AN OLD SPANISH TALE FROM ADD. MS. 14040, flf ... - British Library

AN OLD SPANISH TALE FROM ADD. MS. 14040, flf ... - British Library

AN OLD SPANISH TALE FROM ADD. MS. 14040, flf ... - British Library

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>AN</strong> <strong>OLD</strong> SP<strong>AN</strong>ISH <strong>TALE</strong> <strong>FROM</strong> <strong>ADD</strong>. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong>, <strong>flf</strong>.<br />

113r-114v: 'EXENPLO aUE ACAESgiO EN TIERRA<br />

DE DAMASCO A LA BUENA DUENNA CLIME^IA<br />

CON SU FIJA CLIMESTA QUE AVIA VEYNTE<br />

<strong>AN</strong>NOS E LA MEgiA EN CUNA'<br />

BARRY TAYLOR<br />

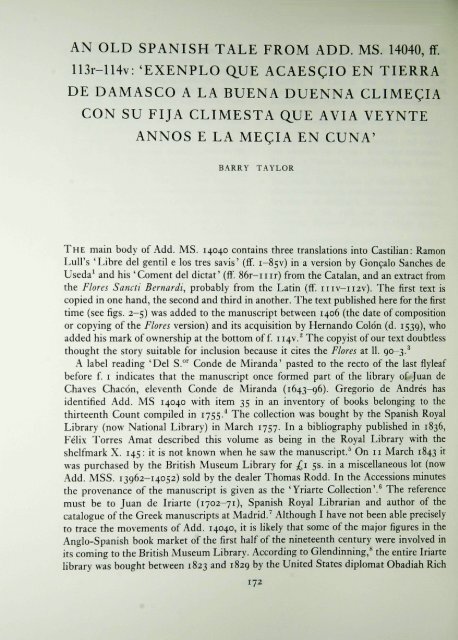

THE main body of Add. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong> contains three translations into Castihan: Ramon<br />

Lull's 'Libre del gentil e los tres savis' (ff. 1-85V) in a version by Gon^alo Sanches de<br />

Useda^ and his 'Coment del dictat' (ff. 86r-iiir) from the Catalan, and an extract from<br />

the Flores Sancti Bernardi, probably from the Latin (ff. iiiv-ii2v). The first text is<br />

copied in one hand, the second and third in another. The text published here for the first<br />

time (see figs. 2-5) was added to the manuscript between 1406 (the date of composition<br />

or copying ofthe Flores version) and its acquisition by Hernando Colon (d. 1539), who<br />

added his mark of ownership at the bottom off. ii4v.^ The copyist of our text doubtless<br />

thought the story suitable for inclusion because it cites the Flores at 11. 90-3.^<br />

A label reading 'Del S.^"^ Conde de Miranda' pasted to the recto ofthe last flyleaf<br />

before f. i indicates that the manuscript once formed part of the hbrary of Juan de<br />

Chaves Chacon, eleventh Conde de Miranda (1643-96). Gregorio de Andres has<br />

identified Add. <strong>MS</strong> <strong>14040</strong> with item 35 in an inventory of books belonging to the<br />

thirteenth Count compiled in 1755.'* The collection was bought by the Spanish Royal<br />

<strong>Library</strong> (now National <strong>Library</strong>) in March 1757. In a bibliography pubhshed in 1836,<br />

Felix Torres Amat described this volume as being in the Royal <strong>Library</strong> with the<br />

shelfmark X. 145: it is not known when he saw the manuscript.^ On 11 March 1843 it<br />

was purchased by the <strong>British</strong> Museum <strong>Library</strong> for £1 5s. in a miscellaneous lot (now<br />

Add. <strong>MS</strong>S. 13962-14052) sold by the dealer Thomas Rodd. In the Accessions minutes<br />

the provenance of the manuscript is given as the 'Yriarte Collection'.^ The reference<br />

must be to Juan de Iriarte (1702-71), Spanish Royal Librarian and author of the<br />

catalogue ofthe Greek manuscripts at Madrid.^ Although I have not been able precisely<br />

to trace the movements of Add. <strong>14040</strong>, it is likely that some ofthe major figures in the<br />

Anglo-Spanish book market ofthe first half of the nineteenth century were involved in<br />

its coming to the <strong>British</strong> Museum <strong>Library</strong>. According to Glendinning,^ the entire Iriarte<br />

library was bought between 1823 and 1829 by the United States diplomat Obadiah Rich<br />

172

(1783-1850) from 'a French officer married to the last surviving heir ofthe family';<br />

Thomas Thorpe was often his agent. Both Thorpe's and Rich's Spanish books were<br />

auctioned by Evans on 2 March and 4 July 1826 respectively. The connection between<br />

Thorpe, Rodd and the Iriarte collection is documented on 5 June 1826 when Thorpe<br />

sold Rodd 117 volumes from Iriarte's library which eventually passed via Richard Heber<br />

to the Bodleian. Thus, although the history ofthe ownership of Add. <strong>14040</strong> is far from<br />

complete, it seems unlikely that the manuscript was in the Biblioteca Real as late as 1836,<br />

the date of publication of Torres Amat's catalogue.<br />

Our text is called exenplo in the rubric which heads it, and indeed it displays the<br />

mixture of the didactic and the grotesquely sensational which characterizes one current<br />

within the exempluni genre. The plot may be summarized as follows. In Damascus during<br />

the reign of the fictional Emperor Sixtus, a noble lady Climegia and her daughter<br />

Climesta fall on hard times through the profligacy of their husband and father. The<br />

daughter, aged twenty (her age is given only in the rubric), is a worldling, proud ofher<br />

beauty. The women initially heed the exhortations of the hermit Patri^io against losing<br />

their souls for the sake of worldly gains. The hermit reinforces his admonitions with a<br />

brkfexemplum: Falsehood asked Truth where she might find her. Truth replied that if<br />

Falsehood found her, she should keep hold of her, as if she let her go she would never<br />

have her back.<br />

Mother, however, is advised by evil persons that the world will bring them all they<br />

need if she 'rocks' herself and her daughter. She accordingly buys two cradles, to no<br />

avail. A woman neighbour (the Devil in disguise) disabuses them: this 'rocking' is a<br />

euphemism for prostitution. They persevere in a life of vice despite Patri^io's warnings.<br />

Eventually Climesta is caught inflagrante and sentenced to be burned. On her way to the<br />

stake she asks to speak to her mother: when she draws near, the daughter bites off her<br />

tongue and puts her eyes out. Asked why, she says it is because she has been ruined by<br />

her mother's ill advice and failure to give her good counsel.<br />

Climesta's grotesque punishment ofher mother is an example of a tale found in many<br />

didactic texts.^ Probably the oldest version known is in the Greek Aesop :^^ a boy steals<br />

a book from a schoolmate as a joke. His mother laughs at his prank, which encourages<br />

him to go on to worse crimes. Eventually he is sentenced to be hanged; on the way to<br />

the scaffold, under pretence of whispering to his mother, he bites off her ear (see fig. i).<br />

He explains his action by saying that her indulgence was the cause of all his crimes: had<br />

she punished him at his first offence, he says, he would never have come to such a pass.<br />

The Aesopic text seems not to have entered Latin circles until Rinuccio d'Arezzo's<br />

1448 translation. The version in Pseudo-Boethius, De disciplina scolarium, dated circa<br />

1240, was known earher, and more widely, to the Latins: several manuscripts have<br />

English and French glosses, suggesting that they were used for teaching grammar.^^<br />

There Lucretius, son of Zeno,^^ wastes the advantages of good birth, talent and<br />

patrimony on prostitutes. His father stands by ('patre poenam deferente'). The youth<br />

turns to crime to pay his debts, and is saved from crucifixion because his father bribes<br />

the authorities. Finally father can pay no more. On the way to execution the son bites<br />

173

Fig. I. The errant son bites his mother's ear. Libro delsabio £5" clarissimo fabuladorysopo hystoriad<br />

£5' annotado (Seville: Cromberger, 1526). C.59.i.i6, f. clvi""<br />

Text<br />

Aesop (see fig. i)<br />

Odo of Cheriton'^<br />

Ps-Boethius<br />

Jacques de Vitry^*<br />

Etienne de Bourbon'^<br />

Libra del caballero<br />

Spanish woodcut*'<br />

Climefia<br />

TABLE L VARI<strong>AN</strong>TS<br />

Dale<br />

c. 1220<br />

c. 1240<br />

d. 1240<br />

d. 1261<br />

Parent<br />

Mother<br />

Father<br />

Father<br />

Father<br />

Father<br />

Mother<br />

^- 1303<br />

1488<br />

Mother<br />

copied post 1406 Mother<br />

OF THE CLIMEgiA STORY<br />

Child Crime Punishment Bitten<br />

Son<br />

Son<br />

Son<br />

Son<br />

Son<br />

Son<br />

Stealing<br />

Hanging<br />

Stealing, immorality Hanging<br />

Fornication Crucifixion<br />

Stealing<br />

Hanging<br />

Stealing<br />

Stealing, etc.<br />

Hanging<br />

Son —<br />

Daughter Fornication<br />

Burning<br />

Eai'<br />

Flesh of face<br />

Nose<br />

Lips<br />

Nose<br />

Lips<br />

Nose<br />

Tongue, eyes<br />

off his father's nose. His last words blame first his father's indulgence and then his own<br />

disobedience: 'Why did I escape unpunished from my first errors.? Why did I not obey<br />

my first teacher and despise my fellows.^' In subsequent derivatives of this story, the<br />

protagonists, crime, punishment and mutilation differ, as is shown in Table i.<br />

It will be seen from the Table that the story in Add. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong> does not correspond<br />

174

in all particulars with any other known version. One feature of our texts is the feminine<br />

element: the child is a daughter who engages in prostitution rather than a son who<br />

consorts with prostitutes. The inclusion of a daughter enables the author to descant on<br />

the theme of women's vanity (11. 17-22): Chmesta from the start is guilty of excessive<br />

care for her appearance - a theme beloved of medieval preachers - and although the<br />

connection between female luxury and prostitution is not made explicit, they are<br />

certainly referred to in similar terms: see 11. 13-15.<br />

Patrigio's tale ofthe exchange between Truth and Falsehood is not unique to this text,<br />

although it has fewer parallels than the main story. The only close analogue is in the Libra<br />

del caballero Zifar of circa 1303.^^ When Wind, Water and Truth part company, they ask<br />

each other where he is to be found. Water says he will be in the fountains. Wind in the<br />

mountain passes. Truth replies: 'Keep me while you have me, as once you let me go<br />

you'll never catch me again.' The version in Zifar is superior to that in our manuscript,<br />

as it integrates Truth's answer into a tripartite structure in which Truth is declared even<br />

harder to keep hold of than the ungraspable Wind and Water. It is interesting that the<br />

only work to include both the stories in our text appears also to be an Old Spanish one.<br />

The immediate source of our text is unknown, but it seems likely that it is a<br />

translation, partly because one episode is built around a pun on mefer, 'to rock in a<br />

cradle/be a prostitute.' The pun is unique to this version. The second meaning of mefer<br />

is not to my knowledge attested in Old Spanish, although it does exist in modern<br />

Portuguese mexer}^ In Latin however the sexual meaning of miscere (the supposed<br />

etymon of mefer) is well established.^*' The text shows some signs that it is a fragment.<br />

The first three sentences refer not only to Climegia and her daughter Climesta but also<br />

to Clime^ia's sister Gloriana and her son Picleco. Parents are exhorted to learn from<br />

'these two sisters,' which suggests that an earher witness preserved a parallel story,<br />

perhaps a tale of virtue rewarded. However, in the extant text no more is heard of<br />

Gloriana and Picleco.<br />

EDITION OF THE TEXT IN <strong>ADD</strong>. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong><br />

[f. ii3r] Exenplo que acaes^io en tierra de Damasco a la buena duenna Climefia con su<br />

fija Climesta que avia veynte annos e la megia en cuna.<br />

En la ^ibdat de Damasco en tienpo del enperador Systo, andando en aquellas partes<br />

mucha justi^ia, acaes^io a una buena duenna que avia por nonbre Climefia que ovo una<br />

fija de su marido; que ovo por nonbre Climesta Tuburgia porque a su padre llamaron<br />

por nonbre Gofrido Tiburgio. E era esta duenna hermana de otra duenna a que llamavan<br />

Gloriana, que tenia un fijo que avia nonbre Picleco. Aqui vengan los padres e las niadres<br />

que an de castigar fijos e fijas e ayan enxenplo en estas dos hermanas e veredes que les<br />

Asy que fue que seyendo Climesta bien criada de los saberes e costunbres del mundo<br />

e muy poco mostrada en sabiduria de las virtudes, del temor de Dios muy menguada,<br />

175

acaes^io que la fija seyendo toda de voluntad mundanal, deseadora de los bienes<br />

falle9ederos mundanos, deseo bien apostarse por dar pares^er de su fermossura terrenal<br />

mortal a los omes desventurados que la avian de mirar; con la qual rred y ansuelo el<br />

15 Diablo posia mas almas que con otra cosa de pecado.<br />

jA! jGuay de las mesquinas mugeres! iQue cuenta daran a Dios de todas las cobdigias<br />

que fasen venir a los omes de pecado mortal? Que por tomar forma annadida de afeytes<br />

pierden ssu alma. Et al dia santo del domingo o fiesta sse paran a las puertas non con<br />

enten^ion de sservir a Dios mas al Diablo, que es su sennor, dexando la forma que Dios<br />

20 les dio liana et buena, y tomando forma del Diablo a quien sirven, pelando los cabellos<br />

del rrostro e blanqueando las carnes con colores diversos, todo a fyn de luxuriar y dar<br />

fartura a ssu carne e induzir los cora9ones a pecado. Qiertamente mas les valdria la<br />

muerte que non el tal acre^entamiento de pecados, ca de todas aquellas ocasiones daran<br />

cuenta a Dios. E sy aqui non sso creydo, el dia de los tenblores de aquel juysio espantoso,<br />

25 que seran manifiestos todos los pecados de cada pecador a Dios y a los angeles e santos<br />

y Santas & a los diablos e a todos, me creeran.<br />

Asy fue que eran mugeres fijasdalgo e, por causa que los maridos que ovieron fueron<br />

desgastadores y de malos rrecaudos, vinieron en pobredat. E pasando por algund tienpo<br />

estrechamente, vinieron a sse encomendar a un ome eclesiastico del qual rrescebieron<br />

30 buenos desires e alguna consolacion. E commo la cobdi^ia non siente fartura, entraron<br />

penssamientos en la madre e en la fija que via ternian desta vida presente e acordaron de<br />

lo desir a aquel ome bueno que las consolava e dixieron [f. //ju] que estavan en grand<br />

tribulation por mester e non poder conplir lo que querian.<br />

Et el buen ome dixoles, 'Fijas, muy muchas cosas vos tengo de rresponder en esto.<br />

35 Avedes de ssaber que Dios todos los omes e mugeres del mundo egualo en salir de la<br />

tierra desnudos & yr a la tierra desnudos. & esto por que connosca ser todas las cosas<br />

desta vida mierda & cosa cayda. & demas quiso el ser mas pobre, & su madre & sus<br />

apostoles, de tal pobredat que ninguna cosa non toviese & esta pobredat que fuese en el<br />

alma & dixo "Bienaventurados los pobres de spiritu, que dellos es el rreyno de los 9ielos"<br />

40 & dixo ma[s] " iQue aprovecha a ninguno ser sennor de todo el mundo sy su anima aya<br />

de perder?" Mas valdria non ser nasgido. Esta pobredat loo & amo ca la sennal de<br />

perdition esta es: non recontentar nin aver pa9ien9ia con lo que tiene. Ca saber devedes<br />

que ninguna criatura non ha aqui syno Io que Dios le quiere dar & commo non sse<br />

contente luego torna contra Dios: quanto mas quel Nuestro Salvador nos dixo en exenplo<br />

45 que Dios a los que ama sigue aqui con persecu^iones por dalles la su gloria sy<br />

perseveraren.'<br />

& despues que les dixo estas cosas y otras muchas & vido que non [se] davan a lo que<br />

se devian dar, dixoles, 'Amigas, la Verdat & la Mentira fisieron conpannia muy grand<br />

tienpo. & quando se partieron dixo la Mentira a la Verdat que donde la fallaria. Dixole<br />

50 la Verdat que quando la toviese que fisiese en guisa que nol saliese de mano, que sy una<br />

ves la perdia que nunca la cobraria.' & que entendiesen este dicho: que sy non<br />

guardava[n] lo que les era dado de honestidat de bien dellas ^ del que non curasen del,<br />

porque el pecado de sobervia y descono^imiento de bienfecho sienpre fue vengado por<br />

176

Dios. & espidiose dellas prometiendoles su consolacion sy guardasen lo que devian<br />

guardar.<br />

El Diablo, que nunca dexa de perseguir a los que bien quieren bevir, ca aquel es su<br />

ofi^io, pusoles en cora9on que tomasen abito honesto por que de diuso de aquel abito<br />

cupiese toda disolu9ion y pecado. E acaes9io qut fiandose a personas non buenas fue dado<br />

consejo a la madre que sienpre se me9iese; que despues, que meciese a su fija; e que asy<br />

me9iendose quel mundo traheria lo suyo. La buena muger conpro dos cunas & echose<br />

en la una & a su fija en la otra, continuando el meger. & duro esto 9iertos meses & veyendo<br />

la madre que non venia nada, torno a fablar do la buena consejera que fiso lo que le dixo<br />

e que non venia cosa de provecho. E ella dixo, 'Yo yre a vuestra casa y lo vere commo<br />

lo fasedes.'<br />

& quando la buena muger vido las cunas & vido que non la avian entendido, dixo,<br />

'Amiga, non [es] este tal me9er commo yo te dixe, ca el otro me9er es de otra manera,<br />

segund que te agora dire. Sabe que tu te as de vestir G dt[f. 114] afeytar en tal guisa que<br />

los que te vieren a ti adere9ada & so abito honesto que non pongan culpa a tu fija que<br />

faga mas que tu pues es mas mo9a. & ternas esta manera: todos los dias que pudieres,<br />

anda todos los lugares sennalados ca asy andando apregonas tu vino, que quien dello<br />

quisiere que trayga jarro e dinero, que non se da de balde. & ternas estas condi9iones<br />

que son caudal de conplir todos tus deseos: despues de comer guardaras en todos los<br />

dias que pudieres la puerta de la caWe fixa mucho bien adere9ada; lo segundo, miraras bien<br />

en fito a todas las personas que por y passaren; lo tercero busca ocasiones por que fables<br />

con los que tu ovieres voluntad que te conosca[n]; lo quarto, quando les fablares fasles<br />

gesto amoroso, que entiendan que non les denegaras cosa ninguna de lo que te fuere bien<br />

pagado; lo quinto, fierelos de tus saetas, que les pases el cora9on [con] palabras tales que<br />

aduro dexes habito honesto los declares que presta estas; et con mucho sosiego verna toda<br />

gente a tu casa. & non guardes lealtad en desir que Dios al ssennor de casa se quiere<br />

servir. & segund te fallares dimelo.' & fuese el Diablo que tomava figura de muger<br />

veyendo que se le queria dar.<br />

Et siguiendo este camino vino esto a noti9ia del su amigo padre espiritual. Et fue ver<br />

sy esto sy era verdat & desque vido el fecho dispidiose dellas dissiendo quel Diablo las<br />

avia engannado ca grand peligro avian de aver. Et por ver sy las podria tornar a buen<br />

camino dixoles asy,' La vuestra via es de ydolo & de mal que ya vos lo ove dicho: ay bien,<br />

mejor & mas mejor & ay mal e peor & mas peor. & en esto estades vosotras que non<br />

solamente pecades mas millares de pecados a otros fasedes faser. Ca aunque mal &<br />

pecado quisiesedes faser fuese en un grado menor & non por tal via nin manera de Io qual<br />

a mi pues aqui vengo & tales estades no se puede escusar que por vuestro malestar non<br />

se siga mal. Ca commo la batalla de todos los buenos, segund dise Sant Bernaldo, es que<br />

vea el que bive sus pensamientos. E que commo el linage de los spiritus sea de muchas<br />

maneras Etl alma, que es spiritu, connos9e las tenta9iones del spiritu que son tres spiritus<br />

que tientan de buena manera: de la carne en bever & comer & fablar y oyr y oler y tocar<br />

y andar a luxuria & yra & enbidia y vanagloria y sobervia & peresa y gula & tristesa &<br />

pesar y otras cosas de carne; y el es[piritu] del mundo trahia de mugeres & bien<br />

177

aconpannado y bien honrrado y bien vestido & bien adere9ado de casas & tierras y otras<br />

cosas tales; & el ter9er es el serpiente amigo nin enemigo que de enbidia se muere.<br />

'Et \f. iJ4v] Climesta fija ique eres? La sennal a que todos diran que de [. .] muerta<br />

quel tienpo que tovieres otorg^do de la naturalesa te durare que te ayan de dar algo los<br />

100 omes que llamares de cada dia. E llamertas fasta que te dexen por baldia & desaventurada<br />

que non sera mas de quanto sseas conos9ida que vendes fruta: ca luego la fruta de la<br />

9iruela quando entra vale una un maravedi y despues valen 9iento por un maravedi, asy<br />

es de ty commo fue de las otras tales commo tu, que quando comien9an el ofi9io nuevo<br />

por la novedat an algo & despues vienen al segundo ofi9io de los tres ofi9ios de la buena<br />

105 muger y despues al tercero: los quales son puta en mancebia y puta y alcahueta & en rafes<br />

alcahueta. Fija, por me dessa dia de oy. Pues tu camino es tal qual tu te lo quieres y tu<br />

madre te lo conseja. Sabe quel que vien quiere vivir a de perder su alma y el mundo por<br />

Dios y fallar lo ha & a se de perder a lo menos aunque biva mal en esta manera: que ande<br />

muy honestamente en este mundo en bevir y traher [honestas] rropas y muy llano rrostro<br />

no & muy baxos los ojos; quando algo le dixeren muy honesto rresponder; y syn destos<br />

ningunos & que de ty aver quieras algo faser non des lugar a pecado que diga que tu<br />

madre te lo trahe todo y tu que te lo quieres aunque trabajo por vosotras que sso p[..]<br />

que vos agora a Dios vos tncomtendo, quel mundo que servis vos dara galardon,'<br />

Fuese Patri9io que era v[...]s hermitanno de Clime9ia [&] Climesta su fija las quales<br />

115 seguiendo ssus vanos pensamientos dando su fermos[ur]a a muchos cucubitos, fasiendose<br />

conos9er con muchos. Lo que con mal se gana con mal se acaba: viniendo poco tienpo<br />

que usavan non devidamente, fue tomada Climesta con un onbre contra l[e]y y fue dada<br />

sentencia que fuese quemada y coidando ya entre si y veiendo quel davan la muerte por<br />

culpa de su madre, Uevandola a matar y yendo Patri9io tras ella por ver que 9ima y<br />

120 acabamiento avria del fecho de las que tanto amo, yendo la madre en pos ella dixo & pidio<br />

li^en^ia que la dexasen fablar a su madre Climesta. Et llegarongela & por juysio divinal<br />

comiole las narises et quebrole los ojos. & pescudaronle por que lo fisiera. Bixo que<br />

porque ella le consejo lo que fiso por mucha ganan9ia, et que ge lo pudiera estorvar sy<br />

bien la castigo. & despues Climesta y el c[. .]je fueron quemados. Et asy acabaron: Dios<br />

125 les aya mer9ed & amen.<br />

Edttorial criteria: editorial additions are in brackets [ ]. Points within brackets [..] indicate<br />

illegible passages, the number of points approximating the number of unreadable letters. Italics<br />

indicate a doubtful reading.<br />

Textual notes: numbered line references are to this edition and not to the manuscript.<br />

13 deseo] <strong>MS</strong> deseando 20 les] lo 27 causa que] causa de 32 dixieron] dixo<br />

33 mester corrected from menester 37 vida] v. que son 42 devedes] deve 59 madre<br />

que] m q q 71 quisiere] qsiere 74 passaren] passaron 78 aduro dexes] duso defe?<br />

81 queria] querian queria 88 quisiesedes] qsieseds 89 malestar] malestan(?) 94<br />

andar a] andar y 96 de] y 97 el ter9er] ost9er(?) 105 puta] puta \en mocedat puta/<br />

107 vivir] vender(?), 115 seguiendo] seguiendos 118 coidando ya entre si] co[. .] ya<br />

e[.]t[.]s[.]<br />

178

?%. "^-..<br />

?»i.^,4..pf-'f*ij!tff:<br />

2. Add. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong>, f. ii3r<br />

179<br />

^1 ^at> Iti'-*

4U<br />

;<br />

Fig. J. Add. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong>, f. 113V<br />

180<br />

ns<br />

Vfr

\l '<br />

• *•'..,<br />

(lift*<br />

U<br />

. Add. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong>, f.<br />

181<br />

/.:

i'<br />

"-'5? v- T^in...-<br />

Ftg. s- Add. <strong>MS</strong>. <strong>14040</strong>, f. 114V<br />

182<br />

i<br />

ny )„.

Exegetical notes: 28 de malos rrecaudos: spendthrift: cf. 'costosas o de malos recabdos', Castigos<br />

y doctrinas que vn sabio daiia a sus hijas, in Hermann Knust (ed.), Dos obras diddcticasy dos leyendas<br />

sacadas de manuscritos de la Biblioteca del Escorial (Madrid, 1878), pp. 249-93, at p. 285 39<br />

Mt. 5.3 40-1 Mt. 16.26; Mk. 8.36 41 loo £5* amo. The reading is difficult, but may be<br />

a synonymous pair: cf. 'honrats e loats e amats': Ramon Llull, Llibre de Porde de cavalleria, ed.<br />

Albert Soler i Llopart (Barcelona, 1988), p. 237, line 145. 45-6 Cf. Mk. 10.30; Mt. 5.10<br />

70 vino. Prostitutes often plied their trade under the cover of wine-selling. The branch, symbol<br />

ofthe wine trade, came to denote prostitution; hence Spanish ramera: see Diego Hurtado de<br />

Mendoza, Poesi'a completa^ ed. Jose Ignacio Di'ez Fernandez (Barcelona, 1989), p. 509, note to<br />

poem clxxi 73 la puerta de la calle: contrast ' para ser honestas, que no vos asentedes a las<br />

ventanas ni...a las puertas' {Castigos, p. 282). Prostitutes in nineteenth-century Madrid referred<br />

to their trade as 'hacer puerta': see Javier Rioyo, Madrid: casas de lenocinio, holganzay malvivir<br />

(Madrid, 1991), p. 326 73-4 fniraras bien en fito: in contrast with the modestly downcast gaze<br />

of 1. no 85 ydolo. The connection between cosmetics and idols is made in other didactic<br />

texts: cf. ' Asi lo dize Sant Pablo en la primera canonica a los 9inco capitulos, en que dize que las<br />

mugeres non trayan... vestiduras desonestas, nin pintar las caras como ydolos de diablo', Frank<br />

Anthony Ramirez (ed.), Tratado de la comunidad (London, 1988), p. 126; and * Estas que asi se<br />

visten y se precian del traer, dice el santo profeta e rey David, que son semejantes a los ldolos e<br />

imagenes de los templos', Hernando de Talavera, De vestir y de calzar, in Miguel Mir (ed.),<br />

Escritores mi'sticos espafioles, vol. i, Nueva Biblioteca de Autores Espaiioles, xvi (Madrid, 1911),<br />

p. 68. (I have not been able to identify the Biblical references) 90 Sant Bernaldo. Cf. 'el<br />

linaje de los spiritus son diversos e departidos' 'del spiritu humano, que es el alma del omne',<br />

'An Old Spanish Translation from the Flores Sancti Bernard^ cited in n. 2, sentences 1-2. Much<br />

of this chapter of St Bernard is concerned with the spirits of the flesh, of the world and of the<br />

Devil (especially §9), which are discussed by the present text at lines 93 (carne), 95 (mundo)<br />

and 97 (serpiente) 104-5 ^os tres offios de la buena muger. The text originally gave three stages<br />

in the career ofthe loose woman: 'whore in youth', ' whore-cum-procuress' and 'vile procuress'.<br />

The interlinear addition precedes these with an earlier stage 'whore in girlhood'. Mancebia had<br />

two meanings: the age of sexual maturity (say 14-40), preceded by mocedat (childhood up to<br />

about 14). The precise distribution of years differs from author to author, but the order is always<br />

the same: see John K. Walsh (ed.). El libro de los doze sabios (Madrid, 1976), p. 27. Mancebia by<br />

extension could also mean prostitution: the Diccionario de autoridades of 1726 translates mancebia<br />

as 'prostibulum.' It is likely that the original intention in our text was to denote youth in general;<br />

the glossator felt the need to split the concept into earlier and later periods 107 a de perder<br />

su alma: cf. Mt. 10.39, ^*^^- ^^^ -^^ ?"^ "^^^ "^^^ ^^ gana con mal se acaba: probably a<br />

proverb: cf. 'Quien en mal anda, mal acaba', Felipe C. R. Maldonado (ed.), Refranero cldsico<br />

espanol (Madrid, 1982), p. 61, no. 211, and Eleanor S. O'Kane, Refranes y frases proverbiales<br />

espanolas de la edad media (Madrid, 1959), p. 150 118 que fuese quemada. The final scene of<br />

this story takes place at the stake. Burning as punishment for prostitution is both a historical<br />

reality and a favourite motif of didactic fiction: see the fourteenth-century Fuero de Albarracin,<br />

cited by D. J. Gifford and F. W. Hodcroft, Textos lingtitsticos del medioevo espafiol (Oxford, 1959),<br />

p. 191 124 castigo: the slightly irregular syntax is paralleled in Manrique's 'este mundo<br />

bueno fue/si bien usasemos del': Coplaspor la muerte de su padre, 61-62, in his Poesi'a, ed. Jesiis-<br />

Manuel Alda Tesan (Madrid, 1977), p. 147.<br />

183

I am grateful to Professors Dwayne E. Carpenter<br />

and David Hook for procuring three bibliographical<br />

items.<br />

1 On the translator, see Manuel Nieto Cumplido,<br />

'Aportacion historica al Cancionero de Baena\<br />

Historia, Instituciones, Docunientos, vi (1979), pp-<br />

197-218, at pp. 199-201.<br />

2 I have corrected some assertions which I made in<br />

'An Old Spanish Translation from the Flores<br />

Sancti Bernardi in <strong>British</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Add. <strong>MS</strong>.<br />

<strong>14040</strong>, fF. iiiv-ri2v', <strong>British</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Journal,<br />

xvi (1990), pp. 58-65, in the light of Fernando<br />

Dominguez Reboiras, 'El Content del dictat de<br />

Ramon Llull: una traduccidn castellana de<br />

principios del siglo XV', in Studia in honorem<br />

prof. M. de Riquer, vol. i (Barcelona, 1991), pp.<br />

169-232. The manuscript has also been described<br />

in Brian Dutton (ed.). El cancionero<br />

del siglo XV, vol. i (Salamanca, 1990), p. 372<br />

and in Ramon Llull, Llibre del gentil e dels<br />

tres savis, ed. Anthony Bonner, Nova edicio de<br />

les obres de Ramon Llull, ii (Palma, 1993),<br />

pp. xxix-xxx. I have not seen Herbert R. Stone,<br />

' A Critical Edition of the Libro del gentil e de los<br />

tres sabios [Castilian Text]\ Ph.D., University<br />

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1965. (I am<br />

grateful to Prof. Bonner for the latter two<br />

references.)<br />

3 A parallel case of such a criterion for inclusion is<br />

the liturgical play the Auto de los Reyes Magos,<br />

added to a manuscript of commentaries on<br />

Jeremiah because it makes a passing reference to<br />

the prophet: see Julian Weiss, 'The Auto de los<br />

Reyes Magos and the Book of Jeremiah', La<br />

Coro'mca, ix: 2 (Spring 1981), pp. 128-31.<br />

4 Gregorio de Andres, 'Los codices del Conde de<br />

Miranda en la Biblioteca Nacional', Revista de<br />

Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos, lxxxii (1979), pp.<br />

611-27.<br />

5 Torres Amat, Memorias para ayudar aformar un<br />

diccionario critico de los escritores catalanes<br />

(Barcelona, 1836), p. 706.<br />

6 I am grateful to Julian Conway for consulting<br />

the Accessions minutes for me.<br />

7 Regiae bibliothecae matritensis codices manuscripti<br />

(Madrid, 1769). On Iriarte, see his Obras sueltas<br />

{Madrid, 1774), edited with an introductory<br />

study by Bartolome de Iriarte; J. M. Fernandez<br />

Pomar, 'Don Juan de Iriarte bibliotecario de la<br />

Real Biblioteca', Bibliothek und Wissenschaft, iii<br />

(1966), pp. 113-44; ^""^ Gregorio de Andres, 'El<br />

bibliotecario D. Juan de Iriarte', in Homenaje a<br />

Luis Morales Oliver (Madrid, 1986), pp.<br />

587-606.<br />

8 Nigel Glendinning, 'Spanish Books in England,<br />

1800-1850', Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical<br />

Society, iii (1959-63), pp. 70-92, at<br />

pp. 79-80, 86.<br />

9 They are listed in Paul Meyer, 'L'Enfant gate<br />

devenu criminel', Romania, xiv (1885), pp.<br />

581-3; Stith Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-<br />

Literature (Copenhagen, 1955-7), no. Q586;<br />

Frederic Tubach, Index exemplorum (Helsinki,<br />

1969), no. 3488; Rameline E. Marsan, Itineraire<br />

espagnol du conte medieval, VIIF-XV^ siecles<br />

(Paris, 1974), pp. 400-4; Jose Fradejas Lebrero,<br />

'El mas copioso ejemplario del s. XVI' [The<br />

Fructus sanctorum of Alonso de Villegas], Homenaje<br />

a Pedro Sdinz Rodriguez (Madrid, 1986),<br />

vol. ii, pp. 229-49 ^t p. 245; Maxime Chevalier,<br />

'El Libro de los exenplos y la tradicion oral',<br />

Dicenda, vi (1987), pp. 83-92, at p. 17; Ed<br />

Brown, 'The Motif of the Cut-Off Nose in<br />

Medieval Spanish Literature', ^n>/(Lexington,<br />

Ky), vi (1989), pp. 12-18; and Victoria A.<br />

Burrus and Harriet Goldberg (eds.), Esopete<br />

ystoriado {Toulouse 1488) (Madison, 1990), pp.<br />

112, 117, n. 14; Juan Manuel Cacho Blecua,'La<br />

crueldad del castigo: el ajusticiamiento del<br />

traidor y la "pertiga" educadora en el Libro del<br />

cavallero Zifar\ in Violenciay conflictividaden la<br />

sociedad de la Espana bajomedieval {Aragon en la<br />

Edad Media : sesiones de trabajo, IV Seminario de<br />

Historia Medieval) (Saragossa, 1995), pp. 59^89,<br />

at pp. 74-83.<br />

10 The story is no. 200 in the Augustana recension,<br />

compiled in the ist or 2nd century A.D. : see Ben<br />

Edwin Perry (ed.), Babrius and Phaedrus<br />

(London, 1965), p. 459. Rinuccio's translation<br />

circulated widely as part ofthe expanded Aesop<br />

edited by Heinrich Steinhdwel (Ulm: Johann<br />

Zainer, 1476 or 1477): see the Old Spanish<br />

version, Esopete ystoriado (as in n. 9) and R. T.<br />

Lenaghan, 'Steinhowel's Esopus and Early Humanism',<br />

Monatshefte fur Deutschen Unterricht,<br />

Deutsche Sprache und Literatur, Ix (1968), pp.<br />

1-8. The Aesopic version is used by J. L. Vives,<br />

De iiistitutione feminae christianae (1523), Book ii,<br />

chapter xxix: see Libro llamado Instrucion dela<br />

muger christiana, tr. Juan Justiniano (Valencia,<br />

1528), f. lxxxii^^<br />

11 Pseudo-Boece, De disciplina scolarium, ed. Olga<br />

Weijers (Leiden, 1976), ii, §8-10, pp. ioi~2. For<br />

the glosses, see Tony Hunt, Teaching and

Learning Latin in Thirteenth-Century England, i<br />

(Cambridge, 1991), pp. 74, 86, i6of. Although<br />

Weijers does not cite any Hispanic witnesses, the<br />

Disciplina was known in Spain: see Saragossa<br />

Cathedral <strong>MS</strong>. 15-58 and Barcelona, Biblioteca<br />

de Catalunya, <strong>MS</strong>. 559 (book i only). There are<br />

also references in inventories: see Gabriel<br />

Llompart,' El lhbre catala a la casa mallorquina',<br />

Analecta Sacra Tarraconensia, xlviii {1975), pp.<br />

193-240; xlix-1 (1976-77), pp. 57-114, at p. 72<br />

(citing a Majorcan inventory of the fifteenth<br />

century) and Manuel Jose Pedraza Garcia,<br />

Documentos para el estudio de la historia del libro<br />

en Zaragoza entre 1501 y 1521 (Saragossa, 1993),<br />

p. 65 (a Saragossa inventory of 1503). Further on<br />

the Spanish reception of Ps-Boethius, see Francisco<br />

Marquez Villanueva, 'La Celestina y el<br />

pseudo Boecio De Disciplina scolarium', in E. M.<br />

Gerli and H. L. Sharrer (eds.), Hispanic Medieval<br />

Studies in Honor of Samuel G. Armistead<br />

(Madison, 1992), pp. 221-42. The Disciplina is<br />

quoted very closely by John of Wales, Communiloquium<br />

(Strassburg, 1489; <strong>British</strong> <strong>Library</strong>,<br />

IB.2012), sig. f2'-f3'': for example, he includes<br />

the names ofthe protagonists. Other texts which<br />

cite the Disciplina as their source do not follow it<br />

in such detail and it is possible that they use the<br />

Disciplina via the Commumloquium: see the<br />

Speculum laicorum, ed. J.-Th. Welter (Paris,<br />

1914), no. 296, p. 61, ch. 38; its Spanish<br />

derivative the Especulo de los legos, ed. J. M.<br />

Mohedano {Madrid, 1951), no. 287, ch. 42, pp.<br />

196-7; and the first redaction of Castigos e<br />

documentos del rey don Sancho, in P. de Gayangos<br />

(ed.), Escritores en prosa anteriores al siglo XV,<br />

Biblioteca de autores espanoles, Ii {Madrid,<br />

i860), p. 90.<br />

12 Curiously, Zeno himself was the protagonist of a<br />

story in which, on the cross, he bit off the nose<br />

of his persecutor: see John of Wales, Breviloquium,<br />

part iv, ch. iii, in Summa Johannis<br />

Valensis de regimine vite humane... {Lyons, 1511),<br />

f. ccxiiij'".<br />

13 Odo of Cheriton, Parabolae, in L. Hervieux<br />

(ed.), Les Fabulistes latins, vol. iv (Paris, 1896),<br />

no. 133, p. 316.<br />

14 T. F. Crane (ed.). The Exempla or Illustrative<br />

Stories from the ^ Sermones vulgares^ of Jacques de<br />

Vitry (London, 1890), p. 121, no. 287, p. 259.<br />

185<br />

15 Etienne de Bourbon (d. 1261), Tractatus de<br />

diversis materiis predicabilibus. Book i, De dono<br />

timoris, in A. Lecoy de la Marche (ed.). Anecdotes<br />

historiques legendes et apologues tire's du recueil<br />

ine'dit d^Etienne de Bourbon (Paris, 1877), no. 43,<br />

pp. 51-2. Etienne is the source for Humbert of<br />

Romans (d. 1277), De dono timoris: see J.-Th.<br />

Welter, VExemplum dans la litterature religieuse<br />

er didactique du Moyen Age (Paris, 1927), pp.<br />

215, 224—8. The De dono timoris is a source for<br />

the Alphabetum narrationum of Arnold of Liege<br />

(d. 1345), according to Welter, p. 312. The Latin<br />

text of the Alphabetum is still unpubhshed, but<br />

see the Catalan and English translations: Recull<br />

de eximplis e miracles, ed. M. Aguilo y Fuster<br />

{Barcelona, 1881), vol. i, no. 185, p. 169; An<br />

Alphabet of Tales, ed. M. M. Banks {London,<br />

1904), no. 217, p. 152. The same configuration of<br />

motifs occurs in the versions of the story given<br />

by Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum morale. III, iii,<br />

7 {Douai, 1624), p. 1015; Clemente Sanchez de<br />

Vercial, Libro de los exemplos por a.b.c; in<br />

Gayangos (ed.), Escritores en prosa (as in n. 10),<br />

p. 513, no. 273; and Philippe of Novare, Les<br />

Quatre temps d'dge de thomme, ed. M. de Freville<br />

(Paris, 1888), pp. 161-4.<br />

16 J. Gonzalez Muela (ed.), Libro del caballero Zifar<br />

(Madrid, 1982), pp. 252-56; for the illustration<br />

of this story in Paris, Bibhotheque nationale,<br />

<strong>MS</strong>. Esp. 36, see John E. Keller and Richard<br />

P. Kinkade, Iconography in Medieval Spanish<br />

Literature (Lexington, Ky, 1984), pp. 68-70.<br />

17 The editors of the Spanish text (cited in n. 9)<br />

note that while a woodcut in the Spanish editions<br />

of 1489 and 1496 shows the son biting his<br />

mother's ear, as in the text, the illustration in the<br />

Spanish edition of 1488 shows him biting her<br />

nose: this represents a combination of motifs not<br />

found to my knowledge in the written witnesses.<br />

18 As in n. 16, pp. 394-5. Charles Philip Wagner,<br />

'The Sources of El Cavallero Cifar\ Revue<br />

Hispanique, x (1903), pp. 5-104, at p. 77, gives<br />

some parallels. The closest is in Straparola, who<br />

does not however have the same punch-line.<br />

19 Sergio Augusto, Este mundo e um pandeiro (Sao<br />

Paulo, 1989), p. 57.<br />

20 J. N. Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary<br />

(London, 1982), pp. 180-1.