Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

14 Bostock, H. and Bergmans, J. (1994) Post-tetanic excitability<br />

changes and ectopic d<strong>is</strong>charges in a human motor axon. Brain<br />

117, 913–928<br />

15 David, G. et al. (1993) Activation of internodal potassium<br />

conductance in rat myelinated axons. J. Physiol. 472, 177–202<br />

16 Kapoor, R. et al. (1993) Internodal potassium currents can generate<br />

ectopic impulses in mammalian myelinated axons. Brain Res.<br />

611, 165–169<br />

17 Smith, K.J. and McDonald, W.I. (1980) Spontaneous and<br />

mechanically evoked activity due to a central demyelinating<br />

lesion. Nature 286, 154–156<br />

18 Baker, M. and Bostock, H. (1992) Ectopic activity in demyelinated<br />

spinal root axons of <strong>the</strong> rat. J. Physiol. 451, 539–552<br />

19 Frankenhaueser, B. and Hodgkin, A.L. (1956) The after-effects of<br />

impulses in <strong>the</strong> giant nerve fibres of Loligo. J. Physiol. 131, 341–376<br />

20 Kapoor, R. et al. (1997) Slow sodium-dependent potential<br />

oscillations contribute to ectopic firing in mammalian<br />

demyelinated axons. Brain 120, 647–652<br />

21 Taylor, C.P. (1993) Na � currents that fail to inactivate. Trends<br />

Neurosci. 16, 455–459<br />

22 Crill, W.E. (1996) Pers<strong>is</strong>tent sodium current in mammalian central<br />

neurons. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 58, 349–362<br />

23 Baker, M.D. and Bostock, H. (1998) Inactivation of macroscopic<br />

late Na � currents in sensory neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 80,<br />

2538–2549<br />

<strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>?<br />

Larry W. Swanson<br />

M.D. Baker – Axonal flip-flops and oscillators V IEWPOINT<br />

24 Bostock, H. and Rothwell, J.C. (1997) Latent addition in motor and<br />

sensory fibres of human peripheral nerve. J. Physiol. 498, 277–294<br />

25 Stys, P.K. et al. (1993) Non-inactivating, TTX-sensitive Na �<br />

conductance in rat optic nerve axons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.<br />

87, 4212–4216<br />

26 Bostock, H. and Sears, T.A. (1978) The internodal axon membrane:<br />

electrical excitability and continuous conduction in segmental<br />

demyelination. J. Physiol. 280, 273–301<br />

27 Bostock, H. et al. (1981) The effects of 4-aminopyridine and<br />

teraethylammonium ions on normal and demyelinated<br />

mammalian nerve fibres J. Physiol. 313, 301–315<br />

28 Baker, M.D. (2000) Selective block of late Na � current by local<br />

anaes<strong>the</strong>tics in rat large sensory neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol.<br />

129, 1617–1626<br />

29 Raman, I.M. et al. (1997) Altered subthreshold sodium currents<br />

and d<strong>is</strong>rupted firing patterns in Purkinje neurons of Scn8a mutant<br />

mice. Neuron 19, 881–891<br />

30 De Miera, E.V.S. et al. (1997) Molecular characterization of <strong>the</strong><br />

sodium channel subunits expressed in mammalian cerebellar<br />

Purkinje cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 7059–7064<br />

31 Smith, M.R. et al. (1998) Functional analys<strong>is</strong> of <strong>the</strong> mouse Scn8a<br />

sodium channel. J. Neurosci. 18, 6093–6102<br />

32 Caldwell, J.H. et al. (2000) Sodium channel Na v 1.6 <strong>is</strong> localized at<br />

nodes of Ranvier, dendrites, and synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.<br />

U. S. A. 97, 5616–5620<br />

From a structural perspective, <strong>the</strong>re are ten basic parts of <strong>the</strong> vertebrate CNS that are almost<br />

universally agreed upon.These parts have been grouped in at least five different ways corresponding<br />

to five different <strong>the</strong>ories about its basic plan or architecture.Two classical models that remain<br />

popular today are derived from (1) comparative anatomy and <strong>the</strong> body’s segmental organization,<br />

and (2) comparative embryology and <strong>the</strong> neural tube’s transverse and longitudinal organization.<br />

A new approach <strong>is</strong> concerned with deciphering <strong>the</strong> genetic program that assembles <strong>the</strong><br />

nervous system during embryogenes<strong>is</strong>; how it will correspond to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r models remains to<br />

be determined. The simplest current model to explain <strong>the</strong> organization of <strong>the</strong> mammalian<br />

nervous system involves a segmental trunk that mediates reflex sensory–motor functions, and<br />

suprasegmental cerebral hem<strong>is</strong>pheres and cerebellum.<br />

Trends Neurosci. (2000) 23, 519–527<br />

‘…anatomy should not be bound by any rule but ought to<br />

change as frequently as d<strong>is</strong>sections are begun.’ Nicolaus Steno<br />

(1669) 1<br />

‘The terminology of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>is</strong> in great confusion.’ C. Judson<br />

Herrick (1915) 2<br />

TWO YEARS AGO, Gorica Petrovich and I wrote an<br />

essay for th<strong>is</strong> journal entitled ‘<strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> amygdala?’<br />

3 Not surpr<strong>is</strong>ingly, it ra<strong>is</strong>ed broader, even more<br />

obvious and important questions that we seldom<br />

pause to think about in th<strong>is</strong> relentlessly reduction<strong>is</strong>tic<br />

day and age, including, what are <strong>the</strong> basic parts of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>brain</strong>, or even more to <strong>the</strong> point, what do we mean by<br />

<strong>the</strong> word ‘<strong>brain</strong>’ itself? An overview of how some of<br />

<strong>the</strong> major contributors to <strong>the</strong> neuroanatomical literature<br />

have addressed <strong>the</strong>se questions over <strong>the</strong> centuries<br />

has revealed two surpr<strong>is</strong>ing insights that may be worth<br />

sharing. First, my understanding (and I doubt if I am<br />

alone in th<strong>is</strong>) of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>’s basic parts goes back to<br />

dogmatic, essentially undocumented statements in<br />

recent textbooks, and similarly, <strong>the</strong> prec<strong>is</strong>e meaning of<br />

certain terms such as ‘<strong>brain</strong>stem’, ‘basal ganglia’, and<br />

‘cerebrum’ has never been entirely clear to me,<br />

although I usually have not worried too much about<br />

it. Second, even though <strong>the</strong> nomenclature nightmare<br />

referred to by Herrick 2 in <strong>the</strong> quote at <strong>the</strong> beginning of<br />

<strong>the</strong> article certainly has not gone away 4 , <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> actually<br />

a great deal of information embedded within <strong>the</strong><br />

confusion. On one hand, we will see that <strong>the</strong>re are on<br />

<strong>the</strong> order of ten generally agreed upon parts of <strong>the</strong> vertebrate<br />

CNS (ignoring d<strong>is</strong>putes about what <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

called), and on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand <strong>the</strong>se parts have been<br />

grouped in at least five different ways, constituting five<br />

‘<strong>the</strong>ories of <strong>brain</strong> architecture’, to use Baer’s 5 insightful<br />

phrase. Because <strong>the</strong>re seem to be no compelling reasons<br />

for choosing among <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>ories or models at<br />

<strong>the</strong> present time, <strong>the</strong>y provide a set of fresh ways to<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> basic plan of <strong>the</strong> CNS – especially important<br />

long-term goals of developmental and systems<br />

neuroscience. The subject of regional neuroanatomy<br />

might seem irrelevant to molecular and cellular neuroscience,<br />

until one comes to view <strong>the</strong> function of a gene<br />

0166-2236/00/$ – see front matter © 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S0166-2236(00)01639-8 TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000 519<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The author <strong>is</strong><br />

grateful to Hugh<br />

Bostock for<br />

innumerable useful<br />

d<strong>is</strong>cussions and<br />

Mat<strong>the</strong>w Kiernan<br />

for h<strong>is</strong> comments<br />

on <strong>the</strong> manuscript.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> work was<br />

supported by <strong>the</strong><br />

MRC.<br />

Larry W. Swanson<br />

<strong>is</strong> at <strong>the</strong><br />

Neuroscience<br />

Program, The<br />

University of<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

California, Los<br />

Angeles,<br />

CA 90089-2520,<br />

USA.

V IEWPOINT<br />

‘Brain’<br />

(c. 4200 BC)<br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture<br />

Dual <strong>brain</strong><br />

(c. 340 BC)<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle<br />

or neuron in terms of its role within a particular neural<br />

system or part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>. Th<strong>is</strong> brings us back to <strong>the</strong><br />

two questions posed at <strong>the</strong> beginning of th<strong>is</strong> review.<br />

CNS nomenclature in antiquity<br />

From one perspective, <strong>the</strong> h<strong>is</strong>tory of neuroanatomical<br />

nomenclature can be traced back more than 6000<br />

years (Fig. 1). An equivalent to <strong>the</strong> Engl<strong>is</strong>h word<br />

‘<strong>brain</strong>’ <strong>is</strong> found in an Egyptian manuscript composed<br />

~4200 BC (Ref. 6), although its most famous occurrence<br />

<strong>is</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus (a 1700 BC copy<br />

of an Egyptian manuscript composed some 1500 years<br />

earlier), where 13 cases of skull fracture caused by<br />

war injuries are d<strong>is</strong>cussed 7–10 . In approximately 340 BC<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle publ<strong>is</strong>hed <strong>the</strong> first surviving account of <strong>brain</strong><br />

d<strong>is</strong>sections 10 . He d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>hed <strong>the</strong> parencephalon or<br />

small <strong>brain</strong> (cerebellum in Latin) from <strong>the</strong> encephalon<br />

or large <strong>brain</strong> (cerebrum in Latin), which extends<br />

down through <strong>the</strong> back as <strong>the</strong> spinal marrow (<strong>the</strong><br />

marrow of <strong>the</strong> back bone or vertebral column; our<br />

spinal cord). Th<strong>is</strong> was <strong>the</strong> first <strong>the</strong>ory or model of CNS<br />

architecture and cons<strong>is</strong>ted of three parts based on <strong>the</strong><br />

simplest gross anatomical criteria, that <strong>is</strong> a small <strong>brain</strong><br />

attached to a large <strong>brain</strong>, which in turn <strong>is</strong> attached to<br />

a spinal marrow (Fig. 2a). Th<strong>is</strong> dual (large and small)<br />

<strong>brain</strong> model was followed unaltered for about 1800<br />

years, until <strong>the</strong> work of Vesalius, described below.<br />

Before progressing to <strong>the</strong> European Rena<strong>is</strong>sance it<br />

<strong>is</strong> important to note that Ar<strong>is</strong>totle started <strong>the</strong> unenviable<br />

tradition of ambiguous terminology in<br />

neuroanatomy referred to by Herrick 2 . Ar<strong>is</strong>totle used<br />

exactly <strong>the</strong> same word, encephalon, in two very different<br />

ways: first, in its oldest sense, as <strong>the</strong> ‘marrow’ of<br />

<strong>the</strong> skull, and second, as a name for h<strong>is</strong> ‘large <strong>brain</strong>’.<br />

As with all such ambiguities, <strong>the</strong> meaning of a specific<br />

example of <strong>the</strong> word can only be inferred from its context,<br />

which <strong>is</strong> a crucial problem today because keywords<br />

with more than one meaning might be used<br />

(without context) for database queries.<br />

Interestingly, th<strong>is</strong> ambiguity was recognized, and<br />

even dealt with, very quickly in classical antiquity. As<br />

Galen noted 10 , in approximately 290 BC <strong>the</strong> founder of<br />

human anatomy, Herophilus, might have proposed<br />

<strong>the</strong> unequivocal term enkranon for <strong>the</strong> neural contents<br />

of <strong>the</strong> skull compared with Ar<strong>is</strong>totle’s specialized<br />

use of ‘encephalon’ for <strong>the</strong> large <strong>brain</strong>. Unfortunately<br />

520 TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000<br />

Will<strong>is</strong><br />

1644<br />

Varolio<br />

1573<br />

Vesalius<br />

1543<br />

Malpighi<br />

1672<br />

Dual <strong>brain</strong><br />

Edinger<br />

1908<br />

1980s<br />

Segmental<br />

Segmental<br />

Segmental<br />

Developmental<br />

Evolutionary<br />

Genomic<br />

trends in Neurosciences<br />

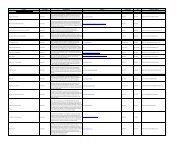

Fig. 1. Evolutionary h<strong>is</strong>tory of major <strong>the</strong>ories on regional organization of <strong>the</strong> CNS. In <strong>the</strong> 16th and 17th centuries <strong>the</strong>re<br />

was an ‘explosion’ of <strong>the</strong>ories regarding <strong>the</strong> basic regional or topographic organization of <strong>the</strong> CNS after <strong>the</strong> ‘dual <strong>brain</strong>’<br />

account of Ar<strong>is</strong>totle was introduced in classical antiquity (~340 BC). Two new classes of <strong>the</strong>ory, evolutionary and genomic,<br />

were added in <strong>the</strong> 20th century; <strong>the</strong> former has had little substantial influence, whereas <strong>the</strong> latter <strong>is</strong>, just now, maturing.<br />

th<strong>is</strong> useful d<strong>is</strong>tinction never caught<br />

on. From an early time, however,<br />

careful anatom<strong>is</strong>ts began to speak of<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>brain</strong> proper’ (or <strong>the</strong> cerebrum<br />

proper or <strong>the</strong> encephalon proper)<br />

when referring to Ar<strong>is</strong>totle’s large<br />

<strong>brain</strong>, and <strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>brain</strong>’ or ‘<strong>brain</strong> in<br />

general’ when referring to <strong>the</strong><br />

neural contents of <strong>the</strong> skull.<br />

Incidentally, a curious tradition has<br />

evolved in Engl<strong>is</strong>h (which probably<br />

dates back to 1755 and <strong>the</strong> publication<br />

of Samuel Johnson’s great<br />

dictionary 51 ), where frequently <strong>the</strong><br />

part of <strong>the</strong> CNS in <strong>the</strong> skull <strong>is</strong><br />

referred to as <strong>the</strong> encephalon or<br />

<strong>brain</strong>, whereas <strong>the</strong> large <strong>brain</strong> <strong>is</strong><br />

referred to as <strong>the</strong> cerebrum. Once<br />

one <strong>is</strong> aware of ambiguities associated<br />

with definitions and uses of<br />

<strong>the</strong> words ‘<strong>brain</strong>’, ‘cerebrum’ and<br />

‘encephalon’ it <strong>is</strong> amazing how often <strong>the</strong>ir meaning <strong>is</strong><br />

unclear when reading <strong>the</strong> literature carefully.<br />

The Rena<strong>is</strong>sance explosion of models: segmental<br />

and developmental<br />

With <strong>the</strong> publication in 1543 of h<strong>is</strong> truly revolutionary<br />

masterpiece, De Humani Corpor<strong>is</strong> Fabrica 52 ,<br />

Vesalius codified Rena<strong>is</strong>sance anatomy, which was<br />

based on two principles: direct observation instead of<br />

reliance on classical texts, and use of <strong>the</strong> new, natural<strong>is</strong>tic<br />

art to illustrate results (h<strong>is</strong> principal art<strong>is</strong>t, Kalkar,<br />

was in all probability from Titian’s studio). Similar to<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle, Vesalius proposed a tripartite div<strong>is</strong>ion of our<br />

CNS, but th<strong>is</strong> time <strong>the</strong> parcellation was based on much<br />

better structural analys<strong>is</strong> that now included a consideration<br />

of <strong>the</strong> nerves 17 . At <strong>the</strong> core of Vesalius’s description<br />

was <strong>the</strong> dorsal medulla, which corresponds to our<br />

spinal cord, medulla and pons (Figs 2,3). He extended<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle’s ‘spinal medulla’ up into <strong>the</strong> cranium<br />

because <strong>the</strong> whole structure <strong>is</strong> associated with a series<br />

of major paired nerves beginning rostrally with our<br />

trigeminal nerve, and thus excluding <strong>the</strong> ‘atypical’<br />

nerves associated more rostrally with <strong>the</strong> eye and olfactory<br />

apparatus. Vesalius attached h<strong>is</strong> version of <strong>the</strong><br />

large <strong>brain</strong> (now <strong>the</strong> Latin cerebrum instead of <strong>the</strong><br />

Greek encephalon) to <strong>the</strong> rostral end of <strong>the</strong> dorsal<br />

medulla or ‘trunk’ (derived from Will<strong>is</strong>, see below), and<br />

<strong>the</strong> small <strong>brain</strong> (now <strong>the</strong> Latin cerebellum instead of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Greek parencephalon) to <strong>the</strong> dorsal aspect of <strong>the</strong><br />

trunk, just caudal to <strong>the</strong> cerebrum (Fig. 2).<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> was <strong>the</strong> first example of a general class of<br />

model wherein a central trunk that generates ‘segmental’<br />

nerves <strong>is</strong> associated with two ‘suprasegmental’<br />

structures, <strong>the</strong> cerebrum and cerebellum, as specifically<br />

articulated at <strong>the</strong> close of <strong>the</strong> 19th century by<br />

Meyer 53 . Based on <strong>the</strong> origin of regularly spaced nerve<br />

pairs, Vesalius was able to escape from <strong>the</strong> all too easy<br />

convention (advocated by Galen and still common<br />

today) of dividing what we call <strong>the</strong> CNS into a part<br />

within <strong>the</strong> skull and a part within <strong>the</strong> vertebral column<br />

(<strong>brain</strong> as a whole and spinal cord, respectively).<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> double meaning of <strong>the</strong> word<br />

cerebrum referred to in <strong>the</strong> preceding section was evident<br />

even in h<strong>is</strong> text. For example, at <strong>the</strong> beginning<br />

of chapter four in Book VII, Vesalius wrote:<br />

‘D<strong>is</strong>sectionum professores, universum cerebrum in anterius,

quod cerebrum, & in posterius, quod cerebellum vocant:<br />

deinde anterius in dextrum & sin<strong>is</strong>trum dividere resolent…’,<br />

which Singer 17 has translated as ‘By professors<br />

of d<strong>is</strong>section <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>is</strong> customarily divided into an<br />

anterior part, which <strong>the</strong>y call ‘cerebrum’, and a posterior,<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘cerebellum’, <strong>the</strong> anterior (being divided)<br />

into right and left’. Note that Singer has used ‘<strong>brain</strong>’<br />

instead of ‘cerebrum’ at <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> sentence<br />

(even though Vesalius used cerebrum), and in <strong>the</strong> title<br />

of h<strong>is</strong> book, Vesalius on <strong>the</strong> Human Brain 17 .<br />

Thirty years later, in 1573, Varolio (who d<strong>is</strong>covered<br />

<strong>the</strong> pons, or more accurately, our middle cerebellar<br />

peduncles) came up with a second interpretation of<br />

where <strong>the</strong> trunk ends rostrally 26 . He showed <strong>the</strong> trunk<br />

extending all <strong>the</strong> way to <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> cerebral hem<strong>is</strong>pheres<br />

(thus including our inter<strong>brain</strong> or diencephalon),<br />

and he referred to <strong>the</strong> whole trunk as <strong>the</strong><br />

spinal marrow ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> dorsal marrow of<br />

Vesalius (Figs 2,3), which was probably an unfortunate<br />

choice because <strong>the</strong> rostral end <strong>is</strong> not within <strong>the</strong> spinal<br />

column; that <strong>is</strong>, <strong>the</strong> term <strong>is</strong> obviously inaccurate.<br />

The final variant of <strong>the</strong> ‘segmental’ model from<br />

th<strong>is</strong> era appeared in <strong>the</strong> first book devoted exclusively<br />

to nervous system structure and function,<br />

Will<strong>is</strong>’s classic Cerebri Anatomie, where <strong>the</strong> word neurology<br />

was first used 34 . Will<strong>is</strong> extended <strong>the</strong> trunk<br />

even far<strong>the</strong>r rostrally, to include what he identified<br />

and named <strong>the</strong> striate body (<strong>the</strong> non-cortical part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> cerebral hem<strong>is</strong>phere, Fig. 3 and Table 1).<br />

However, he introduced a major new div<strong>is</strong>ion: <strong>the</strong><br />

part of <strong>the</strong> trunk in <strong>the</strong> skull he referred to by <strong>the</strong><br />

synonyms oblong marrow, medullary stem and<br />

medullary trunk – in d<strong>is</strong>tinction to <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong><br />

trunk in <strong>the</strong> spinal or vertebral canal (<strong>the</strong> spinal marrow).<br />

So accordingly, <strong>the</strong>re were oblong and spinal<br />

div<strong>is</strong>ions of <strong>the</strong> marrow or trunk. Th<strong>is</strong> advance contains<br />

an initial concept of a ‘<strong>brain</strong>stem’, although<br />

th<strong>is</strong> term does not appear to have been used until <strong>the</strong><br />

19th century (Table 1). Note that <strong>the</strong> first definition<br />

of <strong>the</strong> medulla oblongata (oblong marrow) included<br />

what today we call <strong>the</strong> basal ganglia/cerebral nuclei,<br />

inter<strong>brain</strong>, mid<strong>brain</strong> and hind<strong>brain</strong>. Essentially,<br />

Will<strong>is</strong> pointed out that <strong>the</strong> cranial nerves ar<strong>is</strong>e from<br />

<strong>the</strong> oblong marrow, whereas <strong>the</strong> spinal nerves ar<strong>is</strong>e<br />

from <strong>the</strong> spinal marrow.<br />

Will<strong>is</strong> provides ano<strong>the</strong>r classic example of how<br />

nomenclature can become confused for no apparent<br />

reason. Since <strong>the</strong> time of Galen our superior and inferior<br />

colliculi (corpora quadrigemini, tectum) had been<br />

referred to as <strong>the</strong> testes and nates (buttocks), respectively.<br />

However, Will<strong>is</strong> inexplicably reversed th<strong>is</strong>,<br />

despite what would seem to be an unforgettable explanation<br />

of Galen’s terminology by Vesalius 17 , ‘Th<strong>is</strong> part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> cerebrum graphically represents <strong>the</strong> two nates<br />

connected toge<strong>the</strong>r. But since <strong>the</strong> upper part even<br />

more resembles <strong>the</strong> testes because of that gland (<strong>the</strong><br />

pineal) which <strong>is</strong> like a pen<strong>is</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Ancients, who traditionally<br />

trained youths in <strong>the</strong> home in verbal d<strong>is</strong>tinctions,<br />

called that part DIDYMOS. We, imitating <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

name it testes or gemelli. Since in <strong>the</strong> hind and lower<br />

part of th<strong>is</strong> body <strong>is</strong> placed <strong>the</strong> orifice of <strong>the</strong> passage<br />

from <strong>the</strong> third ventricle to <strong>the</strong> fourth, and since th<strong>is</strong><br />

orifice has some resemblance to <strong>the</strong> anus, and since in<br />

<strong>the</strong> hind part of th<strong>is</strong> area <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> a transverse linear<br />

impression separating <strong>the</strong> upper parts from <strong>the</strong> lower,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ancients as I believe, gave to th<strong>is</strong> region <strong>the</strong> name<br />

GLOUTION (GLOUTOS � buttock)’.<br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture V IEWPOINT<br />

Malpighi (who proved Harvey’s model of <strong>the</strong> circulation<br />

of <strong>the</strong> blood by d<strong>is</strong>covering <strong>the</strong> capillary connection<br />

between arteries and veins, and <strong>is</strong> considered<br />

<strong>the</strong> founder of h<strong>is</strong>tology) provided <strong>the</strong> final classical<br />

model of CNS organization in 1672 (Ref. 37), based on<br />

embryology in <strong>the</strong> chick (Figs 2,3). He described and<br />

beautifully illustrated how at very early stages of<br />

development <strong>the</strong> nervous system seems to be associated<br />

with a plate-like structure that <strong>is</strong> broad rostrally<br />

and tapers caudally. Then, one can see three sequential<br />

vesicles or swellings in <strong>the</strong> broad rostral area that<br />

corresponds to <strong>the</strong> future <strong>brain</strong>. Finally, <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> a<br />

series of five sequential vesicles in <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong> region,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> most rostral vesicle actually being paired, <strong>the</strong><br />

developing eyes lying on ei<strong>the</strong>r side of <strong>the</strong> second<br />

vesicle (which he seems to have associated with <strong>the</strong><br />

optic thalamus of Will<strong>is</strong>, our inter<strong>brain</strong>), and <strong>the</strong> third<br />

vesicle (which he called <strong>the</strong> cr<strong>is</strong>tate vesicle and thus<br />

d<strong>is</strong>covered our mid<strong>brain</strong>) also being paired. How Baer<br />

named <strong>the</strong> same vesicles in a way that <strong>is</strong> still followed<br />

today <strong>is</strong> considered below, but <strong>the</strong> important point<br />

here <strong>is</strong> that Malpighi d<strong>is</strong>covered a fundamental transverse<br />

organization of <strong>the</strong> neural tube, and thus, presumably,<br />

of <strong>the</strong> adult CNS.<br />

In summary, by 1672 <strong>the</strong>re were three general models<br />

of CNS organization: <strong>the</strong> dual <strong>brain</strong> model of<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle; <strong>the</strong> segmental model of Vesalius, Varolio, and<br />

Will<strong>is</strong>; and <strong>the</strong> embryological model of Malpighi. By<br />

th<strong>is</strong> time, six basic parts of <strong>the</strong> CNS had been identified,<br />

although <strong>the</strong> definition of several of <strong>the</strong>m varied with<br />

different authors. These parts included <strong>the</strong> cerebrum,<br />

striate body (basal ganglia/cerebral nuclei), optic<br />

thalamus (inter<strong>brain</strong>), cr<strong>is</strong>tate vesicle (mid<strong>brain</strong>),<br />

cerebellum, and spinal or dorsal marrow (spinal cord).<br />

How <strong>the</strong>se three models evolved will now be examined.<br />

The dual <strong>brain</strong> model<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle’s basic model of a small or posterior <strong>brain</strong><br />

attached to a large or anterior <strong>brain</strong>, which in turn <strong>is</strong><br />

attached to <strong>the</strong> spinal marrow or cord, exerted a considerable<br />

influence well into <strong>the</strong> 19th century, but <strong>is</strong><br />

now largely forgotten. Never<strong>the</strong>less, a crucial part of it<br />

has survived in a convoluted way, caused mainly by<br />

<strong>the</strong> pioneering work of Vieussens 13 , who in 1684 was<br />

<strong>the</strong> first to begin subdividing and <strong>the</strong>n extending<br />

Will<strong>is</strong>’s corpora striata, which he called <strong>the</strong> corpora<br />

striata inferiora (essentially <strong>the</strong> anterior striate bodies).<br />

Because he used Ar<strong>is</strong>totle’s model, he went on to<br />

describe Will<strong>is</strong>’s optic thalamus (inter<strong>brain</strong>) as <strong>the</strong> corpora<br />

striata superna posterior (essentially <strong>the</strong> posterior<br />

striate bodies), and <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>brain</strong>stem’ (our<br />

mid<strong>brain</strong> and hind<strong>brain</strong>) as <strong>the</strong> corpora striata media.<br />

Many years later <strong>the</strong> influential neuroanatom<strong>is</strong>t,<br />

Reil 10,15 referred to <strong>the</strong> first two div<strong>is</strong>ions as <strong>the</strong> great<br />

cerebral nucleus, with an anterior part (Will<strong>is</strong>’s striate<br />

body) and a posterior part (Will<strong>is</strong>’s optic thalamus, our<br />

inter<strong>brain</strong>). Then, only a year later in 1810, <strong>the</strong> even<br />

more influential neuroanatomical work of Gall and<br />

Spurzheim 16,59 referred to <strong>the</strong> same features as <strong>the</strong> great<br />

cerebral ganglion, with its anterior and posterior parts.<br />

By 1876, Ferrier 36 would refer to <strong>the</strong> great cerebral<br />

nucleus or ganglion as <strong>the</strong> basal ganglia, <strong>the</strong> first reference<br />

to th<strong>is</strong> term that I have found thus far. It remained<br />

for <strong>the</strong> majority of leading 20th-century neuroanatom<strong>is</strong>ts<br />

to restrict <strong>the</strong> term ‘basal ganglia’ (‘basal<br />

nuclei’) to its original meaning, <strong>the</strong> corpus striatum<br />

of Will<strong>is</strong>, that <strong>is</strong>, <strong>the</strong> basal nuclei of <strong>the</strong> cerebral<br />

TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000 521

V IEWPOINT<br />

Dual <strong>brain</strong><br />

Segmental<br />

Developmental<br />

Striate<br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture<br />

Antiquity to end of <strong>the</strong> 17th century<br />

(classical)<br />

ENCEPHALON<br />

Cerebrum (cortex)<br />

body<br />

INF<br />

T N<br />

Vesalius (1543) 17<br />

CEREBELLUM<br />

522 TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000<br />

DORSAL MARROW<br />

SPINAL MARROW<br />

Varolio (1573) 26 , Aranzi (1587) 27<br />

Optic<br />

thalamus<br />

N<br />

T<br />

Encephalon (<strong>brain</strong>) =<br />

encephalon (proper)<br />

PAR-<br />

+ parencephalon<br />

ENCEPH.<br />

Cerebellum<br />

(cortex)<br />

Will<strong>is</strong> (1664) 34<br />

SPINAL MARROW<br />

Ar<strong>is</strong>totle (c. 340 BC) 10 , Mondino (1316) 10 , Berengario (1523) 11 , Dryander (1536) 12<br />

CEREBRUM<br />

CEREBRUM<br />

Terminal vesicle<br />

[Optic Cr<strong>is</strong>tate<br />

thalamus] vesicle<br />

Cerebrum (<strong>brain</strong>) =<br />

cerebrum (proper)+<br />

cerebellum<br />

CEREBELLUM<br />

Cerebellar<br />

vesicle<br />

Malpighi (1673) 37<br />

Oblong marrow,<br />

medullary stem/trunk<br />

Spinal marrow<br />

Brain vesicles and spinal medulla<br />

(transverse div<strong>is</strong>ions)<br />

Spinal medulla<br />

Fig. 2. Neuroanatomical nomenclature. The main ways of subdividing<br />

<strong>the</strong> CNS are shown in <strong>the</strong> column on <strong>the</strong> left. Note that <strong>the</strong> dual <strong>brain</strong><br />

and segmental models involve a large and a small <strong>brain</strong> attached to a<br />

central core of variable length, whereas <strong>the</strong> developmental model features<br />

a rostrocaudally arranged series of vesicles. In <strong>the</strong> early 20th-century,<br />

evolutionary models were introduced and towards <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong><br />

century a genomic approach began to emerge. By now <strong>the</strong>re are at least<br />

ten basic parts or regions that are widely accepted (d<strong>is</strong>regarding nomenclature<br />

debates that are usually of a <strong>the</strong>oretical nature). These parts are<br />

shown in <strong>the</strong> small diagram to <strong>the</strong> right, without imposing any assumptions<br />

about how <strong>the</strong>y are grouped. By illustrating <strong>the</strong>ir topographic relationships,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have a very specific meaning and <strong>the</strong>y can be used to<br />

compare and describe any of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r schemes in th<strong>is</strong> chart. The flatmap<br />

shows <strong>the</strong> right side of <strong>the</strong> CNS, with rostral to <strong>the</strong> left and caudal to <strong>the</strong><br />

right; its construction <strong>is</strong> d<strong>is</strong>cussed in Ref. 50. Abbreviations: cereb., cerebral;<br />

cereb. ped., cerebral peduncle; corp. Quad., corpus quadrigemina;<br />

d. thalamus, dorsal thalamus; epi., epithalamus; gang., ganglion; hypothal.,<br />

hypothalamus; INF, infundibulum; m., metathalamus; Met.,<br />

metencephalon; Myel., myelencephalon; N, nates; PARENCEPH., parencephalon;<br />

pars mam. hypo., pars mammillar<strong>is</strong> hypothalamus; p. opt.<br />

hypo., pars opticus hypothalamus; Rhombenceph., rhombencephalon;<br />

SYN, synencephalon; T, testes; teg., tegmentum; tel. imp., telencephalon<br />

impar; thal., thalamus; vent. thal., ventral thalamus.<br />

Cerebral cortex<br />

(hem<strong>is</strong>pheric ganglion)<br />

Anterior<br />

cereb. Posterior<br />

gang.<br />

cerebral<br />

ganglion<br />

Cerebral cortex<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Striate<br />

corp.<br />

quad.<br />

body Optic<br />

thalamus Cereb.<br />

pedun.<br />

Pons Medulla<br />

N<br />

T<br />

Haller (1781) 18 , Bell (1802) 19 , Leuret and Gratiolet (1839–57) 20 , Kölliker (1854) 21 , Luys (1865) 22<br />

Cereb.<br />

pedun.<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Pons<br />

Cerebral cortex<br />

Great cerebral ganglia<br />

(cerebral nuclei, basal ganglia)<br />

Primitive, medial, ascending<br />

(cerebral) ganglion<br />

Spinal cord<br />

Vieussens (1684) 13 , Monro (1783) 14 , Reil (1809) 15 , Gall and Spurzheim (1809) 16<br />

Reichert (1859) 28 , Schwalbe (1881) 29<br />

Cerebrum (cortex)<br />

body<br />

18th to mid-19th century<br />

(late classical)<br />

Cerebral cortex<br />

Striate<br />

body Optic<br />

thalamus<br />

Striate<br />

Optic<br />

thalamus<br />

End<strong>brain</strong><br />

FOREBRAIN<br />

corp.<br />

quad.<br />

corp.<br />

quad.<br />

Mid<strong>brain</strong><br />

MID-<br />

BRAIN<br />

Cerebellum<br />

(cortex)<br />

Ann.<br />

Prot.<br />

Pons Medulla<br />

Longet (1842) 35 , Ferrier (1876) 36<br />

Inter<strong>brain</strong><br />

corp.<br />

quad.<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Baer (1837) 5 , Edinger (1885) 38<br />

CTX<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Pons<br />

Medulla<br />

Cerebrum<br />

Spinal marrow<br />

Cerebrum<br />

Brain stem<br />

Spinal marrow<br />

Brain stem<br />

Spinal marrow<br />

HINDBRAIN<br />

Pons Medulla SPINAL MARROW<br />

L/D<br />

R C<br />

M/V<br />

BG TH<br />

HY<br />

T<br />

TG<br />

CB<br />

P M<br />

Major Regions<br />

SP<br />

BG, basal ganglia (cerebral nuclei)<br />

CB, cerebellum<br />

CTX, cerebral cortex (pallium)<br />

HY, hypothalamus<br />

M, medulla<br />

P, pons<br />

SP, spinal cord<br />

T, tectum<br />

TG, tegmentum<br />

TH, thalamus

Cerebral cortex<br />

Anterior<br />

cereb. Optic thal.<br />

gang.<br />

Tuber cinereum<br />

Mid<strong>brain</strong><br />

Cerebellum<br />

Pons Medulla<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Cerebral cortex<br />

Cerebral (central) ganglion<br />

Central tubular gray matter<br />

Spinal cord<br />

Meynert (1872) 23 , Gaskell (1889) 24 , Dejerine and Dejerine-Klumpke (1895) 25<br />

rhinencephalon<br />

rhinencephalon<br />

Late 19th to early 20th century<br />

(modern–h<strong>is</strong>tology)<br />

Cerebellum<br />

corp. Met.<br />

m. quad. RHOMBENCEPH.<br />

thalamus<br />

pars cereb. Pons<br />

p. opt.<br />

Myel.<br />

mam. ped. H T<br />

hypo. hypo.<br />

I S<br />

M U S<br />

H<strong>is</strong> (BNA, 1895) 39<br />

Cerebrum =<br />

fore<strong>brain</strong> + mid<strong>brain</strong><br />

Sulcus limitans<br />

(adds longitudinal organization<br />

to transverse div<strong>is</strong>ions)<br />

sulcus limitans<br />

SPINAL MEDULLA<br />

bas<strong>is</strong><br />

rhinencephalon<br />

tel.<br />

epi.<br />

tectum<br />

teg.<br />

hypothal. S Y<br />

N<br />

d. thalamus<br />

vent. thal.<br />

imp.I S THMUS<br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture V IEWPOINT<br />

Contemporary<br />

Spinal marrow<br />

Bechterew (1900) 30 Carpenter and Sutin (1983) 31 , Nauta and Feirtag (1986) 32 , Williams (1995) 33<br />

Cerebral cortex<br />

Brain stem<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Striate<br />

Optic thal.<br />

corp.<br />

quad.<br />

body<br />

Tuber cinereum<br />

Mid<strong>brain</strong><br />

Pons Medulla<br />

T R U N K<br />

Ann.<br />

Prot.<br />

Herrick (1915) 2<br />

Cerebral cortex Cerebellum<br />

(cortex)<br />

Striate<br />

corp.<br />

m. quad.<br />

thalamus<br />

Pons<br />

pars cereb.<br />

Medulla<br />

body<br />

p. opt. mam.<br />

hypoth. hypo. ped.<br />

p a l l i u m<br />

corpus striatum<br />

striate body<br />

epi.<br />

epi.<br />

Archencephalon<br />

p a l l i u m<br />

bas<strong>is</strong><br />

rhinencephalon<br />

tel.<br />

imp.<br />

epithal.<br />

d. thalamus<br />

vent. thal.<br />

corp.<br />

quad.<br />

Ahlborn (1883) 42 , Kingsbury (1920) 43<br />

Ann.<br />

Prot.<br />

Brain stem<br />

tectum<br />

Met. Myel.<br />

Spinal cord<br />

teg.<br />

hypothal. S Y Deuterencephalon & spinal cord<br />

N<br />

(prechordal)<br />

Palaeëncephalon (old <strong>brain</strong>)<br />

trends in Neurosciences<br />

Neopallium<br />

Archepallium<br />

C E R E B R U M<br />

C E R E B R U M<br />

Spinal cord Brainstem<br />

Spinal cord<br />

p a l l i u m<br />

Cerebellum<br />

Crosby et al. (1962) 40 , Nieuwenhuys et al. (1998) 41<br />

p a l l i u m<br />

rhinencephalon<br />

Edinger (1908) 46 , Kappers (1909) 47 MacLean (1990) 48<br />

p. opt.<br />

hypoth.<br />

Spinal cord<br />

epi.<br />

Met. Myel.<br />

Cerebellum<br />

corp. Met.<br />

m. quad.<br />

thalamus<br />

pars cereb. Pons<br />

p. opt.<br />

Myel.<br />

mam. ped.<br />

hypoth. hypo.<br />

corpus striatum<br />

CB<br />

CB<br />

Fore<strong>brain</strong><br />

Kupffer (1906) 44 , Kuhlenbeck (1967–1978) 45<br />

Mid<strong>brain</strong><br />

Hind<strong>brain</strong><br />

Neomammalian<br />

SPINAL MEDULLA<br />

Paleomammalian<br />

Paleopallium Reptilian<br />

Hox-2.6 (e12.5 mouse)<br />

Wilkinson et al. (1989) 49<br />

TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000 523<br />

Dual <strong>brain</strong><br />

Segmental<br />

Developmental<br />

Genomic Evolutionary

V IEWPOINT<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(d)<br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture<br />

(c)<br />

(e)<br />

hem<strong>is</strong>phere (Table 1). At <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>the</strong> meaning of<br />

‘cerebrum proper’ was being greatly restricted to <strong>the</strong><br />

cerebral hem<strong>is</strong>pheres (Table 1), leading to <strong>the</strong> dem<strong>is</strong>e of<br />

<strong>the</strong> dual <strong>brain</strong> model. As an interesting h<strong>is</strong>torical footnote,<br />

in 1836 Solly60 introduced <strong>the</strong> term ‘hem<strong>is</strong>pheric<br />

ganglion’ to refer to <strong>the</strong> cerebral cortex, in an effort to<br />

provide a complement to Gall and Spurzheim’s ‘great<br />

cerebral ganglion’ (later, <strong>the</strong> basal ganglion).<br />

Segmental models<br />

The evolution of <strong>the</strong>se models – essentially cons<strong>is</strong>ting<br />

of a trunk generating regularly spaced paired<br />

nerves, and suprasegmental cerebrum and cerebellum<br />

– <strong>is</strong> complex and only a broad overview will be given<br />

524 TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000<br />

trends in Neurosciences<br />

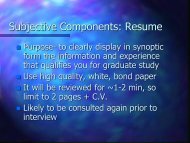

Fig. 3. Pioneering illustrations of CNS topography. (a) In th<strong>is</strong> drawing, Vesalius (1543) 17<br />

illustrates h<strong>is</strong> concept of <strong>the</strong> human dorsal medulla – essentially a trunk that generates a<br />

regular series of paired nerves, beginning rostrally with <strong>the</strong> trigeminal nerves (labeled 3 and 4<br />

at <strong>the</strong> far left) and ending caudally with a 30th pair of spinal nerves at <strong>the</strong> far right. The region<br />

between A and B <strong>is</strong> what we know today as <strong>the</strong> pons and medulla (5 <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> facial nerve; 6 <strong>is</strong><br />

cranial nerves IX–XI; and 7 <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> hypoglossal nerve); that between B and H <strong>is</strong> what we know<br />

as <strong>the</strong> spinal cord. (b) Thirty years later, Varolio 26 illustrated <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> human <strong>brain</strong> and<br />

showed <strong>the</strong> spinal medulla (labeled 1–3 on <strong>the</strong> left side or top; and labeled a,b on <strong>the</strong> right<br />

side or bottom, rostral <strong>is</strong> to <strong>the</strong> left) as extending all <strong>the</strong> way to <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> cerebral hem<strong>is</strong>pheres,<br />

just caudal to what <strong>is</strong> obviously <strong>the</strong> optic chiasm. (c) Shortly <strong>the</strong>reafter, Will<strong>is</strong> 34<br />

extended <strong>the</strong> trunk even far<strong>the</strong>r rostral to include what he identified and named <strong>the</strong> striate<br />

bodies (labeled A in th<strong>is</strong> dorsal view of <strong>the</strong> sheep <strong>brain</strong>, which has been rotated so that rostral<br />

<strong>is</strong> to <strong>the</strong> left). Th<strong>is</strong> figure beautifully illustrates <strong>the</strong> entirety of what Will<strong>is</strong> referred to (leaving<br />

aside <strong>the</strong> cerebellum, T and s, which was b<strong>is</strong>ected and pulled to ei<strong>the</strong>r side) as <strong>the</strong> oblong marrow,<br />

medullary stem, or medullary trunk. (d) A lateral view of <strong>the</strong> right half of a chick embryo<br />

after four days of development as drawn by Malpighi 37 . Using H<strong>is</strong>’s later terminology, <strong>the</strong> following<br />

parts of <strong>the</strong> neural tube seem clear: E indicates <strong>the</strong> paired telencephalic vesicles, D <strong>the</strong><br />

diencephalic vesicle, F <strong>the</strong> optic cup and choroid f<strong>is</strong>sure, A <strong>the</strong> mesencephalic vesicle, B <strong>the</strong><br />

metencephalic vesicle, and C <strong>the</strong> myelencephalic vesicle. (e) Illustration of how Edinger 46<br />

viewed <strong>the</strong> mammalian neëncephalon as being added on top of <strong>the</strong> lower vertebrate paleëncephalon,<br />

basically at <strong>the</strong> rhinal f<strong>is</strong>sure, which extends caudally from <strong>the</strong> olfactory bulb at <strong>the</strong><br />

far left. Some of <strong>the</strong> figures have been lightly retouched so that <strong>the</strong> labels are clearer.<br />

here (Fig. 2). The Vesalian model was refined in <strong>the</strong> late<br />

18th century by Haller18 who divided <strong>the</strong> cerebrum<br />

sequentially into cerebral cortex, striate body, optic<br />

thalamus, and <strong>the</strong> corpora quadrigemini and cerebral<br />

peduncle, which toge<strong>the</strong>r form our mid<strong>brain</strong>. Caudal<br />

to th<strong>is</strong>, he was <strong>the</strong> first to d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>h clearly between<br />

<strong>the</strong> pons and medulla as we now refer to <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

although he was somewhat obscure about <strong>the</strong> larger<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> CNS that <strong>the</strong>y should be placed within. One<br />

of <strong>the</strong> last major anatomical analyses based on <strong>the</strong><br />

Vesalian model was publ<strong>is</strong>hed by Meynert23 in 1872. It<br />

took advantage of <strong>the</strong> h<strong>is</strong>tological methods that had<br />

been introduced earlier in <strong>the</strong> century. Essentially, he<br />

introduced an innovative, longitudinal way of thinking<br />

about <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>stem by dividing <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

posterior cerebral ganglion into a dorsal zone, which<br />

he called <strong>the</strong> optic thalamus proper (our thalamus),<br />

and a ventral zone, <strong>the</strong> tuber cinereum (our hypothalamus).<br />

He included <strong>the</strong> optic thalamus proper and<br />

<strong>the</strong> corpora quadrigemina in <strong>the</strong> true posterior cerebral<br />

ganglion, and included <strong>the</strong> tuber cinereum, cerebral<br />

peduncle (our ventral mid<strong>brain</strong> or tegmentum), pons,<br />

medulla, and spinal cord in what he called <strong>the</strong> central<br />

tubular gray matter, which was responsible for generating<br />

all of <strong>the</strong> motor nerves.<br />

Here, for <strong>the</strong> first time, we can recognize ten basic<br />

parts of <strong>the</strong> CNS that are common to virtually all<br />

modern gross anatomical descriptions: cerebral cortex,<br />

basal ganglia/cerebral nuclei, thalamus and hypothalamus,<br />

tectum and tegmentum, pons, medulla,<br />

cerebellum, and spinal cord (in modern terms).<br />

Will<strong>is</strong>’s basic model of a <strong>brain</strong>stem stretching from<br />

<strong>the</strong> corpus striatum rostrally to <strong>the</strong> medulla caudally<br />

was refined by <strong>the</strong> addition of Haller’s subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions35,36 ,<br />

and in Herrick’s2 final major reincarnation by <strong>the</strong> addition<br />

of H<strong>is</strong>’s embryonic schema (see below).<br />

It <strong>is</strong> Varolio’s basic model that has remained popular<br />

today, refined by div<strong>is</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> central trunk into a<br />

<strong>brain</strong>stem part, generating <strong>the</strong> cranial nerves and a<br />

spinal cord part, generating <strong>the</strong> spinal nerves31,32 . Haller’s<br />

subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>stem have usually been applied<br />

to th<strong>is</strong> model, see for example Ref. 30, although in a<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r idiosyncratic way, Reichert28 and <strong>the</strong>n Schwalbe 29<br />

included <strong>the</strong> cerebellum in <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>stem (Table 1).<br />

Developmental models<br />

The great Baer has <strong>the</strong> d<strong>is</strong>tinction of having provided<br />

simple, descriptive names (Fig. 2) for <strong>the</strong> embryonic<br />

<strong>brain</strong> vesicles first identified by Malpighi (see<br />

above), and for demonstrating 5 that <strong>the</strong>se vesicles are<br />

probably common to all vertebrates. These contributions<br />

have had a profound influence and lasting value.<br />

He recognized three primary vesicles (in Engl<strong>is</strong>h, fore<strong>brain</strong>,<br />

mid<strong>brain</strong> and hind<strong>brain</strong>), and five secondary<br />

vesicles (in Engl<strong>is</strong>h, <strong>the</strong> fore<strong>brain</strong> vesicle divides into<br />

end<strong>brain</strong> and inter<strong>brain</strong> vesicles, and <strong>the</strong> hind<strong>brain</strong><br />

vesicle divides into hind<strong>brain</strong>, cons<strong>is</strong>ting of cerebellum<br />

and pons and after<strong>brain</strong> vesicles). The actual subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions<br />

were quite similar to Haller’s scheme, proposed<br />

a few years earlier, so a number of equivalent<br />

synonyms were generated, for example, optic thalamus<br />

and inter<strong>brain</strong>, and end<strong>brain</strong> and cerebrum<br />

(Fig. 2). By <strong>the</strong> mid-19th century, writers using <strong>the</strong><br />

dual <strong>brain</strong>, segmental, and developmental models of<br />

CNS organization were using each o<strong>the</strong>rs nomenclature<br />

for subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions almost interchangeably. <strong>What</strong><br />

was different was <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong>y grouped <strong>the</strong> various

TABLE 1. H<strong>is</strong>torical overview of <strong>the</strong> meaning of some common gross anatomical terms for parts of <strong>the</strong> CNS<br />

Common gross Modern scheme of basic subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions Selected refs<br />

anatomical terms<br />

Cerebral Basal Inter- Mid- Hind- Cere- Spinal<br />

cortex ganglia <strong>brain</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>brain</strong> bellum cord<br />

subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions. The Malpighi–Baer model was unique<br />

because it viewed <strong>the</strong> basic plan of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong> in terms<br />

of three rostrocaudally arranged swellings, in contrast<br />

to suprasegmental cerebrum and cerebellum attached<br />

to a trunk generating <strong>the</strong> cranial and spinal nerves.<br />

The final major variation of <strong>the</strong> Malpighi–Baer<br />

model was provided by H<strong>is</strong> towards <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong><br />

19th century. He described 61 a longitudinally oriented<br />

limiting sulcus that divides <strong>the</strong> right and left halves of<br />

<strong>the</strong> developing neural tube into a dorsal alar plate<br />

(which, at least initially, <strong>is</strong> sensory in function) and a<br />

ventral basal plate (which, at least initially, <strong>is</strong> motor in<br />

function). Subsequently, <strong>the</strong> question of where to<br />

place <strong>the</strong> rostral end of <strong>the</strong> limiting sulcus has generated<br />

endless and unresolved controversy, although<br />

H<strong>is</strong> himself placed it at <strong>the</strong> optic chiasm in <strong>the</strong> 1895<br />

‘Basle Nomina Anatomica’ (BNA), an ‘official’ tabulation<br />

of anatomical nomenclature 39,62 . In some ways<br />

<strong>the</strong> original BNA taxonomy of <strong>brain</strong> parts <strong>is</strong> less sat<strong>is</strong>factory<br />

today than <strong>the</strong> older and simpler scheme of<br />

Baer. For example, H<strong>is</strong> divided <strong>the</strong> end<strong>brain</strong> (telencephalic)<br />

vesicle into pallium, rhinencephalon, and<br />

corpus striatum, <strong>the</strong> latter of which he extended to<br />

include all of <strong>the</strong> hypothalamus except for <strong>the</strong> mammillary<br />

bodies (even though <strong>the</strong> hypothalamus,<br />

including <strong>the</strong> preoptic region, <strong>is</strong> derived from <strong>the</strong><br />

third ventricle neuroepi<strong>the</strong>lium). In addition, H<strong>is</strong><br />

included, between <strong>the</strong> mid<strong>brain</strong> and hind<strong>brain</strong>, a narrow<br />

<strong>is</strong>thmus vesicle whose components in <strong>the</strong> adult<br />

mammal have never been identified sat<strong>is</strong>factorily.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, H<strong>is</strong>’s basic model has had a profound<br />

and lasting influence, see for example Ref. 41, mainly<br />

because it makes a d<strong>is</strong>tinction between dorsal, sensory<br />

regions of <strong>the</strong> CNS and ventral, motor regions.<br />

Analys<strong>is</strong> of th<strong>is</strong> combined structural and functional<br />

approach would require ano<strong>the</strong>r essay, but by way of<br />

introduction it very nicely complemented <strong>the</strong> brilliant<br />

earlier work of Magendie 63 and of Luys 22 and<br />

Meynert 23 . Magendie showed experimentally that <strong>the</strong><br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture V IEWPOINT<br />

Cerebrum (proper) X X X X X Ar<strong>is</strong>totle10 , Vieussens 13 1684, Monro 14 1783, Reil 15 1809<br />

X X X X Vesalius17 1543, H<strong>is</strong> 39 (BNA 1895), Herrick 2 1915<br />

X X X Müller54 1843<br />

X X Varolio26 1573, Reichert 28 1859, Nauta-Feirtig 32 1986<br />

X Will<strong>is</strong>34 1664, Ferrier 36 1876<br />

Cerebral hem<strong>is</strong>phere X X Baer 5 1828, Herrick 2 1915, Nauta-Feirtig 32 1986<br />

X Will<strong>is</strong>34 1664, Ferrier 36 1876<br />

Cerebral or basal X X X X Vieussens 13 1684, Reil 15 1809, Gall-Spurzheim 16 1810<br />

nuclei or ganglia X X X Meynert23 1872<br />

X X Ferrier36 1876<br />

X Herrick2 1915, Crosby et al. 40 1962, Nauta-Feirtig 32 1986<br />

Cerebellum X Ar<strong>is</strong>totle 10 , universal since antiquity<br />

Brainstem X X X X Baer 5 1828, Herrick 2 1915, Ranson-Clark 55 1959<br />

X X X Obersteiner56 1888, Carpenter-Sutin 31 1983, Nauta-Feirtig 32 1986<br />

X X X X Reichert28 1859, Schwalbe 29 1881<br />

X X Jacobsohn57 1909, Olszewski-Baxter 58 1954, Williams 33 1995<br />

Spinal cord X X X X Varolio 26 1573, Aranzi 27 1587<br />

X X Vesalius17 1543, Malpighi 37 1672<br />

X Ar<strong>is</strong>totle 10 , universal since 18th century<br />

dorsal roots carry sensory information into <strong>the</strong> spinal<br />

cord, whereas <strong>the</strong> ventral roots carry motor information<br />

out of <strong>the</strong> spinal cord. Luys and Meynert<br />

suggested that sensory information travels up dorsal<br />

regions of <strong>the</strong> neurax<strong>is</strong> on route to <strong>the</strong> cerebral<br />

hem<strong>is</strong>pheres, whereas motor information leaving <strong>the</strong><br />

hem<strong>is</strong>pheres takes a more ventral route.<br />

A clear alternative to <strong>the</strong> Malpighi–Baer model was<br />

proposed by Ahlborn in 1883 (Ref. 42). Based on an<br />

examination of lamprey development, he proposed<br />

that <strong>the</strong> hind<strong>brain</strong>, similar to <strong>the</strong> spinal cord, develops<br />

adjacent to <strong>the</strong> notochord and <strong>is</strong> thus epichordal,<br />

whereas <strong>the</strong> fore<strong>brain</strong> and mid<strong>brain</strong> (Vesalius’s cerebrum)<br />

develop rostral to <strong>the</strong> notochord and are thus<br />

prechordal. Th<strong>is</strong> idea was supported by Kingsbury43 ,<br />

who showed conclusively that <strong>the</strong> definitive, h<strong>is</strong>tologically<br />

defined embryonic floor plate does not extend rostral<br />

to <strong>the</strong> hind<strong>brain</strong>–mid<strong>brain</strong> junction. Assuming that<br />

<strong>the</strong> notochord and floor plate are essentially co-extensive,<br />

th<strong>is</strong> would support a prechordal derivation of <strong>the</strong><br />

mid<strong>brain</strong> and fore<strong>brain</strong>. By contrast, Kupffer publ<strong>is</strong>hed<br />

an exhaustive review of h<strong>is</strong> own work and that of<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs in 1906 (Ref. 44), concluding that <strong>the</strong> mid<strong>brain</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong> epichordal. He used <strong>the</strong> terms deuterencephalon for<br />

supposed epichordal parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>, and archencephalon<br />

for supposed prechordal parts, an interpretation<br />

that has been followed by Kuhlenbeck45 .<br />

Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong> exact rostral limit of <strong>the</strong> notochord<br />

and its precursor remains problematic, partly because of<br />

<strong>the</strong> uncertain nature of <strong>the</strong> so-called prechordal plate.<br />

Evolutionary models<br />

All of <strong>the</strong> models d<strong>is</strong>cussed so far are based on comparative<br />

anatomy and embryology, with an emphas<strong>is</strong><br />

on mammals, and even humans. However, it was<br />

inevitable that phylogenetic models would be proposed<br />

after <strong>the</strong> publication of Darwin’s The Origin of<br />

Species in 1859 (Ref. 64). Interestingly, <strong>the</strong>y did not<br />

appear until approximately <strong>the</strong> turn of <strong>the</strong> century,<br />

TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000 525

V IEWPOINT<br />

L.W. Swanson – Brain architecture<br />

and <strong>the</strong>n had only a brief, d<strong>is</strong>ruptive life, undoubtedly<br />

because relatively small amounts of reliable information<br />

about non-mammalian <strong>brain</strong> circuitry were<br />

(and are) available. In spite of th<strong>is</strong>, <strong>the</strong> main intellectual<br />

stimulus came from Edinger (see Ref. 46), who<br />

proposed a d<strong>is</strong>tinction between palaeëncephalon (old<br />

<strong>brain</strong>) and neëncephalon (new <strong>brain</strong>). According to<br />

th<strong>is</strong> model (Figs 2,3), part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong> <strong>is</strong> common to<br />

and essentially unchanged throughout all vertebrates,<br />

and <strong>is</strong> responsible for all of <strong>the</strong> sensory–motor reflexes<br />

and purely instinctive behaviors necessary for survival.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> palaeëncephalon, which constitutes<br />

<strong>the</strong> entire f<strong>is</strong>h <strong>brain</strong>. During <strong>the</strong> course of subsequent<br />

evolution, a new layer <strong>is</strong> added, <strong>the</strong> neëncephalon,<br />

which corresponds to <strong>the</strong> cerebral pallium. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> tiny<br />

in amphibians, a little bigger in reptiles, considerably<br />

larger in birds and huge in mammals. According to<br />

th<strong>is</strong> model, <strong>brain</strong> evolution took place in a geological<br />

fashion by <strong>the</strong> addition of strata.<br />

Edinger’s young colleague, Kappers, soon elaborated<br />

th<strong>is</strong> basic idea dividing <strong>the</strong> pallium into three successively<br />

evolved regions47 : <strong>the</strong> oldest or paleopallium<br />

(essentially <strong>the</strong> primary olfactory cortex), archipallium<br />

(more or less Ammon’s horn or <strong>the</strong> hippocampus), and<br />

neopallium (all <strong>the</strong> rest, Fig. 2). In addition, he divided<br />

<strong>the</strong> corpus striatum (basal ganglia/cerebral nuclei) into<br />

three parts: <strong>the</strong> paleostri-atum (globus pallidus), arch<strong>is</strong>triatum<br />

(amygdala), and neostriatum (caudate nucleus<br />

and putamen) 65 . Omitting details, th<strong>is</strong> line of thinking<br />

led to designations like paleo-, archi- and neothalamus;<br />

and paleo-, archi- and neocerebellum (see Ref. 45). It<br />

has had very little influence on contemporary neuroscience<br />

and <strong>the</strong> basic connectional principles that it<br />

rested on almost a century ago have not been borne<br />

out (for example, that almost all sensory inputs to <strong>the</strong><br />

pallium of f<strong>is</strong>h and amphibians are inevitably olfactory)<br />

41,45 . Instead, most contemporary evolutionary (i.e.<br />

comparative) thinking seems to be based on <strong>the</strong> embryological<br />

models d<strong>is</strong>cussed above (see Refs 41,45). All<br />

that remain of th<strong>is</strong> model (except for MacLean’s triune<br />

<strong>brain</strong> concept48 ; Fig. 2) are <strong>the</strong> constantly used, basically<br />

inaccurate, terms neocortex and neostriatum. It <strong>is</strong><br />

telling that Elliot Smith, who actually introduced <strong>the</strong><br />

concept of ‘neopallium’ in 1901 (Ref. 66), wrote a strenuous<br />

d<strong>is</strong>claimer less than a decade later67 .<br />

Genomic models<br />

Molecular genetics <strong>is</strong> breathing new life into developmental<br />

and evolutionary models of <strong>brain</strong> organization,<br />

although it <strong>is</strong> premature to start placing <strong>the</strong> results into<br />

a h<strong>is</strong>torical perspective. The ultimate goal <strong>is</strong> to decipher<br />

and understand <strong>the</strong> genetic program that assembles <strong>the</strong><br />

neural tube, in part by analysing spatiotemporal patterns<br />

of gene expression throughout development and<br />

establ<strong>is</strong>hing <strong>the</strong>ir functional significance. Once important<br />

sets of genes are identified, <strong>the</strong>ir expression patterns<br />

could be compared to <strong>the</strong> many structural patterns illustrated<br />

in Fig. 2, and eventually th<strong>is</strong> approach should<br />

provide criteria for helping to decide which, if any, of<br />

<strong>the</strong> many structural arrangements suggested thus far<br />

best represent <strong>the</strong> basic plan of <strong>the</strong> CNS (Ref. 68).<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, it might be possible to infer how <strong>the</strong>se<br />

genomic programs, with <strong>the</strong>ir constituent genes,<br />

evolved over <strong>the</strong> ~400 million years of vertebrate ex<strong>is</strong>tence<br />

69 – and perhaps to determine whe<strong>the</strong>r 19th-century<br />

attempts (see Ref. 24) to homologize <strong>the</strong> invertebrate<br />

and vertebrate CNSs have any validity 70 . To date, <strong>the</strong><br />

526 TINS Vol. 23, No. 11, 2000<br />

best example by far of th<strong>is</strong> approach <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> partly overlapping<br />

patterns of Hox gene expression in <strong>the</strong> developing<br />

vertebrate hind<strong>brain</strong>49 , where <strong>the</strong>y correlate to <strong>the</strong><br />

appearance of <strong>the</strong> long-known finer subdiv<strong>is</strong>ions called<br />

rhombomeres (see Ref. 45).<br />

Overview<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> review has focused narrowly on <strong>the</strong> h<strong>is</strong>tory of<br />

attempts to enumerate <strong>the</strong> major parts of <strong>the</strong> adult<br />

vertebrate CNS – an exerc<strong>is</strong>e in classical regional or<br />

topographic structural analys<strong>is</strong>, identical to enumerating<br />

<strong>the</strong> major parts of <strong>the</strong> body: head, neck, trunk, tail,<br />

upper limbs and lower limbs. The conclusion seems to<br />

be that <strong>the</strong>re are at least ten basic parts that, after centuries<br />

of research, almost everyone now agrees on<br />

(ignoring d<strong>is</strong>putes about exactly what <strong>the</strong>y are called,<br />

and where <strong>the</strong>ir borders are placed): (1) a dorsal cerebral<br />

cortex or pallium; (2) ventral or basal cerebral<br />

nuclei or ‘ganglia’ [(1) and (2) forming <strong>the</strong> cerebral<br />

hem<strong>is</strong>pheres or cerebrum]; (3) a dorsal thalamus; (4) a<br />

ventral hypothalamus [(3) and (4) forming <strong>the</strong> inter<strong>brain</strong>],<br />

(5) a dorsal tectum, (6) a ventral tegmentum<br />

[(5) and (6) forming <strong>the</strong> mid<strong>brain</strong>], (7) a cerebellum,<br />

(8) a pons, (9) a medulla, and (10) a spinal cord.<br />

By contrast, <strong>the</strong>re are at least five different <strong>the</strong>oretical<br />

frameworks for grouping or arranging <strong>the</strong>se ten<br />

basic parts (and many more variations on <strong>the</strong> basic<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes; Fig. 2), and it <strong>is</strong> doubtful that <strong>the</strong>re are compelling<br />

reasons at th<strong>is</strong> stage for adopting one particular<br />

scheme. Therefore, <strong>the</strong> time does not seem ripe to<br />

propose here yet ano<strong>the</strong>r unifying hypo<strong>the</strong>s<strong>is</strong> or<br />

model based on essentially <strong>the</strong> same data.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, it <strong>is</strong> worth observing that <strong>the</strong>re have<br />

been no serious attempts to present a comprehensive,<br />

modern systems model of CNS organization.<br />

Reconsidering <strong>the</strong> gross anatomy analogy, <strong>the</strong><br />

regional account <strong>is</strong> traditionally complemented with a<br />

systems account. Thus, in addition to <strong>the</strong> various<br />

topographically arranged parts or regions l<strong>is</strong>ted above,<br />

<strong>the</strong> body <strong>is</strong> described as having skeletomotor, circulatory,<br />

digestive, respiratory, reproductive, immune,<br />

endocrine and nervous systems. One’s initial thought<br />

might be that <strong>the</strong> systems approach <strong>is</strong> more useful<br />

than <strong>the</strong> topographic, but from a broad functional<br />

perspective th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> not strictly true. The hand <strong>is</strong> used,<br />

for example, to write with. For <strong>the</strong> upper limb to perform<br />

th<strong>is</strong> behavior <strong>the</strong> skeletal system acts as a series<br />

of levers that are moved by <strong>the</strong> muscles, which in turn<br />

are controlled by nerves directed from <strong>the</strong> CNS. The<br />

vascular system supplies oxygen and nutrients to <strong>the</strong><br />

t<strong>is</strong>sues in <strong>the</strong> limb, <strong>the</strong> immune system fights infections<br />

in th<strong>is</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> body, etc. One important reason<br />

why <strong>the</strong> basic organization of <strong>the</strong> nervous system<br />

remains mysterious <strong>is</strong> that a consensus enumeration<br />

of its functional systems has not been achieved.<br />

Ultimately, a profound understanding of what <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>brain</strong> <strong>is</strong> and how <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong> works will be based on an<br />

integrated view of its topographic and systems organization.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> has been accompl<strong>is</strong>hed for most of <strong>the</strong><br />

body, partly explaining why <strong>the</strong> reduction<strong>is</strong>tic molecular<br />

biology approach <strong>is</strong> so powerful. However, <strong>the</strong><br />

nervous system remains problematic: <strong>the</strong> nature of its<br />

organizing principles as a system <strong>is</strong> an unsolved problem<br />

that can only hinder <strong>the</strong> rational search for ways<br />

to cure <strong>the</strong> many d<strong>is</strong>eases that strike within it.<br />

Finally, note in Fig. 2 that <strong>the</strong> tripartite model first<br />

proposed by Varolio in 1573 remains <strong>the</strong> simplest for

mammals, refined only by a subdiv<strong>is</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> central<br />

trunk into <strong>brain</strong>stem and spinal cord. Perhaps a systems<br />

model based on <strong>the</strong> fundamental organization of<br />

connections within and between <strong>the</strong>se three parts<br />

might be a useful way to start. The profound question<br />

really <strong>is</strong> not ‘what <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>brain</strong>?’ but ra<strong>the</strong>r ‘what are<br />

<strong>the</strong> basic parts of <strong>the</strong> nervous system and how are <strong>the</strong>y<br />

interconnected functionally?’<br />

Selected references<br />

1 Scherz, G. (1965) Nicolaus Steno’s Lecture on <strong>the</strong> Anatomy of <strong>the</strong><br />

Brain, Busck<br />

2 Herrick, C.J. (1915) An Introduction to Neurology, Saunders<br />

3 Swanson, L.W. and Petrovich, G. (1998) <strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> amygdala?<br />

Trends Neurosci. 28, 323–331<br />

4 Anthoney, T.R. (1994) Neuroanatomy and <strong>the</strong> Neurologic Exam: A<br />

Thesaurus of Synonyms, Similar-Sounding Non–Synonyms, and Terms<br />

of Variable Meaning, CRC Press<br />

5 Baer, K.E.v. (1828–37) Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere.<br />

Beobachtung und Reflexion, Bornträger. See <strong>the</strong> facsimile reprint<br />

publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1967 by Impression Anastaltique Culture et Civil<strong>is</strong>ation<br />

6 Walker, A.E. (1998) The Genes<strong>is</strong> of Neuroscience, American<br />

Association of Neurological Surgeons<br />

7 Breasted, J.H. (1930) The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, Chicago<br />

8 McHenry, L.C. (1969) Garr<strong>is</strong>on’s H<strong>is</strong>tory of Neurology, Thomas<br />

9 Finger, S. (1994) Origins of Neuroscience: A H<strong>is</strong>tory of Explorations<br />

into Brain Function, Oxford<br />

10 Clarke, E. and O’Malley, C.D. (1996) The Human Brain and Spinal<br />

Cord: A H<strong>is</strong>torical Study Illustrated by Writings from Antiquity to <strong>the</strong><br />

Twentieth Century, Norman<br />

11 Berengario da Carpi, J. (1523) Isagogae breves, Benedictum Hector<strong>is</strong>.<br />

See Engl<strong>is</strong>h translation by L.R. Lind publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1969 by Kraus<br />

12 Dryander, J. (1536) Anatomia Capit<strong>is</strong> Humani. See Engl<strong>is</strong>h<br />

translation in Lind, L.R. (1975) Studies in Pre-Vesalian Anatomy:<br />

Biography, Translations, Documents, pp. 299–303, American<br />

Philosophical Society<br />

13 Vieussens, R. (1684) Neurographica Universal<strong>is</strong>, Certe<br />

14 Monro, A. (1783) Observations on <strong>the</strong> Structure and Functions of <strong>the</strong><br />

Nervous System, Creech<br />

15 Reil, J.C. (1809) Untersuchungen über den Bau des grossen<br />

Gehirns im Menschen. Arch. Physiol. Halle 9, 136–195. See rough<br />

Engl<strong>is</strong>h translation in facsimile reprint of H. Mayo (1822–1823)<br />

Anatomical and Physiological Commentaries publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1985 by<br />

The Classics of Neurology & Neurosurgery Library<br />

16 Gall, F.J. and Spurzheim, J.C. (1810–1819) Anatomie et physiologie<br />

du système nerveux en général et du cerveau in particulier, Vols 1–4<br />

and Atlas, Schoell<br />

17 Singer, C. (1952) Vesalius on <strong>the</strong> Human Brain: Introduction,<br />

Translation of Text, Translation of Descriptions of Figures, Notes to <strong>the</strong><br />

Translations, Figures, Oxford<br />

18 Haller, A. von (1781–2) Iconum anatomiarum..., Fasciculus VII...,<br />

Vandenhoeckii<br />

19 Bell, C. (1802) The Anatomy of <strong>the</strong> Brain, Explained in a Series of<br />

Engravings, Longman, Rees, Cadell and Davies. See facsimile<br />

reprint publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1982 by Classics of Medicine Library<br />

20 Leuret, F. and Gratiolet, P.L. (1839–1857) Anatomie Comparée du<br />

Système Nerveux, Considéré dans ses Rapports avec l’Intelligence, Baillière<br />

21 Kölliker, A. (1854) Manual of Human Microscopal Anatomy, Lippencott<br />

22 Luys, J.B. (1865) Recherches sur le Système Nerveux Cérébro–Spinal:<br />

sa Structure, ses Fonctions et ses Maladies, Baillière<br />

23 Meynert, T. (1872) The <strong>brain</strong> of mammals. In A Manual of H<strong>is</strong>tology<br />

(Stricker, S., ed.), pp. 650–766, Wood<br />

24 Gaskell, W.H. (1889) On <strong>the</strong> relation between <strong>the</strong> structure,<br />

function, d<strong>is</strong>tribution and origin of <strong>the</strong> cranial nerves; toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

with a <strong>the</strong>ory of <strong>the</strong> origin of <strong>the</strong> nervous system of vertebrata.<br />

J. Physiol. London 10, 153–211<br />

25 Dejerine, J.J. and Dejerine-Klumke, A.M. (1895–1901) Anatomie<br />

des Centres Nerveux, Rueff<br />

26 Varolio, C. (1573) Anatomiae Sive de Resolutione Corpor<strong>is</strong> Humani<br />

Libri 4. See facsimile reprint publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1969 by Impression<br />

Anastaltique Culture et Civil<strong>is</strong>ation<br />

27 Aranzi, G.C. (1587) De Humano Foetu Liber Tertio Editus, ac<br />

Recognitus, Brechtanus<br />

28 Reichert, K.B. (1859–1861) Der Bau des menschlichen Gehirns durch<br />

Abbildungen mit Erlauterndem Texte, Engelmann<br />

29 Schwalbe, G.A. (1881) Lehrbuch der Neurologie, Besold<br />

30 Bechterew, W.v. (1900) Les Voies de Conduction de Cerveau et de la<br />

Moelle, Maloine<br />

31 Carpenter, M.B. and Sutin, J. (1983) Human Neuroanatomy, 8th<br />

edn, Williams & Wilkins<br />