13th Annual International Management Conference Proceeding

13th Annual International Management Conference Proceeding

13th Annual International Management Conference Proceeding

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Gender diversity on the Board, Intellectual capital, Governance Mechanisms and corporate performance: a Theoretical<br />

Configuration<br />

Nkundabanyanga K Stephen,<br />

Makerere University Business school<br />

Email: snkundabanyanga@mubs.ac.ug<br />

sknkunda@yahoo.com<br />

Dr. Ntayi M. Joseph,<br />

Makerere University Business School<br />

Email: ntayius@yahoo.com<br />

jntayi@mubs.ac.ug<br />

Mr. Sserwanga Arthur<br />

Makerere University Business School<br />

Email: asserwanga@yahoo.com<br />

asserwanga@mubs.ac.ug<br />

21st November 2006<br />

Abstract<br />

Several theories, most notably agency, resource-dependency, institutional and social network theories have been put<br />

forward to explain and predict the attributes of boards and how these in turn affect corporate performance. While<br />

these theories have all been applied to the board phenomenon, I argue that their failure to incorporate intellectual capital<br />

and gender diversity on the board of directors explicitly, renders them ineffectual in today’s knowledge economy. I<br />

contend that corporate performance predictive validity of these theories is contingent upon the existence of appropriate<br />

intellectual capital and gender diversity on the board. This paper presents a critical review of the above theories and<br />

proposes a comprehensive framework for predicting the attributes of boards and firm performance<br />

Introduction<br />

Several theories, most notably agency, resource-dependency, institutional and social network theories have been<br />

put forward to explain and predict the attributes of boards and how these in turn affect corporate performance.<br />

While these theories have all been applied to the board phenomenon, we argue that their failure to incorporate<br />

intellectual capital and gender diversity on the board of directors explicitly, renders them ineffectual in today’s<br />

knowledge economy. We contend that these theories’ corporate performance predictive validity is contingent upon the<br />

existence of appropriate intellectual capital and gender diversity on the board. In the next section, we present a<br />

theoretical/empirical review and hypotheses and argue that these theories are inadequate in explaining performance of<br />

firms. We propose a theoretical framework and finally we end with theoretical and methodological implications.<br />

Theoretical review<br />

Agency theory<br />

Since Berle and Means (1932), a great deal of effort has been made on this theory and it has been the central issue in<br />

corporate governance debate for the last two decades. Most of the literature argues that some governance mechanisms by<br />

outside investors (in particular shareholders) are necessary to discipline management behavior. These mechanisms draw<br />

heavily from agency theory, which assumes that managers’ own interests submit to constraints imposed by the agency<br />

relationship. Thus, boards of directors are put in place to monitor management on behalf of shareholders (Eisenhardt,<br />

1989; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). We find this standard view unsatisfactory, since it ignores an implicit control<br />

mechanism of managers inside the firm, gender diversity on the boards, pre-nomination discussions and post-nomination<br />

evaluations of directors and a particular manager’s risk perception (which affects a Manager’s strategic choices) and<br />

focuses on exogenous controls to management.<br />

Outside the standard agency paradigm, some researchers suggest that managers are controlled more or less inside the firm<br />

(Sunder, 1997; Donaldson and Lorsch 1983) to the extent they are primarily concerned with firm performance proxied<br />

by long-term corporate survival. Shareholders concentrate on external control because of the need to solve the agency<br />

problems like the moral hazard, introduced by three assumptions of agency. The first assumption is that agents are selfinterested;<br />

which is illustrated by an agent choosing actions to maximize utility and is assumed to be effort averse. Real<br />

life situations illustrate this postulation by on-the-job consumption, shirking and pursuing off-the job opportunities<br />

1

(Kunz and Pfaff, 2002). The second assumption concerns attitude towards risk. Whereas the principal is considered risk<br />

neutral, agents are considered risk averse. Therefore, the agent will require additional compensation in the form of risk<br />

premium, for taking risks of the principal. The third assumption concerns the information asymmetry. The agent<br />

possesses hush-hush information that is not necessarily available to the principal free of charge. Consequently, the<br />

principal has limited information on the actions of the agent, her actual level of effort and the state of nature.<br />

By concentrating on outside control mechanisms, the agency theory fails to acknowledge that insider control mechanisms<br />

prevents managers’ moral hazard and makes it possible that the firm continues to survive for a long period. By<br />

overlooking the possibility that the degree of the manager’s survival motive may depend on the firm’s domestic (such as<br />

information sharing between the manager and workers) and exterior (such as labor market rigidity) factors, the agency<br />

theory does not explain (i) why corporate managers tend to pursue the survival of the firm, (ii) what factors affect the<br />

manager’s survival motive, and (iii) how the survival motive affects shareholders’ wealth.<br />

Even if managers were constrained by the agency relationship in their actions, their separation from ownership provides<br />

the opportunity for them (agents) to act in their own self-interest by maximizing their own wealth and power at the<br />

expense of the owners (principals) (Fama, 1980; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). For this, the agency theory only succeeds in<br />

explaining partially why companies make decisions, which do not always conform to the expectations of maximizing<br />

shareholder wealth, secondly, why directors have an interest in changing accounting standards as standards affect the<br />

calculation of profit, which in turn influences the directors’ remuneration, and also why directors engage in creative<br />

accounting practices. The theory tends to focus on what the manager is likely to do and fails to recognize the processes<br />

through which the manager’s roles are performed to the extent he/she may exhibit dysfunctional behavior. This<br />

dysfunctional behaviour by the agent means that the profit aimed for will not be maximum profit, because of the<br />

directors’ wishes for expenditure on themselves, their staff and the perquisites of management. This oversight tempts an<br />

argument that the agency theory may not be robust in explaining performance of firms. One particular criticism in this<br />

regard is that the role of intellectual capital of firms and pre –nomination discussions and post-nomination evaluations<br />

of directors and CEO celebrity so far, has not been adequately stressed by the agency theory. Given the growing<br />

importance of intellectual capital in today’s knowledge economy, we criticize the theory for insufficient realism based on<br />

the growing importance of intellectual capital and negotiation skills (as implied by pre-nomination discussions and post<br />

nomination evaluations and CEO celebrity). CEO celebrity arises for instance when journalists broadcast the attribution<br />

that a firm’s performance has been caused by its CEO’s actions (Mathew, Violina and Timothy, 2004).<br />

Finally, Agency theory acknowledges that boards will vary in their incentives to monitor on behalf of shareholders and<br />

as a result, incentives are an important precursor to effective monitoring (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling,<br />

1976). However, the theory does not adequately address this issue, it just acknowledges. In particular, how does for<br />

example diversity of gender on corporate boards count on the board-monitoring role? There is evidence (Westphal &<br />

Milton, 2000) that the composition of boards should not be overly homogeneous. One particular aspect of this<br />

diversity could be a particular director’s risk perception and gender. This appears to point at the role of<br />

entrepreneurship and gender diversity on the boards. We notice that since in real world there is no perfect market of<br />

information, the intrapreneurs’ ability to win is helped by superior knowledge and experience acquired over time<br />

(Corley, 1990), which is an apparent reference to intellectual capital. Agency theorists (e.g. Baysinger & Butler, 1985;<br />

Daily & Dalton, 1994a, 1994b; Weisbach, 1988) acknowledge that board independence, or the degree to which board<br />

members are dependent on the current CEO or organization, is seen as a primary incentive that is key to board<br />

monitoring. However this dependence my be inevitable since an individual board member could have unique<br />

capabilities. The theory therefore lacks credence by ignoring that the board needs some independence even from a<br />

shareholder (principal). The contrast between agency theory’s strong theoretical logic and widespread policy influence<br />

on board phenomena vis-`avis its inconclusive empirical record has prompted scholars to search for alternative theories,<br />

which we turn to next.<br />

Resource-dependency theory<br />

Resource-dependence theory views board directors as “boundary spanners” who extract resources from the environment<br />

(Pfeffer, 1972). It predicts that the more resource-rich outside directors are on the board to help bring in needed<br />

resources, the better the firm performance. Resource-based theory views firms as collections of productive tangible and<br />

intangible capital resources that can be combined to derive new products and services (Wernerfelt, 1984). Though this<br />

theory does not directly deal with weaknesses of the agency theory, it tries to focus marginally on intellectual capital<br />

resources. Key among these resources is the firm’s knowledge and relationship assets. Relationship-based assets provide<br />

access to other resources such as complementary knowledge and other tangible resources that the firm can combine with<br />

2

its own. Relationship-based assets can exist at various levels: with customers, with partners, and with suppliers. However,<br />

Penrose (1959) recognized over four decades ago that it is not the firm’s resources but the services that those resources<br />

render that are of value to the firm.<br />

Nowadays the dominant view of business strategy –resource-based view of firms – is based on the concept of economic<br />

rent and the view of the company as a collection of capabilities. This view of strategy has a coherence and integrative role<br />

that places it well ahead of other mechanisms of strategic decision-making (Kay, 2003). The resource-based perspective<br />

highlights the need for a fit between the external market context in which a company operates and its internal<br />

capabilities. It is grounded in the perspective that a firm's internal environment, in terms of its resources and capabilities,<br />

is more critical to the determination of strategic action than is the external environment. Instead of focusing on the<br />

accumulation of resources necessary to implement the strategy dictated by conditions and constraints in the external<br />

environment (input/output model), the resource-based view suggests that a firm's unique resources and capabilities<br />

provide the basis for a strategy. The strategy chosen should allow the firm to best exploit its core competencies relative<br />

to opportunities in the external environment (Hitt, Ireland, & Hoskisson, 2001).<br />

The drawback with resource-dependency theory is that it does not fully explain corporate (firm) performance. We<br />

contend that the resource-based view is not firmly established, its application is perceptive and its Concepts are<br />

unsettled. First, there are certain assumptions; that resources are diversely distributed across competing firms and<br />

resources are imperfectly mobile with the four attributes: value (productivity) resource, rareness, imperfect imitability,<br />

and nonsubstitutability (Barney, 1991). In addition, Peteraf (1993) presents four conditions in which resourcedependency<br />

theory can generate superior firm performance: superior resources (heterogeneity within an industry), ex<br />

post limits to competition, imperfect resource mobility, and ex ante limits to competition, all of which must be met in<br />

order to generate superior performance. The resource-dependency theory cannot always allow firms to generate superior<br />

performance based on the existing assumptions and conditions due to the dynamic characteristics of the current market<br />

environment in which consumers taste, preferences, and behaviors are always changing together with the offerings of<br />

suppliers’ resources (Dickson, 1996). Human resources, for example, cannot be taken to be immobile in this respect.<br />

Even then, other critics (Drejer, 2000; Wade & Hulland, 2004) have posited that the assumption of perfect imitability<br />

promotes ambiguity leading to a conclusion that firms are static which overlooks their desire to develop an arsenal of<br />

intellectual capital resources overtime. This perfect imitability assumption is difficult to sustain in this era of<br />

information technology where firms are always in search of intellectual capital resources to sustain superior<br />

performance.<br />

Institutional theory<br />

The past two decades have seen a major reassertion of institutional theories in social sciences and beyond (Guy, 2000).<br />

The March and Olsen (1984) article in the APSR cited by Guy, 2000 was the beginning of the insurrection against the<br />

methodological uniqueness of both behaviorism and rational choice approaches. Although a proliferation and<br />

application of institutional theories can be traced back from March and Olsen (1989; 1994; Brunsson and Olsen, 1993;<br />

Olsen and Peters, 1996), Sociologists like DiMaggio and Powell, 1991; and Scott, 1995; Zucker, 1987 have resurrected<br />

institutional approaches to the basic questions in this discipline. While this proliferation is gratifying to those who never<br />

give up on this theory, we argue that this theory ignores voluntary disclosure of information and therefore the signaling<br />

effect of such information. In fact, Stigler (1964a, 1664b) and subsequently Benston (1982a, 1982b) question the<br />

necessity and efficacy of continuous disclosure as advocated by shareholders. Developing the socio-cognitive perspective<br />

in their study, Carpenter and Westphal (2001) note that individuals cope with complex decision- making tasks by<br />

relying on the knowledge structures they have developed about their environment and from experience in similar roles.<br />

Accordingly, they argue, directors are likely to use knowledge structures developed from their experience on other boards<br />

and to learn about business practices through their social interaction and communication with other directors in board<br />

and committee meetings, as board members evaluate management and raise ideas and suggestions for better strategy<br />

implementation. Information acquired from fellow directors may be particularly influential because it often comes from<br />

a trusted source and is typically more timely and current than that derived from secondary sources. While the focus of<br />

Dimaggio & Powell (1991) is the homogenization that emerges out of institutional isomorphism, this observation does<br />

not blend well with institutional theorists. This is because these social connections and opportunities for vicarious<br />

learning can lead to more highly developed knowledge structures for implementing strategy. Recent academicians<br />

notably Williams (2001) have concluded that to maintain any superior performance it has, a firm could reduce the<br />

intellectual capital disclosure levels in an effort not to signal competitors and others as to where potential opportunities<br />

may lie.<br />

3

Neo-institutional theory asserts the importance of normative frameworks and rules in guiding, constraining, and<br />

empowering behavior. In particular, firms consist of cognitive, normative, and regulative structures and activities that<br />

bestow meaning to social behavior (Scott, 1995). Cultures, structures and routines operating at manifold levels of<br />

authority become the carriers through which institutions impact firms (Scott, 1995). Organizational practices can<br />

become, in Selznick’s words, “infused with value beyond the technical requirements at hand” (1957:17) and be adopted<br />

for the sake of legitimacy rather than improved performance (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). We contend that it is the<br />

nature of the competitive game that those who have superior performance seek stability, while the unhappy rivals seek<br />

change. As a result, Institutional processes may not produce long-term efficiency, because they end up producing rigidity<br />

and resistance to change. We argue that the theory is not clear about what it is trying to solve, since in our case the board<br />

should be preoccupied with the performance of the firm if the principle (shareholder) is to be happy.<br />

Thus, over time, organizations reflect the enduring rules institutionalized and legitimated by their social environments<br />

(DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Scott, 1995). Societal norms have been shown to influence board<br />

decisions regarding CEO selection and executive compensation (Zajac & Westphal, 1996) and how boards explain the<br />

adoption of CEO incentive plans to shareholders (Zajac & Westphal, 1995). This implies that organizations’ quest for<br />

legitimacy and the process of structuration results in the homogenization of organizations with respect to their most<br />

visible attributes (e.g., board composition , Board Effort norms, Board Breadth of perspective and Board Independence).<br />

However, this convergence of attributes may not necessarily result in efficient organizations with regard to performance<br />

since Institutional theory for example argues that board composition will be determined largely by prevailing<br />

institutionalized norms in the organizational field and society. The current environment is highly complex and therefore<br />

some researchers (e.g. Ingley & Van der Walt, 2003b) suggest that greater gender diversity on the board may be<br />

appropriate in these environments characterized by greater strategic complexity. By this, they assert, greater expertise and<br />

perspectives can be brought to bear on decision making thereby leading to higher quality decisions and ultimately, better<br />

organizational performance. The problem with institutional theory is that it ignores this issue.<br />

We note that theories of institutional isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Hawley, 1968), or the propensity of<br />

organizations in a population to resemble other organizations that operate under similar environmental conditions,<br />

suggests that boards of organizations in the same institutional set will tend to be more similar to each other than to the<br />

boards of organizations outside of their set. This means that organizations may not develop their own competitive<br />

advantage to leverage the bottom line, which sets this theory inadequate in explaining firm performance as it is not<br />

emphasizing differences in intellectual capital of such firms.<br />

Institutional theory examines the role of social pressures in shaping firm behavior (Ingram and Simons, 1995; Oliver,<br />

1997). Informal institutional pressures that correct deviant behavior arise from the behavior of industry leaders, peers,<br />

and network associates. Amid uncertainty about the ramifications of disclosing deviant behavior, the focal firm will<br />

observe how other industry members have dealt with deviance. For instance, when the focal firm sees other firms in the<br />

industry voluntarily restating earnings, it may also be compelled to do so.<br />

Interestingly, resource-based and institutional perspectives have different viewpoints to explain superior performance.<br />

Institutional perspective emphasizes homogeneity within institutions such as conforming to predominant norms,<br />

traditions, and social influence, in order to achieve superior performance (Oliver, 1997). In contrast, resource-based<br />

perspective argues that rare, specialized, and inimitable resources allow corporations to achieve superior performance<br />

under the two assumptions: resources are heterogeneously distributed across competing firms, and resources are<br />

imperfectly mobile (Barney, 1991; Oliver, 1997). We argue that the theories could be harmonized if the issue of gender<br />

diversity was incorporated in these theories.<br />

Social network theory<br />

The final theoretical perspective on board that we consider is a sociological perspective that builds upon resource<br />

dependence theory, specifically, the influence of social networks on board formation and composition. Social network<br />

theory suggests demographic similarity among board members is reflective of the organization’s emergent interorganizational<br />

network (Gulati & Gargiulo, 1999). From this perspective, board composition will reflect the social<br />

networks of the principal stakeholders (e.g., CEO, external financiers). Rather than just acknowledging the role of social<br />

networks, the theory should be all-embracing by incorporating intellectual capital which we feel is wider tem than social<br />

net works.<br />

4

Boards, for example, enable the firm to create a network without the full costs of true vertical amalgamation. Resourcepoor<br />

entrepreneurial organizations can achieve required strategic benefits by building network exchange structures with<br />

outsiders who are identified as critical resource suppliers. These relationships can stabilize the new firm in its targeted<br />

markets. It is therefore possible to attach value to these networks in the valuation of intellectual capital. While this view<br />

is consistent with the resource dependence perspective, social network theory emphasizes the importance of network<br />

formation on reputation, trust, reciprocity, and mutual interdependence (Larson, 1992). Thus, for example, our earlier<br />

discussion of resource dependence focuses on the role of the board as facilitating the acquisition of resources. In<br />

contrast, social networks theory considers the predictable paths (based on preexisting relationships) that may be used to<br />

acquire these resources.<br />

Therefore, the social network perspective is closely aligned with other theoretical perspectives. This perspective is<br />

distinct, however, in that it focuses on social networks as the primary predictor of board composition. For example,<br />

Forbes and Milliken (1999) pursued the links between group processes and diversity in the study of the literature<br />

focusing on group dynamics and their effects on board effectiveness. They highlighted such areas as board cohesiveness<br />

and effort norms (ensuring preparation, participation and analysis), cognitive conflict (leveraging differences in<br />

perspective), the presence of knowledge and skills, effects of board processes; job related diversity, other aspects of board<br />

demography (proportion of outsiders, board size, board tenure) and board dynamics across different types of boards.<br />

They concluded that board effectiveness was likely to depend heavily on social-psychological processes, particularly<br />

those pertaining to participation and interaction, the exchange of information, and critical discussion. We disagree with<br />

this perspective, however, because it does not explain the other side of the coin of how the board can help in enhancing<br />

the intellectual capital resources of the firm. This is because there is empirical evidence (Nkundabanyanga, 2006) to<br />

show that actually gender diversity on the board enhances intellectual capital performance of firms.<br />

We contend that this is harmonizable by incorporating intellectual capital as a wider set so we could develop a<br />

comprehensive framework for understanding corporate performance. Accordingly, although social networks have been<br />

posited to play an important role in the formation of boards (Birley, 1985; Khurana, 1996), we believe much greater<br />

elaboration of the impact of boards on firm’s intellectual capital is justified since Intellectual capital is generally<br />

becoming widely accepted as a major corporate strategic asset capable of generating sustainable superior firm<br />

performance (Barney, 1991).<br />

Thus, it can be considered that external governance may not be a necessary condition for controlling managers and that<br />

there should exist some other factors that augment, discipline the management, and ensure the efficient operation of the<br />

firm. Outside the standard agency paradigm, some researchers suggest that managers are controlled more or less inside<br />

the firm. Yet others believe that institutional isomorphism explains board behavior and therefore corporate performance.<br />

It is for this varying utility of agency theory, network theory, resource dependency, and institutional theory in predicting<br />

firm performance, we are proposing a comprehensive framework incorporating gender diversity, intellectual capital, and<br />

CEO celebrity.<br />

Theoretical Framework<br />

The following model describes how gender diversity on the board, intellectual capital, governance mechanisms increase<br />

corporate performance. It shows that governance mechanisms can enhance a CEO’s self-efficacy as also the performance<br />

of intellectual capital can enhance the celebrity of CEO’s. We posit that a CEO’s celebrity and his efficacy enhance his<br />

strategic choices in turn enhancing corporate performance. It predicts that a manager’s strategic choices can lead to both<br />

startling performance and spectacular failures of firms because of his celebrity and self-efficacy. Board diversity,<br />

intellectual capital and governance mechanisms shape a firm’s culture and voluntary disclosure proclivity of firms and<br />

this in turn affects corporate performance. The framework shows some demographic factors as being control variables.<br />

Figure 1: Proposed theoretical model<br />

5

Gender diversity<br />

on Board<br />

-Board Composition<br />

-Board Effort norms<br />

-Board Breadth of perspective<br />

-Board Independence<br />

Intellectual capital<br />

-Human capital<br />

-Structural capital<br />

-Relationship capital<br />

Governance<br />

Mechanisms<br />

-External governance mechanisms<br />

-Internal governance mechanisms<br />

-pre-nomination discussions<br />

-post-nomination evaluations<br />

The above theoretical model together with our arguments earlier guides us in posing the following hypotheses:<br />

Hypotheses<br />

Organizational<br />

culture<br />

Corporate<br />

voluntary<br />

disclosure<br />

CEO Celebrity<br />

Self-efficacy<br />

H1: Firms with effective internal governance mechanisms will result in higher corporate performance proxied by future<br />

viability, financial performance, shareholder value, market performance and sales performance.<br />

H2: Firms with effective internal governance mechanisms attract and leverage greater intellectual capital<br />

H3: Firms that are leveraging the intellectual capital have higher chances of attracting celebrity CEOs which in turn<br />

enhances corporate performance.<br />

H4: The greater the availability of information about a CEO’s idiosyncratic personal behaviors the greater the likelihood<br />

that a CEO will perceive control over the present and future actions and performance of the firm.<br />

H5: CEO Celebrity has a positive relationship with firm’s market value because of the stakeholders’ infatuation with<br />

celebrities.<br />

H6: Firms in constant search of intellectual capital to harness current market environment have better corporate<br />

performance premised on future viability, financial performance, shareholder value, market performance and sales<br />

performance than those that are not.<br />

6<br />

Manager’s<br />

strategic<br />

choices<br />

-Resource identification<br />

-Resource<br />

development/protection<br />

-Resource deployment<br />

Firm size, industry,<br />

firm age, etc<br />

Corporate<br />

performance<br />

-Future viability<br />

-Shareholder value<br />

-Market performance<br />

-Sales performance<br />

-Financial<br />

performance

H7: Firms with diverse boards are in a better position to leverage intellectual capital<br />

H8: A board of Directors that is not determined largely by prevailing institutionalized norms will have a positive effect<br />

on corporate performance based on future viability, financial performance, shareholder value, market performance and<br />

sales performance<br />

H9: A diverse board of directors affects the culture of the organization in question and consequently corporate voluntary<br />

disclosure proclivity.<br />

H10: The amount of Voluntary corporate disclosure depends on intellectual available in the focal firm and hence<br />

affecting firm performance.<br />

Theoretical and methodological implications<br />

Previous research have concentrated on the use of financial accounting measures of corporate performance and the use of<br />

accounting data obtained from only listed firms. Hence, they have almost all invariably employed quantitative research.<br />

Our research will be a blend of quantitative and qualitative study (methological triangulation). In addition, a major<br />

criticism of extant board research is that it focuses almost exclusively on large, mature organisations (Daily & Dalton,<br />

1993; Dalton & Kesner, 1983) as compared with smaller and newer firms. We will control for such factors like age of<br />

the firm, industry, size and other demographic factors aware that Individual company differences in demographic factors<br />

can have an impact on the relationships between variables (Marco, Mirjam and Cools, 2003). Given the fact that most<br />

Ugandan firms are not listed, we will include non-listed firms in addition to a census of all listed firms in Uganda on the<br />

Uganda Securities Exchange. We will use non-probabilistic sampling (in particular snowballing) with the aim of getting<br />

pure play comparison companies. Our research frame will require that the amount (importance) of intellectual capital be<br />

measured within the firms. A survey will be conducted to fulfill this need.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Researchers studying corporate boards have employed a wide set of theoretical perspectives to understand the<br />

characteristics, behavior, and effects of executives (Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1996). Agency theory (Jensen and Meckling,<br />

1976) is among the most recognised in research on the contribution of boards (Zahra and Pearce, 1989) as is the use of<br />

the board as a mechanism for managing resource dependencies (Johnson, et al., 1996; Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). It is<br />

common for researchers also to invoke institutional theory (DiMagio and Powell, 1983; Meyer and Rowan, 1977) and<br />

have examined the role of social networks (Granovetter, 1985) in boards (Birley, 1985; Gulati & Gargiulo, 1999;<br />

Larson, 1992; Westphal, 1999). Our theoretical review has produced a theoretical concern brought about by the gaps in<br />

the knowledge we have identified and we feel that filling these gaps will result in advancement of knowledge in the area<br />

of corporate performance. We have argued that these (see the review) theories’ corporate performance predictive validity<br />

is contingent upon the existence of appropriate intellectual capital and gender diversity on the board. These together<br />

with governance mechanisms, have been employed as predictor variables of corporate performance.<br />

7

References<br />

1. Baysinger, B. D and Bulter, H. N (1985); Corporate Governance and the Board of Directors: Performance effects of<br />

changes in board composition; Journal of Law, Economics and Organizations, (1), pp. 101-124<br />

2. Benston G.J.(1982b), An analysis of the role of accounting standards for enhancing corporate governance and social<br />

responsibility, Journal of accounting and public policy, Vol. 1<br />

3. Benston, G.J. (1982a), Accounting and Corporate Accountability, Accounting, Organization and Society, Vol. 7<br />

No. 2<br />

4. Berle Jr, Adolf A. and Means C. Gardiner)1932). The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York, NY:<br />

The Macmillan Company<br />

5. Birley, S. (1985); The role of networks in entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 1<br />

6. Birley, S. (1985); The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of business Venturing, Vol.1: 107-<br />

118<br />

7. Brunsson, N. and J.P. Olsen (1993); The reforming organization (London: Routledge).<br />

8. Carpenter, M.A. and Westphal, J.D. (2001), The strategic context of external network ties: Examining the impact<br />

of director appointments on board involvement in strategic decision making; Academy of management Journal Vol.<br />

28, pp.548-73<br />

9. Corley T.A.B (1990), Emergence of the theory of industrial organization, 1890-1990; Business and Economic<br />

History, Vol 19. No 2<br />

10. Daily, C. & Dalton, D. (1993), Board of Directors leadership and structure: Control and performance implications.<br />

Entrepreneurship theory and practice. Vol. 17<br />

11. Daily, C. and Dalton, D. (1994b). Corporate governance and the bankrupt firm: An empirical assessment. Strategic<br />

<strong>Management</strong> Journal, Vol.15: 643-654.<br />

12. Daily, C. and Dalton, D. 1(994a). Bankruptcy and corporate governance: The impact of board composition and<br />

structure. Academy of <strong>Management</strong> Journal, 37: 1603- 1617.<br />

13. Dalton, D. & Kesner, I. (1983); Inside/outside succession and organizational size: The pragmatics of executive<br />

management, Academy of management Journal, Vol. 26<br />

14. DiMaggio, P. & Powell, W. (1983) The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in<br />

organizational fields, American Sociological Review Vol 48 No.2.<br />

15. Donaldson, G., Lorsch, J., (1983). Decision Making at the Top. Basic Books, New York.<br />

16. Drejer, A (200); Organizational learning and competence development; the learning organization Vol. 7 No. 4<br />

17. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review. Academy of <strong>Management</strong> Review, Vol. 14,<br />

pp. 57-74.<br />

18. Fama, E. & Jensen, M. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 26: 301-<br />

325.<br />

19. Fama, E. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, Vol.88: 288-307.<br />

20. Finkelstein, S. and Hambrick, D.C. (1996); Strategic Leadership: Top executives and their effects on Organisation.<br />

New York; West Publishing Company<br />

21. Forbes, D. and Milliken, F. (1999); Cognition and corporate governance: Understanding boards of directors as<br />

strategic decision making groups. Academy of management Review, Vol.24: 489-505<br />

22. Granovetter, M. (1985); Economic action and social structure: A theory of embeddedness. American Journal of<br />

sociology, Vol. 91.<br />

23. Gulati, R. and Gargiulo, M. (1999); Where do interorganizational networks come from? American Journal of<br />

Sociology Vol. 104<br />

24. Gulati, R., and Gargiulo, M. (1999); Where do interorganizational networks come from? American Journal of<br />

sociology, Vol.104: 1439-1493<br />

25. Guy B. Peters (2000); Institutional Theory: Problems and Prospects. Political Science Series. Institute for Advanced<br />

Studies, Vienna<br />

26. Hawley, A. (1968). Human ecology, in D. L. Sills (Ed.) <strong>International</strong> Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 328-<br />

337, New York: MacMillan.<br />

27. Hitt, M., Ireland, R. and Hoskisson, R. (2001); Strategic management: Competitiveness and Globalization, Southwestern,<br />

Cincinnati, OH<br />

28. Ingley, C.B. and Van der Walt, N.T. (2003b), Board configuration: Building better boards, Corporate governance:<br />

The international Journal of Business in society, Vol. 3 No.4<br />

8

29. Johnson, J., Daily, C., and Ellstrand, A. (1996); Boards of directors: A review and research agenda. Journal of<br />

<strong>Management</strong> Vol. 22<br />

30. Khurana, R. (1996); Finding the right CEO: Why boards often make poor choices. MIT Sloan <strong>Management</strong><br />

Review, Cambridge, MA: 91-95<br />

31. Kunz, A.H., and Pfaff, D (2002); Agency theory, performance evaluation and the hypothetical construct of intrinsic<br />

motivation. Accounting, organizations and society Vol.27<br />

32. Larson, A. (1992); Network dynads in entrepreneurial settings: A study of the governance of exchange<br />

relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly Vol.37: 76-104<br />

33. March J.G. and J.P. Olsen (1989); Rediscovering Institutions (New York Press)<br />

34. March, J. G, and J. P. Olsen (1984), The New Institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life, American<br />

Political science Review, Vol.78, 738-49<br />

35. March, J. G, and J. P. Olsen (1989); Rediscovering institutions (New York: Free Press).<br />

36. March, J.G. and J.P. Olsen (1984); The New Institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life, American<br />

Political Science review Vol. 78, 738-49 York: Macmillan.<br />

37. Marco Van Herpen, Mirjam Van Praag and Kees Cools (2003), The effects of performance measurement and<br />

compensation on motivation. An empirical study<br />

38. Mathew L. A. Hayward, Violina P. Rindova and Timothy G. Pollock (2004); Believing one’s own press: The<br />

causes and Consequences of CEO Celebrity. Published online in Wiley InterScience<br />

(www.interscience.wiley.com).DOI:10.1002/smj.405<br />

39. MeyerJ, Rowan B. (1977); Institutional Organisations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal<br />

Sociology Vol.83: 340-363<br />

40. Nkundabanyanga K.S (2006), Gender diversity on the board of directors, intellectual, and firm performance,<br />

Masters Dissertation; Makerere University<br />

41. Olsen J. P and B.G Peters (1996); Introduction: Learning from experience? In Olsen and Peters, eds., Lessons from<br />

Experience: Experimental Learning from Administrative Reform in Eight Democracies (Oslo: Scandinavian<br />

University Press).<br />

42. Penrose E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. New York, NY: John Wiley.<br />

43. Pfeffer J. (1972); Size and composition of corporate boards of director: the organization and its environment.<br />

Administrative Science Quarterly Vol.17: 218-229<br />

44. Pfeffer, J. and Salancik, G. (1978); The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. New<br />

York: Harper Review<br />

45. Scott, W.R. (1995); Institutions and organizations (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage)<br />

46. Selznick, P. (1949); TVA and the Grass Roots: A Study of the Sociology of Formal Organizations. New York:<br />

Harper & Row.<br />

47. Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in Administration. New York: Harper and Row.<br />

48. Stigler, G.J. (1964a), Public regulation of the securities markets. The Journal of Business, April pp.112-33<br />

49. Stigler, G.J. (1964b), Comment. The Journal of Business, October, pp. 414-22<br />

50. Sunder, S. (1997). Theory of Accounting and Control. Cincinnati, OH: Southwestern Publishing.<br />

51. Wade M. and Hulland J. (2004); The Resource-based View of information system research: Review, extension and<br />

suggestion, MIS Quarterly review, Vol. 28 No. 1<br />

52. Weisbach, M. (1988). Outside directors and CEO turnover. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol.20: 431-460.<br />

53. Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic <strong>Management</strong> Journal, 5: 171-180.<br />

54. Westaphal, J.D and Milton, L.P (2000); How experience and Networks ties affect the influence of demographic<br />

minorities on corporate boards; Administrative Science Quarterly, 45 (1), pp. 366-398<br />

55. Westphal, J.D. (1999); Collaboration in the board room: Behavioral and performance consequences of CEO-board<br />

ties. Academy of <strong>Management</strong> Journal Vol. 42<br />

56. Zahra, S.A and Pearce, J.A. (1989); Boards of Directors and Corporate financial performance: A review and<br />

integrative model. Journal of management, Vol.15<br />

57. Zajac E.J. and Wstphal J.D. (1995); Who shall govern? CEO/board power, demographic similarity, and new<br />

director selection. Administrative science quarterly Vol. 41 60-83<br />

58. Zajac E.J. and Wstphal J.D. (1996); Director reputation, CEO-board power, and the dynamics of board interlocks.<br />

Administrative science quarterly Vol. 41 507-529<br />

59. Zucker.L. (1987) Institutional Theories of Organizations, <strong>Annual</strong> Review of Sociology Vol.13, 443-64<br />

9

LEADERSHIP AND CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES FOR SMALL AND MEDIUM<br />

ENTERPRISES IN KENYA: A REVIEW OF LITERATURE WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO THE<br />

MOBILE TELEPHONE VENDING.<br />

By<br />

Robert Kuloba<br />

Kenya Institute of Administration (KIA)<br />

P.O. Box 23030-00604<br />

Lower Kabete, Nairobi<br />

Email: rkuloba@kia.ac.ke<br />

Abstract<br />

The Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation (ERS) 2003 – 2007 subsumes a very pertinent<br />

role for the small and medium enterprises (SME) in Kenya. The latest review of the ERS for the year 2005 estimates<br />

that total employment both in the modern and informal sector, increased by 6.5 % in the year 2004 to stand at 7.8<br />

million with the informal sector generating 437,900 more jobs against the formal sectors 36,400. Growth was noted<br />

more in manufacturing and mobile telephone service providers where new mobile phone connections increased by 42.0%<br />

from 1,097 thousand in 2003 to 1,558 thousand in 2004. As a consequence, there were a significant number of new<br />

entrants into this sector. Although there are no entry and exit statistics for these new entrants, their operations are often<br />

perceived as hinged on figuratively putting out fires on a daily basis in a bid to gain both inter and entrepreneurial<br />

capacity. With this in mind, this paper attempts to review the varied management and leadership challenges that this<br />

growth portends as mobile telephone service venders concentrically move from leading oneself to leading a team or an<br />

organization. This review is considered significant since the government is increasingly giving more emphasis on work<br />

based solutions to enhancing performance i.e. moving away from theory to evidence based practice and which have<br />

significant policy implication for KIA in terms of developing training programs that specifically address this sector. The<br />

paper also identifies the elements of successful leadership development, and assesses the skills or competencies that need<br />

to be developed if SME’s have to continue being the engine of growth for wealth and employment creation.<br />

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND<br />

The complexity of the constantly changing environment in which small and medium enterprises (SME’s) operate has<br />

significant implications for their effectiveness. Internal and external pressures continuously challenge their identity and<br />

ability to achieve their mission. This can be particularly significant where rapid change processes are triggered by<br />

contextual influences, whether negative (phobia for non white collar jobs), or positive (consumer habits) as has been the<br />

case in the rapidly growing mobile telephony sector in Kenya.<br />

Until recently, there had been general resistance among educated people to venture into informal sector as a key source<br />

of employment. But with the introduction of the cellular mobile service in Kenya in 1993, coupled with phenomenal<br />

growth in the number of subscribers particularly in the last six years, the number of venders/dealers in this seemingly<br />

elitist business venture has been growing due to limited entry and exit barriers. This introduces an interesting dimension<br />

in addressing the un employment challenges facing Kenya i.e. why such unprecedented growth trajectory. Understanding<br />

the ingredients of what makes economies grow remains one of the most vexing questions facing policymakers and<br />

economists i.e. why are some sectors fated to race ahead (high entry traffic for small businesses) while others lag behind?<br />

The exponential growth in this sector is attributable to the enactment of the Kenya Communications Act 1998 that saw<br />

both Safaricom and Celtel Kenya realize tremendous growth in subscriber rollout with a combined subscriber base of<br />

about 4,611,970 as at June 2005 1 . Consequently, the sector has served as a major fall back position for the un employed<br />

1 Mobile phones are changing the way that many people live and work. They make business easier and more<br />

efficient. They help families and communities to stay in touch, and individuals to feel connected. There is an<br />

exciting mix of social and economic groups of customers across the social spectrum - from civil servants,<br />

business executives and artisans to housewives and students<br />

10

population in Kenya especially in areas of dealerships 2 simu ya jamii (community phones) and what is commonly called<br />

ongea 24/7 dealers (pre paid electronic airtime vending system using mobile handsets). The majority of those venturing<br />

into these businesses though educated do not have the necessary management and leadership skills (NESC, 2006). And<br />

emerging problems of disguised unemployment especially in the public sector, it is argued that any solution to the<br />

current problem of high unemployment must therefore address this sector and the challenges arising there from.<br />

The capacity of SME’s to analyze and understand their internal and external environment and adopt their strategies with<br />

new conditions can help them to respond appropriately to these challenges. However, some do this more consciously and<br />

successfully than others. This paper’s premise is that by facilitating an understanding of management and leadership<br />

capacities, and how they can be strengthened, this may help SMEs increase their effectiveness. It reviews current<br />

thinking, drawing on literature from fields such as organizational learning and change, strategic management, systems<br />

thinking and complexity theory. It then proposes a number of considerations that may guide efforts to develop<br />

management and leadership competencies particularly of emerging or entry level businesses with specific reference to<br />

mobile telephone service vendors.<br />

PURPOSE OF THE REVIEW<br />

The management of small and medium enterprises considering that there are no entry and exit barriers is inundated by<br />

multiple and diverse problems. The recently launched Vision 2030 for Kenya identifies a number these challenges to<br />

accelerated economic growth as unemployment (especially among the youth as most jobs can be found in the informal<br />

sector), rising disparities in income (hence the need for income redistribution), rapid urbanization (at a rate of 6% per<br />

annum) and low savings ratio (16%) compared to the need. Given that urban areas will hold 60% of Kenya’s population<br />

by the year 2030, then it is imperative that the economy must grow as projected at a rate of 10% and in the identified<br />

growth areas. A critical challenge to unlocking the potential to this growth is the consolidation of the gains already<br />

witnessed in the growth of the mobile telephony service sector that holds the key to economic growth through<br />

generation of employment opportunities to absorb the large army of unemployed and particularly the youth. Studies<br />

show that there is a high correlation between high mobile subscriptions or penetration and GDP growth not only in<br />

Africa but in the developed works as well. In Kenya, the government has also recognized the vital role that this sector<br />

plays in development and GDP growth as evidenced in the latest review of progress made towards implementation of the<br />

economic recovery strategy for wealth and employment creation.<br />

With an exponential growth 3 in the mobile telephony sector and the many entrants (no literature on entry and exit) in<br />

the form of dealerships, simu ya jamii as well as ongea 24/7 dealers, this has tended to accelerate business dynamics that<br />

has boosted the growth in subscriber base. The entrants to this sector in the three forms identified above do face a range<br />

of challenges that forms the thesis of this paper. As new entrants and although well educated, they often lack skills in<br />

management and leadership which leaves them figuratively putting out fires on a daily basis in a bid to gain both intra<br />

and entrepreneurial capacity at a personal as well as organizational levels. Although there is consensus that small and<br />

medium sized enterprises will fuel job creation, one pertinent question remains, how many of the people going into such<br />

businesses as witnessed in the phenomenal growth of the mobile telephony sector have experience and knowledge of how<br />

to use analytical and adaptive capacities to cope with the challenges of this new and rapidly changing technology based<br />

business ventures.<br />

METHODOLOGY<br />

By and large, this was a desk study that focused primarily on reviewing literature on leadership and how this can be<br />

configured to the unique needs of mobile phone vendors. However, as great limitation to the review was that the<br />

reviewer is not a leadership theorist. The analysis of information reviewed and presented should therefore be viewed in<br />

the context of the reviewer’s institutional affiliation which has a focus on capacity building i.e. arising from the review,<br />

one question that the reviewer kept asking himself was what kind of training programs can be developed to target this<br />

market niche?<br />

2 Dealerships are well established businesses (at the apex of the entrepreneurship funnel) whereas simu ya<br />

jamii and 24/7 as well as other community phone services are still at the entry level and characterized by a<br />

number of vexing problems<br />

3 The number of mobile phone connections were at par with fixed land line connections at approximately<br />

300,000 in the year 2001, compared to 4.6million and less that 0.3 million respectively in 2005 (fixed line<br />

teledensity dropped)<br />

11

Limitations<br />

Nonetheless, the review does recognize that lack of or less data and information from which to draw firm conclusions<br />

about the impact of mobile service vendors, about efficiency and effectiveness in their operations, about sustainability<br />

(their ‘mortality’) and the gender balance remains a major challenge to evidence based decision making.<br />

MANAGEMENT AND LEADERSHIP FOR SMALL BUSINESSES<br />

Introduction<br />

“Who doesn’t want to live more whole heartedly? Who would deny deeper experience of being alive and<br />

connecting more powerfully with those activities or ventures that they hold so dearly? Who says no to a deeper<br />

experience of joy, a chance to contribute to success and well being of others? Unless one is seriously deranged,<br />

these choices can be provided one has the courage and know-how (self fulfilling prophecy)”. (Wabala, 2006)<br />

With high entry level in small businesses as evidenced in the phenomenal growth in the mobile telephony sector, it takes<br />

total commitment to improve performance, create greater happiness and to escape emotional suffering especially if the<br />

business is on a down turn. This retinue of challenges calls for a critical review of the operations of mobile telephone<br />

venders who more often than not are expected to portray business acumen as well as acting as agents or ‘technical<br />

advisers’ of their respective customers irrespective of service providers.<br />

Theoretical Foundations<br />

While the terms ‘leadership’ and ‘management’ are commonly used interchangeably, many theorists distinguish between<br />

them. ‘Leaders’ are expected to provide strategic direction and inspiration, initiate change, encourage new learning, and<br />

develop a distinct organizational culture, while ‘managers’ are seen to plan, implement and monitor on a more<br />

operational and administrative level (Dwyer, 2006). As a consequence there is a perception that management is<br />

concerned with resolving specific issues and day-today challenges, while leadership is about the bigger picture and<br />

promoting change (Keller, 2006). The reality is that those people with responsibility to ensure that plans are<br />

implemented, systems are effective, and staff motivated are both leaders and managers. This overlap of roles is<br />

particularly apparent in smaller organizations similar to the focus of this review where one person often has to play both<br />

roles simultaneously (White, 2005).<br />

However, in practice leadership 4 and management are integral parts of the same job both of which need to be balanced<br />

and matched to the demands of the situation. Hence any analysis that makes a clear distinction between managers and<br />

leaders can at best be misleading (White 2006). Effective leaders have to demonstrate some managerial skills on one<br />

hand while good managers should display leadership qualities on the other making the relationship between the two<br />

symbiotic. There is therefore no water tight formula on the extent or synergy for which these skills or attributes can be<br />

used or displayed within an organization or business entity. In practice it depends on the judgment of the individual<br />

involved and the context in which they find themselves (Bolden 2004).<br />

Nonetheless, leadership remains a grey area that is much contested given the plethora of different theories that attempt<br />

to mystify the two concepts. For instance, it suffices in literature that some of the early leadership theorists tended to<br />

focus on identifying and isolating a finite number of ‘traits’ that were exhibited by ‘great men’ based on psycho-dynamic<br />

perspectives. Some of the limitations of trait theories prompted others like McGregor (1960) and Blake and Mouton<br />

(1964) to highlight the importance of what leaders actually do, rather than their personal characteristics. They focused<br />

on leadership<br />

behavior and styles, often advocating for a ‘team management’ approach. The next wave of theorists (such as Fielder<br />

1967 and Hersey and Blanchard 1977) emphasized the ‘situational’ aspect of leadership – in other words they believed<br />

that the effectiveness of different leadership styles depended largely on the particular situation. Within this framework<br />

4 In the last 25 years, leadership has become one of the most talked about elements of organizations. As an<br />

illustration of this, today there are more than 16,000 publications referenced to leadership on the<br />

Amazon.com web-site, up by almost 50% in the last two years alone. Yet amidst this accelerating activity,<br />

there is still no widely accepted definition of leadership and no common consensus on how best to develop<br />

leaders.<br />

12

John Adair highlighted the importance of a leader being able to balance the needs of the task, the team and the<br />

individual (1973).<br />

From the late 1970s onwards the concept of ‘transformational leadership’ gained currency with writers like Burns<br />

(1978) and later Covey (1992) advocating that leadership should be about transforming people and organizations by<br />

engaging their hearts and minds or what Eric Garner calls the Pygmalion effect (treat a man as he is and he will remain as<br />

he is and treat a man as he can or should be and he will become as he can or should be).<br />

Other leadership theories have emphasized the importance of the ‘charismatic leader’ or the ‘servant leader’ particularly<br />

in the last 20 years (Greenleaf 1998). Others have highlighted the spiritual dimension of leadership (Owen 1999;<br />

Kakabadse and Kakabadse 1999) or what Wabala calls the heart of a servant leader 5 . These ideas have been<br />

complemented by recent work on ‘distributed leadership’, based on the notion of leadership being first and foremost a<br />

relationship of mutual influence between leaders and followers. The ‘followership’ of an organization or business entity,<br />

and how freely they attribute leadership authority, is also increasingly recognized as having an important role to play in<br />

the behavior and success of a leader (Howell and Shamir 2005).<br />

Good as this review may be, it suffices that almost all this leadership theory is based on a very specific context – Western<br />

management of private sector companies. As a result much of the current leadership research is not relevant to the<br />

different contexts in which small businesses operate or work given the great dynamism (Smillie and Hailey 2001;<br />

Fowler, Ng’ethe and Owiti 2002; Hailey and James 2004). While these studies have increased our understanding of the<br />

static characteristics of effective leadership within small organizational settings, few have tried to explore the dynamics of<br />

how leaders change and develop within small enterprises that might have either just one or two people. Yet as social<br />

identity theory suggests, for leadership development approaches to be effective, they must be designed with an<br />

understanding of the historical social forces, pressures and realities affecting small and medium enterprises in local<br />

contexts and which influences them to change behavior.<br />

POLICY FOCUS FOR GROWTH OF SMALL BUSINESSES<br />

The Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation 2003 – 2007 underscores the major challenges<br />

facing Kenya as being restoration of economic growth, generation of employment opportunities to absorb the youth<br />

(they comprise 75% of the national population) and reduction of poverty levels. It may be important to recognize here<br />

that the paper was developed against a backdrop of rising poverty levels in the country from 48% in 1990 to 56% in<br />

2001 However; it does identify the small and micro enterprises sector 6 (SME’s) as an integral part of employment<br />

creation over the four year period. The sector currently employs over 6 million (78% of the national labour force)<br />

mainly young people compared to 1.8 million, in the formal sector. In 2005 alone, the sector provided employment for<br />

over 474,000 workers against 437,000 created in 2004. This employment figures are benchmarked on the 1998/1999<br />

labour force survey, the 1999 population and housing census projections and the <strong>Annual</strong> labour enumeration survey of<br />

the central bureau of statistics (CBS, 2003).<br />

The key sub sectors that registered increased growth included manufacturing and mobile telephone services providers.<br />

MOBILE TELEPHONY SERVICES PROVISION<br />

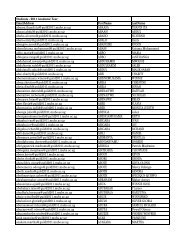

The growth in the mobile telephone services in Kenya has been exponential. With about 15,000 subscribers in 1998 to<br />

over 4.5 million in 2005, the mobile telephone sector remains one of the fastest growing sectors in Kenya with great<br />

potential for employment creation (see chart 1) below. Given that there are no entry and exit statistics, there is a flurry of<br />

activity particularly as regards vending business from established dealerships, simu ya jamii, pre paid electronic airtime<br />

vendors using mobile handsets to retailers operating roadside kiosks.<br />

5<br />

The Bible exhorts us to gird our hearts with all diligence for it is out of it that the issues of life flow Prov.<br />

4:23<br />

6<br />

A comprehensive policy paper on development of micro and small enterprises is being developed. The<br />

paper outlines the way forward as regards creation of an enabling legal and regulatory framework, funding<br />

and skills development strategies, research and development and an effective policy co-ordination<br />

mechanism.<br />

13

Subscription<br />

5,000,000<br />

4,500,000<br />

4,000,000<br />

3,500,000<br />

3,000,000<br />

2,500,000<br />

2,000,000<br />

1,500,000<br />

1,000,000<br />

500,000<br />

Source: www.cck.go.ke<br />

0<br />

Chart 1: Growth in mobile telephone services<br />

1998/1999 1999/2000 2000/2001 2001/2002 2002/2003 2003/2004 2004/2005<br />

Year<br />

14<br />

Mobile Subscribers<br />

Fixed Line Subscriber Connections<br />

<strong>Management</strong> of these business enterprises from sole proprietorships to established dealers entail a range of dynamic<br />

process which requires constant vigilance. Integral to their success is the leadership model commonly referred to as<br />

P.O.L.I.C.E. and which is grounded on a foundation of accountability and self regulation emerging and established<br />

businesses must embrace:<br />

P. - Planning<br />

O. - Organizing<br />

L. - Liability/accountability<br />

I. - Information/communication<br />

C. - Control/accountability<br />

E. - Ethics/integrity<br />

This requires an introspective assessment of oneself or more precisely making that assessment using three key<br />

requirements;<br />

i. A definite purpose in mind<br />

ii. Understanding of the environment in which you are operating in and particularly the forces that affect or<br />

impede fulfillment of that purpose<br />

iii. Creativity in developing responses to those forces<br />

Given a near fanatical and steady demand (speculative) and growth of mobile phone services which is over ten times the<br />

size of fixed network subscribers, traffic in terms of entry into mobile phone vending business is expected to continue<br />

growing. This is evidenced by and large by the fact that there are now over 5000 community payphones 7 alone in the<br />

country. They have become apparently easy to rollout and manage while ensuring wide availability of the same at<br />

convenient and strategic points for the public by offering ready accessibility to telephone services. Other than the pay<br />

phones, other emerging services arising from the growth of the mobile telephone sector are after sales service of handsets<br />

as well as charging services (both where there is mains electricity and where there is none). Interpretation of this growth<br />

and what it portends for the small business in terms of management and leadership has to be inferred within the<br />

framework of the entrepreneurial 8 funnel (from pre entrepreneurs to maturing entrepreneurs).<br />

7 The two mobile service operators had obligations in their licenses to provide payphones services and have<br />

facilitated the availability of this service through community payphones run by individuals.<br />

8 From the time an individual starts thinking of getting into business to the time they are established<br />

entrepreneurs running established businesses

PRACTICAL ANALYSIS TO RESOLVING KEY OBSTACLES<br />

A quick transect walk across the city of Nairobi as well as other peri urban centres reveals a mushrooming of vendors.<br />

And given the governments recognition of the vital role of the mobile telephone service providers in employment<br />

creation, there is need for targeted measures to address the challenges that such emerging business persons are facing in<br />

terms of management and leadership skills. For instance, pertinent question would be, how many of these business<br />

enterprises have a vision or a mission or which businesses have registered remarkable success in their operations to act as<br />

case studies? Considering that the service offered is technology based and most customers find these outlets the first<br />

point of contact, this demands that they must ideally operate on the basis of the P.O.L.I.C.E. model.<br />

As earlier noted, without evidence based factual information on entry and exit traffic and the reasons for or against,<br />

success stories that can be used for mentoring may not be easily identified unlike in the agricultural sector where success<br />

models are well documented. This may also make it quite tricky in terms of providing tools for guidance to successfully<br />

plan and manage such businesses within the framework of entrepreneurial funnel as modified by Techno serve. Within<br />

the mobile telephone services provision, most of the businesses according the funnel framework are at their infancy<br />

stages or what is called start up stage as emerging entrepreneurs. However at the narrowest point of the funnel is what is<br />

called established entrepreneurs and these are normally dealers sub contracted by mobile phone providers. They are also<br />

fully registered with well established business premises and can only be found in major towns and cities in Kenya. To<br />

incrementally grow in portfolio, they need in depth industry wide and value chain based technical assistance as well as up<br />

scaling services and access to seed money. For the established businesses, there may be need for benchmarking outside the<br />

local market niche<br />

CONCLUSIONS<br />

The paper has explored the realities of change as occasioned by the introduction of the mobile telephony services in<br />

Kenya. The potency of many businesses to keep abreast with this fast and technology based market niche can at best be<br />

described as ingenious going by the number of business installations that can be seen in many urban centers. The<br />

confidence exhibited by consumers through their unique consumption habits that border on impulse buying portend a<br />

number of leadership and management challenges to this first growing business. The paper shows that the efficiency of<br />

these enterprises will first and foremost be enhanced through collection of analysis of evidenced based data and<br />

information on trends and emerging challenges. The paper has brought out the issue of capacity as an important<br />

constraint that can be address by either building their own capacity or having targeted measures aimed at deepening the<br />

concept of mentoring particularly at entry level. This is because the challenges they are facing diverse and technology<br />

laden particularly as regards the kind of services requested by clients. Another option could be use of volunteer<br />

internships.<br />

15

References<br />

1. Bolden, R. and Gosling, J. (2006) ‘Leadership competencies, time to change the tune’, Leadership, 2(2): 147–63.<br />

2. Erick Garner, 2005: The Pygmalion Effect www.managetrainlearn.com<br />

3. Fowler, A., Ng’ethe, N. and Owiti, J. (2002) ‘Determinants of Civic Leadership in Kenya’, IDS Working Paper,<br />

University of Nairobi.<br />

4. Government of Kenya, 2003: The Economic Recovery Strategy Paper for Wealth and Employment Creation 2003<br />

– 2007, Government Printer.<br />

5. Government of Kenya, 2005: ERS review reports. www.cbs.go.ke<br />

6. Kaplan, A. (2002) Development Practitioners and Social Process: Artists of the Invisible, London: Pluto Press.<br />

7. Keller, Micheal 2006: Strategic leadership www.ezinearticles.com<br />

8. Smillie, I. and Hailey, J. (2001) Managing for Change: Leadership, Strategy and <strong>Management</strong> in Asian NGOs,<br />

London: Earthscan.<br />

9. White, Barbara 2005: Seven personal characteristics of a good leader www.ezinearticles.com<br />

10. Wabala, Daniel 2006: The heart of servant leader www.ezinearticles.com<br />

11. Safaricom; www.safaricom.co.ke<br />

12. Communications Commission of Kenya <strong>Annual</strong> Report, 2005: www.cck.co.ke<br />

13. Government of Kenya, 2006: Making of ……Kenya Vision 2030, Transforming National development:<br />

www.nesc.go.ke<br />

14. Government of Kenya, 2006: Making of …….Kenya Vision 2030, A historical perspective and background brief<br />

of Kenya’s Economy and the issues leading to the formation of the National Economic and Social Council<br />

(NESC).<br />

15. CEML Framework of <strong>Management</strong> and Leadership Abilities www.managementandleadershipcouncil.org<br />

16. Investors in People Leadership and <strong>Management</strong> Model www.investorsinpeople.co.uk<br />

16

SUB-THEME : SOCIO-CULTURAL ISSUES AND DEVELOPMENT<br />

TOPIC : THE DREAM OF ENTERPRISE CULTURE DEVELOPMENT IN KENYA:<br />

THE STRATEGIC ROLE OF THE KENYA INSTITUTE OF<br />

ADMINISTRATION (KIA) TOWARDS THIS END<br />

AUTHOR : MWANGI, Jane W J<br />

DESIGNATION: Senior Principal Lecturer, KIA and Doctoral Student in Entrepreneurship, Kenyatta<br />

University, Nairobi, Kenya<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

High entrepreneurial activity ensures employment generation, poverty reduction and sustainable development. The challenge of exploiting<br />

entrepreneurial talents to foster such development occupies all countries, which regard abundant entrepreneurs an essential resource in<br />

enterprise culture development.<br />

Many researches reveal that culture and entrepreneurial propensity works in tandem in developing entrepreneurial talent. Some scholars<br />

contend that consistently fostering culture supports entrepreneurial behaviour. Others support the development of enterprise culture through<br />

abundant positive role images of successful entrepreneurs, small business familiarization during youth, network development, formal and<br />

informal learning unfortunately enterprise culture is under-developed in Kenya. This paper highlights the growing need to investigate ways of<br />

promoting enterprise culture in Kenya, a country faced with high unemployment level and little business tradition.<br />

The problem of investigation was that a weak enterprise culture exists in Kenya in spite of the many players and efforts of the enterprise<br />

support system of which the Kenya Institute of Administration (KIA) is part. Enterprise culture development requires such a system. A big<br />

gap exists because reportedly the system offers entrepreneurship training, research and consultancy support necessary in enterprise culture<br />

development. Yet, enterprise support system has been in place and in particular, KIA has continued offering training, research and<br />

consultancy as its core business areas. Hence enterprise dream in Kenya in not realized.<br />

The purpose of this paper therefore, is to establish the challenges of entrepreneurship examine the strategic and facilitative role that the<br />

Institute plays in enterprise culture development. This paper has used desk research to align existing literature with underlying principles of<br />

enterprise culture. It is based on Gibb’s (1988) theoretical framework, which leverages enterprise culture components. The role of these<br />

components in entrepreneurial culture development is under-searched in Kenya. Data was analyzed using manually and presented mainly<br />

using textual form.<br />

The key finding in this study is that many entrepreneurs require entrepreneurial training, research and consultancy support. The Institute<br />

“lives entrepreneurship” and has generally continued providing entrepreneurial support, but little of its input is purely geared towards<br />

entrepreneurship<br />

The paper concludes that KIA provides more entrepreneurial support. The paper has recommended that the Institute should continuously use<br />

highly facilitative approaches and proactively up date itself on specific entrepreneurship areas relevant to its clientele. Evidence is provided that<br />

KIA can do more towards this end by re-engineering its training, research and consultancy initiatives in collaboration with other players in the<br />

support system. This will help in the realization of the enterprise culture dream.<br />

ABBREVIATIONS<br />

BDS - Business Development Services<br />

CBS - Central Bureau of Statistics<br />

EDP - Enterprise Development Programme<br />

EDU - Entrepreneurship Development Unit<br />

ERS - Economic Recovery Strategy<br />

GDP - Gross Domestic Product<br />

GOK - Government of Kenya<br />

HRD - Human Resource Development<br />

ICEG - <strong>International</strong> Centre for Economic Growth<br />

ILO - <strong>International</strong> Labour Organization<br />

INT - <strong>International</strong><br />

KIA - Kenya Institute of Administration<br />

Ksh - Kenya Shillings<br />

MDI - <strong>Management</strong> Development Institute<br />

MRTTT - Ministry of Research, Technical Training and Technology<br />

MSE - Micro and Small Enterprises<br />

POP - Population<br />

SSE - Small Scale Enterprises<br />

TOF - Training of Facilitators<br />

TOT - Training of Trainers<br />

UNDP - United Nations Development Programme<br />

USIU - United States <strong>International</strong> University<br />

17

1.0 INTRODUCTION<br />

The mobilization of individual initiative to make better use of entrepreneurial talents in fostering economic<br />

development is a question that occupies all countries (Gibb, 1988; Khanka 2004). These countries in general<br />

and Kenya in particular regard entrepreneurs increasingly as an essential resource. Today, there’s enhanced<br />

awareness of entrepreneurship as a set of skills that needs to be taught and interest in finding out how<br />

entrepreneurs emerge and behave, factors that encourage enterprise creation and growth; and what can be done<br />

to promote entrepreneurship in Kenya a country with little business tradition. A wide range of factors<br />

contributes towards entrepreneurship. Chief among these has been its impact on socio-economic well being of<br />

the citizenry as the “engine of development” (GOK, 1992:1).<br />