Chapter 9 - Pearson

Chapter 9 - Pearson

Chapter 9 - Pearson

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CHAPTER 9<br />

Exoticism<br />

1830s–1920s<br />

Inspired by revivalism, eclecticism, and a quest for novelty<br />

in the second half of the 19th century, Exoticism<br />

looks to non-Western cultures for inspiration and borrows<br />

their forms, colors, and motifs. International expositions,<br />

books, periodicals, travel, and advances in<br />

technology acquaint Europeans and Americans with<br />

other cultures while creating a romantic image of faraway<br />

lands and people. Egyptian Revival, Moorish or<br />

Islamic, Turkish, and Indian join, yet never completely<br />

surpass other fashionable styles.<br />

HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL<br />

By the middle of the 19th century, Europeans and Americans<br />

(Fig. 9-1) begin to lose interest in the prevailing<br />

styles, such as Greek Revival and Gothic Revival. Their<br />

desire for new and novel styles opens the door for exotic<br />

influences. At the same time, designers are looking for new<br />

sources of inspiration apart from the rampant historicism.<br />

Eclecticism, a dominant force in design during the time,<br />

encourages the exploration and appreciation of the architecture<br />

and decorative arts of other cultures. Although<br />

exotic-style public and private buildings, interiors, and<br />

212<br />

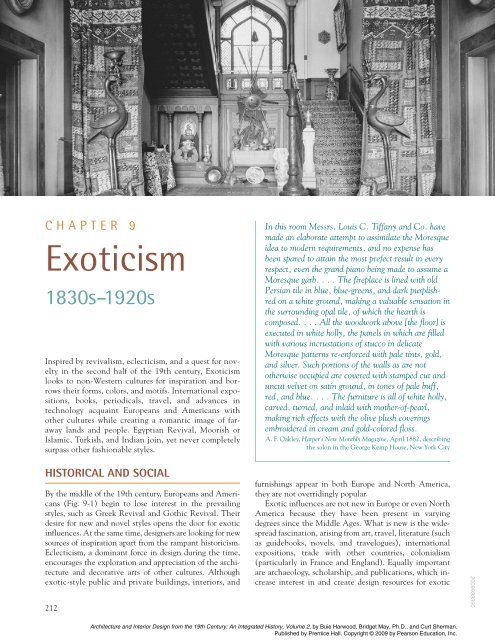

In this room Messrs. Louis C. Tiffany and Co. have<br />

made an elaborate attempt to assimilate the Moresque<br />

idea to modern requirements, and no expense has<br />

been spared to attain the most prefect result in every<br />

respect, even the grand piano being made to assume a<br />

Moresque garb. . . . The fireplace is lined with old<br />

Persian tile in blue, blue-greens, and dark purplishred<br />

on a white ground, making a valuable sensation in<br />

the surrounding opal tile, of which the hearth is<br />

composed. . . . All the woodwork above [the floor] is<br />

executed in white holly, the panels in which are filled<br />

with various incrustations of stucco in delicate<br />

Moresque patterns re-enforced with pale tints, gold,<br />

and silver. Such portions of the walls as are not<br />

otherwise occupied are covered with stamped cut and<br />

uncut velvet on satin ground, in tones of pale buff,<br />

red, and blue. . . . The furniture is all of white holly,<br />

carved, turned, and inlaid with mother-of-pearl,<br />

making rich effects with the olive plush coverings<br />

embroidered in cream and gold-colored floss.<br />

A. F. Oakley, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, April 1882, describing<br />

the salon in the George Kemp House, New York City<br />

furnishings appear in both Europe and North America,<br />

they are not overridingly popular.<br />

Exotic influences are not new in Europe or even North<br />

America because they have been present in varying<br />

degrees since the Middle Ages. What is new is the widespread<br />

fascination, arising from art, travel, literature (such<br />

as guidebooks, novels, and travelogues), international<br />

expositions, trade with other countries, colonialism<br />

(particularly in France and England). Equally important<br />

are archaeology, scholarship, and publications, which increase<br />

interest in and create design resources for exotic<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

cultures. This intense scrutiny engenders myths about<br />

the lives, people, customs, architecture, and objects in<br />

other countries. Exotic styles arise mainly from the Egyptian<br />

and Islamic cultures, which have centuries of artistic traditions<br />

that are largely unknown to Westerners until the<br />

19th century.<br />

■ Egyptian Revival. The art and architecture of ancient<br />

Egypt project a timeless, formal, and ordered appearance<br />

arising from a hierarchal society immersed in religion. The<br />

most significant structures—pyramids, tombs, and temples—<br />

are associated with spirituality, death, and rebirth. Noteworthy<br />

introductions include the column, capital, pylon,<br />

and obelisk. Egyptians are known for achievements in<br />

medicine, astronomy, and geometry.<br />

Characteristics of Egyptian architecture appear in and<br />

influence art and architecture as early as classical antiquity<br />

and continue in varying degrees through the Renaissance,<br />

the Baroque, and into the 18th century. In the middle of<br />

the 18th century, some interest in Egypt arises following<br />

Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s creation and publication of<br />

Egyptian style interiors in the Caffeè degli Inglese (English<br />

Coffee House) in Rome and his prints of Egyptian style<br />

details. At the same time, Neoclassical architects, influenced<br />

by French theories, adopt the forms, geometric volumes,<br />

and some details of Egyptian architecture to express<br />

clarity, severity, and integrity. Subsequent interest in<br />

Egyptian art and architecture usually corresponds to events<br />

that bring attention to it.<br />

The earliest widespread adoption of Egyptian forms and<br />

motifs in architecture and the decorative arts begins following<br />

Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798–1799.<br />

Napoleon’s scientists, cartographers, engineers, and artists<br />

study and record tombs, temples, and other buildings, and<br />

the newly established Insitut d’Egypte examines all aspects<br />

of Egyptian civilization. These sources provide a wealth of<br />

information about Egypt, ancient and modern, and acquaint<br />

people with the land, about which little is known in<br />

the West. A few Egyptian-style buildings and interiors<br />

occur, and Egyptian details are applied to furniture.<br />

A larger Egyptian Revival begins at midcentury aided<br />

by new technology, which makes emulation of ancient<br />

artifacts easier, faster, and more practical. Knowledge of<br />

Egyptian and other cultures increases through developments<br />

in communications that make the world seem<br />

smaller and allow almost anyone to visit faraway lands<br />

through photographs and stereo views. Museums and<br />

individuals collect and exhibit artifacts unearthed in<br />

numerous archaeological sites, further acquainting and<br />

stirring more interest. The successful Egyptian Court at<br />

the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 leads to similar displays<br />

at later expositions. Egypt even finds a place in the<br />

design reform movements of the mid-19th century as the<br />

adherents admire the stylized forms of its ornament and<br />

sturdy and honest construction of its furniture.<br />

EXOTICISM 213<br />

A new wave of Egyptian Revival begins in the 1870s,<br />

inspired by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Giuseppe<br />

Verdi’s opera Aida of 1871 with its colorful Egyptian-style<br />

sets, and the installation of Egyptian obelisks in London in<br />

1878 and New York’s Central Park in 1879. The revival continues<br />

until the end of the 19th century when interest begins<br />

to wane, although use of Egyptian forms and motifs never<br />

completely ceases. In 1922, the discovery of the tomb of<br />

Tutankhamen immediately stirs renewed interest in and<br />

emulation of ancient Egypt.<br />

■ Turkish, Arab, Saracenic, or Moorish and Indian Styles.<br />

Like Egypt, religion is a significant influence on Islamic<br />

art and architecture. The design traditions of its various<br />

peoples and the aesthetic sensibilities of its artists and<br />

builders contribute to its unique form and decoration.<br />

Common to all arts are dense, flat patterns composed of<br />

geometric forms and curving tendrils, which dematerialize<br />

form and create visual complexity. Also unique is calligraphy<br />

that is integrated into decoration of nearly all objects<br />

and structures.<br />

Europeans are somewhat acquainted with Turkey, Persia,<br />

Syria, Morocco, Moorish Spain, and India before the<br />

mid-19th century. In the 1830s, a religious revival in<br />

England focuses attention on Palestine where Christ had<br />

lived. Painters, artists, and architects go to the Middle<br />

East to study, paint, and sketch. Upon their return, many<br />

publish their work. Design reformers admire the intricate,<br />

stylized, and colorful designs and motifs of the<br />

Middle East and promote them in their work and publications.<br />

Panoramas, a popular form of entertainment;<br />

photographs; travel books; and stereo views depict<br />

Cairo, Jerusalem, Paestum, Karnak, and Pompeii along<br />

with other exotic sights.<br />

� 9-1. Woman’s costume showing<br />

paisley underskirt; published in<br />

Bloomingdale’s catalog, 1886.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

214 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

Like Egyptian Revival, expositions acquaint people<br />

with the Islamic art and decoration. The Alhambra Court<br />

at the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 is also very successful<br />

as is a smaller version in the New Crystal Palace<br />

four years later in London. Both are important models for<br />

designers. At the Centennial International Exposition of<br />

1876 in Philadelphia, several buildings are Islamic in form<br />

if not visual character. Turkish bazaars, cafés, and entertainment<br />

pavilions at successive expositions provide places<br />

for shopping, eating, and amusement. Not to be outdone,<br />

department stores and warehouses, such as Macy’s in New<br />

York and Liberty’s in London, import goods from the Middle<br />

East and display them in bazaars or use them in tearooms<br />

throughout the 1870s and 1880s. This inspires a<br />

domestic craze for Turkish or Cozy corners.<br />

Closely aligned with the Turkish, Moorish, Saracenic<br />

or Arab (as it is called) in Britain is the Indian or Mogul<br />

style, a Victorian interpretation of Indian art and life. The<br />

English colonists and military returning home bring ideas,<br />

architecture, and objects from India, an important British<br />

possession. India also exports many goods to the mother<br />

country. Displays of Indian wares are well attended at the<br />

Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851. The style is limited to<br />

a few examples in Great Britain.<br />

CONCEPTS<br />

Fascination with non-Western cultures gives rise to Egyptian<br />

Revival, Turkish or Islamic styles, and the Indian or<br />

Mogul style with various intensities throughout the 19th<br />

century and into the 20th. Common among them is the<br />

adaptation of characteristics of the cultures to Western<br />

tastes and needs. By the mid-19th century, associations and<br />

symbolism strongly influence stylistic choices and the visual<br />

image. Each style is associated with particular building<br />

IMPORTANT TREATISES<br />

■ L’art arabe d’après les monuments du Caire,<br />

1869; Emile Prisse d’Avennes.<br />

■ Atlas de l’histoire de l’art égyptien, 1870; Emile<br />

Prisse d’Avennes.<br />

■ Domestic Architecture, 1841; Richard Brown.<br />

■ Grammar of Ornament, 1856; Owen Jones.<br />

■ Manners and Customs of the Ancient<br />

Egyptians, 1837; John Gardner Wilkinson.<br />

■ Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the<br />

Alhambra, 1824–1825; Owen Jones.<br />

■ Voyage dans la basse et la haute égypte,<br />

1802; Baron de Denon.<br />

types, rooms, and furniture, and conveys a particular<br />

image, such as timelessness, monumentality, or a touch of<br />

the exotic in an otherwise ordinary Victorian house.<br />

DESIGN CHARACTERISTICS<br />

Non-Western cultures during the 19th and early 20th<br />

centuries inspire several Exotic revivals, including<br />

Egyptian Revival and Turkish or Moorish Revival. Each<br />

is an assemblage of motifs applied to contemporary<br />

forms. Few, if any, attempts are made to live as other cultures<br />

do because associations and evoking an image are<br />

more important. The forms and motifs of the culture<br />

define the style.<br />

■ Egyptian Revival. Although Egyptian forms and motifs<br />

appear in architecture beginning in antiquity, the first<br />

conscious revival occurs about 1810. Egyptian Revival<br />

architecture adopts the monumentality, simplicity, column<br />

forms, battered sides, and other architectural details<br />

and motifs of the surviving buildings of ancient Egypt.<br />

The small number of examples is limited to a few buildings<br />

types. Interiors, furniture, and decorative arts adopt<br />

the details and motifs more than the forms of Egyptian<br />

architecture. Eclecticism is characteristic in interiors<br />

and furniture. Most often, Egyptian details are applied to<br />

contemporary forms, but in the second half of the 19th<br />

century, Egyptian chairs and stools are copied.<br />

■ Turkish, Arab, Saracenic, Moorish, and Indian Styles.<br />

Often evident in these styles are the architectural details<br />

and complex layered ornament of Islamic art and architecture.<br />

European and American designers sometimes strive<br />

to use forms and motifs more correctly, although still copying<br />

and reinterpreting them. Access to more information<br />

enables them to develop greater archaeological correctness.<br />

In architecture, fully Turkish or Moorish expressions<br />

are extremely rare, but many buildings display some architectural<br />

details. Similarly, interiors also have Moorish<br />

architectural details combined with other styles. Mostly<br />

limited to particular types, such as smoking rooms, interiors<br />

may be filled with rugs, furniture, and decorative arts<br />

from the Middle East as well as Western interpretations.<br />

Overstuffed, deeply tufted upholstery is the most common<br />

example of Turkish-style furniture.<br />

■ Motifs. Characteristic motifs are geometric forms typical<br />

of Egyptian architecture, columns and other architectural<br />

details, as well as real and fake hieroglyphs,<br />

scarabs, Egyptian figures or heads, Egyptian gods and<br />

goddesses, lotus, papyrus, crocodiles, cobra, sphinxes,<br />

and sun disk (Fig. 9-2, 9-4, 9-5, 9-6, 9-7, 9-19, 9-23,<br />

9-24, 9-41). Islamic or Turkish motifs include onion<br />

domes, minarets, lattice, horseshoe arches, multifoil arches,<br />

ogee arches, peacocks, carnations, vases, arabesques, and<br />

flat and intricate patterns (Fig. 9-2, 9-3, 9-13, 9-17, 9-20,<br />

9-25, 9-34).<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

� 9-2. Turkish, Persian, Indian, and Egyptian designs published in The Grammar of Ornament, 1856, by Owen Jones.<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

Examples of Exoticism in architecture are uncommon<br />

when compared to other styles. Rare in residences, designers<br />

apply exotic styles to particular public building types. In<br />

the 19th century, the idea that a building’s design should<br />

convey its purpose governs stylistic choices, making certain<br />

styles appropriate for particular types of buildings.<br />

Symbolism, acknowledged through form and motifs, is an<br />

important design context and characteristic. Thus, the<br />

ancient Egyptians’ strong belief in life after death makes<br />

their art and architecture appropriate for cemeteries and<br />

EXOTICISM 215<br />

funerary buildings. Themes of justice, solidity, and security<br />

give rise to Egyptian Revival courthouses and prisons. The<br />

perceived superior knowledge of the ancient Egyptians<br />

deems the style appropriate for libraries and centers of<br />

learning. Medical buildings often feature the style because<br />

of the 19th century’s belief in Egypt’s advanced medical<br />

knowledge and practices. Freemasons, secret societies, and<br />

fraternal lodges see Egypt’s mysterious image and wisdom as<br />

ample reason for choosing its style. For bridges and train<br />

stations, Egyptian Revival symbolizes advancements in<br />

technology. Less obvious is the choice of Egyptian Revival<br />

for churches and synagogues.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

216 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-3. Porch, wall elevation, and door detail, mid-19th century. Islamic influence.<br />

� 9-4. Philadelphia County Prison, Debtors’ Wing, 1836; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Thomas U. Walter. Egyptian Revival.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

IMPORTANT BUILDINGS AND INTERIORS<br />

■ Antwerp, Belgium:<br />

—Elephant Pavilion, Antwerp Zoo, 1855–1856;<br />

Charles Servais. Egyptian Revival.<br />

■ Atlanta, Georgia:<br />

—Yaarab Temple Shrine Mosque (Fox Theater),<br />

1927–1929; Marye, Alger, and Vinour. Islamic<br />

Revival.<br />

■ Boise, Idaho:<br />

—Ada Theater, 1926; Frederick C. Hummel.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

■ Cincinnati, Ohio:<br />

—Isaac M. Wise Temple, 1866; James K. Wilson.<br />

Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

■ Devonport, England:<br />

—Egyptian Library, 1823; John Foulston. Egyptian<br />

Revival.<br />

■ Glasgow, Scotland:<br />

—Templeton’s Carpet Factory, 1889–1892.<br />

Exotic/Byzantine Revival.<br />

■ Hudson, New York:<br />

—Olana, 1870–1872 house, 1888–1891 studio<br />

wing; Frederic E. Church, consulting architect<br />

Calvert Vaux. Exotic/Moorish Revival.<br />

■ Leeds, England:<br />

—Temple Mill, 1842; Joseph Bonomi, Jr. Egyptian<br />

Revival.<br />

■ London, England:<br />

—Arab Hall, Lord Leighton House, c. 1865; George<br />

Aitchison. Exotic/Islamic Revival.<br />

—The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, 1812; P. F.<br />

Robinson. Egyptian Revival.<br />

■ Los Angeles, California:<br />

—Egyptian Theater, 1922; Meyer and Holler.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

—Los Angeles Public Library, 1922–1926; Bertram<br />

G. Goodhue and Carlton M. Winslow.<br />

Egyptian/Islamic Revival.<br />

—Sampson Tyre and Rubber Company Building,<br />

1929; Morgan, Walls, and Clements. Exotic.<br />

■ Mitchell, South Dakota:<br />

—Corn Palace, 1921; Rapp and Rapp.<br />

Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

■ Nashville, Tennessee:<br />

—First Presbyterian Church, 1848–1851; William<br />

Strickland. Egyptian Revival.<br />

EXOTICISM 217<br />

■ New Haven, Connecticut:<br />

—Grove Street Cemetery Entrance, 1845; Henry<br />

Austin. Egyptian Revival.<br />

—Willis Bristol House, 1846; Henry Austin.<br />

Exotic/Islamic Revival.<br />

■ New York City, New York:<br />

—New York City Halls of Justice and House of<br />

Detention (The Tombs), 1835–1838; John<br />

Haviland. Egyptian Revival.<br />

■ Paris, France:<br />

—Palais de Justice, 1857–1868; Joseph-Louis Duc.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

■ Philadelphia, Pennsylvania:<br />

—Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1871–1876;<br />

Frank Furness and George W. Hewitt. Exotic<br />

Revival.<br />

—Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Company, c. 1839,<br />

John Haviland, and 1902, Theophilus Parsons<br />

Chandler, Jr. Egyptian Revival.<br />

—Philadelphia County Prison, Debtors’<br />

Wing, 1836; Thomas U. Walter. Egyptian<br />

Revival.<br />

■ Richmond, Virginia:<br />

—Egyptian Building, Medical College of Virginia<br />

(now a part of Virginia Commonwealth<br />

University), 1844–1845; Thomas S. Stewart.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

—Millhiser House, 1891–1894; William M.<br />

Poindexter. Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

■ Sag Harbor, Long Island, New York:<br />

—First Presbyterian Church, 1843–1844;<br />

to the design of Minard LaFever. Egyptian<br />

Revival.<br />

■ San Francisco, California:<br />

—Fine Arts Building, California Midwinter<br />

International Exposition, 1894. Egyptian<br />

Revival.<br />

—Hindu Society, late 19th century. Turkish/Exotic<br />

Revival.<br />

■ Santa Fe, New Mexico:<br />

—Scottish Rite Cathedral, c. 1912;<br />

C. H. Martindale. Moorish Revival.<br />

■ Washington, D.C.:<br />

—Washington Monument, 1833 (designed),<br />

1848–1884 (built); Robert Mills.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

218 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

DESIGN SPOTLIGHT<br />

Architecture: New York City Halls of Justice and House<br />

of Detention (The Tombs), 1835–1838; New York City,<br />

New York; John Haviland. Egyptian Revival. This building<br />

is one of the most significant Egyptian Revival structures<br />

in the United States. The attributes and visual characteristics<br />

of ancient Egyptian buildings are intended to<br />

convey security, monumentality, terror, and the misery<br />

awaiting those to be incarcerated there. Reminiscent of<br />

the massive gateways at the entrances of Egyptian<br />

tombs, the façade emphasizes symmetry, volume, simple<br />

geometric forms, and minimal ornament. Two wings<br />

� 9-5. New York City Halls of Justice and House of Detention (The Tombs); New York City.<br />

Architects rarely try to re-create authentic Egyptian or<br />

Middle Eastern buildings, preferring instead to apply forms<br />

and motifs to contemporary forms. These details may mix<br />

with other styles. The belief that Egypt influences Greece<br />

prompts Egyptian details in Greek Revival. Islamic patterns<br />

sometimes mix with Gothic Revival in the work of<br />

some designers, such as William Burges, and the Queen<br />

Anne style in the late 19th century.<br />

Never achieving a full revival, Turkish or Moorish details<br />

may define homes and a wide range of public buildings<br />

from the 1860s onward. Picturesque, hedonistic, and erotic<br />

allusions limit the Turkish context for use to those building<br />

types possessing romantic ideals, some tie to the Middle<br />

East, amusement, or entertainment.<br />

Public and Private Buildings<br />

■ Types. Appropriate building types for Egyptian Revival<br />

include cemetery gates and other funerary structures, prisons,<br />

courthouses, commercial buildings, fraternal lodges,<br />

with battered walls and a center entrance portico carried<br />

by Egyptian-style columns compose the facade. Slanted<br />

moldings carrying a lintel form the window surrounds.<br />

A plain or half-circle molding emphasizes the corners<br />

and the cavetto cornice that caps the composition.<br />

Haviland derives the architectural vocabulary from several<br />

scholarly books on ancient Egypt that he owns. The<br />

building also is a model prison for its day, incorporating<br />

fireproofing, natural light and air, sanitary facilities, a<br />

hospital, and individual cells for inmates.<br />

Flat or low pitched roof typical<br />

Cavetto cornice<br />

Cornice or lintel<br />

Plain, rounded molding on corners<br />

Battered or canted plain wall<br />

Egyptian columns define entry and portico<br />

Slanted columns frame windows<br />

Symmetrical composition<br />

and occasionally a church or train station (Fig. 9-4, 9-5,<br />

9-6, 9-7, 9-8, 9-9). In the early 20th century, Egyptian<br />

movie theaters are common (Fig. 9-15). Entire houses in<br />

the Egyptian style are rare, but Egyptian details such as<br />

columns or slanted window surrounds combine with other<br />

styles. Turkish or Moorish defines a variety of building<br />

types, including synagogues, fraternal temples, pubs,<br />

clubs, theaters, music halls, and a few commercial buildings<br />

(Fig. 9-11, 9-12). Moorish-style houses (Fig. 9-17)<br />

are exceedingly eclectic with elements from several styles<br />

applied to contemporary forms.<br />

■ Site Orientation. No particular site orientation is associated<br />

with exotic buildings. Designers do not re-create the<br />

processional entrances to Egyptian temples.<br />

■ Floor Plans. There is no typical Egyptian Revival or<br />

Turkish floor plan. Designers do not re-create accurate<br />

floor plans of any exotic style, but instead develop the plan<br />

from function or an attribute such as symmetry.<br />

■ Materials. Materials include stone, brick, or wood, particularly<br />

in America. Brick may be stuccoed to render the<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

� 9-6. Temple Mill, 1842; Leeds, England; Joseph Bonomi, Jr.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

� 9-7. Egyptian Hall, c. 1840s; Picadilly, London, England.<br />

Egyptian Revival.<br />

EXOTICISM 219<br />

� 9-8. First Presbyterian Church, 1843–1844; Sag Harbor, Long<br />

Island, New York; to the design of Minard LaFever. Egyptian<br />

Revival.<br />

� 9-9. Grove Street Cemetery Entrance, 1845; New Haven,<br />

Connecticut; Henry Austin. Egyptian Revival.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

220 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-10. Egyptian Building, Medical College of Virginia (now a<br />

part of Virginia Commonwealth University), 1844–1845;<br />

Richmond, Virginia; Thomas S. Stewart. Egyptian Revival.<br />

� 9-11. Isaac M. Wise Temple, 1866; Cincinnati, Ohio; James K.<br />

Wilson. Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

smooth walls desirable in Egyptian Revival. Details such as<br />

columns or domes may be in cast iron, terra-cotta, or ceramic<br />

tiles. Turkish or Moorish structures have brightly<br />

colored tiles, details, and intricate patterning composed of<br />

stars, flowers, or arabesques (Fig. 9-17). Common colors include<br />

neutrals, blues, turquoises, greens, purples, oranges,<br />

and reds.<br />

� 9-12. Templeton’s Carpet Factory, 1889–1892; Glasgow,<br />

Scotland. Byzantine and Exotic Revival.<br />

� 9-13. India Building, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893;<br />

Chicago, Illinois; construction by Henry Ives Cobb.<br />

� 9-14. Corn Palace, 1921; Mitchell, South Dakota; Rapp and<br />

Rapp. Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

■ Façades. Façades reveal Egyptian influence through<br />

such visual characteristics as geometric forms, smooth<br />

wall treatments, battered walls, Egyptian reed-bundle or<br />

papyrus columns, cavetto cornices, round moldings, and<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

� 9-15. Yaarab Temple Shrine Mosque (Fox Theater),<br />

1928–1929; Atlanta, Georgia; Marye, Alger, and Vinour. Art<br />

Deco/Egyptian Revival.<br />

� 9-16. Willis Bristol House, 1846; New Haven, Connecticut;<br />

Henry Austin. Exotic/Islamic Revival.<br />

EXOTICISM 221<br />

Egyptian motifs (Fig. 9-4, 9-5, 9-6, 9-7, 9-8, 9-9, 9-10).<br />

Characteristic attributes include massiveness, solemnity,<br />

solidity, and timeless or eternal feeling. The Egyptian gateway<br />

or pylon is a common form for entrances or entire<br />

DESIGN PRACTITIONERS<br />

■ Joseph Bonomi, Jr. (1796–1878) is the curator of<br />

Sir John Soane’s Museum. Bonomi also is a<br />

distinguished Egyptologist who creates many<br />

Egyptian Revival buildings in England. He is best<br />

known for Temple Mills in Leeds and the Egyptian<br />

Court (with Owen Jones) at the New Crystal<br />

Palace in 1854.<br />

■ John Haviland (1792–1852) comes to the United<br />

States from England in 1816. He designs many<br />

Greek Revival buildings as well as the first prison<br />

in the United States to center on reform ideals<br />

from Europe. Haviland is best known for his<br />

Egyptian Revival buildings, including the New<br />

York City Halls of Justice and House of Detention.<br />

He publishes the Builder’s Assistant in 1818,<br />

which is the first American publication to<br />

illustrate the Greek orders.<br />

■ Owen Jones (1809–1874) is a noted designer and<br />

architect, and an authority on color and<br />

ornament. Following extended travels to Spain<br />

and the Middle East, he publishes works that<br />

establish him as an authority on Islamic art and<br />

architecture. As Superintendent of the Works for<br />

the Great Exhibition of 1851, Jones decorates the<br />

interiors of the Crystal Palace. At the new Crystal<br />

Palace, he designs historical interiors in various<br />

styles, including Islamic. His Grammar of<br />

Ornament illustrates ornament in color of<br />

historical styles and works of Islamic, Chinese,<br />

and other non-Western cultures.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

222 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-17. Olana, 1870–1872 house, 1888–1891 studio wing; Hudson, New York; Frederic E. Church, consulting architect Calvert Vaux.<br />

Exotic/Moorish Revival.<br />

� 9-18. Later Interpretation: Luxor Hotel, 1993; Las Vegas,<br />

Nevada; Veldon Simpson. Modern Historicism with Egyptian<br />

influences.<br />

façades. Domes, Moorish arches, minarets, and colorful tiles<br />

define Moorish-style buildings (Fig. 9-11, 9-13, 9-14, 9-15,<br />

9-16, 9-17). Islamic arches may create bays across the<br />

façade and be superimposed on each story.<br />

■ Windows. Windows have slanted sides or surrounds on<br />

Egyptian Revival buildings (Fig. 9-5, 9-7, 9-8). Islamic-style<br />

arches may frame or form windows (Fig. 9-11, 9-15). Some<br />

have colored glass panes.<br />

■ Doors. Doorways feature slanted sides and Egyptian<br />

columns (Fig. 9-6). Doors in Islamic-style structures may<br />

be located within horseshoe, multifoil, or ogee arches carried<br />

by piers or columns (Fig. 9-3, 9-11, 9-13).<br />

■ Roofs. Roofs usually are flat or low pitched on Egyptian<br />

Revival structures (Fig. 9-7). Islamic buildings may have<br />

multiple roofs with onion domes and minarets (Fig. 9-14).<br />

■ Later Interpretations. Egyptian and Turkish design features<br />

are not used frequently in later periods, except in<br />

countries of, or influenced by, the Middle East. In the late<br />

20th century, the most common application in Europe and<br />

America appears in buildings emphasizing entertainment,<br />

such as hotels, theaters, casinos, and theme parks in places<br />

like Las Vegas (Fig. 9-18) or Disneyworld. Structures in the<br />

Middle East reflect their Arabic or Islamic heritage, using<br />

a more contemporary vocabulary.<br />

INTERIORS<br />

Exotic interiors often are the most eclectic, combining<br />

architectural details, motifs, furniture, or decorative arts of<br />

several cultures or styles. Although this enhances their<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

� 9-19. Nave, First Presbyterian Church, 1848–1851; Nashville, Tennessee; William Strickland. Egyptian Revival.<br />

appeal, they usually represent only a room or two within<br />

houses or a particular building type. As in architecture,<br />

associations are important for choosing an exotic interior<br />

style, and particular rooms are deemed appropriate for a particular<br />

style. Egyptian Revival interiors are far less common<br />

in residences but typify rooms in public buildings of the style.<br />

Museums, zoos, and collectors decorate interiors housing<br />

their Egyptian or Middle Eastern artifacts and animals in the<br />

appropriate style. Billiard or smoking rooms, reserved for<br />

males, are most likely to be Turkish, Islamic, or Indian.<br />

Turkish corners, derived from Turkish bazaars, and extremely<br />

popular in the late 19th century in England and North<br />

America, are seen as exotic and somewhat promiscuous.<br />

Public and Private Buildings<br />

■ Types. Egyptian Revival buildings usually have an interior<br />

or interiors in the same style, particularly in fraternal<br />

temples and early-20th-century movie theaters.<br />

Smoking rooms, billiard rooms, Turkish bathrooms,<br />

male-related spaces in hotels and houses, tea rooms, and<br />

conservatories may exhibit Turkish designs and details<br />

(Fig. 9-22, 9-28, 9-30). Turkish or cozy corners are a<br />

EXOTICISM 223<br />

craze in American and English homes during the 1870s<br />

through the 1890s (Fig. 9-31, 9-32). Occupying a corner<br />

or small portion of the room, the Turkish corner is identified<br />

by curtains and/or a canopy of Turkish fabrics or<br />

rugs, divans or built-in seating with piles of pillows, Oriental<br />

rugs, and numerous accessories such as potted<br />

palms, ceramics, spears, swords, pipes, small tables,<br />

lamps, and candlesticks. Periodicals carry instructions<br />

for making cozy corners to aid owners of modest houses<br />

in following the fashion.<br />

■ Relationships. Often, there is little or no relationship<br />

between exterior style and interior character. Room associations<br />

and fashion are more likely to influence style<br />

choices.<br />

■ Color. Rich, highly saturated colors (Fig. 9-2) are<br />

associated with exotic styles. Blue, green, gold, yellow,<br />

red, and black are common for Egyptian. Turkish colors<br />

include blues, greens, purples, turquoises, reds, oranges,<br />

white, and black (Fig. 9-25, 9-26). Bold colors are usually<br />

seen against a neutral, often beige or earth-toned<br />

background.<br />

■ Lighting. Lighting fixtures exhibit forms and motifs common<br />

to exotic styles (Fig. 9-22, 9-27). Often fixtures acquired<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

224 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-20. Nave, Isaac M. Wise Temple, 1866; Cincinnati, Ohio;<br />

James K. Wilson. Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

on foreign travels are adapted to contemporary use. Mosque<br />

lamps may illuminate Turkish interiors.<br />

■ Floors. Wood floors with Oriental rugs are common in<br />

Turkish and Egyptian Revival interiors (Fig. 9-22, 9-26,<br />

9-29, 9-30, 9-34). Alternative floor coverings include<br />

animal skins and furs. Decorative tiles in various patterns<br />

may embellish vestibules, large halls, and conservatories<br />

(Fig. 9-25).<br />

■ Walls. Walls feature motifs of the style chosen. In public<br />

spaces, Egyptian architectural details, such as columns or<br />

relief sculpture, may articulate walls (Fig. 9-19, 9-23, 9-24).<br />

Spaces between architectural details may be decorated with<br />

colorful Egyptian motifs or figures. Bands of Egyptian patterning,<br />

figures, or hieroglyphs may decorate walls and<br />

columns. Wallpaper and borders with Egyptian figures and<br />

motifs are available but not common. A few landscape<br />

wallpapers in the early 19th century depict Egyptian<br />

architecture.<br />

Islamic-style arches in plaster or paneling may articulate<br />

walls or divide spaces in Turkish rooms (Fig. 9-21,<br />

9-22, 9-23, 9-26, 9-29). An alternative is ceramic tiles<br />

with flat, intricate, stylized Islamic patterns, which cover<br />

� 9-21. Stair hall and elevation, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine<br />

Arts, 1872–1876; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Frank Furness and<br />

George W. Hewitt.<br />

walls or embellish fireplace openings (Fig. 9-25). Flat or<br />

draped textiles, such as shawls, kelims, or carpets, adorn<br />

walls of Turkish interiors (Fig. 9-26, 9-32). Wallpapers<br />

and borders with Islamic patterns are an alternative for<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

EXOTICISM 225<br />

� 9-22. Hotel lobby, 1902; United States.<br />

� 9-23. Egyptian and Moorish halls, Masonic Temple, c. 1890; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Egyptian and Moorish Revival.<br />

� 9-24. Proscenium, elevation, and detail, Ada Theater, 1926; Boise, Idaho; Frederick C. Hummel. Egyptian Revival.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

226 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

textiles. Islamic patterns used on walls (Fig. 9-3) influence<br />

reform wallpaper designers, such as William Morris,<br />

who adopt their flat, colorful, and curvilinear patterns in<br />

the second half of the 19th century (see <strong>Chapter</strong> 17,<br />

“English Arts and Crafts”). Fabrics in complicated<br />

� 9-25. Arab Hall, Lord Leighton House, c. 1865; London,<br />

England; George Aitchison. Islamic Revival.<br />

DESIGN SPOTLIGHT<br />

Interiors: Stair hall and chimneypieces, Olana, 1870–1872<br />

house, 1888–1891 studio wing; Hudson, New York; Frederic<br />

E. Church, with consulting architect Calvert Vaux. Exotic/<br />

Moorish Revival. Home of the Hudson River School painter,<br />

Frederic Edwin Church, Olana’s Islamic design results from<br />

Church’s extended visit to the Middle East in 1867. Church<br />

designs the exterior and interiors with the help of architect<br />

Calvert Vaux. He makes numerous sketches for the exterior,<br />

each room, and its architectural details and decoration. The<br />

asymmetrical exterior is constructed of multicolored brick<br />

with tile accents. Islamic pointed arches, a tower, porches,<br />

balconies, and numerous windows to take advantage of the<br />

magnificent surrounding countryside. The house adapts<br />

patterns or rugs hanging from fretwork, Moorish-style<br />

arches, or spears frequently define the Turkish or cozy<br />

corner (Fig. 9-22, 9-31, 9-32). Niches, called Damascus<br />

niches, are a common Islamic characteristic for displaying<br />

ceramics or sculpture. Rooms often appear crowded<br />

with objects collected from many exotic locations.<br />

■ Windows Treatments. Lavish, layered window treatments<br />

are characteristic of exotic rooms (Fig. 9-32). Some are of<br />

Turkish textiles, such as kelims, or European imitations of<br />

them.<br />

■ Doors. Egyptian doorways (Fig. 9-19) may have slanted<br />

surrounds or be painted with Egyptian motifs. Islamic-style<br />

doors may have stenciled or inlaid decoration in geometric<br />

patterns or arabesques. Some have panels shaped like<br />

horseshoe or pointed arches. Interior doorways have<br />

portieres made of rugs, fabrics with Turkish motifs, or bands<br />

of fabrics hanging from rings (Fig. 9-28). Above may be<br />

fretwork with Moorish-style arches.<br />

■ Textiles. Egyptian motifs mixed with flowers and foliage<br />

typify Egyptian revival fabrics. The flat patterns of Indian<br />

chintzes and embroideries influence European textile and<br />

wallpaper designers from the 17th century onward. The<br />

European reinterpretation of the Indian elongated leaf<br />

pattern becomes known as paisley (Fig. 9-33). Islamic<br />

patterns especially appeal to reform textile designers who<br />

advocate flat, stylized patterns (Fig. 9-25). Textiles are<br />

important in Turkish style interiors where Oriental carpets<br />

and rugs cover floors, pillows, or seating, or hang on<br />

walls or at doorways (Fig. 9-22, 9-26, 9-31, 9-34). Turkish<br />

style interiors, like Egyptian and Islamic ones, use European<br />

textiles with Turkish patterns.<br />

■ Ceilings. Ceilings may have wallpapers or painted or<br />

plaster decorations in highly saturated colors and Egyptian<br />

or Turkish motifs, arches, and/or patterning (Fig. 9-20,<br />

Middle Eastern forms and elements to an American 19thcentury<br />

lifestyle.<br />

In the stair hall, Oriental rugs cover the stairs and floors<br />

and form the drapery at the first landing. A small<br />

columned niche holds a golden Buddha. At the second<br />

landing, pointed arches are accented above with stenciling<br />

in rich colors derived from a book of Eastern designs.<br />

Light from a window with yellow glass behind the arches<br />

illuminates the staircase. The stairhall contains some of<br />

Church’s finest objects, including Persian ceramics,<br />

brasswares, and sculpture. He uses them to direct attention<br />

to great past civilizations.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

DESIGN SPOTLIGHT<br />

�9-26 Stair hall and chimneypieces, Olana; Hudson, New York.<br />

Stenciling with exotic motifs<br />

Pointed arches<br />

Moorish style colors<br />

Oriental rugs form drapery<br />

Niche with Buddha<br />

Persian ceramics<br />

Exotic floor candlestick<br />

Moorish style table with ivory inlay<br />

EXOTICISM 227<br />

Brassware used throughout as decorative accents<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

228 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-27. Salon, George Kemp House; published in Artistic<br />

Houses, 1882; Louis Comfort Tiffany and Company.<br />

Exotic/Moorish Revival.<br />

� 9-28. Oswald Ottendorfer’s Moorish Pavilion; Manhattanville,<br />

New York; published in Artistic Homes, Vol. 1, 1883. Turkish Revival.<br />

� 9-29. Parlor, Sarah Ives Hurtt; New York; published in<br />

Artistic Homes, Vol. 1, 1883. Turkish Revival.<br />

� 9-30. Smoking room, John D. Rockefeller House, c. 1885;<br />

New York City, New York. Turkish Revival.<br />

� 9-31. Elsie de Wolfe in her cozy corner, Irving House, 1896;<br />

New York. Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

9-25, 9-27). Ceilings in public spaces may be compartmentalized<br />

and decorated with colorful Egyptian motifs or<br />

Islamic patterning.<br />

■ Later Interpretations. Occasional examples of Exotic influences<br />

appear in interiors during the late 20th century. Most<br />

examples are within entertainment facilities focused on<br />

fantasy, romance, and mystery (Fig. 9-35; see <strong>Chapter</strong> 30,<br />

“Modern Historicism”).<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

EXOTICISM 229<br />

� 9-32. Reception room, Hall House, 1896; New York City,<br />

New York. Turkish/Exotic Revival.<br />

� 9-33. Textiles: Paisley patterns, mid to late 19th century; England and the United States. Islamic/Exotic Revival.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

230 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-34. Rugs: Examples from the mid to late 19th century; Turkish, Persian, and Caucasian. Islamic/Exotic Revival.<br />

� 9-35. Later Interpretation: Living room cozy corner, 1993;<br />

Charlotte, North Carolina; Huston/Sherman. Modern Historicism.<br />

FURNISHINGS AND DECORATIVE ARTS<br />

Egyptian character manifests in furniture as motifs in<br />

classical styles, as a deliberate revival, or as copies of extant<br />

ancient pieces. Early in the 19th century, Egyptian<br />

motifs appear in French Empire, Regency, and Biedermeier<br />

(see <strong>Chapter</strong> 2, “Directoire, French Empire,” <strong>Chapter</strong> 3,<br />

“German Greek Revival, Beidermeier,” <strong>Chapter</strong> 4,<br />

“English Regency, British Greek Revival”). The later<br />

Neo-Grec (see <strong>Chapter</strong> 7, “Italianate, Renaissance<br />

Revival”), a substyle of Renaissance Revival, mixes<br />

Greek, Roman, and Egyptian. Mid-19th century design<br />

reformers adopt the slanted back with double bracing of<br />

Egyptian chairs as a sturdy and honest method of construction.<br />

Egyptian Revival furniture applies Egyptian<br />

motifs to contemporary forms with varying accuracy.<br />

Beginning in the 1880s, the Egyptian collections at the<br />

British Museum inspire English copies of stools and<br />

chairs.<br />

Moorish- or Turkish-style furnishings appear beginning<br />

in the 1870s. Some are imported; some are made in England<br />

and North America. Imports include screens, small<br />

tables, and Koran stands. In the United States, the most<br />

common manifestation of Turkish style is in upholstery or<br />

built-in seating. Seating adopts Turkish names such as divan<br />

or ottoman. Imported furniture, rugs, and decorative<br />

arts from the Middle East easily add a touch of the exotic<br />

to any interior.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

DESIGN SPOTLIGHT<br />

Furniture: Turkish parlor chairs and sofa, late 19th century;<br />

United States; by S. Karpen Brothers and Sears,<br />

Roebuck and Company. Turkish/Exotic Revival. Manufactured<br />

by S. Karpen Brothers and exhibited at the World’s<br />

Columbian Exposition in 1893, these chairs exemplify<br />

the appearance of opulence and comfort desired during<br />

the period. The deeply tufted back and seat, puffing on<br />

� 9-36 Turkish parlor chairs, late 19th century.<br />

Tufting<br />

the edges of the cushions, a fringed and tasseled skirt,<br />

rounded corners, and additional padding on seat and<br />

arms create the overstuffed Turkish upholstery that is<br />

fashionable in the 1880s and 1890s. Sears, Roebuck and<br />

Company, other companies, and manufacturers distributed<br />

similar versions.<br />

Overstuffed and heavy appearance<br />

Puffing on edges<br />

Rounded corners and padding typical<br />

Fringed and tasseled skirt<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

231

232 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-37. Moorish stools and table, c. 1890; Florence, Italy;<br />

Andre Bacceti.<br />

Wicker, which carries associations with Exoticism,<br />

becomes extremely fashionable in the second half of the<br />

19th century. Known since antiquity, manufacturers experiment<br />

with forms, materials, colors, and motifs from<br />

China, Japan, and Moorish Spain. Wicker has numerous<br />

patterns, including Egyptian.<br />

Public and Private Buildings<br />

■ Types. The Turkish-style overstuffed upholstery has no<br />

prototype in the Middle East as do many Egyptian Revival<br />

pieces, such as pianos and wardrobes. All types of furniture<br />

� 9-39. Horn furniture, late 19th century; Texas and California.<br />

� 9-38. Slipper chair, c. 1875. Egyptian Revival.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

� 9-40. Wicker seating, c. 1880s–1910s; United States.<br />

are made of wicker, including wheelchairs, cribs, cradles,<br />

baby carriages, and outdoor furniture.<br />

■ Distinctive Features. Egyptian Revival furniture displays<br />

the forms and motifs of ancient Egyptian architecture,<br />

EXOTICISM 233<br />

with slanted sides, columns, obelisks, and hieroglyphs<br />

(Fig. 9-38). Some pieces are gilded or ebonized with incising.<br />

Deep tufting and fancy trims distinguish Turkish<br />

upholstery and give the impression of comfort and opulence<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

234 VICTORIAN REVIVALS<br />

� 9-41. Decorative Arts: Clock, vases, and glassware; clocks and<br />

vases exhibited at the Centennial International Exposition of 1876<br />

in Philadelphia; United States, and Austria. Egyptian Revival.<br />

(Fig. 9-22, 9-36). Other Turkish-style furniture is light in<br />

scale and often has fretwork in typical patterns. Wicker<br />

varies from very plain to highly decorative with curlicues,<br />

beadwork, and various patterning (Fig. 9-29, 9-40).<br />

■ Relationships. Exotic rooms have the same style of furniture<br />

with the exception of Turkish upholstery, which mixes<br />

with other styles. Wicker is used on porches and conservatories<br />

and may appear in other rooms.<br />

■ Materials. Egyptian Revival and Turkish furniture<br />

usually is of dark woods, such as mahogany or rosewood.<br />

Less exotic woods are grained to imitate other woods.<br />

Embellishments consist of inlay, gilding, ebonizing,<br />

incising, ormolu mounts, or painted decorations. Inlay in<br />

Turkish furniture is of bone or ivory. Wicker is made of<br />

straw, willow, rattan, and other fibers, although most is<br />

of rattan (Fig. 9-40). It is painted red, yellow, brown,<br />

black, green, or white. Some pieces have gilding or combinations<br />

of colors.<br />

■ Seating. Egyptian Revival chairs and parlor sets have<br />

wooden frames with carved and sometimes stylized<br />

Egyptian details and upholstered backs and seats (Fig.<br />

9-38). Legs may be animal shaped with paw feet or<br />

hooves or tapered with Egyptian-style capitals. Turkishstyle<br />

overstuffed upholstery has deep tufting, fringe,<br />

and/or trim that covers the legs. Chairs and sofas often<br />

have an extra roll of stuffing around the arms and backs<br />

� 9-42. Later Interpretation: Turkish chair, 2003; available<br />

from Marco Fine Furniture. Modern Historicism.<br />

(Fig. 9-36). Cording, puffing, and pleating add visual<br />

complexity and give an impression of comfort. Turkish<br />

divans or lounges refer to deeply tufted couches without<br />

backs or arms. Turkish ottomans are large and round with<br />

tufted backs and a space for a potted palm or sculpture in<br />

the raised center. Often used in grand spaces, they are<br />

intended as a momentary seat rather than a place of relaxation.<br />

Variations of the Turkish style include chairs or<br />

sofas with round or oval backs not attached to the seats<br />

and round or oval seats. Often small and fragile, these<br />

chairs upholstered in silk or satin are used in parlors.<br />

Americans love Turkish-style rocking chairs. Some<br />

Turkish interiors use pillows on the floor for seating (Fig.<br />

9-29, 9-31). Others, particularly men’s smoking rooms<br />

and libraries, incorporate horn chairs upholstered in<br />

exotic skins or other similar horn furniture (Fig. 9-39).<br />

Usually made in western areas of the United States such<br />

as Texas, examples convey a rugged, manly character.<br />

Indoor and outdoor seating in public and private buildings,<br />

including parlor sets, often is of wicker (Fig. 9-40).<br />

Solid portions may be plainly woven or have patterns, such<br />

as stars or dippers. Cresting, backs, legs, and arms often<br />

have curving forms of fans, lattice, strapwork, arabesques,<br />

ogees, or curlicues. Some wicker seating has upholstered<br />

backs and seats, although most rely on added cushions for<br />

comfort. Ladies add their own decorative touches, such as<br />

ribbon threaded through openwork, bows, or tassels.<br />

■ Tables. Egyptian Revival tables exhibit Egyptian<br />

motifs, such as figures, heads, or sphinxes. Some have<br />

slender tapered legs with incising and stylized carving.<br />

Obelisks or pylon-shaped pedestals display sculpture<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

2009933390

2009933390<br />

or plants. Hexagonal or octagonal occasional tables<br />

imported from the Middle East are of dark woods with<br />

ivory or mother-of-pearl inlay in geometric patterns (Fig.<br />

9-27, 9-37). Small stands, originally designed to hold the<br />

Koran, rest upon tables and hold books. Wicker tables<br />

and stands may match seating.<br />

■ Storage. Wardrobes, cupboards, and commodes may<br />

have the slanted sides and fronts of Egyptian gateways,<br />

Egyptian columns or figures, and other Egyptian motifs.<br />

Tops may have cavetto cornices or rounded moldings.<br />

Some pieces are ebonized with gilding, incising, and<br />

painted decorations. Wicker cupboards or chests of drawers<br />

are not as common as wicker seating is.<br />

■ Beds. Egyptian-style beds are very rare. Beds for children,<br />

cribs, and cradles may be in plain or fancy wicker.<br />

■ Upholstery. Textiles for upholstery include damasks, velvets,<br />

cut velvets, brocades, satins, silks, Oriental rugs, cottons<br />

or other fabrics either plain or with Egyptian and<br />

Turkish motifs or patterns, and leather. In the 1880s,<br />

Liberty and Company in London sells hugely popular silk<br />

textiles with anglicized Middle Eastern patterns in pastel<br />

blues, greens, corals, yellows, and golds.<br />

EXOTICISM 235<br />

■ Decorative Arts. Egyptian Revival decorative arts, such as<br />

clocks, porcelains, or vases, feature Egyptian architectural<br />

details, including obelisks, and motifs, such as sphinxes.<br />

Sevres and other porcelain factories make dinner sets<br />

painted with Egyptian motifs and architecture. Egyptian<br />

mantel sets consisting of a clock and vases or obelisks are<br />

common in the second half of the 19th century (Fig. 9-41).<br />

Imported brass objects, ceramics, folding screens, spears,<br />

daggers, plates, tiles, and potted palms define Turkish or<br />

Moorish interiors. Ceramics from India and the Middle East<br />

inspire tiles and other ceramics with intricate flat patterns<br />

in turquoise, blue, green, and red. The glass of Louis Comfort<br />

Tiffany and others draws inspiration from the shapes,<br />

forms, and colors of Egyptian, Islamic, and Oriental glass<br />

and ceramics. Wicker mirrors, plant stands, birdcages, and<br />

the like add a touch of exoticism to many rooms.<br />

■ Later Interpretations. Furnishings and decorative arts reflecting<br />

an Exotic influence rarely appear in later periods,<br />

unless in concert with custom-designed Exotic interiors,<br />

such as those in entertainment facilities or libraries of the<br />

late 20th century (Fig. 9-42). Art Deco in the 1920s and<br />

1930s adapts Egyptian motifs and colors.<br />

Architecture and Interior Design from the 19th Century: An Integrated History, Volume 2, by Buie Harwood, Bridget May, Ph.D., and Curt Sherman.<br />

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2009 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.