Digitus Impudicus: The Middle Finger and the Law - Wired

Digitus Impudicus: The Middle Finger and the Law - Wired

Digitus Impudicus: The Middle Finger and the Law - Wired

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

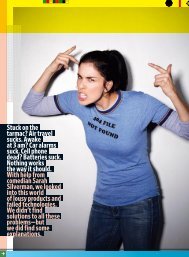

1484 University of California, Davis [Vol. 41:1403<br />

statement to include direct verbal criticism <strong>and</strong> challenges to most<br />

government officials, 527 as long as <strong>the</strong> speech does not rise to <strong>the</strong> level<br />

of fighting words, obscenity, or defamation. <strong>The</strong> digitus impudicus<br />

does not fall under any of <strong>the</strong>se exceptions. 528 Thus, <strong>the</strong> government<br />

cannot constitutionally prohibit its use, except in <strong>the</strong> limited<br />

circumstances in which such a prohibition is essential to serving <strong>the</strong><br />

missions of our educational <strong>and</strong> judicial systems. While targets of <strong>the</strong><br />

gesture may find it impolite, insulting, offensive, vulgar, rude, or<br />

crude, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court in Houston v. Hill eloquently stated that “<strong>the</strong><br />

First Amendment recognizes, wisely we think, that a certain amount<br />

of expressive disorder not only is inevitable in a society committed to<br />

individual freedom, but must itself be protected if that freedom would<br />

survive.” 529 In o<strong>the</strong>r words, even if “[t]hese days, ‘<strong>the</strong> bird’ is flying<br />

“[t]he freedom of individuals verbally to oppose or challenge police action without<br />

<strong>the</strong>reby risking arrest is one of <strong>the</strong> principal characteristics by which we distinguish a<br />

free nation from a police state”); Rutzick, supra note 236, at 10 (“To close <strong>the</strong> door on<br />

<strong>the</strong> most vigorous political protest would seem to do far more harm in <strong>the</strong> long run<br />

than <strong>the</strong> likelihood in <strong>the</strong> short run of violent reactive conduct [by a public authority<br />

figure] or harm to <strong>the</strong> ‘sensibilities.’”).<br />

527 Authority figures <strong>the</strong>oretically are less likely to be provoked to a violent<br />

reaction or to suffer harmed sensibilities than private citizens. See Hill, 482 U.S. at<br />

453, 461 (striking down city ordinance that proscribed “interrupt[ing] a police officer<br />

in <strong>the</strong> performance of his or her duties”); see also Webster v. City of New York, 333 F.<br />

Supp. 2d 184, 189-92, 201-02 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) (holding that partygoers’ comments<br />

toward police constituted protected criticism of officers’ actions where one<br />

“hysterical” partygoer was “screaming [her] head off,” <strong>and</strong> several of her companions<br />

loudly questioned whe<strong>the</strong>r police had authority to make any arrests during hostile<br />

encounter between police <strong>and</strong> citizens). Based on <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong>ir work, authority<br />

figures — especially police officers — are expected to tolerate some potentially<br />

offensive speech activity. See Lewis v. New Orleans, 408 U.S. 913, 913 (1972)<br />

(Powell, J., concurring) (suggesting that fighting words exception to First Amendment<br />

may apply differently when words are addressed to police officer ra<strong>the</strong>r than to<br />

ordinary citizen, because officers are “trained to exercise a higher degree of restraint”);<br />

see also Rutzick, supra note 236, at 10 (“Whatever is assumed about <strong>the</strong> reaction of <strong>the</strong><br />

average individual to offensive words, police are employed to keep <strong>the</strong> peace ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than breach it <strong>and</strong> are assumed to be trained to remain calm in <strong>the</strong> face of citizen<br />

anger . . . .”).<br />

528 See Sullivan, 376 U.S. at 283 (holding that states may impose liability for<br />

libelous speech in limited circumstances); supra Part II.A (arguing that <strong>the</strong> middle<br />

finger gesture, when used alone, does not constitute fighting words); supra Part II.B<br />

(arguing that <strong>the</strong> middle finger gesture does not fall within scope of legal definition of<br />

obscenity).<br />

529 Hill, 482 U.S. at 472.