Malmö Art Academy Yearbook 2009–2010

Malmö Art Academy Yearbook 2009–2010

Malmö Art Academy Yearbook 2009–2010

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Malmö</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Academy</strong><br />

<strong>Yearbook</strong> <strong>2009–2010</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong> <strong>2009–2010</strong> Yearb0ok<br />

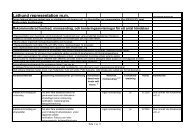

Table of Contents Foreword MFA2<br />

Elin Behrens<br />

Andreas Nilsson<br />

Per Kristian Nygård<br />

Hans Scherer<br />

Julian Stalbohm<br />

Agneta Strindinger<br />

Dea Svensson<br />

Ella Tillema<br />

Thale Vangen<br />

Fredrik Værslev<br />

Sara Wallgren<br />

MFA1<br />

Emil Ekberg<br />

Celie Eklund<br />

Karen Gimle<br />

Sarah Jane Gorlitz<br />

Jorun Jonasson<br />

Ingrid Koslung<br />

Ove Kvavik<br />

Juha Laakkonen<br />

Eric Length<br />

António Martins Leal<br />

Olof Nimar<br />

Pauliina Pietilä<br />

Titas Silovas<br />

John Skoog (exchange student)<br />

Asgeir Skotnes<br />

Susanne Svantesson<br />

Gunnhild Torgersen<br />

Lars Andreas Tovey Kristiansen<br />

Örn Alexander Ámundason<br />

2 3<br />

BFA3<br />

Søren Aagaard Jensen<br />

Majd Abdel Hamid<br />

Zardasht Faraj<br />

Malin Franzén<br />

Tim Hansen<br />

Nina Jensen<br />

Tomas Lundgren<br />

Stine Midtsæter<br />

Isis Mühleisen<br />

Max Ockborn<br />

Niklas Persson<br />

Danilo Stankovic´<br />

Maiken Stene<br />

Johanna Stillman<br />

BFA2<br />

Daniel Peder Askeland<br />

Martin Berring<br />

Matilde K Böcher<br />

Nathalie Fuica Sánchez<br />

Tiril Hasselknippe<br />

Susanne Johansson<br />

Stine Kvam<br />

Henning Lundkvist<br />

David Nilson<br />

Maria Norrman<br />

Eva Roel<br />

Jessica Sanderheim<br />

Julia Stepp<br />

Stine Wexelsen Goksøyr<br />

BFA1<br />

Ellinor Aurora Aasgaard<br />

Jóhan Martin Christiansen<br />

Marten Damgaard<br />

Cathrine Hellberg<br />

Elsine Hoff Levinsen<br />

Arvid Hägg<br />

Helena Olsson<br />

Michael Rold<br />

Emil Rønn Andersen<br />

Ihra Lill Scharning<br />

Jesper Weileby<br />

Madeleine Åstrand<br />

PhD<br />

Julie Ault<br />

Matthew Buckingham<br />

Mats Eriksson<br />

Frans Jacobi<br />

Simon Sheikh<br />

Apolonija Šušteršič<br />

Courses

This yearbook, like all yearbooks from the <strong>Malmö</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Academy</strong>, contains visuals and texts by students at the<br />

BFA and MFA levels, as well as by the six participants<br />

in the doctoral research programme. The <strong>Malmö</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> is proud to be part of Lund University,<br />

Scandinavia’s largest, and the yearbook is one<br />

important tool for fulfilling our commitment to what<br />

is usually called the ‘third mission’ of the universities:<br />

actively staying in contact with the society that embeds<br />

and nurtures us. Our first two missions are of course<br />

education and research. Other important tools for<br />

making the <strong>Academy</strong> accessible to the general public<br />

is our gallery, KHM, in which all graduating students<br />

exhibit their work, and our Annual Exhibition in the<br />

middle of May, when the entire <strong>Academy</strong> is turned<br />

into a public art gallery. It is only natural that many<br />

of the images in this book document installations at<br />

KHM from December 2009 to May 2010, and from the<br />

Annual Exhibition in May 2010.<br />

This year, like all years at the <strong>Academy</strong>, offered good<br />

examples of both continuity and change. The so-called<br />

Bologna System, the new two-tier organisation of higher<br />

education throughout Europe that also includes the<br />

fine art academies, has been in place at the <strong>Malmö</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Academy</strong> for a couple of years already. Yet in April 2010<br />

the KHM gallery hosted our first-ever group exhibition<br />

of an entire class of third-year students in the BFA<br />

programme. I wish to thank our two Senior Lecturers<br />

Maria Hedlund and P O Persson for their supervision<br />

of the graduating students and for organising their<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong> <strong>2009–2010</strong> Yearb0ok<br />

Foreword<br />

attractive and thought-provoking group exhibition.<br />

This exhibition will become part of the <strong>Academy</strong>’s<br />

yearly events calendar, since all BFA students now<br />

graduate after three years and then re-apply to the MFA<br />

programme at our <strong>Academy</strong> or elsewhere.<br />

The most significant change at the <strong>Academy</strong> during<br />

this year is that we have recruited three extraordinary<br />

artists as new faculty members. In the autumn semester<br />

2009 Danish artist Joachim Koester and Korean artist<br />

Haegue Yang joined us as part-time Professors of<br />

Fine <strong>Art</strong>, and at the same time Swedish artist Viktor<br />

Kopp became our new Junior Lecturer in Fine <strong>Art</strong>.<br />

Another addition to the list of teachers affiliated with<br />

the <strong>Academy</strong> is Swedish artist Andreas Eriksson, who<br />

started working as Visiting External Tutor of Fine <strong>Art</strong>,<br />

also in the autumn. I am very pleased that we have<br />

managed to attract such experienced, dedicated and<br />

internationally visible artists to our <strong>Academy</strong>, and I<br />

wish them the best of luck in their new roles. Judging<br />

from this first year, their future as teachers looks bright<br />

indeed. I also wish to thank the four distinguished<br />

art professionals in the External Experts’ Panel who<br />

helped us recruit the two new professors: Lynne Cooke,<br />

Chief Curator and Deputy Director at the Museo<br />

Nacional Centro de <strong>Art</strong>e Reina Sofía in Madrid; Olav<br />

Christopher Jenssen, Professor at the University of <strong>Art</strong><br />

Braunschweig in Germany; Jan Kaila, Professor at the<br />

Finnish <strong>Academy</strong> of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s in Helsinki and Annica<br />

Karlsson Rixon, Doctoral Candidate in Fine <strong>Art</strong>s at<br />

Gothenburg University. My thanks also go to the staff<br />

at the <strong>Malmö</strong> Faculty of Fine and Performing <strong>Art</strong>s and<br />

to our Dean Dr Håkan Lundström for facilitating the<br />

complex selection process and supporting the <strong>Academy</strong><br />

in every possible way.<br />

This academic year also saw the inauguration, on<br />

19 May 2010, of Inter <strong>Art</strong>s Center in <strong>Malmö</strong>, a new<br />

state-of-the-art interdisciplinary facility set up and<br />

managed jointly by the Academies of <strong>Art</strong>, Music and<br />

Theatre, which all belong to the <strong>Malmö</strong> Faculty of Fine<br />

and Performing <strong>Art</strong>s at Lund University. IAC, which<br />

has been in the making for several years, will become<br />

a very significant resource for art practitioners in the<br />

region and internationally. Please visit www.iac.lu.se<br />

for updated information about the programming and<br />

various ways to use the facility.<br />

There have also been changes in the <strong>Academy</strong>’s<br />

administrative and technical staff during this academic<br />

year. Charlotta Österberg joined the team as our new<br />

Economist in August 2009. Sven Yngve Oscarsson,<br />

our Technical Manager, has been scaling down his<br />

engagement at the <strong>Academy</strong> during the year, and<br />

will eventually make the full transition to his new<br />

function as Site Manager of Inter <strong>Art</strong>s Center. Annika<br />

Michelsen, our Departmental Secretary, is leaving the<br />

<strong>Academy</strong> during the autumn semester 2010 to join<br />

the staff of our sister organisation, the <strong>Malmö</strong> Theatre<br />

<strong>Academy</strong>. I thank Sven Yngve and Annika for their<br />

professionalism and their long-standing dedication<br />

to the <strong>Academy</strong>, and I welcome Charlotta in her new<br />

position, in which she has shown herself to be a highly<br />

Anders Kreuger<br />

Editor of the <strong>Yearbook</strong>, Director<br />

of the <strong>Malmö</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Academy</strong><br />

until July 2010<br />

4 5<br />

qualified and much-appreciated colleague.<br />

I myself left my position as Director in July 2010,<br />

to continue pursuing my career as a curator of<br />

contemporary art at Lunds konsthall in Sweden and at<br />

M HKA, the museum of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> in Antwerp,<br />

Belgium. Professor Gertrud Sandqvist, my predecessor<br />

as Director, will now become <strong>Art</strong>istic Director of the<br />

<strong>Academy</strong>, and the Silvana Hed will become the new<br />

Administrative Director. I want to use this opportunity<br />

to thank all my colleagues at the <strong>Academy</strong> for the<br />

efficient and cordial collaboration that I have enjoyed<br />

during my three years in the job. It has been a privilege<br />

to work for the <strong>Malmö</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> – with the faculty,<br />

the staff, and not least our students, who are the main<br />

characters in everything we perform together as an<br />

<strong>Academy</strong>. I am confident that the <strong>Academy</strong>’s future will<br />

be bright, and that the future of those who graduate<br />

from it will be even brighter.<br />

The yearbook is meant to reflect the prime<br />

importance of our students and doctoral candidates.<br />

Their work, their development, their achievements are<br />

the <strong>Academy</strong>’s most important resource and its raison<br />

d’être. It is my hope that this book will show that the<br />

<strong>Academy</strong> has every reason to be proud of its students.<br />

I wish to thank them for their contributions to the<br />

yearbook, and at the same time I also wish to give<br />

credit to those who have helped me to edit and produce<br />

it, notably Fiona Key, our excellent English language<br />

editor, and Povilas Utovka, the gifted graphic designer<br />

who has now made his second yearbook for us.

<strong>2009–2010</strong> Yearb0ok<br />

MFA 2<br />

7

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

Properly prime your lips to ensure that your lip<br />

makeup will last longer. Apply your foundation<br />

or concealer over the lips and lip contours.<br />

Use a synthetic brush to meticulously reach<br />

smaller areas. Afterwards, fix your base with<br />

powder before you add colour from lip pencil<br />

and lipstick. 1<br />

Approaching the end of my formal education<br />

in fine art, I have come to wonder: when did it<br />

actually begin? Or rather, when did my training<br />

in painting begin? At kindergarten? In school?<br />

Or when, as a young teenager, I was studying the<br />

make-up tips of glossy women’s magazines? These<br />

magazines contained all possible knowledge about<br />

the art of make-up: how to lay a good foundation,<br />

which brushes to use and which color shades to<br />

buy. Perfect concealer, powder puff, cherry red…<br />

These were terms familiar to me long before I had<br />

ever heard about fine art painting supplies such<br />

as gesso foundation, squirrel brushes or cadmium<br />

red. Suppose this was where I acquired my basic<br />

knowledge in painting, then, what did I actually<br />

learn? I learned the craft, of course, I learned<br />

precision – but most of all, I learned the art of<br />

covering up. Covering up reality, creating a new one.<br />

As I moved on to fine art, this was what I brought<br />

with me. The make-up was replaced by oil paint, the<br />

face by canvas, but the act remained the same: I was<br />

covering up.<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

Elin Behrens<br />

All Made Up<br />

Today, imagining paint as make-up allows me<br />

to focus on this particular aspect of painting, that<br />

is, painting as a concealing activity. Covering a<br />

surface with paint corresponds to a profound human<br />

tendency to manipulate the viewer, to present an<br />

image to the world in the same manner as make-up<br />

can be used: as a mask. A mask behind which one<br />

is protected from the eyes of others – and free to<br />

be whoever one prefers. In the thinking of French<br />

psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, this is how the artist<br />

uses painting: as a screen to ward off the gaze of the<br />

spectator. He calls it dompte-regard, to ‘tame the<br />

gaze’. But what is this gaze?<br />

According to Lacanian theory, there is a split<br />

between the eye – that is, ourselves, looking at the<br />

objects of the world – and the gaze, which is the<br />

imaginary ‘eyes’ of the objects looking back at us. In<br />

other words, it is the tendency to see ourselves ‘from<br />

outside’. Inevitably, we also try to adapt to this gaze,<br />

which is not necessarily the gaze of a specific object<br />

or person, but what Lacan calls the objet (petit) a.<br />

This ‘little other’ is closely related to desire. Desire<br />

is always a desire for someone else to desire us: to<br />

be loved or recognised. As infants, this is what we<br />

demand from our mother. When faced with the fact<br />

that she cannot give us the undivided love we crave,<br />

we start to search for it elsewhere. This is the objet<br />

(petit) a: an object which we imagine could supply us<br />

with that which we lack. But this object can never be<br />

attained, primarily because it is not an object at all. It<br />

is merely a reflection of our own ego, our own lack.<br />

Nevertheless, we keep searching for it through all our<br />

lives: in lovers, art etc. In the field of the visible, the<br />

objet (petit) a is experienced as the gaze: a feeling of<br />

being seen. We can imagine this gaze as being friendly<br />

or as being hostile. All the same, we form ourselves in<br />

relation to it.<br />

Returning to painting: why, then, would the painter<br />

want to ward off this gaze? Could it be because it<br />

is experienced as an avid, demanding gaze full of<br />

hostility? If so, the natural response would be to<br />

try to pacify the gaze and to protect oneself from it.<br />

Protection may be accomplished through hiding – or,<br />

as in warfare, by the use of camouflage. Following<br />

Lacan, camouflage is linked to the phenomenon of<br />

mimicry in the animal kingdom. Mimetic activity<br />

is deployed in three major areas: travesty, in the<br />

charades of sexuality; intimidation, as showing one’s<br />

teeth to scare off enemies; and finally camouflage, to<br />

make oneself invisible. At the human level, mimicry<br />

is also manifested through painting, most obviously in<br />

the technique of trompe l’œil, to ‘fool the eye’. When<br />

painting an image so illusionistic that the beholder<br />

for a moment thinks it is real am I not, in fact,<br />

presenting the painting as something which it is<br />

not? Is it not a deceitful object, as the verb ‘to fool’<br />

implies? But as Lacan points out, this deception is<br />

also revealing something:<br />

What is it that attracts and satisfies us in<br />

trompe l’œil? When is it that it captures our<br />

attention and delights us? At the moment<br />

when, by a mere shift of our gaze, we are<br />

able to realize that the representation does<br />

not move with the gaze and that it is merely<br />

a trompe l’œil. For it appears at that moment<br />

as something other than it seemed, or rather<br />

it now seems to be that something else. The<br />

picture does not compete with appearance,<br />

it competes with what Plato designates for<br />

us beyond appearance as being the Idea. It<br />

is because the picture is the appearance that<br />

says it is that which gives the appearance that<br />

Plato attacks painting, as if it were an activity<br />

competing with his own. This other thing is the<br />

petit a, around which there revolves a combat<br />

of which trompe l’œil is the soul. 2<br />

In the Mirror<br />

In my work Mirror, Mirror I address these issues by<br />

the use of three-dimensional, illusionistic painting.<br />

A canvas cloth is mounted upon a stretcher – the<br />

traditional support of painting – but instead of<br />

creating a flat surface the canvas is folded like a<br />

curtain. Upon this surface, an illusionistic painting of<br />

a curtain is made. A bright light falls on it, as if lit up<br />

8 9<br />

by two invisible spotlights, or, as the illusion fades,<br />

made-up with a shimmering highlighter. At a closer<br />

look, even the pink painted cloth is reminiscent of<br />

greasy pancake make-up.<br />

On the opposite wall a two-dimensional painting<br />

is placed, representing the curtain, but reversed, as<br />

if seen in a mirror. The mirror is, of course, closely<br />

related to Lacan’s notion of the gaze. In front of<br />

the mirror – whether it is an actual mirror or the<br />

experienced gaze of the world around us – we form<br />

our identity. By the use of different masks – as in<br />

the very concrete example of make-up – we adjust<br />

ourselves to our surroundings.<br />

When putting on make-up, we simultaneously<br />

create a new appearance and hide another one. If we<br />

are successful, people believe our new ‘face’. If not,<br />

however, the make-up is experienced as concealment<br />

– as a mask – triggering the question of what may<br />

hide beneath the surface. What we do not see<br />

becomes the center of our attention, allowing us, as<br />

it does, to project our own fantasies upon it. This is a<br />

phenomenon commonly used in horror movies: the<br />

most horrifying scenes are not when the ‘monster’<br />

is shown but when it is not shown. Through small<br />

hints, we are led to create our own monster, rooted<br />

in our own fantasy, far more terrifying than anything<br />

else. In a similar manner, when faced with a painting,<br />

it is that which is not shown in the picture, that we<br />

actually experience. Maybe this is what Lacan refers<br />

to as the objet (petit) a: an inner truth triggered by,<br />

and projected onto, the outside world. In this sense,<br />

painting itself functions as a mirror, reflecting our<br />

desire as well as shaping it.<br />

The tendency to assume there is something<br />

behind, beneath or beyond the appearance, seems<br />

to be an important part of our culture, and maybe<br />

even of our nature. Perhaps this was also Plato’s<br />

experience when he separated Idea from appearance<br />

in his famous metaphor of the cave? Here, the<br />

appearances of the world – trees, horses, buildings<br />

etc – are but shadows of the true, superior world:<br />

the world of Ideas. Painting is also rejected as being<br />

mere appearance – a copy of reality – and as such<br />

unable to depict the truth. This is what Lacan is<br />

referring to in the passage quoted above. But Lacan<br />

seems to hold a different opinion: ‘the picture is<br />

the appearance that says it is that which gives<br />

the appearance.’ 3 In other words: painting is both<br />

appearance and Idea, simultaneously.<br />

When ascribing painting a higher value, as<br />

Lacan does here, appearance too becomes a subject<br />

of importance. In fact, what would a painting be<br />

without its appearance? Maybe similar to a human<br />

without identity – without a mask? When writing<br />

about the different roles we enact, in love and war,<br />

Lacan claims it is through our masks we meet life in<br />

the ‘most acute, most intense way’. 4 If this is so, is it<br />

not in the mask we have to look for the very essence<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

of a person? Contrary to what Plato says, this<br />

suggests a kind of truth in appearance itself.<br />

What the subject conceals and the way in<br />

which he conceals it, is also the very form of<br />

its exposure. 5<br />

Just like the mask can reveal the essence of a<br />

person, the ‘fake’ of trompe l’œil can reveal a hidden<br />

‘truth’, a truth which can only be expressed indirectly.<br />

If approached directly, it is lost. Only by concealment<br />

can it be found. Consequently, in my paintings, my<br />

aim is to show something – by hiding it. My challenge<br />

is to hide it in a proper way, giving the exact amount<br />

of information needed to let the observer’s mind<br />

interact with mine.<br />

I Am You<br />

When searching for a proper ‘hiding place’ for what<br />

I want to express, a motif to paint, I often choose<br />

everyday objects like parts of interiors, furniture,<br />

provisions. These objects seem discreet enough to<br />

shelter something else. In fact, this is also how I<br />

experience them: as something else. I can never<br />

quite accept that, for example, my bookshelf is only<br />

a bookshelf consisting of wood, glue, screws. It is<br />

always something more. For a long time, I thought this<br />

was just my own, silly imagination. Clearly, nothing<br />

was there except a bookshelf. But then I realised that<br />

quite a few thinkers had pondered this subject. One of<br />

them is of course Lacan with his theory about the gaze,<br />

claiming: ‘the spectacle of the world, in this sense,<br />

appears to us as all-seeing.’ 6 Above all, however, this<br />

is an area explored by the phenomenologists.<br />

Maurice Merleau-Ponty was a phenomenologist<br />

engaged in analysing how we, as subjects, experience<br />

the objects of the world. He argues that the borders<br />

between the subject and the object are not definite.<br />

The objects we surround ourselves with are, in fact, an<br />

extension of our bodies. An example of this is the blind<br />

man’s cane, which is not just an object for him, but an<br />

extended part of himself. It is important to Merleau-<br />

Ponty that the body is not simply a ‘shell’ for our<br />

conscience to inhabit, as in the body/mind dualism,<br />

but conscious in itself. Everything we experience,<br />

everything we think is founded in our bodies. This is<br />

how, when expanding our bodies to include objects<br />

around us, we also expand our consciousness, our<br />

subjectivity, and consequently, our vision:<br />

[…] vision happens among, or is caught in,<br />

things – in that place where something visible<br />

undertakes to see, becomes visible for itself by<br />

virtue of the sight of things; in that place where<br />

there persists, like the mother water in crystal,<br />

the undividedness of the sensing and the sensed. 7<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

Does this mean, when relating to my bookshelf as to<br />

another subject, I am actually relating to myself? That<br />

the bookshelf is me, and conversely, that I am the<br />

bookshelf? Mirroring each other, creating the notion<br />

of self? Moreover, is this not a basic function of<br />

empathy – to see oneself in others? A kind of empathy<br />

born from perception rather than thought, and<br />

therefore belonging to painting rather than language.<br />

The same phenomenon enabling me, when I look at a<br />

painting, to experience it as a physical sensation in my<br />

own body, and in that sense to become the painting.<br />

In-Between Dimensions<br />

The presence of the object, that is another reason why<br />

I am interested in the three-dimensionality of painting.<br />

Like the minimalists of the 1960s who transformed<br />

painting into object, I want the painting to be a<br />

physical presence in the gallery room, something to<br />

relate to with the body. But if the minimalists tried to<br />

achieve this by eliminating all traces of illusionism, I<br />

go in the opposite direction.<br />

For me, the imaginary world of classical painting<br />

has always been intriguing. In this world, seen<br />

through the ‘window’ of the painting, anything<br />

could happen. But still, this has never been quite<br />

enough. I have often experienced it like a fairytale,<br />

enacted somewhere else, in a two-dimensional<br />

universe. Instead, I have wanted it to happen here,<br />

I have wanted fantasy realised. This wish is strongly<br />

connected to my interest in the uncanny, a concept<br />

developed by Sigmund Freud. The uncanny is,<br />

according to him, when repressed memories suddenly<br />

reappear and are projected onto the outside world<br />

as a way of protecting ourselves from them. We<br />

then experience them as something real, external:<br />

something foreign yet strangely familiar. Our reaction<br />

is fear, as the uncanny threatens our identity and our<br />

worldview, but also fascination. It is this fascination<br />

that has guided me in my search for a visual language.<br />

If the uncanny exists in a kind of borderland – as an<br />

external materialisation of our inner mind – then how<br />

could I translate this into painting?<br />

With this in mind I have tried to bring together<br />

the three-dimensionality of minimalism, representing<br />

external reality for me, with the illusion of twodimensional<br />

painting, representing fantasy. By<br />

combining them I have endeavoured to make<br />

artworks both present, like objects in the room, and<br />

absent, belonging to that other world of painting. A<br />

kind of transitional objects: both real and illusory.<br />

Fantasy realised, but also reality fantasised.<br />

My first attempt at this was the work Through the<br />

Wall. The piece consists of eleven MDF boards shaped<br />

as wooden planks of different widths. Together they<br />

form a painting of a sauna wall seen in perspective,<br />

with a strong light coming from the right. This<br />

work could be seen in many different ways. On one<br />

hand as a traditional painting: a two-dimensional<br />

represention of a wall concerned with light and depth,<br />

a window showing us an imaginary world beyond the<br />

surface. On the other hand, we might see it as threedimensional<br />

objects, as real planks. In this case, there<br />

is no depth – no world beyond – but merely objects<br />

present in the gallery room. This oscillation between<br />

absence and presence seemed parallell to the border<br />

condition of the uncanny, and I imagined the wall as<br />

being transferred from a room inside a painting into<br />

the actual gallery space. An immaterial object.<br />

But there is also a third way of looking at this piece.<br />

If we do not notice the illusory depth of the painting,<br />

but do notice the illusory light, then we apprehend<br />

the piece as a real object, lit up by a light source that<br />

does not exist. Or rather: a light source that exists<br />

only in the world of painting. This world of painting<br />

seems, then, to be situated outside the painting itself,<br />

casting its light on the planks. As if it were floating<br />

around in the gallery space, invisible to the naked eye<br />

but possible to glimpse in the mirror of the painted<br />

planks. This is what the work becomes: a mirror, not<br />

a window, reflecting the invisible presence of what is<br />

often said to be dead: painting. Almost like a ghost.<br />

Through the Wall came to be as much concerned<br />

with the nature of painting as with the exploration<br />

of the uncanny. In fact, to me they even seem to<br />

be related. Think upon the way time functions in a<br />

painting. It is not a time which passes as in real life,<br />

nor a moment of time as in photography, but a time<br />

composed of several moments condensed into one.<br />

When a portrait is painted, the nose is painted one<br />

day and the cheek another day. Together they form<br />

a painting where all this time exist simultaneously. A<br />

parallel world, hanging on our living room wall, where<br />

the notion of time is more similar to eternity than to<br />

our ordinary chronology.<br />

The juxtaposition of painting and reality –<br />

whatever they are – has become a way for me to<br />

approach them both. In this sense, combining<br />

illusionism and minimalism is not just an act of<br />

joining opposites, but it also a way of making visible<br />

the character of painting itself as something both<br />

illusory and real, both absent and present, both<br />

immaterial and material, both depth and surface – all<br />

at once.<br />

The Word and the Image<br />

Maybe this is the reason why I hold on to painting:<br />

that it seems to unite all those things that language<br />

separates. Indeed, my interest in images has been<br />

developed as a kind of complement to language, as an<br />

investigation in what might be their unique, distinctive<br />

character. In comparison, it appears language is<br />

ascribed a higher significance in our culture. Not<br />

10 11<br />

least it is held to be the structure organising the self,<br />

enabling us to become subjects. Words construct us,<br />

they create meaning and provide us with a sense<br />

of control. But what about the image? Although I<br />

am constantly surrounded by images they remain a<br />

mystery to me. And as with all mysteries they are both<br />

frightening and fascinating. I cannot help trying to<br />

verbalise them. Still, they are always something else.<br />

They carry a meaning, but of a different kind. May this<br />

be the meaning experienced through intuition? In that<br />

case: What is intuition?<br />

Accumulated experience that is not immediately<br />

accessible to language, but which does affect<br />

our consciousness, is usually called intuition.<br />

An intuitive choice is thus as conscious as<br />

a considered choice, it simply uses aspects<br />

of consciousness that are not accessible to<br />

language. It cannot say, but it can show. 8<br />

It appears that intuition is a kind of non-verbal<br />

knowledge, a bank of experiences acquired through<br />

our bodies. Our senses connects us with memories<br />

in a way that language alone would fail to do. For<br />

example, a certain purple colour may bring back a<br />

memory of our mother’s nail polish. Such memories<br />

often have a strong emotional quality and a deep<br />

sense of meaning, and when we look at an image –<br />

or more specifically at a painting – they come into<br />

play. A painting may cause us to hallucinate a certain<br />

smell; it can make us strangely afraid or simply happy.<br />

The very lack of words to express or explain these<br />

experiences only seems to make them stronger, as if<br />

we could not protect ourselves from them. Maybe this<br />

is also why painting can be so demanding, as if this<br />

lack of verbal categorisation posed a threat to us.<br />

In this sense language seems to function as a kind<br />

of protection. When we name something we separate<br />

it from something else – and create a meaningful<br />

order. In this text, for example, I have separated<br />

object from painting, fantasy from reality and word<br />

from image, although I suspect, in fact, that they are<br />

closely intertwined. But this is how rational language<br />

functions: it separates. Poetic language, on the other<br />

hand, has another dimension: instead of separating,<br />

it seems to join together different meanings into<br />

one. This is how poetry has become, to me, far more<br />

related to painting than to rational language. And this<br />

is how poetry, as well as painting, can be so disturbing<br />

– and liberating. It shows reality in another, more<br />

complex, fashion.<br />

Another Kind of Meaning<br />

Why, then, do we need this protection? Why do we<br />

strive to separate, to create order? According to Julia<br />

Kristeva, another French psychoanalyst, our tendency<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

to separate is deeply rooted in our early childhood.<br />

As infants our ego is borderless, and we imagine<br />

ourselves as being one with our mother. But as<br />

development proceeds we lose this sense of symbiosis<br />

and start to develop as separate subjects. This is the<br />

first act of separation: to distance ourselves from our<br />

mother. In order to accomplish this we repress our<br />

longing for her, which turns into repulsion. In this<br />

way, we protect our fragile ego from being drawn back<br />

into the borderless condition – which, at this point,<br />

would mean psychosis. From now on, this is how we<br />

preserve our ego: by separation.<br />

In the same manner, as adults, we need to<br />

separate ourselves from certain things that pose<br />

a threat to our ego. These things are, in the<br />

terminology of Julia Kristeva, the abject. It may<br />

appear as a dead body, as excrement or as socially<br />

unacceptable behaviour, and we react to it with<br />

aversion, because it reminds us of what we are<br />

repressing in ourselves: death, dissolution, psychosis.<br />

These are all conditions in which the borders of our<br />

ego are annihilated, where we merge with the world<br />

around us. A part of life, for sure, but a part we need<br />

to repress in order to survive.<br />

But there is also another dimension to this. Just<br />

like the child is both repulsed and attracted to the<br />

mother, the abject provokes both repulsion and<br />

fascination in us. The feeling of being ‘one’ with the<br />

surrounding world is not just something we abhor,<br />

but also something we strive to attain – as, for<br />

example, in the mystic practices of different religions.<br />

The mystic experience of being ‘one with the world’<br />

is even interpreted, by some psychoanalysts, as a<br />

regression back to the mother–child symbiosis. It<br />

seems, apart from being the thing we fear deepest, the<br />

abject could also be what we desire most. Apart from<br />

dissolving meaning, it could also create meaning, but<br />

of a different kind.<br />

A Certain Kind of Glow<br />

The ambiguity of the abject leaves us with a<br />

challenge: to approach it without being lost in it.<br />

Maybe this is the challenge of the mystic? And<br />

maybe, this could also be the challenge of the artist?<br />

Kristeva suggests art can function as a purification of<br />

the abject, as catharsis:<br />

The various means of purifying the abject – the<br />

various catharses – make up the history of<br />

religions, and end up with that catharsis par<br />

excellence called art, both on the far and near<br />

side of religion. Seen from that standpoint,<br />

the artistic experience, which is rooted in<br />

the abject it utters and by the same token<br />

purifies, appears as the essential component of<br />

religiosity. 9<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

But how, then, could the abject be uttered? If<br />

we meet the abject directly, we are repulsed by it.<br />

If we analyse it rationally, we are protected from it.<br />

But maybe, through art, we are able to repeat it –<br />

to fictionalise it – and thereby experience it? As a<br />

kind of sublimation: a way of saying what cannot be<br />

said. Perception, words, may bring it about, but our<br />

experience is always something more. Once again, it<br />

seems as if we could never bear to meet this kind of<br />

reality directly – only indirectly:<br />

What is most irrational about the affective<br />

response to the near encounter of the uncanny,<br />

abject, Real is pointed to by Bryson when he<br />

suggests that the putative stimuli, the apparent<br />

object of horror underlying these affects is<br />

in fact ‘inadequate to the affective charge<br />

it carries with it: the horror is never in the<br />

representation, but around it, like a glow or<br />

a scent’. 10<br />

The horror is never in the representation, but<br />

around it, like a glow or a scent – just like the<br />

meaning of a painting is never in the representation,<br />

but glowing around it. Maybe this is the glow we<br />

apprehend through intuition – connecting us with<br />

hidden parts of ourselves? Maybe this is the glow we<br />

call the sublime?<br />

The Reality in Illusion<br />

We have reached the point when the different<br />

thoughts of this essay come together. To me, they are<br />

all related, they all revolve around the same core: a<br />

kind of present absence. Something residing behind<br />

the mask, inside the object, beyond rational language,<br />

and something which can only be experienced in this<br />

manner: behind, inside, beyond.<br />

The final work I would like to introduce concerns<br />

many of the subjects touched upon in this essay.<br />

Diptych, the title of the work, is to be read as literary.<br />

The work consists of two objects: a sofa and a painting<br />

placed above it. Hanging on the wall, the painting<br />

depicts a section of the sofa, and on the corresponding<br />

area of the sofa a painting has been made, resembling<br />

the painting on the wall. Looking at the piece from<br />

right in front, the painting on the sofa is perceived as<br />

having an identical shape and size as the painting on<br />

the wall. From another angle it is distorted, and we<br />

learn that this is an anamorphic image.<br />

This piece could be read as a comment on how<br />

painting is perceived. Is it just a decorative object<br />

made to match the living room sofa? Or could<br />

painting be something more, even a model for reality?<br />

Diptych provokes the question of what actually comes<br />

first: our fantasy about reality or reality itself. Does the<br />

painting resemble the sofa, or does the sofa resemble<br />

the painting? We are caught in an endless circular<br />

movement. This is, for me, the problem of dualism,<br />

the impossible choice it presents me with. I do not<br />

really want to choose either of the options, or maybe<br />

I would like to choose both. As Slavoj Žižek puts it,<br />

discussing the sequence in the film Matrix when the<br />

main character is presented with a choice between the<br />

blue pill of illusion and the red pill of reality:<br />

But the choice between the blue and the red<br />

pill is not really a choice between illusion and<br />

reality. Of course, the matrix is a machine for<br />

fictions, but these are fictions which already<br />

structure our reality. If you take away from our<br />

reality the symbolic fictions that regulate it, you<br />

lose reality itself. I want a third pill. So what<br />

is the third pill? Definitely not some kind of<br />

transcendental pill which enables a fake, fastfood<br />

religious experience, but a pill that would<br />

enable me to perceive not the reality behind the<br />

illusion, but the reality in illusion itself. 11<br />

And finally I am back where I started – in illusion.<br />

Not the platonic illusion, but an illusion of deep<br />

meaning, or even truth. It is, of course, a subjective<br />

truth, and as such the kind of truth artists are involved<br />

in. In fact, is this not exactly what artists are trying to<br />

do: telling lies so well they become true? Or better:<br />

giving the world a proper make-over, enabling us to<br />

meet it in its true appearance: all made up.<br />

12 13<br />

Notes<br />

1. Make Up Store Magazine. Stockholm: Make Up<br />

Store, Issue 13, no 1, 2010, p.36.<br />

2. Lacan, Jacques, The Four Fundamental<br />

Concepts of Psychoanalysis. New York/London:<br />

W W Norton & Company, 1998, p.112.<br />

3. Ibid.<br />

4. Ibid, p.107.<br />

5. Miller, Jacques-Alain, quoted by Renata Salecl<br />

in En liten bok om kärlek (‘A Small Book about<br />

Love’). Stockholm/Stehag: Brutus Östlings<br />

Bokförlag Symposion, 1997, p.19.<br />

6. Lacan, Jacques, op. cit., p.75.<br />

7. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, ‘Eye and Mind’, in<br />

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Basic Writings, edited<br />

by Thomas Baldwin. London/New York:<br />

Routledge 2004, p.295.<br />

8. Sandqvist, http://www.kaapeli.fi/-roos/<br />

gertrude.htm<br />

9. Schelling, Friedrich von, quoted by Freud in The<br />

Uncanny, New York: Penguin Books, 2003, p.132.<br />

10. Hook, Derek W, ‘Language and the Flesh:<br />

Psychoanalysis and the Limits of Discourse’, in<br />

Pretexts: Literary & Cultural Studies, Vol.12,<br />

Issue 1. Abingdon: Carfax Publishing Company,<br />

2003, p.61.<br />

11. Žižek, Slavoj/Fiennes, Sophie, A Pervert’s<br />

Guide to Cinema. DVD, P Guide Limited, 2006.<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

Bibliography<br />

Douglas, Mary, Renhet och fara (‘Purity and Danger’),<br />

translated by Arne Kallrén. Falun: Nya Doxa, 1997.<br />

Elkins, James, The Object Stares Back. San Diego/<br />

New York/London: Harcourt, 1996.<br />

Evans, Dylan, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian<br />

Psychoanalysis. London/New York: Routledge, 1996.<br />

Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny, translated by David<br />

McClintock. New York: Penguin Books, 2003.<br />

Hook, Derek W, ‘Language and the Flesh:<br />

Psychoanalysis and the Limits of Discourse’, in<br />

Pretexts: Literary & Cultural Studies, Vol.12, Issue 1.<br />

Abingdon: Carfax Publishing Company, 2003.<br />

Kristeva, Julia, Fasans makt (‘The Powers of Horror’),<br />

translated by Agneta Rehag and Anna Forssberg.<br />

Gothenburg: Daidalos, 1991.<br />

Lacan, Jacques, The Four Fundamental Concepts of<br />

Psychoanalysis. New York/London: W W Norton &<br />

Company, 1998.<br />

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, ‘Eye and Mind’, in Maurice<br />

Merleau-Ponty: Basic Writings, edited by Thomas<br />

Baldwin. London/New York: Routledge 2004.<br />

Salecl, Renata/Žižek, Slavoj, En liten bok om kärlek<br />

(‘A Small Book about Love’), translated by Maria<br />

Fittger and John Swedenmark. Stockholm/Stehag:<br />

Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposion, 1997.<br />

Sandqvist, Gertrud: On Intuition (http://www.kaapeli.<br />

fi/-roos/gertrude.htm).<br />

Sjöbom, Greta, ed., M Magazine. Stockholm: Make up<br />

Store AB: Issue 13, nr 01, 2010.<br />

Žižek, Slavoj/Fiennes, Sophie, A Pervert’s Guide to<br />

Cinema. London: DVD, P Guide Limited, 2006.<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

14 15<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

16 17<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

18 19<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

I strive to find my way in the world, in their world,<br />

through my own artistic vision. To find my place<br />

in the world, in society, among my friends and my<br />

family. Which is something I believe you do, and<br />

intend to do, when you find your ‘own’ space, and<br />

ignite a flame, a passion, and try to excel within that<br />

area. <strong>Art</strong>, in my case. I got involved in art by chance.<br />

Once I realised what you can accomplish with art,<br />

how it fits in with my ideas about life in general, then<br />

the passion came along as well. But this passion has<br />

a very limited scope. I very rarely read books about<br />

artists, and I never ever read about art history. For this<br />

reason, I don’t know much about different periods<br />

in art history. I can’t tell yet whether this helps or<br />

hinders me in my work. Of course, things sometimes<br />

get embarrassing and awkward when my creations<br />

reveal my ignorance of ‘obvious’ references. On the<br />

other hand, perhaps this provides me with a different<br />

perspective on my own art, which I would otherwise<br />

never have discovered. Either way, I’m incredibly<br />

passionate about my own work. Because I know I<br />

have found my place. I know that it is through my art<br />

that I will be able to find my own place in the world.<br />

I strive for recognition through my art. It is<br />

incredibly important to me for somebody to see and<br />

notice my art. I used to deny this, and try to convince<br />

myself that I made art for my own sake, for my own<br />

enjoyment. Not to get attention, whether positive or<br />

negative. To have what matters to you the most in<br />

life, the thing you put all your efforts into, be ignored<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

Andreas Nilsson<br />

I Strive<br />

would shatter and humiliate me. I want to show<br />

people what I do, even if I have to do it anonymously.<br />

Because I’m not an artist out of a desire for fame or<br />

fortune. But if nobody was to see, hear or feel what I<br />

create, or if it didn’t matter to me, then I could just as<br />

well limit my art to sketches, fragments and ideas in<br />

my mind.<br />

I strive to be generous in my art. For people to<br />

see, hear, and feel my art, and so on. I want the<br />

viewer to experience something. I understand that<br />

our brains are different, because of differences in our<br />

lives, environments and so on. For that reason, it’s<br />

impossible to give different people the exact same<br />

experience of a single work of art. But most of all, I<br />

want the experience or thoughts to continue to affect<br />

them – whether consciously or subconsciously – for<br />

the rest of their lives. A lasting impression.<br />

I strive to make my art personal to me. Sticking<br />

to the things I know and feel passionate about as<br />

subjects for my art. I don’t believe I can create good<br />

art about things that fail to fire me up and make<br />

me passionate. And just because I find something<br />

interesting, like war, politics, or a footballer’s<br />

biography, for instance, that doesn’t necessarily mean<br />

I’m passionate about it. (Naturally, I’m passionate<br />

about some things within those areas, as well.) I<br />

always try to find something in my pieces to give the<br />

viewers a sense of my personal attitude towards – or<br />

passionate feelings about – the subject or idea I am<br />

trying to illuminate.<br />

I strive for control. Control over the world I<br />

create. To know what the viewer’s experience will be.<br />

Even if the experience is to be just a small, confusing<br />

fragment that I ‘control’ by intentionally giving up<br />

control of my work.<br />

I strive to create feelings in my art that are<br />

otherwise unattainable to me. I’m usually a very stoic<br />

person. If something or somebody actually affects me<br />

in some way, I tend to brush it off right away. This<br />

goes for both happy and unhappy emotions. It doesn’t<br />

matter how wonderful or how awful I feel, I get it out<br />

of my head in a hurry anyway. No matter how big a<br />

deal it is, I consider it a trifle and toss it aside. And if<br />

it’s a problem that’s too big to get rid of right away,<br />

there’s always some way or other to detach myself<br />

from it, to forget about it for a while. And when the<br />

feelings related to this problem reappear later on,<br />

they have faded to some degree. If this procedure is<br />

repeated a sufficient number of times, the problem<br />

becomes so insignificant that I can easily forget or<br />

ignore it. But some feelings transform into something<br />

else instead, something I can’t feel unless I sit down<br />

and look for it. This is the kind of emotional change I<br />

want to effect through my art.<br />

I strive to be poetic. Fragility, beauty, roughness,<br />

ugliness. Anything can be poetic. It’s all about<br />

the unpredictable sensations that the viewer can<br />

experience. Keeping my expressions subtle. Even<br />

when I’m as straightforward as I can be.<br />

I strive to be basic. To keep elements that confuse<br />

the pieces to a minimum, without making them too<br />

obvious. I want to make art that is approachable<br />

and easy to relate to. And I want to do these things<br />

without telling anybody what to think. It makes for<br />

a difficult balance between talking down to your<br />

audience by making your expressions too obvious,<br />

and mistakenly assuming that the things you’ve spent<br />

months working hard on inside your mind are easily<br />

grasped by others. I start off with my own ideas, and<br />

try to be objective and imagine myself in the position<br />

of a viewer of my own art.<br />

I strive never to compromise in my art. Even<br />

though the viewer is extremely important to me<br />

in my role as an artist. Even though the viewer’s<br />

appreciation is extremely important. Despite the fact<br />

that I want the viewer to grasp my intention or idea, I<br />

won’t compromise to make it so. I’d rather scrap the<br />

whole idea and start over. Because the most important<br />

thing, after all, is that I need to be able to commit fully<br />

to every piece I show.<br />

My Creative Process<br />

I often use a downward spiral to find inspiration in<br />

life. This spiral consists of sloth, egoism and alcohol,<br />

and is contributive to degeneration. This is the state<br />

where I often find the starting points for my work,<br />

20 21<br />

and it also contributes to the time-consuming nature<br />

of my process. I do these things without romanticising<br />

decadence. I do it because I think that in difficult<br />

times, even difficult times you brought upon yourself<br />

on purpose, you can grow a lot from getting yourself<br />

out of the difficulties. When I come up with an idea<br />

that relates to a particular subject, I start dwelling on<br />

different ideas, going back and forth in my mind. I try<br />

to keep them in my thoughts for months. If the ideas<br />

still feel good enough after all that scrutiny, they are<br />

worth a try. Then it becomes a matter of finding the<br />

right medium, it doesn’t matter if it’s performance,<br />

sculpture, photography, or film. As long as it is the<br />

best fit for what I am trying to express.<br />

Music/Blues<br />

To me, music is without any doubt a great source<br />

of motivation and inspiration for art. For inspiration,<br />

I mostly listen to old blues singers like Lightnin’<br />

Hopkins and Howlin’ Wolf. They use simplicity,<br />

maybe just a harmonica or a guitar and some simple<br />

lyrics, along with repetition and emotion to create<br />

something incredibly moving and thought-provoking.<br />

The blues has been described as bad poetry made<br />

good by means of repetition. I don’t think it’s bad.<br />

But I do think that the blues, the way I like it, is<br />

often a very direct and simple kind of poetry. And the<br />

repeated phrases make it easier to get into the song.<br />

Which in turn makes it all feel more real, genuine<br />

and honest.<br />

Lightnin’ Hopkins: Trouble Blues<br />

Trouble, trouble, trouble.<br />

Trouble is all in the world I see.<br />

Trouble, trouble, trouble.<br />

Trouble is all in the world I see.<br />

Yeah you know I often wonder,<br />

What in the world gonna become of me.<br />

Now when I wake up in the mornin’,<br />

Blues and trouble all ‘round my bed,<br />

When I wake up in the mornin’,<br />

Blues and trouble all ‘round my bed,<br />

Yeah you know I never will forget.<br />

Last what I heard my baby said…<br />

What did she say, boy?<br />

She said: ‘Lightnin’, I’m leavin’ you in the mornin’,<br />

And your cryin’ won’t make me stay.’<br />

She said: ‘I’m leavin’ you in the mornin’,<br />

Lightnin’, your cryin’ won’t make me stay.’<br />

I just said: ‘I hope, little girl,<br />

Po’ Lightnin’ll meet you again some day.’<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

And she got sad, and I did too; we had to<br />

moan a little.<br />

Well, I had to tell’r: ‘If you just gotta go,<br />

Hope I’ll meet you again some day.<br />

If you just gotta go,<br />

Hope I’ll meet you again some day.<br />

Yes, when I do, little girl,<br />

You’ll be done, changed your evil way.’<br />

The blues is often about unrequited love, longing,<br />

death, money troubles, or other hard things in life. But<br />

there is just as often a more humorous side to things<br />

as well. Like in Howlin’ Wolf’s I Asked for Water.<br />

Here, he asks for water from a woman, who gives him<br />

gasoline instead. Which is very funny, at least to me.<br />

Or rather, tragicomic. I try to reproduce this in my<br />

art. Give the viewer a comical point of entry to the<br />

piece. On the other hand, I don’t want this to be too<br />

large a part of the artwork. It is just a way to attract<br />

the viewer’s attention and make him or her ‘listen’, just<br />

as it is in the blues. But as you make your way through<br />

the artwork or song the comedy disappears and the<br />

real subject, or feeling, takes hold.<br />

Howlin’ Wolf : I Asked for Water<br />

Oh, I asked her for water: she brought<br />

me gasoline.<br />

Oh, I asked her for water: she brought<br />

me gasoline.<br />

That’s the troublingest woo-hoo [woman],<br />

that I ever seen.<br />

The church bell tollin’, the hearse come<br />

driving slow.<br />

The church bell tollin’, the hearse come<br />

driving slow.<br />

I hope my baby, don’t leave me no more.<br />

Oh, tell me baby, when are you coming<br />

back home?<br />

Oh, tell me baby, when are you coming<br />

back home?<br />

You know I love you baby, but you’ve<br />

been gone too long.<br />

Repetition<br />

My works often contain an element of repetition. It<br />

is already present at the stage where I formulate the<br />

idea, when I keep asking myself: ‘Is this good enough,<br />

is it essential?’ over and over again. It becomes<br />

manifest in different ways. Sometimes in a purely<br />

physical way, like in my performance 191.4 (One<br />

Metre Higher than Turning Torso) where I feed out<br />

all 191.4 meters of a cord, one arm’s length at a time.<br />

At other times, what is repeated is the artwork itself,<br />

like Contaminated Thoughts, where a mirror illusion<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

reflects and repeats its own mirror image infinitely.<br />

Contaminated Thoughts<br />

The piece Contaminated Thoughts is a cube made<br />

of square one-way mirrors (50 x 50 cm) that houses<br />

a light bulb. The whole thing is on a platform made<br />

of wooden boards. The subject matter is thoughts –<br />

thoughts that are repeated and enlarged infinitely.<br />

A thought that never makes its way out, but that<br />

can be seen and felt from the outside. By letting the<br />

thought ‘see’ its own thought, its own self-image, but<br />

never really see anything else, it is made to grow in<br />

proportion. It creates its own universe, which becomes<br />

beautiful or dangerous, and sometimes both at once.<br />

Although this sculpture is made out of glass, you<br />

can’t see through it, so even if there is another viewer<br />

looking in on the other side of the cube, you both<br />

see nothing but the piece. This produces a sense of<br />

loneliness during the act of viewing. I want the viewer<br />

to be drawn into this feeling, sealing him or herself off<br />

from the world outside. In Contaminated Thoughts, I<br />

also use contrasts, like the contrast between the hard,<br />

rigid, and sterile material of glass, and the flexible,<br />

living, and rough wooden boards. There is also an<br />

inner contrast within the glass cube, between the<br />

claustrophobic actual space and the infinite illusory<br />

space created by the mirror. The claustrophobic mood<br />

I want to invoke, which is then contrasted within the<br />

illusion. That is how I feel when I subject myself to,<br />

or when I am subjected to, the kind of loneliness that<br />

you get from feelings like anxieties that have grown<br />

too strong to be handled.<br />

Two Sides of the Coin<br />

Two Sides of the Coin is a tunnel made from beams<br />

and chipboard, measuring 8.80 metres long and 2<br />

metres wide. The tunnel is divided into two 4.40<br />

metre sections by a 195 by 195 cm square of mirror<br />

glass. Two 15 W working lights are mounted in the<br />

top corners on either side of the glass. One half of<br />

the tunnel has been plastered, sanded and painted<br />

white. The lights in this section are always on. This<br />

means that this section is almost dazzlingly bright, as<br />

the walls and ceiling are white, and all you can see is<br />

yourself, your own mirror image.<br />

The other section of the tunnel is dark and rough,<br />

and the chipboard inside is left untreated. The lights<br />

in the corners of this section are turned off. And what<br />

you see here is not yourself, but the other section<br />

of the tunnel, which is visible through the glass.<br />

However, every 27 seconds the lights in here light up<br />

too, for just a second. And for that short moment, the<br />

people on both sides see themselves, but also see right<br />

through themselves, into the other section, through<br />

to the other person. The reflections are grey, almost<br />

spectral images.<br />

Seeing yourself, looking at yourself and your own<br />

mirror image can be good for you. I don’t mean that<br />

vanity is a good thing, I mean that you should see<br />

yourself objectively as the person you are, and not as<br />

the person you think you are or wish you were. When<br />

you are standing there, looking at yourself in this<br />

square mirror, and suddenly see that brief moment<br />

of suspecting that there is something there behind it.<br />

Maybe there was somebody else there? Maybe it was<br />

all in my imagination? Maybe I saw through myself?<br />

If you are standing on the other side of the piece<br />

you are looking at people who are not aware of you,<br />

seeing them standing there, looking at themselves,<br />

trying to understand. That gives the viewer a sense<br />

of power. A power that stays with you as long as you<br />

remain anonymous. And then goes away when the<br />

lights are turned on and you are blinded, seen and<br />

exposed. The disquieting sensation of not knowing<br />

just what is about to happen is strengthened when<br />

you are given a hint of light on the other side, or<br />

blinded by the bright lights and exposed in your<br />

position of power.<br />

22 23<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

24 25<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

26 27<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

Per Kristian Nygård<br />

Communication Breakdown<br />

It’s Always the Same 1<br />

My point of departure as an artist is being able to say<br />

something with my works, and that this something<br />

can be perceived or read through my works. More<br />

specifically, there must be something that can be<br />

decoded/interpreted or experienced in my works that<br />

gives the observer an inkling of what I want to say.<br />

In his Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious<br />

Sigmund Freud examines the way in which jokes<br />

work from a purely technical perspective. I see several<br />

similarities between works of art and jokes in terms<br />

of methodology, technique and psychology. Freud<br />

emphasises that a joke makes a point of something,<br />

and that this is achieved through the technique used<br />

to tell jokes. In his book, Freud examines different<br />

techniques that jokes employ to arrive at this point.<br />

If Freud’s theory about jokes is to have any relevance<br />

when transposed to works of art, then there must be<br />

something in art, too, that corresponds to this ‘point’.<br />

This is not contingent on whether the creative<br />

process is rational or irrational, because there is<br />

something strictly rational in attempts to work in an<br />

irrational manner. It is commonly assumed that an<br />

irrational way of working is linked to the emotions, to<br />

sensibilities. But this ‘something’ is not necessarily a<br />

feeling.<br />

I’m not an expressionist, I have nothing<br />

to express. 2<br />

History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it. 3<br />

I work in an artistic tradition where the artist<br />

himself can talk about his works. This means that the<br />

artist has a dual role, as both the architect of his work<br />

and as the commentator.<br />

Underlying all Western modes of analysis<br />

is a very strong rationalistic tendency –<br />

an assumption that everything can be<br />

accounted for. 4<br />

Thus begins a lengthy reply from the Dalai Lama<br />

to a question about a psychiatric case. Where his<br />

reasoning leads is of little interest in the context; he<br />

simply takes for granted that certain things cannot<br />

be explained and are too complex for any cause-andeffect<br />

relationship to be divined. However, this is a<br />

point of departure that is of no use to me and that<br />

tends towards a romantic tradition where the artist is<br />

merely a kind of medium in the creative process.<br />

The Problem of the Axiom?<br />

An axiom is a mathematical concept: a value or<br />

something else that must be accepted as being<br />

self-evident in order for the rest of an arithmetical<br />

problem to be correct, to be calculated successfully,<br />

or to be meaningful. Useful, right or wrong, an<br />

axiom will nevertheless provide meaning because it<br />

is accepted as being true or relevant. For example, if<br />

you accept that 2 + 2 = 4, no further demonstration<br />

is needed to define the properties of 2. The modality<br />

of 2 is of no significance for the result, and neither is<br />

it in any way decisive for the result if 2 is inspired or<br />

uninspired or depressed, etc. What is decisive in the<br />

context, however, is that we accept 2 as a valid value<br />

or modality, etc.<br />

By starting with a set of axioms it is thus<br />

possible to infer and prove so called theorems<br />

with the help of logical conclusions. 5<br />

The example above from the study of mathematics<br />

is a good example. With the help of this methodology,<br />

mathematics has succeeded in achieving quantifiable<br />

results. But what happens when a thought takes on an<br />

axiomatic character? The thought, for example, of the<br />

death of an author or the death of political art?<br />

Political <strong>Art</strong><br />

The French philosopher Jacques Rancière has had<br />

a great impact on the visual arts in recent years. His<br />

philosophy is multi-faceted, but here I would like to<br />

focus on his critique of political art, which has been<br />

widely discussed over the past few years. He continues<br />

in the footsteps of post-structuralist theorists, asserting<br />

that, since aesthetic experience is subjective, it is<br />

impossible to predict how it will move or affect the<br />

observer. In other words, there is no scientific proof<br />

to suggest that a radical, left-wing work of art will<br />

influence the observer to adopt a more socialist frame<br />

of mind.<br />

In the 1960s and 1970s the consensus was that<br />

art could indeed influence the observer. In the Soviet<br />

Union and the dictatorships of Eastern Europe this<br />

was an assumption that was beyond discussion.<br />

One has only to look at Ceaus¸escu’s propaganda in<br />

Romania or the many portraits of Saddam Hussein<br />

in Iraq. Consider also the intrinsic radicalism of<br />

printmaking, a radicalism that first and foremost was<br />

to be found in the medium itself. Printmaking enabled<br />

artists to mass-produce ‘art for the people’, and it was<br />

through this art that the people would be enlightened.<br />

In a nutshell, the idea was that political art would<br />

influence the observer in the direction that the artist/<br />

dictator wished.<br />

The point that Rancière seeks to make is that,<br />

as art is a sensual, heterogeneous experience, it is<br />

impossible to calculate what reaction this subjective,<br />

aesthetic experience will trigger. 6 <strong>Art</strong> cannot<br />

work instrumentally. <strong>Art</strong> can never be a collective<br />

experience, so, if it affects us at all, it will affect us<br />

in different ways. What happens when this thought<br />

assumes the character of an axiom? In other words,<br />

when it is accepted without question or no longer<br />

needs to justify its existence?<br />

28 29<br />

I have nothing to say and I’m saying it. 7<br />

Inherent in Western thinking is the idea that it<br />

is possible for us as individuals to communicate the<br />

body of our thoughts to others. This assumes that<br />

the body of thought is something good, and that<br />

others are willing to accept it and to embrace it as<br />

their own. In philosophy this is known as a logical<br />

fallacy – assuming that others, regardless of their<br />

circumstances, will act as we would do in a given<br />

situation. Even so, the belief that we can communicate<br />

is fundamental for the way we see the world.<br />

For instance, you have the constraints of the<br />

idea that everything can be explained within<br />

the framework of a single lifetime, (and you<br />

combine this with the notion that everything<br />

can and must be explained and accounted for). 8<br />

Equally fundamental is the idea that we<br />

are understood. It seems obvious to us that<br />

misunderstandings are nothing more than<br />

misunderstandings and are not ideological in<br />

character. Equally fundamental is the assertion that<br />

this project may be said to have failed. Consider, for<br />

example, the attempt to introduce democracy to Iraq.<br />

Somewhere along the line something went wrong…<br />

At the same time it feels like utter defeatism to indulge<br />

in the thought that communication is impossible.<br />

(Although anyone who has been in a long-term<br />

relationship will probably recognise themselves in just<br />

such a situation.).<br />

So, how do we communicate?<br />

A Work of <strong>Art</strong> – Borderline Design?<br />

Meaning and understanding in a work of art or an<br />

installation is established first and foremost through<br />

the work’s aesthetic frames of references and its own<br />

expression. Baby talk, for example, has no frames of<br />

reference to anything we recognise and so we perceive<br />

it as babble in which the communicative aspect is<br />

minimal. Alternatively, we can see it as a very basic<br />

form of communication that is able only to express<br />

two polarities – satisfied or dissatisfied. This makes it<br />

ill-suited to articulating more complex opinions.<br />

<strong>Art</strong> is an aesthetic experience, and here I am<br />

thinking primarily of aesthetic references. In other<br />

words, the way in which visual expression refers to<br />

an art-historical style, to popular culture/fashion,<br />

or to a historical era, for example, black-andwhite<br />

photographs that document performance<br />

art or installations. Take Gordon Matta Clark’s<br />

documentation of Splitting, for example (a split,<br />

two-storey house), or the works of Joseph Kosuth.<br />

What was once a contemporary standard (analogue<br />

35mm, black-and-white photography) has become<br />

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong>

<strong>2009–2010</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong><br />

an aesthetic standard for us that now refers to this<br />

period. If we see a nicely framed black-and-white<br />

photograph today, we may say (depending on<br />

the motif) that the aesthetics refer to minimalism<br />

or conceptual art or feminist art, etc. This effect<br />

is achieved through the aesthetic references, the<br />

presentation and the aesthetic first impression – antispectacular,<br />

anti-monumental and/or anti-aesthetic,<br />

as it is sometimes described.<br />

Minimalism ended up as a traditional object of<br />

taste – it just had a cooler taste. 9<br />

Joseph Kosuth says of the photograph in his<br />

work One and Three Chairs, which someone else<br />

had taken as a practice shot, that ‘this style lent a<br />

distance to the works that showed that it wasn’t a<br />

matter of compositions but of systems of meaning<br />

that I myself had constructed.’ 10 I came across<br />

an example of how well-established this idea has<br />

become in a review of the book Kjartan Slettemark<br />

– Kunsten å falle (‘Kjartan Slettemark – The <strong>Art</strong><br />

of Falling’), which says that ‘large numbers of<br />

the photographs in Kunsten å falle are in black<br />

and white, which makes the transition to colour<br />

photography towards the end of the book seem both<br />

abrupt and unconsidered.’ 11 In this example, the<br />

argument is that the colour photographs in the book<br />

mar the overall aesthetic.<br />

There are numerous references to what we<br />

often call minimalism and/or conceptual art in<br />

contemporary art. Exquisitely framed black-andwhite<br />

photographs act as a new Rococo frame.<br />

Another characteristic of conceptual art is that it is<br />

not open to interpretation. It is what it is: closed.<br />

One example is Sol Le Witt’s ‘instructions’ for wall<br />

drawings, which have nothing at all to do with<br />

interpretation, but are simply what they say they<br />

are – instructions. But these works refer only to the<br />

aesthetics, not to the content.<br />

Neo-Conceptualism/Borderline Design<br />

The assertion is that the idea is the most important<br />

thing, but what we often see is an aesthetic<br />

statement, a visual product where the underlying<br />

ideologies are no longer visible for us. The visual<br />

has taken over, establishing the standards to which<br />

we must now relate. It is this that is also referred to<br />

as ‘borderline design’. But this is only the aesthetic<br />

aspect of the work of art. Is there a method that with<br />

good reason leads there? Or are form and content<br />

inextricably interlocked? And, if so, will the form<br />

itself provide its own content? On the other hand,<br />

ceramics, for example, are not known for being<br />

particularly rich in content from a conceptual point<br />

of view…<br />

MFA 2 MFA 2<br />

At its core, the meaning of art consists in<br />

transposing communication to the field<br />

of perception. 12<br />

Methodology<br />

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, better known as<br />

Mahatma Gandhi, is famous for his development of<br />

the concepts of civil disobedience and non-violent<br />

protest. The entire array of his action is pacifist. It<br />

is based on non-violence, civil disobedience, and is<br />

non-antagonistic. This form of action is based on a<br />

fundamental and highly detailed understanding of<br />

the system within which one acts and which one<br />