Evidence Based Practice Symposium - McMaster University

Evidence Based Practice Symposium - McMaster University

Evidence Based Practice Symposium - McMaster University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

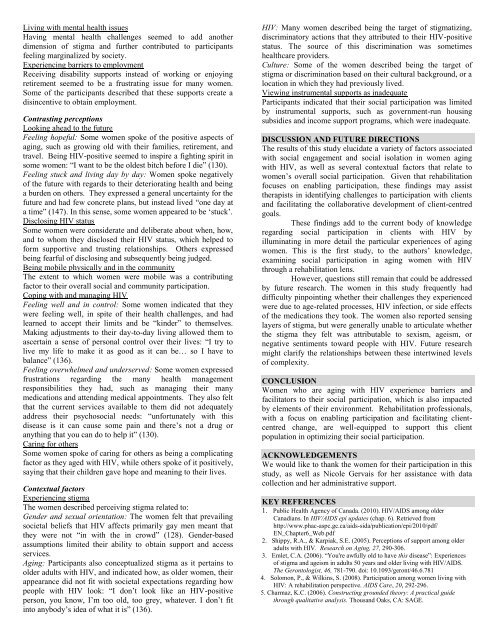

Living with mental health issues<br />

Having mental health challenges seemed to add another<br />

dimension of stigma and further contributed to participants<br />

feeling marginalized by society.<br />

Experiencing barriers to employment<br />

Receiving disability supports instead of working or enjoying<br />

retirement seemed to be a frustrating issue for many women.<br />

Some of the participants described that these supports create a<br />

disincentive to obtain employment.<br />

Contrasting perceptions<br />

Looking ahead to the future<br />

Feeling hopeful: Some women spoke of the positive aspects of<br />

aging, such as growing old with their families, retirement, and<br />

travel. Being HIV-positive seemed to inspire a fighting spirit in<br />

some women: “I want to be the oldest bitch before I die” (130).<br />

Feeling stuck and living day by day: Women spoke negatively<br />

of the future with regards to their deteriorating health and being<br />

a burden on others. They expressed a general uncertainty for the<br />

future and had few concrete plans, but instead lived “one day at<br />

a time” (147). In this sense, some women appeared to be ‘stuck’.<br />

Disclosing HIV status<br />

Some women were considerate and deliberate about when, how,<br />

and to whom they disclosed their HIV status, which helped to<br />

form supportive and trusting relationships. Others expressed<br />

being fearful of disclosing and subsequently being judged.<br />

Being mobile physically and in the community<br />

The extent to which women were mobile was a contributing<br />

factor to their overall social and community participation.<br />

Coping with and managing HIV<br />

Feeling well and in control: Some women indicated that they<br />

were feeling well, in spite of their health challenges, and had<br />

learned to accept their limits and be “kinder” to themselves.<br />

Making adjustments to their day-to-day living allowed them to<br />

ascertain a sense of personal control over their lives: “I try to<br />

live my life to make it as good as it can be… so I have to<br />

balance” (136).<br />

Feeling overwhelmed and underserved: Some women expressed<br />

frustrations regarding the many health management<br />

responsibilities they had, such as managing their many<br />

medications and attending medical appointments. They also felt<br />

that the current services available to them did not adequately<br />

address their psychosocial needs: “unfortunately with this<br />

disease is it can cause some pain and there’s not a drug or<br />

anything that you can do to help it” (130).<br />

Caring for others<br />

Some women spoke of caring for others as being a complicating<br />

factor as they aged with HIV, while others spoke of it positively,<br />

saying that their children gave hope and meaning to their lives.<br />

Contextual factors<br />

Experiencing stigma<br />

The women described perceiving stigma related to:<br />

Gender and sexual orientation: The women felt that prevailing<br />

societal beliefs that HIV affects primarily gay men meant that<br />

they were not “in with the in crowd” (128). Gender-based<br />

assumptions limited their ability to obtain support and access<br />

services.<br />

Aging: Participants also conceptualized stigma as it pertains to<br />

older adults with HIV, and indicated how, as older women, their<br />

appearance did not fit with societal expectations regarding how<br />

people with HIV look: “I don’t look like an HIV-positive<br />

person, you know, I’m too old, too grey, whatever. I don’t fit<br />

into anybody’s idea of what it is” (136).<br />

HIV: Many women described being the target of stigmatizing,<br />

discriminatory actions that they attributed to their HIV-positive<br />

status. The source of this discrimination was sometimes<br />

healthcare providers.<br />

Culture: Some of the women described being the target of<br />

stigma or discrimination based on their cultural background, or a<br />

location in which they had previously lived.<br />

Viewing instrumental supports as inadequate<br />

Participants indicated that their social participation was limited<br />

by instrumental supports, such as government-run housing<br />

subsidies and income support programs, which were inadequate.<br />

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS<br />

The results of this study elucidate a variety of factors associated<br />

with social engagement and social isolation in women aging<br />

with HIV, as well as several contextual factors that relate to<br />

women’s overall social participation. Given that rehabilitation<br />

focuses on enabling participation, these findings may assist<br />

therapists in identifying challenges to participation with clients<br />

and facilitating the collaborative development of client-centred<br />

goals.<br />

These findings add to the current body of knowledge<br />

regarding social participation in clients with HIV by<br />

illuminating in more detail the particular experiences of aging<br />

women. This is the first study, to the authors’ knowledge,<br />

examining social participation in aging women with HIV<br />

through a rehabilitation lens.<br />

However, questions still remain that could be addressed<br />

by future research. The women in this study frequently had<br />

difficulty pinpointing whether their challenges they experienced<br />

were due to age-related processes, HIV infection, or side effects<br />

of the medications they took. The women also reported sensing<br />

layers of stigma, but were generally unable to articulate whether<br />

the stigma they felt was attributable to sexism, ageism, or<br />

negative sentiments toward people with HIV. Future research<br />

might clarify the relationships between these intertwined levels<br />

of complexity.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Women who are aging with HIV experience barriers and<br />

facilitators to their social participation, which is also impacted<br />

by elements of their environment. Rehabilitation professionals,<br />

with a focus on enabling participation and facilitating clientcentred<br />

change, are well-equipped to support this client<br />

population in optimizing their social participation.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

We would like to thank the women for their participation in this<br />

study, as well as Nicole Gervais for her assistance with data<br />

collection and her administrative support.<br />

KEY REFERENCES<br />

1. Public Health Agency of Canada. (2010). HIV/AIDS among older<br />

Canadians. In HIV/AIDS epi updates (chap. 6). Retrieved from<br />

http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/epi/2010/pdf/<br />

EN_Chapter6_Web.pdf<br />

2. Shippy, R.A., & Karpiak, S.E. (2005). Perceptions of support among older<br />

adults with HIV. Research on Aging, 27, 290-306.<br />

3. Emlet, C.A. (2006). “You're awfully old to have this disease”: Experiences<br />

of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS.<br />

The Gerontologist, 46, 781-790. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781<br />

4. Solomon, P., & Wilkins, S. (2008). Participation among women living with<br />

HIV: A rehabilitation perspective. AIDS Care, 20, 292-296.<br />

5. Charmaz, K.C. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide<br />

through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.