1. Wayne Thiebaud's “Potrero Hill,” - Columbia University Graduate ...

1. Wayne Thiebaud's “Potrero Hill,” - Columbia University Graduate ...

1. Wayne Thiebaud's “Potrero Hill,” - Columbia University Graduate ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

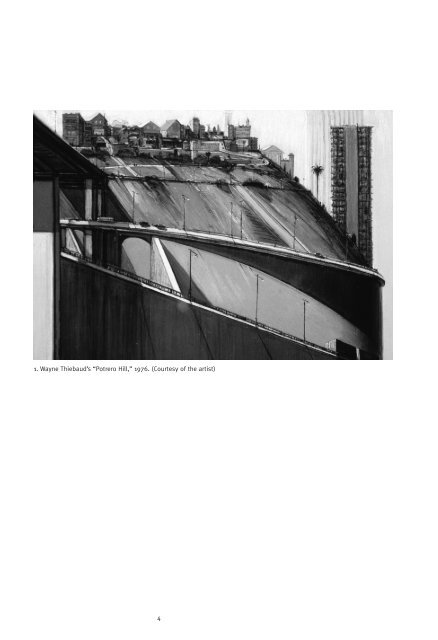

<strong>1.</strong> <strong>Wayne</strong> Thiebaud’s <strong>“Potrero</strong> <strong>Hill</strong>,<strong>”</strong> 1976. (Courtesy of the artist)<br />

4

Lauren Weiss Bricker<br />

Future Anterior<br />

Volume 1, Number 2<br />

Fall 2004<br />

History in Motion:<br />

A Glance at Historic Preservation<br />

in California<br />

California at the dawn of the 21st century is a restless place.<br />

Exponential population growth has translated into an unrelenting<br />

demand for affordable housing and road systems<br />

designed to efficiently link home with work. Between 1990 and<br />

2000 California’s diverse population increased by 13.8%, with<br />

the two regional areas of Los Angeles-Riverside-Orange<br />

Counties and San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose making up the<br />

second and fifth largest metropolitan areas in the country,<br />

respectively. 1 Historic preservation is frequently at the center<br />

of discussions within this climate of change, defending the<br />

view that often—though not always—there is value in the<br />

existing built environment. This attitude becomes particularly<br />

partisan when posited against the large financial investment<br />

entailed in virtually any development in the state’s inflated<br />

real estate market. These conditions are not unique to<br />

California; however, their scale and scope may be more<br />

extreme than what one finds elsewhere in the nation.<br />

Part of California’s evolving self-perception lies in the fastgrowing<br />

and controversial movement to preserve works of the<br />

“recent past,<strong>”</strong> i.e., works designed and constructed between<br />

the years 1945-65. In California, works of the recent past are<br />

seen as part of the state’s cultural patrimony, including many<br />

of the period’s iconic buildings and landscapes. Interest in the<br />

recent past is not limited to California. Nationwide, historic<br />

preservationists are treating works associated with the recent<br />

past with greater respect than ever before. Yet, as architectural<br />

historian Richard Longstreth has observed, many individuals<br />

accustomed to identifying historic buildings simply cannot see<br />

postwar works, since they typically lack one single focal point<br />

or vantage point from which a building can best be appreciated.<br />

2 Postwar architecture was born in a period where the ubiquitous<br />

presence of the automobile forced open an expanded<br />

spatial envelope. Visibility from the automobile promoted the<br />

creation of new auto-related building types, as well as dramatically<br />

impacting visual perceptions of the built environment.<br />

Contemporary artist <strong>Wayne</strong> Thiebaud captured this dynamic<br />

quality of speed in his depiction of commonplace features of<br />

the American landscape in his work <strong>“Potrero</strong> <strong>Hill</strong>,<strong>”</strong> (1976;<br />

Figure 1). 3<br />

In California, the individuals leading the charge for the<br />

preservation of the recent past are often newcomers to the<br />

5

field, particularly compared to other areas of preservation.<br />

Leadership for their activities in northern California emanates<br />

from the local chapter of DoCoMoMo (Documentation and<br />

Conservation of Buildings of the Modern Movement), based in<br />

San Francisco. In southern California, the Los Angeles<br />

Conservancy’s Modern Committee, or Modcom, as they are<br />

fondly known, is a feisty group of preservation advocates.<br />

Individual cities with important collections of postwar<br />

resources, most notably Palm Springs, have promoted the<br />

preservation of its historic modern buildings and, in the<br />

process, have made them part of their community’s image with<br />

benefits to the local tourism economy. Two years ago, the<br />

State Historic Resources Commission, formed a statewide<br />

committee to focus on historic architecture and landscape<br />

architecture of the modern age and issues peculiar to their<br />

preservation. This committee works closely with the State<br />

Historic Preservation Officer and staff to formulate preservation<br />

policy.<br />

The following case studies of current issues have been<br />

selected to illustrate the complexity of preservation of the<br />

recent past within the context of California’s social and economic<br />

conditions.<br />

Recognizing the Ethnic Heritage of Postwar<br />

Southern California: Holiday Bowl<br />

A particularly challenging situation for advocates of auto-oriented<br />

postwar architecture involves works whose significance<br />

derives from their association with cultural groups omitted<br />

from the mainstream of history. Efforts to preserve the Holiday<br />

Bowl and Coffee Shop (1957) placed preservation at the center<br />

of a desire to recognize and respect Los Angeles’ ethnically<br />

diverse community. The bowling alley and cafe was located in<br />

the Crenshaw District, northeast of Los Angeles International<br />

Airport, in the heart of the region’s aerospace industry and<br />

home to a vibrant Japanese- and African-American community<br />

since the 1920s. Advocates for the building, led by the Los<br />

Angeles Conservancy’s Modern Committee, saw it as a unique<br />

expression of the “rich cultural and social history of the<br />

Japanese-American community in Los Angeles.<strong>”</strong> A 1996 article<br />

published in The Los Angeles Times characterized the facility<br />

as “a kind of museum of tolerance, loyalty and optimism.<strong>”</strong> 4<br />

Despite these sentiments, the owners of the Holiday Bowl’s<br />

sought to clear the site and construct a “strip mall.<strong>”</strong> 5<br />

A protracted preservation effort resulted in the designation<br />

of the coffee shop, located at the front of the building<br />

(Figure 2), as a Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Monument, and<br />

the demolition of the bowling center behind it. The main reason<br />

for distinguishing the coffee shop from the rest of the<br />

6

2. Armet and Davis, architects; Helen<br />

Fong, interiors. Holiday Bowl and<br />

Coffee Shop (1957), Los Angeles,<br />

California. (Photo by Jack Laxer)<br />

building is that its exterior architecturally exemplifies a expressionist<br />

commercial mode, commonly known as “Googie,<strong>”</strong><br />

which currently enjoys a popularity rooted in the nostalgia of<br />

the 1950s. 6 Architects Louis Armet and Eldon Davis, leaders in<br />

the formulation of the style, designed the entire building<br />

including distinctive interior characteristics ultimately deemed<br />

less significant. These included a 32-lane bowling center, coffee<br />

shop and cocktail lounge/restaurant known as Sakiba.<br />

Holiday Bowl was built by four Japanese-America businessmen<br />

on land they leased. During the postwar period, the<br />

Crenshaw District re-established its community of Japaneseand<br />

African-Americans, embracing returning soldiers and<br />

Japanese-American families interned during the war. By the<br />

1950s, second and third generation Japanese-Americans had<br />

settled in the Crenshaw District, making it one of the largest<br />

Japanese-American communities in Los Angeles. One of the<br />

favorite forms of recreation in the community was bowling,<br />

which many Japanese-Americans took up before World War II,<br />

at the time when it was the fastest growing sport in the United<br />

States. 7<br />

At the Holiday Bowl, Japanese-American and African-<br />

American clientele were catered to in a variety of ways. The<br />

bowling alley was open twenty-four hours to accommodate<br />

the swing shifts of individuals working at local aerospace<br />

plants. Food service was an important part of the experience<br />

at the Holiday Bowl, especially during tournaments when participants<br />

might eat two meals on the premises. Originally the<br />

coffee shop served only western fare, but that was soon modified<br />

to meet the multi-ethnic tastes of the clientele. Among the<br />

dishes prepared by the cook were char siu pork and Louisiana<br />

hot links.<br />

The interior design of the coffee shop incorporated elements<br />

that enjoyed widespread popularity during the period,<br />

though not especially ethnic in origin. These included Charles<br />

7

3. Edward Durrell Stone, architect and<br />

Thomas Church, landscape architect.<br />

Stuart Company (1958), Pasadena,<br />

California. View of entrance façade.<br />

(Photo by Julius Shulman)<br />

and Ray Eames’ Wire-Base Side Chairs and Saucer Lamps<br />

designed by George Nelson. However, Sakiba, the cocktail bar<br />

and restaurant designed by Helen Fong, interior designer of<br />

the firm of Armet and Davis, incorporated several elements<br />

that were vaguely Japanese in origin. Fong suspended sculptures<br />

from the ceiling that were in the shape of the Japanese<br />

Islands and she attached iconic representations of the<br />

Japanese prefectures to the walls. 8<br />

The effort to preserve Holiday Bowl created coalitions<br />

across ethnic, social and cultural groups, and the issue<br />

brought forward a history that was little known outside the<br />

Crenshaw district. Articles appearing in the New York Times,<br />

Los Angeles Times, as well as The Rafu Shimpo published by<br />

the local Japanese American community, discussed the Holiday<br />

Bowl’s central role in the social life of the Crenshaw community.<br />

9 After decades of racial discrimination, Japanese and African<br />

Americans were able to enjoy a relaxed recreational atmosphere<br />

at Holiday Bowl. Unfortunately, by 2003, the cultural<br />

significance of Holiday Bowl was undervalued by a number of<br />

local decision-makers. One councilman dismissed its ethnic<br />

associations as merely of “sentimental value, but it’s got no<br />

historical value. It’s a blight in the neighborhood.<strong>”</strong> 10 The ultimate<br />

loss of Holiday Bowl points to the need to develop more<br />

effective ways to protect places associated with ethnic and<br />

cultural groups, whose significant historical roles have only<br />

recently been recognized.<br />

Integrated Landscape and Architecture:<br />

Stuart Company, Pasadena<br />

The City of Pasadena promotes its community with iconic<br />

images derived from its Arts and Crafts period neighborhoods<br />

and Beaux-Arts Civic Center. These representations of the preindustrial<br />

world subtly distinguish Pasadena from nearby Los<br />

Angeles, whose ambitious and at times unruly identity derives<br />

8

from its role as a major commercial and manufacturing center.<br />

However, industrialization did have its moment in Pasadena’s<br />

history; during the postwar period, the Pasadena Chamber of<br />

Commerce encouraged manufacturers, especially those associated<br />

with scientific instruments, precision products, scientific<br />

research and light industry to establish facilities in the city.<br />

In response to this invitation, a number of the firms relocated<br />

to Pasadena, or were newly established in the eastern<br />

section of the city where land available for larger plants existed,<br />

along with nearby acreage for housing tracts to accommodate<br />

a projected influx of new employees. 11 Without question<br />

the complex that most fully embodies the concept of the postwar<br />

“suburban factory<strong>”</strong> in Pasadena is the Stuart Company<br />

(1958), a pharmaceutical manufacturing facility and office<br />

building designed by architect Edward Durrell Stone and landscape<br />

architect Thomas Church (Figure 3). 12 The American<br />

Institute of Architects recognized their successful collaboration<br />

at the time, designating it one of the best buildings of 1958. 13<br />

The Stuart Company building was constructed for the<br />

manufacture and distribution of “diversified ethical pharmaceuticals.<strong>”</strong><br />

14 Set back 150 feet from Foothill Boulevard, a main<br />

arterial road, the massive building footprint, which occupies<br />

about one quarter of its 9.4 acre site, appears modest and<br />

fragile. This effect was achieved by setting the building into<br />

the sloped site, with the highest portion facing Foothill<br />

Boulevard. From the road, the complex reads a series of low,<br />

horizontally-oriented elements, exemplifying the type of architecture<br />

Longstreth notes may be invisible to some individuals.<br />

Church designed a landscape consisting of planters, lawn and<br />

a shallow pool. Stone’s building hovers above the setting like<br />

a floating classical pavilion. His signature cast concrete block<br />

screen stretches across the width of property, unifying the<br />

building façade with a series of adjacent parking bays.<br />

The grade of the property drops allowing the insertion of<br />

a second, lower floor. The main floor houses office, laboratory<br />

and storage space; the manufacturing processes are located<br />

below. A gracious atrium with an open staircase internally<br />

links the upper floor with a garden court and dining lounge.<br />

Externally, a swimming pool surrounded by a terrace, pool<br />

house and shade pavilion complete the composition. In<br />

their collaborative design for the Stuart Company, Church and<br />

Stone captured the spirit of corporate patriarchy of their<br />

client, Arthur O. Hanisch, Stuart Company’s original owner,<br />

who wanted to:<br />

9<br />

...build a completely new building concept. He wanted<br />

his building to conform to the landscaping, not in<br />

the general California way but in a way that would

10<br />

combine timeless beauty with increased efficiency<br />

and a utilization of the Southern California climate to<br />

make for maximum comfort for his employees, both<br />

in working and recreation areas.15<br />

The Stuart Company was eventually sold, in 1991 to<br />

Johnson and Johnson/Merck Pharmaceuticals Co., and later<br />

acquired by a public agency, the Metropolitan Transit Authority<br />

(MTA) around 1994. Out of concern for the fate of the building,<br />

Pasadena Heritage, the local historic preservation non-profit<br />

organization, prepared a National Register nomination for the<br />

property, which was finally listed in 1998.<br />

Although the Stone building was called out as significant,<br />

the discussion of Church’s contribution to the site by the nomination’s<br />

author was perplexing. The Stuart Company property<br />

is grouped with Church’s design for the Technical Center for<br />

General Motors (1956) in Warren, Michigan as one of his “bestknown<br />

large-scale projects,<strong>”</strong> but is not considered significant<br />

in the area of landscape architecture. The author of the nomination<br />

asserts that its landscape architecture “does not possess<br />

exceptional significance on its own, but may become eligible<br />

once it reaches the 50-year mark.<strong>”</strong> Landscape historian<br />

Charles Birnbaum’s interpretation of this devaluation of<br />

Church’s contribution to the project is consistent with the<br />

“invisibility<strong>”</strong> of modern landscape architecture for many<br />

involved with the documentation of historic sites. 16 Aside from<br />

the unfortunate disaggregation of landscape and architecture<br />

from the standpoint of the project’s design concept and its<br />

history (Church recommended Stone to the client), this assessment<br />

makes the landscape vulnerable in future rehabilitation<br />

projects of the historic property. 17<br />

In 2000, the City completed its East Pasadena Specific<br />

Plan (the Plan) in preparation for development near a new<br />

light rail service linking Pasadena with downtown Los Angeles.<br />

Originally MTA planned to construct a transit station on the<br />

site of the Stuart Company building (hence the purchase of<br />

the site), but at this point, they have limited their involvement<br />

to building a parking structure between the Stuart Company<br />

and the freeway. One of the commendable goals of the Plan is<br />

to promote Transit Oriented Development (TOD), and specifically<br />

to encourage mixed-use or residential development. The<br />

Plan calls for four hundred housing units to be constructed<br />

within the area that includes the Stuart Company site stating<br />

that the “preservation of the most significant portions of the<br />

Stuart Company building and its landscape [are] mandatory<strong>”</strong><br />

(the inclusion of landscape is noteworthy given the ambiguous<br />

language of the National Register nomination). 18 However,<br />

the rear portions of the building (effectively fifty percent of the

original structure) “may be removed to facilitate adaptive use<br />

and preservation of the more visible and architecturally significant<br />

portions of the building.<strong>”</strong> Clearly, the rear and less “significant<strong>”</strong><br />

portions of the Stuart Company were anticipated to<br />

be a site for new development.<br />

A private developer has come forward with a concept to<br />

develop 188 one- to three-bedroom and loft units, with parking<br />

for 296 vehicles. Approximately 39,000 square feet of the<br />

existing Stuart Company building is projected to be demolished.<br />

In its place will be four stories of housing above one to<br />

two levels of parking. Two to three stories of housing will<br />

wrap around the east side of the property, framing the pool<br />

area. The project sponsor is intending to apply for historic<br />

preservation tax certification, which, if granted, would allow it<br />

to apply a 20% tax credit against the cost of rehabilitation to<br />

the property. To qualify for the tax credits, the project needs to<br />

meet the criteria established by the Secretary of the Interior’s<br />

Standards for Rehabilitation. 19<br />

The project, as reflected in recent documents, is extremely<br />

sensitive in its treatment of the front portions of the buildings.<br />

Detailed analysis of the physical condition of deteriorated<br />

exterior and interior portions of the building, and appropriate<br />

treatments have been carefully identified. Similarly, the landscape<br />

treatment for the planters and other areas visible from<br />

Foothill Boulevard, which are overgrown, appears to be carefully<br />

assessed. 20 Unfortunately, the demolition of the rear portion<br />

of the building makes it difficult to understand how such<br />

a treatment could meet the federal standards for rehabilitation.<br />

Additionally, the new construction bears little relation or<br />

response to Stone’s architecture; neither in composition nor<br />

detailing does it respond to the imagery of the historic building.<br />

Also problematic is the treatment of the pool area. In the<br />

new project, the pool will remain but the bathhouse will be<br />

demolished, and new vegetation will be added. The shade<br />

pavilion will be relocated to a site adjacent to the parking<br />

structure. The new landscape features are characteristic of a<br />

southern California’s Mediterranean landscape tradition rather<br />

than a response to Church’s Modern aesthetic.<br />

The Stuart Company site is an excellent example of the<br />

interrelationship between landscape and architecture in postwar<br />

industrial projects, and the expanded spatial envelope<br />

associated with vehicular visibility is given full play in this<br />

project. If the proposed treatment is accepted as a preservation<br />

solution, one may wish to raise questions about the<br />

extent to which it will compromise the property’s integrity for<br />

the sake of responding to our current needs.<br />

Both the Holiday Bowl and the Stuart Company convey<br />

the historic and aesthetic issues associated with postwar<br />

11

California. Our increasing understanding of the expressive<br />

and cultural values of these works will strengthen the ability<br />

to advocate for their retention, an especially challenging<br />

endeavor within the current over-priced real estate market in<br />

California. Perhaps more significantly, however, is a failure to<br />

appreciate the complete compositions and dynamic visual<br />

perspectives inherent in postwar architecture, resulting in<br />

the partial demolition of buildings while claiming a preservation<br />

victory. In the case of the Holiday Bowl, a sophisticated<br />

architectural statement uniquely connected to the region’s<br />

ethnic community was severely compromised in the loss of<br />

its bowling alley and restaurant in favor of preserving its<br />

“Googie<strong>”</strong> style coffee shop. The Stuart Company suffers a<br />

similar fate, despite the sensitive treatment of its front portions,<br />

loosing much of its critical landscape composition and<br />

rear portion, this time in the name of adaptive re-use. Until<br />

we as preservationists are better prepared to set guidelines<br />

for the treatment of these examples of “recent history,<strong>”</strong><br />

many of these significant buildings of California’s postwar<br />

modernism will continue to be undermined by development<br />

interests and misguided public policy.<br />

Author biography<br />

Lauren Weiss Bricker, Ph.D is an Associate Professor of Architecture at the<br />

California State Polytechnic <strong>University</strong>, Pomona and director of the Archives-Special<br />

Collections in the College of Environmental Design, Cal Poly Pomona. She maintains<br />

a consulting practice in architectural history. Dr. Bricker is Vice-Chair of the<br />

State Historic Resources Commission in California, and co-chair of the<br />

Commission’s Committee on the Cultural Resources of the Modern Age. She is the<br />

recipient of a fellowship from the Clarence S. Stein Institute of Urban and<br />

Landscape Studies (2004) to support her research on The Pragmatists, a study of<br />

the American response to the form and ideology of European Modernism. Dr.<br />

Bricker has received support for her research from the Historical Society of<br />

Southern California/Haynes Foundation, the Institute for Environmental Design, Cal<br />

Poly Pomona, and was also a Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at the<br />

Huntington Library. She is a co-author of a forthcoming volume on the<br />

Mediterranean House in America (Harry N. Abrams, New York).<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 California has the nation’s largest populations of Hispanic or Latinos (1<strong>1.</strong>8%),<br />

Asians (3.7%), Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders (.117%) and American Indians<br />

(.333%). <br />

2 Richard Longstreth, “I Can’t See It; I Don’t Understand It; and It Doesn’t Look Old<br />

To Me,<strong>”</strong> in Preserving the Recent Past, ed. Deborah Slaton and Rebecca A. Shiffer<br />

(Washington, D.C.: Historic Preservation Education Foundation, 1995), 1-15-20.<br />

3 See also Edward Ruscha’s Thirty Four Parking Lots in Los Angeles, n.p., 1967.<br />

4 Peter Y. Hong, “Another Kind of Holiday Bowl Tradition,<strong>”</strong> Los Angeles Times. 2<br />

January 1996, B<strong>1.</strong><br />

5 John English, “Coalition Fights to the End for the Holiday Bowl,<strong>”</strong> Conservancy<br />

News 26, no. 2 (March/April 2004), 2.<br />

6 Alan Hess, Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture, (San Francisco: Chronicle<br />

Books, 1986).<br />

7 Beginning in 1916, individuals of color were excluded from the American Bowling<br />

Congress (ABC), the parent organization of the sport. African-Americans formed the<br />

National Negro Bowling Association in 1939. Soon after World War II, Japanese<br />

Americans followed their example by creating the Japanese-America Citizens<br />

League (JACL). See Gail Dubrow with Donna Graves, “Holiday Bowl,<strong>”</strong> in Sento at<br />

Sixth and Main, (Seattle: Seattle Arts Commission, 2002), 176. On the history of<br />

12

owling in the United States see Andrew Hurley, Diners, Bowling and Trailer Parks:<br />

Chasing the American Dream in the Postwar Consumer (New York: Basic Books,<br />

2001).<br />

8 Dubrow and Graves, 192.<br />

9 For example, see Scott Kurashige, “Can Holiday Bowl Be Saved?<strong>”</strong> The Rafu<br />

Shimpo, 5 May 2000; John Saito, Jr., “End of an Era: Holiday Bowl, 1958-2000,<strong>”</strong><br />

The Rafu Shimpo, 12 May 2000.<br />

10 Jeffrey Gettleman, “Panel Wants Bowling Alley Preserved,<strong>”</strong> Los Angeles Times, 7<br />

July 2000.<br />

11 “War Years and Development of High Tech Industries,<strong>”</strong> East Pasadena Specific<br />

Plan, City of Pasadena, 23 October 2000. 2-2, 2-3. A number of relocated or newlyformed<br />

firms had important ties with the aerospace industry, e.g., Jet Propulsion<br />

Laboratory, the consolidated Engineering Corporation, whose space technology<br />

was used in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Space Shuttle programs.<br />

12 The most complete history of the Stuart Company building is documented in its<br />

National Register Nomination, prepared by Alan Hess for Pasadena Heritage, 1994.<br />

13 “Architects Institute Selects Best Building Design of Year,<strong>”</strong> New York Times, 25<br />

May 1958.<br />

14 This term encompassed analgesics, vitamins, diet-control aids, tranquilizers and<br />

products for gastro-intestinal therapy. “The Pasadena Stuarts … The Royal Family<br />

of Pharmaceuticals,<strong>”</strong> The Investor, c. 1958. Stuart Company File, Design and<br />

Historic Preservation Library, City of Pasadena.<br />

15 “Story of Stuart: As Reported by a National Magazine,<strong>”</strong> reprint by Stuart<br />

Company from Good Packaging-Western Packaging Yearbook, July 1958, n.p.<br />

16 Charles A. Birnbaum, “A Status Report on Preserving and Interpreting Modern<br />

Landscape Architecture: Recent Developments in California and Beyond,<strong>”</strong><br />

Preserving the Recent Past. 2, 2-159-2-166.<br />

17 Hanisch told Church that he did not want a California architect; Church recommended<br />

Stone, a New York-based designer who was working, at the time, on the<br />

Stanford <strong>University</strong> Medical Center in Palo Alto (another collaborative project with<br />

Church, completed in 1959). Stone was enjoying considerable public attention,<br />

having recently completed the United States Embassy in New Delhi. For a contemporary<br />

biography, see Winthrop Sargeant, “Profiles: From Sassafras Branches,<br />

Edward D. Stone,<strong>”</strong> New Yorker, 3 January 1959. 32-34, 35, 38-49. The Embassy and<br />

the Stanford Medical Center share a number of features with the Stuart Company<br />

building, as exemplars of a new “formalism.<strong>”</strong> See William Jordy, “The Formal<br />

Image: USA,<strong>”</strong> Architectural Review 127 (March 1960); 157-165.<br />

18 East Pasadena Specific Plan, City of Pasadena, 23 October 2000. 5-3.<br />

19 Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation of Historic Buildings, rev.<br />

ed. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1990).<br />

20 An explanation and analysis of the trees and shrubs that have survived at the<br />

Stuart Company is included in a study by Joan Woodward. See her forthcoming<br />

article: “Letting Los Angeles Go: Lessons from Feral Landscapes,<strong>”</strong> Landscape<br />

Review 10(1) 2004.<br />

13