Ingrid Jacoby - International Classical Artists

Ingrid Jacoby - International Classical Artists

Ingrid Jacoby - International Classical Artists

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

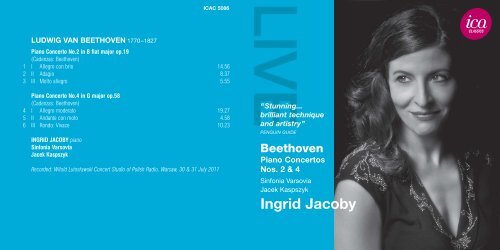

ICAC 5086<br />

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770–1827<br />

Piano Concerto No.2 in B flat major op.19<br />

(Cadenzas: Beethoven)<br />

1 I Allegro con brio 14.56<br />

2 II Adagio 8.37<br />

3 III Molto allegro 5.55<br />

Piano Concerto No.4 in G major op.58<br />

(Cadenzas: Beethoven)<br />

4 I Allegro moderato 19.27<br />

5 II Andante con moto 4.58<br />

6 III Rondo: Vivace 10.23<br />

INGRID JACOBY piano<br />

Sinfonia Varsovia<br />

Jacek Kaspszyk<br />

Recorded: Witold Lutosl awski Concert Studio of Polish Radio, Warsaw, 30 & 31 July 2011<br />

/<br />

“Stunning...<br />

brilliant technique<br />

and artistry”<br />

PENGUIN GUIDE<br />

Beethoven<br />

Piano Concertos<br />

Nos. 2 & 4<br />

Sinfonia Varsovia<br />

Jacek Kaspszyk<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>

INGRID JACOBY PLAYS BEETHOVEN’S<br />

PIANO CONCERTOS NOS. 2 & 4<br />

Early in 1801 Beethoven offered his B flat Piano Concerto<br />

for sale to the Leipzig publisher Hoffmeister at the<br />

knockdown rate of ten ducats, ‘because I do not regard it<br />

as one of my best’. To us the concerto seems a youthful<br />

charmer, saturated with the spirit of Haydn and Mozart but<br />

teeming with original ideas and, in the rondo finale,<br />

Beethoven’s own brand of humour. ‘Underrated, delightful<br />

and full of life’, is <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>’s verdict. Yet by 1801<br />

Beethoven doubtless considered it old-fashioned:<br />

unsurprisingly, since he had begun the work back in 1788,<br />

completed a first version during the winter of 1794–5, and<br />

then revised it after giving the public premiere in 1795.<br />

True to form, though, he only wrote out the piano part just<br />

before it was published, as No.2, in 1801. Until then he<br />

had played it from memory, thereby ensuring that no rival<br />

could ‘steal’ the concerto.<br />

The concerto’s opening – a brusque summons followed<br />

by a pleading response – is an arresting take on a favourite<br />

Mozartian gambit. But later, where Mozart would have<br />

introduced a new tune, Beethoven plunges into the remote<br />

key of D flat to develop the main theme’s beseeching<br />

answering phrase. This surprise move to D flat has<br />

consequences when the soloist later introduces a<br />

mysterious new theme in this key – an early example of<br />

Beethoven’s concern for long-range tonal planning. ‘He’s<br />

taking lessons from Mozart here’, says <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>. ‘But<br />

the movement is pure Beethoven: more modern in feeling,<br />

that much denser and more brilliant in its piano textures.<br />

And the huge cadenza, written much later, in 1809, is as<br />

un-Mozartian as you can get. It even has elements of the<br />

late sonatas: the fugal beginning, the use of the keyboard’s<br />

extremes, and the way it develops the themes.’<br />

2<br />

The noble theme of the E flat Adagio, somewhere<br />

between an aria and a hymn, has that exalted simplicity<br />

typical of Beethoven’s early slow movements. Equally<br />

typically, Beethoven then embellishes this melody with<br />

increasingly lavish figuration, just as an operatic heroine<br />

would decorate a slow cantilena; and we can be sure that<br />

he improvised these embellishments differently each time<br />

he played the concerto. Adds <strong>Jacoby</strong>: ‘With its rich<br />

textures and suspensions this Adagio is typical of<br />

Beethoven’s early slow movements. And at the end, we<br />

have an amazing, highly emotional recitative, marked con<br />

gran espressione and enhanced by the resonance of the<br />

sustaining pedal. Here, more than anywhere, Beethoven<br />

goes into his own sound world.’<br />

Mozart liked to end his B flat concertos with huntingstyle<br />

rondos in 6/8 time. Beethoven’s finale follows suit,<br />

though he adds his own subversive twist by peppering his<br />

catchy main theme with offbeat accents. There are more<br />

rhythmic dislocations in the central episode, where the<br />

theme is treated to boogie-like syncopations. ‘It’s<br />

Beethoven at his most boisterously humorous,’ says<br />

<strong>Jacoby</strong>. ‘The theme is so simple, yet in this middle section<br />

he enjoys poking fun at it with all those syncopations and<br />

harmonic dissonances.’ Perhaps the wittiest stroke comes<br />

in the coda where the piano slips nonchalantly into G<br />

major for a smoothed-out version of the rondo theme<br />

before the orchestra noisily intervenes with the tune in its<br />

original, unruly form.<br />

Beethoven’s so-called middle period – corresponding<br />

roughly to the decade from 1803 – is famously associated<br />

with the notion of heroic struggle. But the image of the<br />

furrow-browed Titan forging mighty, dynamic structures<br />

is far from the whole picture. Just as characteristic are<br />

works where the expanded scale of Beethoven’s thinking<br />

goes hand in hand with a new lyric breadth and tranquillity:<br />

the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony, the Violin Concerto and the<br />

Fourth Piano Concerto, in their way just as revolutionary<br />

as the ethically charged strivings of the ‘Eroica’ and<br />

Fifth Symphonies.<br />

After making brief sketches in 1804, Beethoven turned<br />

to the G major Concerto in earnest during 1806, when<br />

the Fifth Symphony was also on the stocks; and it is surely<br />

no coincidence that their first movements view the same<br />

four-note figure from a drastically different perspective. As<br />

<strong>Jacoby</strong> puts it: ‘In the symphony Beethoven compresses<br />

and contracts. In the concerto he does the opposite,<br />

and serenely expands the opening motif.’ The composer<br />

himself gave the public premiere in his gargantuan benefit<br />

concert in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien on 22 December<br />

1808 that also included the first performances of the<br />

‘Pastoral’ and Fifth Symphonies, parts of the Mass in C<br />

and the Choral Fantasy. Reports of the concert are scant,<br />

though the composer J.G. Reichardt, who was present in<br />

the freezing theatre, noted ‘a new fortepiano concerto of<br />

monstrous difficulty, which Beethoven played astonishingly<br />

well at the fastest possible speeds’.<br />

The concerto begins, unprecedentedly, with an<br />

exquisitely gentle theme for the soloist alone, richly<br />

scored in the keyboard’s resonant middle register. ‘While<br />

it sounds simple, this poetic opening is deceptively<br />

difficult,’ says <strong>Jacoby</strong>. ‘It demands perfect control of<br />

sound, the most precise balancing of chords. It reminds<br />

me of Schnabel’s remark that great music is greater than<br />

it can ever be played.’<br />

Although the movement has its bouts of virtuoso<br />

brilliance, as that first reviewer suggested, the predominant<br />

tone is one of confiding tenderness. Time and again<br />

the piano quietly deflects the orchestra’s propensity<br />

to vigorous assertion, with prepared climaxes tending<br />

to dissolve into lyrical meditation. At the end of the<br />

3<br />

exposition, for instance, a long trill leads us to expect a<br />

rousing orchestral tutti. But Beethoven foils expectations in<br />

a haunting passage where the soloist muses quietly on a<br />

cadential theme first heard in the orchestral introduction.<br />

The piano likewise takes the role of gentle appeaser in<br />

the theatrically conceived Andante con moto. Beethoven’s<br />

nineteenth-century biographer A.B. Marx aptly compared<br />

this movement to Orpheus’s taming of the Furies. It can<br />

also be heard as the confrontation of two musical worlds:<br />

Baroque rigour in the strings’ brusque unisons, in dotted<br />

rhythm (the first phrase could have stepped from a tragic<br />

Handelian scena), Romantic pathos in the keyboard’s soft<br />

harmonised responses. ‘Beethoven stipulates the una<br />

corda, or soft, pedal until near the end,’ observes <strong>Jacoby</strong>,<br />

‘which gives the music a wonderful veiled quality.’<br />

Gradually the orchestra’s harshness is quelled by the<br />

piano’s increasingly eloquent pleas. Finally, the keyboard<br />

asserts its pre-eminence in an impassioned cadenza-like<br />

climax, with a fortissimo sustained trill, before the dotted<br />

rhythms are reduced to a ghostly whisper in the bass.<br />

The Andante barely leaves the key of E minor. The<br />

Rondo, which enters softly without a break, re-establishes<br />

G major via several bars of C major: the kind of witty<br />

off-key opening Beethoven learned from Haydn. For all<br />

its swagger and playfulness, this finale shares the first<br />

movement’s core of rich, tranquil lyricism: in the dolce<br />

second theme, announced by the soloist in two widely<br />

spaced contrapuntal lines over a deep pedal point; and in<br />

the beautiful transformations of the main theme towards<br />

the end of the movement, first on divided violas in a<br />

distant E flat, then, after the cadenza, in canon between<br />

piano and clarinets, where, at last, it appears unequivocally<br />

in the home key of G major before the galloping Presto<br />

send-off . As <strong>Jacoby</strong> puts it, this whole finale is ‘lifeaffirming<br />

music of joyous strength and propulsive energy

that demands a huge range of sound quality. Beethoven<br />

had come through the crisis of his deafness – he, more<br />

than most, understood suffering. It is perhaps one aspect<br />

of his genius that enabled him to transform tragedy into<br />

beauty and even triumph.’<br />

© Richard Wigmore<br />

INGRID JACOBY<br />

Praised by The New York Times for her ‘clear articulation<br />

… unequivocal phrasing … [and] expressivity’, <strong>Ingrid</strong><br />

<strong>Jacoby</strong> has established herself as one of the most poetic<br />

and admired pianists of her generation.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> began her piano studies with Larisa<br />

Gorodecka, herself a pupil of Heinrich Neuhaus. Graduating<br />

at 16 with highest honours from the St Louis Conservatory<br />

of Music <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> went on to win the National Baldwin<br />

Piano Competition, the Concert <strong>Artists</strong> Guild <strong>International</strong><br />

Piano Competition and the Steinway Hall <strong>Artists</strong> Prize.<br />

In America, the National Society of Arts and Letters<br />

awarded to her one of its highest distinctions, the Lifetime<br />

Achievement Award.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> has performed in concerts around the<br />

world, playing with major orchestras under the direction of<br />

conductors such as Sir Charles Mackerras, Leonard Slatkin,<br />

Giuseppe Sinopoli, Walter Susskind and Lord Yehudi<br />

Menuhin. Ms. <strong>Jacoby</strong> has performed at international music<br />

festivals including at Aldeburgh, Aspen, Tuscan Sun, and<br />

Salzburg, where she performed Mozart in the Mozarteum.<br />

A wide and fascinating range of repertoire is covered<br />

in <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>’s discography, including the world<br />

premiere recording of Korngold’s solo piano pieces, works<br />

of Gershwin and Bernstein with the Russian National<br />

Orchestra, and a recording of the Shostakovich and<br />

Ustvolskaya piano concertos with the Royal Philharmonic<br />

Orchestra conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras which<br />

earned the highest commendation from the American<br />

Record Guide.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> comes from a family with deep<br />

musical roots; she is directly descended from the<br />

pianist, composer and Prussian nobleman, Prince Louis<br />

Ferdinand (1772–1806), to whom Beethoven dedicated<br />

his Third Piano Concerto. Prince Louis Ferdinand was<br />

the nephew of Frederick the Great, himself the composer<br />

of the famous theme which J.S. Bach used in his sublime<br />

Musical Offering.<br />

INGRID JACOBY JOUE LES DEUXIÈME ET<br />

QUATRIÈME CONCERTOS DE BEETHOVEN<br />

Début 1801, Beethoven proposait son Concerto pour<br />

piano en si bémol majeur à Hoffmeister, éditeur à<br />

Leipzig, au prix ridicule de dix ducats – “parce que je<br />

ne le considère pas comme l’un de mes meilleurs”,<br />

expliqua-t-il. Aujourd’hui, l’œuvre nous paraît pleine de<br />

charme juvénile : si elle véhicule l’esprit de Haydn et<br />

Mozart, elle fourmille d’idées originales et l’humour du<br />

rondo finale porte bien la marque de Beethoven. Pour<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>, ce concerto est “sous-estimé, charmant<br />

et plein de vie”. Pourtant, il ne fait pas de doute que<br />

Beethoven le trouvait désuet en 1801. Cela ne surprendra<br />

pas, car il l’avait entrepris en 1788, achevé une première<br />

version durant l’hiver 1794–1795, puis l’avait révisé<br />

après en avoir donné la première audition publique en<br />

1795. Fidèle à son habitude, ce n’est que juste avant<br />

de le publier, en 1801, avec le numéro 2, qu’il écrivit<br />

intégralement la partie de piano. Jusque-là, il l’avait jouée<br />

de mémoire, assurant ainsi qu’aucun rival ne pourrait lui<br />

“voler” son œuvre.<br />

Les premières mesures – un brusque appel suivi<br />

d’une réponse implorante – réinterprètent de manière<br />

saisissante une entame favorite de Mozart. Plus loin,<br />

cependant, là où Mozart aurait introduit une nouvelle<br />

mélodie, Beethoven plonge dans la tonalité éloignée de<br />

ré bémol majeur pour développer la phrase suppliante<br />

du thème principal. Cette modulation surprenante vers<br />

ré bémol aura des conséquences lorsque le soliste<br />

énoncera un nouveau thème mystérieux dans cette tonalité<br />

– un des premiers exemples du souci de Beethoven de<br />

mettre en œuvre un plan tonal à grande échelle. “Il prend<br />

ici une leçon avec Mozart, explique <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>. Mais le<br />

mouvement est du pur Beethoven : il fait une impression<br />

4 5<br />

plus moderne, il est plus dense, et son écriture pianistique<br />

plus brillante. Et l’énorme cadence, écrite bien plus tard,<br />

en 1809, ne saurait être moins mozartienne. Elle renferme<br />

même des éléments des dernières sonates de Beethoven :<br />

le début fugué, l’utilisation des registres extrêmes du<br />

clavier, et la façon dont elle développe les thèmes.”<br />

Le noble thème de l’Adagio en mi bémol majeur, à<br />

mi-chemin entre l’air et le cantique, a cette simplicité<br />

sublime typique des premiers mouvements lents de<br />

Beethoven. De manière tout aussi typique, le compositeur<br />

orne ensuite cette mélodie par une écriture de plus en plus<br />

riche, exactement comme une cantatrice ornerait un air<br />

adagio – on peut d’ailleurs être sûr qu’il improvisait une<br />

ornementation différente chaque fois qu’il jouait le concerto.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> ajoute : “Par ses riches textures et ses<br />

respirations, cet Adagio est typique du premier Beethoven.<br />

Et à la fin, on tombe sur un récitatif étonnant, très émouvant,<br />

surmonté de l’indication con gran espressione, qui est<br />

rendu encore plus intense par la résonance de la pédale<br />

forte. Ici, plus que n’importe où ailleurs, Beethoven plonge<br />

dans son propre monde sonore.”<br />

Mozart aimait conclure ses concertos en si bémol<br />

majeur par un rondo à 6/8 évoquant la chasse. Beethoven<br />

lui emboîte le pas dans son finale, mais il donne un tour<br />

subversif à son refrain entraînant en ajoutant des accents<br />

sur les temps faibles. D’autres contrariétés rythmiques se<br />

font jour dans la partie centrale où le refrain est agrémenté<br />

de syncopes qui rappellent le boogie-woogie. “Beethoven<br />

se montre ici sous son jour humoristique le plus tapageur,<br />

explique <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>. Ce thème on ne peut plus simple,<br />

il s’amuse à s’en moquer dans la partie centrale à grand<br />

renfort de syncopes et de dissonances.” C’est peut-être<br />

dans la coda que l’on trouve le trait le plus amusant : le<br />

piano glisse nonchalamment en sol majeur pour faire<br />

entendre une version plus paisible du refrain, mais

l’orchestre intervient bruyamment en le reprenant dans sa<br />

forme débridée originale.<br />

On a l’habitude d’associer ce qu’il est convenu<br />

d’appeler la période médiane de Beethoven – qui<br />

correspond, en gros, aux années 1803–1812 – à la notion<br />

de lutte héroïque. Pour autant, l’image du titan aux sourcils<br />

froncés forgeant des structures puissantes et dynamiques<br />

ne représente qu’une partie du tableau. De façon tout aussi<br />

caractéristique, on trouve dans cette période des œuvres<br />

où la pensée beethovénienne s’exprime à plus grande<br />

échelle et s’accompagne d’un nouveau souffle lyrique et<br />

paisible. Ainsi la Symphonie pastorale, le Concerto pour<br />

violon et le Quatrième Concerto pour piano sont à leur<br />

manière tout aussi révolutionnaires que l’Héroïque et la<br />

Cinquième Symphonie avec leurs luttes monumentales.<br />

Après quelques brèves esquisses notées en 1804,<br />

Beethoven se lança véritablement dans le Concerto en<br />

sol majeur durant l’année 1806, alors qu’il avait déjà la<br />

Cinquième Symphonie sur le métier. Ce n’est d’ailleurs<br />

certainement pas une coïncidence si les deux œuvres<br />

utilisent le même motif de quatre notes dans leur premier<br />

mouvement, dans une perspective toutefois radicalement<br />

différente. Comme le fait remarquer <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>, “dans la<br />

symphonie, Beethoven comprime et resserre; dans le<br />

concerto, il fait l’inverse, il prolonge sereinement le motif<br />

initial”. Le compositeur lui-même donna la première audition<br />

publique du concerto le 22 décembre 1808, à Vienne, au<br />

Theater an der Wien, au cours d’un gigantesque concert à<br />

bénéfice où l’on entendit également pour la première fois<br />

la Symphonie pastorale, la Cinquième Symphonie, ainsi<br />

que des parties de la Messe en ut et la Fantaisie chorale.<br />

Si les comptes rendus du concert sont laconiques, on<br />

a tout de même une remarque du compositeur Johann<br />

Friedrich Reichardt, qui était présent dans le théâtre<br />

glacial, sur “un nouveau concerto pour pianoforte d’une<br />

6<br />

énorme difficulté que Beethoven a exécuté d’une manière<br />

étonnante à des tempi on ne peut plus rapides”.<br />

L’œuvre commence, de façon inédite, par une<br />

présentation, au piano seul, d’un thème d’une douceur<br />

exquise dans le médium riche et sonore de l’instrument.<br />

“Bien qu’il frappe par sa simplicité, ce début poétique est<br />

difficile, affirme <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>. Il requiert une parfaite<br />

maîtrise de la sonorité, les accords doivent être le plus<br />

équilibrés possible. Cela me rappelle une remarque de<br />

Schnabel qui disait que la grande musique est plus grande<br />

qu’on ne pourra jamais la jouer.”<br />

Si le mouvement renferme des passages virtuoses,<br />

comme le laisse entendre la remarque de Reichardt, le ton<br />

dominant est celui d’une tendresse confiante. De temps à<br />

autre, le piano sape en douceur la propension de<br />

l’orchestre à s’exprimer vigoureusement, les sommets<br />

d’intensité, dûment préparés, tendant à se dissoudre dans<br />

une méditation lyrique. À la fin de l’exposition, par<br />

exemple, un long trille semble annoncer un grand tutti<br />

orchestral. Beethoven déjoue cependant les attentes avec<br />

un passage envoûtant où le soliste s’épanche<br />

tranquillement sur un thème cadentiel entendu pour la<br />

première fois dans l’introduction orchestrale.<br />

Fidèle à son rôle, le piano continue d’apporter<br />

l’apaisement en douceur dans l’Andante con moto, conçu<br />

de manière théâtrale. En un rapprochement pertinent, le<br />

biographe de Beethoven Adolf Bernhard Marx (1795–1866)<br />

a vu dans ce mouvement Orphée domptant les furies. On<br />

peut aussi y entendre la confrontation entre deux mondes<br />

musicaux : la rigueur baroque dans les brusques unissons<br />

des cordes en rythmes pointés (la première phrase pourrait<br />

être sortie d’une scène tragique de Haendel), le pathos<br />

romantique dans les réponses doucement harmonisées du<br />

piano. “Beethoven requiert la pédale una corda, c’est-à-dire<br />

la pédale douce, jusqu’à la fin pratiquement, note <strong>Ingrid</strong><br />

<strong>Jacoby</strong>, ce qui donne à la musique un caractère voilé<br />

merveilleux.” Petit à petit, la sévérité de l’orchestre est<br />

tempérée par les appels de plus en plus éloquents du<br />

piano. Finalement, le piano affirme sa prééminence dans<br />

un sommet passionné, de type cadence, sur un trille<br />

fortissimo, avant que les rythmes pointés ne soient réduits<br />

à un murmure fantomatique aux basses.<br />

L’ Andante ne quitte pratiquement pas la tonalité de<br />

mi mineur. Sans interruption, le Rondo entre doucement et<br />

installe à nouveau sol majeur en passant par plusieurs<br />

mesures d’ut majeur : c’est le genre de début humoristique<br />

dans la “fausse” tonalité que Beethoven avait appris de<br />

Haydn. Malgré ses fanfaronnades et son caractère enjoué,<br />

ce finale a en commun avec le premier mouvement un<br />

lyrisme riche et paisible en son cœur : dans le deuxième<br />

thème dolce, un contrepoint, exposé par le soliste, de deux<br />

voix très espacées sur une pédale grave; et dans les<br />

magnifiques métamorphoses du thème principal, la<br />

première vers la fin du développement, où il est présenté<br />

aux altos divisés dans un mi bémol lointain ; la deuxième<br />

après la cadence, où il apparaît enfin clairement dans la<br />

tonalité principale de sol majeur, en canon entre le piano<br />

et les clarinettes, avant l’envolée Presto finale. Comme le<br />

souligne <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>, tout le finale déploie “une musique<br />

pleine d’énergie vitale, joyeuse, puissante, dynamique,<br />

qui demande une immense palette sonore. Beethoven avait<br />

traversé une grave crise après avoir réalisé la gravité de<br />

sa surdité, il comprenait donc mieux que la plupart des<br />

gens ce qu’est la souffrance. Mais il avait la capacité de<br />

transformer la tragédie en beauté, voire en triomphe, ce<br />

qui n’était pas le moindre aspect de son génie.”<br />

Richard Wigmore<br />

7<br />

INGRID JACOBY<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>, dont le New York Times a vanté “l’articulation<br />

claire … le phrasé éloquent … [et] l’expressivité”, a<br />

conquis le public par son jeu poétique et figure parmi<br />

les pianistes les plus admirées de sa génération.<br />

Elle commence son apprentissage du piano avec<br />

Larisa Gorodecka, elle-même une élève d’Heinrich<br />

Neuhaus. À seize ans, elle obtient son diplôme du<br />

Conservatoire de Saint-Louis (États-Unis) avec félicitations<br />

du jury. Elle remporte ensuite des concours, le National<br />

Baldwin Piano Competition, le Concert <strong>Artists</strong> Guild<br />

<strong>International</strong> Piano Competition, et des prix, le Steinway<br />

Hall <strong>Artists</strong> Prize et le Lifetime Achievement Award, l’une<br />

des plus hautes distinctions décernées par la Société<br />

américaine des Arts et des Lettres.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> donne des concerts dans le monde<br />

entier. Elle s’est produite avec des orchestres de premier<br />

plan sous la direction de chefs comme Sir Charles<br />

Mackerras, Leonard Slatkin, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Walter<br />

Susskind et Yehudi Menuhin. On a pu en outre l’entendre<br />

dans des festivals internationaux, notamment à Aldeburgh,<br />

Aspen, Tuscan Sun et Salzbourg, où elle a interprété des<br />

œuvres de Mozart au Mozarteum.<br />

Sa discographie couvre un répertoire vaste et fascinant.<br />

On y trouve, entre autres, le premier enregistrement mondial<br />

de pièces pour piano de Korngold, des pages de Gershwin<br />

et Bernstein avec l’Orchestre national de Russie, ainsi qu’un<br />

disque des concertos pour piano de Chostakovich et de<br />

Galina Oustvolskaïa, avec le Royal Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

dirigé par Sir Charles Mackerras, auquel l’American Record<br />

Guide a attribué la plus haute distinction.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> est issue d’une famille aux profondes<br />

racines musicales. Elle descend directement du prince<br />

Louis-Ferdinand de Prusse (1772–1806), pianiste et

compositeur auquel Beethoven dédia son Troisième<br />

Concerto pour piano. Louis-Ferdinand était lui-même le<br />

neveu du roi de Prusse Frédéric II, l’auteur du fameux<br />

thème utilisé par J.-S. Bach dans son Offrande musicale.<br />

Traductions : Daniel Fesquet<br />

INGRID JACOBY SPIELT DIE<br />

KLAVIERKONZERTE NR. 2 UND 4<br />

VON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN<br />

Zu Beginn des Jahres 1801 offerierte Ludwig van<br />

Beethoven dem Leipziger Verleger Hoffmeister sein<br />

Klavierkonzert B-dur zu dem äußerst günstigen Preis von<br />

zehn Dukaten, “weil ich’s nicht für eins von meinen besten<br />

ausgebe”. Auf uns wirkt das Konzert wie ein jugendlicher<br />

Charmeur, der vom Geiste Haydns und Mozarts erfüllt ist,<br />

zugleich aber vor originellen Einfällen strotzt und im<br />

Schlussrondo von Beethovens ureigenstem Humor<br />

überfließt. “Ein unterschätztes, köstliches Werk voller<br />

Leben”, lautet <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>s Urteil. Beethoven wird es<br />

1801 indessen gewiss für altmodisch gehalten haben, was<br />

nicht weiter überrascht, da er es bereits 1788 in Angriff<br />

genommen hatte. Die erste Fassung war im Winter<br />

1794/95 fertig und nach der öffentlichen Uraufführung<br />

1795 revidiert worden. Erwartungsgemäß brachte<br />

Beethoven den Klavierpart erst unmittelbar vor der<br />

Publikation zu Papier. Bis dahin hatte er das 1801 als<br />

“Nr. 2” veröffentlichte Konzert immer nur auswendig<br />

gespielt, womit er sicher sein konnte, dass es ihm<br />

niemand “stehlen” würde.<br />

Am Anfang des Konzerts, mit seinem schroffen Appell<br />

und der inständigen Antwort, die sich anschließt, hören wir<br />

die fesselnde Abwandlung eines Eröffnungszuges, den<br />

Mozart gern verwandte. Im weiteren Verlauf jedoch, wo<br />

Mozart ein neues Thema einzuführen pflegte, stürzt sich<br />

Beethoven in die entlegene Tonart Des, um die “inständige<br />

Antwort” des Hauptgedankens weiterzuentwickeln – ein<br />

frühes Exempel seiner weitgespannten Tonartenplanung.<br />

“Er lernt hier von Mozart,” sagt <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>, “und doch<br />

ist der Satz reinster Beethoven: das Empfinden ist<br />

moderner, die Texturen des Klaviers sind viel dichter und<br />

8<br />

brillanter. Und die riesige Kadenz, die er erst 1809<br />

komponierte, ist alles andere als mozartisch. Man findet<br />

darin sogar Elemente der späten Sonaten: den fugierten<br />

Anfang, die Verwendung der extremen Klavierregister und<br />

die Art der Themenentwicklung.”<br />

Das edle, irgendwo zwischen Arie und Kirchenlied<br />

angesiedelte Thema des Es-dur-Adagios zeigt jene<br />

exaltierte Einfachheit, die für die langsamen Sätze des<br />

frühen Beethoven typisch ist. Nicht minder typisch ist, dass<br />

Beethoven diese Melodie anschließend mit einem immer<br />

üppigerem Figurenwerk verziert – wie eine Opernsängerin,<br />

die eine langsame Kantilene ausschmückt. Dabei können<br />

wir sicher sein, dass er diese Verzierungen bei jeder<br />

Aufführung des Konzerts anders gestaltete. Dazu <strong>Jacoby</strong>:<br />

“Mit seinen reichen Texturen und Vorhalten ist dieses<br />

Adagio ein typischer langsamer Satz des jungen Beethoven.<br />

Am Ende haben wir dann ein erstaunliches, äußerst<br />

gefühlsbetontes Rezitativ, das con gran espressione gespielt<br />

und dessen Resonanz durch das Haltepedal verstärkt<br />

werden soll. Hier erreicht Beethoven deutlicher als sonst<br />

[in diesem Werk] seine eigene Klangwelt.”<br />

Mozart beschloss seine B-dur-Konzerte gern mit<br />

einem Jagdrondo im Sechsachteltakt. Beethovens folgt<br />

diesem Beispiel, wenngleich er es auf seine eigene,<br />

subversive Weise tut, indem er das eingängige Hauptthema<br />

mit ausgefallenen Akzenten würzt. Weitere rhythmische<br />

Verschiebungen enthalten die zentrale Episoden, wo das<br />

Thema mit boogie-artigen Synkopen versehen wird. “Hier<br />

zeigt sich Beethovens Humor von seiner wildesten Seite,”<br />

sagt <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>. “Das Thema an sich ist simpel, doch<br />

im Mittelteil hat er seinen Spaß daran, uns mit all seinen<br />

Synkopen und harmonischen Dissonanzen eine Nase zu<br />

drehen.” Den wohl geistreichsten Streich führt er in der<br />

Coda, wo das Klavier nonchalant nach G-dur gleitet, um<br />

eine gebändigte Version des Rondo-Themas zu spielen,<br />

9<br />

bevor das Orchester lautstark mit der originalen,<br />

widerspenstigen Melodie dreinfährt.<br />

Die sogenannte “mittlere” Schaffensperiode Beethovens<br />

– sie entspricht ungefähr der Dekade seit 1803 – assoziiert<br />

man vor allem mit den heldenhaften Kämpfen des<br />

Künstlers. Doch das Bild vom stirnrunzelnden Titanen, der<br />

da seine gewaltigen, dynamischen Strukturen schmiedet,<br />

ist weit von einem kompletten Portrait entfernt. Nicht<br />

weniger kennzeichnend sind jene Werke, in denen<br />

sich Beethovens große Gedankenwelt mit einer neuen<br />

lyrischen Breite und Ruhe verbindet: die “Pastorale”, das<br />

Violinkonzert und das vierte Klavierkonzert, die auf ihre<br />

Weise ebenso revolutionär sind wie die ethisch gespannten<br />

Kämpfe der “Eroica” und der fünften Sinfonie.<br />

Zwei Jahre nach den ersten flüchtigen Skizzen begann<br />

Beethoven 1806 mit der eigentlichen Arbeit an dem<br />

G-dur-Konzert – zur selben Zeit also, da auch die fünfte<br />

Sinfonie im Entstehen begriffen war, und es ist gewiss<br />

kein Zufall, dass die Kopfsätze beider Werke dasselbe<br />

Viertonmotiv aus zwei drastisch unterschiedenen<br />

Perspektiven betrachten. <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>: “In der Sinfonie<br />

komprimiert und kontrahiert Beethoven. Im Konzert tut er<br />

das Gegenteil, wenn er das Eingangsmotiv mit heiterer<br />

Gelassenheit expandiert.” Der Komponist selbst hob das<br />

Werk im Rahmen des riesenhaften Konzertabends aus der<br />

Taufe, den er am 22. Dezember 1808 zu seinem eigenen<br />

Besten im Theater an der Wien veranstaltete. Uraufgeführt<br />

wurden damals unter anderem auch die Pastorale und<br />

die fünfte Sinfonie, Teile der C-dur-Messe und die<br />

Chorfantasie. Es gibt nur wenige Berichte von diesem<br />

Ereignis. Allerdings registrierte der Komponist Johann<br />

Friedrich Reichardt, der in dem eiskalten Theater anwesend<br />

war, “ein neues Pianoforte-Konzert von ungeheurer<br />

Schwierigkeit, welches Beethoven zum Erstaunen brav,<br />

in den allerschnellsten Tempi aufführte.”

Das Konzert beginnt auf beispiellose Weise mit dem<br />

Solisten, der im üppigen, volltönenden Klang seines<br />

mittleren Registers ein Thema von erlesener Zartheit<br />

exponiert: “Die scheinbare Einfachheit dieses poetischen<br />

Anfangs täuscht über die wirklichen Schwierigkeiten<br />

hinweg,” sagt <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>. “Man braucht dazu eine<br />

vollkommene Klangkontrolle, um die Akkorde in eine<br />

genaue Balance zu bringen. Ich muss dabei an Artur<br />

Schnabels Wort denken, wonach große Musik größer ist,<br />

als man sie je spielen kann.”<br />

Trotz einiger Momente virtuoser Brillanz, auf die auch<br />

der oben zitierte Rezensent hinwies, beherrscht ein Ton<br />

der leisen Vertraulichkeit den ersten Satz. Immer wieder<br />

lenkt das Klavier auf ruhige Weise die energischen<br />

Anläufe des Orchesters ab, indem sich die angesteuerten<br />

Höhepunkte in lyrische Meditationen auflösen. So machen<br />

wir uns beispielsweise bei dem langen Triller am Ende<br />

der Exposition auf ein rauschendes Orchestertutti gefasst.<br />

Doch Beethoven enttäuscht die Erwartungen mit einer<br />

bewegenden Passage, in der der Solist über das<br />

kadenzierende Thema nachdenkt, das man erstmals in<br />

der Orchestereinleitung hatte hören können.<br />

Auch in dem theatralisch-szenisch konzipierten<br />

Andante con moto spielt das Klavier die Rolle des sanften<br />

Friedensstifters. Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts verglich Adolf<br />

Bernhard Marx in seiner Beethoven-Biographie diesen<br />

Satz denn auch mit dem Moment, da Orpheus die Furien<br />

besänftigt. Man kann hier freilich auch den Zusammenprall<br />

zweier musikalischer Welten vernehmen: Die barocke<br />

Strenge der schroff punktierten Unisono-Streicher,<br />

deren erste Phrase aus einer tragischen scena Händels<br />

herkommen könnte, trifft in den zart harmonisierten<br />

Antworten des Klaviers auf romantisches Pathos.<br />

“Fast bis zum Ende verlangt Beethoven una corda, also<br />

das Verschiebungs- oder Dämpferpedal”, erläutert <strong>Ingrid</strong><br />

10<br />

<strong>Jacoby</strong>, “womit die Musik auf wundersame Weise<br />

verschleiert wird.” Nach und nach wird das schroffe<br />

Orchester durch die immer eloquenteren Bitten des<br />

Klaviers bezwungen, das schließlich in einer<br />

leidenschaftlichen, kadenzartigen Klimax mit einem<br />

langen fortissimo-Triller seinen Vorrang behauptet, ehe<br />

die punktierten Rhythmen zu einem geisterhaften<br />

Flüstern im Bass herabsinken.<br />

Das Andante verharrt fast durchweg in der Tonart<br />

e-moll. Das leise und attacca einsetzende Rondo führt<br />

dann über einige C-dur-Takte wieder nach G-dur zurück:<br />

Den geistreichen Kunstgriff, abseits der Grundtonart zu<br />

beginnen, hatte Beethoven von Joseph Haydn gelernt.<br />

Trotz aller Pracht und Verspieltheit ist das Finale im Kern<br />

ebenso ruhig und gesanglich wie der Kopfsatz: Beispielhaft<br />

sind hier das zweite Thema, das der Solist dolce über<br />

einem tiefen Orgelpunkt in zwei weit gespannten<br />

kontrapunktischen Linien ankündigt, sowie die schöne<br />

Transformation des Hauptthemas, das gegen Ende<br />

des Werkes zunächst von den geteilten Bratschen im<br />

entlegenen Es-dur gespielt wird, um nach der Kadenz<br />

kanonisch von Klavier und Klarinetten im unzweideutigen<br />

G-dur auf die galoppierende Presto-Coda zuzusteuern.<br />

Für <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> enthält der ganze Schluss-Satz eine<br />

“lebensbejahende, frohsinnige und kraftvolle, energisch<br />

angetriebene Musik, die ein gewaltiges Klangspektrum<br />

verlangt. Beethoven hatte die Krise seiner Ertaubung<br />

überwunden – er wusste besser als andere Menschen,<br />

was Leiden bedeutete. Es dürfte ein Aspekt seines Genies<br />

sein, dass er fähig war, die Tragödie in Schönheit und<br />

sogar in Triumph zu verwandeln.”<br />

Richard Wigmore<br />

INGRID JACOBY<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>, deren “klare Artikulation … unvergleichliche<br />

Phrasierung … [und] Expressivität” die New York Times lobte,<br />

hat sich als eine der poetischsten und meistbewunderten<br />

Pianisten ihrer Generation einen Namen gemacht.<br />

Ihre pianistische Ausbildung begann <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> bei<br />

Larisa Gorodecka, einer Schülerin von Heinrich Neuhaus.<br />

Als Sechzehnjährige beschloss sie ihr Studium am<br />

Konservatorium von St. Louis. Anschließend entschied sie<br />

den nationalen Baldwin-Wettbewerb und den <strong>International</strong>en<br />

Wettbewerb der Concert <strong>Artists</strong> Guild für sich. Außerdem<br />

wurde sie mit dem Künstlerpreis der Steinway Hall<br />

ausgezeichnet. Die amerikanische Gesellschaft für<br />

Kunst und Literatur verlieht ihr eine ihrer höchsten<br />

Anerkennungen, den Lifetime Achievement Award.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> hat in aller Welt konzertiert und mit<br />

großen Orchestern unter Dirigenten wie Sir Charles<br />

Mackerras, Leonard Slatkin, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Walter<br />

Susskind und Lord Yehudi Menuhin musiziert. Aldeburgh<br />

und Aspen gehören ebenso zu ihren Festspiel-Adressen<br />

wie das Tuscan Sun Festival und das Salzburger<br />

Mozarteum, wo <strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> Werke von Wolfgang<br />

Amadeus Mozart aufgeführt hat.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong>s Diskographie umfasst ein großes,<br />

spannendes Repertoire. Dazu gehören die Solowerke von<br />

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (Weltpremiere-Aufnahme), Musik<br />

von George Gershwin und Leonard Bernstein mit dem<br />

Russischen Nationalorchester, sowie eine Aufnahme der<br />

Klavierkonzerte von Dmitri Schostakowitsch und Galina<br />

Ustwolskaja mit dem Royal Philharmonic Orchestra unter<br />

Sir Charles Mackerras, die im American Record Guide die<br />

höchsten Empfehlungen erhielt.<br />

<strong>Ingrid</strong> <strong>Jacoby</strong> entstammt einer Familie, in der die<br />

Musik tief verwurzelt ist. Sie ist eine direkte Nachfahrin<br />

11<br />

des Pianisten und Komponisten Prinz Louis Ferdinand<br />

(1772–1806), dem Beethoven sein drittes Klavierkonzert<br />

widmete. Der preußische Prinz war ein Neffe Friedrichs<br />

des Großen, der das berühmte Thema erfand, über das<br />

Johann Sebastian Bach sein erhabenes Musikalisches<br />

Opfer komponierte.<br />

Übersetzungen: Eckhardt van den Hoogen<br />

For a free promotional CD sampler including<br />

highlights from the ICA Classics CD catalogue,<br />

please email info@icaclassics.com.

For ICA Classics<br />

Executive Producer/Head of Audio: John Pattrick<br />

Music Rights Executive: Aurélie Baujean<br />

Head of DVD: Louise Waller-Smith<br />

Executive Consultant: Stephen Wright<br />

Recording Supervision/Sound Engineering: Lech Dudzik,<br />

Gabriela Blicharz<br />

Mastering: Gabriela Blicharz<br />

ICA Classics acknowledges the assistance of Katy Cork<br />

(<strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong>)<br />

Also available on CD and digital download:<br />

Financial support for this recording has been<br />

provided in loving memory of Marian V Parfet<br />

and Genevieve U Gilmore<br />

Introductory note, biography & translations<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Booklet editing: WLP Ltd<br />

Art direction: Georgina Curtis for WLP Ltd<br />

2012 Nota Bene Capolavori Ltd, under licence<br />

to <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Stereo DDD<br />

ICAC 5000<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concertos Nos.1 & 3<br />

New Philharmonia Orchestra · Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5004<br />

Haydn: Piano Sonata No.62<br />

Weber: Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Schumann · Chopin · Debussy<br />

Sviatoslav Richter<br />

Diapason d’or<br />

ICAC 5008<br />

Liszt: Rhapsodie espagnole<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.2<br />

CPE Bach · Couperin · Scarlatti<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

WARNING:<br />

All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring,<br />

lending, public performance and broadcasting prohibited.<br />

Licences for public performance or broadcasting may be obtained<br />

from Phonographic Performance Ltd., 1 Upper James Street,<br />

London W1F 9DE. In the United States of America unauthorised<br />

reproduction of this recording is prohibited by Federal law and<br />

subject to criminal prosecution.<br />

Made in Austria<br />

ICAC 5003<br />

Brahms: Piano Concerto No.2<br />

Chopin · Falla<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Christoph von Dohnányi · Arthur Rubinstein<br />

Gramophone Editor’s Choice<br />

ICAC 5020<br />

Rachmaninov: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini<br />

Prokofiev: Piano Sonata No.7<br />

Stravinsky: Three Scenes from Petrushka<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Zdeněk Mácal<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

ICAC 5023<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.3<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.6 ‘Pathétique’<br />

Novaya Rossiya State Symphony Orchestra<br />

Yuri Bashmet<br />

12<br />

13

ICAC 5045<br />

Chopin: Piano Concerto No.1<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.4<br />

Otto Klemperer · Christoph von Dohnányi<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Claudio Arrau<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzicato Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5048<br />

Brahms: Piano Concerto No.1<br />

Chopin · Liszt · Schumann · Albéniz<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Rudolf Kempe<br />

Julius Katchen<br />

ICAC 5077<br />

Brahms: Piano Concerto No.2<br />

Debussy · Prokofiev<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Mario Rossi<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5079<br />

Grieg · Liszt: Piano Concertos<br />

Lully · Scarlatti<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Georges Tzipine · André Cluytens<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5055<br />

Schubert: Impromptu in B flat<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 6 & 29<br />

Wilhelm Backhaus<br />

ICAC 5062<br />

Schumann: Piano Concerto<br />

Beethoven: Eroica Variations · Piano Sonata No.30<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Joseph Keilberth<br />

Annie Fischer<br />

ICAC 5084<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Bagatelles op.126 Nos. 1, 4 & 6<br />

Piano Sonata No.29 ‘Hammerklavier’<br />

Sviatoslav Richter<br />

ICAC 5085<br />

Chopin: Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2<br />

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Christopher Adey<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Richard Hickox<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

14<br />

15