Exhibition Review: Robert Moses and the Modern City - Columbia ...

Exhibition Review: Robert Moses and the Modern City - Columbia ...

Exhibition Review: Robert Moses and the Modern City - Columbia ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

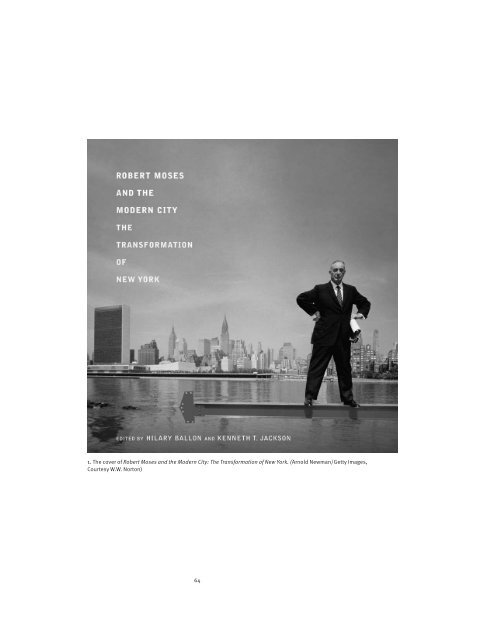

1. The cover of <strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong>: The Transformation of New York. (Arnold Newman/Getty Images,<br />

Courtesy W.W. Norton)<br />

64

<strong>Exhibition</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

R<strong>and</strong>all F. Mason<br />

Future Anterior<br />

Volume IV, Number 1<br />

Summer 2007<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> University historians Hilary Ballon <strong>and</strong> Kenneth<br />

Jackson <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir colleagues deserve high praise. Their revisionist<br />

project, which documents <strong>and</strong> debates <strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong>,<br />

is characterized by superb scholarship spread across three<br />

museum exhibits, a website, lectures, panels, <strong>and</strong> a catalogue,<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong>: The Transformation<br />

of New York. The three exhibits are “<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong>: Slum Clearance <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Superblock Solution” at<br />

<strong>the</strong> Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at <strong>Columbia</strong> University;<br />

“<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong>: The Road to Recreation”<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Queens Museum of Art; <strong>and</strong> “<strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong>” at <strong>the</strong> Museum of <strong>the</strong> <strong>City</strong> of New York.<br />

This season of <strong>Moses</strong> confirms that he left a wonderful<br />

legacy—dozens of places of lasting public value. The exhibits<br />

<strong>and</strong> catalogue will be acknowledged as essential material for<br />

<strong>the</strong> education of planners, urban designers, politicians <strong>and</strong><br />

urbanists of all stripes. <strong>Moses</strong> had enormous effect on <strong>the</strong><br />

New York materially (<strong>the</strong> buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes), politically<br />

(empire building, bullying, alienating “<strong>the</strong> people”), <strong>and</strong><br />

culturally (we are still talking about him, due to <strong>Robert</strong> Caro’s<br />

The Power Broker as well as <strong>the</strong> current exhibits). 1 In all <strong>the</strong>se<br />

senses, <strong>Moses</strong>’ legacy is obvious <strong>and</strong> extensive.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> discussion surrounding his character—cast in<br />

<strong>the</strong> formulation “Was he a good or a bad man?”—is a red herring.<br />

The serious question ventured by <strong>the</strong> exhibits is what we<br />

should remember <strong>and</strong> learn from <strong>Moses</strong>, his built works, <strong>and</strong><br />

his political agility. Or, taking <strong>the</strong> current exhibits <strong>and</strong> scholarship<br />

on <strong>the</strong>ir own ground, how should <strong>Moses</strong> be remembered?<br />

The assembled scholars behind this project recognize <strong>Moses</strong>’<br />

incredible legacy without bowing before it. The legacy is h<strong>and</strong>led<br />

evenh<strong>and</strong>edly, though <strong>the</strong> balance sheet is positive, a<br />

different <strong>and</strong> welcome take from Caro’s until-now canonical view.<br />

Each school of thought, though, is a sign of its time. Caro<br />

wrote in <strong>the</strong> aftermath of <strong>the</strong> denouement of <strong>Moses</strong>’ downfall,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> cynicism it rightly engendered about powerful government<br />

agency. Ballon, Jackson, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir collaborators write in<br />

a period of renewed confidence about public-sector building<br />

<strong>and</strong> acceptance of community will as part of <strong>the</strong> city-building game.<br />

Apart from <strong>Moses</strong>’ legacy, one would expect <strong>the</strong>se eminent<br />

historians to dwell on <strong>Moses</strong>’ own history. Yet little<br />

interest is shown in where <strong>Moses</strong> came from, what legacies<br />

65

he inherited, on whose shoulders he stood—on what came<br />

“before <strong>Moses</strong>” <strong>and</strong> enabled his full flowering. The exhibits<br />

convey <strong>the</strong> message that <strong>Moses</strong> sprang, fully formed—brilliant<br />

though flawed—to his perch on <strong>the</strong> steel beam comm<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

<strong>the</strong> city. (Figure 1)<br />

The Exhibits<br />

The three complementary exhibits are impressive in scope <strong>and</strong><br />

scale. They document <strong>the</strong> vast reach of <strong>Moses</strong>’ influence by<br />

showcasing his projects: roads, parks, pools, housing complexes,<br />

urban renewal schemes. The Wallach Gallery focuses<br />

on <strong>the</strong> clearance <strong>and</strong> modernist design of urban renewal<br />

schemes; <strong>the</strong> Museum of <strong>the</strong> <strong>City</strong> of New York on roads,<br />

bridges <strong>and</strong> parks; <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Queen Museum of Art on recreational<br />

projects such as beaches, pools, <strong>and</strong> playgrounds. The<br />

ensemble of <strong>Moses</strong>’ works definitively transformed New York<br />

from a walking <strong>and</strong> transit city into <strong>the</strong> automobile metropolis<br />

of today. They created a sense of mobility fueling a metropolitan<br />

sense of <strong>the</strong> region while infusing dense <strong>and</strong> rebuilt neighborhoods<br />

with park infrastructure.<br />

The design of <strong>the</strong> exhibits varies in quality <strong>and</strong> effectiveness,<br />

ranging from <strong>the</strong> simple, careful, <strong>and</strong> surprisingly lovely<br />

display of original documents at <strong>Columbia</strong>, to <strong>the</strong> hastily<br />

constructed <strong>and</strong> cheap Museum of <strong>the</strong> <strong>City</strong> of New York installations.<br />

The organization <strong>and</strong> design of <strong>the</strong> vast exhibit at <strong>the</strong><br />

Queens Museum is particularly clear, affording <strong>the</strong> space for<br />

inspection as well as reflection on <strong>the</strong> many historical photographs<br />

<strong>and</strong> graphics. Andrew Moore’s large-format color<br />

photographs, parceled across <strong>the</strong> three exhibits, match <strong>the</strong><br />

clarity <strong>and</strong> power of <strong>Moses</strong>’ vision, though without hubris. The<br />

photographs document <strong>the</strong> quality design as well as <strong>the</strong> contemporary<br />

social values <strong>the</strong> places continue to nurture—more<br />

than pretty pictures of good design, <strong>the</strong>y capture people using<br />

<strong>the</strong> places, such as kids swimming at <strong>the</strong> well-loved pools.<br />

The dozens of projects shown in <strong>the</strong> exhibits are best<br />

described as muscular. Many of <strong>the</strong>m asserted modernism as<br />

a new <strong>and</strong> confident language for public works, particularly<br />

<strong>the</strong> pools <strong>and</strong> housing towers by some of <strong>the</strong> leading midtwentieth-century<br />

architects including I.M. Pei <strong>and</strong> Wallace<br />

Harrison. Each required massive amounts of labor, material<br />

<strong>and</strong> dollars; <strong>the</strong> bridges <strong>and</strong> highways transcended <strong>the</strong><br />

natural <strong>and</strong> human geography of region, crossing rivers <strong>and</strong><br />

clearing neighborhoods. <strong>Moses</strong>’ projects—<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir shaping<br />

of New York’s l<strong>and</strong>scape—were all business, even when <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were really about play. But many were also beautiful, including<br />

some projects never completed: what fan of mid-century<br />

modernism doesn’t secretly wish that an unbuilt Edward Durell<br />

Stone pavilion were presently st<strong>and</strong>ing in Central Park?<br />

66

2. Title I Slum Clearance Progress,<br />

April 16, 1956. (Avery Library Archives,<br />

Courtesy W.W. Norton)<br />

<strong>Moses</strong> understood <strong>the</strong> power of visual communication<br />

through models, brochures, <strong>and</strong> constant press attention.<br />

The exhibits build upon <strong>Moses</strong>’ own propag<strong>and</strong>a to make <strong>the</strong><br />

visual argument for <strong>Moses</strong>’ historical significance extremely<br />

well, though a sense of <strong>the</strong> historical narrative is left for <strong>the</strong><br />

catalogue, which is an essential companion to <strong>the</strong> exhibits.<br />

(Figure 2)<br />

While <strong>the</strong> urbanistic expression of <strong>Moses</strong>’ work is<br />

brilliantly displayed, a correspondingly thorough account<br />

of <strong>Moses</strong>’ political works is missing from <strong>the</strong> exhibits. The<br />

administrative architectures he employed, his boldness<br />

in deploying <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>and</strong> his personal political skills are not<br />

conveyed. Likewise, only a weak sense of <strong>the</strong> community<br />

opposition, so important to shaping our memory of <strong>Moses</strong>,<br />

is included. The narratives are <strong>the</strong>re—regarding Washington<br />

Square Park, for example—but <strong>the</strong> opposition tends to get<br />

lost, or cartooned, in <strong>the</strong> exhibits. Politics <strong>and</strong> community<br />

opposition usually are not as visually interesting as master<br />

building, so perhaps <strong>the</strong>re is little surprise that <strong>the</strong> exhibits<br />

are weaker on this topic.<br />

67

The Catalogue<br />

Ballon <strong>and</strong> Jackson’s catalogue is superb in every regard, <strong>and</strong><br />

spares <strong>the</strong> exhibits from most weaknesses <strong>and</strong> elisions. The<br />

book’s portfolio of photographs, drawings <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r graphics<br />

from <strong>the</strong> exhibit, with accompanying dossiers <strong>and</strong> capsule histories<br />

of individual projects, gives one <strong>the</strong> take-home exhibit.<br />

And it collects a set of rich, clear, <strong>and</strong> relatively brief essays<br />

by leading scholars, who use <strong>Moses</strong> as an axis to spin out <strong>the</strong><br />

contexts in which he operated—<strong>the</strong>y don’t fetishize Big Bob<br />

<strong>the</strong> Builder, while remaining centered on his successes <strong>and</strong><br />

failures. 2 The authors match <strong>Moses</strong>’ muscular legacy of public<br />

works with <strong>the</strong>ir own forceful <strong>and</strong> carefully researched analyses.<br />

They rebuild <strong>Moses</strong>’ story with balance <strong>and</strong> depth, restoring<br />

what was lost in Caro’s enthusiastic but cynical reconstruction.<br />

Jackson begins by presenting <strong>the</strong> argument for revisiting<br />

Caro’s interpretation of <strong>Moses</strong>. It is even-h<strong>and</strong>ed, <strong>and</strong><br />

puts <strong>Moses</strong>’ entire mid-century moment in historical context.<br />

Owen Gutfreund’s essay does <strong>the</strong> best job of giving <strong>Moses</strong><br />

a history before his moment, emphasizing, for instance, <strong>the</strong><br />

design precedents <strong>Moses</strong> copied (<strong>the</strong> Bronx River Parkway, for<br />

instance) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> public benefit corporation model of administration<br />

he adapted. Built on <strong>the</strong> historical <strong>and</strong> contemporary<br />

contexts out of which <strong>the</strong> master builder emerged, Gutfreund<br />

concludes, “<strong>Moses</strong> was <strong>the</strong> right person in <strong>the</strong> right place at<br />

<strong>the</strong> right time. He did not invent a vision of a novel New York<br />

from whole cloth, but instead he deftly appropriated innovations<br />

<strong>and</strong> plans of o<strong>the</strong>rs, adapting <strong>and</strong> combining <strong>the</strong>m to<br />

suit his purposes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n readapting <strong>the</strong>m as circumstances<br />

changed.” 3 Or, as Jackson puts it: “What made [<strong>Moses</strong>] unusual<br />

was not <strong>the</strong> originality of his thought but <strong>the</strong> personal qualities<br />

that allowed him to build where o<strong>the</strong>r could only dream.<br />

<strong>Moses</strong> <strong>the</strong> visionary was second rate; <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>the</strong> builder was<br />

in a class by himself.” 4<br />

The ever-present reality of racial discrimination, not just<br />

in <strong>Moses</strong>’ psyche but also as a social structure of <strong>the</strong> period, is<br />

prominently included in Martha Biondi’s essay. Marta Gutman<br />

takes up one set of <strong>Moses</strong>’ vast works—recreational projects<br />

such as pools <strong>and</strong> beaches <strong>and</strong> playgrounds—sensitively, considering<br />

race <strong>and</strong> how it should shape our memory of <strong>Moses</strong>.<br />

Joel Schwartz’s posthumous thoughts couch <strong>Moses</strong> thoughtfully<br />

in <strong>the</strong> history of efforts to plan New York in <strong>the</strong> first half of<br />

<strong>the</strong> twentieth century.<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> Fishman’s persuasive essay highlights Washington<br />

Square Park (Figures 3 <strong>and</strong> 4) as a watershed conflict not just<br />

in <strong>Moses</strong>’ career but in American urbanism—marking <strong>the</strong><br />

arrival of community voices <strong>and</strong> grassroots participation as<br />

new, transformative partners in <strong>the</strong> urban process. Like his<br />

colleagues in <strong>the</strong> book, Fishman draws compelling evidence<br />

68

3. Comparative plans of Washington<br />

Square Park with <strong>Moses</strong>’ proposed<br />

alterations on <strong>the</strong> right. (New York<br />

Times, Mar. 11, 1955, Courtesy W.W.<br />

Norton)<br />

from <strong>the</strong> archives, unfolding <strong>the</strong> scenes in which <strong>the</strong> politics of<br />

<strong>the</strong> day, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Moses</strong>’ politicking, play out as a game, a game in<br />

which <strong>Moses</strong> begins his career-ending losing streak.<br />

These essays work toge<strong>the</strong>r to create a masterful analysis<br />

of <strong>Moses</strong>’ moment. But from where did this moment come?<br />

The historians should be stronger on this <strong>the</strong>me. <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

his opponents, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> resources he used did not appear<br />

all at once in <strong>the</strong> 1930s. They emerged out of decades of <strong>the</strong><br />

city’s development, on <strong>the</strong> efforts of countless reformers,<br />

visionaries, <strong>and</strong> designers, <strong>and</strong> from contingencies quite<br />

outside of <strong>Moses</strong>’ control. The historians let <strong>Moses</strong>’ giant<br />

shadow obscure <strong>the</strong>se important precedents <strong>and</strong> foundations.<br />

Gutfreund touches <strong>the</strong>se bases <strong>the</strong> best, <strong>and</strong> most of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

chapters build some sense historical precedent, but <strong>the</strong> exhibits<br />

fail to communicate this, <strong>and</strong> leave <strong>the</strong> giant exposed—in<br />

his glory <strong>and</strong> infamy—but without enough historical narrative<br />

or context to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> origin of <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> his moment.<br />

Myths <strong>and</strong> Legacies<br />

There is romanticizing on all sides of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> debates: celebrators<br />

picture <strong>the</strong> figure on <strong>the</strong> cover of <strong>the</strong> book—virile, in<br />

charge, a force of nature, damning those who dared to st<strong>and</strong><br />

in his way; detractors find an easy villain. All of which leaves<br />

69

4. Hulan Jack’s revised proposal of<br />

a roadway in Washington Square<br />

Park. (New York Times, May 18, 1957,<br />

Courtesy W.W. Norton)<br />

a great deal of important history <strong>and</strong> urbanism unrecognized,<br />

or worse, obscured. The exhibits perpetuate <strong>the</strong> myth that<br />

only big, new construction projects are worthy of historians’<br />

attention <strong>and</strong> of public notice, though <strong>the</strong> catalogue’s essays<br />

give <strong>the</strong> reader many reasons to doubt <strong>the</strong> myth. The romantic<br />

Janus-like figure of <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>the</strong> Villain–<strong>Moses</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hero blots<br />

out important narratives about building New York that are<br />

worth remembering <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

The exhibits have little to suggest <strong>the</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> evolved<br />

out of any tradition or that he built upon foundations laid by<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs. But he did not spring, fully formed, upon <strong>the</strong> scene in<br />

1934. And his design ideas as well as political strategies owed<br />

great debts to those who preceded him. Quasi-governmental<br />

commissions (also called public benefit corporations) created<br />

<strong>the</strong> political space <strong>Moses</strong> later occupied so brilliantly with<br />

<strong>the</strong> largesse of federal funds he amassed. The commissions<br />

responsible for Central Park, preservation of <strong>the</strong> Palisades,<br />

reform of <strong>the</strong> police <strong>and</strong> housing commissions, <strong>and</strong> many o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

far predated <strong>Moses</strong>, most prominent among <strong>the</strong>m Andrew<br />

Haswell Green (1820-1903). Though Green is mostly forgotten<br />

today, his long <strong>and</strong> illustrious career, spanning <strong>the</strong> sec-<br />

70

ond half of <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century, included key roles in <strong>the</strong><br />

building of Central Park, <strong>the</strong> creation of <strong>the</strong> New York Public<br />

Library, <strong>the</strong> preservation of Niagara Falls <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palisades,<br />

<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r projects to build or preserve great public works in<br />

<strong>and</strong> around New York. Of greatest moment, Green was known<br />

as <strong>the</strong> “fa<strong>the</strong>r of Greater New York,” for his advocacy of <strong>the</strong><br />

consolidation of <strong>the</strong> city finally achieved in 1898. Green also<br />

formed <strong>the</strong> American Scenic <strong>and</strong> Historic Preservation Society<br />

in 1895, a state-chartered non-profit group at <strong>the</strong> center of <strong>the</strong><br />

New York’s nascent historic preservation field in <strong>the</strong> early twentieth<br />

century.<br />

The emergence of parkways is swept under <strong>the</strong> wheels of<br />

traffic on <strong>Moses</strong>’ many road projects, even though he merely<br />

applied ideas already formed by o<strong>the</strong>rs. Yes, l<strong>and</strong>scape architect<br />

Gilmore Clarke gets a cameo appearance as a designersoldier<br />

in <strong>Moses</strong>’ army, but his marginal mention reinforces<br />

<strong>the</strong> mythic proportion of <strong>Moses</strong>’ genius, at <strong>the</strong> cost of portraying<br />

more clearly <strong>the</strong> history <strong>and</strong> agency behind earlier roads<br />

<strong>and</strong> environmental reform projects like <strong>the</strong> Bronx River Parkway.<br />

For generations before <strong>Moses</strong>, <strong>the</strong> broad idea that public<br />

infrastructure projects should be catalysts for urban improvement<br />

<strong>and</strong> metropolitan transformation was ingrained in New<br />

York’s history. Consider <strong>the</strong> Croton Aqueduct, <strong>the</strong> planning<br />

of new streets <strong>and</strong> avenues, or <strong>the</strong> building of Central <strong>and</strong><br />

Prospect parks. The idea that great public spending on vast<br />

public works would prompt economic growth, guide geographical<br />

expansion, create civic identity, <strong>and</strong> perform social engineering<br />

reached <strong>the</strong>ir apex in <strong>the</strong> Progressive visions of <strong>the</strong><br />

early twentieth century—reforms partly realized when <strong>Moses</strong><br />

was learning at <strong>the</strong> foot of an older generation of reformers<br />

early in his career, working at <strong>the</strong> good-government Bureau of<br />

Municipal Research.<br />

Public Service<br />

<strong>Moses</strong>’ empire came crashing down amid <strong>the</strong> shifting politics<br />

of locality, community, <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r special interests in <strong>the</strong> 1950s<br />

<strong>and</strong> 1960s. And while <strong>the</strong> exhibits underemphasize <strong>Moses</strong>’<br />

history, <strong>the</strong> whole project performs a great public service,<br />

<strong>and</strong> begs similar retrospectives devoted <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r agents<br />

of change in New York, or American cities more generally: of<br />

mayors or community groups, of mavericks like Jane Jacobs<br />

<strong>and</strong> her colleagues, who helped turn <strong>the</strong> tide in Washington<br />

Square Park. Not that <strong>the</strong>se agents could rival <strong>the</strong> giant <strong>Moses</strong><br />

(or photograph as well), but such exhibit-book projects could<br />

round out our picture of urban history in leaps equal to this<br />

year’s <strong>Moses</strong> extravaganza.<br />

Toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> exhibits <strong>and</strong> catalogue capture his<br />

career <strong>and</strong> impact well, giving practitioners, officials, observers,<br />

71

<strong>and</strong> students today much to reflect on. But to <strong>the</strong> extent that<br />

<strong>Moses</strong> will continue to be understood as an ahistorical character,<br />

he will haunt New York’s memory more than inform it.<br />

R<strong>and</strong>all Mason is an Associate Professor in <strong>the</strong> Graduate Program in Historic<br />

Preservation at <strong>the</strong> University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design. The efforts<br />

of Andrew Haswell Green <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs to build a preservation movement in New<br />

York are detailed in <strong>the</strong> author’s forthcoming Memory Infrastructure: Historic<br />

Preservation in <strong>Modern</strong> New York, 1890-1920.<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 <strong>Robert</strong> A. Caro, The Power Broker: <strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fall of New York (New<br />

York, Knopf, 1974).<br />

2 Hilary Ballon <strong>and</strong> Kenneth T. Jackson, eds. <strong>Robert</strong> <strong>Moses</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>City</strong>: The<br />

Transformation of New York (New York,W.W. Norton <strong>and</strong> Company, 2007), 122.<br />

3 Ibid., 86.<br />

4 Ibid., 70.<br />

72