August 1, 2001 Order, the court ordered<br />

the defendant to search certain backup tapes to assist in ascertaining whether additional searches<br />

were justified. After completing this backup tape sample, the parties could not agree whether the<br />

search results produced relevant information such that a second search was justified. The<br />

magistrate stated, “[t]he frustration of electronic discovery as it relates to backup tapes is that<br />

backup tapes collect information indiscriminately, regardless of topic. One, therefore, cannot<br />

reasonably predict that information is likely to be on a particular tape. This is unlike the more<br />

traditional type of discovery in which one can predict that certain information would be in a<br />

particular folder because the folders in a particular file drawer are arranged alphabetically by<br />

subject matter or by author.” After examining the likelihood of relevant data being contained on<br />

each of the backup tapes, the magistrate ordered additional searches of selected backup tapes<br />

likely to contain relevant evidence.<br />

� United States v. First Data, 287 F. Supp.2d 69 (D.D.C. Oct. 31, 2003). In directing a Scheduling<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Case</strong> Management Order, the court ordered limits on paper <strong>and</strong> electronic document<br />

discovery. Specifically, the court instructed the parties to “produce documents in either hard copy<br />

form, or, in the case of electronic documents, in the native electronic format (or a mutually<br />

agreeable format).”<br />

� New York v. Microsoft Corp., 2002 WL 649951 (D.D.C. Apr. 12, 2002). Microsoft challenged<br />

several e-mails appended to the written testimony of one of the plaintiff’s witnesses, claiming that<br />

the statement contained therein were inadmissible hearsay. The court excluded multiple e-mail<br />

messages using the following reasoning: (1) they were offered for the truth of the matters they<br />

asserted, (2) had not been shown to be business records as required under Rule 803(6), <strong>and</strong> (3)<br />

contained multiple levels of hearsay for which no exception had been established.<br />

� Cobell v. Norton, 206 F.R.D. 324 (D.D.C. 2002). The court issued sanctions, including attorneys<br />

fees <strong>and</strong> expenses, under Rule 37 based upon the defendants’ request for a protective order<br />

clarifying that it “may produce e-mail in response to discovery requests by producing from paper<br />

records of e-mail messages rather than from backup tapes <strong>and</strong> may overwrite backup tapes.” The<br />

defendants had previously been ordered to produce the e-mail messages from the back-up tapes.<br />

The court held that the defendants’ motion for protective order clarifying their duty to produce the email<br />