The Second Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions

The Second Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions

The Second Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Henry Ernest Dudeney: Engl<strong>and</strong>’s Greatest Puzzlist 33<br />

articles for the English magazine Tit-Bits, <strong>and</strong> later they<br />

arranged to exchange puzzles for their magazine <strong>and</strong> newspaper<br />

columns. This may explain the large amount <strong>of</strong> duplication<br />

in the published writings <strong>of</strong> Loyd <strong>and</strong> Dudeney.<br />

Of the two, Dudeney was probably the better mathematician.<br />

Loyd excelled in catching the public fancy with<br />

manufactured toys <strong>and</strong> advertising novelties. None <strong>of</strong><br />

Dudeney’s creations had the world-wide popularity <strong>of</strong> Loyd’s<br />

“14-15” puzzle or his “Get Off the Earth” paradox involving a<br />

vanishing Chinese warrior. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, Dudeney’s<br />

work was mathematically more sophisticated (he once<br />

described the rebus or picture puzzle, <strong>of</strong> which Loyd produced<br />

thous<strong>and</strong>s, as a “juvenile imbecility” <strong>of</strong> interest only to the feeble-minded).<br />

Like Loyd, he enjoyed clothing his problems<br />

with amusing anecdotes. In this he may have had the assistance<br />

<strong>of</strong> his wife Alice, who wrote more than 30 romantic novels<br />

that were widely read in her time. His six books <strong>of</strong> puzzles<br />

(three are collections assembled after his death in 1930)<br />

remain unexcelled in the literature <strong>of</strong> puzzledom.<br />

Dudeneys‘s first book, <strong>The</strong> Canterbury <strong>Puzzles</strong>, was published<br />

in 1907. It purports to be a series <strong>of</strong> quaint posers propounded<br />

by the same group <strong>of</strong> pilgrims whose tales were recounted<br />

by Chaucer. “I will not stop to explain the singular manner in<br />

which they came into my possession,” Dudeney writes, “but<br />

[will] proceed at once….. to give my readers an opportunity <strong>of</strong><br />

solving them.” <strong>The</strong> haberdasher’s problem, found in this<br />

book, is Dudeney’s best-known geometrical discovery. <strong>The</strong><br />

problem is to cut an equilateral triangle into four pieces that<br />

can then be reassembled to form a square.<br />

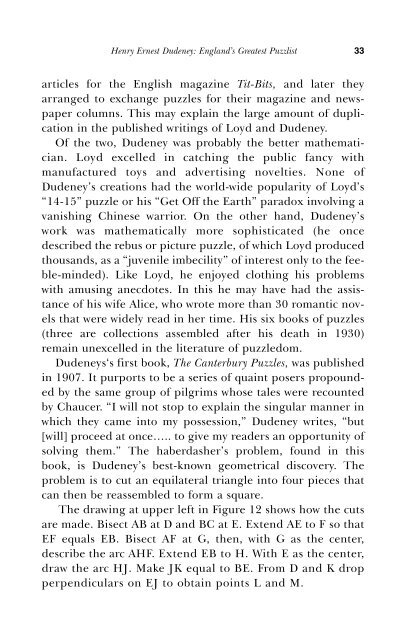

<strong>The</strong> drawing at upper left in Figure 12 shows how the cuts<br />

are made. Bisect AB at D <strong>and</strong> BC at E. Extend AE to F so that<br />

EF equals EB. Bisect AF at G, then, with G as the center,<br />

describe the arc AHF. Extend EB to H. With E as the center,<br />

draw the arc HJ. Make JK equal to BE. From D <strong>and</strong> K drop<br />

perpendiculars on EJ to obtain points L <strong>and</strong> M.