BEYOND SHARED LANGUAGE - Society for Contemporary Craft

BEYOND SHARED LANGUAGE - Society for Contemporary Craft

BEYOND SHARED LANGUAGE - Society for Contemporary Craft

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

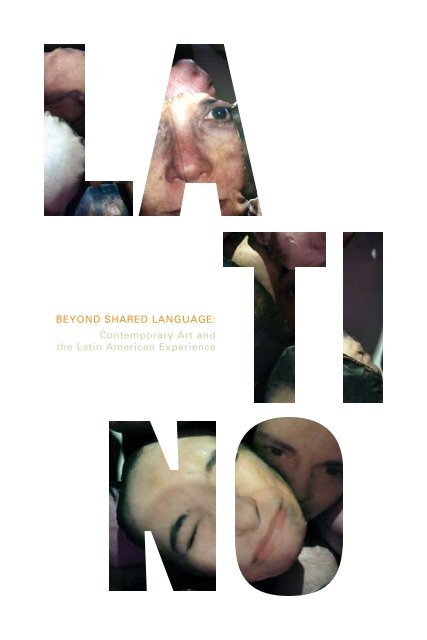

<strong>BEYOND</strong> <strong>SHARED</strong> <strong>LANGUAGE</strong>:<br />

<strong>Contemporary</strong> Art and<br />

the Latin American Experience

SOCIETY FOR<br />

CONTEMPORARY CRAFT<br />

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania<br />

May 1–August 29, 2009

Elia Alba, Portrait “Doll Heads’’<br />

of friends and family by the artist

Beyond Shared Language: <strong>Contemporary</strong> Art and the Latin American Experience is made possible,<br />

in part, by the Pennsylvania Humanities Council and the National Endowment <strong>for</strong> the Humanities;<br />

the Allegneny Regional Asset District; the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts; and the Elizabeth R.<br />

Raphael Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation.

4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

6 ESSAY<br />

14 ALEJANDRO AGUILERA<br />

18 ELIA ALBA<br />

22 PEDRO CRUZ-CASTRO<br />

26 SUSANA ESPINOSA<br />

30 OVIDIO GIBERGA<br />

34 TAMARA KOSTIANOVSKY<br />

38 SILVIA LEVENSON<br />

42 MIGUEL LUCIANO<br />

46 JEANNINE MARCHAND<br />

50 RAQUEL QUIJANO<br />

FELICIANO<br />

54 FRANCO MONDINI-RUIZ<br />

58 COURTNEY SMITH<br />

62 WALKA STUDIO<br />

CLAUDIA BETANCOURT<br />

& RICARDO PULGAR<br />

66 ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES

RECONOCIMIENTOS<br />

Con la exposición Más allá del idioma: El arte contemporáneo y la experiencia latinoamericana<br />

reconocemos el trabajo de artistas latinoamericanos de diversos orígenes y experiencias culturales<br />

y celebramos la diversidad y cosmovisión de esta importante communidad.<br />

Mediante la palabra hablada o escrita, las culturas se esfuerzan diariamente por mantener sus<br />

identidades étnicas y colectivas en el contexto social, cultural, histórico, económico y político.<br />

Como la palabra hablada y escrita, el arte es un idioma visual, una voz utilizada individual y<br />

colectivamente para expresar pensamientos, ideas y necesidades. Mediante las 42 obras en la<br />

exposición, creadas por 14 artistas latinoamericanos (un grupo heterogéneo de individuos<br />

cuyos países de origen, patrones de migración, perfiles socioeconómicos, hábitos del habla y<br />

características físicas varían), la exposición explora asuntos relacionados con la identidad cultural<br />

y étnica, así como la fragilidad y fluidez de su idioma visual. Frente a estas obras el espectador<br />

tiene la oportunidad de conectar con la vida de individuos extraordinarios y comprender mejor<br />

las experiencias de otros grupos culturales.<br />

Quedamos muy agradecidos a los artistas por compartir generosamente su trabajo para realizar<br />

esta exposición. Agradecemos también a las galerías, los coleccionistas privados y especialmente<br />

al curador de El Museo del Barrio en Nueva York, Elvis Fuentes, por proveer un ensayo sobre las<br />

tendencias actuales en el arte contemporáneo latinoamericano.<br />

Debemos gracias también a la Coordinadora de las Exposiciones del SCC, Kati Fishbein, por su<br />

apoyo y dedicación a través de todas las fases del proyecto y por la excelencia en el diseño e<br />

instalación de la muestra; a la Directora de Educación del SCC, Laura Rundell, por desarrollar los<br />

programas de educación relacionados con la exhibición; a Chelsea Fitzgerald por sus habilidades<br />

de traducción; y a Paul Schifino por diseñar este hermoso catálogo.<br />

Reconocemos a nuestros socios de Center <strong>for</strong> Latin American Studies, en University of<br />

Pittsburgh; a Marisol Wandiga y Latin American Cultural Union, por su ayuda y dedicación al<br />

proyecto; asimismo, a las organizaciones Pennsylvania Humanities Council, National Endowment<br />

<strong>for</strong> the Humanities, Allegheny Regional Asset District, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts,<br />

Elizabeth R. Raphael Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation y otros donantes generosos por apoyar<br />

esta exposición.<br />

Kate Lydon<br />

Directora de Exposiciones<br />

4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

With our presentation of Beyond Shared Language: <strong>Contemporary</strong> Art and the Latin American Experience,<br />

we recognize Latin American artists from diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences and celebrate<br />

the diversity and worldviews of this important population.<br />

Through the spoken and the written word, cultures strive to maintain their ethnic, collective identities<br />

in the context of social, cultural, historical, economic, and political dimensions of daily living. Like<br />

spoken and written language, art is a visual language—a voice used individually and collectively to<br />

communicate thoughts, ideas, wants, and needs and to express meaning.Through the 42 works in the<br />

show, created by 14 artists of Latin American descent—a heterogeneous group of individuals whose<br />

countries of origin, migration patterns, socioeconomic profiles, Spanish language dialects, and physical<br />

characteristics differ—the exhibition explores issues relating to cultural identity, ethnicity, and both the<br />

fragility and fluidity of their visual language. In the exploration of these works audiences have the<br />

chance to connect with the lives of unique individuals and better understand the experiences of other<br />

cultural groups.<br />

For so generously sharing their work <strong>for</strong> this exhibition, we are most grateful to the participating<br />

artists, galleries, private collectors and especially Elvis Fuentes, curator at El Museo del Barrio in New<br />

York <strong>for</strong> providing a thought-provoking essay <strong>for</strong> this catalogue that strongly addresses current trends<br />

in contemporary Latin American art.<br />

It is with great appreciation that I thank SCC’s Exhibitions Coordinator, Kati Fishbein <strong>for</strong> her<br />

professionalism and support throughout all phases of the project and <strong>for</strong> her dedication and excellence<br />

in the design and the installation of the exhibition, SCC’s Education Program Manager, Laura Rundell<br />

<strong>for</strong> developing related education programs, Chelsea Fitzgerald <strong>for</strong> her translation skills and<br />

Paul Schifino <strong>for</strong> designing this beautiful catalogue.<br />

We recognize our partners the Center <strong>for</strong> Latin American Studies at the University of Pittsburgh and<br />

Marisol Wandiga and the Latin American Cultural Union <strong>for</strong> their assistance and dedication to the<br />

project; and the Pennsylvania Humanities Council; the National Endowment <strong>for</strong> the Humanities; the<br />

Allegheny Regional Asset District; the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts; the Elizabeth R. Raphael<br />

Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation and other generous donors <strong>for</strong> supporting this exhibition.<br />

Kate Lydon<br />

Director of Exhibitions<br />

5

EL OFICIO DE CONTEMPORANEIZAR<br />

LA ARTESANIA<br />

En 1995, el Salón Nacional de Artes Plásticas de La Habana otorgó el premio de curaduría a un<br />

proyecto titulado ‘‘El oficio del arte’’, de Dannys Montes de Oca. La propuesta se apoyaba en el<br />

hecho de que el arte cubano del momento protagonizaba una ‘‘vuelta al oficio’’, a la producción<br />

de obras cuidadosamente ejecutadas. En otras palabras, constataba el <strong>for</strong>talecimiento de una<br />

tendencia a la producción de objetos bellos, listos para ser comercializados. El contexto estaba<br />

signado por la peor crisis económica y social en Cuba de la que se tenga memoria y la tímida<br />

entrada del mercado de arte, un viejo desconocido para varias generaciones de artistas <strong>for</strong>madas<br />

bajo la égida del socialismo. Este retorno iba a contracorriente de las prácticas conceptuales de<br />

la década anterior (neo-dadaístas o herederas del Fluxus, que rechazaron los estándares prevalecientes<br />

en el arte a través de prácticas culturales antiartísticas), y ahondaba en cierto cinismo<br />

manifiesto en la avidez de los artistas jóvenes por vender su trabajo al mejor postor (apenas dos<br />

años antes, se había realizado la exposición “Cómprame y cuélgame,” en la que participaron<br />

algunos pronto convertidos en estrellas, tales como Kcho y Los Carpinteros). Bajo las nuevas<br />

circunstancias de una economía de mercado (la misma que rige en el resto del mundo), a la cual<br />

no estaban acostumbrados, los artistas jóvenes se vieron <strong>for</strong>zados a convertirse en pequeños<br />

empresarios (“trabajadores por cuenta propia,” según la nomenclatura utilizada por el gobierno).<br />

Era el final de una época, pues hasta entonces las instituciones culturales habían ofrecido<br />

el apoyo necesario. Ahora debían arreglárselas por sí mismos y adiestrarse en la creación de<br />

cosas bellas para generar divisas. El reto era insertar dicha práctica, abiertamente mercantil, en<br />

un discurso que fuera de interés cultural, de manera que las instituciones pudieran promoverlos<br />

sin rubor.<br />

Las respuestas a dicho reto oscilaron desde la conceptualización del ’’rescate’’ de los oficios<br />

artesanales en términos del debate estético postmoderno entre lo cocido y lo crudo -que favorece<br />

la imagen sobre lo narrativo, y lo figurado sobre lo discursivo-, arte culto y arte popular; hasta la<br />

apropiación de los valores histórico-culturales asociados a dichos oficios, que podían ser<br />

aprovechados en función de la crítica social, política o incluso ideológica. Por ejemplo, Los<br />

Carpinteros recuperaron la ebanistería, que combinaron con pintura en esculturas de notas<br />

autobiográficas; fue un ejercicio cínico que culminó en su tesis de grado con la simulación de una<br />

subasta en la que todas sus obras eran vendidas. En cambio, Kcho utilizó el reciclaje de materiales<br />

y la fibra para realizar esculturas en las que imbricaba los símbolos de lo sagrado (religiones<br />

afrocubanas) y lo nacional (la isla, la bandera y la estrella). El subtexto era que las prácticas<br />

religiosas populares habían sido tildadas por el propio Castro como superstición y rezagos del<br />

capitalismo que debían ser eliminados. Otros artistas integraron oficios como la yesería, la<br />

cerámica, el tejido y el bordado, en muchos casos aludiendo a su marginalidad dentro del modelo<br />

económico socialista.<br />

6

Cuando Kate Lydon me visitó en El Museo del Barrio hace varios meses, buscando in<strong>for</strong>mación<br />

sobre artistas latinoamericanos que utilizaban la artesanía en su trabajo, me percaté de cuán<br />

diferente era la mirada que cada uno tenía sobre el tema. Mientras ella se enfocaba en los<br />

materiales utilizados (fibra, barro, vidrio, textiles, cuero, papel), es decir, en la dimensión estética<br />

del fenómeno, yo buscaba las resonancias culturales y sociales que dichos usos tenían en el<br />

discurso poético de cada artista, probablemente influido por la experiencia cubana de 1995.<br />

Alejandro Aguilera es un artista que emergió en la década de 1980 en Cuba. Con un acercamiento<br />

neo-dadaísta, armaba esculturas de lenguaje figurativo con materiales precarios, tales como<br />

madera vieja, latón y alambre. En una ocasión, representó héroes latinoamericanos (José Martí,<br />

Simón Bolívar, Ché Guevara) junto a Jesucristo, semejando esculturas religiosas con halos. Este<br />

trabajo encuentra eco en términos de morfología y lenguaje en el retrato doble mostrado aquí.<br />

Las figuras representadas son María Izquierdo, artista que desarrolló su trabajo a la sombra de<br />

Frida Kahlo, y Ana Albertina Delgado, pintora contemporánea de Aguilera, que ha padecido<br />

semejante situación. Aguilera utiliza el sentido constructivo que le es característico para denotar<br />

la <strong>for</strong>taleza de estos personajes femeninos a los que claramente admira. Otras dos artistas<br />

se apoyan en la construcción y el ensamblado: Courtney Smith y Raquel Quijano, aunque los<br />

materiales y las fuentes iconográficas son distintas. Al igual que Aguilera, Smith ha venido<br />

trabajando con trozos desechados de mobiliarios de madera desde el comienzo de su carrera. Sin<br />

embargo, pone énfasis en cierto tipo de muebles, correspondientes a la modernidad brasilera y<br />

en diálogo con ella, que en su momento constituyeron objetos de lujo, lo cual otorga cierto<br />

sentido nostálgico a sus piezas. Lo más intrigante es la apariencia orgánica que logra hasta en<br />

las configuraciones abstractas; esto se debe a las articulaciones de un sabio diseño, que tiene<br />

una interlocutora ideal en las cajas de papel de Quijano. Fruto y receptora de una larga tradición<br />

de trabajo con el papel y de grabado en Puerto Rico, Quijano es considerada una de las artistas<br />

en activo más inquietas y renovadoras. En la serie de Andamios aborda el tema del perenne<br />

desarrollismo puertorriqueño, con sus expansiones de asfalto indiscriminadas, que ponen en<br />

jaque los ecosistemas tanto naturales como sociales. Anteriormente, la artista había creado<br />

un libro pop-up ilustrando los poemas de Luis Palés Matos con escenas de una ciudad que<br />

con<strong>for</strong>maban un paisaje de edificios. Los andamios llevan estas búsquedas un paso más<br />

adelante, al terreno escultórico, sin perder la delicadeza y sofisticación de sus entramados.<br />

Barroco en la acumulación y en el diálogo interobjetual es Franco Mondini-Ruiz. Otrora abogado,<br />

este artista de Texas critica con refinado humor (y servido en la mejor vajilla) los estereotipos<br />

creados alrededor de la figura del inmigrante mexicano y su entorno en el sur de los Estados<br />

Unidos. En La bebé ‘mojada,’ una figurilla blanca como azúcar se sumerge en una taza de té,<br />

7

decorada con una escena pastoral y bordeada por una cinta de oro. Sobre el platillo, también<br />

profusamente adornado, hay dos suculentas galletas y una cucharita. Mondini-Ruiz parece<br />

invitarnos a revolver el té y diluir la figurilla como desaparece el mojado en la estructura<br />

económica norteamericana.<br />

El dúo Walka Studios, <strong>for</strong>mado por Claudia Betancourt y Ricardo Pulgar, es probablemente el que<br />

más se acerca a la artesanía como tal: se dedican a la orfebrería, tradición que les llega por herencia<br />

familiar. Walka Studio aprovecha el valor poético de los pequeños gestos que alteran la función<br />

de los objetos para tratar temas de índole social. En Los pájaros cantan en pajarístico pero los<br />

escuchamos en español!¡Chile, sal de la jaula!, toman un canario de plástico adquirido en un<br />

mercado popular y le integran elementos de valor (oro, lapislázuli, bronce) que son también<br />

contraproducentes: el canario queda atrapado en una jaula. El hecho refuerza la precariedad del<br />

símbolo nacionalista (el canario representa a Chile).<br />

Lo mismo podría decirse del trabajo del Nuyorican Miguel Luciano. En Plátano platinado<br />

(Platinum Plantain), utiliza la técnica del fundido, en este caso de platino, para cubrir un plátano,<br />

con el que se identifica a muchos latinos en los Estados Unidos. El título propone un juego de<br />

palabras, aprovechando la similitud fonética de los vocablos. De este modo, la belleza del metal<br />

precioso contrasta con el carácter orgánico y, por lo tanto, perecedero de la fruta. Luciano cita<br />

obras paradigmáticas, desde El pan nuestro (1905), de Ramón Frade, hasta La transculturación<br />

del puertorriqueño (1975), de Carlos Irizarry. Asimismo, alude a la cultura pop y su exaltación de<br />

supuestos orgullos latinos, que explotan más que combaten la marginalidad. Su obra anterior<br />

en pintura e instalación, ha explorado también estas imbricaciones, en particular relacionadas<br />

con la identidad cultural nuyorican. Sin ser demasiado moralizante, para Luciano el lujo de un<br />

bling-bling (y el orgullo asociado a él) esconde un interior en putrefacción.<br />

La identidad ocupa un lugar esencial en otras dos artistas, las cuales coincidentemente trabajan<br />

con la tela. Elia Alba ha hecho de la confección de máscaras la piedra angular de su obra.<br />

Descendiente de emigrados dominicanos, una comunidad que comienza a definir una voz propia<br />

en las artes visuales con artistas como Freddy Rodríguez, Scherezade y Nicolás Dumit, Alba ha<br />

encarado el tema del mestizaje y la indeterminación racial en piezas como La jabá, una especie<br />

de parodia del Banana Dance, de Josephine Baker. Los bananos en la falda de la bailarina (en<br />

realidad un travesti encarnado por Dumit) son sustituidos por rostros de dominicanos, a quienes<br />

se les apoda ‘‘bananos". Desde aquí, las máscaras han recorrido un camino que les ha permitido<br />

rebasar el "deja vu’’ de cierto arte digital de Photoshop. En ocasiones, las <strong>for</strong>mas adquieren tonos<br />

más viscerales como la serie de vestuarios en los que reproduce los órganos sexuales femeninos<br />

en tres variantes: blanca, negra y mestiza.<br />

8

Por su parte, Tamara Kostianovsky encarna otra perspectiva sobre el tema, situándose en el cruce<br />

entre las identidades nacional y personal de la artista. La carne hace referencia a la principal<br />

industria argentina. Pero su propia ropa, de la cual se sirve para construir las esculturas blandas,<br />

aporta otras capas de significados. Kostianovsky narra que su determinación de utilizar su ropa<br />

fue <strong>for</strong>tuita al principio, cuando en 2000, a raíz la crisis monetaria de su país, su cuenta bancaria<br />

fue congelada y se vio en la obligación de hacer arte con lo que tenía a la mano; pero más tarde,<br />

se convirtió en una decisión política. Literalmente, Kostianovsky personaliza el conflicto contra<br />

la violencia implícita en el sacrificio animal, canibalizando su propia ropa. La fibra del tejido<br />

recuerda casi con cruel fidelidad la fibra de la carne. Por su parte, el venezolano Pedro Cruz<br />

Castro intenta metafóricamente devolver los materiales curados y preparados por el hombre a su<br />

estado natural cuando dibuja sobre cueros las figuras—de todos modos incompletas—de<br />

animales domesticados (explotados) por el hombre (cerdo, cabra, caballo). Antes lo hizo con la<br />

madera, integrando árboles a muebles antiguos.<br />

Silvia Levenson ‘‘borda’’ hebras de vidrio fundido sobre fotografías de su niñez. El tema de sus<br />

trabajos es la memoria, presentada aquí con claridad gráfica, así como con un trasfondo político<br />

asociado con los desaparecidos durante la dictadura de Videla en la Argentina de 1976. También<br />

Susana Espinosa alude al universo infantil, pero en un lenguaje tradicionalista y con aliento<br />

decorativo. De origen argentino, pero radicada por décadas en Puerto Rico, Espinosa ayudó a<br />

fundar un movimiento de cerámica artística en la isla, que tiene entre sus recientes frutos a<br />

Jeannine Marchand. Esta alude a la sensualidad como asunto, siendo el acabado de las piezas el<br />

mejor testimonio de su (im)potencia en el contexto de un museo: la textura invita al roce, pero la<br />

institución suprimirá el placer de tocarlas. Las vasijas de Ovidio Giberga, imitaciones de la cerámica<br />

precolombina de Moche, contrastan con las obras de Marchand. Se sitúan en el borde entre<br />

lo grotesco y lo nostálgico sin llegar a ser alguno por completo. La cerámica parecería<br />

ofrecer menos oportunidades para los creadores contemporáneos latinoamericanos. Pero no hay<br />

dudas de que completan un panorama visual donde la artesanía se presenta como un ejercicio<br />

divertido y pluri-significativo.<br />

Elvis Fuentes, Curador de El Museo del Barrio, Nueva York desde 2006, se graduó de la Universidad de la Habana (Historia<br />

del arte, 1999), y trabajó como curador en la Fundación Ludwig de Cuba (1999-2002) y el Instituto de Cultura<br />

Puertorriqueña (2004-2006). Su proyecto El grabado como metá<strong>for</strong>a ganó el Grand Prix de la Bienal Internacional de Artes<br />

Gráficas de Ljubljana (2005). Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Impresiones tempranas (Trienal Poli/Gráfica de San Juan, 2004) ha<br />

sido reconocida como una contribución notable al estudio de la obra de este artista. Sus proyectos más recientes incluyen<br />

El Museo’s 5th Bienal: The [S] Files 007, Matando el tiempo (Exit Art, 2007), y Rewind… Rewind… Tres décadas de video<br />

arte en Puerto Rico (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 2005-2006). Director artístico fundador de la primera feria de arte<br />

en el Caribe, CIRCA Puerto Rico 2006, Fuentes publica regularmente ensayos en revistas y catálogos de arte. En estos<br />

momentos se encuentra preparando la primera instalación de la Colección permanente de El Museo del Barrio.<br />

9

THE ART OF CONTEMPORIZING CRAFT<br />

In 1995, the Salon de Arte Cubano Contemporáneo (organized by the National Council of Visual Arts)<br />

of Havana, Cuba granted the Prize of Curatorship to Dannys Montes de Oca <strong>for</strong> a project titled<br />

“El oficio del arte” (The <strong>Craft</strong> of Art). The proposal was supported by a trend in Cuban art, which<br />

recognized a “revival of craftsmanship,” with the focus on the production of carefully executed work.<br />

This trend saw an increase in the creation of beautiful objects, ready to be commercialized. The<br />

climate in Cuba at that time, while marked by its worst financial and social crisis of the century, saw<br />

the emergence of a new art market unique to generations of artists trained under the aegis of socialism.<br />

This arts revival, countercurrent to conceptual practices that had predominated in the previous<br />

decade—neo-Dadaist and neo-Fluxus artists who rejected the prevailing standards in anti-art cultural<br />

works—deepened a certain cynicism among avid, young artists who sought to sell their work to the<br />

highest bidder. (Hardly two years earlier, the exhibition “Cómprame y cuélgame” [Buy Me and Hang<br />

Me] had been realized, in which some who participated soon turned into stars, such as Kcho and Los<br />

Carpinteros—the Carpenters). Under this new market—the same economy that ruled in the rest of<br />

the world—young artists were <strong>for</strong>ced to become small entrepreneurs,“independent workers” according<br />

to the nomenclature used by the government. Having witnessed the end of an era, cultural institutions<br />

no longer offered necessary support; artists now had to manage on their own and develop skills enabling<br />

them to make beautified things to generate currency. The challenge was to integrate this practice, openly<br />

mercantile, in a discourse of cultural interest, so that the institutions could promote them.<br />

The artists’ response to this challenge varied from the metaphorical rescue of the crafts in terms of the<br />

postmodern aesthetic debate between “what’s cooked and what’s raw,” which favored the image over<br />

the narrative and the figural over the discursive (in other words, between cultured art and folk art);<br />

to the appropriation of historical-cultural values associated with these occupations, that could be<br />

advantageous towards social critic, politics or even ideology. For example, Los Carpinteros reintroduced<br />

woodworking combined with painting in autobiographical sculptures; a cynical exercise that culminated<br />

in their thesis, which was the simulation of an auction in which all works were sold. In contrast, Kcho<br />

used recycled materials and fiber to create sculptures with overlapping symbols of the Sacred (Afro-<br />

Cuban religions) and the Nation (the island, the flag and the star). The subtext was that popular<br />

religious practices had been labeled by Castro as superstition, and remnants of Capitalism that had to<br />

be eliminated. Other artists integrated crafts like plaster casting, ceramics, sewing and embroidering, in<br />

many cases alluding to their marginality within the economic socialist model.<br />

When Kate Lydon visited me at El Museo del Barrio several months ago, looking <strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation on<br />

Latin American artists who used craft in their work, I noticed how different our views were on the<br />

subject.While she focused on the materials used (fiber, clay, glass, textiles, leather, paper), that is to say,<br />

in the aesthetic dimension of the phenomenon, I looked <strong>for</strong> the cultural and social resonances that<br />

these materials had within the poetic content of each artist, probably influenced by the Cuban<br />

experience of 1995.<br />

10

Alejandro Aguilera is an artist who emerged during the 1980s.With a neo-Dadaist approach, he built<br />

figurative sculptures with precarious materials, such as old wood, tin and wire. Once, he represented<br />

Latin American heroes (José Martí, Simon Bolivar, Ché Guevara) next to Jesus Christ, resembling<br />

religious sculptures with halos.This work receives response in terms of morphology and language in<br />

the works shown here.The represented figures are María Izquierdo, an artist who developed her work<br />

overshadowed by Frida Kahlo, and Ana Albertina Delgado, a painter contemporaneous of Aguilera,<br />

who suffered a similar situation—they both have been overlooked by art historians. Aguilera used his<br />

constructive sense to denote the strength of these feminine characters, which he clearly admires.<br />

Although the materials and the iconographic sources are different, two other artists inclined towards<br />

construction and assemblage are Courtney Smith and Raquel Quijano. Like Aguilera, Smith has been<br />

working with discarded pieces of wood since the beginning of her career.Yet, she focuses on certain<br />

types of furniture, mostly in the style of Brazilian modernity and responding to it, once constituted<br />

as luxury objects, now grants certain nostalgic sense to her pieces. Most intriguing is the organic<br />

appearance she achieves in her abstract configurations; this is due to the brilliant joint design, which<br />

has an ideal interlocutor in Quijano’s paper cubes. As a product and recipient of a long tradition of<br />

works on paper and engraving in Puerto Rico, Quijano is considered one of the more restless and<br />

renovating artists. In the Scaffolds Series she approaches the subject of the perennial Puerto Rican<br />

development policy, with its indiscriminate asphalt expansions, that set the ecosystems in check, natural<br />

as well as social. Previously, the artist had created a pop-up book illustrating the poems of Luis Palés<br />

Matos with scenes of a city that <strong>for</strong>med a landscape of buildings.The Scaffolds go beyond this, to the<br />

sculptural terrain, without losing the delicacy and sophistication of their lattices.<br />

Baroque in his accumulation and dialogue with objects is Franco Mondini-Ruiz. Once a lawyer, this<br />

Texan artist criticizes with refined humor (and served on the best china) the stereotypes created around<br />

the Mexican immigrant and their surroundings in the south of the United States. In Baby Mojada,<br />

Mondini-Ruiz has taken a figurine, white as sugar, submerged it in a teacup, and decorated it with a<br />

pastoral scene bordered by a gold band. On the saucer, also profusely adorned, there are two succulent<br />

cookies and a teaspoon. Mondini-Ruiz seems to invite us to stir the tea and dilute the figurine just<br />

like the mojado in the North American economic structure disappears.<br />

The duo at Walka Studio, Claudia Betancourt and Ricardo Pulgar, are probably the closest ones to<br />

craft: they are dedicated to jewelry, an inherited family tradition.Walka Studio takes advantage of the<br />

poetic value of small gestures that alter the function of the objects to deal with subjects of social nature.<br />

In Los pájaros cantan en pajarístico pero los escuchamos en español Chile: Get Out of the Cage! they used a<br />

ready-made plastic canary and integrated precious elements (gold, lapis lazuli, bronze), which are<br />

also counter-productive: the canary is trapped in a cage. This rein<strong>for</strong>ces the precariousness of the<br />

nationalistic symbol (the canary represents Chile).<br />

11

The same could be said of the work of Nuyorican Miguel Luciano. In Pure Plantainum, he used<br />

casting techniques, in this case platinum, to cover a plantain, with which many Latinos in the United<br />

States are identified.The title proposes a word game, taking advantage of the phonetic similarity of the<br />

words. In this way, the beauty of the precious metal contrasts with the organic character and, there<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

the perishable nature of the fruit. Luciano mentions paradigmatic Puerto Rican artworks, from El pan<br />

nuestro (1905) by Ramón Frade to La transculturación del puertorriqueño (1975), by Carlos Irizarry and<br />

alludes to pop-culture and its glorification of assumed Latin pride, which exploit even more than they<br />

combat marginality. His previous works in painting and installation, also explored this overlapping, in<br />

particular relating to the Nuyorican cultural identity, a blending of the terms ‘‘New York’’ and ‘‘Puerto<br />

Rican,’’ referring to the members of Diaspora located in or around New York.Without being too moralizing,<br />

<strong>for</strong> Luciano the luxury of a bling-bling (and the pride associated to it) hides a putrid interior.<br />

Identity occupies an essential position in the sculpture of two other artists, who coincidently work with<br />

fabric. Elia Alba has made the fabrication of masks the corner stone of her work. Descended from<br />

Dominican Republic emigrants, and a community who began to define its own voice in the visual arts<br />

with artists like Freddy Rodríguez, Scherezade and Nicolás Dumit Estévez, Alba has undertaken the<br />

subject of miscegenation and racial indetermination in pieces like La jabá, a kind of parody of the<br />

famous, early 20th century Banana Dance by Josephine Baker. The bananas on the dancer’s skirt (in<br />

fact a transvestite incarnated by Dumit) are replaced by Dominican faces, which are called “bananos.”<br />

From here, the masks have crossed a path that has allowed them to surpass the “deja vu” of certain<br />

Photoshop digital art. Occasionally in Alba’s work, the <strong>for</strong>ms possess a more visceral tone like the series<br />

of costumes in which she reproduces the feminine sexual organs in three variants: white, black and mulatto.<br />

Conversely,Tamara Kostianovsky incarnates another perspective on the subject, placing herself in the<br />

crossing between her national and personal identities. Her depiction of animal flesh makes reference to<br />

the main Argentinean industry. But her own clothes, which she uses to construct the soft sculptures,<br />

contribute other layers of meaning. Kostianovsky narrates that her determination to use her clothes<br />

was <strong>for</strong>tuitous at the beginning of her career, when in 2000, because of the economic crisis in her<br />

country, her bank account was frozen and she was <strong>for</strong>ced to make art with what she had at hand; but<br />

later, it became a political decision. Literally, Kostianovsky personalizes the conflict against implicit<br />

violence in animal sacrifice, cannibalizing her own clothes.The fiber of the weave remembers almost<br />

with cruel fidelity the fiber of the flesh. Likewise, the Venezuelan Pedro Cruz-Castro metaphorically<br />

attempts to return the cured and processed materials to their natural state as he draws figures on<br />

hides—of incomplete—domesticated (exploited) animals (pig, goat, horse). Previously, he worked<br />

with wood, integrating trees into antique furniture.<br />

12

Silvia Levenson ‘‘embroiders’’ fused glass fibers onto photographs of her childhood.The focus of her<br />

work is memory, displayed here with graphic clarity, with an associated political background with the<br />

disappeared ones during the dictatorship of Videla in the Argentina of 1976. Also Susana Espinosa<br />

alludes to the infantile universe, but in a traditionalistic language and with decorative breath.<br />

Of Argentine origin, but having resided in Puerto Rico <strong>for</strong> decades, Espinosa helped establish a<br />

movement of artistic ceramics on the island, which among its recent fruits is Jeannine Marchand.<br />

Marchand alludes to sensuality as a subject, the surface treatment of the pieces serve as the best testimony<br />

of its (im)potence in the context of a museum experience: the texture invites to caress, but the institution<br />

will suppress the pleasure to touch them. Ovidio Giberga’s vessels, imitations of the pre-Columbian<br />

ceramics of Moche, contrast with Marchand’s works. They border between the grotesque and the<br />

nostalgic without completely being either one. Ceramics would seem to offer fewer opportunities <strong>for</strong><br />

the Latin American contemporary creators, but there is no doubt that they complete a visual scene<br />

where craft appears as an enjoyable and multi-layered practice.<br />

Elvis Fuentes, Curator of El Museo del Barrio, New York since 2006, graduated from Havana University (Art History, 1999),<br />

and served as Curator at the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba (1999-2002), and the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture (2004-<br />

2006). His project Print As Metaphor won the Grand Prize at the Ljubljana International Biennial of Graphic Arts (2005).<br />

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Early Impressions (San Juan Poly/Graphic Triennial, 2004) has been regarded as a major contribution to<br />

the study of this artist’s oeuvre. His most recent projects include El Museo's 5th Biennial, The [S] Files 007, Killing Time (Exit<br />

Art, 2007), and Rewind… Rewind… Three Decades of Video Art in Puerto Rico (Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, 2005-2006).<br />

Founding Artistic Director of the first art fair of the Caribbean, CIRCA Puerto Rico 2006, Fuentes publishes essays in art<br />

magazines and catalogs regularly. Currently, he is curating the first installment of the Permanent Collection of El Museo<br />

del Barrio.<br />

13

ALEJANDRO AGUILERA<br />

Attraction, 2007<br />

Polychromed wood, Georgia clay, metal, paper, graphite<br />

88 x 30 x 27 inches<br />

Courtesy of Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, Miami, FL<br />

Estos trabajos mezclan la historia y la historia del arte, la naturaleza y la cultura. En este<br />

espacio, las ideas del mundo de ideología coexisten con las imágenes y los estilos artísticos que<br />

surgen de la estética.<br />

Ana y María es un retrato de Ana Albertina Delgado, una artista cubana que creó algunor de los<br />

trabajos más personales y artísticos de nuestra época y Mariá Izquierdo, una artista mexicana<br />

que utilizó elementos ingenuos en sus pinturas, y creyó totalmente en México como una fuente<br />

rica y diversa de inspiración. Las figuras en este retrato, hecho de vainilla, canela, raíz amarilla,<br />

anís y mejorana — con posturas crudas y con miradas estoicas — recuerdan Las Dos Fridas, un<br />

doble autorretrato pintado en 1939 por Frida Kahlo, una contemporánea de Izquierdo.<br />

These works blend history and art history, nature and culture. In this space, ideas from the world of<br />

ideology co-exist with images and artistic styles arising from aesthetics.<br />

Ana and María is a portrait of Ana Albertina Delgado, a Cuban artist who created some of the most<br />

personal and artistic works of our time, and Mariá Izquierdo, a Mexican artist who utilized naïve<br />

elements in her paintings, and believed strongly in Mexico as a rich and diverse source of inspiration.<br />

The figures in this portrait, made of vanilla, cinnamon, yellow root, anise and marjoram — with their<br />

crude poses, and stoic gazes — are reminiscent of The Two Fridas; a double self-portrait painted in 1939<br />

by Frida Kahlo, a contemporary of Delgado and Izquierdo.<br />

14

Nefertiti, the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin Collection,<br />

the Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

Ana and Maria, 2007<br />

Polychromed wood, metal, graphite, corn,<br />

vanilla, beans, anise, yellow root<br />

Installation<br />

Courtesy of Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, Miami, FL<br />

17

ELIA ALBA<br />

Masks, 2004<br />

Photocopy transfer on muslin, thread<br />

Installation, 10 life-size masks<br />

Esta obra examina aspectos del retratismo, la representación y el mestizaje (la mezcla literal<br />

e imaginada de razas), el per<strong>for</strong>mance y el lugar de la figura humana dentro de nuestra red de<br />

normas sociales. Inspirada por el trabajo de su madre en la industria del vestir, Elia Alba llegó a<br />

combinar la costura con la fotografía y borro-difuminó enturbió las fronteras entre el retratismo<br />

y la naturaleza muerta en su obra. Sus cabezas son como marcadores de la cultura y la historia,<br />

metá<strong>for</strong>as de la condición humana y los signos de identidad. Muchas de sus obras llegan a<br />

ser instrumentos utilizados en la presentación y para hacer preguntas fundamentales. ¿Qué<br />

es el significado de raza o género? ¿Cómo se marcan los cuerpos, las caras y las personas por<br />

estos conceptos?<br />

18

This body of work examines aspects of portraiture, representation and miscegenation (literal and imagined<br />

mixing of races), per<strong>for</strong>mance and the place of the human figure within our web of social norms.<br />

Inspired by her mother’s work in the garment industry, Elia Alba came to combine sewing with<br />

photography, blurring the boundaries between portraiture and still life in her work. Her heads are seen<br />

as markers of culture and history, metaphors <strong>for</strong> the human condition. Many of her works become tools<br />

used in per<strong>for</strong>mance and ask fundamental questions.What is the significance of race or gender? How<br />

are bodies, faces and people marked by these concepts?<br />

19

If I Were A..., 2003<br />

Photocopy transfer on muslin, thread,<br />

created by digitally manipulating the<br />

color of the artist’s skin and body parts<br />

Life size<br />

Collection of El Museo del Barrio, New York, NY<br />

Acquired through ‘‘PROARTISTA: Sustaining the<br />

Work of Living <strong>Contemporary</strong> Artists,’’ a fund<br />

from the Jacques and Natashia Gelman Trust,<br />

and a donation from the artist.<br />

20

Portrait “Doll Heads’’ of friends and family by the artist<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

21

PEDRO CRUZ-CASTRO<br />

Mi trabajo se basa en explorar materiales, el proceso revela el contenido. También estoy<br />

fascinado por la relación entre el mundo natural y el hecho por el hombre. El trabajo reciente ha<br />

empujado las fronteras entre estas relaciones a límites absurdos y humorísticos. El puerco, La<br />

cabra y El caballo <strong>for</strong>man parte de una serie de dibujos quemados en cuero. El cuero<br />

animal es el origen del concepto y el soporte para el dibujo; las secciones sugieren el trabajo<br />

de un carnicero.<br />

My work is about exploring materials, the process reveals the content. I am also fascinated by the<br />

relationship between the natural and man-made worlds. Recent work has pushed the boundaries<br />

of these relationships to absurd and humorous limits. Pig, Goat and Horse are part of a series of<br />

drawings burnt on leather: the animal hide is the source of the concept and the support <strong>for</strong> the<br />

drawing; the sections suggest a butcher’s work.<br />

22

Goat, 2007<br />

Leather<br />

60 x 52 inches<br />

23

Pig, 2007<br />

Leather<br />

31 x 42 inches<br />

24

Untitled, 2004, mixed media on wood<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

25

SUSANA ESPINOSA<br />

Viaje por tierra y mar es una serie de vasijas,<strong>for</strong>mas huecas y selladas que han sido alejadas<br />

de su rol utilitario. Estas vasijas, de <strong>for</strong>mas sencillas, fueron construidas con planchas de barro.<br />

La simpleza de la superficie permitió desarrollar imágenes profundas pero plácidas. Esta<br />

cohabitación de sentidos <strong>for</strong>ma parte de mi trabajo.<br />

Desde su niñez, y como un pasatiempo, mi hija ha hecho barquitos de papel. Ella los hace de<br />

cualquier pedazo de papel que encuentre, blancos, ya dibujados, con texturas o de color, con<br />

gesto rápido. Me gusta observar el gesto simple y honesto, como la huella de la mano en objetos<br />

vernáculos o en la obra del artista consumado.<br />

Esos barcos de papel, preciosos y modestos, expresan la esencia que desearía agregar a mi<br />

trabajo, grande o pequeño.<br />

Viaje por tierra y mar is a series of vessels; hollow, sealed <strong>for</strong>ms that have been stripped of their utilitarian<br />

role.These vessels of simple shape are constructed with clay slabs.The simplicity of the surfaces allowed<br />

<strong>for</strong> the development of profound but placid images.This cohabitation of senses is part of my work.<br />

Since childhood, as a past time, my daughter has made small paper boats out of scrap paper she finds<br />

— textured paper, simple white or already drawn paper — as a quick gesture. I like to observe simple<br />

and honest gestures, such as the trace of the hand on vernacular objects or in the work of the<br />

consummate artist.<br />

These beautiful and modest paper boats express the essence that I would like to capture <strong>for</strong> my own<br />

work, be it large or small.<br />

Viaje por tierra y mar, (series) 2008<br />

Ceramic<br />

18 x12 x 4 inches<br />

Courtesy of Galeria Gandia, San Juan, PR<br />

26

Paper boats made by the artist’s daughter<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

Viaje por tierra y mar, (series) 2009<br />

Ceramic<br />

24 x7x 6 inches<br />

Courtesy of Galeria Gandia, San Juan, PR<br />

29

OVIDIO GIBERGA<br />

Seated Male with Organic Binding, 2004<br />

Ceramic<br />

21 x 16 x13 inches<br />

Mi conjunto reciente de trabajos es inspirado por las vasijas rituales de asas estribo de la cultura<br />

Mochica de Perú. La cultura Mochica (los siglos 1-9 DC) creó vasijas rituales con imágenes que<br />

representaron aspectos de su vida cotidiana. Lo que me llamó la attención al principio fue el<br />

diseño y la composición jugetona de las vasijas, pero después de estudiarlós por un tiempo me<br />

quedé intrigado de lo que los trabajos revelaron acerca de las personas, la cultura y la época en<br />

las que fueron creados. Sin un idioma escrito, mucho de lo que es conocido de la cultura Mochica<br />

se ha inferido de los cientos de sus trabajos.<br />

A menudo mis trabajos concluyen con un asa estribo y pico del estilo nostálgico de las cerámicas<br />

Mochica. Las variaciones de la asa y pico sirven como una característica compulsiva de diseño<br />

que cargan las figuras pero lo más importante es que aluden a la noción de una vasija, invitando<br />

al espectador a considerar su propósito y el contenido. La obra llamada La vasija de pie con<br />

mano y pinzas que tiran hilo tiene encima del pico la imagen de una mano agarrando las pinzas<br />

que extraen un hilo de la planta del pie. El hilo representa una continuidad cultural que es difícil<br />

de sostener a causa de su longitud y punto de origen.<br />

My recent body of work draws inspiration from the ancient Moche ritual stirrup vessels of Peru.<br />

The Moche culture (1st-9th Century AD), created ritual vessels with imagery that depicted aspects of<br />

their daily life. I was first impressed by the playful design and composition of the vessels, but then upon<br />

studying them further I became intrigued by what the works revealed about the people,<br />

culture and time in which they were created.With no written language, much of what is known about<br />

the Moche has been inferred from the many hundreds of their works.<br />

My works often conclude with a stirrup spout reminiscent of Moche ceramics.The spout variations<br />

serve as a compelling design feature that burden the figures but more importantly, allude to the notion<br />

of a vessel, and invite the viewer to consider their purpose and contents. The piece titled<br />

Foot Vessel with Hand and Tweezers Pulling Thread has an image at the top of the spout, of a hand holding<br />

tweezers extracting thread that emerges from the sole of the foot.The thread represents a cultural<br />

continuity that is difficult to sustain because of its length and point of origin.<br />

30

Foot Vessel with Hand and Tweezers Pulling Thread, 2006<br />

Ceramic<br />

12 x 15 x 7 inches<br />

32

Sketchbook drawing<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

33

TAMARA KOSTIANOVSKY<br />

Bound, 2007<br />

Curtains and articles of clothing belonging<br />

to the artist, steel, meat hooks and chains<br />

61 x 39 x15 inches<br />

Courtesy of Black & White Gallery/Chelsea, New York, NY<br />

Para la creación de estas obras, usé mi ropa. Utilicé varios tejidos y texturas para conjurar carne,<br />

hueso, cartílago y trozos de grasa en esculturas de tamaño natural de reses muertas. El material<br />

elegido establece conexiones entre lo humano y lo animal, acercando la violencia a un mundo<br />

familiar. Mi intención es confrontar al espectador con la naturaleza grotesca de la violencia y<br />

ofrecer un contexto para reflexionar sobre la vulnerabilidad de nuestra existencia física, la<br />

brutalidad, la pobreza, el consumo y las necesidades voraces del cuerpo.<br />

For the creation of these works I cannibalized my clothes: I used various fabrics and textures to<br />

conjure flesh, bone, gristle and slabs of fat in life-size sculptures of livestock carcasses. The wearable<br />

material draws connections between the physical <strong>for</strong>m of human and animal, bringing violent acts into<br />

a familiar realm. My intention is to confront the viewer with the real and grotesque nature of violence,<br />

and offer a context <strong>for</strong> reflecting on the vulnerability of our physical existence, brutality, poverty,<br />

consumption and the voracious needs of the body.<br />

34

Malice, 2008<br />

Articles of clothing belonging to the artist,<br />

fabric, polyester batting, utility cart<br />

34 x72 x45 inches<br />

Courtesy of Black & White Gallery/Chelsea, New York, NY<br />

36

Slaughter house<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

37

SILVIA LEVENSON<br />

Bibi (Album di famiglia), 2008<br />

Fused glass, acrylic and photo on aluminum<br />

19 3/4 x 13 3/4 x 3/4 inches<br />

Courtesy of Bullseye Gallery, Portland, OR<br />

Con la serie Album Di Famiglia, reflexiono sobre mi niñez. Cuando modifico mis fotos<br />

familiares en realidad trato de curar mi memoria. Mis abuelos, como la mayoría de los<br />

argentinos, vinieron de Europa. Emigraron a Argentina buscando una vida mejor, pero sus hijos<br />

y nietos terminaron volviendo a Europa durante la dictadura en un viaje circular.<br />

Las fotografías están modificadas, ampliadase impresas en el aluminio, a las cuales luego les<br />

aplico vidrio fundido. En estas fotos mi hermana Bibi y yo estamos alimentando palomas en la<br />

Plaza de Mayo. En la misma plaza algunos años después, fuimos buscando nuestros parientes y<br />

amigos que habían desaparecido durante la dictadura de Videla en 1976. Quizás lo que es más<br />

central es la manera en la que la relación fuerte que tenía con mi hermana fue modificada<br />

durante mi exilio en Italia, dejando un vacío que sólo podría ser descrito con la creación de estas<br />

obras de arte.<br />

With my Album di famiglia series I am reflecting on my childhood and trying to heal my own memories<br />

by modifying family photos. My grandparents, like most Argentineans, came from Europe. As they<br />

immigrated to Argentina looking <strong>for</strong> a better life, their children and grandchildren then emigrated to<br />

Europe during the dictatorship in a circular journey.<br />

The photographs are modified, enlarged and printed on aluminium, then I apply fused glass over<br />

the images. In these photos my sister Bibi and I are at Plaza de Mayo feeding pigeons. In the same<br />

square some years later we went looking <strong>for</strong> our missing relatives and friends that had disappeared<br />

during the dictatorship of Videla in 1976. Maybe what is more central is the way in which the strong<br />

relationship I had with my sister was shattered during my immigration to Italy, leaving a void that can<br />

only be described with the creation of these works of art.<br />

38

Tutte al mare (Album di famiglia), 2008<br />

Fused glass, acrylic and photo on aluminum<br />

14 x 19 x 3/4 inches<br />

Courtesy of Bullseye Gallery, Portland, OR<br />

40

Sketchbook drawing<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

41

MIGUEL LUCIANO<br />

Pure Plantainum at King of Platinum, 125th Street<br />

Chromographic print<br />

24 x 18 inches<br />

Mi arte se trata de los intercambios amistosos y dolorosos entre Puerto Rico y los Estados Unidos<br />

confrontando la relación colonial que existe hasta hoy en día y questionando el espacio entre<br />

ambas culturas. Combino temas de iconografía popular, folclórica, y del consumidor con nuevas<br />

jerarquías para describir la complejidad de creencia contemporános. Plátano puro es una serie<br />

de esculturas que celebra el plátano, un símbolo icónico y típico de Puerto Rico y el Caribe. En<br />

estas obras, los plátanos verdes reales fueron tratados con platino. Se convierten en joyas<br />

emblemáticas que trans<strong>for</strong>man estigmas culturales en expresiones de orgullo. Filiberto Ojeda<br />

Uptown/Machetero Air Force Ones (2007), es un par de zapatillas Nike que rinde homenaje al jefe<br />

asesinado de los Macheteros—un grupo clandestino y armado de nacionalistas Puertorriqueños<br />

que han luchado por la independencia de la isla desde la década de 1970.<br />

My work addresses playful and painful exchanges between Puerto Rico and the United States,<br />

questioning a colonial relationship that exists to present day while problematizing the space between<br />

both cultures. It often organizes popular, folkloric and consumer iconography into fluctuating new<br />

hierarchies to describe the complexity of contemporary belief systems. Pure Plantainum is a sculptural<br />

series of works that commemorate the plantain, a stereotypical yet iconic Puerto Rican and Caribbean<br />

symbol. In these works, actual green plantains were plated in platinum. They become emblematic<br />

jewels that trans<strong>for</strong>m cultural stigmas in to urban expressions of pride. The Filiberto Ojeda<br />

Uptowns/Machetero Air Force Ones (2007) are a customized pair of Nike sneakers that pay tribute to the<br />

assassinated leader of the Macheteros (machete wielders)—an armed clandestine group of Puerto<br />

Rican nationalists who’ve campaigned <strong>for</strong> independence in Puerto Rico since the 1970s.<br />

42

Filberto Ojeda Uptowns/<br />

Machetero Air Force Ones, 2007<br />

Thermal transfer and acrylic on<br />

custom sneakers<br />

5x91/2 x111/2 inches<br />

44

Plátanos (plantains) in Plaza del<br />

Mercado de Santurce, Puerto Rico<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

45

JEANNINE MARCHAND<br />

Polipo, 2006<br />

White earthenware, paint<br />

7x 20 x 20 inches<br />

Creciendo en la isla de Puerto Rico con el sol, la arena, el océano y la naturaleza, mis memorias<br />

de niñez están llenas de luces y sombras de <strong>for</strong>mas y emociones. La sensualidad es mi idioma,<br />

encontrando una voz en <strong>for</strong>ma de arcilla blanca maleable. El recuerdo y las emociones filtrados<br />

son extractados y esculpidos por las manos en un proceso puramente intuitivo. La sensualidad<br />

y la memoria son el concepto central de mi trabajo. Estas obras <strong>for</strong>man parte de una colección<br />

de recuerdos oceánicos que se están encontrados con y registrados por la memoria.<br />

Growing up on the Island of Puerto Rico with the sun, sand, ocean and nature, my childhood memories<br />

are filled with the lights and shadows of <strong>for</strong>ms and emotions. Sensuality is my language, finding voice<br />

in the <strong>for</strong>m of malleable white clay. Filtered recollections and emotions are abstracted and sculpted<br />

through my hands in a purely intuitive process. Sensuality and memory are the very heart and core<br />

of my work.These works are part of a collection of oceanic memorabilia encountered and recorded<br />

by memory.<br />

46

Espiga, 2006<br />

Red and white earthenware, paint<br />

7x34x43/4 inches<br />

48

Moonrise at Bren ~ as<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

49

RAQUEL QUIJANO<br />

FELICIANO<br />

Andamios II, 2008<br />

Sintra, printed on paper<br />

15 x 10 x 5 inches<br />

Mi trabajo con cubos geométricos de papel y Sintra se ha creado en respuesta a nuestros<br />

desarrollos urbanos constantemente cambiantes y los grandes edificios herméticos que nos<br />

hacen pensar que vivimos entre circuitos y sistemas industrializados. El objetivo de este nuevo<br />

trabajo es de lograr un nuevo estético en el grabado que utiliza un enfoque conceptual.<br />

My work with geometric paper cubes and Sintra has been created in response to our constantly changing<br />

urban developments and the large hermetic buildings that cause us to think we live between circuits<br />

and industrialized systems.The objective of this new work is to achieve a new aesthetic in engraving<br />

using a conceptual approach.<br />

50

Industrial building<br />

SOURCE<br />

▼<br />

Andamios I, 2008<br />

Sintra, printed on paper<br />

7 x13 x10 inches<br />

52

FRANCO MONDINI-RUIZ<br />

Baby Mojado, 2005<br />

Found and altered materials<br />

6 x 4 x 4 inches<br />

Courtesy of Frederieke Taylor Gallery, New York, NY<br />

Yo he conocido a un fotógrafo meticuloso de Europa que quiere explorar el mundo de los<br />

vaqueros en su nueva serie. La cafeína de mi café acaba de funcionar y abro la boca grande,<br />

gorda y enojada y despotrico acerca de cómo esos vaqueros blancos de las películas<br />

occidentales de Roy Rogers nunca existieron realmente en el sur de Tejas. La mayor parte<br />

del trabajo en estas partes fue hecha por los mexicanos y los negros. “Hoy en día es espalda<br />

mojada," digo yo, lo provocando con esa palabra fea por los mexicanos sin documentación que<br />

a veces recurren a nadar al otro lado del Rio Grande para encontrar el trabajo en este país.<br />

El fotógrafo fotografia estos tipos muy bien, sus chozas barrocas, sus pavos reales domésticos,<br />

sus camisas favoritas, sus coches destartalados. Yo sólo puedo imaginarme cuán útil y cortés<br />

ellos estuvieron a él, con sus saludos agradables con la cabeza. Pero no veo ninguno de ellos en<br />

el estreno o en la fiesta glamorosa que siguió—sólo los Anglos que poseen las haciendas en las<br />

cuales trabajan. Quizá llegué demasiado tarde. Quizá nadie se tomó la molestia de invitarlos.<br />

I have become acquainted with a fastidious European photographer who wants to explore the world<br />

of cowboys in his new series. My coffee is just kickin’ in and I open my big, fat, angry mouth and go<br />

on a rant about how those white, Roy Rogers western movie cowboys never really existed in South<br />

Texas. Most of the labor in these parts was done by Mexicans and blacks. “Nowadays it’s<br />

wetbacks,” I say, provoking him with that ugly word <strong>for</strong> undocumented Mexicans who sometimes<br />

resort to swimming across the Rio Grande in order to get work in this country. The photographer<br />

does a gorgeous job photographing these guys, their baroque shacks, their pet peacocks, their favorite<br />

shirts, their junked cars. I can only imagine how helpful and polite they were to him, with their agreeable<br />

tea-party nods. But I don’t see any of them at the show opening or the glamorous party that followed<br />

— only the Anglos who own the ranches they work on. Maybe I arrived too late. Maybe no<br />

one bothered to invite them.<br />

Excerpt from High Pink:Tex-Mex Fairy Tales by Franco Mondini-Ruiz<br />

Desde que abandonó una carrera como un abogado exitoso en San Antonio, Franco Mondini-<br />

Ruiz se ha dedicado completamente al hacer del arte. Reconociendo su identificación como un<br />

latino asimilado y manteniendo conexiones a través de fronteras étnicas Mondini-Ruiz-por sus<br />

colecciones de figurillas y viandas-crea objetos culturalmente ricos que comparten narrativas<br />

históricas, étnicas, sexuales y religiosas y establecen una confluencia de mundos que reflejan el<br />

uno al otro para siempre.<br />

Since abandoning a career as a successful lawyer in San Antonio, Franco Mondini-Ruiz has devoted<br />

himself full-time to the making of art. Acknowledging his identification as an assimilated Latino<br />

and maintaining connections across ethnic boundaries Mondini-Ruiz-through his assemblages of<br />

figurines and victuals—creates culturally rich objects sharing historical, ethnic, sexual, and religious<br />

narratives and setting up a confluence of worlds mirroring one another into infinity.<br />

54

Muffin Man, 2005<br />

Found and altered materials<br />

8 x 3 x 3 inches<br />

Courtesy of Frederieke Taylor Gallery, New York, NY<br />

56

Installation, mixed media, 2007<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

57

COURTNEY SMITH<br />

Mi trabajo con muebles comenzó en Brasil, donde viví y trabajé durante los primeros 12 años de<br />

mi carrera. Me facinaban los trozos desechados y obsoletos de muebles de principio del siglo XX<br />

que llenaban las sucias tiendas de objetos usados en Rio de Janeiro. Cada mueble era una fusion<br />

de estilos europeos interpretados de variadas <strong>for</strong>mas, trasladados a esquisitas maderas tropicales<br />

y finamente moldeados en la tradición del trabajo con madera portugués. Un objeto como<br />

este — que en algunos idiomas es llamado “mueble” (opuesto a una casa que es llamada<br />

“inmueble”) — para mí es un símbolo mutable del cuerpo y su hogar, que literalmente habita el<br />

espacio que esta entre medio de ambos.<br />

Polly Blue Pell Mell es un tocador brasileño de 1950 con mesas para sus costados del mismo<br />

estilo, cortadas y luego reconstruidas en mesas apilables, ensamblando sus bloques. Las partes<br />

nuevas o ‘‘artificiales’’ de la obra son señaladas por una piel azul de Formica que cubre las<br />

superficies interiores. La escultura funciona como un conjunto de componentes, y puede ser<br />

montada como un rompecabezas o completamente desmontado y dispersada enmontones de azul.<br />

My work with furniture began in Brazil, where I lived and worked <strong>for</strong> the first 12 years of my career.<br />

I became fascinated with the discarded, obsolete pieces of early twentieth century furniture cluttering<br />

the gritty junk stores of Rio de Janeiro. Each piece was a fusion of various interpreted European styles,<br />

translated into exquisite tropical woods and finely crafted in the tradition of Portuguese woodworking.<br />

A piece of furniture — which in some other languages is called a “movable” (as opposed to the house<br />

called the “unmovable”)— is to me a mutable symbol <strong>for</strong> both the body and its home, literally<br />

inhabiting the space in between.<br />

Polly Blue Pell Mell is a 1950’s Brazilian dresser with matching side tables cut into pieces that are then<br />

reconstructed into stackable, interlocking blocks.The new or ‘artificial’ parts of the work are signaled<br />

by a blue Formica skin, that lines the interior surfaces. The sculpture functions as a set of building<br />

blocks, and can be assembled like a puzzle, or fully disassembled and spread out into piles of blue.<br />

58

Polly Blue Pell Mell, 2005<br />

1950s wood vanity, side tables from Brazil,<br />

plywood, blue plastic laminate<br />

36 x 71 x 20 inches<br />

59

Santo Antonio, 2003<br />

Chest of drawers from Brazil, plywood<br />

32 x 58 x 20 inches<br />

60

Sketchbook drawings<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

61

WALKA STUDIO<br />

CLAUDIA BETANCOURT<br />

RICARDO PULGAR<br />

Siendo la tercera generación de artesanos chilenos, nuestro ingreso a la orfebrería contemporánea<br />

es a través de la artesanía. Nuestro interés se centra en la identidad cultural (mestizaje),<br />

comoditización de la artesanía, arte colaborativo, la relación entre la cultural visual local y globalización,<br />

y las relaciones que se generan entre arte-artesanía-diseño. Los pájaros cantan en<br />

pajarístico pero los escuchamos en español! Es parte de una serie de obras que remite a las precarias<br />

condiciones de trabajo en nuestro país. El ‘‘canario cantor’’ representa una especie de libertad<br />

atrapada o perdida. La jaula, en bronce bañado en oro, representa el común doble estándar<br />

de nuestra sociedad. También, ella se refiere a cómo el consumismo y la comoditización, de<br />

la artesanía y otros rubros, generan dicho encierro.<br />

As third generation traditional Chilean makers, we arrive at contemporary jewelry through craft. Our<br />

work focuses on cultural identity (mestizaje), craft commoditization, collaboration, relations between<br />

globalization and local visual identity and art-craft-design relationships. Los pájaros cantan en pajarístico<br />

pero los escuchamos en español Chile: Get Out From the Cage! is one of a series of works referencing the<br />

precarious working conditions in Chile.The bird represents a kind of liberty caught.The cage is made<br />

of gilded bronze, representing a double standard in Chile’s work <strong>for</strong>ce and how consumerism and<br />

commoditization have become like ‘cages.’<br />

62

Los pájaros cantan en pajarístico<br />

pero los escuchamos en español<br />

Chile: Get Out From the Cage!<br />

Plastic, bronze, gold, lapis lazuli<br />

3 x 2 x 2 inches<br />

63

I Am Not a Plastic Bag: Bracelet, 2008<br />

Silver, plastic polymer<br />

6 1/2 x 4 x 1/2 inches<br />

64

A street vendor in Chile selling plastic bird whistles<br />

▼<br />

SOURCE<br />

65

ARTIST<br />

BIOGRAPHIES<br />

ALEJANDRO AGUILERA<br />

Born: Holguin, Cuba, 1964<br />

Lives: Atlanta, Georgia, USA<br />

Education<br />

Postgraduate Fellowship, Massachusetts College of Art,<br />

Boston, MA, USA 1990<br />

MFA, Instituto Superior de Arte, Havana, Cuba, 1989<br />

BFA, Escuela de Arte, Holguin, Cuba, 1983<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2007<br />

A Brief History of Usage, solo exhibition, Bernice<br />

Steinbaum Gallery, Miami, FL, USA<br />

2006<br />

Forty Yards of Lines, solo exhibition, Georgia College<br />

and State University, Milledgeville, GA, USA<br />

2004<br />

A.A Recent Work, solo exhibition, Gallery Sklo,<br />

Atlanta, GA, USA<br />

Re-defining Georgia, The Columbus Museum,<br />

Columbus, GA, USA<br />

The Art of Making Art, solo exhibition, Ty Stokes<br />

Gallery, Atlanta, GA, USA<br />

2003<br />

A.A. A Decade of Assemblages, solo exhibition,<br />

University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA<br />

Atlanta Biennial, The Atlanta <strong>Contemporary</strong> Art Center,<br />

Atlanta, GA, USA<br />

Selected Collections<br />

Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA<br />

Museum of <strong>Contemporary</strong> Art, MARCO, Monterrey,<br />

Mexico<br />

National Museum Palace of Fine Arts, Havana, Cuba<br />

ELIA ALBA<br />

Born: New York, NY, USA, 1962<br />

Lives: Brooklyn, NY, USA<br />

Education<br />

Whitney Museum, Independent Study Program,<br />

of American Art, New York, NY, USA, 2001<br />

BA, Hunter College, New York, NY, USA, 1994<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2009<br />

10th Havana Biennial, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo<br />

Wifredo Lam, Cuba<br />

Entre-Vues: <strong>Contemporary</strong> Photography from the<br />

Caribbean, Fondation Clement, Martinique<br />

2008<br />

Archaeology of Wonder, Real Art Ways, Hart<strong>for</strong>d,<br />

CT, USA<br />

Visionarios, Audiovisual En Latinoamérica, ITAU Cultural<br />

Institute, Sao Paolo, Brazil<br />

Ethnographies of the Future, Rotunda Gallery, New York,<br />

NY, USA<br />

LOOP 08, Barcelona, Spain<br />

2007<br />

UltraMar, Instituto Cervantes de São Paulo, Brazil<br />

(traveling)<br />

Agua, Cuarto Espacio Cultural. Diputación de Zaragoza,<br />

Spain<br />

66

2006<br />

Close Connections, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam,<br />

Netherlands<br />

This Skin I’m in, El Museo del Barrio, New York, NY, USA<br />

Queens International 06: Everything All At Once,<br />

Queens Museum of Art, Queens, NY, USA<br />

Tropicalisms: Subversions of Paradise, Jersey City<br />

Museum, Jersey City, NJ, USA<br />

REWIND… REWIND, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña,<br />

San Juan, Puerto Rico<br />

Selected Grants and Awards<br />

2008<br />

Grant, Joan Mitchell Foundation, Inc.,<br />

New York, NY, USA<br />

Fellowship, New York Foundation <strong>for</strong> the Arts,<br />

New York, NY, USA— Photography<br />

2003<br />

Grant, The Pollack-Krasner Foundation, New York,<br />

NY, USA<br />

Selected Collections<br />

Jersey City Museum, Jersey City, NJ, USA<br />

El Museo del Barrio, New York, NY, USA<br />

Lowe Art Museum, Miami, FL, USA<br />

Museo de Arte Moderno, Santo Domingo,<br />

Dominican Republic<br />

PEDRO CRUZ-CASTRO<br />

Born: Caracas, Venezuela, 1970<br />

Lives: Brooklyn, NY, USA<br />

Education<br />

BA, Jose Maria Vargas University, Caracas,<br />

Venezuela, 1991<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2008<br />

In<strong>for</strong>med by Function, Lehman College Art Gallery,<br />

New York, NY, USA<br />

Leckerbissen, Gallery Na Kashirke, Moscow, Russia<br />

Threading Trends, Galerie AltePost, Berlin, Germany<br />

2007<br />

Reclamation, Sunroom Project at Wave Hill,<br />

New York, NY, USA<br />

The Carriage House, Islip Art Museum, New York,<br />

NY, USA<br />

The (S) Files/The Selected Files, El Museo del Barrio,<br />

New York, NY, USA<br />

TidBit, GalerieR31, Berlin, Germany<br />

2006<br />

AIM 26, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York,<br />

NY, USA (catalogue)<br />

Icons, Werketage, Berlin, Germany<br />

Selected Grants and Awards<br />

2000<br />

‘‘Change’’ Grant, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation,<br />

Captiva, FL, USA<br />

SUSANA ESPINOSA<br />

Born: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1933<br />

Lives: San Juan, Puerto Rico<br />

Education<br />

BFA, la Academia de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires,<br />

Argentina, 1953<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2008<br />

Colección Reyes-Veray, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo,<br />

San Juan, Puerto Rico<br />

La Vasija, Galería Gandía, San Juan, Puerto Rico<br />

2007<br />

Casa Candina, Universidad del Turabo, Gurabo,<br />

Puerto Rico<br />

Muestra Nacional de Artes Plásticas, San Juan,<br />

Puerto Rico<br />

2005<br />

Appearances and Presences, solo exhibition, Couturier<br />

Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA<br />

Selected Collections<br />

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico,<br />

San Juan, Puerto Rico<br />

Museo de la Cerámica, Ichon, Japan<br />

Museo de la Cerámica: Mimara, Zagreb, Yugoslavia<br />

Museum of Latin American Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA<br />

Museo della Ceramica D’arte de Faenza, Faenza, Italy<br />

OVIDIO GIBERGA<br />

Born: Washignton, DC, USA, 1965<br />

Lives: San Antonio, Texas, USA<br />

Education<br />

MFA, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 1996<br />

BA, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL,<br />

USA, 1991<br />

Associates, Miami Dade Community College,<br />

Miami, FL, USA, 1988<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2008<br />

Arte Nuevo, 1604 Gallery, San Antonio, TX, USA<br />

Northwest Connection; <strong>Contemporary</strong> Works in Clay,<br />

Esvelt Gallery, Columbia Basin College, Pasco, WA, USA<br />

Ovidio Giberga, solo exhibition, Blue Star <strong>Contemporary</strong><br />

Art Center, San Antonio, TX, USA<br />

Surface, Form and Substance, Amaco/Brent<br />

<strong>Contemporary</strong> Clay Gallery, Indianapolis, IN, USA<br />

2007<br />

<strong>Craft</strong>Forms 2007, Wayne Art Center, Wayne, PA, USA<br />

From the Ground Up, Las Cruces Museum of Art,<br />

Las Cruces, NM, USA<br />

Visions and Voices, Kentucky Museum of Art and <strong>Craft</strong>,<br />

Louisville, KY, USA<br />

2006<br />

<strong>Craft</strong>Houston 2006, Houston Center <strong>for</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong><br />

<strong>Craft</strong>, Houston, TX, USA<br />

Viewpoint: Ceramics 2006, Hyde Art Gallery, Grossmont<br />

College, El Cajon, CA, USA<br />

Selected Collections<br />

Archie Bray Foundation, Helena, MT, USA<br />

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA<br />

67

Selected Grants and Awards<br />

2004 Scholarship/Creativity Grant, Watershed Center <strong>for</strong><br />

the Ceramic Arts, Newcastle, ME, USA<br />

Selected Bibliography<br />

Northway, Paul. ‘‘Finding A Balance.’’ Ceramics Monthly,<br />

April 2008<br />

Poellot, Jennifer. ‘‘The Slip-Cast Object.’’<br />

Ceramics Monthly, May 2005<br />

Toutillott, Suzanne. Editor. ‘‘The Figure in Clay.’’<br />

(Lark Books, Ashville, North Carolina, USA, 2005)<br />

TAMARA KOSTIANOVSKY<br />

Born: Jerusalem, Israel, 1974<br />

Lives: Brooklyn, NY, USA<br />

Education<br />

MFA, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,<br />

Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003<br />

BFA, Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, ‘‘Prilidiano<br />

Pueyrredón,’’ Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1998<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2008<br />

Actus Reus, solo exhibition, Black & White<br />

Gallery//Chelsea, New York, NY, USA<br />

El Ultimo Libro, Biblioteca Nacional de Buenos Aires,<br />

Buenos Aires, Argentina<br />

Meat After Meat Joy, Daneyal Mahmood Gallery,<br />

New York, NY, USA<br />

Outside Over There, Gallery Aferro, Newark, NJ, USA<br />

Scope Miami, Y Gallery, Miami, FL, USA<br />

2007<br />

The (S) Files 007, El Museo del Barrio, New York,<br />

NY, USA<br />

Yo! <strong>Contemporary</strong> Self Portraits, Solar Gallery,<br />

East Hampton, NY, USA<br />

Selected Collections<br />

El Museo del Barrio, New York, NY, USA<br />

Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art Congregation<br />

Rodeph Shalom, Philadelphia, PA, USA<br />

Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires,<br />

Argentina<br />

Selected Grants and Awards<br />

2009<br />

Swing Space, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council,<br />

New York, NY, USA<br />

2008<br />

Grant, The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York,<br />

NY, USA<br />

2005<br />

SOS Grant, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts,<br />

Harrisburg, PA, USA<br />

Selected Bibliography<br />

Harmon, Kitty. CARTOGRAPHY: Artists + Maps.<br />

(New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009)<br />

Trong, Nguyen G. ‘‘Interview with Tamara<br />

Kostianovsky.’’ ARTslantcom, January 2009<br />

Fulmer, Dick. ‘‘Carne-Diem — What Meat Art Can Tell Us<br />

About Art and Death.’’ Meatpaper. (Issue 5, Fall 2008)<br />

McQuaid, Cate. ‘‘In Exhibit Devoted to Meat, Some<br />

Offerings Are a Cut Above.’’ The Boston Globe.<br />

July 2, 2008<br />

SILVIA LEVENSON<br />

Born: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1957<br />

Lives: Lesa, Italy<br />

Education<br />

Self taught<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2008<br />

Flux, Reflections in <strong>Contemporary</strong> Glass, New Mexico<br />

Museum of Art, Santa Fe, NM, USA<br />

The Kitchen, El Corazon de la Casa. Galeria Montoriol,<br />

Barcelona, Spain<br />

You are not living alone…. solo exhibition, Bullseye<br />

Gallery, Portland, OR, USA<br />

2006<br />

Algo anda Mal, Embassy of Argentina, Rome, Italy<br />

<strong>Contemporary</strong> Kiln Glass, University of Miami, College<br />

of Arts and Sciences Gallery, Miami, FL, USA<br />

<strong>Craft</strong>ing a Collection, The Museum of Fine Arts,<br />

Houston, TX, USA<br />

Plaza de Mayo, solo exhibition, Galleria Traghetto,<br />

Rome, Italy<br />

Something’s Wrong, Galleria Arthobler, Porto, Portugal<br />

2005<br />

I see you are a bit nervous, solo exhibition, Bullseye<br />

Connections Gallery. Portland, OR, USA<br />

Selected Collections<br />

Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, USA<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, USA<br />

New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fè, NM, USA<br />

Museo Catelvetro. Castelvetro, Italy<br />

Tikanoja Art Museum, Vaasa, Finland<br />

Musée-atelier du Verre à Sars-Poteries,<br />

Sars-Poteries, France<br />

Ernsting Glass Collection, Coesfeld, Germany<br />

Glasmuseum, Ebeltoft, Denmark<br />

Museo Leon Rigaulleau, Buenos Aires, Argentina<br />

Museo del Vetro, Altare, Italy<br />

MIGUEL LUCIANO<br />

Born: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1972<br />

Lives: Brooklyn, New York, USA<br />

Education<br />

MFA, University of Florida at Gainesville, FL, USA, 2000<br />

BFA, New World School of the Arts, Miami, FL,<br />

USA, 1997<br />

Selected Exhibitions<br />

2009<br />

Kréyol Factory, La Grande Halle de la Villette,<br />

Paris, France<br />

Puerto Rico: Human Geography, The Smithsonian<br />