to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

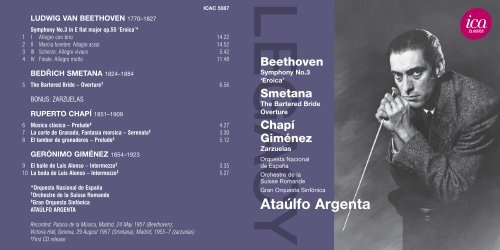

ICAC 5087<br />

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770–1827<br />

Symphony No.3 in E flat major op.55 ‘Eroica’*<br />

1 I Allegro con brio 14.22<br />

2 II Marcia funebre: Adagio assai 14.52<br />

3 III Scherzo: Allegro vivace 5.42<br />

4 IV Finale: Allegro mol<strong>to</strong> 11.48<br />

BEDŘICH SMETANA 1824–1884<br />

5 The Bartered Bride – Overture † 6.56<br />

BONUS: ZARZUELAS<br />

RUPERTO CHAPÍ 1851–1909<br />

6 Música clásica – Prelude ‡ 4.27<br />

7 La corte de Granada, Fantasía morsica – Serenata ‡ 3.30<br />

8 El tambor de granaderos – Prelude ‡ 5.12<br />

GERÓNIMO GIMÉNEZ 1854–1923<br />

9 El baile de Luis Alonso – Intermezzo ‡ 3.35<br />

10 La boda de Luis Alonso – Intermezzo ‡ 5.27<br />

*Orquesta Nacional de España<br />

† Orchestre de la Suisse Romande<br />

‡ Gran Orquesta Sinfónica<br />

ATAÚLFO ARGENTA<br />

Beethoven<br />

Symphony No.3<br />

‘Eroica’<br />

Smetana<br />

The Bartered Bride<br />

Overture<br />

Chapí<br />

Giménez<br />

Zarzuelas<br />

Orquesta Nacional<br />

de España<br />

Orchestre de la<br />

Suisse Romande<br />

Gran Orquesta Sinfónica<br />

Ataúlfo Argenta<br />

Recorded: Palacia de la Música, Madrid, 24 May 1957 (Beethoven);<br />

Vic<strong>to</strong>ria Hall, Geneva, 29 August 1957 (Smetana); Madrid, 1955–7 (zarzuelas)<br />

‡ First CD release

ARGENTA CONDUCTS BEETHOVEN,<br />

SMETANA AND ZARZUELAS<br />

Mozart. Schubert. Gershwin. Ferrier. Lipatti. Cantelli. Those<br />

are but a handful of lionised musicians whose lives were<br />

cut short by illness or disaster, thus depriving the world of<br />

accomplishments that can hardly be imagined. Another artist<br />

many believe qualifies for this firmament is Ataúlfo Argenta,<br />

dubbed ‘Spain’s No.1 conduc<strong>to</strong>r’ by Time magazine in 1954.<br />

Argenta came <strong>to</strong> international renown through acclaimed<br />

Decca recordings (made from 1953 <strong>to</strong> 1957) and EMI<br />

recordings of beloved classical works and zarzuelas with<br />

English, French, Spanish and Swiss orchestras. His American<br />

debut was on the horizon, and he was scheduled <strong>to</strong> record<br />

the four Brahms symphonies with the Vienna Philharmonic<br />

for Decca in spring 1958. But on a cold night in January of<br />

that year, while waiting for the studio in his Madrid home<br />

<strong>to</strong> warm up, the forty-four-year-old Argenta switched on<br />

his car mo<strong>to</strong>r and heater without opening the garage door.<br />

A student who was with him ‘was found unconscious and<br />

Argenta died of carbon monoxide poisoning,’ wrote Alan<br />

Sanders in a biography for the box set of the conduc<strong>to</strong>r’s<br />

complete Decca discography. ‘On the day of his funeral<br />

crowds lined the streets through which the cortège passed,<br />

and his death was mourned [throughout Spain].’<br />

The dynamism and insight Argenta shared with<br />

musicians and audiences can be heard on these<br />

recordings, but they aren’t the only evidence of his<br />

charisma as interpreter of an array of music. From<br />

performances taped in concert, one hears a master<br />

communica<strong>to</strong>r who takes nothing for granted and delves<br />

deeply in<strong>to</strong> the messages the composer set down. Among<br />

those performances are the selections on the present disc,<br />

which find Argenta as vibrant in well-known works by<br />

Beethoven and Smetana as he is in orchestral excerpts<br />

2<br />

from zarzuelas, those popular Spanish theatrical blends of<br />

operatic and folk elements.<br />

Born in the northern region of Cantabria in 1913, Argenta<br />

studied voice, violin and piano, advancing so quickly on the<br />

last instrument that he thought a career as a concert pianist<br />

might be possible. After his debut as a conduc<strong>to</strong>r in 1934, he<br />

juggled these two facets of music-making until conducting<br />

dominated his professional life. Concerts with the Spanish<br />

National Orchestra – and recordings, including the first<br />

commercial release of Joaquín Rodrigo’s Concier<strong>to</strong> de<br />

Aranjuez, with guitarist Regino Sáinz de la Maza, the work’s<br />

dedicatee, as soloist – led <strong>to</strong> appearances with ensembles<br />

outside of Spain. Argenta appeared as guest with the London<br />

Symphony, London Philharmonic, Paris Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire<br />

Orchestra and L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, whose<br />

music direc<strong>to</strong>r, Ernest Ansermet, so admired him that he<br />

began grooming him <strong>to</strong> be his successor.<br />

In addition <strong>to</strong> the Decca recordings, a prime selection<br />

of Argenta performances are preserved on a collection in<br />

EMI’s ‘Great Conduc<strong>to</strong>rs of the 20th Century’ series, which<br />

includes a fervent Liszt (A Faust Symphony), ravishing<br />

Ravel (Alborada del gracioso), broad and noble Schubert<br />

(Ninth Symphony) and sizzling Falla (El amor brujo). These<br />

recordings were made with the Paris Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire<br />

Orchestra and the so-called Orchestre des Cen<strong>to</strong> Soli (a<br />

melding of Parisian musicians), which confirms the high<br />

esteem in which Argenta was held in the French capital.<br />

The Geneva-based Suisse Romande is one of the<br />

orchestras with which Argenta collaborates on the present<br />

recording in a rollicking account of the overture <strong>to</strong><br />

Smetana’s The Bartered Bride from August 1957, five<br />

months before his death. After the explosive opening,<br />

Argenta keeps a tight reign on the chattering string lines,<br />

maintaining utmost transparency of texture and articulation.<br />

The activity is propulsive, with a tremendous crescendo<br />

leading in<strong>to</strong> the jubilant main theme, which is lovingly<br />

phrased. Argenta makes sure fugal entrances hit the<br />

bull’s eye, even as he stresses the vivacious folksiness<br />

with which Smetana introduces his opera’s exuberant<br />

personality. The performance takes a slight breath near<br />

the end before dashing <strong>to</strong> the finish line.<br />

Like Smetana, Beethoven doesn’t figure on Argenta’s<br />

recorded reper<strong>to</strong>ire list, which makes the performance<br />

of the ‘Eroica’ Symphony here with the Spanish National<br />

Orchestra from May 1957 such an important document.<br />

While it’s apparent that this orchestra is not on the level of<br />

other ensembles he led, especially the London Symphony<br />

(which Sanders considers the first ‘truly virtuosic body’<br />

he conducted), the performance presents Argenta as a<br />

commanding and disciplined Beethoven interpreter. He<br />

shapes a propulsive first movement, without shortchanging<br />

elasticity, and achieves exceptional clarity. The second<br />

movement builds <strong>to</strong> majestic climaxes, the Scherzo is lithe<br />

and swaggering (thanks partly <strong>to</strong> vivacious horns) and the<br />

finale possesses exceptional kinetic intensity.<br />

The zarzuela excerpts, performed with Madrid’s Gran<br />

Orquesta Sinfónica from 1955 <strong>to</strong> 1957, reveal Argenta’s<br />

special <strong>to</strong>uch in music of lighter character. A quote from<br />

the second movement of Beethoven’s ‘Pas<strong>to</strong>ral’ Symphony<br />

and bits of Mendelssohn make endearing appearances in<br />

the first zarzuela selection, the Prelude <strong>to</strong> Ruper<strong>to</strong> Chapí’s<br />

Música clásica. Argenta also elicits bountiful charm,<br />

humour and Spanish flair from the remaining pieces by<br />

Chapí and Gerónimo Giménez. Hearing the conduc<strong>to</strong>r<br />

apply such authority <strong>to</strong> these delectable morsels, it’s no<br />

surprise that he recorded fifty complete zarzuelas. But we<br />

can only wonder what more this ‘great conduc<strong>to</strong>r of the<br />

20th century’ would have contributed if he hadn’t perished<br />

early in such a bizarre accident.<br />

Donald Rosenberg<br />

3<br />

ARGENTA DIRIGE BEETHOVEN,<br />

SMETANA ET DES ZARZUELAS<br />

Mozart. Schubert. Gershwin. Ferrier. Lipati. Cantelli. Ce ne<br />

sont là que quelques-uns parmi les nombreux musiciens<br />

adulés dont la vie fut coupée net par la maladie ou une<br />

catastrophe, privant ainsi le monde de merveilles que l’on<br />

a bien de la peine à imaginer. Un autre artiste que<br />

beaucoup considèrent comme digne de figurer à ce<br />

firmament est Ataúlfo Argenta, surnommé “le meilleur chef<br />

d’orchestre de l’Espagne” par le Time Magazine en 1954.<br />

Argenta acquit une renommée internationale grâce à des<br />

enregistrements Decca (réalisés de 1953 à 1957) et de<br />

classiques favoris et de zarzuelas EMI avec des orchestres<br />

anglais, français, espagnols et suisses. Il allait faire ses<br />

débuts en Amérique et devait enregistrer les quatre<br />

symphonies de Brahms avec le Philharmonique de Vienne<br />

pour Decca au printemps 1958 lorsqu’une froide nuit de<br />

janvier de cette année-là, à Madrid, en attendant que son<br />

studio se réchauffe, il alluma le moteur et le chauffage de<br />

sa voiture sans ouvrir la porte du garage. Un étudiant qui<br />

se trouvait avec lui fut “retrouvé inconscient, et Argenta<br />

[qui n’avait que quarante-quatre ans] décéda d’un<br />

empoisonnement au monoxyde de carbone”, écrivit Alan<br />

Sanders dans une biographie destinée au coffret de la<br />

discographie complète du chef d’orchestre chez Decca.<br />

“Le jour de ses funérailles, la foule se pressait le long des<br />

rues par lesquelles passait le cortège funèbre, et sa mort<br />

fut pleurée [à travers <strong>to</strong>ut l’Espagne].”<br />

Le dynamisme et l’intelligence d’Argenta, qui<br />

rejaillissaient sur les musiciens et le public,<br />

transparaissent dans ces enregistrements, mais ne<br />

sont pas les seules manifestations du charisme de cet<br />

interprète d’œuvres musicales fort diverses. Dans ses<br />

concerts enregistrés en public, on entend à l’ouvrage un

maître de la communication qui ne prend rien pour acquis<br />

et explore à fond le message du compositeur. Parmi ces<br />

interprétations, celles réunies ici montrent un Argenta<br />

aussi dynamique dans les chefs-d’œuvre bien connus de<br />

Beethoven et de Smetana que dans les extraits orchestraux<br />

de zarzuelas, ces mélanges populaires espagnols<br />

d’éléments folkloriques et d’opéra.<br />

Né en 1913 dans le nord de l’Espagne, en Cantabrie,<br />

Argenta étudia le chant, le violon et le piano, faisant des<br />

progrès si fulgurants au clavier qu’il envisagea une carrière<br />

de pianiste de concert. Après ses débuts au pupitre de<br />

chef d’orchestre, en 1934, il jongla avec ces deux facettes<br />

de son talent, jusqu’à ce que la direction d’orchestre<br />

finisse par dominer sa vie professionnelle. Des concerts<br />

avec l’Orchestre national Espagnol, ainsi que des<br />

enregistrements, dont le premier enregistrement du<br />

Concier<strong>to</strong> de Aranjuez de Joaquín Rodrigo, avec en soliste<br />

le guitariste Regino Sáinz de la Maza, le dédicataire de<br />

l’œuvre, l’amenèrent à se produire en-dehors de l’Espagne<br />

à la tête de divers ensembles. Il fut ainsi invité par le<br />

London Symphony, le London Philharmonic, l’Orchestre du<br />

Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire de Paris et l’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande,<br />

dont le directeur musical, Ernest Anseremet, l’admirait<br />

tellement qu’il le prépara à prendre sa succession.<br />

En plus des enregistrements Decca, une excellente<br />

sélection d’interprétations d’Argenta est parue chez EMI<br />

dans la série Great Conduc<strong>to</strong>rs of the 20th Century, qui<br />

comprend un Liszt passionné (Faust-Symphonie), un Ravel<br />

enchanteur (Alborada del gracioso), un Schubert large et<br />

noble (Neuvième Symphonie) et un Falla <strong>to</strong>rride (El amor<br />

brujo). Ces enregistrements furent réalisés avec l’Orchestre<br />

du Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire de Paris et l’Orchestre des Cen<strong>to</strong> Soli (un<br />

ensemble de musiciens parisiens d’horizons divers), ce<br />

qui confirme la haute estime dont jouissait Argenta dans la<br />

capitale française.<br />

L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande basé à Genève<br />

est la formation que dirige Argenta dans l’interprétation<br />

joyeuse de l’ouverture de La Fiancée vendue de Smetana,<br />

captée en août 1957, cinq mois avant la mort du chef<br />

d’orchestre. Après un début explosif, Argenta tient<br />

fermement les lignes mélodiques bavardes des cordes,<br />

maintenant une parfaite transparence dans la texture et<br />

l’articulation. Il propulse l’action vers l’avant avec un<br />

formidable crescendo menant au thème principal radieux,<br />

phrasé avec amour. Argenta s’assure que les entrées<br />

fuguées sont parfaitement exactes, même lorsqu’il met en<br />

évidence l’esprit populaire et enjoué par lequel Smetana<br />

ouvre son opéra exubérant. Peu avant la fin, il reprend<br />

haleine, avant de se précipiter vers les notes finales.<br />

Tout comme Smetana, Beethoven ne figure pas sur<br />

la liste des œuvres enregistrées par Argenta, ce qui<br />

donne une importance <strong>to</strong>ute particulière à son Eroica<br />

avec l’Orchestre national Espagnol captée en mai 1957.<br />

S’il apparaît clairement que cet orchestre n’est pas au<br />

même niveau que d’autres ensembles qu’il avait dirigés,<br />

principalement le London Symphony (que Sanders<br />

considère comme le premier “ensemble réellement<br />

virtuose” qu’Argenta ait dirigé), l’enregistrement nous<br />

montre un interprète de Beethoven à la fois discipliné et<br />

imposant. Argenta façonne un premier mouvement vif, sans<br />

négliger la souplesse, et obtient une clarté exceptionnelle.<br />

Le deuxième mouvement s’élève à des sommets<br />

majestueux, le Scherzo est agile et fanfaron (en partie<br />

grâce aux cors pleins de vivacité) et le Finale développe<br />

une intensité cinétique exceptionnelle.<br />

Les extraits de zarzuelas, interprétés avec le Gran<br />

Orquesta Sinfónica de Madrid de 1955 à 1957, révèlent<br />

la <strong>to</strong>uche particulière qu’Argenta apporte à la musique<br />

plus légère. Une citation du deuxième mouvement de la<br />

Symphonie “Pas<strong>to</strong>rale” de Beethoven et des emprunts à<br />

Mendelssohn font des apparitions <strong>to</strong>uchantes dans le<br />

premier extrait de zarzuela, le Prélude de la Música<br />

clásica de Ruper<strong>to</strong> Chapí. Argenta met également en<br />

valeur le charme généreux, l’humour et l’esprit espagnol<br />

des autres pièces de Chapí et de Gerónimo Giménez.<br />

Vu la maestria avec laquelle il traite ces petits bijoux, on<br />

n’est guère surpris qu’il ait enregistré cinquante zarzuelas<br />

intégralement. Et l’on ne peut que se demander ce que ce<br />

“grand chef d’orchestre du XX e siècle” aurait encore<br />

apporté au monde s’il n’avait péri prématurément dans<br />

un accident aussi absurde.<br />

Donald Rosenberg<br />

Traduction : Sophie Liwszyc<br />

4 5<br />

ARGENTA DIRIGIERT BEETHOVEN,<br />

SMETANA UND ZARZUELAS<br />

Mozart. Schubert. Gershwin. Ferrier. Lipatti. Cantelli. Dies<br />

sind nur eine Handvoll von vergötterten Musikern, deren<br />

Leben durch Krankheit oder Katastrophe vorzeitig<br />

abgeschnitten wurde, was der Welt kaum vorstellbare<br />

Leistungen vorenthalten hatte. Ein weiterer Künstler, von<br />

dem viele glauben, dass auch er in dieses Firmament<br />

gehört, ist Ataúlfo Argenta, den die Zeitschrift Time<br />

1954 den “Ersten Dirigenten Spaniens” nannte. Argenta<br />

errang sich durch hochgepriesene Aufnahmen für Decca<br />

(1953–1957) und EMI-Einspielungen von beliebten<br />

klassischen Werken und Zarzuelas mit englischen,<br />

französischen, spanischen und Schweizer Orchestern<br />

internationales Ansehen. Sein amerikanisches Debüt stand<br />

kurz bevor, und im Frühjahr 1958 sollte er mit den Wiener<br />

Philharmonikern die vier Brahms-Sinfonien für Decca<br />

einspielen, als der 44-jährige Dirigent in einer kalten Nacht<br />

in diesem Jahr in seinem Au<strong>to</strong> darauf wartete, dass sich das<br />

Studio in seiner Wohnung in Madrid aufwärmte, und den<br />

Mo<strong>to</strong>r für die Heizung anließ, ohne das Garagen<strong>to</strong>r zu<br />

öffnen. Ein Student, der mit ihm im Au<strong>to</strong> war, “wurde<br />

bewusstlos gefunden, und Argenta starb an<br />

Kohlenmonoxidvergiftung”, schrieb Alan Sanders in seiner<br />

Biografie für ein Boxset der gesamten Decca-Diskografie<br />

des Dirigenten. “Am Tag seines Begräbnisses säumten<br />

große Scharen die Straßen, durch die der Leichenzug führte,<br />

und sein Tod wurde [in ganz Spanien] betrauert.”<br />

Die Dynamik und Einsicht, die Argenta mit Musikern<br />

und Publikum teilte, lässt sich auf diesen Einspielungen<br />

hören, aber sie sind nicht die einzigen Zeugnisse für sein<br />

Charisma als Interpret einer großen Vielfalt von Musik. In<br />

Konzertmitschnitten hört man einen meisterlichen<br />

Kommunika<strong>to</strong>r, der nichts für selbstverständlich hält und

sich in die Botschaften vertieft, die der Komponist<br />

vermittelt. Die Auswahl auf der vorliegenden CD<br />

stammt aus diesen Aufführungen, in denen Argenta in<br />

wohlbekannten Werken von Beethoven und Smetana<br />

genauso dynamisch ist wie in Orchesterauszügen aus<br />

Zarzuelas, der populären spanischen Mischung von<br />

Oper und Volksmusik.<br />

Argenta wurde 1913 im nördlichen Kantabrien geboren<br />

und studierte Gesang, Violine und Klavier. Er machte auf<br />

dem Klavier so schnelle Fortschritte, dass er eine Karriere<br />

als Konzertpianist für möglich hielt. Nach seinem Debüt als<br />

Dirigent 1934 jonglierte er mit diesen beiden Disziplinen,<br />

bis das Dirigieren schließlich die professionelle Oberhand<br />

gewann. Konzerte mit dem Spanischen Nationalorchester –<br />

und Aufnahmen einschließlich der ersten kommerziellen<br />

Aufnahme von Joaquín Rodrigos Concier<strong>to</strong> de Aranjuez, mit<br />

dem Gitarristen und Widmungsträger des Werks Regino<br />

Sáinz de la Maza als Solisten – führte zu Auftritten mit<br />

Ensembles außerhalb Spaniens. Argenta erschien als Gast<br />

mit dem London Symphony, London Philharmonic, Pariser<br />

Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire-Orchester und L’Orchestre de la Suisse<br />

Romande, dessen Musikdirek<strong>to</strong>r Ernest Ansermet ihn so<br />

sehr bewunderte, dass er begann, ihn als seinen<br />

Nachfolger zu präparieren.<br />

Zusätzlich zu den Decca-Einspielungen ist auch<br />

eine erstklassisge Auswahl von Argenta-Aufführungen<br />

in einer Sammlung der EMI-Serie “Große Dirigenten<br />

des 20. Jahrhunderts” erhalten, die einen feurigen Liszt<br />

(Eine Faust-Sinfonie), mitreißenden Ravel (Alborada<br />

del gracioso), ausladend-noblen Schubert (Neunte<br />

Sinfonie) und glühend heißen Falla (El amor brujo)<br />

enthält. Diese Aufnahmen entstanden mit dem Pariser<br />

Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire-Orchester und dem sogenannten Orchestre<br />

des Cen<strong>to</strong> Soli (einer Verschmelzung Pariser Musiker)<br />

und unterstreichen wie hoch Argenta in der französischen<br />

6<br />

Hauptstadt geschätzt wurde.<br />

In der im August 1957, nur fünf Monate vor seinem<br />

Tode eingespielten augelassenen Interpretation der<br />

Ouvertüre zu Smetanas Verkaufter Braut arbeitete Argenta<br />

mit dem in Genf ansässigen Orchestre de la Suisse<br />

Romande. Nach dem explosiven Beginn hält Argenta<br />

die geschwätzigen Streicherlinien fest im Zügel, um<br />

äußerste Transparenz des Satzes und der Artikulation<br />

aufrechtzuerhalten. Er treibt die Handlung stets voran und<br />

ein überwältigendes Crescendo führt in das liebevoll<br />

phrasierte Hauptthema. Argenta stellt sicher, dass<br />

Fugeneinsätze immer ins Schwarze treffen und unterstreicht<br />

gleichzeitig die lebhafte Volkstümlichkeit, mit der Smetana<br />

die überschwängliche Persönlichkeit seiner Oper einführt.<br />

Vor dem Endspurt hält die Aufführung für eine kurze<br />

Verschnaufpause ein.<br />

Wie Smetana fehlt auch Beethoven in Argentas<br />

Aufnahmeliste, was die hier vorliegende Aufführung der<br />

“Eroica” mit dem Spanischen Nationalorchester vom Mai<br />

1957 zu einem so bedeutenden Dokument macht. Obwohl<br />

dieses Orchester offensichtlich nicht ganz auf dem<br />

gleichen Niveau steht wie die anderen Ensembles die er<br />

leitete – besonders das London Symphony Orchestra (das<br />

Sanders als den ersten “wahrhaft virtuosen Musikerkorpus”<br />

bezeichnete, den er leitete) – zeigt die Aufführung Argenta<br />

als kommandierenden und disziplinierten<br />

Beethoven-Interpreten. Er gestaltet einen<br />

vorwärtstreibenden ersten Satz, der trotzdem elastisch<br />

bleibt, und erreicht eine außerordentliche Klarheit. Der<br />

zweite Satz steigert sich in majestätische Höhepunkte, das<br />

Scherzo ist geschmeidig und aufschneiderisch (zum Teil<br />

dank lebhafter Hörner), und das Finale besitzt<br />

außerordentliche kinetische Intensität.<br />

Die Zarzuela-Ausschnitte, die zwischen 1955 und 1957<br />

mit dem Madrider Gran Orquesta Sinfónica aufgeführt<br />

wurden, enthüllen Argentas besonderen Touch in Musik<br />

der leichteren Musik. In der ersten Zarzuela-Auswahl, dem<br />

Vorspiel zu Ruper<strong>to</strong> Chapís Música clásica tauchen ein<br />

Zitat aus dem zweiten Satz von Beethovens “Pas<strong>to</strong>rale”<br />

und und hier und da ein bisschen Mendelssohn auf.<br />

Argenta holt auch aus den übrigen Stücken von Chapí<br />

und Gerónimo Giménez viel Humor und spanisches<br />

Flair heraus. Wenn man hört, wieviel Au<strong>to</strong>rität er diesen<br />

entzückenden Musikhäppchen verleiht, überrascht es nicht,<br />

dass er 50 vollständige Zarzuelas aufnahm. Wir können<br />

aber nur spekulieren, wieviel mehr dieser “große Dirigent<br />

des 20. Jahrhunderts” hätte beitragen können, wenn er<br />

nicht in so frühem Alter in einem solch bizarren<br />

Missgeschick umgekommen wäre.<br />

Donald Rosenberg<br />

Übersetzung: Renate Wendel<br />

For a free promotional CD sampler including<br />

highlights from the ICA Classics CD catalogue,<br />

please email info@icaclassics.com.<br />

7<br />

For ICA Classics<br />

Executive Producer/Head of Audio: John Pattrick<br />

Music Rights Executive: Aurélie Baujean<br />

Head of DVD: Louise Waller-Smith<br />

Executive Consultant: Stephen Wright<br />

Remastering: Peter Reynolds (Reynolds Mastering)<br />

Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry note & translations<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Booklet editing: WLP Ltd<br />

Art direction: Georgina Curtis for WLP Ltd<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Technical Information<br />

TC M6000 Mastering Processor<br />

Lexicon 300 Reverb<br />

JBL, Genelec & PMC Moni<strong>to</strong>r Speakers<br />

Todd Electronics cus<strong>to</strong>m built Pre amp/Switcher,<br />

Digital Power Amp and Metering Unit<br />

STAX Electrostatic headphones<br />

Sonic soundBlade HD and Bias Peak Pro 7 Non Linear Editing Systems<br />

Izo<strong>to</strong>pe RX II Advanced and Algorithmics Renova<strong>to</strong>r software<br />

Mono ADD<br />

Original broadcasts from Radio Nacional de España (Beethoven)<br />

& Radio Suisse Romande (Smetana)<br />

WARNING:<br />

All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring,<br />

lending, public performance and broadcasting prohibited.<br />

Licences for public performance or broadcasting may be obtained<br />

from Phonographic Performance Ltd., 1 Upper James Street,<br />

London W1F 9DE. In the United States of America unauthorised<br />

reproduction of this recording is prohibited by Federal law and<br />

subject <strong>to</strong> criminal prosecution.<br />

Made in Austria

Also available on CD and digital <strong>download</strong>:<br />

ICAC 5000<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos.1 & 3<br />

New Philharmonia Orchestra · Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5001<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.2 ‘Resurrection’<br />

Stefania Woy<strong>to</strong>wicz · Anny Delorie<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor u. Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

William Steinberg<br />

ICAC 5006<br />

Verdi: La traviata<br />

Maria Callas · Cesare Valletti · Mario Zanasi<br />

The Covent Garden Opera Chorus & Orchestra<br />

Nicola Rescigno · Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5007<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.1 ‘Winter Dreams’<br />

Stravinsky: The Firebird Suite (1945 version)<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5003<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Chopin · Falla<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Chris<strong>to</strong>ph von Dohnányi · Arthur Rubinstein<br />

Gramophone Edi<strong>to</strong>rs’ Choice<br />

ICAC 5004<br />

Haydn: Piano Sonata No.62<br />

Weber: Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Schumann · Chopin · Debussy<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter<br />

Diapason d’or<br />

ICAC 5008<br />

Liszt: Rhapsodie espagnole<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.2<br />

CPE Bach · Couperin · Scarlatti<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5019<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.1<br />

Elgar: Enigma Variations<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult<br />

8<br />

9

ICAC 5021<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.3 · Debussy: La Mer<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor · Kölner Domchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Dimitri Mitropoulos<br />

Toblacher Komponierhäuschen <strong>International</strong><br />

Record Prize 2011<br />

ICAC 5022<br />

Puccini: Tosca<br />

Renata Tebaldi · Ferruccio Tagliavini · Ti<strong>to</strong> Gobbi<br />

The Covent Garden Opera Chorus & Orchestra<br />

Francesco Molinari-Pradelli<br />

ICAC 5035<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.4 · Mussorgsky: A Night<br />

on the Bare Mountain (‘Sorochinsky Fair’ version)<br />

Prokofiev: ‘The Love for Three Oranges’ Suite<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

ICAC 5036<br />

Shostakovich: Symphony No.10<br />

Tchaikovsky · Rimsky-Korsakov<br />

USSR State Symphony Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5032<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.4<br />

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Hallé Orchestra · Sir John Barbirolli<br />

London Philharmonic Orchestra · Kirill Kondrashin<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5033<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.3<br />

Waltraud Meier · E<strong>to</strong>n College Boys’ Choir<br />

London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra<br />

Klaus Tennstedt<br />

Choc de Classica · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAC 5045<br />

Chopin: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.4<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer · Chris<strong>to</strong>ph von Dohnányi<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Claudio Arrau<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5046<br />

Rossini: Il barbiere di Siviglia<br />

Rolando Panerai · Teresa Berganza · Luigi Alva<br />

The Covent Garden Opera Chorus & Orchestra<br />

Carlo Maria Giulini<br />

10<br />

11

ICAC 5047<br />

Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night’s Dream<br />

Beethoven: Symphony No.8<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor · Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer<br />

ICAC 5048<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Chopin · Liszt · Schumann · Albéniz<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Rudolf Kempe<br />

Julius Katchen<br />

ICAC 5061<br />

Verdi: Falstaff<br />

Fernando Corena · Anna Maria Rovere · Fernanda Cadoni<br />

Glyndebourne Opera Chorus<br />

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Carlo Maria Giulini<br />

ICAC 5063<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.3<br />

Elgar: Symphony No.1<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5053<br />

Holst: The Planets<br />

Britten: Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

ICAC 5054<br />

Beethoven: Missa solemnis<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

William Steinberg<br />

ICAC 5068<br />

Verdi: Requiem · Rossini: Overtures<br />

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Igor Markevitch<br />

ICAC 5069<br />

Rachmaninov: The Bells<br />

Prokofiev: Alexander Nevsky<br />

BBC Symphony Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

12<br />

13

ICAC 5077<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Debussy · Prokofiev<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Mario Rossi<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5078<br />

Rachmaninov: Symphony No.2<br />

Bernstein: Candide – Overture<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

London Symphony Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5081<br />

Schumann: Symphony No.4<br />

Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien – Suite<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

Guido Cantelli<br />

ICAC 5084<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Bagatelles op.126 Nos. 1, 4 & 6<br />

Piano Sonata No.29 ‘Hammerklavier’<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter<br />

ICAC 5079<br />

Grieg · Liszt: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s<br />

Lully · Scarlatti<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Georges Tzipine · André Cluytens<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5080<br />

Mahler: Das klagende Lied<br />

Janáček: The Fiddler’s Child<br />

Teresa Cahill · Janet Baker · Robert Tear · Gwynne Howell<br />

BBC Symphony Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

ICAC 5085<br />

Chopin: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos. 1 & 2<br />

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Chris<strong>to</strong>pher Adey<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Richard Hickox<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

ICAC 5086<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos. 2 & 4<br />

Sinfonia Varsovia<br />

Jacek Kaspszyk<br />

Ingrid Jacoby<br />

14<br />

15