Public Attitudes and Preferences for Upland Landscapes - Defra

Public Attitudes and Preferences for Upland Landscapes - Defra

Public Attitudes and Preferences for Upland Landscapes - Defra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Public</strong> <strong>Attitudes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Preferences</strong> <strong>for</strong> Upl<strong>and</strong><br />

L<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

A summary of existing evidence on how the broader public perceive<br />

<strong>and</strong> value the English Upl<strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

March 2011<br />

Short evidence review prepared <strong>for</strong> <strong>Defra</strong>’s Agricultural Change <strong>and</strong> Environment<br />

Observatory. Research report no. 24.<br />

Principal contact: Caryl Williams (caryl.williams@defra.gsi.gov.uk)<br />

Summary<br />

Hill farming shapes the management of the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> has considerable wider cultural <strong>and</strong><br />

ecosystem impacts. Recognising the value of these impacts <strong>for</strong> different groups – upl<strong>and</strong><br />

communities, visitors <strong>and</strong> the wider public - is a key consideration in the context of defining future<br />

policies <strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong>s l<strong>and</strong> management.<br />

This short paper draws on a range of existing studies to explore public attitudes to different<br />

features of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes, the public’s preferences <strong>for</strong> the future of the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> how the<br />

public value typical upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes.<br />

Key conclusions:<br />

- The upl<strong>and</strong>s deliver a range of cultural services <strong>for</strong> different individuals <strong>and</strong><br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing individual preferences is complex.<br />

- Upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes provide recreational benefits as well as a sense of heritage (e.g.<br />

through historic man-made features) <strong>and</strong> contribute to a sense of local identity.<br />

- Broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> heather moor are valued by the public as features of the<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape. However, a significant proportion of respondents across studies favour<br />

the maintenance of a l<strong>and</strong>scape that is similar to today’s l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

- Individual relationships with <strong>and</strong> preferences <strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes are likely to be<br />

influenced by occupational class, education, ethnicity, age <strong>and</strong> other factors.<br />

- Respondents were willing to pay in principle to protect upl<strong>and</strong> National Parks but the<br />

percentage of individuals willing to pay varied between samples (from 46% to 82%). This<br />

is likely, in part to reflect the different methodologies employed.<br />

- The public’s willingness to pay (WtP) <strong>for</strong> single national parks/upl<strong>and</strong> areas varied<br />

considerably within <strong>and</strong> between studies. Between studies this is likely to reflect<br />

differences in methodology. However inter-regional variation identified within one study<br />

suggested that both demographic factors <strong>and</strong> the existing composition of upl<strong>and</strong> areas<br />

(e.g. the relative abundance of different features) can influence respondents’ WtP.<br />

Depth of evidence <strong>and</strong> implications <strong>for</strong> future work:<br />

- Methodological approaches adopted by the studies vary extensively <strong>and</strong>, as a<br />

consequence, studies were not always readily comparable or transferable to represent<br />

conclusive public views on upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> preferences.<br />

- Within the work reviewed, considerably less attention is given to the preferences of the<br />

‘general public’ (indirect beneficiaries who also contribute to agricultural support in the<br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s) than is given to the views of upl<strong>and</strong> residents <strong>and</strong> visitors.<br />

- The use of in-depth approaches to consider in more detail how the public perceive the<br />

interaction between the different services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s would allow a more indepth<br />

exploration of respondents’ preferences <strong>and</strong> would also shed light on other factors<br />

influencing the public’s WtP – including proposed payment vehicle.<br />

1

Table of Contents<br />

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3<br />

1.1.Background.............................................................................................................. 3<br />

1.2.Objectives ................................................................................................................ 5<br />

1.3.Methodology ............................................................................................................ 5<br />

2. Studies Reviewed ....................................................................................................... 6<br />

2.1. Sampling <strong>and</strong> representation .................................................................................. 6<br />

2.2. Limitations of available evidence ............................................................................ 6<br />

3. Factors influencing the public’s interaction with upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes ................... 7<br />

4. The public’s experience of individual upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape features ......................... 9<br />

5. <strong>Public</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the relationship between agriculture <strong>and</strong> upl<strong>and</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape features ....................................................................................................... 10<br />

6. <strong>Preferences</strong> <strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes (<strong>and</strong> services) ............................................... 11<br />

6.1. Overview of preferences from studies reviewed ................................................... 11<br />

6.2. Impact of sampling <strong>and</strong> responded characteristics on preferences ...................... 16<br />

6.3.Role of preference strength ................................................................................... 17<br />

7. Valuation of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes .............................................................................. 18<br />

7.1. Overview of Willingness to Pay (WtP) values from reviewed studies ................... 18<br />

7.2. Limitations of Contingent Valuation studies .......................................................... 24<br />

8. Conclusions <strong>and</strong> further research ........................................................................... 24<br />

9. Overview of referenced studies ............................................................................... 26<br />

2

1. Introduction<br />

1.1. Background<br />

There is no statutory definition of the English upl<strong>and</strong>s but a regularly adopted definition is that<br />

of l<strong>and</strong> categorised as “Less Favoured Areas (LFA)”, the EU classification <strong>for</strong> socially <strong>and</strong><br />

economically disadvantaged agricultural areas. The 9 upl<strong>and</strong> regions on which <strong>Defra</strong> have based<br />

this categorization are described (from an agricultural perspective) <strong>and</strong> mapped geographically in<br />

<strong>Defra</strong>’s statistical notice on the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> other LFAs 1 . Research 2,3 indicates that upl<strong>and</strong><br />

farming is facing real pressures <strong>and</strong> a reduction or significant change to the nature of upl<strong>and</strong><br />

agriculture could there<strong>for</strong>e have a major impact on what upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes look like in the future,<br />

as well as on the other benefits delivered. The visual quality of the l<strong>and</strong>scape requires<br />

sustainable l<strong>and</strong> management but this is dependent on an in<strong>for</strong>med underst<strong>and</strong>ing of what the<br />

public value.<br />

The special status of upl<strong>and</strong> regions - most have separate local governance<br />

arrangements (National Parks), l<strong>and</strong>scape protection status (e.g. Areas of Outst<strong>and</strong>ing Natural<br />

Beauty), special conservation designation (e.g. Sites of Special Scientific Interest) - means that<br />

they are a resource of national significance. Although there is distinct variation between different<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> regions, farming is a key feature associated with the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> has considerable<br />

cultural <strong>and</strong> environmental significance. This is because of the interdependence between farming<br />

<strong>and</strong> food production, wider management of l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> ecosystems, recreation <strong>and</strong> tourism 4 . Some<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> regions also feature unique tenure <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-management systems (e.g. commons <strong>and</strong><br />

grouse moor management) which have an impact on the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> add to the complexity of<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> farming systems. The non-production goods which upl<strong>and</strong> farming provides (e.g. the<br />

maintenance of the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>for</strong> recreational use etc.) are often cited as justification <strong>for</strong> the<br />

continued financial support of upl<strong>and</strong> farmers (see discussion in Hodge, 2000). However, as<br />

Harvey (2003) proposes, in order to ensure that agricultural activities provide the optimal level of<br />

public goods, it is not only necessary to separate financial support <strong>for</strong> broader public goods from<br />

payments <strong>for</strong> agricultural production but it is also important to identify the attributes of public<br />

goods <strong>and</strong> to determine their value to members of the public that benefit from them. Importantly,<br />

Harvey emphasises the need to recognise different public preferences in the design of rural<br />

policy l<strong>and</strong>-use.<br />

The Ecosystems Approach is an increasingly common approach to valuing all of the<br />

services delivered in any given area. Ecosystem services can be categorised into 4 overarching<br />

groups 5 :<br />

• Regulating services: the benefits derived from the way ecosystem processes are<br />

regulated such as water purification, air quality maintenance <strong>and</strong> climate regulation.<br />

• Provisioning services: the products obtained from ecosystems such as food, fibre<br />

<strong>and</strong> medicines.<br />

1 http://www.defra.gov.uk/evidence/statistics/foodfarm/enviro/farmpractice/documents/FPS2009upl<strong>and</strong>s.pdf<br />

2 http://www.defra.gov.uk/evidence/statistics/foodfarm/enviro/observatory/research/documents/upl<strong>and</strong>s-indepth.pdf<br />

3 http://www.defra.gov.uk/evidence/statistics/foodfarm/enviro/observatory/research/documents/Upl<strong>and</strong>sFPS_report09.p<br />

df<br />

4 http://www.defra.gov.uk/evidence/statistics/foodfarm/enviro/observatory/research/documents/upl<strong>and</strong>s2010.pdf<br />

5 http://www.defra.gov.uk/environment/policy/natural-environ/documents/eco-actionplan.pdf<br />

3

• Cultural services: services providing non-material benefits from ecosystems such as<br />

spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation <strong>and</strong> aesthetic<br />

experiences.<br />

• Supporting services: many ecosystem services are necessary <strong>for</strong> the production of<br />

all other ecosystem services from which society benefits, such as soil <strong>for</strong>mation <strong>and</strong><br />

nutrient cycling.<br />

Figure 1 (below) from the <strong>Defra</strong> report “Provision of Ecosystem Services through<br />

Environmental Stewardship” (2009) illustrates how prescribed changes in hill farming<br />

management (under Environment Stewardship) can affect the provision of ecosystem services;<br />

<strong>for</strong> example reducing agricultural intensity can lead to less food (shown as orange) but more<br />

regulating (e.g. water quality), cultural (e.g. heritage) <strong>and</strong> biodiversity services (shown as<br />

green/dark green). Promoting some of the cultural services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s (e.g.<br />

through an environmental stewardship scheme) will also impact on other services; <strong>for</strong> example a<br />

positive impact on biodiversity. <strong>Defra</strong>’s <strong>for</strong>thcoming publication - National Ecosystem Assessment<br />

Scenarios more explicitly illustrates the impacts of trade-offs resulting from social <strong>and</strong> political<br />

priorities on a range of ecosystems (<strong>Defra</strong> – <strong>for</strong>thcoming a). Although the public do not take into<br />

account all of the services provided by the upl<strong>and</strong>s when they visit or value them, there are<br />

various opportunities to involve the public in how we can better underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> capture the value<br />

of the goods delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> particularly by hill farming.<br />

Figure 1: Potential net service delivery (marginal change) in the upl<strong>and</strong>s under Environmental<br />

Stewardship (positive <strong>and</strong> negative)*<br />

Source: Provision of Ecosystem Services Through Environmental Stewardship, <strong>Defra</strong> 2009<br />

*The colours indicating impact follow the principle of a Red, Amber, Green (RAG) rating with dark green indicating<br />

considerable positive impacts, light green indicating some positive impacts, amber indicating no-change <strong>and</strong> red<br />

indicating negative impacts.<br />

The comprehensive report commissioned by Natural Engl<strong>and</strong> “Economic valuation of<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> ecosystem services” (Economics <strong>for</strong> the Environment 2009) directly seeks to value three<br />

cultural services delivered in a number of upl<strong>and</strong> case studies (many of the UK stated<br />

preferences studies used to in<strong>for</strong>m the case studies are included separately in this review). The<br />

three cultural services identified are: the use <strong>and</strong> enjoyment of upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>for</strong> outdoor recreation;<br />

the use <strong>and</strong> enjoyment of upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>for</strong> field sports; <strong>and</strong> the non-use values of historic <strong>and</strong> cultural<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes. In reality however, it is very difficult to effectively capture data on the non-use value<br />

of ecosystems (or to disaggregate this from use values) <strong>and</strong> this is reflected in the greater focus<br />

given to recreational use values in the studies reviewed here. A further difficulty is that of<br />

disaggregating the cultural services provided by the l<strong>and</strong>scape (as defined in the Ecosystems<br />

Approach) from other services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s (e.g. biodiversity) <strong>and</strong> this is considered<br />

further in Section 6, below.<br />

4

Although care must be taken not to double count the value of individual services delivered<br />

by the upl<strong>and</strong>s (by considering both their known market value <strong>and</strong> the public’s stated<br />

preferences), there is also some value in engaging the public in considering the non-cultural<br />

services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s (e.g. l<strong>and</strong>scape preservation Vs carbon regulation). Making<br />

respondents more aware of all of the services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the trade-offs<br />

between them will allow respondents to express more in<strong>for</strong>med choices about the future of the<br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s, putting their own cultural preferences <strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape in the wider ecosystem context.<br />

Based on the ecosystems approach there are a growing number of innovative payments <strong>for</strong><br />

ecosystem services (PES) schemes, many of which are relevant to farming in the upl<strong>and</strong> context.<br />

The principle is one where payments to l<strong>and</strong> managers (including from private sector) can be<br />

made to undertake actions that increase the quality <strong>and</strong> quantity of desired ecosystem services<br />

e.g. reducing diffuse pollution to improve water quality. SCaMP (Sustainable Catchment<br />

Management Programme) is an example of an on-going PES scheme delivering multiple<br />

ecosystem benefits; improving biodiversity, stabilising water quality, supporting rural<br />

communities, enhancing l<strong>and</strong>scape, reducing peat carbon emissions, protecting carbon stores<br />

<strong>and</strong> aiding fragile habitats to withst<strong>and</strong> future climate change.<br />

1.2. Objectives<br />

It is advocated that different groups of stakeholders with various degrees <strong>and</strong> types of interest<br />

are involved in decisions on ecosystem services (<strong>Defra</strong> – <strong>for</strong>thcoming b). This can range from<br />

active stakeholders who often have an invested interest in one or more ecosystem service (<strong>for</strong><br />

example, farmers <strong>and</strong> water companies, see Doungall et al 2006) to members of the general<br />

public but given the need to limit the scope of this paper, it is the perspective of the public in<br />

general which is of primary concern here. In a minority of the studies considered here, some<br />

attention is given to the potential trade-offs between different kinds of services (e.g. provisioning<br />

services <strong>and</strong> cultural services) but a lack of consideration of the broader services delivered by<br />

the upl<strong>and</strong>s is identified as an evidence gap.<br />

This paper will:<br />

- Discuss some key methodological issues <strong>and</strong> consider the different benefits derived from<br />

the upl<strong>and</strong>s by different groups of people;<br />

- Explore in detail the aesthetic, recreational <strong>and</strong> other experiential benefits which<br />

individuals derive from the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> how this is reflected in public preferences;<br />

- Consider the potential cultural <strong>and</strong> recreational value of the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>for</strong> different<br />

individuals.<br />

1.3. Methodology<br />

This paper predominantly discusses primary research studies which consider the public’s<br />

attitude toward <strong>and</strong>/or valuation of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes. Although the review takes into account<br />

some key studies that do not specifically focus on the upl<strong>and</strong>s (largely carried out on behalf of<br />

<strong>Defra</strong>), these are drawn upon to contextualise the upl<strong>and</strong>s focused studies, especially in terms of<br />

public attitude toward environmental change <strong>and</strong> toward agriculture more generally. However, all<br />

of the studies summarised in sections 6 <strong>and</strong> 7 of this review are specifically focused on the<br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s. Studies specifically on public attitudes toward the upl<strong>and</strong>s were identified through nonsystematic<br />

searches using an internet search engine <strong>and</strong> relevant references from reviewed<br />

studies were identified <strong>and</strong> in turn reviewed. Although studies from outside of Great Britain are<br />

excluded, studies from Scotl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Wales are included. The studies reviewed date from 1993 to<br />

present (with the vast majority published after 2000) <strong>and</strong> so some caution should be exercised<br />

when comparing studies, where differences may reflect broader social shifts over time. Given the<br />

approach adopted, this review does not provide systematic coverage of all relevant studies but<br />

highlights key themes emerging from the literature <strong>and</strong> areas where a systematic evidence<br />

assessment or further primary research could add value.<br />

5

2. Studies reviewed<br />

The table in section 9 lists all of the studies considered in this review. For the studies<br />

involving valuation based on the public’s stated preferences there is a predominance of studies<br />

focused on l<strong>and</strong>scapes within National Parks. Although this may raise concerns as to whether<br />

attitudes to upl<strong>and</strong> National Parks are representative of the public’s attitude to upl<strong>and</strong> areas more<br />

broadly 6 , the review does also take into account one large study focused on Severely<br />

Disadvantaged Areas (SDAs) more generally. A variety of research approaches have been used<br />

in the studies reviewed here including:<br />

• qualitative discussion groups exploring the qualities of different l<strong>and</strong>scape features<br />

<strong>and</strong> broadening our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the different benefits that l<strong>and</strong>scapes may<br />

contribute to the public (e.g. Research box et. al. 2009);<br />

• interviews or postal surveys to ascertain the general public’s preferences <strong>for</strong> the<br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s (Scottish Agricultural College 2005.), <strong>and</strong><br />

• interviews <strong>and</strong> surveys to determine an approximate monetary value <strong>for</strong> features<br />

of a given l<strong>and</strong>scape or a l<strong>and</strong>scape as a whole (Willis <strong>and</strong> Garrod 1993).<br />

2.1. Sampling <strong>and</strong> representation<br />

Despite the breadth of approaches adopted, the dominance of respondents who were<br />

local residents or visitors to upl<strong>and</strong> areas (compared to members of the wider public) is a<br />

weakness of the current evidence base <strong>and</strong> reflects a greater focus on the recreational use value<br />

of the upl<strong>and</strong>s over non-use cultural services Even within some of studies which have<br />

intentionally sought to include the views of the wider public, it is likely that the use of postal<br />

questionnaires has led to a degree of responder bias (as individuals that have an active interest<br />

in the environment or upl<strong>and</strong> areas are more likely to respond). As the majority of people making<br />

use of rural spaces are middle class <strong>and</strong> white (see literature review in Suckhall et al. 2009) the<br />

exclusion of non-direct users of the upl<strong>and</strong>s is likely to lead to the underrepresentation of the<br />

views of individuals from lower socio-economic groups <strong>and</strong> Black <strong>and</strong> Minority Ethnic groups<br />

(BME). In reality, individuals who do not actively engage with the upl<strong>and</strong> environment may value<br />

the non-use cultural services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> will benefit from some of the other<br />

services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s (e.g. water, food, the capacity of the upl<strong>and</strong>s to absorb<br />

carbon), <strong>and</strong> so their views should also be taken into account.<br />

2.2. Limitations of available evidence<br />

In their comprehensive evidence review on public attitude to environmental change,<br />

Upham et al. (2009) suggest that significant evidence already exists about why people value<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> how to measure these values <strong>and</strong> perceptions. However, the review also notes<br />

that the number of studies on attitudes to ecosystem <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape change (focused on the<br />

future) which take into account the reasons behind people’s preferences <strong>and</strong> go beyond<br />

immediate responses is low: “The potential <strong>for</strong> further research is substantial, but the scope or<br />

terms of this will need careful definition if the intention is to in<strong>for</strong>m policy. Most notably... it is<br />

important not to simply ask the public abstract / in principle questions: context, contingencies,<br />

trade-offs <strong>and</strong> choices are all key but are rarely explored”. This assertion is supported by the<br />

findings from this review.<br />

As noted, most of the studies reviewed here asked respondents about the l<strong>and</strong>scape as<br />

opposed to specific ecosystem services <strong>and</strong> as a result, few of the studies reviewed here have<br />

engaged the public in considering how services which may not be as strongly associated with the<br />

6 Across Engl<strong>and</strong>, National Parks account <strong>for</strong> around 40% of the LFA as a whole. However 97% of the North York<br />

Moors, 72% of the South West Moors <strong>and</strong> 68% of the Lake District are designated National Parks.<br />

6

l<strong>and</strong>scape (e.g. food <strong>and</strong> production <strong>and</strong> GHG absorption) relate to the recreational <strong>and</strong> cultural<br />

services primarily associated with the upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape. In focus groups intended to in<strong>for</strong>m a<br />

survey on Environmental Stewardship (ES) it was noted that respondents did not recognise the<br />

impact that environmental management (<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape change) may have on atmospheric<br />

greenhouse gases (FERA 2010); this highlights the need to provide respondents with more<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation in order to gain an in<strong>for</strong>med response about their overall preferences <strong>for</strong> ecosystems.<br />

The more detailed discussion of findings below does demonstrate that some respondents are<br />

already likely to also consider the role of biodiversity in the context of discussions of l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

(see Black, 2009 below), however, the broader factors which respondents are likely to consider in<br />

the absence of additional in<strong>for</strong>mation will reflect their own level of existing knowledge <strong>and</strong><br />

familiarity with upl<strong>and</strong> areas.<br />

Further to this, none of the studies reviewed explicitly distinguish between the recreational<br />

use services of the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> the cultural non-use services (as proposed by the EFTEC<br />

report <strong>for</strong> Natural Engl<strong>and</strong> 2009). The qualitative evidence considered here <strong>and</strong> the fact that<br />

some of the studies reviewed found that some members of the public were willing to pay to<br />

maintain the upl<strong>and</strong>s despite never having visited them, clearly demonstrate that the upl<strong>and</strong>s do<br />

provide non-use cultural services. However, in the majority of instances, it was impossible to<br />

distinguish as to whether respondents were valuing the use or non-use cultural services<br />

delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

The use of deliberative approaches, which in<strong>for</strong>m respondents sufficiently to allow them<br />

to consider trade-offs between the different services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s could help to<br />

address both of these limitations. Such approaches are becoming increasingly relevant with<br />

increased use of ecosystem services approaches. In addition, deliberative approaches could be<br />

particularly useful <strong>for</strong> considering public views on potential trade-offs between expenditure on<br />

ecosystem services (e.g. through agricultural subsidies). The use of approaches which include<br />

the views of stakeholders, including members of the public, <strong>and</strong> take into account their own<br />

values <strong>and</strong> insight, can also have the benefit of leading to more desirable <strong>and</strong> sustained policy<br />

outcomes (<strong>Defra</strong> – <strong>for</strong>thcoming b).<br />

3. Factors influencing public interaction with upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

Drawing on a review of existing evidence on how the public value agricultural l<strong>and</strong>scapes,<br />

Swannick et al. (2007) conclude that individuals’ perceptions of l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> the value they<br />

attach to it are likely to be influenced by:<br />

− age <strong>and</strong> socioeconomic status;<br />

− gender, although this has been relatively little explored;<br />

− cultural background <strong>and</strong> ethnic origin;<br />

− relationship with the l<strong>and</strong>scape in terms of status as residents/visitors or<br />

insiders/outsiders or urban/rural dwellers, with familiarity an important related factor;<br />

− use of the l<strong>and</strong>scape, <strong>for</strong> example differences between farmers, tourists <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

managers;<br />

− levels of educational attainment;<br />

− environmental value orientations which may or may not be correlated with another<br />

influential factor, membership of environmental organisations<br />

7

Age <strong>and</strong> socio-economic status are factors influencing the level of access to certain<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes. For example, individuals from lower occupational classes are less likely to make<br />

direct use of rural l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> green spaces than individuals from occupational classes A-C. 7<br />

Suckall et al. (2009) also found that children from a ‘middle class’ school in Sheffield reacted<br />

more favourably to the Peak District National Park than a similar group of children from a school<br />

in a more working class region of the same city. Individuals from BME groups were also unlikely<br />

to favour the upl<strong>and</strong>s over other places (<strong>for</strong> example an urban shopping mall) - although no<br />

attempt was made to determine how ethnicity relates to preferences independent of social class.<br />

However individuals who had been part of an environmental outreach scheme to increase the<br />

participation of individuals from BME groups in the countryside had more positive perceptions of<br />

the Peak District than a control group. This suggests that <strong>for</strong>ms of intervention which increase<br />

members of the public’s awareness <strong>and</strong> direct experiences of natural l<strong>and</strong>scapes may also<br />

influence preferences. A <strong>for</strong>thcoming customer segmentation study commissioned by <strong>Defra</strong><br />

which grouped individuals by lifestyle, attitudes <strong>and</strong> values (as opposed to socio-demographic<br />

factors only) also found that upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes were seen as challenging <strong>and</strong> unappealing by<br />

those in the segments ‘Good <strong>for</strong> the kids <strong>and</strong> me’ (young mothers), ‘Locally limited’ (lower<br />

income groups aged between 16-34) <strong>and</strong> ‘Reluctant <strong>and</strong> uninspired’ (aged between 34 <strong>and</strong> 54<br />

struggling with work, money <strong>and</strong> families) (<strong>Defra</strong> <strong>for</strong>thcoming c).<br />

SAC (2006) employed focus groups to explore public opinion on some of the more visible<br />

services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s. Although these focus groups included both urban <strong>and</strong> rural<br />

participants, all participants had a reasonably high level of engagement with the upl<strong>and</strong>s – i.e.<br />

the urban participants, from Sheffield, regularly visited the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>for</strong> recreational purposes.<br />

Despite this, there were still some obvious differences in the way in which the rural <strong>and</strong> urban<br />

groups related to the upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape – <strong>for</strong> example the urban group were more likely to<br />

describe the l<strong>and</strong>scape using words such as ‘photogenic’ <strong>and</strong> ‘tranquil’ while those residing in<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> areas suggested more personal <strong>and</strong> arguably emotional adjectives such as ‘inspiring’,<br />

‘vulnerable’, <strong>and</strong> ‘gr<strong>and</strong>eur’. Likewise, Research Box et al. (2009) found that, although<br />

respondents did not always find moorl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes important (with some noting that they felt<br />

too exposed within such l<strong>and</strong>scapes), moorl<strong>and</strong> was particularly important <strong>for</strong> those living in<br />

proximity to it. For example, <strong>for</strong> respondents in Exmoor, moorl<strong>and</strong> was considered to contribute<br />

greatly to local identity.<br />

Moving beyond socio-demographic variables, Research box et al. note in their study that<br />

there are four categories of factors that can influence the way that people experience the<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape: demographic factors (such as the above), situational factors (e.g. whether one<br />

interacts with the l<strong>and</strong>scape alone or in a group), awareness factors (e.g. degree of familiarity<br />

with the l<strong>and</strong>scape etc.) <strong>and</strong> preference factors (2009). Some of the studies reviewed here record<br />

the range of reasons why individuals engage with the Upl<strong>and</strong>s 8 . As the discussion on<br />

preferences <strong>and</strong> valuation (below) will show, the nature of respondents’ engagement with the<br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s impacts on both their preferences <strong>and</strong> willingness to pay <strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes.<br />

In a comprehensive review of evidence on attitudes to environmental change, Upham et<br />

al. (2009) look specifically at 3 broad types of environmental change - climate change, changes<br />

in ecosystems <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> energy technologies <strong>and</strong> transfer. The report considers a<br />

wider cross-section of the public than many of the studies focused specifically on the upl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> focuses on both broader environmental change <strong>and</strong> changes in l<strong>and</strong>scape. The report<br />

highlights some key general considerations about public attitudes which provide important<br />

7 Findings from Natural Engl<strong>and</strong>’s Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment 2009 –2010 survey<br />

http://naturalengl<strong>and</strong>.etraderstores.com/NaturalEngl<strong>and</strong>Shop/NECR049. Social-grade as used here is derived from the<br />

National Readership Study. Definitions from the grades are as follows: A =High managerial, administrative or<br />

professional; B = Intermediate managerial, administrative or professional; C1= Supervisory, clerical <strong>and</strong> junior<br />

managerial administrative or professional, C2 = Skilled manual workers, D = Semi <strong>and</strong> unskilled manual workers, E =<br />

State pensioners, casual or lowest grade workers, unemployed with state benefits only.<br />

8 As part of the study carried out by the Scottish Agricultural College on behalf of the Centre <strong>for</strong> Upl<strong>and</strong>s, respondents<br />

were asked about the activities they participate in when visiting the Upl<strong>and</strong>s. The three most common activities were<br />

walking, scenic driving <strong>and</strong> bird/wildlife watching respectively.<br />

8

context <strong>for</strong> how we interpret the public’s preferences (<strong>for</strong> example when the public express<br />

unqualified preferences as part of survey based studies). For example, it is likely that the public<br />

are less likely to be concerned about issues which they don’t anticipate will have a direct or<br />

immediate impact on them; respondents often rate climate change to be less of a concern than<br />

other factors (e.g. intensive agriculture) because the impacts of climate change are considered to<br />

be “further away” (p7). The fact that respondents may generally be positive about some <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

change (e.g. wind energy) but opposed to their development in a place to which they are<br />

attached, is also highlighted.<br />

Summary section 3<br />

- Individuals’ attitudes <strong>and</strong> preferences <strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape will depend on socio-demographic<br />

factors, the context in which they interact with the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> also the nature of the<br />

research approach – e.g. whether questions are specifically related to l<strong>and</strong>scape or cover<br />

broader issues such as biodiversity preservation.<br />

- Focus groups demonstrate that proximity of residence to upl<strong>and</strong> areas, socio-economic<br />

factors <strong>and</strong> ethnicity are all likely to impact on individuals’ relationships with upl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> their preferences. Engagement strategies <strong>and</strong> the provision of additional<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation may influence individual preferences.<br />

- People are more likely to be concerned about changes that will have an immediate or<br />

direct impact on them.<br />

4. The public’s experience of individual upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape features<br />

The Research Box report - “Experiencing L<strong>and</strong>scapes - capturing the cultural services<br />

<strong>and</strong> experiential qualities of l<strong>and</strong>scape” comprised a literature review <strong>and</strong> primary research using<br />

focus groups to explore the complex cultural <strong>and</strong> experiential services of various l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

(2009). As well as considering respondent’s attitudes to different l<strong>and</strong>scape types, the paper also<br />

considers how local residents relate specifically to their local Natural Character Area (NCA) 9 .<br />

Eight NCAs were selected including Exmoor (which was the only upl<strong>and</strong> NCA). This research is<br />

valuable in the context of this review as it provides some insight into the ways in which different<br />

members of the public relate to different l<strong>and</strong>scapes but also specifically explores some of the<br />

cultural <strong>and</strong> experiential benefits provided by key features associated with the upl<strong>and</strong>s (<strong>and</strong><br />

Exmoor particularly). However the authors acknowledge that the engagement of just local<br />

respondents in the research is a limitation <strong>and</strong> they imply that there is scope <strong>for</strong> further research<br />

involving those who are not direct users of services (but indirect beneficiaries).<br />

Hills were associated with recreation <strong>and</strong> generally found to be highly valued as<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes. Hills <strong>and</strong> mountains are strongly associated with escape, spiritual experiences <strong>and</strong><br />

inspiration (as are moors). Some of the other key features of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes explored<br />

included height, fields, walls <strong>and</strong> hedges, bogs <strong>and</strong> moorl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

- Height was considered integral to many l<strong>and</strong>scape experiences both <strong>for</strong> the exhilaration<br />

provided <strong>and</strong> the sense of putting things ‘in perspective’.<br />

- The contribution of field systems towards the look of the l<strong>and</strong> was considered worthy of<br />

protection. Fields were considered to deliver a sense of calm <strong>and</strong> tranquillity, as well as a<br />

sense of history <strong>and</strong> escapism. In general, fields were more important as part of “the<br />

whole view” than as something to interact with (due to lack of access) <strong>and</strong> respondents<br />

preferred irregular-shaped <strong>and</strong> small fields (as opposed to large fields with no<br />

boundaries).<br />

- The overall appeal of walls <strong>and</strong> hedges seems to derive from their association (along<br />

with farml<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> field-shapes) with a ‘quintessential’ English view. In this respect, walls<br />

9 Engl<strong>and</strong> has been divided into 159 NCAs each based on physiogeographic, l<strong>and</strong> use, historical <strong>and</strong> cultural<br />

attributes. See http://www.naturalengl<strong>and</strong>.org.uk/ourwork/l<strong>and</strong>scape/engl<strong>and</strong>s/character/areas/default.aspx<br />

9

were considered to contribute to a ‘pastoral’ scene. Specific hedges or walls were of<br />

interest in terms of nesting birds or lichen on the stonework, but also (especially with<br />

stone walls) of a sense that people had created them.<br />

- Bogs <strong>and</strong> marshes were considered to be important <strong>for</strong> birdwatchers <strong>and</strong> as a place to<br />

trap water <strong>and</strong> prevent flooding. A few people valued peat bogs <strong>for</strong> wider environmental<br />

reasons (e.g. as carbon sinks) but the mainstream generally felt that they did not deliver<br />

many cultural services on a widespread basis.<br />

- Moorl<strong>and</strong> was valued <strong>for</strong> its wildness <strong>and</strong> “bleakness” but moorl<strong>and</strong> areas were not<br />

always thought to be beautiful places by the majority of respondents. Generally, the<br />

sense of openness was considered to be the most important aspect of such l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

but heather, deer <strong>and</strong> rocky outcrops were features that contributed to the quality of the<br />

experience. Moorl<strong>and</strong> was perceived to deliver quite an intense experience, <strong>and</strong> could be<br />

seen as “inspiring” or “spiritual”, but was less likely to be “calming” or “historical”.<br />

Moorl<strong>and</strong>s were considered to be special l<strong>and</strong>scapes that were perceived to be truly wild<br />

with little perceived management.<br />

Although not a physical feature of the upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape, the sense of community <strong>and</strong><br />

the continuity of interaction between people <strong>and</strong> the environment over time was recorded as a<br />

highly valued feature of the upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>for</strong> a small sample of local residents from three North<br />

Pennines villages (L<strong>and</strong> Use Consultants <strong>and</strong> University of Sheffield (1998), referenced in<br />

Swannick et al. (2007). This contributed to a strong sense of identity <strong>and</strong> of links with the past.<br />

This finding supports the suggestion made by Swannick et al. (2007) that, l<strong>and</strong>scape is an area<br />

of l<strong>and</strong> consisting of the physical, natural, social <strong>and</strong> cultural dimensions of the environment <strong>and</strong><br />

the interactions between them.<br />

Summary section 4<br />

- The public value features such as historical man-made features, dry stone walls <strong>and</strong><br />

irregularly shaped fields because they give a sense of people’s continued interaction with<br />

the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> give the l<strong>and</strong>scape a ‘pastoral’ feel.<br />

- Moorl<strong>and</strong> is particularly important <strong>for</strong> those living in it <strong>and</strong> contributes a sense of local<br />

identity. It is also considered to have intense experiential qualities being described as<br />

inspiring <strong>and</strong> spiritual.<br />

5. <strong>Public</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the relationship between agriculture <strong>and</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

features<br />

Only one of the studies reviewed (SAC 2006) explicitly asked members of the public to<br />

consider the role of hill farming in delivering non-l<strong>and</strong>scape services. This research looked at the<br />

public’s appreciation of existing upl<strong>and</strong> features <strong>and</strong> their underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the relationship<br />

between agriculture <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scape. In general, respondents understood that a decrease in<br />

grazing would lead to an increase in scrub l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> other vegetation <strong>and</strong> these changes were<br />

not always viewed negatively. A survey designed to in<strong>for</strong>m the focus groups in this study asked<br />

respondents to indicate their level of agreement with a number of statements about agriculture.<br />

The intention was to focus respondents’ attention on the role of agriculture <strong>and</strong> the potential<br />

policy trade-offs that could be made in managing the upl<strong>and</strong>s. Overall, respondents agreed that a<br />

reduction in agriculture would mean that the l<strong>and</strong>scape would become less attractive <strong>and</strong> that<br />

rural communities <strong>and</strong> rural economies would suffer. However, just under half of respondents<br />

agreed that the quality of lakes <strong>and</strong> rivers would improve or that conditions would become more<br />

favourable <strong>for</strong> wildlife <strong>and</strong> there seemed to be considerably more uncertainty over these two<br />

statements. The Research Box study found that in Exmoor, both positive <strong>and</strong> negative effects<br />

were expressed in relation to agriculture’s influence on the l<strong>and</strong>scape. Several older participants<br />

noted that farmers were responsible <strong>for</strong> creating the l<strong>and</strong>scape of Exmoor but there was wide<br />

agreement that some new agricultural enterprises brought changes, especially “elephant grass”<br />

10

(<strong>for</strong> biomass energy) <strong>and</strong> extensive plastic sheeting, which were thought to be alien features in<br />

the Exmoor l<strong>and</strong>scape (2006).<br />

Summary section 5<br />

- Members of the public had some degree of underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the relationship between<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scape but there was some uncertainty in the interactions between<br />

agriculture <strong>and</strong> the wider environment.<br />

6. <strong>Preferences</strong> <strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> services<br />

6.1. Overview of preferences from studies reviewed<br />

A number of the studies reviewed here specifically asked members of the public about<br />

their preferences in terms of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape features <strong>and</strong> the results are summarised in Table<br />

1, below. It is difficult to compare results as different studies asked respondents to consider<br />

different attributes of the upl<strong>and</strong>s – with some considering l<strong>and</strong>scape only <strong>and</strong> others including<br />

biodiversity, socio-cultural factors <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> management. The variability is also likely to reflect<br />

sampling <strong>and</strong> the nature of the in<strong>for</strong>mation given to respondents during the interview/<br />

questionnaire process. Both broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> moorl<strong>and</strong> were generally valued by<br />

members of the public; grassl<strong>and</strong> is likely to be less favoured than woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> moorl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>,<br />

in studies considering whole l<strong>and</strong>scape change, respondents favoured situations where<br />

grassl<strong>and</strong> was marginally reduced or stayed the same (as opposed to situations where the<br />

proportion of grassl<strong>and</strong> increased). Despite this, within one study considering the public’s<br />

preferences in the context of whole l<strong>and</strong>scape change, nearly 50% of respondents favoured the<br />

existing l<strong>and</strong>scape over other types of l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

11

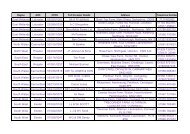

Table 1 Studies reviewed – summary of public preferences towards l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

Study <strong>Preferences</strong> Comments<br />

White P. C. L.<br />

<strong>and</strong> J. C. Lovett<br />

(Interview)<br />

(1999)<br />

White P. C. L.<br />

<strong>and</strong> J. C. Lovett<br />

(Questionnaire)<br />

(1999)<br />

Willis K.G <strong>and</strong><br />

G.D.Garrod<br />

(1991)<br />

Heather moorl<strong>and</strong><br />

Broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong><br />

Traditional grazing pasture<br />

Broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong><br />

Heather moorl<strong>and</strong><br />

Traditional grazing pasture<br />

Today’s l<strong>and</strong>scape:<br />

‘Conserved’ l<strong>and</strong>scape:<br />

Wild l<strong>and</strong>scape:<br />

‘Planned’ l<strong>and</strong>scape:<br />

Sporting:<br />

Ab<strong>and</strong>oned l<strong>and</strong>scape:<br />

Semi-intensive:<br />

Intensive:<br />

70%<br />

25%<br />

5%<br />

70%<br />

33%<br />

7%<br />

Residents<br />

50.2 %<br />

29.5%<br />

6.8%<br />

6.8%<br />

2.7%<br />

3.1%<br />

0.3%<br />

_<br />

Visitors<br />

47.2 %<br />

28.7%<br />

12.5%<br />

7.3%<br />

1%<br />

2.6%<br />

0.3%<br />

_<br />

Sample primarily based on visitors to the<br />

North York Moors approached in car parks<br />

where they were likely to stop to admire the<br />

view.<br />

Sample based on people residing near the<br />

North York Moors National Park <strong>and</strong> who had<br />

visited the park in the past. 66% of the<br />

sample visited the National Park <strong>for</strong> bird<br />

watching. Note published figures exceed<br />

100%.<br />

Respondents were asked <strong>for</strong> their<br />

preferences <strong>for</strong> management of a National<br />

Park <strong>and</strong> shown images which reflected the<br />

various management approaches. The<br />

‘conserved’ l<strong>and</strong>scape was an enhanced<br />

version of today’s l<strong>and</strong>scape with features<br />

such as broadleaved <strong>for</strong>est <strong>and</strong> dry stone<br />

walls accentuated.<br />

12

Black (2009) Rank† L<strong>and</strong>scape Biodiversity Combined Respondents were asked separately <strong>for</strong><br />

1<br />

An increase in An increase in An increase preferences as to l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> biodiversity.<br />

Woodl<strong>and</strong><br />

Blanket Bog in Blanket Once respondents were told how l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

Bog<br />

changes would impact on biodiversity they<br />

2<br />

An increase in Status Quo<br />

were asked to rank their most favoured<br />

Blanket Bog<br />

Status Quo option based on both l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong><br />

biodiversity combined.<br />

3<br />

Status Quo An increase in<br />

Grassl<strong>and</strong> An increase<br />

in Woodl<strong>and</strong><br />

Hanley et al<br />

(1998)<br />

4<br />

5<br />

Rank†<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

An increase in<br />

Heather Moor<br />

An increase in<br />

Grassl<strong>and</strong><br />

Woods<br />

Heather Moors<br />

Grassl<strong>and</strong><br />

Dry Stone Walls<br />

Archaeology<br />

An increase in<br />

Woodl<strong>and</strong><br />

An increase in<br />

Heather Moor<br />

An increase<br />

in Grassl<strong>and</strong><br />

An increase<br />

in Heather<br />

Moor<br />

Sample based on visitors to a specific<br />

Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) in<br />

Scotl<strong>and</strong>. (WtP figured are given in Table 4)<br />

13

Hanley et al<br />

(2007)<br />

The same study<br />

is also included in<br />

EFTEC (2006)<br />

“Economic<br />

Valuation of<br />

Environmental<br />

Impacts in the<br />

Severely<br />

Disadvantaged<br />

Areas” 10 .<br />

SAC <strong>for</strong> Centre<br />

<strong>for</strong> Upl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

(2005)<br />

Rank †<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Rank†<br />

1<br />

2<br />

Environmental l<strong>and</strong>scape: (heather moorl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> bog<br />

+5%, rough grassl<strong>and</strong> -3%, mixed <strong>and</strong> broadleaved<br />

woodl<strong>and</strong> +6%, field boundaries +10%, cultural<br />

heritage – no change)<br />

Environment <strong>and</strong> agricultural l<strong>and</strong>scape: (heather<br />

moorl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> bog +3%, rough grassl<strong>and</strong> -1%, mixed<br />

<strong>and</strong> broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> +4%, field boundaries<br />

+6%, cultural heritage – no change)<br />

Intensive/ab<strong>and</strong>oned l<strong>and</strong>scape: (heather moorl<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> bog -2%, rough grassl<strong>and</strong> +1%, mixed <strong>and</strong><br />

broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> +5%, field boundaries +2%,<br />

cultural heritage – rapid decline)<br />

Upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

Community <strong>and</strong> culture<br />

Used Choice Experiment (focused on 5<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape features) to determine implicit WtP<br />

<strong>for</strong> the impact on l<strong>and</strong>scape of three policy<br />

scenarios.<br />

Values here are given <strong>for</strong> the whole sample<br />

but there were some regional differences –<br />

e.g. the implicit prices of the cultural heritage<br />

attribute were<br />

very low in the North West region while they<br />

were quite high in the Yorkshire <strong>and</strong><br />

Humber region.<br />

Respondents were asked which of 3 upl<strong>and</strong><br />

‘attributes’ they favoured most. Details of the<br />

attributes are given in Table 3.<br />

3<br />

Farm management<br />

† Not all studies gave preferences as a percentage of the total sample (e.g. as the sample was broken down into a number of subgroups or respondents were<br />

asked to value individual l<strong>and</strong>scape components). Where this was the case, l<strong>and</strong>scape attributes are ranked in order of preference.<br />

10 http://www.defra.gov.uk/evidence/economics/foodfarm/reports/documents/SDA.pdf<br />

14

Hanley et al. (1998) employed a Choice Experiment 11 methodology to consider which<br />

features of the upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape were most valued. They found that respondents were willing to<br />

pay most to preserve woodl<strong>and</strong>, significantly less to preserve heather moorl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> least to preserve archaeology <strong>and</strong> dry stone walls. A second study by the same lead author<br />

(Hanley et al 2007) used respondents’ valuation of incremental changes in individual l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

features to calculate overall WtP <strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape change. However one likely weakness of this<br />

approach is that respondents do not have the opportunity to consider the interaction between<br />

individual l<strong>and</strong>scape features <strong>and</strong> the aesthetic value of the l<strong>and</strong>scape as a whole. A regression<br />

analysis employed in one study (Black 2009) indicates that l<strong>and</strong>scape provides more value to<br />

consumers than biodiversity. Both of these are public goods in that they are non-rival <strong>and</strong> nonexcludable,<br />

but l<strong>and</strong>scape is more accessible <strong>and</strong> recognisable than biodiversity. L<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

can be observed <strong>and</strong> enjoyed aesthetically more easily than biodiversity.<br />

Willis <strong>and</strong> Garrod (1991) adopted a visual whole l<strong>and</strong>scape approach taking into account<br />

the impacts of different management practices on the l<strong>and</strong>scape as a whole. Using a CV<br />

approach, they found that respondents favoured l<strong>and</strong>scapes that are similar to ‘today’s’<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape, or conserved l<strong>and</strong>scapes, where features such as hay meadows <strong>and</strong> broad-leaved<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests are enhanced <strong>and</strong> traditional buildings <strong>and</strong> dry-stone walls are well maintained. Intensive<br />

agricultural <strong>and</strong> semi-intensive agricultural l<strong>and</strong>scapes were the least favoured. These findings<br />

broadly reflect those of Hanley et al. (2007) who also considered l<strong>and</strong>scape change as a<br />

response to changes in l<strong>and</strong> management (although using a very different methodological<br />

approach <strong>and</strong> incorporating cultural change). A further study by Nick Hanley (not reviewed in<br />

detail here) focused on a small group of local residents in the Peak District National Park, also<br />

found that residents were willing to pay to preserve the current l<strong>and</strong>scape (<strong>and</strong> to prevent a move<br />

to a more intensively managed l<strong>and</strong>scape) 12 . This resistance to change is supported by findings<br />

on l<strong>and</strong>scapes more generally from the New Map of Engl<strong>and</strong> work in the south west. This<br />

research found that when offered a choice of future scenarios <strong>for</strong> the different l<strong>and</strong>scapes, there<br />

was an almost universal preference <strong>for</strong> alternatives which showed conservation, restoration, <strong>and</strong><br />

enhancement of the current l<strong>and</strong>scape (Swanwick, 2009 in Upham et al (2009: 52).<br />

Taking a somewhat broader approach which goes beyond l<strong>and</strong>scape alone <strong>and</strong> more<br />

explicitly incorporated biodiversity <strong>and</strong> social factors, the SAC study employed an Analytical<br />

Hierarchy Process (AHP) focused on three broad upl<strong>and</strong> attributes <strong>and</strong> their sub features. The 3<br />

broad attributes are described in table 3 below.<br />

When the attributes were broken down to their component parts, participants from both<br />

Manchester <strong>and</strong> Cumbria showed a very strong preference <strong>for</strong> wild plants, birds <strong>and</strong> mammals.<br />

The authors of the study also infer that with the exception of wildlife, respondents in Cumbria had<br />

stronger preferences <strong>for</strong> qualities associated with traditional farming <strong>and</strong> community culture than<br />

<strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape whereas the Manchester sample showed no such preferences. These sample<br />

differences do not necessarily reflect urban/rural differences as both samples included individuals<br />

from urban <strong>and</strong> rural areas.<br />

11 Choice experiment (CE) is one of two common approaches used to determine non-market values based<br />

of the public’s stated preferences. CE approaches ask respondents to choose between different possible<br />

scenarios which have a number of attributes, including a price. A series of such choices allows the<br />

researchers to determine which attributes respondents favour most <strong>and</strong> how much they are willing to pay<br />

<strong>for</strong> them. The second approach, Contingent Valuation (CV) is discussed at length in section 7. CV surveys<br />

typically ask how much money people would be willing to pay (or willing to accept) to maintain the<br />

existence of (or be compensated <strong>for</strong> the loss of) a specific environmental feature. The approach can be<br />

open ended (where WtP is decided entirely by the respondent) or respondents can choose how much they<br />

are willing to pay from a series of paired values (dichotomous choice).<br />

12 http://old.moors<strong>for</strong>thefuture.org.uk/mftf/downloads/conferences/RELU_March_2010/Leaflet%204.%20Valuation.pdf<br />

15

Table 2 SAC research – Upl<strong>and</strong> characteristics<br />

Upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

• Upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes can be characterised as providing scenic views over the fells <strong>and</strong> moors.<br />

• The lower lying l<strong>and</strong>scape is characterised by traditional farm buildings <strong>and</strong> dry stone walls.<br />

• The less intensive <strong>for</strong>m of agriculture in upl<strong>and</strong> areas results in greater peace <strong>and</strong> tranquillity;<br />

• <strong>and</strong> offers greater opportunities <strong>for</strong> wild plants, birds <strong>and</strong> animals.<br />

Traditional farm management<br />

• Hill farming has not seen the large changes experienced by lowl<strong>and</strong> farming in recent decades,<br />

which has involved more intensive farming practices <strong>and</strong> specialisation.<br />

• Hill farms are typically small family farms, with close links to the local community.<br />

• This <strong>for</strong>m of farming involves a number of traditional skills such as shepherding, maintaining dry<br />

stone walls, <strong>and</strong> common l<strong>and</strong> management.<br />

Community culture<br />

• Local communities are closely linked with hill farming through activities such as local shows <strong>and</strong><br />

other community activities resulting in a strong local culture.<br />

• These close links also mean that there are strong social networks within upl<strong>and</strong> communities.<br />

6.2. Impact of sampling <strong>and</strong> responder characteristics on preferences<br />

One important factor - influencing both willingness to pay <strong>and</strong> preferences - which may<br />

merit further consideration here is the characteristics of respondents (potentially influenced by<br />

the sampling frame). It is likely that respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, including<br />

interests <strong>and</strong> their primary reason <strong>for</strong> interaction with the l<strong>and</strong>scape, will have an impact on the<br />

overall results as to both l<strong>and</strong>scape preference <strong>and</strong> valuation. For example White <strong>and</strong> Lovett<br />

(1999) carried out both a postal survey <strong>and</strong> interviews with visitors to the North York Moors<br />

National Park. The main reasons given <strong>for</strong> visiting the National Park within the interview survey<br />

were walking <strong>and</strong> the views whereas within the postal survey bird watching was the main reason<br />

given (by 67%). There were also differences in the preferred l<strong>and</strong>scape. Of the interview<br />

respondents 70% preferred heather moorl<strong>and</strong> over broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> traditional grazing<br />

pasture. In contrast, 70% of postal survey respondents preferred broad leaved <strong>for</strong>est over<br />

heather moorl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> grazing l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

The authors attribute the difference in preferences between those interviewed <strong>and</strong> those<br />

returning a postal survey to the fact that the majority of interviews were conducted in a car park<br />

near a major road where people were likely to stop to admire the view of the moor. Respondents<br />

who had stopped in the car park were more likely to favour the l<strong>and</strong>scape which offered most<br />

recreational value; in contrast, <strong>for</strong> survey respondents rating broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> as the most<br />

important l<strong>and</strong>scape feature, the perceived degree of threat was the single most important factor.<br />

Similarly, Black (2009) found that over half of the respondents to a questionnaire<br />

distributed within the North Pennines National Park were members of environmental<br />

organisations. The author notes that environmental organisation members scored significantly<br />

higher than non-members in a knowledge quiz on wildlife <strong>and</strong> conservation, <strong>and</strong> were<br />

significantly more likely to pay <strong>for</strong> desired environmental outcomes. Those with higher quiz<br />

scores <strong>and</strong> environmental awareness were more likely to choose increased blanket bog or tree<br />

16

cover over the current l<strong>and</strong>scape which may explain the overall preference in the sample <strong>for</strong> an<br />

increase in blanket bog <strong>and</strong> associated increase in important birds <strong>and</strong> mammals 13 . These<br />

examples also highlight that the degree to which respondents value the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>for</strong> cultural<br />

services such as recreation is closely linked to respondents’ awareness of <strong>and</strong> views on the other<br />

services delivered by the upl<strong>and</strong>s. In the absence of the provision of additional in<strong>for</strong>mation to all<br />

respondents, the latter will depend on their respondent’s existing level of knowledge; the<br />

demographic implications of this are evident from Hanley et al.’s unsurprising finding that<br />

individuals educated to higher levels had greater environmental awareness (2007). The fact that<br />

respondents take factors such as biodiversity into account when thinking about their overall<br />

preferences <strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape also highlights the difficulty of disaggregating preferences <strong>for</strong> the<br />

cultural services from preferences <strong>for</strong> the upl<strong>and</strong>s as a whole. This reflects some of the<br />

challenges associated with the ecosystems approach highlighted in the introduction to this<br />

review.<br />

Based on a robust sample covering 5 English regions, Hanley et al (2007) found that WtP<br />

<strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> features such as moorl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes also varied spatially. Possible reasons <strong>for</strong> this<br />

heterogeneity include differences in regional cultures, in incomes, <strong>and</strong> in the relative scarcity of<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape features (as marginal WtP is expected to depend on the current abundance of a given<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape feature within a given area). In addition, the underlying reasons <strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

preferences also vary between regions. For example, income has a significant relationship with<br />

WtP <strong>for</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> features in both Yorkshire <strong>and</strong> Humber <strong>and</strong> the South East, but this relationship is<br />

positive in Yorkshire <strong>and</strong> Humber (with individuals with a higher income being more likely to want<br />

to pay <strong>for</strong> <strong>Public</strong> goods associated with the upl<strong>and</strong>s) <strong>and</strong> negative in the South East. Based on<br />

regional differences in preference, the authors raise the potential policy implication that payments<br />

to farmers should differ by region (to reflect the value of the public goods they deliver). For<br />

example, based on the findings from this study, payments <strong>for</strong> heather moorl<strong>and</strong> conservation<br />

would be highest in the West Midl<strong>and</strong>s, lowest in the North West <strong>and</strong> zero in Yorkshire <strong>and</strong><br />

Humberside. However, the authors acknowledge the obvious practical <strong>and</strong> political implication of<br />

this.<br />

Only a minority of the studies explicitly looked at the impact of in<strong>for</strong>ming the public about<br />

the link between management practices <strong>and</strong> impacts on the l<strong>and</strong>scape. Black (2009) tried to<br />

take into account the impact of giving respondents additional in<strong>for</strong>mation about the management<br />

practices (with particular reference to managing grouse moors <strong>for</strong> shooting) <strong>and</strong> found that<br />

having additional in<strong>for</strong>mation did not appear to impact on how much respondents were willing to<br />

pay <strong>for</strong> preferred l<strong>and</strong>scapes. However, it is possible that having in<strong>for</strong>mation about management<br />

practices impacted negatively on the amount that respondents were willing to pay <strong>for</strong> specific<br />

features, e.g. heather moorl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

6.3. Role of preference strength<br />

A final point that should be emphasised (<strong>and</strong> which can be addressed to an extent using<br />

economic valuation techniques) is that it is important to take into account the strength of<br />

individuals’ preferences as well as the preferences themselves. For example, although only a<br />

minority of respondents in Willis <strong>and</strong> Garrod’s sample favoured ab<strong>and</strong>oned, conserved or<br />

sporting l<strong>and</strong>scapes, those respondents who did prefer these l<strong>and</strong>scapes were, on average,<br />

willing to pay more <strong>for</strong> them than those who favoured today’s l<strong>and</strong>scape were willing to pay to<br />

maintain the status quo (1993). To an extent, strength of individuals’ preferences could be<br />

explored further by considering samples of individuals who have a more specialist engagement<br />

with the upl<strong>and</strong>s – e.g. those who use the upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>for</strong> specialist activities such as<br />

climbing or field sports. This was done by Grijalva et al. (2002) <strong>for</strong> National Parks in the United<br />

States but no comparable study <strong>for</strong> the UK was identified in the searches conducted <strong>for</strong> this<br />

literature review.<br />

13 Although it’s also likely that people favoured an increase in mammals <strong>and</strong> birds associated with an<br />

increase blanket bog because these species are likely to be more emblematic than plants <strong>and</strong> insects. A<br />

number of studies have shown that the public are more likely to pay to preserve more emblematic species.<br />

17

Summary section 6<br />

- A cautious interpretation of the evidence suggests that broadleaved woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

heather moorl<strong>and</strong> are valued features of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> that managed grassl<strong>and</strong><br />

is generally less favoured. However, when asked about the l<strong>and</strong>scape as a whole,<br />

respondents favour the maintenance of a l<strong>and</strong>scape similar to today’s or with some<br />

features such as broadleaved <strong>for</strong>est <strong>and</strong> field boundaries enhanced.<br />

- The results of studies intended to determine public preferences (<strong>and</strong> the value which the<br />

public place on the upl<strong>and</strong>s) are highly dependent on the nature of the population<br />

sampled, the nature of their engagement with the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> their existing level of<br />

knowledge.<br />

- <strong>Preferences</strong> <strong>for</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape also varied regionally <strong>and</strong> this is likely to reflect the current<br />

characteristics of different upl<strong>and</strong> areas <strong>and</strong> the socio-demographic characteristics of the<br />

population living in the region of different upl<strong>and</strong> areas.<br />

- It is important to consider the strength of individuals’ preferences as well as the<br />

preferences themselves.<br />

7. Valuation of upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

7.1. Overview of Willingness to Pay (WtP) values from reviewed studies<br />

As with table 2, all of the studies summarised in the table below specifically consider the<br />

public’s perceptions of the upl<strong>and</strong>s, however other studies which provide broader contextual<br />

findings on the UK public’s willingness to pay <strong>for</strong> cultural <strong>and</strong> other services which are linked to<br />

agriculture (see FERA et al 2010 on WtP <strong>for</strong> agri-environment schemes) are referenced as<br />

context. In terms of the economic valuation of the upl<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape there was some variation<br />

between the different studies. Willingness to Pay (WtP) values ranged from £119.05 per<br />

household/year to maintain all 11 National Parks to £3.10 to maintain just one estate within the<br />

North York Moors National Park. An overview of the WtP values derived by the various studies is<br />

given in Table 3. The majority of values are based on Contingent Valuation (CV), with the<br />