Sound, Time, & Creativity - S.F.

Sound, Time, & Creativity - S.F.

Sound, Time, & Creativity - S.F.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

62<br />

Rudiments are structured sticking patterns that, when<br />

mastered, help expand a player’s technique, control,<br />

and sound. I was fortunate to spend many hours in lessons<br />

with the legendary jazz drummer Joe Morello. At each meeting,<br />

he assigned me different rudimental sticking patterns<br />

from classic books such as George Lawrence Stone’s Stick<br />

Control, Charley Wilcoxon’s Modern Rudimental Swing<br />

Solos, and Joe’s own Rudimental Jazz, which has recently<br />

been rereleased.<br />

In 1967, when Rudimental Jazz came out, Morello<br />

silenced critics who believed that rudiments weren’t “hip”<br />

or couldn’t swing. In a recent conversation with me, Joe<br />

mentioned that the premise behind the book was to help<br />

students gain an appreciation for applying the basic rudiments<br />

around the drumset. In our lessons, he would<br />

encourage me to think beyond each written example and<br />

come up with new, creative patterns without compromising<br />

the integrity of the rudiment itself, so that’s what we’re<br />

going to explore in this series of articles. Before you dive<br />

into the variations, however, be certain that you have control<br />

of each exercise as originally written. As Joe would<br />

always stress in lessons, you should never sacrifice control<br />

for speed.<br />

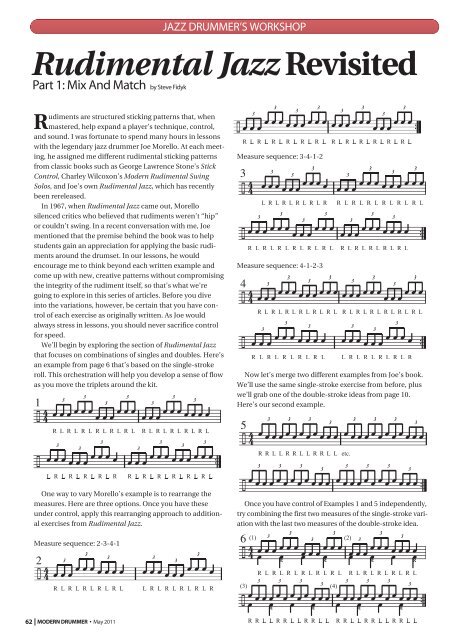

We’ll begin by exploring the section of Rudimental Jazz<br />

that focuses on combinations of singles and doubles. Here’s<br />

an example from page 6 that’s based on the single-stroke<br />

roll. This orchestration will help you develop a sense of flow<br />

as you move the triplets around the kit.<br />

One way to vary Morello’s example is to rearrange the<br />

measures. Here are three options. Once you have these<br />

under control, apply this rearranging approach to additional<br />

exercises from Rudimental Jazz.<br />

Measure sequence: 2-3-4-1<br />

MODERN DRUMMER • May 2011<br />

JAZZ DRUMMER’S WORKSHOP<br />

Rudimental Jazz Revisited<br />

2<br />

Part 1: Mix And Match<br />

1<br />

2<br />

by Steve Fidyk<br />

Measure sequence: 3-4-1-2<br />

3<br />

Measure sequence: 4-1-2-3<br />

4<br />

Now let’s merge two different examples from Joe’s book.<br />

We’ll use the same single-stroke exercise from before, plus<br />

we’ll grab one of the double-stroke ideas from page 10.<br />

Here’s our second example.<br />

5<br />

Once you have control of Examples 1 and 5 independently,<br />

try combining the first two measures of the single-stroke variation<br />

with the last two measures of the double-stroke idea.<br />

6

Now play the first two measures of the double-stroke example<br />

followed by the last two measures of the single-stroke<br />

variation.<br />

7<br />

Next, try practicing the previous merged examples backwards.<br />

Here’s Example 6 in reverse.<br />

8<br />

9<br />

And here’s Example 7 played backwards.<br />

You can continue to mix and match measures and phrases<br />

to come up with a multitude of new musical ideas. Try applying<br />

this concept to the remainder of the original examples in<br />

Rudimental Jazz. In part two of this series, we’ll explore ways<br />

to expand on Joe’s paradiddle variations.<br />

Steve Fidyk is the drummer with the Army Blues Big Band<br />

from Washington, D.C., and a member of the jazz faculty at<br />

Temple University in Philadelphia. Fidyk is also the author<br />

of the critically acclaimed book Inside The Big Band Drum<br />

Chart, which is published by Mel Bay.

THE ORIGINAL STANDARD 26 AMERICAN DRUM RUDIMENTS<br />

1) The Long Roll<br />

2) The Five Stroke Roll<br />

3) The Seven Stroke Roll<br />

4) The Flam<br />

5) The Flam Tap<br />

6) The Flam Accent<br />

7) The Flamacue<br />

8) The Drag or Half Drag<br />

9) The Single Drag - or<br />

Single Drag Tap<br />

10) The Double Drag or<br />

Double Drag Tap<br />

11) The Single Paradiddle<br />

. 12) The Double Paradiddle<br />

13) The Flam Paradiddle Y<br />

14) The Flam Paradiddle-diddle<br />

RL R L R R L<br />

> ><br />

bl<br />

I. I I I<br />

11 ..I I<br />

I u I<br />

LLR LLR L RRL RRL R<br />

R L R R L R L L<br />

> w<br />

R L R L R R L R L R L L<br />

LR L R R R L R L L<br />

n 71 I I I I I I I I<br />

1 1 . - I I I II .I I I I I I<br />

I I<br />

.A<br />

L R L R R L L R L R L L R R

15) The Drag Paradiddle #1<br />

16) The Drag Paradiddle #2<br />

17) The Single Ratamacue<br />

18) The Double Ratamacue<br />

19) The TripleRatamacue<br />

20) The Nine Stroke Roll<br />

21) The Ten Stroke Roll<br />

22) The Eleven Stroke Roll<br />

23) The Thirteen Stroke Roll<br />

24) The Fifteen Stroke Roll<br />

25) Compound Strokes<br />

(Lesson No. 25)<br />

26) The Single - Stroke Roll<br />

R LLR L R R L RRL R L L<br />

-<br />

3 5 3 -<br />

LL R L R L RRL R L R<br />

L R L<br />

R L R<br />

R L R L R L R L etc.<br />

In many musical examples, the above 26 rudiments may be found written with altered accents and rhythms to enhance<br />

the artistry of a particular composer's work; however, the examples will still be drawn from the rudiments above. When<br />

performing isolated rudiments, as in an audition or a contest, it is common practice for the chosen rudiment to be played<br />

from slow to fast to slow using gradual accelerandos and decelerandos.<br />

Example: =-<br />

> > > > ><br />

> ><br />

1 ; ; I I - ; ; r I;;;;;;I<br />

n I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I 1 1 1 I I 1 I I I I I I I I<br />

II I I I<br />

R L R R L R L L R L R R L R L L R L R R L R L L R L R R L R L L<br />

followed by the opposite to bring the rudiment to a close.

<strong>Sound</strong> Enhanced<br />

A play-along audio file that relates to this article can be<br />

found in the Members Only section of the PAS website<br />

at www.pas.org.<br />

Rhythmic Interpretation,<br />

Articulation Markings and<br />

Musical Shape<br />

By Steve Fidyk<br />

The following interpretation is commonly accepted when performing<br />

eighth-note rhythms in a swing style. �is interpretation<br />

gives a smooth, connected, and legato feeling to the swing<br />

rhythms.<br />

�e tempo and style of a composition can also influence the way<br />

eighth notes are interpreted. Early swing music of the 1920s and ’30s, for<br />

example, has a phrasing that is more closely related to this interpretation:<br />

With arrangements played in a fast bebop style (300 bpm or faster),<br />

the eighth notes are interpreted and performed fairly straight:<br />

No set rules govern the way a particular phrase is to be swung. Each<br />

band has its own rhythmic feel and phrasing style. To recognize this,<br />

listen to the lead players (trumpet 1, trombone 1, and alto 1) and match<br />

their phrasing and accents.<br />

ARTICULATION MARKINGS<br />

As drummers, we cannot play note durations with the accuracy of<br />

a horn player, but we can designate sound sources from the drumset<br />

that best complement the articulation and intensity of a note or phrase.<br />

Often, drummers base their approach to articulation on the duration<br />

or length of a note. �is method promotes that all short notes are to be<br />

played on high sounds like the snare drum, and long notes are voiced on<br />

low sounds like the floor tom or bass drum.<br />

PERCUSSIVE NOTES 30 APRIL 2009<br />

�e following articulation symbols are common in horn parts. �ey<br />

are used as indicators for emphasis.<br />

�is symbol (-) signifies a long attack<br />

(.) or (^) suggests a short attack<br />

An accent (>) can be interpreted long or short, depending upon the<br />

style and context.<br />

A note’s articulation is determined in part by: what section of the<br />

band is playing; the intensity of the phrase; the instrument range (high<br />

or low) in which the phrase is played.<br />

�e key is to listen and allow your ears and musical instincts to point<br />

you in the right direction. Your approach to phrasing and articulating<br />

should always complement the ensemble, and by reading and understanding<br />

these symbols and their meanings, you will bring clarity to the<br />

longer phrases you play.<br />

Below is an example showing a trumpet 1 phrase with articulation<br />

marks.<br />

If we expose the rhythms with articulations, we have a phrase that<br />

illustrates the emphasized horn rhythms. �ese are destination points in<br />

a musical line that create a second tier of accent texture. With just the<br />

articulated rhythm, the phrase looks like this:

Here is a common drumset articulation for this phrase.<br />

By reading and emphasizing the articulated rhythm, you naturally<br />

attain the notes a horn player would give significance to. Now you are<br />

phrasing and articulating with the band!<br />

DYNAMIC EXPRESSION AND MUSICAL SHAPE<br />

Each note we play has a dynamic. Percussionists achieve dynamic<br />

diversity through their stroke, motion, and stick direction. �e closer<br />

the sticks are to the instrument when we begin our stroke, the softer the<br />

attack will be. Conversely, a stroke begun further away from the drum<br />

produces a louder dynamic.<br />

�e speed or velocity at which we throw the stick to the instrument<br />

can also influence the way a phrase is felt and heard. A faster stick<br />

velocity can produce rhythms with more intensity and forward<br />

momentum. As you practice, try varying your stick height and velocity<br />

and listen carefully to the differences in dynamic inflection. �is<br />

approach can help bring expression to the written notation.<br />

Music of all styles or genres has shape. As a piece of music develops,<br />

phrases ascend with intensity or descend, creating different musical<br />

textures and moods. As you read, you will notice that drum parts from<br />

big band arrangements have a multitude of single “flat line” rhythms that<br />

do not indicate shape.<br />

Below is an example of a typical band figure from a drum part. Does<br />

the musical line ascend or descend? It’s impossible to tell by observing<br />

the drum part alone.<br />

Flat line drumset section figure<br />

Below are the same two measures from the trumpet one part:<br />

�e line drawing below approximates the shape of the above multiple-note<br />

trumpet figure. You can try this by drawing an imaginary line<br />

through each note head in a phrase and mirror the shape on the drums<br />

and cymbals.<br />

Musical examples from Inside the Big Band Drum Chart by Steve Fidyk<br />

Copyright © 2008 Mel Bay Publications, Inc.<br />

All rights reserved. Used with Permission.<br />

Steve Fidyk is a jazz drummer, author, and educator who has toured<br />

and recorded with Maureen McGovern, New York Voices, Cathy Fink<br />

and Marcy Marxer, �e Capitol Bones, and �e Taylor/Fidyk Big Band.<br />

He is currently the drummer with the Army Blues Jazz Ensemble from<br />

Washington D.C. Fidyk has authored �e Drum Set SMART Book, Inside<br />

the Big Band Drum Chart, Jazz Drum Set Independence 3/4, 4/4, and 5/4<br />

<strong>Time</strong> Signatures, and an instructional DVD, Set Up and Play!, all published<br />

by Mel Bay. He has also recorded over 75 jazz play-along volumes<br />

for the Hal Leonard Corporation. Fidyk is a member of the jazz faculty<br />

at Temple University in Philadelphia. PN<br />

PERCUSSIVE NOTES 31 APRIL 2009

In order to evolve as musicians, it is essential to digest concepts<br />

and techniques of the great drummers. Transcribing,<br />

analyzing, listening to recordings, attending live performance,<br />

and practicing transcriptions can help increase your understanding<br />

of a particular player’s style in greater depth.<br />

But when it comes to adapting the vocabulary developed by<br />

the great jazz drummers into your own style, you don’t want to<br />

just repeat their licks and phrases verbatim. To become truly<br />

fluent in the jazz drumming language, you must be able to mix<br />

and match the rhythms and techniques so that you can ultimately<br />

make your own statements.<br />

Transcribed examples provide a wealth of material from<br />

which to learn musical phrases. Doing your own transcribing<br />

can help you understand how and why these phrases were<br />

played. But whether you are working from transcriptions you<br />

have done yourself or transcriptions that have been published<br />

elsewhere, playing the transcription as written is just the first<br />

step.<br />

Here are three four-measure solo examples rooted in the<br />

bebop tradition.<br />

/<br />

PERCUSSIVE NOTES 20 FEBRUARY 2000<br />

Learning the Jazz Drumming<br />

Language Through Transcriptions<br />

BY STEVE FIDYK<br />

¿ œ œ œ ¿ œ ¿<br />

hi-hat bass drum large tom snare stick shot small tom ride cym.<br />

œ œ<br />

=<br />

3<br />

œ ‰ œ<br />

PERCUSSIVE NOTES<br />

ADVERTISING DEADLINES<br />

ISSUE SPACE FILM/ ART<br />

April Jan. 26 Feb. 9<br />

June Mar. 29 Apr. 12<br />

August May 31 June 14<br />

October June 26 Aug. 9<br />

December Sept. 27 Oct. 11<br />

For More Information Call (580) 353-1455<br />

e-mail: percarts@pas.org<br />

/4 4<br />

1<br />

/<br />

/4 4<br />

2<br />

/<br />

/4 4<br />

3<br />

¿ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ¿ œ œ œ ‰ œ ><br />

3 3 3 3 ><br />

œ œ œœ<br />

œ œœ<br />

œ œœ<br />

œ œ<br />

¿<br />

œ ‰ ¿ ‰ j > 3<br />

œ œ œ œ œ > œ<br />

3<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

œ ‰ œ ><br />

/ œ œ<br />

> 3<br />

3 > 3 3<br />

œœ œ<br />

œ<br />

œ œœ<br />

œ ¿ œ<br />

œ œ œ<br />

‰ j<br />

œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ > œ > œ<br />

3<br />

¿ ¿ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ ><br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

œ œ ‰ œ œ œ ‰ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ¿<br />

3<br />

œ œ ‰ œ œ ‰ œ<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

œ œ<br />

œ œ<br />

œ œ<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

1. First, practice each example on a single plane (e.g., a drum<br />

pad or snare drum) to ensure accuracy of note values.<br />

2. Play each four-measure example as written, adding the following<br />

hi-hat ostinatos.<br />

A<br />

/4<br />

4 Œ<br />

¿<br />

Œ<br />

¿<br />

3. Now, try juxtaposing each example by starting the fourmeasure<br />

phrase on beat one of measures two, three, and four.<br />

For example, this is the way four-bar phrase number 2 looks<br />

when it starts on beat one of measure two.<br />

B<br />

¿ ¿ ¿ ¿

4 4 œ > œ<br />

/ ‰ j<br />

œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ > œ > œ<br />

3<br />

¿ ¿ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3 > 3<br />

œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ œ<br />

œ ‰ œ ><br />

3<br />

œ œ<br />

œ<br />

¿<br />

œ ‰ ¿ ‰ j > 3<br />

œ<br />

œ œ œ<br />

Shifting the departure point makes the four-measure phrase<br />

sound and feel completely different. Each example has a total of<br />

sixteen departure points to choose from: four beats per measure<br />

times four measures equals sixteen points. This “circular fours”<br />

approach allows you to come up with new solo phrases based on<br />

the original example.<br />

Now try playing four-bar phrase number 2 starting on beat<br />

one of measure three, and then start on beat one of measure<br />

four. Then incorporate the hi-hat ostinatos.<br />

The next step is to combine examples. Here is four-bar<br />

phrase number 1, measures one and two, combined with fourbar<br />

phrase number 3, measures three and four.<br />

/4 4 ¿ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ¿ œ œ œ ‰ œ ><br />

/ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ ‰ œ œ ‰ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

You can expand each note value within the four-measure<br />

phrase. For example, written quarter notes would become half<br />

notes; eighth notes would become quarter notes; eighth-note<br />

triplets would become quarter-note triplets. By expanding each<br />

note value, the four-measure phrase becomes an eight-measure<br />

phrase. Here is four-bar phrase number 3 after being expanded.<br />

/4 4 œ œ Œ œ œ œ Œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙<br />

3<br />

/ œ œ<br />

œ œ Œ œ œ Œ œ<br />

3 3<br />

œ œ<br />

œ œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

3<br />

œ œ œ<br />

In addition to expanding the phrase, you can also compress<br />

the phrase. Quarter notes become eighth notes, eighth notes become<br />

sixteenths, and so on. Compressing each note value converts<br />

a four-measure phrase into a two-measure phrase. Here is<br />

four-bar phrase number 1 after being compressed.<br />

/4 4 ¿ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ¿ œ œ œ ≈ œ ><br />

/<br />

6<br />

œ œ œ œ œœ<br />

6<br />

6<br />

><br />

œ œ œ œ œ œœ<br />

œ œ<br />

œ ><br />

6<br />

œ œ œœ ¿ ><br />

œ<br />

œ œ œ<br />

PERCUSSIVE NOTES 21 FEBRUARY 2000

PERCUSSIVE NOTES 22 FEBRUARY 2000<br />

The combination possibilities are endless. Mix them up and<br />

have fun. Do not limit your practicing of transcriptions to one<br />

style of music. Try combining transcriptions from different<br />

drummers or idioms to come up with a unique style: your own!<br />

Approaching transcriptions from this angle serves as a tool to<br />

develop a better sense of phrasing. It will also improve your<br />

reading skills and stimulate creativity. In essence, you are using<br />

a particular drummer’s ideas (based on the transcription<br />

with its modifications) to orchestrate your own style.<br />

Steve Fidyk has performed and/or recorded<br />

with such artists as Mark Taylor, New York<br />

Voices, Arturo Sandoval, Clark Terry, The<br />

Capital Bones, and Chris Vadala. He is the<br />

drummer and featured soloist with the<br />

Army Blues Jazz Ensemble of Washington<br />

D.C., Director of Drumset Studies at the<br />

University of Maryland, College Park, and<br />

he contributed transcriptions to Peter<br />

Erskine’s book The Drum Perspective, published by Hal<br />

Leonard. His solo CD, Big Kids, is available at<br />

www.stevefidyk.com. PN

Wire Brush Technique<br />

Practicing brushes is excellent for developing strength in your wrist and fingers. It can<br />

help develop the muscles and reflexes and also improve your control with sticks. With<br />

the exception of the closed roll, any pattern that is played with sticks can be executed<br />

with brushes. Of course, you don’t have the advantage of a natural rebound with brushes<br />

as you do with a stick. Nevertheless, you can develop a clear, crisp tone with brushes and<br />

play with surprising volume when using a proper technique.<br />

A brush can produce staccato and legato sounds…<br />

For a staccato sound, snap the brush downward to the head and draw the sound from the<br />

drum by striking and lifting the fan immediately.<br />

For a “slappy” staccato sound, press the fan into the drum head.<br />

For a legato approach, sweep the fan across the head in a circular motion producing a<br />

“swish” sound. The brush fan pivots across the head with a flowing motion controlled by<br />

the fingers, forearm, and wrist.<br />

Right Hand Hold<br />

The right brush is controlled with a combination<br />

of wrist and fingers with all four fingers<br />

remaining on the handle. To produce a sound,<br />

you must lift the fan off the head since a brush<br />

will not rebound like a stick.

For the left hand, the index and middle fingers are positioned on top of the brush handle<br />

as the ring finger acts as a bumper underneath. The fingers stay in constant contact with<br />

the handle at all times.<br />

Left Hand with fingers in the open position (beats 1 and 3)<br />

Left Hand with fingers in the closed position (beats 2 and 4)<br />

The open and closed positions in the previous photographs refer to the movement of the<br />

fingers when performing legato sweeps on the drum head.

Practice this finger movement playing legato quarter notes in 4/4 time with your left<br />

hand. Beats one and three utilize the open position, beats two and four (closed position),<br />

close your fingers into your palm.<br />

The most common jazz beat diagram with brushes is notated below. Notice that the right<br />

hand plays the jazz ride pattern on the opposite side of the drum staying out of the way of<br />

the left hand legato swish. The left hand rotates around the drum in a clockwise motion<br />

keeping a smooth and connected pulse with its movement.<br />

Spending time practicing brush beats with recordings can help you feel confident as you<br />

begin creating beats that swing and sound balanced hand to hand. My overall brush<br />

concept is based on moves that my teacher Joe Morello showed me. I also listen to<br />

drummers Jeff Hamilton, Ed Thigpen, Shelly Manne and Philly Joe Jones and try to<br />

emulate the sound and feel they produce.<br />

Below are several brush patterns for practice in varying styles with tempo ranges for each<br />

diagram. Please refer to the DVD to view a performance of each brush diagram notated<br />

below. For information on these brush maps, please visit www.prologixpercussion.com

The legato shuffle uses the sweeping technique with both brushes producing a connected<br />

swish sound.<br />

As you practice this beat, concentrate on keeping the sound of each sweep rhythm<br />

consistent.

The fast swing brush beat combines two sounds: The staccato tap in the right hand with<br />

the left hand swish technique.<br />

Since this beat is played at tempos of 300 beats per minute or faster, relax and breathe...<br />

Also, focus on blending the staccato tap sound with the left swish brush pattern so the<br />

beat sounds complete hand to hand.<br />

With the quarter note sweep beat, the left hand creates a sweep accent on the “a” of beats<br />

1 and 3 by closing the fingers into the palm of the left hand.<br />

As you practice combining both hands, notice that the composite rhythm is a shuffle.

Meet me in the middle is a beat that is similar to a pattern I’ve seen the legendary Joe<br />

Morello play. You can hear this groove on many classic recordings he did with the Dave<br />

Brubeck Quartet from the 1950’s and 60’s.<br />

As you practice, focus on coordinating the left hand sweep accent on the “a” of 2 and 4 in<br />

perfect unison with the right hand swing beat.

With this ¾ brush beat, the left hand creates a sweep accent on the “a” of beats 1 and 3 by<br />

closing the fingers into the palm of the left hand.<br />

As you practice this walking ballad beat, concentrate on the right hand as it sweeps, lifts,<br />

and taps. Subdivide each eighth note as you coordinate both hands.

The samba brush beat features the Brazilian ground rhythm in the left hand. As you<br />

sweep, your fingers close into the palm of your hand for each note value within this two<br />

measure pattern. The dot located on the left hand diagram is the point where the brush fan<br />

crosses the head as it accents the samba rhythm.<br />

Once you have control and confidence with the above patterns, experiment and create<br />

some of your own by incorporating the sweep, slap, and snap sounds. You can also create<br />

additional sound effects using the following approaches.

The Trill<br />

Handle Flex<br />

To produce a trill, pivot the fan left to<br />

right with your middle, ring, and pinky<br />

fingers.<br />

Holding the brush firmly,<br />

press the handle against the<br />

rim. This will flex the brush<br />

fan creating multiple strokes<br />

with one downward motion.

Handle Roll<br />

A roll effect is created<br />

with the fan when you<br />

turn the handle on the<br />

rim controlled by your<br />

palm.